Abstract

Very limited data is present which compares completely linear stapled to handsewn cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. Primary objective was to determine whether linearly stapled (LS) anastomosis has lower clinically apparent leaks, when compared to handsewn anastomosis (HS). Secondary objectives were morbidity, mortality, overall leak and stricture rates, and presence of a symptomatic cervical stricture. This is a comparative study of 77 patients who underwent LS (n = 29) and HS (n = 48) cervical anastomosis. Anastomotic leak was found to be 19.4% (15/77). In the HS group, 27.08% (13/48) and in the LS group, 6.89% (2/29), respectively, leaked (p = 0.03), relative risk (RR)—3.93 (95% CI 1.21–15.25). 32.5% (23/77) patients remained admitted for more than 14 days. 52.1% (25/48) patients in the HS group were discharged within 14 days of surgery; whereas; 93.1% (27/29) were discharged in LS group (p = 0.001), RR—6.95 (95% CI 2.13–25.94). Overall, 90-day mortality was 7.8% (6/77). In the HS group, 8.3% (4/48) patients died while in the LS group, 6.8% (2/29) patients died (p = 0.82), RR—1.21(95% CI 0.27–5.53). In the HS group, 6.25% (3/48) patients were diagnosed with stricture compared to 6.8% (2/29) patients in the LS group (p = 0.9), RR—0.91 (95% CI 0.19–4.44). Overall stricture rate was 6.4% (5/77). Cervical anastomosis done with linear staplers has less leak rates compared to handsewn anastomosis.

Keywords: Linear stapled esophagogastric anastomosis, Completely stapled cervical anastomosis, Mechanical cervical esophagogastric anastomosis, Stapled esophagogastric anastomosis

Introduction

Surgery along with neoadjuvant therapy remains the mainstay of treatment for localized middle- and lower-third esophageal cancers [1, 2]. One of the major factors which affects treatment outcomes remains anastomotic leaks, which have been reported to be between 15 and 25% [3]. Anastomotic leak, whether in the neck or thorax, is one of the major causes of postoperative morbidity [4].

There is a paucity of published world literature comparing completely linear-stapled and handsewn cervical anastomoses, with only two retrospective studies that have focused on this aspect. End-to-end anastomosis versus end-to-side versus side-to-side, handsewn versus stapled versus hybrid*, anastomosis on anterior wall versus posterior wall of stomach, and their various combinations segregate the data leaving us with limited numbers in each subset for analysis. Therefore, deriving an unequivocal and meaningful conclusion as to the optimal technique that minimizes leak rates and morbidity remains elusive. It was this lack of robust evidence that inspired this retrospective analysis of our work, as a basis to know if the same warrants observation in a prospective controlled setting.

With the above background, we conducted this retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database from August 2012 to July 2016 with the aim to compare end-to-side linearly stapled (LS) anastomosis versus end-to-side handsewn (HS) anastomosis in the neck.

Primary objective of the study was to determine whether linearly stapled (LS) cervical anastomosis have lower rates of clinically apparent anastomotic leaks following esophagogastric anastomosis after esophagectomy for cancer, when compared to handsewn anastomosis (HS).

Secondary objectives of the study were to study the morbidity, mortality, overall leak and stricture rates, and presence of a symptomatic cervical stricture.

*Posterior layer stapled, anterior layer handsewn.

Materials and Methods

This manuscript has been written in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies [5], with the details as follows.

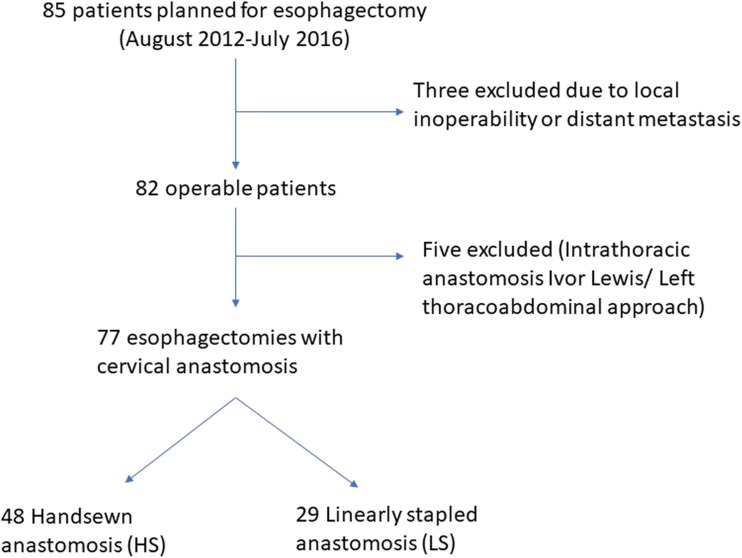

We conducted an observational study retrospectively analyzing a prospectively maintained database from August 2012 to July 2016 that included 77 patients at two different centers: Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India, and JSS Hospital, Mysore, India, to compare leak rates of linearly stapled (LS) versus handsewn (HS) cervical anastomosis, both end-to-side, in esophagectomy done for cancer (Fig. 1).

Fig.1.

Observational study

The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the “World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki-Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects” adopted by the 18th WMA General Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, June 1964, and amended in Fortaleza, Brazil, 2013 [6]. The data was collected prospectively during routine clinical practice and accordingly, signed informed consent was taken from each patient before any surgical or clinical procedure. Waiver of consent was obtained from the ethical committee of respective institutions. Literature was searched using the string (esophagogastric[All Fields] OR esophagogastric[All Fields]) AND anastomosis[All Fields] AND ((“neck”[MeSH Terms] OR “neck”[All Fields]) OR (“neck”[MeSH Terms] OR “neck”[All Fields] OR “cervical”[All Fields])) AND (handsewn[All Fields] OR mechanical[All Fields] OR stapled[All Fields] OR stapler[All Fields]) NOT (partial[All Fields] OR partially[All Fields] OR (“chimera”[MeSH Terms] OR “chimera”[All Fields] OR “hybrid”[All Fields])) AND ((Clinical Trial[ptyp] OR Comparative Study[ptyp] OR Review[ptyp] OR systematic[sb]) AND English[lang] AND cancer[sb]). Total of 13 publications were found; all the other articles used as references were either hand searched or were cross references.

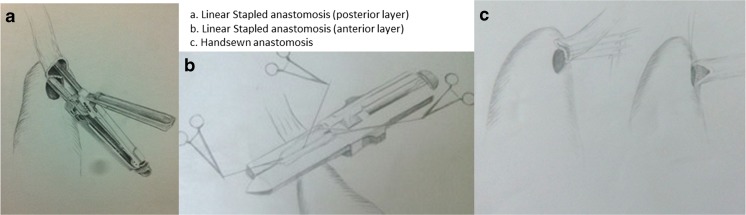

Diagnostic workup and administration of neoadjuvant therapy was as per the in-keeping with international standards and evidence-based guidelines. We specifically compared two techniques of anastomosis which have been described below (Fig. 2).

LS anastomosis was done using two 55-mm-long linear cutters of 3.8-mm (blue) limb length in an end-to-side fashion on the anterior wall of stomach.

HS anastomosis was done using single layer, simple interrupted stiches, using polyglactin 3-0, on the posterior wall of stomach in an end to side fashion. Anastomoses were done by consultant surgeons with prior experience in esophageal surgery.

Fig.2.

Two techniques of anastomosis

Postoperatively, patients were followed up clinically and any suspicion of leak was confirmed radiologically by CT scan. Morbidity and mortality: anastomotic leaks were classified as per components of definition of anastomotic leaks as described by Bruce et al. [7] (Table 1). Morbidity was considered only when the patient remained admitted for more than 14 days or was readmitted. Minor morbidities which did not prolong hospital stay for more than 14 days were not considered. Mortality included all-cause death within 90 days of surgery. During long-term follow-up, patients with dysphagia who required therapeutic dilatation were considered to have a stricture. Asymptomatic patients were not investigated for stricture.

Table 1.

Classification of leaks

| Grade | Definition | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Radiologic | Detected only on routine imaging, no clinical signs. | No change in management |

| Clinical minor | Presence of luminal contents through the drain or wound site causing local inflammation, e.g., fever (temperature > 38 °C) or leukocytosis (white cell count > 10,000/l). Leak may also be detected on imaging studies. | No change in management or intervention but may have prolonged hospital stay or delay in resuming oral intake |

| Clinical major | As clinical minor. Severe disruption of anastomosis. Leak may also be detected on imaging studies. | Change in management and intervention required |

The data has been presented in mean ± standard deviation for quantitative variables normally distributed and student’s t test has been used to find out significant difference between the mean values. Quantitative variables not normally distributed have been defined as median ± interquartile range (IQR) and Chi square test has been used as a test of significance. Qualitative variables have been presented in numbers and percentage and Z test/Fisher’s exact probability tests have been used to calculate significant difference between the proportions as per suitability. p < 0.05 was considered significant. All p values were derived from two-tailed tests. 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the difference between the proportions and the relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals to compare the two techniques for various outcome variables have also been presented. For calculation of relative risk, admission days being a continuous variable have been categorized into two groups, less than12 days and more than 12 days. Twelve is the median number of admission days for total number of cases.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in public, commercial, or not—for—profit sectors.

Results

From August 2012 to July 2016, 85 patients were explored—3 patients were inoperable due to metastases and local unresectability while in 5 patients, an intrathoracic anastomosis was performed during Ivor-Lewis/lower thoraco-abdominal approach esophagectomy, leaving behind 77 esophagectomised patients with cervical anastomoses, either handsewn or linearly stapled, both in end-to-side fashion. Descriptive data has been provided below (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive data

| Total | HS (% of n) | LS (% of n) | 95% CI of difference in proportions | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, n | 77 | 48 | 29 | |||

| M: F | 54:33 | 34:14 | 20:9 | 19.45–25% | 0.8 | |

| Mean age in years | 58.49 ± 8.1 | 58.08 ± 7.6 | 58.9 ± 9.0 | 4.7–3.09 | 0.7 | |

| Level of growth | Middle-third | 46(59.7%) | 27(56.25%) | 19(65.5%) | 15.01–31.09% | 0.4 |

| Lower-third | 31(40.3%) | 21(43.75%) | 10(34.4%) | 15.01–31.09% | ||

| Histology | SCC | 61(79.2%) | 37(77.1%) | 24(82.8%) | 16.12–23.91% | 0.5 |

| Adeno | 16(20.8%) | 11(22.9%) | 05(17.2%) | 16.12–23.91% | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Given | 38(49.4%) | 26(54.1%) | 12(41.3%) | 11.72–35.16% | 0.27 |

| Not given | 39(51.6%) | 22(45.8%) | 17(58.6%) | 11.72–35.16% | ||

| Surgery | Open TTE | 19(24.6%) | 16(33.3%) | 03(10.3%) | 0.93–39.98% | < 0.01 |

| MIS | 40(51.9%) | 16(33.3%) | 24(82.7%) | 24.91–65.91% | ||

| THE | 18(23.3%) | 16(33.3%) | 02(6.89%) | 5.07–42.65% | ||

Adeno adenocarcinoma, F female, M male, SCC squamous cell carcinoma, MIS mininally invasive surgery, THE transthoracic hiatal esophagectomy, TTE transthoracic esophagectomy

Anastomotic leak was found to be 19.4% (15/77). In the HS group, 13 out of 48 (27.08%), and in the LS group, 2 out of 29 (6.89%), respectively, leaked (p = 0.03, CI 0.51–36.24%). Eleven and 4 out of 15 leaks were grade clinical minor and major respectively according to components of definition of anastomotic leaks. Median duration of hospital stay after surgery was overall 12 days (10–15 days)—14 days (12–16 days) in the HS group and 10 days (9–11.75 days) in the LS group. Overall morbidity rates were 32.5%, i.e., 25 out of 77 patients were admitted for more than 14 days. Twnety-five out of 48 (52.1%) patients in the HS group were discharged within 14 days of surgery; whereas, 27 out of 29 (93.1%) were discharged in LS group (p = 0.001, CI 16.6–28.39%). Overall, 90-day mortality was 7.8% (6/77). In the HS group, 4 out of 48(8.3%) patients died secondary to anastomotic leak (3/4) and pulmonary complications (1/4), respectively, while in the LS group, 2 out of 29 (6.8%) patients died secondary to anastomotic leak (1/2) and pulmonary complications (1/2), respectively. The difference in 90-day mortality was not found to be significant between the HS and LS cohorts (p = 0.82, CI 16.77–15.21%). All four patients with grade III leak died. In the HS group, 3 out of 48 (6.25%) patients were diagnosed with stricture at 3 months compared to 2 out of 29 (6.8%) patients in the LS group (p = 0.9, CI 12.6–18.57%). Overall stricture rate at 3 months was 6.4% (5/77) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcome data and results

| Outcome variables | Total (77) | HS (48) | LS (29) | 95% CI of difference in proportions | p value | Relative Risk | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leak rates | 15(19.4%) | 13(27.08%) | 02(6.89%) | 0.51–36.24% | 0.03 | 3.93 | 1.21–15.25 |

| Median days of admission | 12(09–16) | 14(12–16) | 10(9–11.75) | 16.6–28.39% | < 0.001 | 2.02 | 1.36–2.97 |

| Morbidity | 25(32.5%) | 23(47.9%) | 02(6.8%) | 18.5–56.81% | < 0.01 | 6.95 | 2.13–25.94 |

| Mortality | 06(7.8%) | 04(8.3%) | 02(6.89%) | 16.77–15.21% | 0.82 | 1.21 | 0.27–5.53 |

| Stricture formation | 05(6.4%) | 03(6.25%) | 02(6.89%) | 12.6–18.57% | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.19–4.44 |

The RR of leak rates was 3.93 times higher in HS group as compared to LS with 95% CI 1.21–15.25. The median days of admission were 2.02 times higher with HS group compared to LS group, 95% CI 1.36–29.7. In the HS group, risk of morbidity was found 6.95 times higher than LS group having 95% CI 2.13–25.94 (Table 3).

Discussion

A review of literature found only two retrospective studies [8, 9] which compared completely linear stapled anastomosis to handsewn anastomosis in the neck, while all other studies included the hybrid technique or use of circular stapler in the “stapled anastomosis” cohort [10–15] or included intrathoracic site of anastomosis [3, 16], precluding comparison to our study. Singh et al. [9] studied 93 patients out of which 43 underwent handsewn anastomosis, 34 underwent stapled anastomosis, and remaining 16 had partially stapled hybrid anastomosis. Similar to our observation, they showed significantly reduced leak and stricture rates in the stapled group, i.e., 23 vs. 3% (p < 0.05) and 58 vs.18% (p < 0.05) respectively. However, one difference in their technique was that they did not form a stomach tube and pulled up a non-tubularised stomach in the neck.

In the review by Price et al. [8], 164 patients out of 432 esophagectomies underwent cervical anastomoses - 83 LS and 14 HS anastomosis while the remaining 67 had hybrid or partially stapled anastomosis. They also concluded increased odds for leak with handsewn anastomosis compared to fully stapled anastomosis i.e. 64.3% vs. 13.2% (p = 0.001). They noted a non-significant difference in stricture rates between HS and LS anastomoses (35.1 vs. 21.5%, p = 0.92), with the fully stapled cohort having a lower stricture rate.

Though our stricture rates do not parallel our leak rates, all our patients who developed strictures had clinical evidence of anastomotic leak in the perioperative period as seen in the two studies by Singh et al. [9] and Price et al. [8].

Increased morbidity in HS group is clearly seen to reflect increased leak rates. All patients with anastomotic leak had hospital stay more than 14 days. Five out of 13 leaks in HS group had intrathoracic collection explaining the morbidity. All leaks were managed by drainage either in the neck or by CT-guided drain placement.

An interesting observation is the significant reduction in operative time in the stapled cohort as noted in the study by Saluja et al. [11], where they used the partially stapled or hybrid technique where only one layer of the anastomosis is stapled. Though we performed a fully stapled anastomosis in our study, our data on duration of surgery was incomplete. A faster stapled anastomosis is fathomable; assuming the swiftness of the anastomosis may be another factor that improved leak rates by reducing the exposure to anesthetic agents and intraoperative fluctuation of blood pressure.

A stapled anastomosis also theoretically eliminates the margin of human error in surgical technique towards the fag end of long surgery. This may be a corollary from the observation that that transhiatal esophagectomy has a trend towards reduced leak rates compared to Mckeown’s three-stage procedure, where the latter is found to have a comparatively prolonged duration of surgery. Another hypothesis for lower leaks rates historically in transhiatal esophagectomies may be that all transhiatal esophagectomies were performed for patients with lower-third and GE junction tumors requiring wider margins at the fundus resulting in a shorter tube formation and hence lower chances of fundal ischemia. We noted a 22.03% leak rate in the transthoracic group versus 11.1% in the transhiatal group; however, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.49, CI 15.73–26.85%).

In our series, all 77 anastomoses were performed by three surgeons adequately trained in esophageal surgery but there is literature to suggest that anastomosis performed by trainees and residents under supervision of senior surgeons have similar outcomes [17]. Also, stapled anastomosis does help in standardization of technique across continents which help in obtaining better research-oriented results as it reduces interpersonal bias.

Manometric studies [18] on the two techniques of anastomosis showed that the mean diameter of anastomosis in the handsewn group was 1.67 and 1.70 cm in patients with and without dysphagia respectively. These dimensions were 3.000 and 3.014 cm for the stapled group with and without dysphagia respectively. This observation does raise concern, if at all diameter of the anastomosis above a critical level plays a role in the clinical presentation of dysphagia and warrants further research.

As with all the retrospective studies, this study also has its limitations of numbers and study design. Firstly, data is not homogenous between the two cohorts, i.e., in the HS group, there is equal distribution of cases between the three types of surgeries performed in the group, i.e., 33% (16 of 48 patients) underwent transthoracic, minimally invasive, and transhiatal esophagectomy; whereas, in the LS group, majority of the surgeries performed were by minimally invasive techniques which is inherently known to have lower morbidity and hospital stay probably explaining the similar results in our studies.

Secondly, our incomplete data on factors such as blood loss, hemoglobin levels, serum albumin, pulmonary function tests (forced expiratory volume at 1 s) and comorbidities, which are known to affect the leak rates in esophageal cancer patients, precluded any possible regression analysis to know if the technique of stapling truly affected outcomes [19]. Tabatabai et al. [19] demonstrated serum albumin levels less than 3.5 g/dl as one of the significant factors leading to leak. Other factors found significant were FEV1 less than 2 l, increased blood loss during surgery, and pulmonary complications. Aminian et al. [20] demonstrated increased leak rates in patients with diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

Conclusion

In the light of above data, authors conclude that a total mechanical cervical anastomosis done with linear staplers has less leak rates compared to handsewn anastomosis. While all stricture patients do have clinical evidence of perioperative leak, vice versa does not hold true, i.e., all anastomotic leaks may not develop strictures.

As this is a retrospective study, a randomized control trial with adequate sample size is proposed to derive practice changing-results.

References

- 1.D’Journo XB, Thomas PA. Current management of esophageal cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(Suppl 2):S253–S264. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.04.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, Zalcberg JR, Simes RJ, Barbour A, Gebski V, Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(7):681–692. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng X-F, Liu Q-X, Zhou D, Min J-X, Dai J-G. Hand-sewn vs linearly stapled esophagogastric anastomosis for esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2015;21(15):4757–4764. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu Q-R, Wang K-N, Wang W-P, Zhang K, Chen L-Q. Linear stapled esophagogastrostomy is more effective than hand-sewn or circular stapler in prevention of anastomotic stricture: a comparative clinical study. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2011;15(6):915–921. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1490-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.STROBE Statement: Home [Internet]. [cited 2016 Dec 25]. Available from: http://strobe-statement.org/index.php?id=strobe-home

- 6.WMA Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2016 Dec 25]. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/

- 7.Bruce J, Krukowski ZH, Al-Khairy G, Russell EM, Park KG. Systematic review of the definition and measurement of anastomotic leak after gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88(9):1157–1168. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price TN, Nichols FC, Harmsen WS, Allen MS, Cassivi SD, Wigle DA, Shen KR, Deschamps C. A comprehensive review of anastomotic technique in 432 esophagectomies. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(4):1154–1160-1161. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh D, Maley RH, Santucci T, Macherey RS, Bartley S, Weyant RJ, Landreneau RJ. Experience and technique of stapled mechanical cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(2):419–424. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(00)02337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W-P, Gao Q, Wang K-N, Shi H, Chen L-Q. A prospective randomized controlled trial of semi-mechanical versus hand-sewn or circular stapled esophagogastrostomy for prevention of anastomotic stricture. World J Surg. 2013;37(5):1043–1050. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1932-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saluja SS, Ray S, Pal S, Sanyal S, Agrawal N, Dash NR, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Randomized trial comparing side-to-side stapled and hand-sewn esophagogastric anastomosis in neck. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2012;16(7):1287–1295. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valverde A, Hay JM, Fingerhut A, Elhadad A. Manual versus mechanical esophagogastric anastomosis after resection for carcinoma: a controlled trial. French Associations for Surgical Research. Surgery. 1996;120(3):476–483. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(96)80066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laterza E, de’ Manzoni G, Veraldi GF, Guglielmi A, Tedesco P, Cordiano C. Manual compared with mechanical cervical oesophagogastric anastomosis: a randomised trial. Eur J Surg Acta Chir. 1999;165(11):1051–1054. doi: 10.1080/110241599750007883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu H-H, Chen J-S, Huang P-M, Lee J-M, Lee Y-C. Comparison of manual and mechanical cervical esophagogastric anastomosis after esophageal resection for squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg Off J Eur Assoc Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2004;25(6):1097–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q, He X-R, Shi C-H, Tian J-H, Jiang L, He S-L, Yang KH. Hand-sewn versus stapled esophagogastric anastomosis in the neck: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Indian J Surg. 2015;77(2):133–140. doi: 10.1007/s12262-013-0984-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walther B, Johansson J, Johnsson F, Von Holstein CS, Zilling T. Cervical or thoracic anastomosis after esophageal resection and gastric tube reconstruction: a prospective randomized trial comparing sutured neck anastomosis with stapled intrathoracic anastomosis. Ann Surg. 2003;238(6):803–812-814. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000098624.04100.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Handagala SDM, Addae-Boateng E, Beggs D, Duffy JP, Martin-Ucar AE. Early outcomes of surgery for oesophageal cancer in a thoracic regional unit. Can we maintain training without compromising results? Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg Off J Eur Assoc Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2012;41(1):31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng B, Wang R-W, Jiang Y-G, Tan Q-Y, Zhao Y-P, Zhou J-H, Liao XL, Ma Z. Functional and menometric study of side-to-side stapled anastomosis and traditional hand-sewn anastomosis in cervical esophagogastrostomy. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg Off J Eur Assoc Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2009;35(1):8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabatabai A, Hashemi M, Mohajeri G, Ahmadinejad M, Khan IA, Haghdani S. Incidence and risk factors predisposing anastomotic leak after transhiatal esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Med. 2009;4(4):197–200. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.56012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aminian A, Panahi N, Mirsharifi R, Karimian F, Meysamie A, Khorgami Z, et al. Predictors and outcome of cervical anastomotic leakage after esophageal cancer surgery. J Cancer Res Ther. 2011;7(4):448–453. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.92016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]