Abstract

Background

A 27-year-old female was seen for long QT syndrome. She was found to be a carrier of two variants, KCNQ1 Val162Met and KCNH2 Ser55Leu, and both were annotated as pathogenic by a diagnostic laboratory in part because of sequence proximity to other known pathogenic variants.

Objective

To assess the relationship between both the KCNQ1 and KCNH2 variants and clinical significance using protein structure, in vitro functional assays, and familial segregation.

Methods

We used co-segregation analysis of family, patch clamp in vitro electrophysiology, and structural analysis using recently released cryo-electron microscopy (EM) structures of both channels.

Results

The structural analysis indicates that KCNQ1 Val162Met is oriented away from functionally important regions, while Ser55Leu is positioned at domains critical for KCNH2 fast inactivation. Clinical phenotyping and electrophysiologic study further support the conclusion that KCNH2 Ser55Leu is correctly classified as pathogenic but KCNQ1 Val162Met is benign.

Conclusion

Proximity in sequence space does not always translate accurately to proximity in three-dimensional space. Emerging structural methods will add value to pathogenicity prediction.

Keywords: Long QT, KCNQ1, KCNH2, protein structure, inherited arrhythmias, rare genetic variants

Introduction

Genetic testing has become increasingly ubiquitous for management of families with genetic arrhythmia syndromes.1 Major lessons from this expanded use of clinical genetic testing are that 1) determining whether a genetic variant is disease-causing or benign is often difficult, and 2) the determination of pathogenicity may be critically important for clinical management decisions. Here, we report a family with Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) and rare variants in both KCNH2 and KCNQ1. Both mutations were classified by a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA)-approved commercial genetic testing laboratory as pathogenic. We present data from segregation analysis, functional characterization, and structural modeling to provide evidence that one variant (KCNQ1 Val162Met) is benign, and the other (KCNH2 Ser55Leu) is the disease causing mutation. Our results urge caution when interpreting the sequence-based context of variants to assign pathogenicity..

Methods

Assessment of KCNH2 Ser55Leu and KCNQ1 Val162Met structural and sequence context

We used the recently released cryo-EM structure of the human potassium KCNH2 (hERG) channel (PDBID 5VA2) to assess the spatial relationship between previously reported pathogenic variants and the variant found in the proband;2 and for KCNQ1 Val162Met, we used a newly released cryo-EM structure of Xenopus Kv7.1 (PDBID 5VMS).3 With the three-dimensional coordinates provided by these structures, we were able to visualize the overall shape and construction of the channel molecules using the PyMOL molecular graphics suite.4 We could then map onto these structures the variants implicated in the pathogenicity classification to visualize which parts of the protein might be affected by these substitutions.

Functional characterization of KCNH2 Ser55Leu and KCNQ1 Val162Met

To determine the functional consequences of KCNH2 Ser55Leu (S55L) and KCNQ1 Val162Met (V162M) we used heterologous expression in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Point mutations were introduced into KCNH2 and KCNQ1 using the QuikChange Lightning kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). All recombinant cDNA genes were sequenced to confirm the incorporation of variants. Recombinant wildtype (WT) and variant KCNH2 and KCNQ1 cDNA in pSI vectors were transiently transfected into CHO cells along with green fluorescent protein (GFP) using the FuGENE transfection system. WT and Val162Met KCNQ1 cDNA in a pSI vector were transiently transfected into CHO cells with KCNE1 and GFP to generate Iks. Cells were incubated at 37 C for 48 hours in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 5% CO2. Cells fluorescing green were selected for further electrophysiological studies. Ion currents in this study were recorded using the standard protocols as previous described.5

The study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Internal Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Results

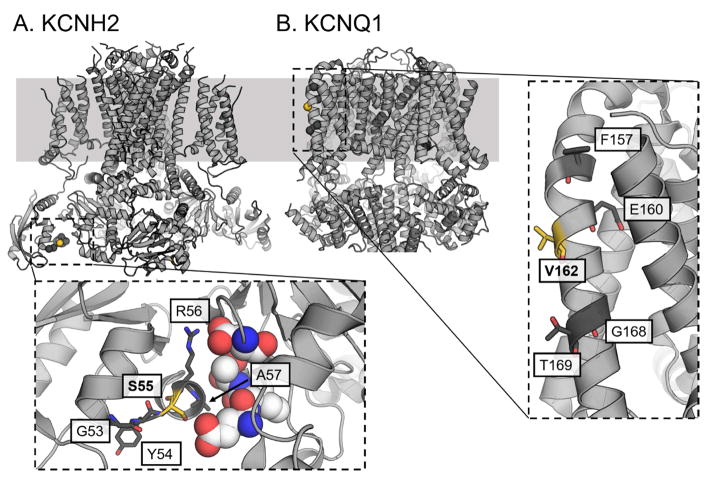

A 16-year-old female presented with an aborted sudden cardiac arrest that occurred while at rest. She had a strong family history of sudden unexplained death on her father’s side, including two aunts, one uncle, and a great grandmother (who died several weeks after giving birth). She was diagnosed with Long QT Syndrome when multiple electrocardiograms showed a corrected QT interval >500 msec without any secondary causes, and an ICD was placed. At age 24, she experienced an appropriate ICD shock one month after giving birth to her 2nd child. Evaluation in our clinic at age 27 revealed an ECG with a low amplitude, notched T-wave (QTc = 523 msec) typical of type 2 LQTS. Genetic testing identified two rare non-synonymous single nucleotide variants resulting in Ser55Leu in KCNH2 and Val162Met in KCNQ1. A CLIA-approved commercial genetic testing laboratory annotated both variants as pathogenic. Cited evidence for pathogenicity of the KCNH2 variant included 1) two publications reprorting the variant in individuals with LQTS;6, 7 2) its absence from 2088 reference alleles sequenced in the commercial laboratory; and 3) neighboring residues previously associated with LQTS (KCNH2 Gly53Arg, Gly53Asp, Gly53Ser, Tyr54His, Arg56Gln, Ala57Pro; Figure 1). Cited evidence for the pathogenicity of the KCNQ1 Val162Met variant included 1) a previous publication where the variant was found present in 1 of 2,500 individuals with LQTS;8 2) absence in more than 2600 reference alleles; and 3) proximity to neighboring residues associated with LQTS (KCNQ1 Phe157Cys, Glu160Lys, Glu160Val, Gly168Arg, Thr169Arg; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sequence context and secondary structure surrounding KCNH2 S55L and KCNQ1 V162M. Pathogenic residues highlighted from the genetic testing report (Gly53, Tyr54, Arg56, Ala57 for KCNH2 and Phe157, Glu160, Gly168, Thr169 for KCNQ1) are highlighted in black; KCNQ1 Val162 and KCNH2 Ser55 are highlighted in yellow. Secondary structure elements in the PAS domain (KCNH2) and voltage sensing domain S2 helix (KCNQ1) fragments shown above the sequences.

Following identification of the two variants, we undertook cascade screening in the remaining available family. Co-segregation analysis demonstrated that QT prolongation occurred only in the presence of the KCNH2 variant, and family members carrying the KCNQ1 variant alone were phenotypically unaffected (Figure 2), suggesting pathogenicity of KCNH2 Ser55Leu and not KCNQ1 Val162Met. As shown in Figure 3A/B, compared to WT KV11.1 (KCNH2) currents displaying prominent inward rectification, Ser55Leu currents variant showed reduction in activating and deactivating (tail) currents, causing an extreme loss-of-function phenotype, consistent with previously published trafficking results.9 Interestingly, at very positive voltages, this variant displayed an outward rectifying current component, indicating that the mutant channel clearly gates abnormally. In contrast to KCNH2 Ser55Leu, the slowly activating potassium current (IKs) traces (resulting from co-expressed gene products of KCNQ1 and KCNE1) showed no difference between WT and Val162Met as assessed by total steady-state activating and deactivating tail currents (Figure 3C/D).

Figure 2.

Pedigree of the family. Proband (arrow) and her three children all present with LQT while the proband’s sister and sister’s children all appear unaffected. The mother of the proband is KCNQ1 positive and has an ECG QTc ~450 (not shown).

Figure 3.

Functional changes of HERG variant Ser55Leu and no changes of KCNQ1 variant Val162Met on IKs. A, Summarized activating currents show that Ser55Leu variant removed inward rectification of HERG current. B. Near absence of deactivating tail current with the Ser55Leu mutant. C and D, the KCNQ1 variant Val162Met had no effects on IKs activating (C) and deactivating (D) currents.

Three-dimensional structural context of variants

To investigate in greater detail the relationship between KCNH2 Ser55Leu and KCNQ1 Val162Met and their sequence context provided as evidence of pathogenicity, we leveraged predicted and experimentally determined structures of the regions surrounding both variants. In the human KCNH2 channel, Ser55 sits at the interface between the Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) and cyclic nucleotide-binding homology (CNBH) domains (Figure 4A), both of which are known to govern inactivation.10 In the Xenopus KCNQ1 structure, Val162 is located in the N-terminal half of the S2 helix within the voltage-sensing domain. The Val162 residue in the KV7.1 model is pointed away from the center of the voltage-sensing domain (highlighted in yellow; Figure 4B) while three of four variants adjacent in sequence space and previously described as pathogenic point inward towards the center of the domain (dark grey; Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Structural interpretation of KCNH2 Ser55Leu and KCNQ1 Val162Met and neighboring reported pathogenic variants. A, KCNH2 with pathogenic residues highlighted from the genetic testing report shown as sticks and highlighted in dark gray. The variant characterized in this report shown as sticks and colored yellow. Residues from the neighboring CNBH domain are shown as spheres with carbon atoms colored white. All residues implicated in the genetic testing report, including Ser55, lie along the interface between the PAS and CNBH domains. B, Structure of Xenopus Kv7.1 (KCNQ1) with pathogenic residues highlighted from the genetic testing report as sticks in dark grey and the variant characterized in this report shown as sticks and yellow. Val162 points away from the center of the voltage sensing-domain of KCNQ1 and towards the lipid environment, in contrast to three of the four other variants cited as evidence for the classification of Val162Met as pathogenic. Thr169, cited as evidence for the Val162Met classification, also points out into the lipid environment; however, the Thr169Arg variant introduces a much larger and charged side-chain, compared to Val162Met which conserves hydrophobicity. Furthermore, another Thr169 variant, Thr169Met, is observed at too high a frequency in the general population to be canonically pathogenic suggesting the tolerance of methionine on this face of the KCNQ1 molecule (see main text).

Discussion

The clinical presentation of the proband (ECG pattern and post-partum event11) was suggestive of LQT2, and when presented with two potentially causative variants, we felt further investigation of each variant was warranted. One piece of evidence asserted by the commercial genetic testing report to support the pathogenicity of these two variants was that they were positioned near other variants thought to be pathogenic (Figure 1). However, proximity in sequence space does not always translate accurately to proximity in three-dimensional space. There is a growing appreciation for how structural information can be leveraged to interpret variants, especially in cancer.12–16 The extension of this type of analysis to broader spectrum of diseases, including inherited disorders, has been less extensive.17 The position of residue 162 in KCNQ1 combined with the relatively conservative mutation (Val to Met) suggests a minor perturbation would result from the substitution, whereas the context variants mentioned in the genetic testing report are much more likely to destabilize protein folding energetics and potentially interfere with the voltage dependence of activation (Figure 4B). Three of the four context variants provided point towards the interior of the voltage-sensing domain, Phe157, Glu160, and Gly168. Thr169, similar to Val162, points away from the protein and towards the membrane; however, the pathogenicity of the Thr169Arg mutation is likely due to the highly non-conservative nature of the residue change. In fact, a methionine at site 169, Thr169Met, is present in gnomAD at 12 alleles out of 244,924 sequenced,18 too high to be canonically pathogenic19 and suggestive of the tolerable nature of a more hydrophobic residue at this face of the helix. In contrast to this evidence, for KCNH2 Ser55Leu, all neighboring residues given as supporting evidence of pathogenicity are involved in the interaction between the PAS domain and the CNBH domain (Figure 4A). In the structure, Ser55 appears to interact with Glu857 on the CNBH domain, though the resolution precludes definitive side-chain positioning. Interaction between these two domains is thought to play a role in inactivation which may explain the increased current observed at very positive potentials.20

The initial QT morphology (low amplitude and notched) and clinical history (post-partum event) suggestive of LQT2 was further corroborated by the segregation of the clinical phenotype with genotype KCNH2 Ser55Leu positive family members (Figure 2). At the time the variants were annotated as pathogenic, there were no functional data to reference as supporting evidence of classification. The heterologous expression data we present here suggest a near complete loss-of-function KCNH2 Ser55Leu (likely due to mistrafficking as is the case for the majority of pathogenic KCNH2 mutations21), and a KCNQ1 Val162Met indistinguishable from WT.

The clinical consequence of the initial commercial genetic testing report that annotated both variants as “pathogenic” was an unwarranted ICD implantation. At the time the decision was made to implant, only the commercial report and co-segregation data were available. Despite counseling that there was weak and conflicting evidence for pathogenicity of the KCNQ1 variant, the family was uncomfortable foregoing ICD implantation in the proband’s sister, who had a QTc of 426 ms and carried only the KCNQ1 Val162Met variant. Ultimately, an ICD was implanted at another facility, and the performing physician cited the pathogenic annotation as indication for placement of an ICD due to Long QT Syndrome.

Conclusions

We show evidence by structural modeling and heterologous expression supporting the pathogenicity of the single variant KCNH2 Ser55Leu while also suggesting the non-pathogenicity of the KCNQ1 Val162Met variant. We further suggest cautious interpretation of sequence context evidence for pathogenicity. The original genetic testing report suggested both variants were pathogenic; a claim recently contested for KCNQ1 Val162Met which ClinVar downgraded to a VUS. However, using the 2015 ACMG guidelines for classifying variants, given the number of known unaffected carriers in the population, lack of functional perturbation, and putative position in the KCNQ1 molecule, the KCNQ1 Val162Met should be reclassified as benign. Correct classification of the KCNQ1 Val162Met likely would have prevented the use of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) in the proband’s sister.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants K99HL135442 (BMK), K23HL127704 (MBS), and RO1HL118952-02 (DMR)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: the authors declare no conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2. 0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2017;19:249–255. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang W, MacKinnon R. Cryo-EM Structure of the Open Human Ether-a-go-go-Related K+ Channel hERG. Cell. 2017;169:422–430. e410. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun J, MacKinnon R. Cryo-EM Structure of a KCNQ1/CaM Complex Reveals Insights into Congenital Long QT Syndrome. Cell. 2017;169:1042–1050. e1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schrodinger, LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang P, Kanki H, Drolet B, et al. Allelic variants in long-QT disease genes in patients with drug-associated torsades de pointes. Circulation. 2002;105:1943–1948. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014448.19052.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behr ER, Dalageorgou C, Christiansen M, Syrris P, Hughes S, Tome Esteban MT, Rowland E, Jeffery S, McKenna WJ. Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome: familial evaluation identifies inheritable heart disease in the majority of families. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1670–1680. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tester DJ, Will ML, Haglund CM, Ackerman MJ. Compendium of cardiac channel mutations in 541 consecutive unrelated patients referred for long QT syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapplinger JD, Tester DJ, Salisbury BA, Carr JL, Harris-Kerr C, Pollevick GD, Wilde AA, Ackerman MJ. Spectrum and prevalence of mutations from the first 2,500 consecutive unrelated patients referred for the FAMILION long QT syndrome genetic test. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1297–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson CL, Kuzmicki CE, Childs RR, Hintz CJ, Delisle BP, January CT. Large-scale mutational analysis of Kv11. 1 reveals molecular insights into type 2 long QT syndrome. Nature communications. 2014;5:5535. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haitin Y, Carlson AE, Zagotta WN. The structural mechanism of KCNH-channel regulation by the eag domain. Nature. 2013;501:444–448. doi: 10.1038/nature12487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khositseth A, Tester DJ, Will ML, Bell CM, Ackerman MJ. Identification of a common genetic substrate underlying postpartum cardiac events in congenital long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2004;1:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan L, Fuss JO, Cheng QJ, Arvai AS, Hammel M, Roberts VA, Cooper PK, Tainer JA. XPD helicase structures and activities: insights into the cancer and aging phenotypes from XPD mutations. Cell. 2008;133:789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao J, Chang MT, Johnsen HC, Gao SP, Sylvester BE, Sumer SO, Zhang H, Solit DB, Taylor BS, Schultz N, Sander C. 3D clusters of somatic mutations in cancer reveal numerous rare mutations as functional targets. Genome Med. 2017;9:4. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0393-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer MJ, Lapcevic R, Romero AE, Yoon M, Das J, Beltran JF, Mort M, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, Paccanaro A, Yu H. mutation3D: Cancer Gene Prediction Through Atomic Clustering of Coding Variants in the Structural Proteome. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:447–456. doi: 10.1002/humu.22963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niknafs N, Kim D, Kim R, Diekhans M, Ryan M, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, Karchin R. MuPIT interactive: webserver for mapping variant positions to annotated, interactive 3D structures. Hum Genet. 2013;132:1235–1243. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1325-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokheim C, Bhattacharya R, Niknafs N, Gygax DM, Kim R, Ryan M, Masica DL, Karchin R. Exome-Scale Discovery of Hotspot Mutation Regions in Human Cancer Using 3D Protein Structure. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3719–3731. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sivley RM, Kropski J, Sheehan J, Cogan J, Dou X, Blackwell TS, Phillips JA, Meiler J, Bush WS, Capra JA. Comprehensive Analysis of Constraint on the Spatial Distribution of Missense Variants in Human Protein Structures. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiffin N, Minikel E, Walsh R, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Karczewski K, Ing AY, Barton PJR, Funke B, Cook SA, MacArthur D, Ware JS. Using high-resolution variant frequencies to empower clinical genome interpretation. Genet Med. 2017 doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harley CA, Starek G, Jones DK, Fernandes AS, Robertson GA, Morais-Cabral JH. Enhancement of hERG channel activity by scFv antibody fragments targeted to the PAS domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:9916–9921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601116113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith JL, Anderson CL, Burgess DE, Elayi CS, January CT, Delisle BP. Molecular pathogenesis of long QT syndrome type 2. J Arrhythm. 2016;32:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.joa.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]