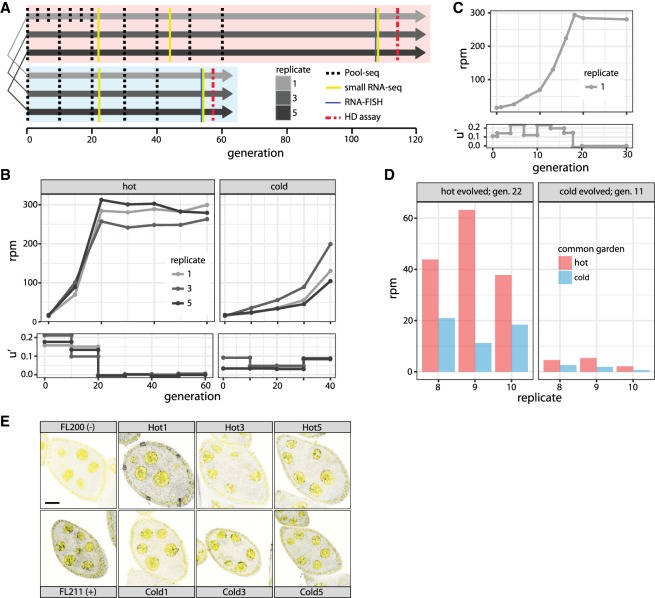

Figure 1.

Overview of a natural P-element invasion in experimentally evolving D. simulans populations. (A) Experimental design. Three replicates were kept at hot and cold conditions using nonoverlapping generations. Replicates with the same index in hot and cold conditions are derived from the same parents. Note that flies in cold conditions develop slower. (B) P-element abundance in rpm (reads mapping to the P-element out of a million mapped reads; upper panel) and effective transposition rate (u′; lower panel) during the hot and cold invasion. (C) High-resolution view of the hot invasion in replicate 1. The invasion plateaus at generation 18. (D) RNA-seq shows differences in P-element expression between hot and cold conditions. We transferred flies from the hot invasion at generation 22 and from the cold invasion at generation 11 to both a hot and a cold common garden. P-element expression is consistently lower under cold conditions. (E) Sense transcripts of the P-element are expressed in D. simulans ovaries. We dissected flies from the hot invasion (Hot; index indicates replicate) at generation 108 and from the cold invasion (Cold) at generation 54 and performed single RNA-FISH using a set of Stellaris oligo probes to detect sense transcripts of the P-element (black dots). DAPI is shown in yellow. As a positive (+) and a negative control (−), we included ovaries from flies with and without the P-element, respectively (Hill et al. 2016). Scale bar, 20 µm.