Abstract

Objective

Women with antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) are at risk for pregnancy complications associated with poor placentation and placental inflammation. While these antibodies are heterogeneous, some anti-β2GPI antibodies can activate human first trimester trophoblast TLR4 and NLRP3. The objective of this study was to determine the role of negative regulators of TLR and inflammasome function in aPL-induced trophoblast inflammation.

Methods

Human trophoblast cells were treated with or without anti-β2GPI aPL or control IgG in the presence or absence of the common TAM receptor ligand, GAS6, or the autophagy inducer, rapamycin. Expression and function of the TAM receptor pathway and autophagy was measured by qRT-PCR, Western blot and ELISA. aPL-induced trophoblast inflammation was measured by qRT-PCR, activity assays and ELISA.

Results

Anti-β2GPI aPL inhibited trophoblast TAM receptor function by reducing cellular expression of the receptors, AXL and MERTK, and the ligand GAS6. Addition of GAS6 blocked the effects of aPL on the TLR4-mediated IL-8 response. However, the NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1β response was unaffected by GAS6, suggesting another regulatory pathway was involved. Indeed, anti-β2GPI aPL inhibited basal trophoblast autophagy, and reversing this with rapamycin inhibited aPL-induced inflammasome function and IL-1β secretion.

Conclusion

Basal TAM receptor function and autophagy may serve to inhibit trophoblast TLR and inflammasome function, respectively. Impaired TAM receptor signaling and autophagy by anti-β2GPI aPL may allow subsequent TLR and inflammasome activity leading to a robust inflammatory response.

Introduction

Women with antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) are at high risk for recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) and late pregnancy complications, such as preeclampsia (1). Placental inflammation is a hallmark of adverse pregnancy outcomes like preeclampsia, including those complicated by aPL (2, 3). aPL recognizing beta2 glycoprotein I (β2GPI) preferentially bind the placental trophoblast and subsequently alter trophoblast function (4, 5). We previously demonstrated that aPL recognizing β2GPI trigger human first trimester trophoblast cells to produce elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines via activation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (6); and independently of TLR4, inhibit spontaneous trophoblast migration and modulate trophoblast angiogenic factor secretion (7, 8). Further investigation of this TLR4-mediated inflammatory response revealed that anti-β2GPI aPL elevated trophoblast endogenous uric acid, which in turn activated the NLRP3 inflammasome to induce IL-1β processing and secretion (9). In parallel, anti-β2GPI aPL via TLR4 induced trophoblast expression of the microRNA, miR-146a-3p, which in turn activated the RNA sensor, TLR8, to drive IL-8 secretion (10).

Despite some aPL being able to induce a robust TLR4 and NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory response, human first trimester trophoblast cells do not generate a classic inflammatory response to physiological doses of the natural TLR4 ligand, bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (11–14). Thus, in human first trimester trophoblast, TLR4 function and subsequent inflammasome activation may be tightly regulated, and aPL might override this braking mechanism.

One way in which TLR function can be inhibited is through activation of the TAM receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK), a novel family of negative regulators (15, 16). Three TAM receptors: TYRO3, AXL, and MERTK, are activated by two endogenous ligands: growth arrest specific 6 (GAS6) and Protein S1 (PROS1). GAS6 binds and activates all three TAM receptors, while PROS1 activates TYRO3 and MERTK (15, 16). Upon ligand binding, TAM receptors trigger STAT1 phosphorylation, inducing expression of SOCS1 and SOCS3, which inhibit TLR signaling (15, 16). While autophagy is a regulatory process that facilitates the degradation and recycling of cytoplasmic components via lysosomes (17), autophagy is also a negative regulator of inflammasome activity and subsequent IL-1β production (18, 19). Furthermore, in normal pregnancy, extravillous trophoblast cells express high levels of basal autophagy, which is necessary for their invasion and vascular remodeling (20). The objective of this study was to determine the role of negative regulators of TLR and inflammasome function in anti-β2GPI aPL-induced trophoblast inflammation by studying the TAM receptor pathway and autophagy.

Material and Methods

Reagents

Recombinant (r) GAS6 was purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN). The autophagy inducer, rapamycin, and the autophagy inhibitor, bafilomycin, were obtained from Invivogen (San Diego, CA). The ADAM17 inhibitor, TAPI-0 was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Trophoblast cell lines

The human first trimester extravillous trophoblast telomerase-transformed cell line, Sw.71 (21), was used in these studies. The human first trimester extravillous trophoblast cell line HTR8 was also used and was a kind gift from Dr Charles Graham (Queens University, Kingston, ON, Canada) (22).

Isolation of primary trophoblast from first trimester placenta

First trimester placentas (7–12 weeks gestation) were obtained from elective terminations of normal pregnancies performed at Yale-New Haven Hospital. The use of patient samples was approved by Yale University’s Human Research Protection Program. Trophoblast cell isolation was performed as previously described (10).

Antiphospholipid antibodies

Unless specified, this study used the aPL, IIC5, which is a mouse IgG1 anti-human β2GP1 monoclonal antibody (mAb). For some experiments, the aPL, ID2, which is also a mouse IgG1 anti-human β2GP1 mAb was used. These aPL has been previously characterized. Like patient-derived polyclonal aPL, IIC5 and ID2 bind β2GPI when immobilized on a negatively charged surface such as the phospholipids, cardiolipin, phosphatidyl serine or irradiated polystyrene, and thus behave as both anti-cardiolipin and anti-β2GPI antibodies (Ab) (23). IIC5 and ID2 react specifically with an epitope within domain V of β2GPI (24). Furthermore, IIC5 and ID2 both have pronounced lupus anticoagulant activity and thus both antibodies are “triple positive” aPL (25). IIC5 and ID2 are appropriate models for human aPL since they share similar epitopes; IIC5 and ID2 can block human polyclonal aPL binding to β2GPI (26). Moreover, IIC5 and ID2 bind to human first trimester extravillous trophoblast cells (6, 27, 28), and alter their function in a similar fashion to patient-derived polyclonal aPL-IgG (9), and polyclonal IgG aPL recognizing β2GPI (6, 8). In particular for this study, both the anti-human β2GP1 mAb and patient-derived aPL upregulate trophoblast secretion of inflammatory IL-8 and IL-1β (6, 9). Mouse IgG1 clone 107.3 (BD Biosciences) was used as an isotype control. Trophoblast cells were treated with aPL or the IgG isotype control at 20μg/ml as previously described (6–10).

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

Trophoblast cellular RNA was extracted using TRIzol as described (29). Expression of miR-146a-3p was measured by qRT-PCR using the Taqman MicroRNA Assay (Life Technologies) and normalized to the housekeeping gene, U6 as previously described (10). For mRNA expression of TYRO3, AXL, MERTK, GAS6, PROS1, SOCS1, SOCS3, IFNA, IFNB, and GAPDH, qRT-PCR was performed using the KAPA SYBR Fast qPCR kit (Kapa Biosystems, Woburn, MA), and PCR amplification performed on the BioRad CFX Connect Real-time System (BioRad). The primers use in this study are shown in Table 1. Data were analyzed using the Δ-Δ CT method and plotted as fold change (FC) in miR or mRNA expression normalized to the endogenous control/internal reference.

Table I.

Primers used for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Forward (5′ to 3′) | Reverse (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| TYRO3 | CGGTAGAAGGTGTGCCATTTT | CGATCTTCGTAGTTCCTCTCCAC |

| AXL | CCGTGGACCTACTCTGGCT | CCTTGGCGTTATGGGCTTC |

| MERTK | CTCTGGCGTAGAGCTATCACT | AGGCTGGGTTGGTGAAAACA |

| GAS6 | GGCAGACAATCTCTGTTGAGG | GACAGCATCCCTGTTGACCTT |

| PROS1 | TGCTGGCGTGTCTCCTCCTA | CAGTTCTTCGATGCATTCTCTTTCA |

| GAPDH | CAGCCTCCCGCTTCGCTCTC | CCAGGCGCCCAATACGACCA |

| SOCS1 | CTGGGATGCCGTGTTATTTT | TAGGAGGTGCGAGTTCAGGT |

| SOCS3 | GCAAGCTGCAGGAGAGCGGATT | AAGAAGTGGCGCTGGTCCGA |

| IFNA | GCAAGCCCAGAAGTATCTGC | ACTGGTTGCCATCAAACTCC |

| IFNB | AGCACTGGCTGGAATGAGAC | TCCTTGGCCTTCAGGTAATG |

Western Blot

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (9). HSP90 was used as internal control to validate the amount of protein loaded onto the gels. Images were recorded and semi-quantitative densitometry performed using the Gel Logic 100 and Kodak MI software (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) and normalized to signals for HSP90. The following primary antibodies to human proteins were used: TYRO3 (#MAB859, R&D Systems); AXL (#AF154, R&D Systems); MERTK (#AF891, R&D Systems); phosphorylated (p) AXL (#9271, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA); pMERTK (#ab192649, AbCam, Cambridge, MA); total (t) STAT1 (#9172, Cell Signaling); pSTAT1 (#7649, Cell Signaling); SOCS1 (#3950; Cell Signaling) ; SOCS3 (#2923, Cell Signaling); LC3BI/II (#2775, Cell Signaling); p62/SQSTM1 (#5114 ; Cell Signaling); and HSP90 (H-114; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Measurement of cytokines, uric acid, caspase-1 and TAM receptor ligands

Trophoblast culture supernatants and for some factors, lysates, were analyzed for IL-1β, VEGF, PlGF, sEndoglin, and GAS6 using ELISA kits from R&D Systems; for IL-8 using an ELISA kit from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY); and for total PROS1 using an ELISA from Innovative Research Inc. (Novi, MI). For the measurement of uric acid, supernatants were analyzed using the QuantiChrom assay kit from BioAssay Systems (Hayward, CA). Caspase-1 activity was measured using the caspase-Glo 1 inflammasome assay from Promega (Madison, WI).

Trophoblast migration

Trophoblast cell migration was measured using a two-chamber colormetric assay from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA) as previously described (7, 10).

Measurement of sAXL, sMERTK and GAS6 in Patient Samples

Plasma was collected as part of The PROMISSE Study (Predictors of pRegnancy Outcome: bioMarkers In antiphospholipid antibody Syndrome and Systemic lupus Erythematosus), a multicenter National Institutes of Health-funded prospective observational study of pregnancies of women with aPL, SLE, or both, as well as healthy pregnant controls. Details about this cohort of patients, as well as inclusion and exclusion criteria, have been previously published (9, 10, 30–33). This paper concerns a subset of pregnant participants who have aPL (aPL+) either with or without SLE (n=38), and healthy pregnant controls (n=16). We also studied SLE patients (SLE+) without aPL (aPL−) (n=29). Adverse pregnancy outcomes (APO) were defined as the occurrence of one or more of the following: 1) otherwise unexplained fetal death; 2) neonatal death prior to hospital discharge and due to complications of prematurity; 3) indicated preterm delivery prior to 37 weeks’ gestation because of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia or placental insufficiency; 4) birth weight <5th percentile and/or delivery before 37 weeks because of IUGR and confirmed by birth weight <10th percentile. The frequency of APOs for the entire cohort were previously reported (10). From the aPL+ (SLE+ or SLE−) group, 20 patients were APO+, and from the aPL− SLE+ group, 11 patients were APO+. Plasma collected during the second trimester (18–27 weeks gestation) was analyzed for sAXL, sMERTK and GAS6 by ELISA (R&D Systems).

Statistical analysis

Each treatment experiment was performed at least three times. All analyses were performed in duplicate or triplicate. All data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of pooled experiments. The number of independent experiments that data were pooled from are indicated in the figure legends as “n=“. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 and determined using Prism Software (Graphpad, Inc; La Jolla, CA). For normally distributed data, significance was determined using either one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for multiple comparisons or a t-test. For data not normally distributed, significance was determined using a non-parametric multiple comparison test for multiple comparisons or the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test.

Results

Antiphospholipid antibodies inhibit trophoblast TAM receptor and ligand expression

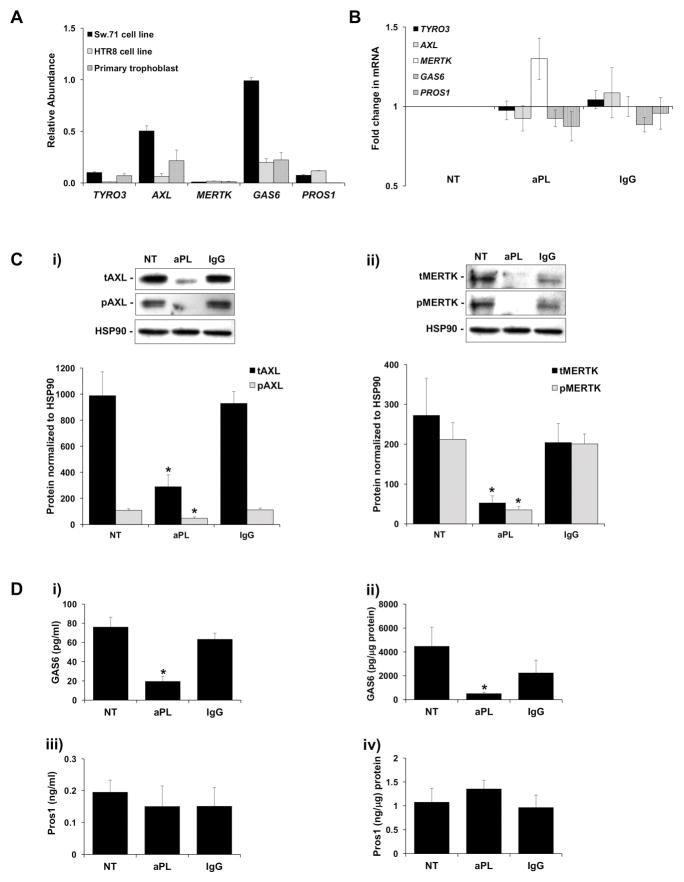

As shown in Figure 1A, at the mRNA level, first trimester trophoblast cell lines (Sw.71 and HTR8) as well as primary human first trimester trophoblast cells expressed basal levels of the TAM receptors TYRO3, AXL and MERTK; and their ligands, GAS6 and PROS1. After treatment with aPL or an IgG isotype control, trophoblast mRNA levels of TYRO3, AXL, MERTK, GAS6 or PROS1 were not significantly different from the no treatment (NT) control (Figure 1B). However, as shown in Figures 1C and 1D, aPL did change their protein expression. Under NT and IgG control conditions, trophoblast cells expressed high levels of total and phosphorylated (i) AXL and (ii) MERTK (Figure 1C). After exposure to aPL, (i) total and phosphorylated AXL was significantly reduced by 75.9±9.1% and 49.9±11.7%, respectively; and (ii) total and phosphorylated MERTK was significantly reduced by 84.1±4.7% and 76.0±6.2%, respectively, when compared to the NT control (Figure 1C). TYRO3 protein expression was undetectable under all conditions (data not shown). As shown in Figure 1D, under NT and IgG control conditions, trophoblast cells expressed high levels of secreted and cellular GAS6 and PROS1. After exposure to aPL, (i) secreted and (ii) cellular GAS6 was significantly reduced by 78.6±5.3% and 81.4±3.4%, respectively, when compared to the NT control (Figure 1D). In contrast aPL had no significant effect on either the (iii) secreted or (iv) cellular levels of PROS1 compared to the controls (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Antiphospholipid antibodies inhibit trophoblast TAM receptor and ligand expression.

(A) qRT-PCR was used to measure basal mRNA levels for TYRO3, AXL, MERTK, GAS6 and PROS1 in the Sw.71 cell line (n=6); the HTR8 cell line (n=3); and in primary first trimester trophoblast cells (n=3). (B) After a 48 hr exposure to no treatment (NT), aPL, or control IgG, Sw.71 cells were measured for TYRO3, AXL, MERTK, GAS6 and PROS1 mRNA levels (n=8). (C–D) Sw.71 cells were treated with no treatment (NT), aPL, or control IgG. After 72 hrs cell-free supernatants and cellular protein were collected. (C) Total (t) and phosphorylated (p) (i) AXL; and (ii) MERTK were measured by Western blot. HSP90 served as a loading control. Blots are from one representative experiment. Barcharts show (i) tAXL and pAXL; or (ii) tMERTK and pMERTK levels as determined by densitometry after normalization to HSP90 (n=4–6). (D) ELISA was used to measure (i) secreted GAS6; (ii) cellular GAS6; (iii) secreted PROS1; and (iv) cellular PROS1 (n=4–8). *p<0.05 relative to the NT control unless otherwise indicated.

Antiphospholipid antibodies inhibit trophoblast TAM receptor signaling

Having demonstrated reduced AXL, MERTK, and GAS6 protein expression, and reduced AXL and MERTK activation in trophoblast cells exposed to aPL, the functional impact of this was investigated by examining the downstream signaling pathway. Under NT and IgG control conditions, trophoblast cells expressed high levels of phosphorylated and total STAT1, and high levels of SOCS1 and SOCS3 (Figure 2A). After treatment with aPL, the pSTAT1/tSTAT1 ratio was significantly inhibited by 62.4±11.6% when compared to the NT control (Figure 2A & B). After treatment with aPL, protein expression of SOCS1 and SOCS3 was also significantly inhibited by 76.4±6.0% and 30.1±5.2%, respectively, when compared to the NT control (Figure 2A & C). This was reflected at the mRNA level. Treatment of trophoblast cells with aPL significantly reduced SOCS1 and SOCS3 mRNA levels by 58.9±11.3% and 30.1±8.3%, respectively when compared to the NT control (Figure 2D). Since type I IFNs can also induce SOCS1/SOCS3 through activation of the interferon-α/β receptor (IFNAR) (34), the effect of aPL on these factors were examined. As shown in Figure 2D, treatment of trophoblast cells with aPL significantly reduced IFNB mRNA levels by 78.6±7.0% when compared to the NT control, while control IgG had no significant effect. IFNA mRNA levels were unaltered under all conditions (data not shown).

Figure 2. Antiphospholipid antibodies inhibit trophoblast TAM receptor signaling.

Sw.71 cells were treated with no treatment (NT), aPL, or control IgG. After 48 hrs cellular RNA, and after 72 hrs, cellular protein, was collected. (A) Western blot was used to detect phosphorylated (p) and total (t) STAT1, as well as SOCS1 and SOCS3 levels. HSP90 served as a loading control. Blots are from one representative experiment. (B) The pSTAT1/tSTAT1 ratio (n=5); and (C) levels of SOCS1 and SOCS3 (n=3–5) were determined by densitometry of Western blots after normalization to HSP90. (D) Levels of SOCS1, SOCS3, and IFNB mRNA after normalization to GAPDH (n=7–8). *p<0.05 relative to the NT control.

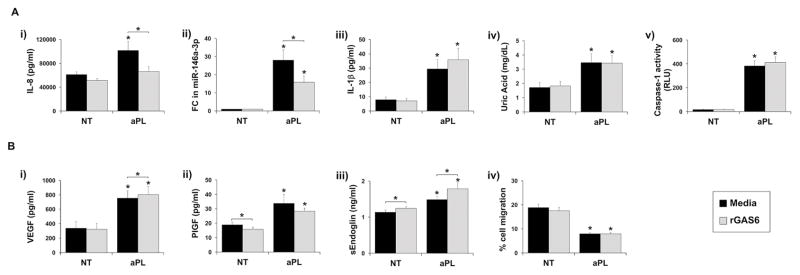

GAS6 reverses antiphospholipid antibody-induced miR-146a-3p expression and IL-8 secretion, but not uric acid or IL-1β production

To determine if the attenuation of the TAM receptor signaling pathway by aPL played a role in regulating the trophoblast TLR4-mediated inflammatory response (6, 9, 10), recombinant (r) GAS6 was introduced into the culture. As shown in Figure 3A the TLR4-mediated aPL-induced (i) IL-8 secretion and (ii) miR-146a-3p expression were both inhibited by the presence of rGAS6. rGAS6 significantly inhibited aPL-induced (i) IL-8 secretion by 29.7±9.8%, and (ii) miR-146a-3p expression by 37.8±9.0%. In contrast the TLR4-mediated induction of (iii) IL-1β secretion; (iv) uric acid production; and (v) caspase-1 activation by aPL were not altered by rGAS6 (Figure 3A). As shown in Figure 3B the aPL-mediated TLR4-independent regulation of trophoblast (i) VEGF; (ii) PlGF; (iii) sEndoglin, and (iv) cell migration (7, 8) were not reversed by the presence of rGAS6. However, there were some minimal, yet statistically significant, effects of rGAS6 on trophoblast angiogenic factor production. As shown in Figure 3B, rGAS6 significantly: (i) increased aPL-induced VEGF by 1.1±0.1 fold; (ii) reduced basal PlGF by 16.8±10.1%; and (iii) increased basal and aPL-induced sEndoglin by 1.1±0.1 and 1.2±0.1 fold, respectively.

Figure 3. rGAS6 reverses antiphospholipid antibody-induced miR-146a-3p expression and IL-8 secretion.

Sw.71 or HTR8 cells were treated with no treatment (NT) or aPL in the presence of media or rGAS6 (100ng/ml). After 48 hrs cellular RNA was collected or cell migration was measured (n=5). After 72 hrs cell-free supernatants were collected (n=5). (A) TLR4-mediated: (i) IL-8 secretion; (ii) fold change (FC) in miR-146a-3p expression; (iii) IL-1β secretion; (iv) uric acid secretion; and (v) caspase-1 activity was measured. (B) TLR4-independent: (i) VEGF secretion; (ii) PlGF; secretion; (iii) sEndoglin secretion; and (iv) cell migration were measured. *p<0.05 relative to the NT control under each condition (media or rGAS6) unless otherwise indicated.

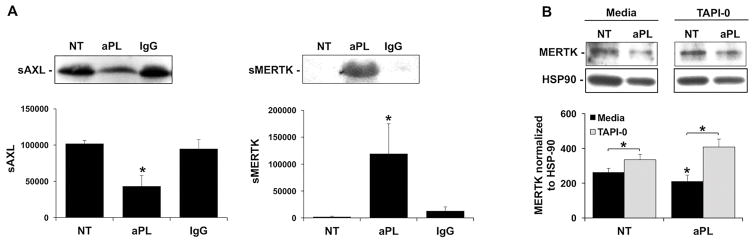

Antiphospholipid antibodies promote trophoblast sMERTK release through ADAM17

The mechanism by which aPL inhibits the TAM receptor signaling pathway, allowing for subsequent TLR4-mediated miR-146a-3p expression and IL-8 secretion, was next investigated. The ectodomain of MERTK is proteolytically cleaved by the metalloproteinase, ADAM17, to generate soluble (s) MERTK (35, 36), while sAXL is released through activation of ADAM10 (37). To investigate whether treatment of aPL promoted the release of sAXL and sMERTK, which may account for the reduced cellular expression, trophoblast were treated with or without aPL, and the cell-free culture supernatants evaluated for the soluble receptors. As shown in Figure 4A, under no treatment and IgG control conditions, sMERTK was undetectable by Western blot. However, after exposure to aPL there was a significant 32.8±3.1-fold increase in sMERTK expression. Surprisingly, under no treatment and IgG control conditions, there was a high amount of detectable sAXL, and treatment with aPL significantly reduced this by 57.7±13.9% (Figure 4A). To examine the mechanism by which aPL promoted trophoblast sMERTK release, trophoblast cells were treated with aPL in the presence and absence of an ADAM17 inhibitor. As shown in Figure 4B, treatment of trophoblast cells with the ADAM17 inhibitor, TAPI-0, completely and significantly reversed the ability of aPL to reduce cellular MERTK expression.

Figure 4. aPL promote trophoblast sMERTK release through ADAM17.

(A) Sw.71 cells were treated with no treatment (NT), aPL or control IgG for 72hr after which cell-free supernatants were analyzed for sAXL and sMERTK by Western blot. Blots are from one representative experiment. Barcharts show sAXL or sMERTK levels as determined by densitometry (n=4) *p<0.05 relative to the NT control. (B) Sw.71 cells were treated with no treatment (NT) or aPL in the presence of media or the ADAM17 inhibitor, TAPI-0 (2.5μM). After 72hrs cell lysates were collected. MERTK expression was measured by Western blot. HSP90 served as a loading control. Blots are from one representative experiment. Barchart shows MERTK levels as determined by densitometry after normalization to HSP90 (n=4) *p<0.05 relative to the NT control under each condition (media or TAPI-0) unless otherwise indicated.

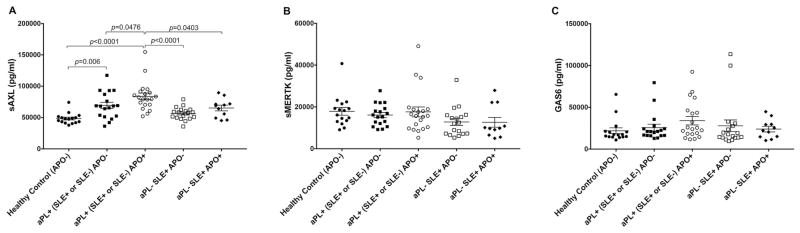

Pregnant women with aPL and adverse pregnancy outcomes (APO) have elevated circulating sAXL

We next sought to determine whether our in vitro findings, which model what occurs in the placental trophoblast at the maternal-fetal interface, were detectable at the systemic level. We analyzed the plasma collected at 18–27 weeks gestation from pregnant women with aPL (aPL+) (with or without SLE) for sAXL, sMERTK and GAS6 levels, and compared them to women with or without an adverse pregnancy outcome (APO). As shown in Figure 5A, plasma sAXL levels in patients who had aPL (with or without SLE) either with an APO [aPL+ (SLE+ or SLE−) APO+] or without an APO [aPL+ (SLE+ or SLE−) APO−] were significantly higher compared to plasma from healthy controls. Moreover, patients with aPL and an APO had significantly higher sAXL levels when compared to patients with aPL and without an APO (Figure 5A). To determine whether APOs in autoimmune patients without detectable aPL have aberrant expression of sAXL, we analyzed plasma from aPL negative (aPL−) SLE (SLE+) patients with and without APOs. Plasma sAXL levels in patients without aPL but with SLE, either with an APO [aPL− SLE+ APO+] or without an APO [aPL− SLE+ APO−], were not significantly different from the healthy controls, and were significantly lower than the aPL+ patients with an APO (Figure 5A). There were no significant differences in the plasma levels of sMERTK (Figure 5B) or GAS6 (Figure 5C) between any of the patient groups or controls.

Figure 5. Circulating sAXL levels are elevated in pregnant women with aPL and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Plasma was measured for the levels of sAXL, sMERTK and GAS6 from the following patients: Healthy control adverse pregnancy outcome negative (APO−) (n=16); antiphospholipid antibody positive (aPL+) (SLE+ or SLE−) APO− (n=18); aPL+ (SLE+ or SLE−) APO+ (n=20); aPL− SLE+ APO− (n=19); and aPL− SLE+ APO+ (n=11). Charts show levels of (A) sAXL; (B) sMERTK; and (C) GAS6 for each patient plotted.

Antiphospholipid antibodies inhibit trophoblast autophagy leading to inflammasome activation

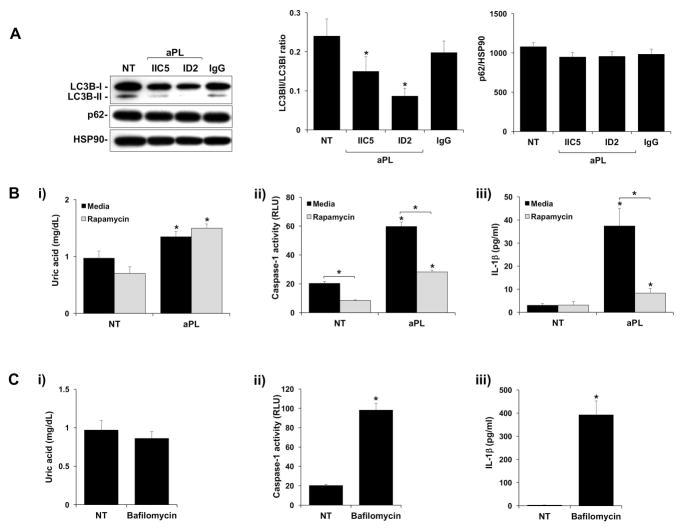

Despite inhibiting TAM receptor function, rGAS6 was unable to reverse the effects of aPL on TLR4-mediated uric acid production; caspase-1 activation; and subsequent IL-1β secretion (9). Therefore, we sought to examine other regulatory pathways that might be involved in the modulation of this aPL inflammasome-mediated response (9). Since autophagy is a negative regulator of inflammasome activity (18, 19); and is active under normal conditions in extravillous trophoblast cells (20), we investigated this process. As shown in Figure 6A, under NT and IgG control conditions, trophoblast cells expressed high levels of the autophagy marker LC3BI and LC3BII, and sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1/p62), a specific autophagy substrate (38). After treatment with two different aPL (IIC5 and ID2), the trophoblast LC3BII/LC3BI ratio was significantly reduced by 43.3±20.1% and 60.3±16.1%, while levels of p62 were unchanged under all treatment conditions (Figure 6A). p62 levels are known to stabilize or accumulate when LC3BII/LC3BI-associated autophagy is impaired in the trophoblast and other model systems (20) (38, 39). To determine whether the observed reduction in autophagy might allow for aPL-mediated inflammasome function, trophoblast cells were treated with aPL in the presence of the autophagy inducer, rapamycin. As shown in Figure 6B(i), while the aPL induction of uric acid was not affected by the presence of rapamycin, aPL-induced (ii) caspase-1 activity and (iii) IL-1β secretion were significantly inhibited by (i) 52.0±2.6% and (ii) 77.1±3.6% (Figure 6B). In the absence of aPL, treatment of trophoblast cells with the autophagy inhibitor, bafilomycin had no effect on uric acid production (Figure 6C; i). However, when compared to the NT control, bafilomycin significantly increased trophoblast (ii) caspase-1 activity by 4.8±0.2 fold; and (iii) IL-1βsecretion by 181.9±50.8 fold (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Antiphospholipid antibodies inhibit trophoblast autophagy leading to inflammasome activation.

(A) Sw.71 cells were treated with no treatment (NT), aPL or control IgG. After 8hrs cellular protein was collected. Western blot was used to detect LC3BI, LC3BII and p62. HSP90 served as a loading control. Blots are from one representative experiment. The LC3BII/LC3BI ratio and levels of p62, was determined by densitometry after normalization to HSP90 (n=4). (B) Sw.71 cells were treated with no treatment (NT) or aPL in the presence of media or rapamycin (500nM). After 72hrs supernatants were measured for (i) uric acid; (ii) caspase-1 activity, or (iii) IL-1β (n=6–7). (C) Sw.71 cells were treated with no treatment (NT) or bafilomycin (0.5μM). After 72hrs supernatants were measured for (i) uric acid; (ii) caspase-1 activity, or (iii) IL-1β (n=6–7). *p<0.05 relative to the NT control under each condition unless otherwise indicated.

Discussion

Placental inflammation is a hallmark of pregnancy complications, such as preeclampsia and preterm birth (40), but in many cases the trigger and mechanisms involved are unknown. In obstetric APS, it is well established that pathogenic aPL recognizing β2GPI target the placenta, causing pathology that results in pregnancy loss and late gestational complications (5). While pregnancies complicated by aPL have evidence of inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface (2, 3), our understanding of the mechanisms involved are incomplete. In the current study, we report for the first time that aPL override negative regulators of placental trophoblast TLR and inflammasome signaling to induce a robust inflammatory response.

Through the expression of a wide range of innate immune TLRs, Nod-like receptors (NLR) and inflammasome family members, the trophoblast can generate diverse inflammatory, specialized, and regulatory responses to infectious stimuli (11, 41). These pathways can also be activated by non-infectious triggers (42–44), including aPL (6, 9, 10). Specifically, aPL recognizing β2GPI, upon binding to human first trimester extravillous trophoblast, activate the TLR4 pathway to induce endogenous secondary signals that in turn activate other innate immune pathways within the cell (6). TLR4-mediated uric acid in response to anti-β2GPI Abs activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, promoting an IL-1β response (9). At the same time, TLR4-mediated expression of miR-146a-3p leads to activation of TLR8, promoting an IL-8 response (10). Recent studies in endothelial cells have also demonstrated that aPL activation of TLR4 can lead to the induction of secondary mediators of pathology (45). It is important to note that both human polyclonal aPL and the well characterized anti-β2GPI mAbs used in this current study induce similar trophoblast inflammatory responses; specifically elevated IL-8 and uric acid-mediated IL-1β processing and secretion (6, 9). However, aPL are highly heterogeneous, and thus our findings may not apply to all aPL.

Despite being able to sense and respond to a number of different TLR and NLR ligands (41, 46), physiological doses of the natural TLR4 agonist, LPS, are not sufficient to induce human first trimester trophoblast to generate a classic inflammatory cytokine response (11–14). A recent study showed that the type I interferon, IFNβ, serves as a key immunomodulator of LPS-driven TLR4 activation in the trophoblast (14), indicating that in these cells, TLR4 signaling is indeed tightly regulated. Thus, in contrast to cells of the immune system, the trophoblast innate immune properties may be constitutively limited by negative regulatory mechanisms (16). This current study sought to investigate how aPL recognizing β2GPI, which can directly interact with TLR4 (45, 47, 48) and activate the TLR4 pathway (6, 9), might overcome such braking mechanisms.

Herein, we report that under basal conditions, human first trimester constitutively express high levels of the TAM receptors, AXL and MERTK, and the TAM receptor ligands, GAS6 and PROS1, indicating that TLR function in these cells is constitutively suppressed (16). Indeed, the TAM receptor signaling pathway is highly active in these cells under resting conditions, evidenced by AXL, MERTK and STAT1 phosphorylation, and high expression of SOCS1 and SOCS3. Although AXL has a greater affinity for GAS6 than MERTK (49), unlike AXL, MERTK can bind both GAS6 and PROS1 (16). Thus, since trophoblast cells produce both ligands, MERTK might be the dominant functional TAM receptor in resting human first trimester trophoblast cells. After exposure to anti-β2GPI aPL, trophoblast expression of total and phosphorylated AXL and MERTK, as well as GAS6 was inhibited resulting in the inactivation of the TAM receptor signaling pathway. This allowed for the TLR4-mediated miR-146a-3p-TLR8 arm of the aPL-driven inflammatory pathway (10) to occur, since this could be blocked by rGAS6. In addition to acting as a TAM receptor ligand, GAS6 can modulate AXL and MERTK expression (50, 51). Thus, the addition of rGAS6 may serve as both an agonist and receptor modulator in order to re-establish TAM receptor function. As expected, the TLR4-independent effects of aPL on trophoblast function were not reversed by rGAS6.

One way in which TAM receptor expression and activation can be regulated is through the generation of proteolytically cleaved soluble proteins. sAXL and sMERTK are released through the activation of the metalloproteinases ADAM10 and ADAM17 (TACE), respectively (35–37). In our current study, we show that under basal conditions trophoblast cells constitutively released sAXL, but not sMERTK. This further supports the notion that MERTK might be the dominant functional TAM receptor in human first trimester trophoblast under basal conditions. Treatment of trophoblast cells with aPL induced the release of sMERTK, while sAXL release was reduced. Furthermore, under aPL conditions, ADAM17 inhibition reversed the reduced cellular expression of MERTK. This suggests that aPL promotes the release of sMERTK from the trophoblast cell surface, and this may account for the reduced cellular expression. Indeed, in other cell types, LPS can promote sMERTK release, resulting in reduced cellular expression (35, 36). In contrast, the aPL inhibition of cellular AXL expression may account for reduced sAXL release. How aPL are able to inhibit AXL protein expression in the trophoblast remains unclear, but this may involve AXL protein degradation. sAXL and sMERTK act as decoy receptors for GAS6 to further prevent cell surface receptor activation. Thus, under aPL conditions, binding of GAS6 by remaining sAXL and the elevated sMERTK may also sequester it from detection, and may be responsible, in part, for the aPL-mediated reduction in trophoblast GAS6.

Having found that aPL differentially regulated trophoblast release of sAXL and sMERTK, we sought to determine whether this might also be seen clinically at the systemic level. For this, sAXL, sMERTK, and GAS6 levels were measured in the plasma from aPL− and aPL+ patients enrolled in the PROMISSE study (9, 10, 30–33). sMERTK and GAS6 plasma levels were not different between the patient groups and controls. However, pregnant women with aPL (with or without SLE) had higher circulating sAXL levels compared to the controls. Moreover, aPL+ women with an APO had higher circulating sAXL levels compared to aPL+ women without an APO. This was specific for aPL-positivity since sAXL levels in the aPL-SLE+ groups were not different from those of healthy controls. While these findings did not reflect our in vitro findings, and thus what might occur locally at the maternal-fetal interface, this clinical data suggest that plasma sAXL levels measured during the second trimester (18–27 weeks gestation) might correlate with pregnancy outcome, although more investigation is warranted. Prior to this study, circulating sAXL, sMERTK, and GAS6 levels had been studied in non-pregnant SLE patients. sAXL and sMERTK levels have been reported as being higher in SLE patients (52–54); while data for GAS6 levels vary (53, 55). One study also reported that in SLE patients, elevated sAXL and sMERTK levels correlated with aPL positivity (56). However, our findings constitute the first report of sAXL, sMERTK and GAS6 levels in pregnant women with aPL and/or SLE.

Another potential contributor to the disabled TAM receptor pathway in the trophoblast was the observed alterations in IFNβ, since type I IFNs through IFNAR, either alone or in cooperation with TAM receptors, can induce SOCS1/SOCS3 (34). Thus, the inhibition of trophoblast IFNβ expression by the anti-β2GPI Ab might contribute to the inactivation of the TAM receptor signaling pathway. The ability of aPL to render IFNβ signaling inactive is similar to findings in which trophoblast cells were infected with a virus (14).

While restoration of TAM receptor signaling by rGAS6 prevented aPL-mediated IL-8 in the trophoblast, the TLR4-mediated uric acid, and subsequent NLRP3 inflammasome mediated IL-1β response (9) was unaffected. This suggested additional inhibitory pathways may be involved in regulating the aPL-induced trophoblast inflammatory response. Autophagy is a regulatory process that facilitates the degradation and recycling of cytoplasmic components via lysosomes (17). While autophagy is important for cellular homeostasis and cell survival in response to a number of stresses (57), it can also act as a negative regulator of inflammasome activity and subsequent IL-1β production (18, 19). In normal pregnancy, basal autophagy is essential for extravillous trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling (20). Moreover, in preeclampsia extravillous trophoblast autophagy is impaired, evidenced by reduced LC3B and the stabilization or accumulation of p62 (20), as has been observed in other systems (38, 39). In keeping with this observation, we found high expression of the autophagy marker, LC3BII, under resting conditions, but in the presence of aPL, LC3BII expression was inhibited and p62 levels were stabilized, indicating that autophagy was impaired. Furthermore, inhibition of autophagy by bafilomycin induced a similar response to aPL; while maintenance of autophagy by rapamycin prevented aPL-induced inflammasome activity and subsequent IL-1β secretion. Mechanisms by which autophagy may prevent inflammasome activation include inhibiting ROS production (58), promoting inflammasome degradation (18), or by sequestering pro-IL-1β and targeting it for lysosomal degradation (58). This later mechanism is unlikely since pro-IL-1β is highly expressed in the untreated trophoblast (9). How the TLR4-mediated uric acid response is regulated remains unclear since it is neither modulated by the TAM receptor pathway nor autophagy.

In summary, our data have shown that human extravillous trophoblast TLR and inflammasome function are tightly regulated by immunomodulatory pathways - TAM receptor activity and autophagy. Disabling of the TAM receptor signaling pathway by an anti-β2GPI Ab results in TLR4 activation leading to subsequent TLR8-mediated IL-8 release. Impaired autophagy by this anti-β2GPI aPL allows inflammasome activity leading to IL-1β production. These advancements of our understanding of the mechanisms by which anti-β2GPI aPL might mediate placental inflammation may further the potential for new predictive markers and therapeutic targets for preventing obstetric APS.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants (to VMA) from the March of Dimes Foundation (Gene Discovery and Translational Research Grant #6-FY12-255), the American Heart Association (#15GRNT24480140) and the Lupus Research Institute (Novel Research grant). SMG was supported by a Yale University School of Medicine Medical Student Fellowship. ICW was supported by an International Scholarship from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). JES was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (AR49772).

The authors thank Dr Nancy Stanwood and Dr Aileen Gariepy for their help with collecting patient tissues.

Footnotes

The authors have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.D’Cruz DP, Khamashta MA, Hughes GR. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 2007;369(9561):587–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salmon JE, Girardi G, Lockshin MD. The antiphospholipid syndrome as a disorder initiated by inflammation: implications for the therapy of pregnant patients. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3(3):140–7. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0432. quiz 1 p following 87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viall CA, Chamley LW. Histopathology in the placentae of women with antiphospholipid antibodies: A systematic review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(5):446–71. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong M, Viall CA, Chamley LW. Antiphospholipid antibodies and the placenta: a systematic review of their in vitro effects and modulation by treatment. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(1):97–118. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pantham P, Abrahams VM, Chamley LW. The role of anti-phospholipid antibodies in autoimmune reproductive failure. Reproduction. 2016;151(5):R79–90. doi: 10.1530/REP-15-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulla MJ, Brosens JJ, Chamley LW, Giles I, Pericleous C, Rahman A, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies induce a pro-inflammatory response in first trimester trophoblast via the TLR4/MyD88 pathway. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2009;62(2):96–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulla MJ, Myrtolli K, Brosens JJ, Chamley LW, Kwak-Kim JY, Paidas MJ, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies limit trophoblast migration by reducing IL-6 production and STAT3 activity. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63(5):339–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll TY, Mulla MJ, Han CS, Brosens JJ, Chamley LW, Giles I, et al. Modulation of trophoblast angiogenic factor secretion by antiphospholipid antibodies is not reversed by heparin. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66(4):286–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulla MJ, Salmon JE, Chamley LW, Brosens JJ, Boeras CM, Kavathas PB, et al. A Role for Uric Acid and the Nalp3 Inflammasome in Antiphospholipid Antibody-Induced IL-1beta Production by Human First Trimester Trophoblast. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gysler SM, Mulla MJ, Guerra M, Brosens JJ, Salmon JE, Chamley LW, et al. Antiphospholipid antibody-induced miR-146a-3p drives trophoblast interleukin-8 secretion through activation of Toll-like receptor 8. Mol Hum Reprod. 2016;22(7):465–74. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaw027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrahams VM, Visintin I, Aldo PB, Guller S, Romero R, Mor G. A role for TLRs in the regulation of immune cell migration by first trimester trophoblast cells. J Immunol. 2005;175(12):8096–104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrahams VM, Bole-Aldo P, Kim YM, Straszewski-Chavez SL, Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, et al. Divergent trophoblast responses to bacterial products mediated by TLRs. J Immunol. 2004;173(7):4286–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardenas I, Mor G, Aldo P, Lang SM, Stabach P, Sharp A, et al. Placental viral infection sensitizes to endotoxin-induced pre-term labor: a double hit hypothesis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65(2):110–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Racicot K, Kwon JY, Aldo P, Abrahams V, El-Guindy A, Romero R, et al. Type I Interferon Regulates the Placental Inflammatory Response to Bacteria and is Targeted by Virus: Mechanism of Polymicrobial Infection-Induced Preterm Birth. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;75(4):451–60. doi: 10.1111/aji.12501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemke G, Rothlin CV. Immunobiology of the TAM receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(5):327–36. doi: 10.1038/nri2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothlin CV, Carrera-Silva EA, Bosurgi L, Ghosh S. TAM receptor signaling in immune homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:355–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klionsky DJ, Emr SD. Autophagy as a regulated pathway of cellular degradation. Science. 2000;290(5497):1717–21. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuk JM, Jo EK. Crosstalk between autophagy and inflammasomes. Mol Cells. 2013;36(5):393–9. doi: 10.1007/s10059-013-0298-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latz E, Xiao TS, Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(6):397–411. doi: 10.1038/nri3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakashima A, Yamanaka-Tatematsu M, Fujita N, Koizumi K, Shima T, Yoshida T, et al. Impaired autophagy by soluble endoglin, under physiological hypoxia in early pregnant period, is involved in poor placentation in preeclampsia. Autophagy. 2013;9(3):303–16. doi: 10.4161/auto.22927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Straszewski-Chavez SL, Abrahams VM, Alvero AB, Aldo PB, Ma Y, Guller S, et al. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Telomerase Immortalized First Trimester Trophoblast Cell Line, Swan 71. Placenta. 2009;30:939–48. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham CH, Hawley TS, Hawley RG, MacDougall JR, Kerbel RS, Khoo N, et al. Establishment and characterization of first trimester human trophoblast cells with extended lifespan. Exp Cell Res. 1993;206(2):204–11. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chamley LW, Konarkowska B, Duncalf AM, Mitchell MD, Johnson PM. Is interleukin-3 important in antiphospholipid antibody-mediated pregnancy failure? Fertil Steril. 2001;76(4):700–6. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01984-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albert CR, Schlesinger WJ, Viall CA, Mulla MJ, Brosens JJ, Chamley LW, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine on antiphospholipid antibody-induced changes in first trimester trophoblast function. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71(2):154–64. doi: 10.1111/aji.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viall CA, Chen Q, Stone PR, Chamley LW. Human extravillous trophoblasts bind but do not internalize antiphospholipid antibodies. Placenta. 2016;42:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viall CA, Chen Q, Liu B, Hickey A, Snowise S, Salmon JE, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies internalised by human syncytiotrophoblast cause aberrant cell death and the release of necrotic trophoblast debris. J Autoimmun. 2013;47:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chamley LW, Allen JL, Johnson PM. Synthesis of beta2 glycoprotein 1 by the human placenta. Placenta. 1997;18(5–6):403–10. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(97)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quenby S, Mountfield S, Cartwright JE, Whitley GS, Chamley L, Vince G. Antiphospholipid antibodies prevent extravillous trophoblast differentiation. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(3):691–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.07.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potter JA, Garg M, Girard S, Abrahams VM. Viral single stranded RNA induces a trophoblast pro-inflammatory and antiviral response in a TLR8-dependent and -independent manner. Biol Reprod. 2015;92(1):17. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.124032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lockshin MD, Kim M, Laskin CA, Guerra M, Branch DW, Merrill J, et al. Prediction of adverse pregnancy outcome by the presence of lupus anticoagulant, but not anticardiolipin antibody, in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(7):2311–8. doi: 10.1002/art.34402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salmon JE, Heuser C, Triebwasser M, Liszewski MK, Kavanagh D, Roumenina L, et al. Mutations in complement regulatory proteins predispose to preeclampsia: a genetic analysis of the PROMISSE cohort. PLoS Med. 2011;8(3):e1001013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buyon JP, Kim MY, Guerra MM, Laskin CA, Petri M, Lockshin MD, et al. Predictors of Pregnancy Outcomes in Patients With Lupus: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.7326/M14-2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrade D, Kim M, Blanco LP, Karumanchi SA, Koo GC, Redecha P, et al. Interferon-alpha and angiogenic dysregulation in pregnant lupus patients who develop preeclampsia. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(4):977–87. doi: 10.1002/art.39029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothlin CV, Ghosh S, Zuniga EI, Oldstone MB, Lemke G. TAM receptors are pleiotropic inhibitors of the innate immune response. Cell. 2007;131(6):1124–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sather S, Kenyon KD, Lefkowitz JB, Liang X, Varnum BC, Henson PM, et al. A soluble form of the Mer receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits macrophage clearance of apoptotic cells and platelet aggregation. Blood. 2007;109(3):1026–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thorp E, Vaisar T, Subramanian M, Mautner L, Blobel C, Tabas I. Shedding of the Mer tyrosine kinase receptor is mediated by ADAM17 protein through a pathway involving reactive oxygen species, protein kinase Cdelta, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) J Biol Chem. 2011;286(38):33335–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.263020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinger JG, Omari KM, Marsden K, Raine CS, Shafit-Zagardo B. Up-regulation of soluble Axl and Mer receptor tyrosine kinases negatively correlates with Gas6 in established multiple sclerosis lesions. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(1):283–93. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka S, Hikita H, Tatsumi T, Sakamori R, Nozaki Y, Sakane S, et al. Rubicon inhibits autophagy and accelerates hepatocyte apoptosis and lipid accumulation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 2016;64(6):1994–2014. doi: 10.1002/hep.28820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu YT, Tan HL, Shui G, Bauvy C, Huang Q, Wenk MR, et al. Dual role of 3-methyladenine in modulation of autophagy via different temporal patterns of inhibition on class I and III phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(14):10850–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.080796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim CJ, Romero R, Chaemsaithong P, Kim JS. Chronic inflammation of the placenta: definition, classification, pathogenesis, and clinical significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4 Suppl):S53–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abrahams VM. The role of the Nod-like receptor family in trophoblast innate immune responses. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;88(2):112–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han CS, Herrin MA, Pitruzzello MC, Mulla MJ, Werner EF, Pettker CM, et al. Glucose and Metformin Modulate Human First Trimester Trophoblast Function: a Model and Potential Therapy for Diabetes-Associated Uteroplacental Insufficiency. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73(4):362–71. doi: 10.1111/aji.12339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mulla MJ, Myrtolli K, Potter J, Boeras C, Kavathas PB, Sfakianaki AK, et al. Uric acid induces trophoblast IL-1beta production via the inflammasome: implications for the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65(6):542–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shirasuna K, Seno K, Ohtsu A, Shiratsuki S, Ohkuchi A, Suzuki H, et al. AGEs and HMGB1 Increase Inflammatory Cytokine Production from Human Placental Cells, Resulting in an Enhancement of Monocyte Migration. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;75(5):557–68. doi: 10.1111/aji.12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laplante P, Fuentes R, Salem D, Subang R, Gillis MA, Hachem A, et al. Antiphospholipid antibody-mediated effects in an arterial model of thrombosis are dependent on Toll-like receptor 4. Lupus. 2016;25(2):162–76. doi: 10.1177/0961203315603146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abrahams VM. Pattern recognition at the maternal-fetal interface. Immunol Invest. 2008;37(5):427–47. doi: 10.1080/08820130802191599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sorice M, Longo A, Capozzi A, Garofalo T, Misasi R, Alessandri C, et al. Anti-beta2-glycoprotein I antibodies induce monocyte release of tumor necrosis factor alpha and tissue factor by signal transduction pathways involving lipid rafts. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(8):2687–97. doi: 10.1002/art.22802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raschi E, Chighizola CB, Grossi C, Ronda N, Gatti R, Meroni PL, et al. beta2-glycoprotein I, lipopolysaccharide and endothelial TLR4: three players in the two hit theory for anti-phospholipid-mediated thrombosis. J Autoimmun. 2014;55:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoumacher M, Burbridge M. Key Roles of AXL and MER Receptor Tyrosine Kinases in Resistance to Multiple Anticancer Therapies. Curr Oncol Rep. 2017;19(3):19. doi: 10.1007/s11912-017-0579-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun B, Qi N, Shang T, Wu H, Deng T, Han D. Sertoli cell-initiated testicular innate immune response through toll-like receptor-3 activation is negatively regulated by Tyro3, Axl, and mer receptors. Endocrinology. 2010;151(6):2886–97. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cross SN, Potter JA, Aldo P, Kwon JY, Pitruzzello M, Tong M, et al. Viral Infection Sensitizes Human Fetal Membranes to Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide by MERTK Inhibition and Inflammasome Activation. J Immunol. 2017;199(8):2885–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ekman C, Jonsen A, Sturfelt G, Bengtsson AA, Dahlback B. Plasma concentrations of Gas6 and sAxl correlate with disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(6):1064–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu H, Sun X, Zhu L, Hu F, Shi L, Fan C, et al. Different expression patterns and clinical significance of mAxl and sAxl in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2014;23(7):624–34. doi: 10.1177/0961203314520839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu J, Ekman C, Jonsen A, Sturfelt G, Bengtsson AA, Gottsater A, et al. Increased plasma levels of the soluble Mer tyrosine kinase receptor in systemic lupus erythematosus relate to disease activity and nephritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(2):R62. doi: 10.1186/ar3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim HA, Nam JY, Jeon JY, An JM, Jung JY, Bae CB, et al. Serum growth arrest-specific protein 6 levels are a reliable biomarker of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(1):143–50. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zizzo G, Guerrieri J, Dittman LM, Merrill JT, Cohen PL. Circulating levels of soluble MER in lupus reflect M2c activation of monocytes/macrophages, autoantibody specificities and disease activity. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(6):R212. doi: 10.1186/ar4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saito S, Nakashima A. Review: The role of autophagy in extravillous trophoblast function under hypoxia. Placenta. 2013;34(Suppl):S79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen S, Sun B. Negative regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome signaling. Protein Cell. 2013;4(4):251–8. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-2128-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]