Abstract

Objective

Healthcare and financial decision making among older persons has been previously associated with cognition, health and financial literacy, and risk aversion; however, the manner by which these resources support decision making remains unclear, as past studies have not systematically investigated the pathways linking these resources with decision making. In the current study, we use path analysis to examine the direct and indirect pathways linking age, education, cognition, literacy, and risk aversion with decision making. We also decomposed literacy into its subcomponents, conceptual knowledge and numeracy, in order to examine their associations with decision making.

Method

Participants were 937 community-based older adults without dementia from the Rush Memory and Aging Project who completed a battery of cognitive tests and assessments of healthcare and financial decision making, health and financial literacy, and risk aversion.

Results

Age and education exerted effects on decision making, but nearly two-thirds of their effects were indirect, working mostly through cognition and literacy. Cognition exerted a strong direct effect on decision making and a robust indirect effect working primarily through literacy. Literacy also exerted a powerful direct effect on decision making, as did its subcomponents, conceptual knowledge and numeracy. The direct effect of risk aversion was comparatively weak.

Conclusions

In addition to cognition, health and financial literacy emerged as independent and primary correlates of healthcare and financial decision making. These findings suggest specific actions that might be taken to optimize healthcare and financial decision making and, by extension, improve health and well-being in advanced age.

Keywords: decision making, health, finance, aging, education, cognition, health literacy, financial literacy, risk aversion

Introduction

Studies have reported variable findings regarding the relation of age with decision making across the adult lifespan; some have found that older age is associated with worse performance on decision making measures, whereas others have found the opposite or no association (Denburg, Tranel, & Bechara, 2005; Finucane, Mertz, Slovic, & Schmidt, 2005; Lamar & Resnick, 2004; Samanez-Larkin & Knutson, 2015). One conceptual formulation that might account for these variable findings holds that the association of age with decision making depends on the degree to which the decision at hand requires knowledge acquired throughout life versus basic cognitive skills (Li, Baldassi, Johnson, & Weber, 2013; Li et al., 2015). This formulation is based on the assumption that knowledge increases through mid-life and remains relatively static in old age, while basic cognitive skills decline during mid- and late-life. From this it follows that older age will confer an advantage when decisions emphasize knowledge but will confer a disadvantage when decisions emphasize cognition.

How this formulation plays out with respect to older adults’ decisions about healthcare and financial matters specifically is of special interest, as older adults are increasingly expected to navigate complex and evolving healthcare programs (e.g., Medicare and Medicare Part D), engage in shared decision making with medical providers, and actively manage retirement funds. Finucane and Gullion (2010) examined performance on a rigorously validated decision making tool that assesses the ability to comprehend and integrate healthcare and financial information and found that old-older adults (ages 75–97) performed worse than young-old adults (ages 65–74) who in turn performed worse than younger adults (ages 25–45). They also found that performance was independently associated with basic cognitive skills, general knowledge, and numeracy (i.e., the ability to utilize information that is quantitative, graphical, or probabilistic). However, because the contributions of these factors and their interrelations were not investigated within age groups, this study tells us relatively little about the correlates of healthcare and financial decision making during older adulthood specifically. This represents an important gap in knowledge because the development of decision making interventions for older adults hinges on our understanding of the factors that are associated with decision making during late-life.

In the current study, we present a model of healthcare and financial decision making that examines whether age is related to older adults’ performance on a measure of healthcare and financial decision making and, if so, determines whether age is associated with decision making directly or indirectly through specific decision making resources (Figure S1 in the online supplement). The decision making resources in our model included cognition and health and financial literacy, with the latter referring to ability to utilize domain-specific knowledge about health/healthcare and finances (Baker, 2006), in keeping with the conceptual formulation reviewed at the outset and our own work suggesting that cognition and literacy are independently associated with decision making in old age (Boyle, Yu, Wilson et al., 2012; James, Boyle, Bennett, & Bennett, 2012). It is worth emphasizing that domain-specific knowledge about health/healthcare and finances accumulates across much of adult lifespan, whereas literacy as traditionally defined refers to reading ability, which is established early in life. In addition, because healthcare and financial decisions often involve probabilistic outcomes and weighing potential benefits against potential losses, we added a measure of risk aversion to our model (Frydman & Camerer, 2016; Samanez-Larkin & Knutson, 2015; Tymula, Belmaker, Ruderman, Glimcher, & Levy, 2013); including risk aversion also is in keeping with a previous study in which we found that greater risk aversion is associated with poorer decision making above and beyond cognition among older adults (Boyle, Yu, Buchman, & Bennett, 2012). Beyond examining the relation of age with decision making, we sought to advance the existing literature by determining the degree to which education, an early-life factor, is directly or indirectly associated with healthcare and financial decision making and also by examining the degree to which cognition, literacy, and risk aversion are directly or indirectly associated with decision making.

To accomplish this, we leveraged data from a sample of more than 900 older adults without dementia and used path analysis to test the following specific hypotheses:

Age has a direct effect on decision making, such that older age is associated with poorer decision making; however, age also has indirect effects on decision making via cognition, literacy, and risk aversion.

Education has a direct effect on decision making but also has indirect effects through cognition, literacy, and risk aversion.

Cognition has a direct effect on decision making but also has indirect effects through literacy and risk aversion.

Literacy has a direct effect on decision making but also has an indirect effect through risk aversion (we based this hypothesis on the premise that individuals with better literacy – i.e., those who are more knowledgeable about health- and financial-related risk and its calculation – should be more apt at objectively quantifying risk and therefore make better decisions (Peters, Hart, Tusler, & Fraenkel, 2014)).

Risk aversion has a direct effect on decision making.

Finally, because health and financial literacy can be broken down into subcomponents pertaining to the utilization of conceptual knowledge and numeracy in healthcare and financial contexts (Donelle, Hoffman-Goetz, & Arocha, 2007; Peters, Hibbard, Slovic, & Dieckmann, 2007), and because numeracy was previously associated with performance on Finucane et al.’s decision making tool, we explored in a separate path analysis the direct and indirect effects of age, education, cognition, risk aversion, and literacy’s subcomponents – conceptual knowledge and numeracy – on decision making.

Method

Participants

Participants were Chicago metropolitans enrolled in the Rush Memory and Aging Project, an ongoing, longitudinal, clinical-pathologic study of aging and age-related diseases (Bennett, Schneider et al., 2012). Participants were recruited though a variety of locations and means, including senior housing facilities, retirement communities, subsidized housing, social service agencies, and church groups; this multipronged recruitment approach ensured good coverage across the socioeconomic spectrum. The Rush Memory and Aging Project and the substudy on decision making were each approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center. Informed consent was obtained from participants after a thorough presentation of the risks and benefits of study participation.

The Rush Memory and Aging Project started in 1997, and the substudy on decision making was started in 2010. When the present analyses were conducted, 1896 participants had completed the baseline evaluation; of those, 627 passed away, 78 withdrew prior to when the decision making assessment was added, and 70 had moved out of the geographical area or had severe sensory or comprehension difficulties that precluded them from completing the decision making assessment. This left 1121 potentially eligible participants, of which 49 were reluctant or refused the decision making assessment, 3 completed the decision making assessment with pending clinical diagnosis (due to a lag between when these participants completed the decision making assessment and when a diagnosis was rendered from their clinical evaluation), and 41 had yet to complete the decision making assessment. Of the remaining 1028 participants that had completed the decision making assessment, 52 were excluded due to the presence of dementia, and 39 had missing data. This left 937 participants available for the current analyses.

To determine whether the current sample differed from those who had missing data or refused the decision making assessment, we conducted analyses examining these two groups with respect to their demographics. We found that the two groups did not differ in terms of age, sex, or the percentage who were non-Hispanic white, although education was slightly higher among the current sample (p = .02).

Clinical Diagnosis

All participants in the Rush Memory and Aging Project undergo annual structured clinical evaluations (Bennett, Schneider et al., 2012). Dementia was diagnosed by clinicians experienced in the evaluation of older adults using the criteria of the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association, which require impairment in at least two cognitive domains and a history of cognitive decline (McKhann et al., 1984). Participants were not demented, and 20.3% (190 of 937) participants were diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Assessment of Healthcare and Financial Decision Making

Healthcare and financial decision making was assessed via a modified, 12-item version of a well-validated healthcare and financial decision making measure (Finucane et al., 2005; Finucane & Gullion, 2010). The modified version used in the current study consisted of a six-item healthcare module and a six-item financial module. The modules’ materials were designed to mimic real-world healthcare and financial decisions commonly encountered by older adults. Items were administered in person via structured interview, and answer choices were presented visually on show cards. In the healthcare and financial modules, participants were asked to view tables displaying information about HMO plans and mutual funds, respectively. The information in the tables was presented as numbers only or both numbers and value labels. Participants answered three simple items and three complex items for each module. All items required comprehension and integration of the information displayed in the tables; however, the complex items contained more information in the tables and more choices from which to select. For example, on a simple healthcare item, participants viewed a table displaying a number of characteristics for three HMO plans (e.g., member satisfaction, preventive care strategies, access to specialists, customer service, and premium costs) and were instructed to choose the HMO plan that is not below average on two of the characteristics. On a complex item, participants viewed a similar table with nine HMO plans and were instructed to choose the HMO that is not below average on four characteristics. Scores on the decision making assessment were the total number of items answered correctly (range = 0 – 12). The original healthcare and financial decision making measure has been shown to have adequate psychometric properties in terms of inter-rater reliability and short-term temporal stability (Finucane et al., 2005; Finucane & Gullion, 2010). In addition, the modified 12-item version used in this study had adequate internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s coefficient α = 0.78) and was previously associated with mortality among older adults without dementia (Boyle, Wilson, Buchman, & Bennett, 2013).

Assessment of Cognition

Cognition was assessed via a previously described battery of 21 individual performance-based tests (Bennett, Schneider et al., 2012). Cognitive tests were administered in person by a trained examiner. The Mini-Mental State Examination was used only for descriptive purposes, and Complex Ideational Material was used only for diagnostic classification purposes. The remaining 19 tests assessed five cognitive domains: episodic memory (seven tests: Word List Memory, Word List Recall, and Word List Recognition from the procedures established by the CERAD; immediate and delayed recall of Logical Memory Story A and the East Boston Story), semantic memory (three tests: Verbal Fluency, the Boston Naming Test, and the National Adult Reading Test), working memory (three tests: Digit Span forward and backward subtests from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised and Digit Ordering), perceptual speed (four tests: the oral version of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test, Number Comparison, Stroop Color Naming, and Stroop Word Reading), and visuospatial ability (two tests: Judgment of Line Orientation and Standard Progressive Matrices). Raw scores on each of the 19 tests were converted to z-scores based on the baseline mean and standard deviation of the entire cohort of the Rush Memory and Aging Project (of which the current sample is a subset). A composite measure of global cognition was calculated by averaging the z-scores of the 19 individual tests.

Assessment of Health and Financial Literacy

Health and financial literacy were assessed via a 32-item measure that was administered in person via structured interview and with answer choices presented visually on show cards (James et al., 2012). Health literacy was assessed via nine items that required understanding of health-related topics, such as Medicare and Medicare Part D, prescription instructions, treatment-associated risk, and common causes of mortality in older adults. Financial literacy was assessed via 23 items that required the execution of simple calculations (numeracy) and/or knowledge of financial concepts (e.g., compound interest, stocks, bonds); many of these items were designed to mimic items on the Health and Retirement Survey (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2007). Question format for all literacy items was true/false or multiple choice. Percent correct was calculated separately for health items and financial items. These two percentages were then averaged, yielding a score for total literacy (range = 0 – 100%). Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for total literacy was 0.75 in the current sample, suggesting adequate internal consistency. This same measure of total literacy also has been associated with health promoting behaviors and health status among older adults without dementia (Bennett, Boyle, James, & Bennett, 2012; Stewart et al., 2016). For the follow-up path analysis that decomposed literacy into knowledge and numeracy, we identified 19 knowledge-based items and 13 numeracy-based items and calculated percent correct for each.

Assessment of Risk Aversion

Risk aversion was measured via participants’ responses to a series of 10 questions used in standard behavioral economics methods (Barsky, Juster, Kimball, & Shapiro, 1997; Harrison & Elisabet Rutström, 2008). The examiner read aloud and presented on show cards the following scenario to participants: “Would you prefer $15 for sure, OR a coin toss in which you will get [an amount greater than $15] if you flip heads or nothing if you flip tails?” The potential reward for accepting the gamble ranged from $20.00 to $300.00, with the reward amount varying randomly across questions. When the potential reward associated with the gamble reaches $30.00, both the guaranteed payment and the gamble are equally profitable in the long run. However, when the gamble reward surpasses $30, the profitability of the gamble exceeds that of the guaranteed payment. Participant-specific risk aversion coefficients were derived using participants’ responses to these 10 questions, with higher scores indicating greater risk aversion (for information about the calculation of risk aversion, see Boyle, Yu, Buchman et al., 2012).

Demographics

Age was based on self-reported date of birth at the initial study evaluation and the date of the decision making assessment. Education (years of schooling) was based on self-report at the initial study evaluation.

Statistical Analysis

Path analysis was used to test the overall fit of our conceptual model and to test the hypothesized direct and indirect pathways linking age, education, cognition, literacy, and risk aversion with healthcare and financial decision making. The follow-up path analysis in which literacy was decomposed into knowledge and numeracy was identical to our initial path analysis except that we removed literacy and added paths linking age, education, and cognition to knowledge and numeracy and paths linking knowledge and numeracy to risk aversion and decision making. Associations among variables were calculated using the PROC CALIS procedure of SAS/STAT software, Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.). Five indices were used to assess overall model fit. Absolute model fit was assessed via the chi-square test statistic (χ2) and the standardized root mean square residuals (SRMSR) (adequate fit is indicated by a nonsignificant p-value for χ2 and a SRMSR value under 0.05). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), which penalizes models with a higher number of parameters, was examined as a way to further consider model parsimony (adequate fit is indicated by a RMSEA value under 0.05 and an upper bound of the 90% RMSEA Confidence Interval (CI) of less than 0.06) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Normed Fit Index (NFI) compared the fit of the hypothesized model against that of a baseline model assuming uncorrelatedness (adequate fit is indicated by a CFI and NFI greater than 0.95). Model fit was considered adequate only if all five of these indices were satisfied (i.e., nonsignificant p-value for χ2, both SRMSR and RMSEA < .05, and both CFI and NFI > 0.95). After establishing adequate model fit, standardized path loadings and the standardized total, direct, and indirect effects of age, education, cognition, and other resources on decision making were examined. To determine the degree to which a total effect worked indirectly through a specific individual resource (e.g., age → cognition → decision making), the standardized path loading linking one factor with an intermediary factor (e.g., age → cognition) was multiplied by standardized path loading linking the intermediary factor with decision making (e.g., cognition → decision making); this value was then divided by the total standardized effect (e.g., the total effect of age → decision making) and multiplied by 100, yielding the percentage of the total effect attributable to an indirect effect through the intermediary factor under investigation.

Results

Descriptive information about the sample is provided in Table 1. Mean percent correct on the healthcare and financial decision making measure was 64.9%. Intercorrelations between age, education, cognition, and other resources are displayed in Table S1 in the online supplement. In bivariate analyses, decision making was positively associated with education (r = 0.36, p < .001), cognition (r = 0.59, p < . 001), literacy (r = 0.60, p < . 001), conceptual knowledge, (r = 0.53 p < .001), and numeracy (r = 0.50, p < .001), and negatively associated with age (r = −0.32, p < . 001) and risk aversion (r = −0.23, p < . 001).

Table 1.

Descriptive information about the sample

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or percent |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 81.2 (7.59) |

| Female (%) | 76.4 |

| Education (years) | 15.4 (3.01) |

| Non-Hispanic white (%) | 91.0 |

| MMSE | 28.2 (1.76) |

| Decision making (total score) | 7.79 (2.73) |

| Cognition | 0.23 (0.52) |

| Literacy (% correct) | 68.4 (14.2) |

| Conceptual knowledge (% correct) | 65.3 (16.5) |

| Numeracy (% correct) | 79.1 (16.3) |

| Risk aversion | 0.38 (0.29) |

Note: SD = Standard deviation. Total score for decision making is the number of correct responses on the 12-item healthcare and financial decision making measure. Cognition is a composite score based on the average z scores of 19 tests. Risk aversion is calculated from responses on a 10-item risk aversion measure. Please see Methods for additional details.

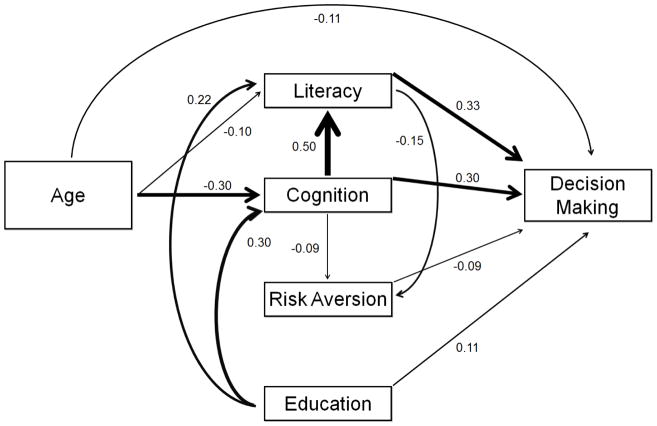

Initial screening of our decision making model revealed that the direct effects of age and education on risk aversion were not significant; therefore, we modified our conceptual model by removing the paths linking age and education to risk aversion. Path analysis indicated that this modified model provided adequate overall fit (χ2 = 2.810 [df = 2, p = 0.245], SRMSR = 0.011, RMSEA = 0.021, 90% CI [0, 0.072], CFI = 0.999, and NFI = 0.998). Parameter estimates for the hypothesized individual paths in the model were all significant (Figure 1). The total standardized effect of age on decision making was −0.284 (SE = 0.028, p < .001). Just over one-third of this total effect represented a direct effect of age on decision making (Est = −0.108, SE = 0.025, p < .001) (see Figure S2 in the online supplement for a scatterplot of the direct effect of age on decision making); the remainder was due to indirect effects (Est = −0.176, SE = 0.018, p < .001) via cognition and literacy (see Table S2 in the online supplement for partitioning of the total effects). Education behaved similarly to age in terms of the magnitude of its total effect (Est = 0.329, SE = 0.028, p < .001) and its approximately 1:2 ratio of direct to indirect effects (direct: Est = 0.113, SE = 0.026, p < .001; indirect: Est = 0.216, SE = 0.018, p < .001), with the latter running primarily through cognition and literacy. The total standardized effect of cognition on decision making was particularly strong (Est = 0.480, SE = 0.026, p < .001), and although two-thirds of this was direct (Est = 0.302, SE = 0.030, p < .001), the indirect effect, which worked primarily via literacy, was robust as well (Est = 0.178, SE = 0.018, p < .001). Literacy also exerted a powerful total effect on decision making (Est = 0.339, SE = 0.031, p < .001), the vast majority of which was direct (direct: Est = 0.326, SE = 0.031, p < .001; indirect: Est = 0.013, SE = 0.005, p = 0.01). By contrast, risk aversion’s direct effect on decision making was relatively weak (Est = −0.088, SE = 0.024, p < .001). Because these results might be influenced by the presence of older adults with MCI, we reran the path analysis including only those with no cognitive impairment (i.e., no MCI or dementia) and obtained very similar results, with the exception that the relatively weak association of cognition with risk aversion was no longer significant (Est = −0.056, SE = 0.044, p = .20) (Figure S3 in the online supplement). Also, to determine whether the current results were affected by the 39 participants with missing data (4% of the overall sample of 976 participants), we performed multiple imputation analysis on our primary path model. Missing data were imputed multiple times using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method (MCMC) (# of imputations = 25). Parameter estimates and associated standard errors from individual imputed datasets were then combined and analyzed for statistical inference. The results of this analysis were virtually identical to our original results (Table S3 in the online supplement).

Figure 1.

Path coefficients derived from path analysis

Note: Values represent standardized partial path coefficients, with the width of lines corresponding to the relative size of the coefficients.

The follow-up path analysis in which literacy was decomposed into conceptual knowledge and numeracy also provided adequate overall model fit (χ2 = 2.506 [df = 2, p = 0.286], SRMSR = 0.009, RMSEA = 0.016, 90% CI [0, 0.069], CFI = 1.000, and NFI = 0.998). We found a significant association of age with conceptual knowledge (Est = −0.122, SE = 0.028, p < .001) but not numeracy (Est = 0.012, SE = 0.030, p = .68), suggesting age worked through conceptual knowledge but not numeracy to affect decision making. On the other hand, education and cognition worked through both conceptual knowledge and numeracy to affect decision making (see Table S4 in the online supplement for partitioning of the total effects). In addition, both numeracy and conceptual knowledge worked through risk aversion to affect decision making, and conceptual knowledge and numeracy each exerted robust direct effects on decision making (Est = 0.191, SE = 0.030, p < .001 and Est = 0.206, SE = 0.028, p < .001, respectively).

Discussion

We used data from a cohort of more than 900 older adults without dementia to partition the complex interrelationships linking age, education, and diverse resources with performance on a well-validated measure of healthcare and financial decision making. Consistent with our hypotheses, age, education, and cognition each exerted direct and indirect effects on decision making in our path analysis, with cognition exerting a particularly strong overall effect as expected. Also consistent with our hypotheses, literacy and risk aversion each exerted direct effects on decision making; however, the direct effect of literacy was much stronger than that of risk aversion. A follow-up path analysis indicated that two subcomponents of literacy, conceptual knowledge and numeracy, each exerted robust direct effects on decision making. This study demonstrates that distinct but intertwined resources are associated with decision making both independently and through one another and suggests multiple targets for interventions that have the potential to optimize healthcare and financial decision making in advanced age.

Previous studies have examined the underpinnings of the association of age with healthcare and financial decision making across the entire adult lifespan (Finucane & Gullion, 2010; Li et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015); however, little is known about the resources that underlie this association among older adults specifically, and virtually no attention has been paid to the underpinnings of the association of education with decision making. Our path analysis directly addresses these issues, determining that nearly two-thirds of the overall association of age and education on decision making were due to indirect effects working through cognition and literacy. The indirect pathways linking older age with poorer decision making through lower cognition and lower literacy are consistent with evidence showing that both cognition and literacy decline during older adulthood (Kobayashi, Wardle, & von Wagner, 2015; Kobayashi, Wardle, Wolf, & von Wagner, 2015; Salthouse, 2012; Sperling et al., 2011; Yu, Wilson, Han et al., 2017). Our follow-up path analysis further demonstrated that the indirect effect of age through literacy was driven by conceptual knowledge but not numeracy. Whereas associations of age with numeracy have been inconsistently observed, previous studies have associated age with literary measures that emphasize conceptual knowledge (Donelle et al., 2007; Kobayashi, Wardle, Wolf, & von Wagner, 2016). These prior findings challenge the notion that domain-specific knowledge remains static or even increases during older adulthood, and the current study extends upon this by demonstrating that older age does not necessarily confer an advantage when decisions tap into knowledge bases. Notably, we recently reported that literacy declines with advancing age and that these declines predict incident mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s dementia (Yu, Wilson, Han et al., 2017). In addition, we recently reported that literacy among older adults without dementia is associated with the chief genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s dementia – the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele – and Alzheimer’s disease pathology, even after adjusting for cognition (Stewart et al., 2016; Yu, Wilson, Schneider, Bennett, & Boyle, 2017). Also related to these findings, we previously reported that lexical knowledge declines with advancing age and that these changes are associated with neuropathology (Wilson, Krueger, Boyle, & Bennett, 2011). These data, along with the recent recognition that the pathophysiological process of Alzheimer’s disease begins several years if not decades prior to its clinical manifestation (Sperling et al., 2011), raise the possibility that healthcare and financial conceptual knowledge declines as common neuropathologies gradually accumulate with age.

Regarding education’s indirect effects, the pathways associating lower education with poorer decision making through lower cognition and lower literacy are thought to at least partially reflect the life-long influence of education on cognition and literacy. However, education also is thought to increase neural reserve (Salthouse, 2012; Sperling et al., 2011; Stern, 2012), and as mentioned above, we recently associated lower literacy with Alzheimer’s disease pathology on postmortem examination (Yu, Wilson, Schneider et al., 2017). While additional research is needed to determine whether the association of literacy with subclinical neuropathology is moderated by education, it is possible that education might preserve decision making by buffering against neuropathology-related declines not only in cognition but also literacy. Contrary to our hypotheses, the indirect pathways linking age and education with decision making through risk aversion were nonsignificant. In hindsight, this was not entirely surprising given that, in our previous work, associations of age and education with risk aversion have not always persisted after adjusting for factors such as cognition (Boyle, Yu, Buchman et al., 2012; Boyle, Yu, Buchman, Laibson, & Bennett, 2011). The lack of a significant age-risk aversion association also is consistent with studies reporting nonsignificant or weak associations of age with measures of risk aversion that involve a gamble and with measures of health and financial risk-taking propensity (Josef et al., 2016; Mata, Josef, Samanez-Larkin, & Hertwig, 2011; Mamerow, Frey, & Mata, 2016). Lastly with regard to age and education, it is noteworthy that approximately one-third of their overall associations with decision making were direct, indicating that age and education are related to healthcare and financial decision making for reasons that are not yet fully understood.

The present study also advances our understanding of healthcare and financial decision making in old age by decomposing the associations of cognition and literacy. Cognitive ability is widely recognized as a fundamental element of decision making (Salthouse, 2012), and our measure of global cognition is robust in that it is comprised of 19 tests that assess various aspects of cognition, including the ability to attend to, comprehend, manipulate, and store information. Given this, it was not surprising that our model showed that decision making was closely tied to cognition. What was more surprising, however, was cognition and literacy had nearly equally strong independent associations with decision making. Our literacy measure requires the integration of general knowledge and computational abilities with domain-specific conceptual knowledge and numeracy (Chin et al., 2011; Peters et al., 2007), and because our cognitive battery directly assesses general knowledge and computational abilities, it seems likely that conceptual knowledge and numeracy are responsible for literacy’s robust unique effect on decision making. That conceptual knowledge and numeracy were uniquely associated with decision making in our follow-up path analysis further supports this interpretation and directly illustrates the importance of both accessing stored information about health and financial concepts and mentally manipulating health and financial information that is quantitative, graphical, or probabilistic in nature. Also noteworthy, approximately one-third of the overall association of cognition on decision making worked indirectly through conceptual knowledge and numeracy, which suggests that cognition supports healthcare and financial decision making not only by supplying general knowledge and computational abilities but also by facilitating the attainment and utilization of conceptual knowledge and numeracy skills prior to and during the decision making process.

The interrelated but largely independent associations of cognition and literacy with healthcare and financial decision making draw attention to several specific actions that might be taken to improve such decisions in advanced age. Some healthcare and financial programs, such as Medicare Part D (prescription drug benefit plan), have been critiqued by older adults as being overly complicated (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2006). The current results and work by others suggest that decision making might be improved by reducing cognitive demands through carefully designed informational aids that limit the number of options presented, display options in a logical fashion, and use visual cues to highlight critical information (Hanoch, Rice, Cummings, & Wood, 2009; Peters et al., 2007; Wood et al., 2011). However, along with reducing cognitive demands, our results suggest that health and financial literacy should be a primary target of interventions, as literacy’s independent association with decision making was among the strongest and accounted for approximately one-third of the overall association of cognition. Literacy might be targeted in interventions by limiting older adults’ reliance on conceptual knowledge and numeracy, for example, by defining health and financial terms and concepts upfront, reducing the need for calculations, and framing information such that higher numbers mean better performance (Peters et al., 2007). In addition to these extrinsic-based interventions, emerging evidence suggest that some aspects of literacy such as conceptual knowledge might be intrinsically modifiable, as the majority of older adults without dementia, including those with relatively weaker cognitive abilities, are without marked memory impairment and can learn new domain-specific knowledge, particularly when information is presented repeatedly (Brainard et al., 2016; Xie, 2011).

Risk aversion behaved somewhat differently than cognition and literacy in our path models in that it exerted a direct effect on decision making (such that greater risk aversion was independently associated with poorer decision making) but did not play a role in the associations of age and education with decision making and only played a minor role in the associations of cognition and literacy with decision making. Whereas the relatively weak indirect effects running through risk aversion are consistent with the notion that cognition and literacy contribute to decision making through the objective quantification of risk (Peters et al., 2014), risk aversion’s predominantly direct effect may suggest that it influences decision making via emotion-laden processes that are not otherwise represented in our model (e.g., comfort in accepting risk or minimizing or avoiding information that might provoke negative affect; see Carstensen, 2006). If borne out in subsequent research, this would indicate that decision making interventions should not only target cognition and literacy but also should address the emotional aspects of healthcare and financial decision making, for example, by increasing older adults’ awareness of risk-related negative affect and how this might lead to overly conservative (and therefore suboptimal) decisions.

As a final note on interventions, it is worth emphasizing that the aforementioned extrinsic-based interventions (i.e., reducing cognitive and literacy demands) and intrinsic-based interventions (i.e., bolstering conceptual knowledge about health/healthcare and finances and increasing awareness of risk-related negative affect) aim to make healthcare and financial decisions less daunting and underscore the self-relevance/importance of such decisions. This is crucial because it addresses an important motivational aspect of decision making. Making decisions less difficult and clarifying their relevance to the decision maker promotes the perception that good decision making is possible and worthwhile, and this should help ensure that older adults remain motivated to put forth the extra effort needed to attenuate disadvantages related to age, education, or other decision making resources, including any tendency to minimize or avoid information that might provoke negative affect (e.g., risk) (Hess, Queen, & Ennis, 2012; Hess, Smith, & Sharifian, 2016; Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2007). Motivational interviewing, a method by which providers help individuals systematically explore both the positive and negative ramifications of different choices, might be particularly relevant in this regard, as this technique not only drives home the importance of decisions but also would help older adults overcome any bias towards positive information.

This study has strengths and limitations. Its strengths include a well-characterized sample of more than 900 community-based older adults without dementia, a decision making measure that mimics real-world healthcare and financial decisions and has been shown to predict mortality in old age (Boyle, Wilson et al., 2013), and the use of path analysis, which allowed us to precisely quantify the direct and indirect associations of a diverse set of resources with decision making. We also replicated our core findings after restricting our sample to older adults with no cognitive impairment (i.e., no MCI or dementia). One limitation is that our sample consisted mainly of non-Hispanic white participants, and although level of education varied considerably, our overall sample was relatively highly educated. We are collecting decision making data among older African Americans and will examine the degree to which the current findings generalize to more diverse samples in future research. Another limitation is this study’s cross-sectional design. Longitudinal data collection of our measures of decision making, cognition, literacy, and risk aversion is ongoing, and we will be able to investigate the role of intraindividual change in these measures once we have collected sufficient data. A final limitation noted here is our use of a single decision making measure. While our decision making measure is well-constructed, the degree to which performance translates to the wide variety of healthcare and financial decisions faced in old age is not known. Future research should incorporate other measures of healthcare and financial decision making, including real-world proxies such as credit scores (Li et al., 2015), as these might show different associations with age and relevant decision making resources. A similar caveat is that measures of health and financial literacy and risk aversion vary considerably. For example, Bonem, Ellsworth, & Gonzalez (2015) found that older adults are particularly risk averse in health-related contexts, and the lack of a health component or actual payoffs in our measure of risk aversion might have attenuated its effect on decision making. Thus, careful consideration of the design and demands of specific measures is important when considering generalization of the current results. Despite these challenges, continued investigation in this area has the potential to shed light on some of the earliest neurobehavioral changes in aging and will aid in the development of tailored decision making interventions that promote independence and well-being in advanced age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements and Funding

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the thousands of Illinois residents who have participated in the Rush Memory and Aging Project and to the staff of the Rush Memory and Aging Project and the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, without which this work would not be possible.

This study was supported by NIA Grants R01AG17917 (Bennett), R21AG30765 (Bennett), R01AG34374 (Boyle), and R01AG33678 (Boyle). None of the authors have any financial conflicts of interest to disclose in relation to this article.

References

- Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:878–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsky B, Juster FT, Kimball M, Shapiro M. Preference parameters and behavioral heterogeneity: An experimental approach in the health and retirement study. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1997;112:537–579. doi: 10.1162/003355397555280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett JS, Boyle PA, James BD, Bennett DA. Correlates of health and financial literacy in older adults without dementia. BMC Geriatrics. 2012;12:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the Rush Memory and Aging project. Current Alzheimer Research. 2012;9:646–663. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonem EM, Ellsworth PC, Gonzalez R. Age differences in risk: Perceptions, intentions and domains. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2015;28(4):317–330. doi: 10.1002/bdm.1848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Yu L, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Poor decision making is associated with an increased risk of mortality among community-dwelling older persons without dementia. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;40(4):247–252. doi: 10.1159/000342781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle P, Yu L, Buchman A, Bennett D. Risk aversion is associated with decision making among community-based older persons. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3:205. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Yu L, Buchman AS, Laibson DI, Bennett DA. Cognitive function is associated with risk aversion in community-based older persons. BMC Geriatrics. 2011;11(1):53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Yu L, Wilson RS, Gamble K, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Poor decision making is a consequence of cognitive decline among older persons without Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment. PloS One. 2012;7(8):e43647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard J, Loke Y, Salter C, Koos T, Csizmadia P, Makai A … Irohla Consortium. Healthy ageing in Europe: Prioritizing interventions to improve health literacy. BMC Research Notes. 2016;9:270-016-2056-9. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2056-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science. 2006;312(5782):1913–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.1127488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J, Morrow DG, Stine-Morrow EAL, Conner-Garcia T, Graumlich JF, Murray MD. The process-knowledge model of health literacy: Evidence from a componential analysis of two commonly used measures. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16:222–241. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denburg NL, Tranel D, Bechara A. The ability to decide advantageously declines prematurely in some normal older persons. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43(7):1099–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelle L, Hoffman-Goetz L, Arocha JF. Assessing health numeracy among community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Health Communication. 2007;12(7):651–65. doi: 10.1080/10810730701619919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane ML, Gullion CM. Developing a tool for measuring the decision-making competence of older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25(2):271–288. doi: 10.1037/a0019106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane ML, Mertz CK, Slovic P, Schmidt ES. Task complexity and older adults’ decision-making competence. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20(1):71–84. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman C, Camerer CF. The psychology and neuroscience of financial decision making. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2016;20(9):661–675. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanoch Y, Rice T, Cummings J, Wood S. How much choice is too much?: The case of the Medicare Drug Benefit. Health Services Research. 2009;44:1157–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00981.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison GW, Elisabet Rutström E. Risk Aversion in Experiments. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2008. Risk aversion in the laboratory; pp. 41–196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Queen TL, Ennis GE. Age and self-relevance effects on information search during decision making. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2013;68(5):703–711. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Smith BT, Sharifian N. Aging and effort expenditure: The impact of subjective perceptions of task demands. Psychology and Aging. 2016;31(7):653–660. doi: 10.1037/pag0000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James BD, Boyle PA, Bennett JS, Bennett DA. The impact of health and financial literacy on decision making in community-based older adults. Gerontology. 2012;58:531–539. doi: 10.1159/000339094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josef AK, Richter D, Samanez-Larkin GR, Wagner GG, Hertwig R, Mata R. Stability and change in risk-taking propensity across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2016;111(3):430–450. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Selected findings on seniors’ views of the Medicare prescription drug benefit. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/7463.cfm.

- Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, von Wagner C. Internet use, social engagement and health literacy decline during ageing in a longitudinal cohort of older English adults. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2015;69(3):278–283. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, Wolf MS, von Wagner C. Cognitive function and health literacy decline in a cohort of aging English adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2015;30(7):958–964. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3206-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, Wolf MS, von Wagner C. Aging and functional health literacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2016;71(3):445–57. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamar M, Resnick SM. Aging and prefrontal functions: Dissociating orbitofrontal and dorsolateral abilities. Neurobiology of Aging. 2004;25(4):553–558. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Baldassi M, Johnson EJ, Weber EU. Complementary cognitive capabilities, economic decision making, and aging. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28(3):595–613. doi: 10.1037/a0034172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gao J, Zeynep Enkavi A, Zaval L, Weber EU, Johnson EJ. Sound credit scores and financial decisions despite cognitive aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112(1):65–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockenhoff CE, Carstensen LL. Aging, emotion, and health-related decision strategies: Motivational manipulations can reduce age differences. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22(1):134–146. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi A, Mitchell OS. Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: Evidence and implications for financial education. Business Economics. 2007;42:35–44. doi: 10.2145/20070104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mamerow L, Frey R, Mata R. Risk taking across the life span: A comparison of self-report and behavioral measures of risk taking. Psychology and Aging. 2016;31(7):711–723. doi: 10.1037/pag0000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata R, Josef AK, Samanez-Larkin GR, Hertwig R. Age differences in risky choice: A meta-analysis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1235:18–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters E, Hibbard J, Slovic P, Dieckmann N. Numeracy skill and the communication, comprehension, and use of risk-benefit information. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2007;26(3):741–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters E, Hart PS, Tusler M, Fraenkel L. Numbers matter to informed patient choices: A randomized design across age and numeracy levels. Medical Decision Making. 2014;34(4):430–42. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13511705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. Consequences of age-related cognitive declines. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012;63:201–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanez-Larkin GR, Knutson B. Decision making in the ageing brain: Changes in affective and motivational circuits. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2015;16(5):278–289. doi: 10.1038/nrn3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, … Park DC. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7(3):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2012;11(11):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CC, Boyle PA, James BD, Yu L, Han SD, Bennett DA. Associations of APOE ε4 with health and financial literacy among community-based older adults without dementia. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2016:gbw054. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tymula A, Belmaker LAR, Ruderman L, Glimcher PW, Levy I. Like cognitive function, decision making across the life span shows profound age-related changes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110(42):17143–17148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309909110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Boyle PA, Bennett DA. Loss of basic lexical knowledge in old age. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2011;82(4):369–72. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.212589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood S, Hanoch Y, Barnes A, Liu PJ, Cummings J, Bhattacharya C, Rice T. Numeracy and Medicare Part D: The importance of choice and literacy for numbers in optimizing decision making for Medicare’s prescription drug program. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(2):295. doi: 10.1037/a0022028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B. Effects of an eHealth literacy intervention for older adults. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011;13(4):e90. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Wilson RS, Han SD, Leurgans S, Bennett DA, Boyle PA. Decline in literacy and incident AD dementia among community-dwelling older persons. Journal of Aging and Health. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0898264317716361. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Boyle PA. Financial and health literacy predict incident Alzheimer’s disease dementia and pathology. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2017;56(4):1485–1493. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.