Abstract

Background

Addressing factors leading to health disparities in the Circumpolar North require approaches that consider and address the social determinants of health including on-going colonization. Today, colonization and related policies and processes, continue to manifest in the marginalization of Indigenous knowledge, particularly its use in research; however, Indigenous populations have moved from being research subjects to leaders and consumers of environmental health research. Given the tensions that exist between how health research is conducted, how the results are mobilized, and who has control and access to the results, we examine how peer-reviewed environment-related Indigenous health research in the Circumpolar North is serving the needs of Indigenous communities, governments, and organizations.

Methods

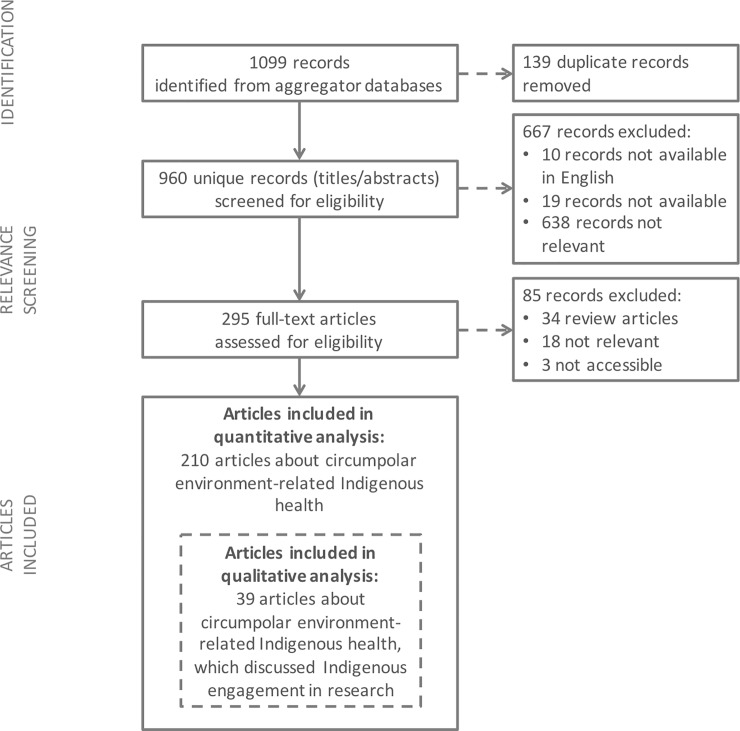

A modified systematic-realist literature review was conducted. Three databases were searched for peer-reviewed literature published from 2000 to 2015. Articles were included if the research focused on the intersection of the environment and health in Northern Canada and/or Alaska. A total of 960 unique records were screened for relevance, and 210 articles were analysed.

Results

Of these relevant articles, 19% discussed how Indigenous peoples were engaged in the research. There was a significant increase in reporting participatory, community-based methods over time; the proportion of articles reporting community-engagement varied by research topic; quantitative research articles were significantly less likely to report community-engaged methods; and most articles did not clearly report how the results were shared with the community.

Conclusion

The results raise a number of questions for the field of Circumpolar environment-related Indigenous health research, including whether or how authors of peer-reviewed literature should (or should not) be obliged to describe how research is serving Northern Indigenous communities. The results are intended to stimulate further conversations and bridge perceived dichotomies of quantitative/qualitative, Western/Indigenous, and empirical/community driven research approaches, as well as underlying assumptions that frame health research.

Introduction

Despite the heterogeneity of Indigenous cultures and communities across the Circumpolar North, there is often a shared experience of health inequities stemming from on-going colonization, including environmental displacement and dispossession, forced relocation, language and cultural erosion, and intergenerational trauma [1–12]. Inequities resulting from these socio-political realities include higher rates of infant mortality; infectious and chronic diseases; suicide; and lower life expectancies [6, 13, 14]. A challenge to those working in the health field—including policy makers, practitioners, community leaders, and frontline workers—is to understand and promote health within these socio-political contexts [9–11, 15].

Legacies of colonization manifest in the systemic marginalization of Indigenous knowledge, particularly its use in research [14, 16, 17]. For example, researchers have posited that the epistemological and praxiological divides between Indigenous knowledge and empirical positivist thought have manifested in research approaches [18–22]. In many cases, empirical approaches to health research are challenged to consider a holistic understanding of Indigenous health [19]. Indeed, metrics applied to measure Indigenous health often do not reflect Indigenous conceptualizations of health, as these metrics often originate in Western-informed reductionist research approaches. Such health research approaches may reify the objectification and marginalization of Indigenous knowledge contributions through the positioning of Indigenous knowledge as anecdotal, tokenistic, or unscientific, supporting the erasure of Indigenous knowledge from consideration [23–25]. Indeed, many Indigenous communities have expressed experiences of being ‘researched to death,’ positioned only as subjects of research, resulting in research that does not respond to local priorities, nor incorporate Indigenous ways of knowing [16, 21, 26–28].

Indigenous peoples worldwide, however, have not sat idly watching research define Indigenous health disparities; Indigenous groups and researchers are challenging Western-informed approaches to research [21, 24, 29]. Today, many Indigenous organizations are positioned to develop research projects through meaningful partnerships with researchers, universities, and/or institutes. Indeed, modern-day treaties have positioned Indigenous communities and governments to increasingly take control over the direction of Indigenous health research [21, 30, 31]. Still, tensions exist between how health research is conducted, how the results are mobilized, and who has control and access to the research results [17, 26, 32]. Additionally, research is often fraught with challenges that may act as barriers for Indigenous community-led health research, including: lack of funding to support community engagement in proposal development; timelines that do not allow for community engagement in research decision making processes; the frequent requirement that the principle investigator must be affiliated with a university; and tensions between qualitative and quantitative approaches [20, 29, 33, 34].

This literature review uses a systematic realist approach (defined below) to consider these challenges, and aims to understand how peer-reviewed environment-related Indigenous health research conducted in Northern Canada and the United States (Alaska) is serving the needs of Indigenous communities, governments and organizations. Specifically, we ask the following questions of literature focused on Northern environment-related Indigenous health:

Does Northern environment-related Indigenous health research speak to priorities communicated by Indigenous communities, governments, and organizations? How is this communicated in articles?

How can Indigenous communities, governments, and organizations access articles about environment-related health research conducted in the communities that they serve?

How do authors communicate the way in which the research results were used or applied by Indigenous communities, governments, or organizations?

We seek to stimulate conversations between and among health researchers, Circumpolar Indigenous communities, governments, health practitioners, and policy makers to identify methodologies that draw upon strengths from different research approaches; promote engagement with the communities, organizations, and governments; and respond to health and environment priorities of a changing North. While we examined research from the Circumpolar North, the findings, implications, and calls for future discussion apply to other Indigenous communities worldwide.

Materials and methods

This research was conducted through a systematic realist literature review approach (SRLR) [35–39]. Systematic literature reviews identify, screen, and synthesize large amounts of data through a transparent, comprehensive, and reproducible process [38]. A systematic realist literature review focuses on analyses of the underlying context of the literature, synthesis of data, and analysis of data by asking the who, what, why, and how questions of the literature [36, 40]. A realist review method considers the larger context of the concepts, constructs, motivations, and underlying theory that are shaping the research articles [36]. As such, a systematic realist literature review facilitates an analysis that is more explanatory in nature, discovers crosscutting themes across the literature to deepen understanding, strengthens critical analysis of the topics studied, and searches for common underlying mechanisms [35–37].

This SRLR drew upon methods outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), and drawing from concepts outlined in the PRISMA-Equity reporting guidelines to systematically search the literature and identify relevant articles, while the realist approach was used to analyze and synthesize the articles included for review [37, 38, 41, 42]. The realist approach was operationalised in this review by evaluating each article against community engagement criteria (see below) as a proxy for whom research was serving.

Search strategy

A search strategy aimed to identify English-language peer-reviewed articles published between January 1, 2000 and August 30, 2015 about research conducted in Northern Canada and Alaska (Fig 1), focusing on environment-related Indigenous health issues. In consultation with a health research librarian, a search string was developed (Table 1) and used to search PubMed, Web of Science, and CAB Direct. Records were uploaded into EndNote X7®, and de-duplicated.

Fig 1. Geographical focus of the systematic realist literature review: Northern Canada and Alaska, USA.

Table 1. The search terms used in three electronic bibliographic databases to identify articles for the systematic realist literature review on circumpolar environment-related Indigenous health research (2000–2015).

| Bibliographic Databases | Search String |

|---|---|

| PubMed | ((environment*) AND ((Circumpolar OR arctic OR Alaska OR “Northern Canada” Or Nunavut OR “Northwest Territories” OR Yukon OR Nunatsiavut OR Nunavik OR “Inuit Nunangat” OR Inuvialuit))) AND ((((Aboriginal OR indigenous OR “first nation*” OR Inuit* OR Inupiat* OR Eskimo* OR Aleut OR native OR Kalaallit OR Tlingit OR tsimshian OR haida OR Gwitchin OR Dene OR athabaskan* OR esquimaux))) OR (("Indians, North American"[Mesh]) OR "Inuits"[Mesh])) Filters: Publication date from 2000/01/01 to 2015/12/31; English |

| CAB Direct | ((Circumpolar OR arctic OR Alaska OR “Northern Canada” Or Nunavut OR “Northwest Territories” OR Yukon OR Nunatsiavut OR Nunavik OR “Inuit Nunangat” OR Inuvialuit) AND (Aboriginal OR indigenous OR “first nation*” OR Inuit* OR Inupiat* OR Eskimo* OR Aleut OR native OR Kalaallit OR Tlingit OR tsimshian OR haida OR Gwitchin OR Dene OR athabaskan* OR esquimaux) AND (health) AND la:(En OR English) AND yr:[2000 TO 2015]) NOT ((animal)) |

| Web of Science | (Circumpolar OR arctic OR Alaska OR “Northern Canada” Or Nunavut OR “Northwest Territories” OR Yukon OR Nunatsiavut OR Nunavik OR “Inuit Nunangat” OR Inuvialuit) AND TOPIC: (Aboriginal OR indigenous OR “first nation*” OR Inuit* OR Inupiat* OR Eskimo* OR Aleut OR native OR Kalaallit OR Tlingit OR tsimshian OR haida OR Gwitchin OR Dene OR athabaskan* OR esquimaux) AND TOPIC: (health) AND TOPIC: (environment) Timespan: 2000–2015. Search language = English |

Relevance screening and eligibility criteria

Relevance screening consisted of two steps. First, titles, abstracts, and keywords were screened for relevance. Relevant records proceeded to a second step, which involved screening the full-text of each article. In both steps, records were reviewed by two independent reviewers against inclusion/exclusion criteria that were developed a priori (Table 2). Reviewers met to discuss and resolve conflicts. All relevant full-text articles proceeded to data extraction and analysis.

Table 2. Summary of inclusion and exclusion criteria used to identify circumpolar environment-related Indigenous health literature (2000–2015).

| CRITERIA | LEVEL 1 SCREENING: Screening Titles and Abstracts | LEVEL 2 SCREENING: Screening the Full Text of Articles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical Criteria | • The study occurred only in Nunatsiavut, Nunavik, Nunavut, Inuvialuit, and/or Alaska (see Fig 1). | ✓ | ✓ |

| • The study did not include a non-circumpolar region (e.g. studies examining Canada would be excluded, even if Nunavut was covered in the study). | ✓ | ✓ | |

| • The study location was unclear. | ✓ | ||

| Human Health Criteria | • Any facet of human health and/or wellbeing was mentioned. | ✓ | ✓ |

| • A focus on human health was unclear. | ✓ | ||

| Population Criteria | • The study included Indigenous peoples. | ✓ | ✓ |

| • The study did not include non-Indigenous peoples. | ✓ | ✓ | |

| • The study population was unclear. | ✓ | ||

| Language and Date Criteria | • An English version of the title and/or abstract was available. | ✓ | ✓ |

| • The study was published during or after 2000. | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Study Design Criteria | • The article was a primary research study (e.g. a literature review, commentary, and non-research articles are excluded). | ✓ | |

| • The article was peer-reviewed. | ✓ |

Data extraction & analysis

Data were extracted from relevant articles (S1 Fig, S1 Table). Exact logistic regressions examined the effect of variables (i.e. year, location, research topic, methodologies) on the odds of articles reporting community-engaged approaches (i.e. Indigenous authorship, acknowledging Indigenous contributors, explicitly stating the use of participatory methods, obtaining permission by and participation from local organizations, and results-sharing frequencies and strategies).

Articles that described how Indigenous communities, governments, and/or organizations were engaged in the research process were thematically analysed. In the qualitative thematic analysis of the articles that described a community’s engagement with the research, indicators were developed based on the “4Rs” of Indigenous research—respect, relevance, reciprocity and responsibility—and the First Nations-developed research principles of ownership, control, access and possession (OCAP) [16]. Codes captured: community partners or organizations engagement in the research; initiation of research and by whom; limitations identified by the author(s) related to working with a community or region; research use by the community; and description of results mobilization within the community or with the partnering Indigenous organization. A “risk of bias” or other quality assessments were not conducted on individual studies because we were not assessing treatment effect or effect sizes; rather, we aimed to examine how articles reported environment and health literature serving Indigenous governments and organizations.

Results

Description of circumpolar environment-related Indigenous health literature

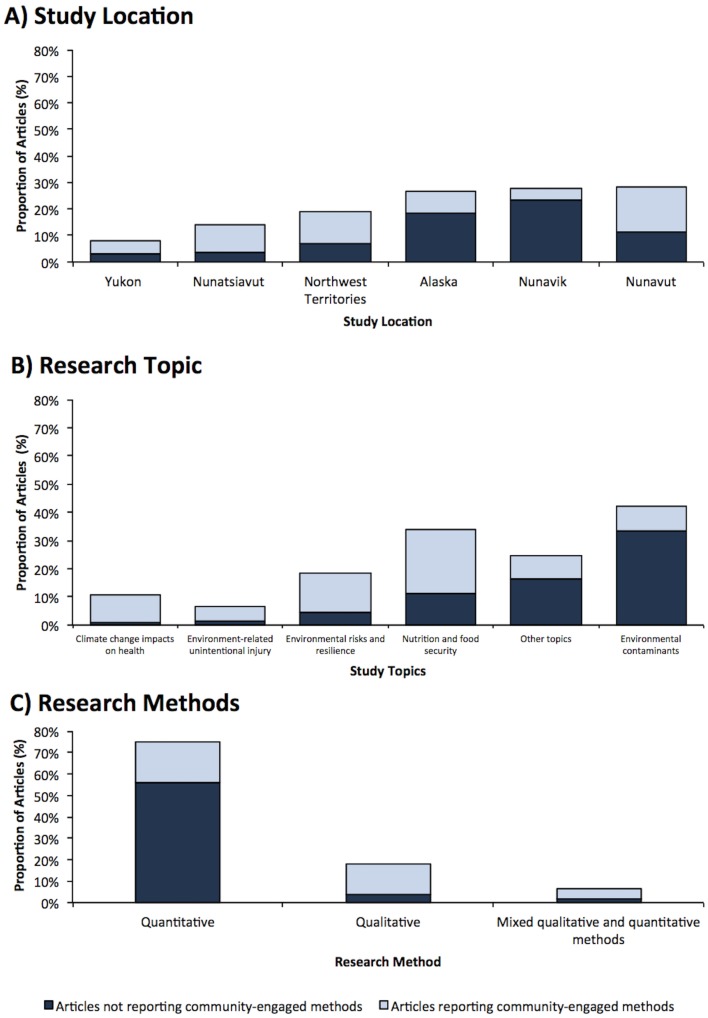

A total of 210 articles met the inclusion criteria (Fig 2). From these environment-related Indigenous health research articles (n = 210); the number of publications increased over time; most studies took place in Nunavut (28.1%), Nunavik (27.6%), and/or Alaska (26.7%); the most common topic was environmental contaminants (41.9%) and the majority of articles used quantitative research methods (75.2%) (Table 3). Community-engaged research was mentioned in 80 articles (38%).

Fig 2. Search strategy and results for the systematic realist literature review.

The inter-rater reliability for the screening was κ = 0.87, indicating “strong” agreement among the independent reviewers. [43].

Table 3. A summary of article attributes for all studies that examined health and environments in the Circumpolar North (2000–2015).

| Article Attributes | Total number of articles | Proportion of all health and environment articles (%) | Number of Articles Reporting Participatory Methods | Proportion of Articles Reporting Participatory Methods in the Category (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participatory, community-based, or other methods that engage the community in the study were used | 80 | 38.10% | ||

| Region* | ||||

| Nunavik | 58 | 27.60% | 9 | 15.52% |

| Nunavut | 59 | 28.10% | 35 | 59.32% |

| Northwest Territories | 40 | 19.00% | 25 | 62.50% |

| Nunatsiavut | 30 | 14.30% | 22 | 73.33% |

| Yukon | 17 | 8.10% | 10 | 58.82% |

| Alaska | 56 | 26.70% | 17 | 30.36% |

| Year of Publication | ||||

| 2000 | 3 | 1.40% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2001 | 5 | 2.40% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2002 | 4 | 1.90% | 2 | 50.00% |

| 2003 | 5 | 2.40% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2004 | 7 | 3.30% | 3 | 42.86% |

| 2005 | 8 | 3.80% | 2 | 25.00% |

| 2006 | 17 | 8.10% | 5 | 29.41% |

| 2007 | 9 | 4.30% | 6 | 66.67% |

| 2008 | 14 | 6.70% | 3 | 21.43% |

| 2009 | 12 | 5.70% | 4 | 33.33% |

| 2010 | 19 | 9.00% | 10 | 52.63% |

| 2011 | 24 | 11.40% | 11 | 45.83% |

| 2012 | 22 | 10.50% | 10 | 45.45% |

| 2013 | 24 | 11.40% | 7 | 29.17% |

| 2014 | 25 | 11.90% | 12 | 48.00% |

| 2015 | 12 | 5.70% | 5 | 41.67% |

| Topic* | ||||

| Environmental contaminants | 88 | 41.90% | 18 | 20.45% |

| Nutrition and food security | 71 | 33.80% | 47 | 66.20% |

| Environmental risks and resilience | 39 | 18.60% | 30 | 76.92% |

| Climate change impacts on health | 22 | 10.50% | 20 | 90.91% |

| Environment-related unintentional injury | 14 | 6.70% | 11 | 78.57% |

| Methods | ||||

| Quantitative | 158 | 75.20% | ||

| Qualitative | 38 | 18.10% | 30 | 78.95% |

| Qualitative and quantitative methods | 14 | 6.70% | 40 | 25.32% |

| Open-access articles | 100 | 47.60% | 50 | 50.00% |

| Indigenous organization(s) was/were listed as a co-author | 60 | 28.60% | 36 | 60.00% |

| Community members or governments were mentioned in the acknowledgment section | 142 | 67.60% | 68 | 47.89% |

| Permission from a local organization was explicitly reported | 106 | 50.50% | 66 | 62.26% |

| Article reported how the results were shared with the community | 31 | 14.80% | 29 | 93.55% |

*These categories are not mutually exclusive and therefore add up to more than 100%.

A total of 80 articles were screened for thematic analysis, after exclusions, 39 articles (18.6%) were reviewed for detailed descriptions of how Indigenous communities, governments, or organizations were engaged in the research (Fig 2).

Does published research speak to Northern priorities?

Articles reporting community-engagement varied by time, location, topic, and method

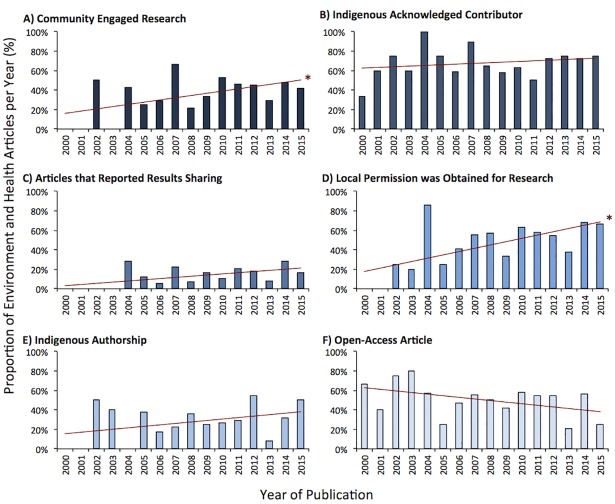

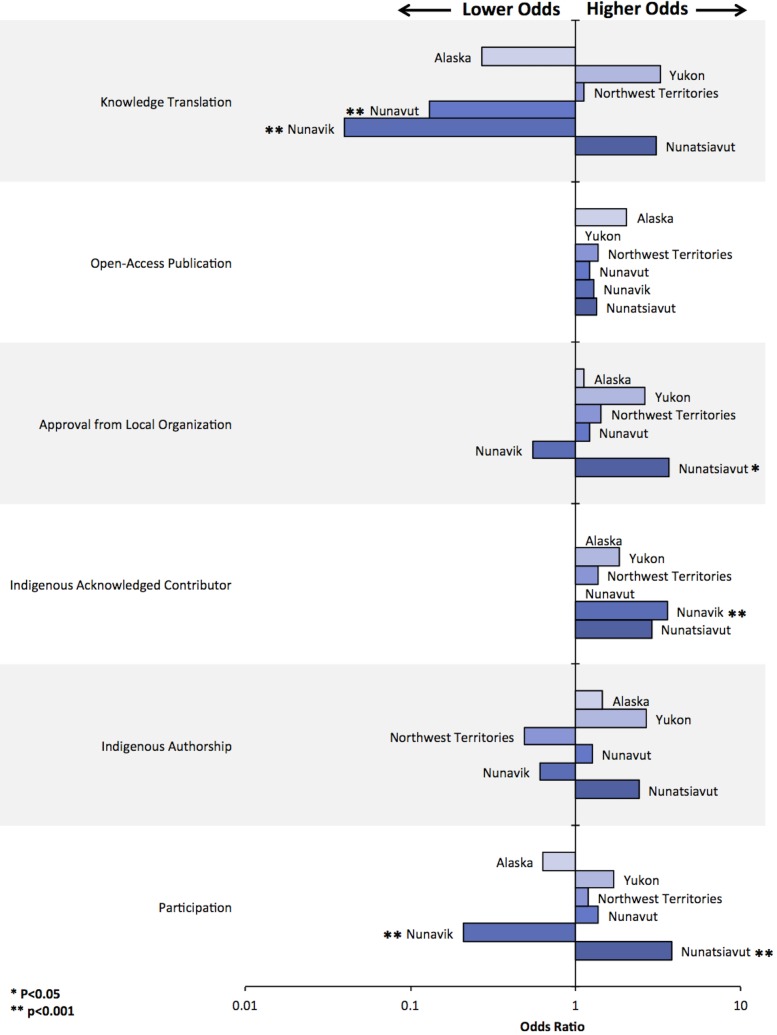

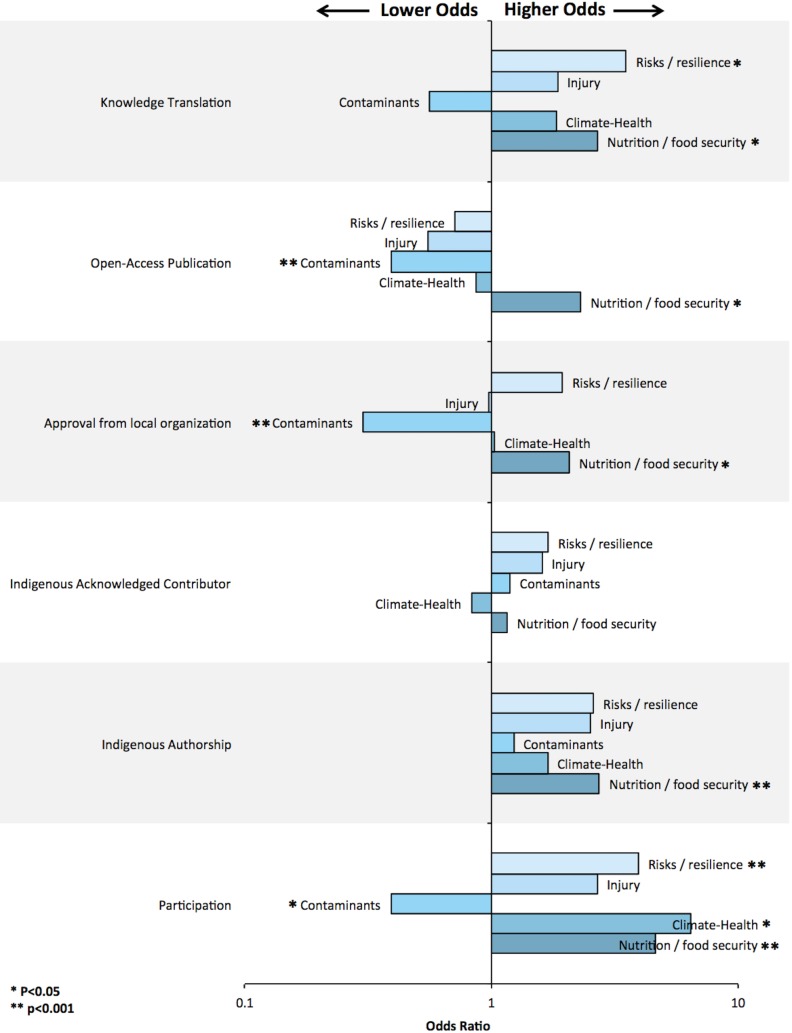

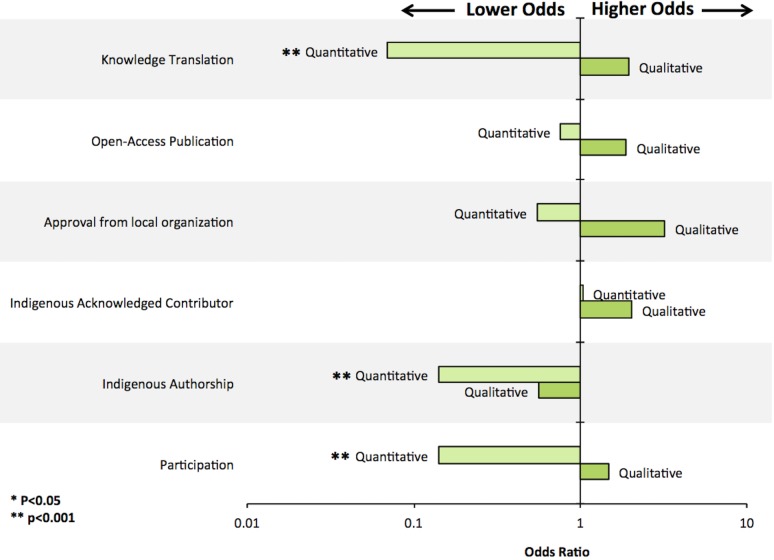

Of all the environment-related Indigenous health research articles (n = 210 articles), some publications mentioned using participatory, community-based research (CBPR) methods to engage the community in the study (38.1%) (Table 3). A modest, but statistically significant, increase in articles reporting CBPR methods was observed over time (Fig 3). Research conducted in Nunatsiavut was significantly more likely to report CBPR methods (p<0.05, Fig 4). While Nunavik had one of the highest number of environment-related Indigenous health research articles published, it was significantly less likely to report using CBPR methods (9/58 articles; 16%; p<0.05; Figs 4 and 5). Articles about nutrition and food security, climate change impacts on health, and environmental risks and resilience had significantly higher odds of reporting CBPR methods when compared to other topics (Figs 4 and 6; p<0.05). For example, while research about environmental contaminants was the most common research topic, it was significantly less likely to report CBPR methods compared to other topics (Figs 4 and 6; p<0.05). While quantitative methods were used in the large majority of health and environment articles (158/210 articles; 75%; Fig 4), they were significantly less likely to report using CPBR methods compared to qualitative research (40/158 articles; 25%; Fig 7; p<0.05).

Fig 3. Circumpolar health and environment article attributes that indicate some form of community involvement over time with a linear trend line.

Significant trends over time are marked with “*”.

Fig 4.

Proportion of circumpolar health and environment articles reporting community-engaged methods by (A) region, (B) research topic, and (C) research methods.

Fig 5. Multivariable exact logistic regression examining associations between location and various indicators of community-engaged research.

Fig 6. Multivariable exact logistic regression examining associations between research topic and various indicators of community-engaged research.

Fig 7. Multivariable exact logistic regression examining associations between research method and various indicators of community-engaged research.

Of the articles identifying the engagement of the community in the research (n = 39), information detailing how the regional or local Indigenous governing organization was involved, oversaw, or made aware of the research beyond citizens being research subjects was not consistently noted. If noted, this information was in the background to the research (n = 16/39) [44–58] the method section (n = 29/39) [47, 48, 50–52, 54, 55, 57, 59–79], and/or in the results section (n = 3/39) [59, 74, 80] of the articles. A number of diverse ways were employed to identify the role of the local or regional Indigenous governing organization in the research including the development of a research or advisory board [55, 65, 75, 77, 81]; identifying research as a ‘collaboration’ or ‘partnership’ with an Indigenous organization or government [44, 46, 48, 50, 51, 55, 56, 61, 62, 66, 73, 76, 79, 82]; and/or noting a workshop was hosted to engage or share information with the Indigenous government or organization [52, 62, 63]. Of the articles that detailed the role of community in the research, 33% (n = 13/39 articles) explicitly indicated that the research was community-initiated or community-led [46, 48, 51, 53, 55, 57, 60, 65, 67, 71, 80, 81, 83]. Community-initiated or -led was described as awarding the research funding to a local Indigenous government [53, 60], the principal investigator being the local Indigenous government [46], or a collaboration resulting from a previous working relationship between the academic researchers and the community [46, 51, 72].

Indigenous authorship was uncommon

Indigenous authorship on papers increased over time, with Nunatsiavut, Nunavut, Yukon, and Alaska having higher proportions of articles authored by Indigenous people, organizations, or governments; however, these differences were not statistically significant (p<0.05). Research reporting on nutrition and food security were significantly more likely to have Indigenous authorship compared to other topics (Fig 6; p<0.05), while research reporting the use of quantitative methods was significantly less likely to have Indigenous authorship compared to qualitative research (Fig 7; p<0.05).

Of the articles detailing the engagement of a community within the research (n = 39 articles), 74% (n = 29) listed a co-author with affiliation to an Indigenous community, government, or organization. Examples of author affiliation included: Indigenous governments [46, 47, 51–53, 55–57, 60, 65, 71–73, 75, 80, 83]; Indigenous focused health boards [48, 50, 58, 59, 64, 70]; community liaisons [44, 66, 76]; or an Indigenous-led research organization [51, 67, 68, 79]. In 10% (n = 4) of these articles, the name of the Indigenous organization that partnered in the research (and not an individual representing the Indigenous organization), was listed as the author [53, 56, 71, 83]. 77% (n = 30) of articles acknowledged the regional or local Indigenous government or organization in an acknowledgment section [47, 48, 51–53, 55, 56, 58, 60–66, 68–71, 73–76, 78–84]. Only one article (1/39 articles) did not include an Indigenous author affiliation or an Indigenous acknowledged contributor [49].

Community consent was inconsistently identified

Over time, there were modest but significant increases in reporting that Indigenous organizations granted permission to conduct research (Fig 3; p<0.05). Research conducted in Nunatsiavut was significantly more likely to report the granting of local permission to conduct research compared to other regions (Fig 5; p<0.05). While research on nutrition and food security were significantly more likely to report granting of local permission to conduct research, research on environmental contaminants was significantly less likely to report this permission compared to other research topics (Fig 6; p<0.05).

Of the articles that provided detailed information about engagement of a community in the research process, 56% (n = 22/39) explicitly described receiving research approval or permission from an Indigenous community, government or organization [44, 50, 51, 55, 57, 59–61, 63, 65–67, 69, 71–74, 76, 77, 80, 82, 83]. Additionally, 18% (n = 7/39 articles) did not clearly articulate the process of gaining permission by a local organization, but instead inferred community permission [46, 48, 53, 56, 68, 79, 81]. The descriptions of inferred permission varied and included: collaborating with an Indigenous government or community and/or working with a local advisory board [44, 46, 48, 50, 55, 56, 61, 65, 66, 71, 73, 75–77, 79, 81, 82]; a joint research-related intervention with an Indigenous organization [46, 53, 60, 65, 75, 80, 83]; a signed agreement with the community [56, 68, 77]; and/or articulating the role of the Indigenous government or organization in the title of article [46]. The descriptions of local permission were primarily reported in the article’s methods section, but also in an ethics section [63], a protocol section [78], and the background section [55, 79].

Were research results used by Indigenous communities, governments, or organizations?

Few articles reported on sharing the results with the community (n = 31/210 articles; 14.8%; Table 3); however, modest, but not significant, increases were observed over time (Fig 3; p>0.05). Research conducted in Nunavik, Nunavut, and Alaska were significantly less likely to report on knowledge mobilizations compared to other regions (Fig 5; p<0.05). Research on nutrition and food security as well as environmental risk and resilience were significantly more likely to report how results were shared compared to other research topics (Fig 6; p<0.05). Research using quantitative methods were significantly less likely to report how the research results were shared compared to qualitative research (Fig 7; p<0.05).

Of the articles that detailed the engagement of a community in the research, many describe the dissemination of results (66.7%, n = 26/39) [44, 46, 48, 50–53, 55–57, 60–62, 65–67, 71, 73, 75–77, 79–83]; however, there was no consistent method or section of the paper that this information commonly appeared. Examples of research mobilization include locally published booklets, reports, or DVDs [48, 50, 53, 75, 80]; and presentations to an Indigenous government [76].

Can Indigenous communities, governments, and organizations access research results?

A modest decrease in the number of open-access articles was observed over time (Fig 3; p>0.05). Nutrition and food security research was significantly more likely to be open-access; and research about environmental contaminants was significantly less likely to publish open-access articles compared to other research topics (Fig 6; p<0.05).

Of the articles that detailed community-engaged methods, the majority of articles (87%, n = 34/39) were accessible through some form of open-access [44, 46, 48–53, 55–60, 62, 63, 65–72, 75–84]. Of these open-access articles, 23% (n = 9/34) were published in the International Journal of Circumpolar Health [46, 48, 52, 62, 63, 68, 69, 76, 77]; 8% (n = 3/34) in EcoHealth [50, 53, 56]; 8% (n = 3/34) in Social Science and Medicine [55, 60, 71]; and 5% (n = 2/39) in Arctic [49, 75]. The remaining 50% (n = 17/34) of open-access articles were either published in another open-access journal or a journal that has an open-access option (n = 7/34) [59, 60, 65, 67, 70, 80, 81], or made publically available through a third party host (n = 10/34) [44, 50, 51, 57, 58, 66, 78, 79, 82, 84].

Discussion

Our findings suggest that reporting the relationship between researchers and Indigenous partners is not common practice in peer-reviewed environment-related health research in the Circumpolar North and, therefore, is not fully responding to a changing social and political climate in the North, which calls for the recognition of knowledge creation as a form of self-determination [17, 21]. This is an important consideration in challenging the legacies of on-going colonization. The creation of research as a form of self-determination is evident in the creation of self-governed territories, land claim settlement areas, and Indigenous health authorities, and has challenged the way in which decisions affecting the health of Indigenous peoples are identified and addressed [16, 85, 86]. As Indigenous communities are positioned to determine what research is required to support and promote the health of their populations, the role of the researcher and the research they produce is also changing. As reported in a number of articles in this SRLR, Indigenous governments and organizations are in the position to seek out the expertise to support their own research agendas [46, 48, 51, 53, 57, 60, 61, 67, 80, 81]; yet, few of these articles had Indigenous authorship.

While research may be responding to community-defined priorities, we found this is not frequently reported in peer-reviewed journal articles. In Canada, reporting on Indigenous leadership in defining the research is important given the recent national discourse on reconciliation and calls from Indigenous peoples to actively decolonize research and ensure that Indigenous needs, priorities, and ways of knowing are respected, responded to, and included [21, 87, 88]. A key question from this research then becomes: how do non-Indigenous researchers demonstrate their awareness of the changing socio-political environment and recognize the role of research in decolonization and reconciliation processes, and reflect and communicate this through peer-reviewed journal articles?

Of note, articles reporting CBPR methods increased over time. Tenets of CBPR are generally understood to align with Indigenous research ethics, which include developing a relationship with the community, attending to a process of mutual learning, and conducting research that responds to priorities identified by communities [21, 26, 32, 89]. However, the application and interpretation of such tenets vary among those using CBPR methodologies [17, 89]. We attempted to capture these variations, and analysed the degree of detail provided in the articles. For example, in one article, the authors outlined the engagement process and clearly indicated that the research was directed, overseen, and was important for the community [46]. A different approach in another article involved the authors stating that the research reflected the interests of an Indigenous government and was the outcome of an ongoing relationship [73]. These are two different approaches to identifying the role of the Indigenous governments in directing the research; however, both methods were published in a peer-review journals, identified the use of participatory or community engagement methods, and inferred knowledge, consent, and participation of the community. The reporting of this information helps clarify why the research was conducted, its relationship to the Indigenous community, and relevance for the community.

Quantitative research was less likely to report any metric of community engagement that we examined in this review. These findings suggest that quantitative research journals do not require, encourage, and/or reward reporting on these methodologies, and reflects quantitative health research not developing, or having been slow to develop, culturally safe guidelines or methods for active community participation [20]. It could further suggest that those working within this methodology are not fully considering or understanding knowledge creation as a process of reinforcing a colonial construct of health researchers as knowledge creators, and Indigenous peoples as subjects [21, 88, 90]. This is particularly germane for all health research, which is historically grounded in positivism and often considered neutral and value free, denying recognition that decisions made are imbued with underlying assumptions, which historically, are based in Western epistemologies and approaches [21, 33].

Given these realities, can it be expected that reporting community-engaged indicators could readdress the role of research in colonizing Indigenous peoples? It might be suggested that this is a contributing factor to actively work towards decolonizing health research. Indeed, outlining the role that Indigenous organizations played in the development of research shifts the gaze to where power is generated and held, and challenges the generation of knowledge as solely the domain of academic institutions [20, 21]. Further, Indigenous governments and organizations can benefit from research that utilizes quantitative and/or qualitative approaches. If this is generally understood and accepted, this research supports the position that a move towards detailed reporting of the role of Indigenous organizations and researchers should occur, regardless of research approach.

Also illuminated in our review is the lack of systematic or unifying method used to communicate how health research is responding to community-identified issues, and how the research has been used or applied by Indigenous communities. This absence could reflect the reality that describing and interpreting if and how a research project is indeed responding to community-identified issues is both difficult to achieve and discern. Furthermore, this can also be challenging given journal word count limits. Articles in this review, specifically those applying tenets of CBPR, provide insight into how researchers can better communicate if and how health research is responding to Indigenous-identified priorities. A number of indicators that communicated the relationship between the research project and the Indigenous government or organization were identified in this SRLR. Depending on the requirements of the journal, this information could be placed in the introduction, methods, or ethics approval section. In the discussion or conclusion of an article, alongside suggestions for future research ideas, acknowledgment of the way in which results were mobilized with the partnering Indigenous organizations may also communicate the relationship between research project and Indigenous communities.

Article authorship rarely included Indigenous authors [53, 56, 71, 83]. The practice of identifying the community, government, or organization as an author, as opposed to an individual representing a community, government or organization, avoids essentializing or silencing Indigenous participation in research. The practice, if acceptable to the community, government, or organization, is a challenge to recognizing authorship as defined by academic institutions. Consideration of the limitations of ‘recognition’ [87, 91, 92], then, may well provide the field of Circumpolar Indigenous health research further insight into who is defining Indigenous identity and how this shapes, upholds, challenges, or dismantles the distribution of power. Furthermore identifying a community, government, or organization as the author–while fraught with its own dilemmas about community and what constitutes community [89, 92],–ensures that the community is acknowledged as a contributor to the research.

This SRLR also explored how Indigenous governments or organizations are able to access research that has been conducted in the communities they serve, vis-à-vis some form of open-access. While the number of open-access articles was the only metric that decreased over time, what is not told through this metric is whether Northern Indigenous organizations are, indeed, accessing and using the peer-reviewed articles. We acknowledge that the ‘open access’ status of an article does not serve as an effective indicator of how the research was used by or served the involved community. This is not to suggest that current requirements and guidelines published by funding agencies requiring articles to be available within 12 months of publishing through open-access [93] is not a welcome move. Further research into this open-access query may illuminate the role of peer-review articles in informing Northern Indigenous directed policies and programs.

Finally, it is important to note that this literature review only assessed what authors wrote in their articles. We recognize that the absence of reporting community-engaged methods does not presume that the research did not genuinely engage with an Indigenous organization, respond to a community priority, work with an Indigenous organization to develop and/or implement the research project being reported. The absence of reporting community-engaged methods, for instance, could reflect journal word count limits, criteria for authorship, and other requirements imposed by academic journals. Indeed, this may bias what information gets published in peer-reviewed or grey literature.

Conclusion

We sought to determine if and how environment-related Indigenous health research conducted in the Circumpolar North communicates its role in serving communities in peer-reviewed journal articles. The small number of articles detailing community-engaged methods and the lack of unifying methods used to describe the relationship between the research project and the health research priorities of Indigenous governments or organizations give indication that reported health research is not keeping pace with a changing North. Notably, the predominance of qualitative research articles reporting community-engaged metrics could suggest that the importance of applying and reporting the tenets of CBPR is better understood among qualitative researchers than quantitative researchers. This could also suggest that CBPR approaches are better developed for qualitative research, and that methods that engage with the community and respond to community priorities needs to be further developed for quantitative health research.

Processes and impacts from the legacies of colonization endure to this day, and the demand for ethical health research that responds to community-defined and community-identified priorities is part of other growing movements across North America and, indeed, worldwide. The Idle No More movement, the hunger strike by Chief Theresa Spence of the Attawapiskat First Nation, the #MakeMuskratRight campaign, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Reports and related Calls to Action [94] are all movements by Indigenous leaders, communities, governments, and organizations that call for change in the relationship with Indigenous peoples. This call extends to those working in the area of health research; yet, how is this demonstrated to peers and those consuming peer review research?

Our findings concur with calls made for greater methodological transparency in peer reviewed literature involving Indigenous research participants or interests [17, 29]. To this end, we offer a number of indicators that should be reported in peer-reviewed articles to begin conveying to the reader the author’s knowledge of conducting ethical research with Indigenous communities and the manner in which the Indigenous community was engaged:

Recognize the Indigenous government or organization as an author;

Identify whether community permission to conduct the research was granted;

Describe the relationship of the Indigenous government or organization to the research project (i.e., initiator, principal investigator, collaborator);

Acknowledge the contributions of the advisory board; and/or

Identify and describe the role of the community in the article and abstract, and not solely in the acknowledgments section.

These indicators are not provided as a prescriptive or final check-list; rather, they serve to inspire a broader discourse on the issues of conducting health research with Indigenous populations. Considerations of how research is reported can contribute to de-essentializing Indigenous communities and raise awareness of how on-going colonization mediates Indigenous health status. Just as the methods used to address complex issues are diverse, so too are the people, findings, and application of the findings. Furthermore, there is no one way of approaching the health issues of the North, nor is it assumed there is one way of reporting on research conducted in the North. Engaging in an anti-colonial discourse, however, requires consideration of the role of reporting and what is reported in peer review journals. This requires the active participation of a number of players including health researchers of all methodologies, their students, the funders, the communities, and editorial boards of peer review journals.

Supporting information

(TIFF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The three authors of settler descent who live and work in the traditional territories of the Kwanlin Dun First Nation, Ta’an Kwach’an Council and the Little Salmon Carmacks First Nation, the ancestral lands of the Attawandaron people and the treaty lands and territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, and the homelands of the Innu and Inuit of Labrador, for a combined total of 50 years, wish to thank Mandy Nicholson, Steven Lam, Laura Banfield, Marie Puddister and the anonymous reviewers for their contributions. The authors acknowledge with gratitude funding provided by the Pierre Elliot Trudeau Foundation, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSRHC), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and the Canada Research Chairs Secretariat.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors acknowledge with gratitude funding provided by the Pierre Elliot Trudeau Foundation, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSRHC), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and the Canada Research Chairs Secretariat. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Willox AC, Stephenson E, Allen J, Bourque F, Drossos A, Elgarøy S, et al. Examining relationships between climate change and mental health in the Circumpolar North. Reg Environ Change. 2015;15(1):169–82. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tobias JK, Richmond CA. "That land means everything to us as Anishinaabe. …": Environmental dispossession and resilience on the North Shore of Lake Superior. Health Place. 2014;29:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.05.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Leeuw S, Maurice S, Holyk T, Greenwood M, Adam W. With Reserves: Colonial Geographies and First Nations Health. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2012;102(5):904–11. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2012.674897 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirmayer LJ, Fletcher C, Watt R. Locating the ecocentric self: Inuit concepts of mental health and illness Healing traditions: the mental health of Aboriginal peoples in Canada UBC Press, Vancouver: 2009:289–314. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richmond CAM, Ross NA. The determinants of First Nation and Inuit health: A critical population health approach. Health & Place. 2009;15(2):403–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waldram JB, Young TK, Herring A. Aboriginal Health in Canada: Historical, Cultural, and Epidemiological Perspectives. Toronto [Ont.]: University of Toronto Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hackett P. From past to present: understanding First Nations health patterns in a historical context. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005;96(Supplement 1):S17–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reading CL, Wien F. Health inequalities and the social determinants of Aboriginal peoples' health: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health Prince George, BC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czyzewski K. Colonialism as a broader social determinant of health. The International Indigenous Policy Journal. 2011;2(1):5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. The Lancet. 2009;374(9683):76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adelson N. The embodiment of inequity: health disparities in aboriginal Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005;96 Suppl 2:S45–61. Epub 2005/08/05. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young TK, Rawat R. Circumpolar health atlas: University of Toronto Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richmond CA. The social determinants of Inuit health: a focus on social support in the Canadian Arctic. International journal of circumpolar health. 2009;68(5):471–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnstone M-J. Research ethics, reconciliation, and strengthening the research relationship in Indigenous health domains: An Australian perspective. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2007;31(3):391–406. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Browne AJ. Discourses influencing nurses' perceptions of First Nations patients. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;37(4):62–87. Epub 2006/03/18. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castellano MB. Ethics of Aboriginal Research. International Journal of Indigenous Health. 2004;1(1):98. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ninomiya MEM, Pollock NJ. Reconciling community-based Indigenous research and academic practices: Knowing principles is not always enough. Social science & medicine. 2017;172:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal A. Dismantling the Divide Between Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge. Development and Change. 1995;26(3):413–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.1995.tb00560.x [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smylie J, Firestone M. Back to the basics: identifying and addressing underlying challenges in achieving high quality and relevant health statistics for indigenous populations in Canada. Statistical Journal of the IAOS. 2015;31(1):67–87. doi: 10.3233/SJI-150864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cameron M, Andersson N, McDowell I, Ledogar RJ. Culturally safe epidemiology: oxymoron or scientific imperative. Pimatisiwin. 2010;8(2):89 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith L. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. Second edition. ed. London New York: Zed Books; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler Walker J, Seddon L, McMullen E, Houseman J, Tofflemire K, Corriveau A, et al. Organochlorine levels in maternal and umbilical cord blood plasma in Arctic Canada. The Science of the total environment. 2003;302(1–3):27–52. Epub 2003/01/16. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovach ME. Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Neil J, Elias B, Wastesicoot J. Building a health research relationship between First Nations and the University in Manitoba. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2005;96(Supplement 1):S9–S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunsolo Willox A, Harper SL, Edge VL. Storytelling in a digital age: digital storytelling as an emerging narrative method for preserving and promoting indigenous oral wisdom Qualitative Research; 2012:1468794112446105. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bull JR. Research with Aboriginal Peoples: Authentic Relationships as a Precursor to Ethical Research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2010;5(4):13–22. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.4.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kowal E, Paradies Y. Ambivalent helpers and unhealthy choices: public health practitioners’ narratives of Indigenous ill-health. Social science & medicine. 2005;60(6):1347–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coombes B, Johnson JT, Howitt R. Indigenous geographies III: Methodological innovation and the unsettling of participatory research. Progress in Human Geography. 2014;38(6):845–54. doi: 10.1177/0309132513514723 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snijder M, Shakeshaft A, Wagemakers A, Stephens A, Calabria B. A systematic review of studies evaluating Australian indigenous community development projects: the extent of community participation, their methodological quality and their outcomes. BMC public health. 2015;15(1):1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schnarch B. Ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP) or self-determination applied to research. Journal of Aboriginal Health. 2004;1(1):80–95. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rigney L-I. Internationalization of an Indigenous anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies: A guide to Indigenist research methodology and its principles. Wicazo sa review. 1999;14(2):109–21. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ball J, Janyst P. Enacting Research Ethics in Partnerships with Indigenous Communities in Canada: “Do it in a Good Way”. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2008;3(2):33–51. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.2.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cochran PA, Marshall CA, Garcia-Downing C, Kendall E, Cook D, McCubbin L, et al. Indigenous ways of knowing: Implications for participatory research and community. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(1):22 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibson N, Lund C. Aligning expectations for funders and community researchers. Pimatisiwin—A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health. 2012;10(2):169–76. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review–a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of health services research & policy. 2005;10(suppl 1):21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirst M, O’Campo P. Realist review methods for complex health problems Rethinking Social Epidemiology: Springer; 2012. p. 231–45. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okoli C, Schabram K. A Guide to Conducting a Systematic Literature Review of Information Systems Research. Rochester: Social Science Research Network; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA StatementThe PRISMA Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenhalgh T, Wong G, Westhorp G, Pawson R. Protocol-realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: evolving standards (RAMESES). BMC medical research methodology. 2011;11(1):115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macaulay A, Jagosh J, Seller R, Henderson J, Cargo M, Greenhalgh T, et al. Assessing the benefits of participatory research: a rationale for a realist review. Global Health Promotion. 2011;18(2):45–8. doi: 10.1177/1757975910383936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Connor A, Anderson K, Goodell C, Sargeant J. Conducting Systematic Reviews of Intervention Questions I: Writing the Review Protocol, Formulating the Question and Searching the Literature. Zoonoses and public health. 2014;61(S1):28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Welch V, Petticrew M, Tugwell P, Moher D, O'Neill J, Waters E, et al. PRISMA-Equity 2012 extension: reporting guidelines for systematic reviews with a focus on health equity. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 2013;34(1):60–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia medica. 2012;22(3):276–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma S, Gittelsohn J, Rosol R, Beck L. Addressing the public health burden caused by the nutrition transition through the Healthy Foods North nutrition and lifestyle intervention programme. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics: the official journal of the British Dietetic Association. 2010;23 Suppl 1:120–7. Epub 2011/01/05. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01107.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furgal CM, Powell S, Myers H. Digesting the message about contaminants and country foods in the Canadian North: A review and recommendations for future research and action. Arctic. 2005;58(2):103–14. WOS:000230035900001. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wesche S, Schuster RC, Tobin P, Dickson C, Matthiessen D, Graupe S, et al. Community-based health research led by the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation. International journal of circumpolar health. 2011;70(4):396–406. Epub 2011/09/03. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chandler BA, Berger LR. The financial burden of injury-related hospitalizations to an Alaska Native health system. Alaska Med. 2002;44(2):30–4. Epub 2002/08/07. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Couture A, Levesque B, Dewailly E, Muckle G, Dery S, Proulx JF. Lead exposure in Nunavik: from research to action. International journal of circumpolar health. 2012;71:18591 Epub 2012/07/24. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18591 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3417507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tyrrell M. Making sense of contaminants: A case study of Arviat, Nunavut. Arctic. 2006;59(4):370–80. WOS:000242840400004. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flint CG, Robinson ES, Kellogg J, Ferguson G, Boufajreldin L, Dolan M, et al. Promoting wellness in Alaskan villages: integrating traditional knowledge and science of wild berries. EcoHealth. 2011;8(2):199–209. Epub 2011/09/15. doi: 10.1007/s10393-011-0707-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Douglas V, Chan HM, Wesche S, Dickson C, Kassi N, Netro L, et al. Reconciling traditional knowledge, food security, and climate change: experience from Old Crow, YT, Canada. Progress in community health partnerships: research, education, and action. 2014;8(1):21–7. Epub 2014/05/27. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2014.0007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fillion M, Laird B, Douglas V, Van Pelt L, Archie D, Chan HM. Development of a strategic plan for food security and safety in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Canada. International journal of circumpolar health. 2014;73:25091 Epub 2014/08/26. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v73.25091 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc4127828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harper SL, Edge VL, Cunsolo Willox A. ‘Changing Climate, Changing Health, Changing Stories’ Profile: Using an EcoHealth Approach to Explore Impacts of Climate Change on Inuit Health. EcoHealth. 2012;9(1):89–101. doi: 10.1007/s10393-012-0762-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gibson G, Klinck J. Canada’s resilient north: The impact of mining on aboriginal communities. Pimatisiwin. 2005;3(1):116–39. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Durkalec A, Furgal C, Skinner MW, Sheldon T. Climate change influences on environment as a determinant of Indigenous health: Relationships to place, sea ice, and health in an Inuit community. Social science & medicine. 2015;136–137:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parlee B, Berkes F, Teetl'it Gwich'in Renewable Resources C. Health of the land, health of the people: A case study on Gwich'in berry harvesting in northern Canada. EcoHealth. 2005;2(2):127–37. doi: 10.1007/s10393-005-3870-z. BIOSIS:PREV200510248856. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Organ J, Castleden H, Furgal C, Sheldon T, Hart C. Contemporary programs in support of traditional ways: Inuit perspectives on community freezers as a mechanism to alleviate pressures of wild food access in Nain, Nunatsiavut. Health Place. 2014;30:251–9. Epub 2014/12/03. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.09.012 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brubaker M, Berner J, Chavan R, Warren J. Climate change and health effects in Northwest Alaska. Global health action. 2011;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lanier AP, Redwood DG, Kelly JJ. The Alaska Education and Research Towards Health (EARTH) Study: cancer risk factors. Journal of cancer education: the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education. 2012;27(1 Suppl):S80–5. Epub 2012/02/03. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0333-4 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cunsolo Willox A, Harper SL, Ford JD, Edge VL, Landman K, Houle K, et al. Climate change and mental health: an exploratory case study from Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Climatic Change. 2013;121(2):255–70. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mead EL, Gittelsohn J, Roache C, Corriveau A, Sharma S. A community-based, environmental chronic disease prevention intervention to improve healthy eating psychosocial factors and behaviors in indigenous populations in the Canadian Arctic. Health education & behavior: the official publication of the Society for Public Health Education. 2013;40(5):592–602. Epub 2012/12/15. doi: 10.1177/1090198112467793 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peace DM, Myers E. Community-based Participatory Process—Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program for Northern First Nations and Inuit in Canada. International journal of circumpolar health. 2012;71 doi: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18412. WOS:000317107300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Friendship KA, Furgal CM. The role of Indigenous knowledge in environmental health risk management in Yukon, Canada. International journal of circumpolar health. 2012;71:19003 Epub 2012/08/08. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.19003 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3417550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Messier V, Levesque B, Proulx JF, Rochette L, Serhir B, Couillard M, et al. Seroprevalence of seven zoonotic infections in Nunavik, Quebec (Canada). Zoonoses and public health. 2012;59(2):107–17. Epub 2011/08/10. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2011.01424.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Racicot-Matta C, Wilcke M, Egeland GM. Development of radio dramas for health communication pilot intervention in Canadian Inuit communities. Health promotion international. 2014. Epub 2014/06/25. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau024 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pearce T, Smit B, Duerden F, Ford JD, Goose A, Kataoyak F. Inuit vulnerability and adaptive capacity to climate change in Ulukhaktok, Northwest Territories, Canada. Polar Record. 2010;46(2):157–77. doi: 10.1017/S0032247409008602 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bird SM, Wiles JL, Okalik L, Kilabuk J, Egeland GM. Living with diabetes on Baffin Island: Inuit storytellers share their experiences. Canadian journal of public health = Revue canadienne de sante publique. 2008;99(1):17–21. Epub 2008/04/26. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guyot M, Dickson C, Paci C, Furgal C, Chan HM. Local observations of climate change and impacts on traditional food security in two northern Aboriginal communities. International journal of circumpolar health. 2006;65(5):403–15. Epub 2007/02/27. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jones J, Nix NA, Snyder EH. Local perspectives of the ability of HIA stakeholder engagement to capture and reflect factors that impact Alaska Native health. International journal of circumpolar health. 2014;73:24411 doi: 10.3402/ijch.v73.24411 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4048592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fontaine J, Dewailly E, Benedetti JL, Pereg D, Ayotte P, Dery S. Re-evaluation of blood mercury, lead and cadmium concentrations in the Inuit population of Nunavik (Quebec): a cross-sectional study. Environmental health: a global access science source. 2008;7:25 Epub 2008/06/04. doi: 10.1186/1476-069x-7-25 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc2442064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harper SL, Edge VL, Ford J, Thomas MK, McEwen SA. Lived experience of acute gastrointestinal illness in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut: "Just suffer through it". Social science & medicine. 2015;126:86–98. Epub 2014/12/22. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mead E, Gittelsohn J, Kratzmann M, Roache C, Sharma S. Impact of the changing food environment on dietary practices of an Inuit population in Arctic Canada. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics: the official journal of the British Dietetic Association. 2010;23 Suppl 1:18–26. Epub 2011/01/05. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01102.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Durkalec A, Furgal C, Skinner MW, Sheldon T. Investigating Environmental Determinants of Injury and Trauma in the Canadian North. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014;11(2):1536–48. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110201536. PMC3945552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Giles AR, Castleden H, Baker AC. "We listen to our Elders. You live longer that way": Examining aquatic risk communication and water safety practices in Canada's North. Health & Place. 2010;16(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.05.007. WOS:000272790200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goldhar C, Bell T, Wolf J. Vulnerability to Freshwater Changes in the Inuit Settlement Region of Nunatsiavut, Labrador: A Case Study from Rigolet. Arctic. 2014;67(1):71–83. WOS:000334975400008. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Daley K, Castleden H, Jamieson R, Furgal C, Ell L. Municipal water quantities and health in Nunavut households: an exploratory case study in Coral Harbour, Nunavut, Canada. International journal of circumpolar health. 2014;73:1–10. Epub 2014/04/26. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v73.23843 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3970036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chan HM, Fediuk K, Hamilton S, Rostas L, Caughey A, Kuhnlein H, et al. Food security in Nunavut, Canada: barriers and recommendations. International journal of circumpolar health. 2006;65(5):416–31. Epub 2007/02/27. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Burger J, Gochfeld M. Changes in Aleut Concerns Following the Stakeholder‐Driven Amchitka Independent Science Assessment. Risk analysis. 2009;29(8):1156–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01191.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burger J, Gochfeld M, Pletnikoff K. Collaboration versus communication: The Department of Energy's Amchitka Island and the Aleut Community. Environmental Research. 2009;109(4):503–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2009.01.002. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gibson G, Martin J, Zoe JB, Edwards K, Gibson N. Setting our minds to it: community-centred research for health policy development in Northern Canada. Pimatisiwin—A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health. 2007;5(2):33–54. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM, Thomas L, Allen J, Hazel K, Hensel C. "Tied together like a woven hat:" Protective pathways to Alaska native sobriety. Harm reduction journal. 2004;1(1):10 Epub 2004/11/19. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-1-10 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc535345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sharma S. Assessing diet and lifestyle in the Canadian Arctic Inuit and Inuvialuit to inform a nutrition and physical activity intervention programme. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2010;23:5–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01093.x. WOS:000281636900003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cunsolo Willox A, Harper SL, Ford JD, Landman K, Houle K, Edge VL, et al. "From this place and of this place:" climate change, sense of place, and health in Nunatsiavut, Canada. Social science & medicine. 2012;75(3):538–47. Epub 2012/05/19. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.043 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Furgal C, Seguin J. Climate change, health, and vulnerability in Canadian northern Aboriginal communities. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(12):1964–70. Epub 2006/12/23. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8433 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc1764172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jeffery B, Abonyi S, Labonte R, Duncan K, Kanatami IT. Engaging Numbers. Journal of Aboriginal Health September. 2006:45. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tsey K, Lawson K, Kinchin I, Bainbridge R, McCalman J, Watkin F, et al. Evaluating research impact: the development of a research for impact tool. Frontiers in public health. 2016;4:160 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hunt S. Ontologies of Indigeneity: the politics of embodying a concept. Cultural Geographies. 2014;21(1):27–32. doi: 10.1177/1474474013500226 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wilson S. Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods: Fenwood Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Castleden H, Morgan VS, Lamb C. “I spent the first year drinking tea”: Exploring Canadian university researchers’ perspectives on community-based participatory research involving Indigenous peoples. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe canadien. 2012;56(2):160–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00432.x [Google Scholar]

- 90.Simpson LR. Dancing on our turtle's back: Stories of Nishnaabeg re-creation resurgence and new emergence. Winnipeg: ARP Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Coulthard GS. Red skin, white masks: Rejecting the colonial politics of recognition: JSTOR; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Alfred T, Corntassel J. Being Indigenous: Resurgences against contemporary colonialism. Government and Opposition. 2005;40(4):597–614. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Government of Canada. Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council 2015 [cited 2017 January 28].

- 94.Truth, Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIFF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.