Abstract

Background:

Podcasts have become an integral part of Free Open Access Medical education. After only 1 year since launching the Anesthesia and Critical Care Reviews and Commentary (ACCRAC) podcast, more than 7000 people were listening to unique content monthly. The study goal was to capture the listeners' views of their use of educational podcasts in general and of the ACCRAC podcast in particular.

Methods:

After institutional review board exempt status was obtained, a request was posted on the ACCRAC site inviting users to participate in an anonymous survey. The cross-sectional survey of listeners included 18 items and was open for 2 months between April and June, 2017.

Results:

A total of 279 listeners of this podcast responded with a 43% response rate. Of those, 196 (71%) were between the ages of 25 and 34, and 153 (56%) indicated that podcasts were the most beneficial education modality outside formal didactics. About half, 128 (47%), reported using podcasts 1 to 2 times per week, and 88 (32%) listened at least 3 times per week. Listeners indicated that on average they had heard 18 episodes (SD = 11.7, 40 total) in this series, and over 90% reported high levels of satisfaction with the podcast.

Conclusions:

The popularity of the podcast indicates a clear need for this type of educational modality in anesthesiology. The results suggest that there is a demand for podcasts among learners and that those who listen to podcasts do so frequently and value them because they support multitasking and provide flexible access to pertinent information.

Keywords: medical education, podcast, learner centered

Introduction

In emergency medicine, a robust culture has grown around the idea of Free Open Access Medical education. Podcasts - audio recordings on relevant topics - are an integral part of this culture. Between 2002 and 2013, the number of podcasts in emergency medicine alone increased from 1 to 42, and many have become extremely popular.1 For example, 80% of emergency medicine residents report listening to the Emergency Medicine Reviews and Perspectives (EM:RAP) podcast regularly.2

This culture has not taken root in anesthesiology to the same extent that it has in emergency medicine for reasons that are not clear but that may include the fact that many podcasts in anesthesiology are not frequently updated or are no longer updated at all (see Table 1). One study found a total of 22 anesthesiology themed podcasts between 2005 and 2016.3 This study reported that only 6 out of 22 podcasts were still active in 2016 and that the median longevity of the podcasts was 13 months. Podcasts have been available for a similar amount of time in both emergency medicine and anesthesiology specialties as have competing formats such as audio digests, weblogs (blogs), RSS (really simple syndication) feeds, and wikis. However, 1 study of Canadian anesthesiology residents found that a high percentage used podcasts, many at least an hour each week and sometimes up to an hour each day.4

Table 1.

Anesthesia Themed Podcasts Not Recently Updated a

The popularity of podcasts may be due, in part, to the fact that resident physicians are struggling to find ways to balance learning, service, and their personal lives. Podcasts allow them to learn while exercising or commuting, without adding any additional time to their already busy day. Mallin and colleagues2 wrote that podcasts, along with other forms of asynchronous learning such as blogs and iTunes videos, are changing the face of medical education. They cite a belief in emergency medicine that “traditional texts are dead.” Seventy percent of emergency medicine residents said that podcasts were the most useful form of asynchronous education that they used, though the authors did not attempt to correlate this with standardized test scores or competency in patient care.2

In April of 2016 one of the authors (JW) started a free and openly available podcast called Anesthesia and Critical Care Reviews and Commentary (ACCRAC). The podcast focuses on a wide variety of topics related to both anesthesiology and critical care medicine. Episodes are recorded and posted online by the author (JW). Topics are chosen by the creator (JW) based on listener requests and availability of experts for interviews. Listeners who subscribe to the podcast on a podcast app are notified by their app when there is a new episode and listeners who sign up for the ACCRAC mailing list are also notified via that list. There is no advertising on the site and no funding for the project. All maintenance fees are paid by the founder (JW). In the first year, 40 episodes were produced that ranged in length from 20 minutes to 1 hour.

Given that in April 2017, Google analytics (Google, LLC, Mountain View, California) showed more than 7000 unique listeners each month, this study was conducted to capture the views of ACCRAC podcast listeners about podcasts in general and about the ACCRAC podcast specifically and to analyze the demographic breakdown of these 7000 listeners. We hypothesized that the majority of listeners would be anesthesiology residents, who prefer podcasts over other forms of learning, and who find the ACCRAC podcast to be useful for their learning.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional survey of the ACCRAC podcast users from April 1 to June 2, 2017.

Survey Tool

We developed the initial survey items based on a review of related literature to address our hypotheses following questionnaire development guidelines for educational research.5 The online survey was created using Qualtrics software (http://www.qualtrics.com Qualtrics, Provo, Utah). The initial survey was pilot tested by 7 local users of the ACCRAC podcast series. Based on the pilot test feedback, 3 items were revised for clarity and 1 item was added to allow researchers to differentiate between participants affiliated with their own institution and those who were not in order to detect any potential bias. The final survey included a total of 17 items within 3 main sections: demographics, overall podcast use in education, and satisfaction with the ACCRAC podcast series. It also included a free-text item for participants to provide open-ended feedback. (See Appendix A for the final survey tool.)

Data Collection

After obtaining an exempt status from the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board, 1 of the researchers (JW, ACCRAC host and creator) posted an episode with a request on the ACCRAC site inviting users to participate in an online anonymous survey in April 2017, which was the 1-year anniversary of the ACCRAC podcast. Google analytics indicated an increasing listenership throughout the year for this podcast series, which had reached 7000 unique monthly listeners. The authors hoped that this large listener base could provide valuable insights into the educational use of this modality. This request was repeated in a new podcast episode 1 week after opening the survey. The survey announcement was kept on the podcast site for 2 months between April and June, 2017. Towards the end of the 2-month period, there were no more new responses for 2 weeks and the survey was closed at that time. Using Google analytics, we were able to see how many people listened to these 2 episodes during these 2 months and therefore to know how many people heard the invitation to take the survey.

Quantitative Data Analysis

The survey data were exported to Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) for analysis. Categorical data were presented in frequencies (and percentages), and numerical data were provided as means (and standard deviations). Categorical data were compared by χ2 test or Fisher exact test where appropriate. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Charts were also generated in Microsoft Excel.

Analysis of Open-ended Feedback:

Thematic analysis was applied inductively using qualitative data analysis software, NVivo for Mac (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11. 3.2, 2016, Melbourne, Australia), to look for common themes in the open-ended responses provided by the participants. Thematic analysis provides a flexible qualitative analytic method to recognize patterns in the data with or without predetermined themes.6 In the current study, there were no predetermined themes as the free-text item was open-ended and seeking participants' overall feedback.

Results

As of June 2017, 45 episodes of the ACCRAC podcast were available, covering topics such as airway physiology, use of sodium bicarbonate in lactic acidosis, and anesthesia for liver transplants. Google analytics showed that the podcast (all 45 episodes combined) was downloaded by nearly 7000 unique listeners each month.

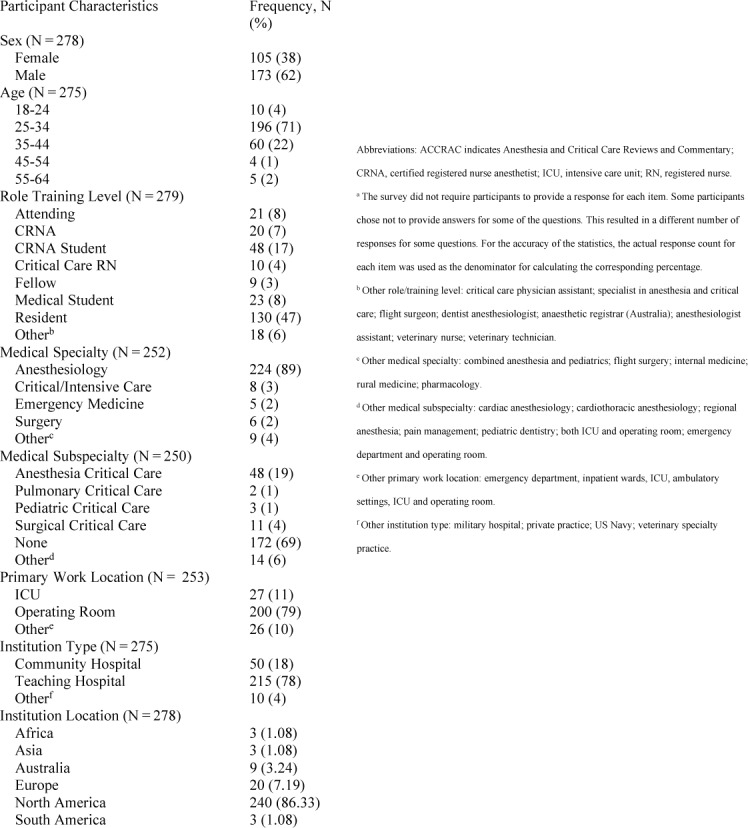

During the study period, a total of 650 users downloaded the specific 2 episodes where the survey announcement was made. A total of 279 listeners of this podcast completed the survey with a 43% response rate. Of those, 173 (62%) were male, 130 (47%) were residents, and 196 (71%) were between the ages of 25 and 34. Respondents were from various medical specialties such as intensive care, emergency medicine, and surgery; however, the majority, 224 (89%), were in anesthesiology practice. Most respondents indicated that they were affiliated with a teaching hospital, 215 (78%), and that they worked in the operating room, 200 (79%). Although 240 (86%) were from the North America, there were listeners from all continents except Antarctica (Table 2). The survey did not require participants to provide a response for each item. Those listeners who decided to participate in the survey could choose not to provide answers for any of the questions if they did not want to. Some participants chose not to provide answers for some of the questions. This resulted in a different number of responses for some questions. For the accuracy of the statistics, the actual response count for each item was used as the denominator for calculating the corresponding percentage.

Table 2.

Demographics – ACCRAC Podcast Survey Participants

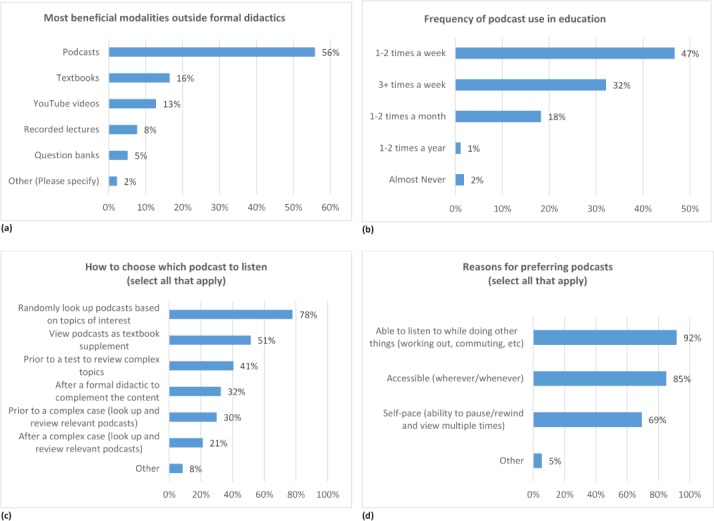

A total of 274 listeners responded to the survey items related to overall podcast use in education. Figure 1 shows the summary results for these items. Of the 274 respondents, 153 (56%) indicated that podcasts were the most beneficial education modality outside formal didactics (Figure 1.a). About half, 128 (47%), reported using podcasts 1 to 2 times per week, while 88 (32%) stated that they listened to podcasts at least 3 times per week in their education (Figure 1.b).

Figure 1:

Proportion of responses regarding overall use of podcast for medical education.

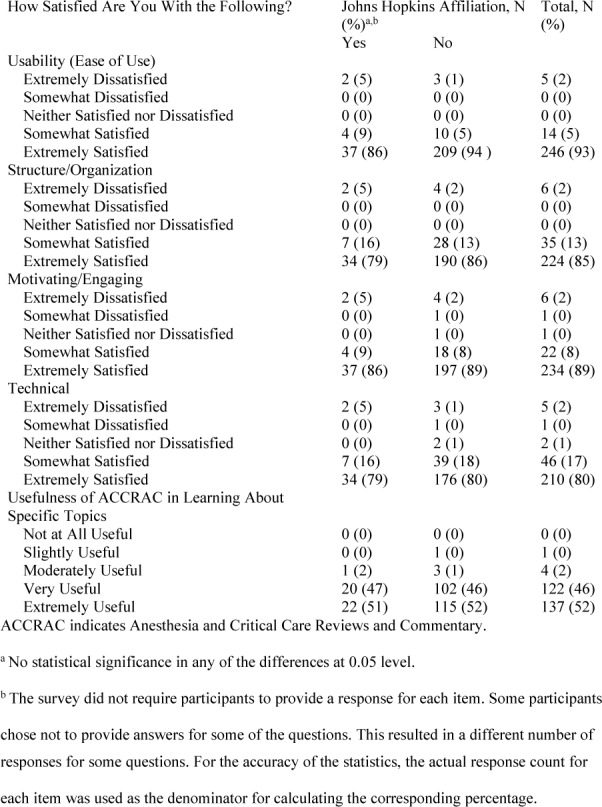

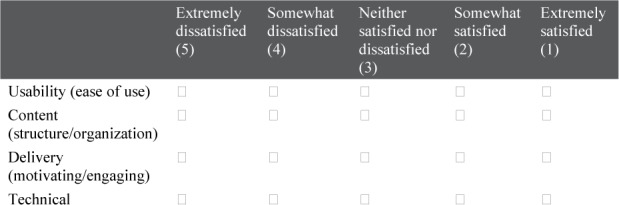

Fifty-six percent (153) of participants discovered the ACCRAC podcast through either iTunes/podcast app search or Google search, whereas 40% (109) reported that a colleague or professor had recommended this podcast series. Respondents indicated that on average they had listened to 18 episodes (SD = 11.7; range, 1 to 40) in this series, and over 90% reported high levels of satisfaction with the quality and usefulness of the podcast (Table 3). Responses provided by those affiliated with Johns Hopkins were reported separately to provide comparison for any potential bias.

Table 3.

Satisfaction With ACCRAC Podcast – A Comparison Between Respondents Affiliated With Johns Hopkins and Those Unaffiliated With Johns Hopkins

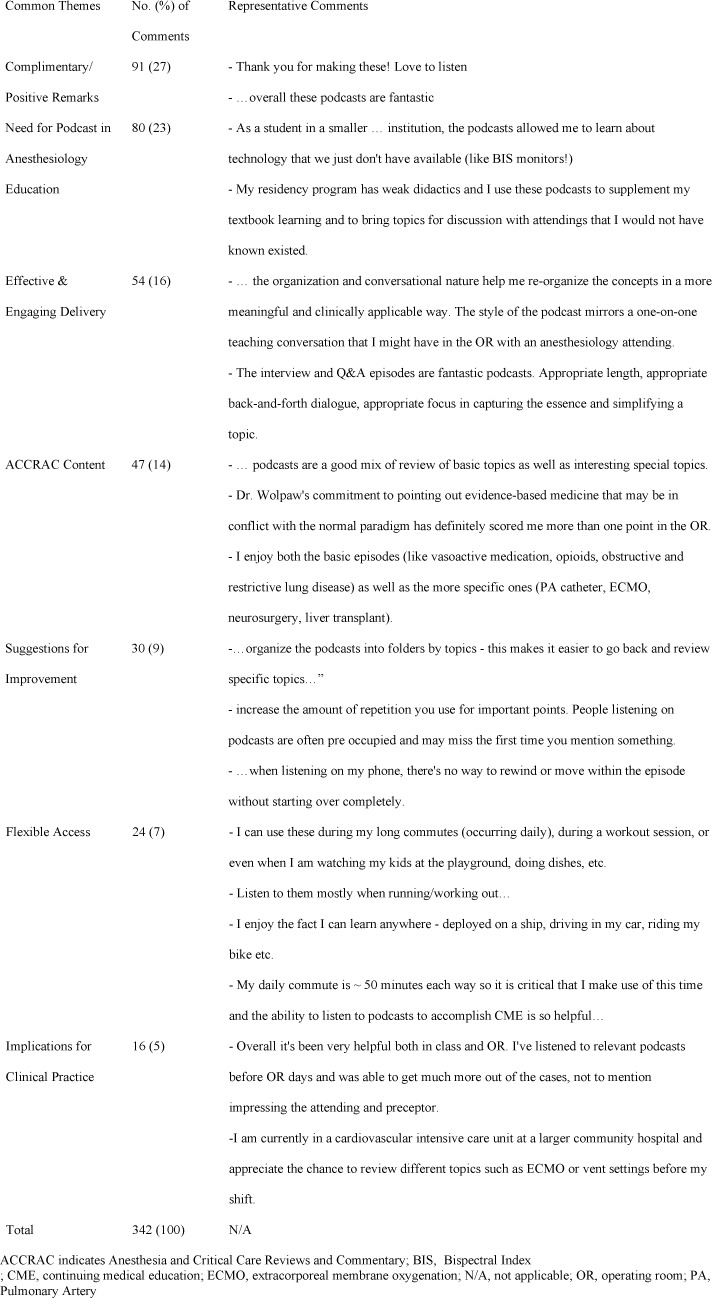

Many participants, 179 (64%), chose to respond to the free-text item regarding their overall impression of ACCRAC. Table 4 summarizes the findings of the qualitative analysis. The percentages in Table 4 are relative frequencies. Total number of coded comments (342) served as the denominator when calculating the relative frequency of each specific theme. Common themes that emerged included complimentary/positive remarks, need for podcast in anesthesiology education, effective and engaging delivery (teaching style), comments about podcast content, suggestions for improvement, flexible access, and implications for clinical practice. (Please see Table 4 for representative comments corresponding to each of the common themes.)

Table 4.

Common Themes

Discussion

In creating and studying the ACCRAC podcast, we have shown that there is a significant desire for this format of learning, especially among anesthesiology residents. We found that learners who listen to podcasts use them often, and that at least 1 specific podcast, the ACCRAC podcast, is highly regarded and extensively used by trainees. Our findings were confirmed by quantitative responses to the survey questions and by the themes that emerged in the qualitative data. We therefore confirmed our 3 hypotheses. We found that the majority of listeners are anesthesiology residents, who prefer podcasts over other forms of learning, and who find the ACCRAC podcast to be useful for their learning.

In just over a year, ACCRAC podcast has developed a worldwide listenership of more than 7000 listeners each month, and though most listeners are residents, it appeals to a wide array of healthcare providers from medical students to nurses and attendings. The popularity of the podcast among residents lends support to the findings by Matava and colleagues4 that anesthesiology residents are using this method of learning more and more. Their survey of anesthesiology residents in Canada found that 60% used medical podcasts. Of those who did, 67% listened for at least 1 hour each week.

Forty-seven percent of our respondents were residents. If this number represents a consistent proportion of all 7000 unique monthly listeners, then thousands of anesthesiology residents worldwide may be listening to this 1 anesthesiology and critical care themed podcast each month. Hence, the podcast represents an opportunity to reach anesthesiology residents in a way and on a scale that could be truly impactful. Program directors and others who design educational content for anesthesiology residents should consider offering the material in podcast form either by utilizing the ACCRAC podcast for their residents or by creating additional content of their own. Recording and distributing podcasts cost relatively little and recording a podcast takes only slightly more time than giving a lecture. Additionally, once a podcast is made, if it is posted publically, it can benefit a much wider audience than 1 set of residents in 1 lecture hall.

As our study showed, those who use podcasts listen frequently, with 79% listening to at least 1 episode per week and 32% listening 3 or more times per week. They prefer podcasts over textbooks for a variety of reasons, including the ability to listen while accomplishing other things, such as working out or commuting (92%) (Figure 1.d). Thus, they can engage in learning without adding time to their already busy day. Perhaps residents who do not have time to read textbooks - or are not willing to sacrifice the small amount of time that they have with their families - may be willing to listen to a podcast containing the same material that was in the textbook chapter.

Andrade7 showed that learners retain more information when they are doing something mindless that does not require higher order thinking skills, like doodling, than when they are not, and multiple studies have shown that aerobic exercise, especially immediately after learning, increases retention.8 The routine activity of commuting along a known route could, in theory, serve the same purpose as doodling, and exercising while learning could have similar or even better effect on retention than exercising after learning. Future studies could evaluate differences in knowledge retention between those who listen to a podcast while jogging and those who read a textbook while idle, as well as differences between those who listen to a podcast while exercising and those who do so while sitting still. Studies could also examine whether learners who use podcasts more often do better on standardized exams such as the Anesthesia In Training Exam and the Anesthesia Knowledge Test. Additionally, because podcasts can be listened whenever a learner wishes to listen, they can provide spaced learning and repetition in a way that an in-person lecture cannot.

Indeed, Vasilopoulos and colleagues9 found that anesthesiology residents and medical students showed greater improvement in interpreting electroencephalograms after listening to a podcast about it than did a control group that received a traditional didactic session only. They also found that participants with more prior exposure to podcasts had even greater improvements in their learning. These findings would suggest that today's trainees, many of whom use podcasts regularly, would have the greatest benefit from increasing podcast use for their education.

Recommendations for length of educational podcasts have ranged from 5 to 30 minutes in various commentaries and editorials. In a survey of Canadian anesthesia residents, most preferred podcasts less than 30 minutes.4,10 ACCRAC podcast episodes vary from 20 to 60 minutes, and most average approximately 45 minutes. The popularity of these podcasts would suggest that residents can enjoy listening to longer content, perhaps because they can stop and start as many times as needed.

It is tempting to attribute the popularity of podcasts in today's learners to a preference for an auditory learning style. However, studies have repeatedly found a lack of evidence for the premise that some people learn better through one style compared to another.11 Therefore it is likely that the convenience of podcasts, and learners' increasing comfort with them, plays more of a role in their popularity than a difference in learning style.

Our study had several limitations. First and foremost, by offering our survey on the ACCRAC website, we surveyed only people who already listen to ACCRAC. Thus, we cannot say what percentage of anesthesiology residents in this or any country use this podcast. Additionally, it is not surprising that respondents tended to like podcasts and prefer them to other methods of learning since they came to the survey by being podcast listeners. Finally, retrospective surveys are subject to recall bias.

Conclusions

One year after its creation, more than 7000 anesthesiology learners and providers each month listen to the ACCRAC podcast. The majority are residents who prefer podcasts to traditional forms of learning and who found the ACCRAC podcast to be extremely useful for their learning. The findings should encourage future efficacy studies with randomized controlled design to determine the merit of podcast learning with respect to actual learning outcomes. Such studies could provide evidence base and guidance for the creation of future podcast content in anesthesiology to effectively meet what is clearly a demand from our learners.

Abbreviations

- BIS

Bispectral Index

- PA

Pulmonary Artery

Appendix

Appendix A: Survey Tool

Dear Participant,

You are invited to participate in this survey because you have been identified as a one of the users of the ACCRAC podcast series created by Dr. Jed Wolpaw. The purpose of this survey is to seek your feedback about the use of podcasts in your education beyond formal didactics and specifically about your satisfaction with this podcast series.

Your participation in this survey is voluntary. You may choose not to participate. If you decide to participate in this survey, you may withdraw at any time. If you decide not to participate in this study, or if you withdraw from participating at any time you will not be penalized. Below is a link (red button) to the online survey. This survey is completely anonymous. Responses will be reported in aggregated format. The survey is brief and you should be able to complete it within 5 minutes.

We really appreciate your willingness to participate and value your feedback. Our hope is that this will help us refine and improve future podcasts.

Your completion of this survey will serve as your consent to be in this research study.

Q1 What is your level of training?

○ Attending

○ Resident

○ Fellow

○ CRNA

○ Critical care RN

○ Other RN

○ Medical Student

○ CRNA student

○ Other (Please specify) ____________________

Condition: Medical Student Is Selected. Skip To: What is your medical school year?

Display This Question:

If What is your level of training? Attending Is Selected

Q1Attending How many years have you been in practice (post-training)?

______ Using the slider below, please indicate your years in practice.

Display This Question:

If What is your level of training? Resident Is Selected

Q1Resident What is your post graduate year?

○ Select one

○ PGY1

○ PGY2

○ PGY3

○ PGY4

○ PGY5

○ PGY6

○ PGY7

○ > PGY7

Display This Question:

If What is your level of training? CRNA Is Selected

Q1CRNA What is your year of practice?

______ Using the slider below, please indicate your years in practice.

Display This Question:

If What is your level of training? Critical care RN Is Selected

Q1CritRN What is your year of practice?

______ Using the slider below, please indicate your years in practice.

Display This Question:

If What is your level of training? Other RN Is Selected

Q1RN What is your year of practice?

______ Using the slider below, please indicate your years in practice.

Q2 What is your medical specialty

○ Anesthesiology

○ Internal medicine

○ Pediatrics

○ Surgery

○ Other (please specify) ____________________

Q3 What is your medical sub-specialty?

○ Anesthesia critical care

○ Pulmonary critical care

○ Pediatric critical care

○ Surgical critical care

○ None

○ Other (please specify) ____________________

Q4 Where do you work primarily?

○ ICU

○ Operating room

○ Other (please specify) ____________________

Display This Question:

If What is your level of training? Medical Student Is Selected

Q1MedStu What is your medical school year?

○ Select one

○ Year 1

○ Year 2

○ Year 3

○ Year 4

○ Year 5

○ Year 6

Q5 What is your gender?

○ Male

○ Female

Q6 What is your age?

○ Select one

○ Under 18

○ 18–24

○ 25–34

○ 35–44

○ 45–54

○ 55–64

○ 65–74

○ 75–84

○ 85 or older

Q7 Where is your institution located?

○ Africa

○ Asia

○ Australia

○ Europe

○ North America

○ South America

Q8 With what type of institution are you affiliated?

○ Teaching hospital

○ Community hospital

○ Other (Please specify) ____________________

Q9 Are you affiliated with Johns Hopkins?

○ Yes

○ No

Q10 Which of the following is the most beneficial for you outside formal didactics (choose only one)?

○ Podcasts

○ Recorded lectures

○ Textbooks

○ YouTube videos

○ Other (Please specify) ____________________

Q11 How frequently do you use podcasts in your education (outside formal didactics)?

○ Almost Never

○ 1–2 times a year

○ 1–2 times a month

○ 1–2 times a week

○ 3+ times a week

Q12 How do you choose which podcast to listen to at a given time (select all that apply)?

□ Prior to a complex case (look up and review relevant podcasts)

□ After a complex case (look up and review relevant podcasts)

□ After a formal didactic to complement the content

□ Prior to a test to review complex topics

□ View podcasts as textbook supplement

□ Randomly look up podcasts based on topics of interest

□ Other (Please specify) ____________________

Q13 What are the reasons that you prefer podcasts (select all that apply)?

□ Accessible (wherever/whenever)

□ Self-pace (ability to pause/rewind and view multiple times)

□ Able to listen to while doing other things (working out, commuting, etc)

□ Other (please specify) ____________________

Please answer the following questions based on your experience using the podcast series created by Dr. Wolpaw.

Q14 How did you find out about this podcast (created by Dr. Wolpaw)?

○ A colleague recommended

○ My professor/program director recommended

○ ITunes or podcast app search

○ Google search

○ Other (please specify) ____________________

Q15 How many episodes of this podcast have you listen to so far?

______ Number of ACCRAC podcast listened

Q16 How satisfied are you with these podcasts based on the following?

Q17 How useful were the podcast episodes you listened to in this series in learning about the specific topics?

○ Not at all useful

○ Slightly useful

○ Moderately useful

○ Very useful

○ Extremely useful

QFeedback Could you please provide us with your overall feedback for the podcast episodes created by Dr. Wolpaw?

Footnotes

The authors report no external funding source for this study.

The authors have no conflicts/competing interests regarding this manuscript.

This study was previously presented as a poster at the 2017 American Society of Anesthesiologists Annual Meeting in Boston, Massachusetts.

References

- 1. Cadogan M, Thoma B, Chan TM, Lin M.. Free Open Access Meducation (FOAM): the rise of emergency medicine and critical care blogs and podcasts (2002–2013). Emerg Med J. 2014; 31 e1: e76– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mallin M, Schlein S, Doctor S, Stroud S, Dawson M, Fix M.. A survey of the current utilization of asynchronous education among emergency medicine residents in the United States. Acad Med. 2014; 89 4: 598– 601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh D, Alam F, Matava C.. A critical analysis of anesthesiology podcasts: identifying determinants of success. JMIR Med Educ. 2016; 2 2: e14 doi:10.2196/mededu.5950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matava CT, Rosen D, Siu E, Bould DM.. eLearning among Canadian anesthesia residents: a survey of podcast use and content needs. BMC Med Educ. 2013; 13: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Artino Jr AR, La Rochelle JS, Dezee KJ, Gehlbach H.. Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE Guide No 87. Med Teach. 2014. June 1; 36 6: 463– 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braun V, Clarke V.. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2014; 9: 26152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andrade J. What does doodling do? Appl Cogn Psychol. 2010; 24 1: 100– 6. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hötting K, Schickert N, Kaiser J, Röder B, Schmidt-Kassow M.. The effects of acute physical exercise on memory, peripheral BDNF, and cortisol in young adults. Neural Plast. 2016; 2016: 6860573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vasilopoulos T, Chau DF, Bensalem-Owen M, Cibula JE, Fahy BG.. Prior podcast experience moderates improvement in electroencephalography evaluation after educational podcast module. Anesth Analg. 2015; 121 3: 791– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cosimini MJ, Cho D, Liley F, Espinoza J.. Pod-casting in medical education: how long should an educational podcast be? J Grad Med Educ. 2017; 9 3: 388– 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pashler H, McDaniel M, Rohrer D, Bjork R.. Learning styles: concepts and evidence. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2008; 9 3: 103– 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]