Abstract

Obtaining detailed individual-level data on both exposure and cancer outcomes is challenging, and it is difficult to understand and characterize how temporal aspects of exposures translate into cancer risk. We show that, in lieu of individual-level information, population-level data on cancer incidence and etiological agent prevalence can be leveraged to investigate cancer mechanisms and better characterize and predict cancer trends. We use mechanistic carcinogenesis models (multistage clonal expansion (MSCE) models) and data on smoking, H. pylori, and HPV infection prevalence to investigate trends of lung, gastric, and HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers. MSCE models are based on the initiation-promotion-malignant-conversion paradigm and allow for interpretation of trends in terms of general biological mechanisms. We assumed the rates of initiation depend on the prevalence of the corresponding risk factors. We performed two types of analysis: using the agent prevalence and cancer incidence data to estimate the model parameters and using cancer incidence data to infer the etiological agent prevalence as well as the model parameters. By including risk factor prevalence, MSCE models with as few as three parameters closely reproduced forty years of age-specific cancer incidence data. We recovered trends of H. pylori prevalence in the U.S. and demonstrated that cohort effects can explain the observed bimodal, age-specific pattern of oral HPV prevalence in men. Our results demonstrate the potential for joint analyses of population-level cancer and risk factor data through mechanistic modeling. This approach can be a first step in systematically testing relationships between exposures and cancer risk when individual-level data is lacking.

Keywords: multistage clonal expansion model, gastric cancer, lung cancer, oropharyngeal cancer, SEER cancer registry

Introduction

Risk factors for cancer can be difficult to assess because of the long time that it takes for cancer to develop and the long lag time between exposures to etiological agents and cancer onset and detection. It is even more challenging to further characterize how different temporal patterns of exposure translate into age-specific cancer risk. For instance, how does the risk associated with an exposure at one age compare to that for the same exposure at a different age? Or, how does risk compare for two people with the same cumulative exposures but very different temporal distributions of that exposure? For most risk factors, especially those whose association or causal relation with cancer are not well established, the answers to these questions are usually unknown, with very limited individual data available to study these issues. We must then resort to analyses of population-level data of cancer incidence and risk factor prevalence as a first step to study the temporal relationship between exposures and cancer risk.

Modeling the connection between population-level prevalence of etiological agents and population-level incidence of cancer is particularly challenging because of the multiple spatial and temporal scales involved (e.g., from cell level to population level and exposure timescale to carcinogenesis timescale). In particular, time of exposure, duration of exposure, dependence on age, and the dose–response relationship may all impact the risk of cancer onset and progression. Multistage clonal expansion (MSCE) models are a family of mechanistic models that provide a framework to integrate time-varying exposures into the analysis of cancer epidemiological data. The initiation–promotion–malignant-conversion hypothesis [1, 2] posits that cancer is the accumulation of rare events, nominally mutations; after accumulating a sufficient number of mutations (initiation), the tumor expands clonally (promotion), and a final mutation transforms a cell to malignancy (malignant conversion). Based on this framework, MSCE models seek to explain cancer incidence patterns in terms of the modeled, underlying biological carcinogenesis mechanism. Several studies have leveraged MSCE models to look at time-varying exposures in prospective individual-level data (e.g., of radiation, smoking, and benzene exposure) [3–5]. One recent study has used an MSCE model to connect population-level risk factor data to cancer-incidence: Hazelton et al. [6] investigated the connection between prevalence of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (sGERD) to incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). Estimation of model parameter values from cancer incidence data has been a focus of MSCE research both because parameter estimates are necessary for cancer incidence rate prediction and the evaluation of interventions such as screening (e.g., [7, 8]) and because they can help explain the underlying mechanistic reasons for health disparities (e.g., [9–12]).

To show the potential of combining population-level risk factor and cancer data through mechanistic modeling, we consider two kinds of time-varying cancer risk factors for which data at the population level is sometimes available: infectious agents and tobacco use. Approximately 15–20% of cancer deaths worldwide are attributed to infectious agents, including the human papillomavirus (HPV), Helicobacter pylori, hepatitis B and C viruses, Epstein–Barr viruses, Kaposi sarcoma herpes virus, and liver flukes (Opisthorchis viverrini), among others [13]. Some infectious agents, particularly viruses, can cause cancer through direct destabilization of normal cell controls, while other agents cause chronic inflammation or suppress the immune system in ways that can indirectly lead to carcinogenesis [14]. Another 25–30% of cancer deaths can be attributed to tobacco use [13]; although known to be the etiological agent of most lung cancers, tobacco use is also a risk factor for many other cancers (liver, head & neck, and colorectal cancer in particular [15]).

In this paper, we investigate how much can be learned by coupling population-level risk factor prevalence data to cancer incidence data through mechanistic modeling of carcinogenesis and statistical analyses of cancer trends. In particular, we evaluate whether the use of risk factor data improves the estimation and inference of mechanistic model cancer parameters that represent the rates of cancer initiation, promotion, and malignant conversion. By assuming that the tumor initiation rate depends on the risk factor prevalence, we connect population-level data on the etiological agent prevalence to population-level data on cancer incidence in three case studies: H. pylori and intestinal-type noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma (GAC), smoking and malignant neoplasms of the bronchus and lung (LC), and HPV and HPV-related oral (oropharyngeal and oral cavity) squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). We not only use prevalence data to inform models of cancer incidence but determine whether cancer incidence can help us to estimate historic agent prevalence patterns.

Methods

Data

Cancer incidence

We consider cancers reported to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registries [16], using SEER 9 data from 1973–2014. We use the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and histological subtype codes to identify cases of GAC (C16.1–16.6, C16.8–16.9 of type M8010, M8140, M8211, or M8144), HPV-related OSCC (C01.9, C02.4, C09.0, C09.1, C09.8–09.9, C10.0–10.4, C10.8, C10.9, C14.2), and LC (C34).

Risk factor prevalence

Yeh et al. [17] reported cohort prevalence of H. Pylori at age 20 for men in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [18] (specifically in NHANES III and Continuous NHANES); we smooth this data using natural splines. Smoking prevalence in the U.S. by cohort was estimated using the data generated by Holford et al. [19] and available here [20]. Age-specific cervicogenital prevalence of HPV was previously reported in Brouwer et al. [21]. Prevalences of H. pylori, smoking, and cervicogenital HPV are shown in the supplementary material (Figure S1a–d).

Mechanistic models

MSCE models with population-level risk factors

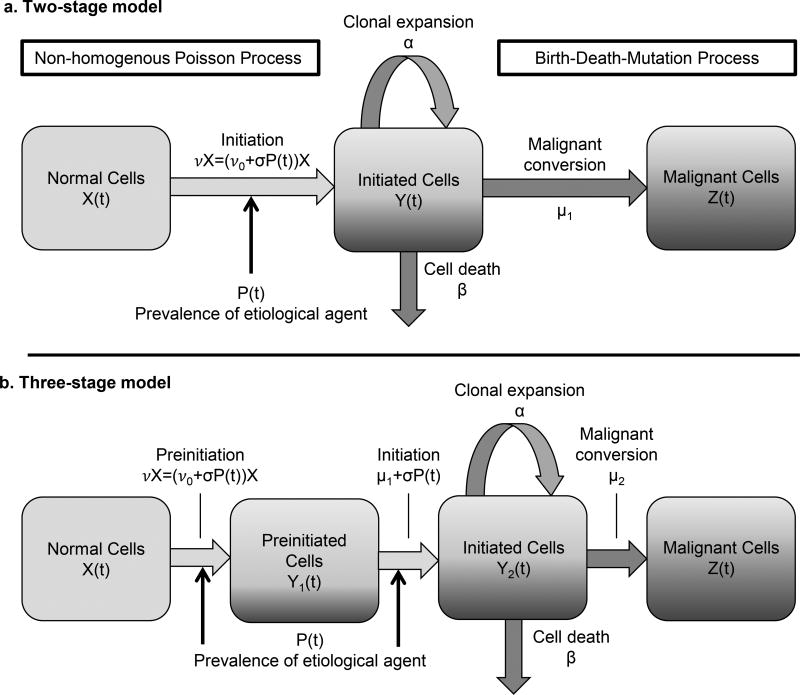

Multistage clonal expansion models, a class of continuous-time Markov chain models, were developed under the initiation–promotion–malignant-conversion paradigm and have been extended to include multiple preinitiation steps [1, 2, 22, 23]. We modify both two-stage and three-stage models by making the rates of the first destabilizing mutations dependent on the population-level prevalence of the associated etiological agent (an assumption first used by Hazelton et al. [6]). The model variables and parameters are given in Table 1, and a schematic of the two-stage model is shown in Figure 1a. Modeled cancer survival x1(t) is defined as the probability that an individual has no malignant cells at age t. We do not include an explicit reporting rate to model the time between the first malignant cell and tumor detection. Although modeling such a rate is useful when modeling individual-level data, it is not separately identifiable in practice for population-level data.

Table 1. Model parameters.

Parameters and identifiable parameter combinations of a multistage clonal expansion (MSCE) model with two-stages and population-level etiological agent prevalence.

| Parameters | |

|---|---|

| X | Number of normal cells, X = X(0) |

| ν0 | Baseline per-cell mutation rate for normal cells (asymmetric division) |

| ρ | Relative risk of an initiating mutation in the presence of the etiological agent |

| σ | Initiation rate due to the etiological agent, σ = ν0(ρ − 1) |

| P(t) | Population-level, age-specific prevalence of the etiological agent |

| α | Initiated cell clonal expansion rate (symmetric division) |

| β | Initiated cell death rate |

| μ1 | Initiated cell malignant conversion rate (asymmetric division) |

|

| |

| Identifiable parameter combinations | |

| p | Net cell proliferation (Eqs. (4) and (7)) |

| q | Malignant conversion (Eqs. (4) and (7)) |

| r | Background tumor initiation (Eqs. (5) and (8)) |

| s | Agent-related tumor initiation (Eqs. (6) and (9)) |

Figure 1. Two- and three-stage clonal expansion model diagrams.

a) Diagram of the two-stage clonal expansion model with initiation dependent on the etiological agent prevalence. Multistage clonal expansion models are continuous-time Markov chain models that follow the initiation– promotion–malignant-conversion hypothesis of carcinogenesis. b) Diagram of the three-stage clonal expansion model. In this model, cells require two rare events before clonal expansion. Both preinitation and initiation rates are dependent on the etiological agent prevalence.

In this model, the tumor detection rate is wrapped into the malignant conversion rate. The model hazard is defined as

and corresponds to age-specific cancer incidence data. The survival and hazard of the two-stage clonal expansion model at age t is found by numerically solving for x1(t) and x2(t) in Eq. (1), where x3(t) and x4(t) can be treated as dummy variables,

| (1) |

with initial conditions x1(0) = 1, x2(0) = x3(0) = 1, x4(0) = −μ1. The equations for the three-stage clonal expansion model, technical details of the models, and theoretical proofs are left to the supplementary material.

One way to formulate the initiation rate is as the sum of the baseline mutation rate times the probability of not being exposed to the etiological agent and the baseline mutation rate times the probability of being exposed to the etiological agent times the relative risk given exposure:

| (2) |

We can reparameterize this equation as

| (3) |

where σ = ν0(ρ − 1). This equation also represents the alternate formulation where the initiation rate is the sum of an initiation rate related to the etiological agent and the baseline initiation rate related to all other factors. This formulation allows us to estimate the fraction of cases resulting from the etiological agent versus other factors. When estimating P(t) instead of using data, σ/ν0 and P(t) form an identifiable combination, meaning that their product can be estimated from the incidence data but that their values cannot individually be estimated (see Corollary 1 in the supplementary material). Thus, when estimating P(t), we determine the relative prevalence between different ages or birth-cohorts rather than the absolute prevalence. The error structure for estimates of P(t) will depend on its parameterization (e.g., number of spline knots).

For the two-stage model, four parameters can be estimated (i.e., are identifiable) from prevalence and incidence data, namely

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

For rare mutations (μ1 ≪ 1) and biologically reasonable growth rates, parameter p2 is approximately equal to −(α−β−μ1), i.e., the negative of the net cell proliferation rate, and q2 is on the order of the malignant conversion rate μ1. Parameters r2 and s2 are related to the background and agent-related tumor initiation rates.

We also consider the three-stage model, which is identical to the two-stage model except for an additional preinitiation stage before clonal expansion (Figure 1b, details in the supplementary material, [24]). In this case we can also estimate four parameters, namely,

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

Age-specific cancer incidence data corresponds to the model hazard or incidence function (details in the supplementary material). The age-specific etiological agent prevalence P(t) can be either be taken as known through data or it can be treated as an unknown to be estimated.

The two- and three-stage models with constant parameters are associated with distinct age-specific model hazard shapes [23]. The two-stage model flattens out with increasing age and can display peaks when there are cohort effects. The three-stage model, on the other hand, is characterized by a linear phase and does not decrease (on the time-span of human lives) without cohort effects. The choice of model is typically based on incidence shape, and likelihood-based model selection is used when needed. Biological evidence can be a useful corroboration.

In this formulation, we model the etiological agent as impacting the initiation rate. In previous work, we considered time-varying promotion or malignant conversion [12], and here we considered a model where the etiological agent impacts the promotion rate instead. However, that model generally did not fit the data as well and we will not discuss the results in detail here (selected results are presented in the supplementary material).

Analytic framework

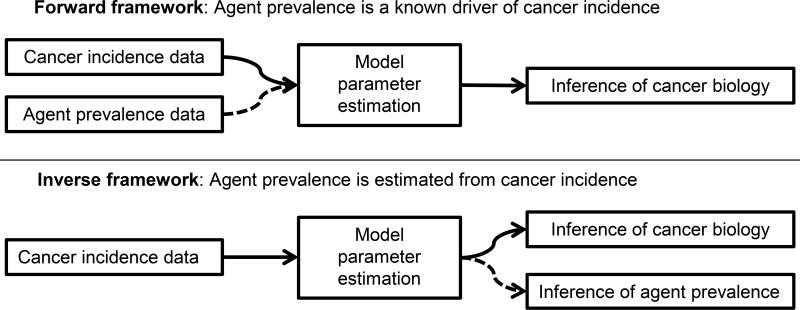

We conduct two types of analyses, frameworks for which are depicted in Figure 2. In the first (forward framework) we assume that the agent prevalence is known. We then use the agent prevalence and cancer incidence data to estimate the MSCE model parameters, including the background cancer initiation (r), the initiation rate due to the etiological agent (s), and the tumor promotion (p) and malignant conversion rates (q). In the second type of analysis (inverse framework), we use only cancer incidence data to infer the etiological agent prevalence (P(t)) as well as the MSCE model parameters, including the relative background and agent-dependent initiation rates.

Figure 2. Forward and inverse analytic frameworks.

The analytic framework depends on whether etiological agent prevalence is known (forward framework) or is estimated in addition to the model’s cancer biology parameters (inverse framework).

Case studies

We use three case studies as illustrative examples: H. Pylori and gastric cancer, smoking and lung cancer, and HPV and oral cancer.

Case study 1. H. pylori and gastric cancer

Since H. pylori infections are known to occur in childhood and persist unless treated, we assume that H. pylori infection status does not vary over the lifetime (P(t) ≡ P), as in [17], but that prevalence varies by birth cohort. Gastric cancer is modeled with the three-stage MSCE model with age-independent parameters and prevalence of H. pylori affecting both the preinitiation and initiation rates [24]. The three-stage model was chosen to model gastric cancer because its age-specific incidence is consistent with the three-stage model hazard shape, i.e., the incidence does not peak or flatten out [23]. We first estimate the model parameters using the NHANES H. pylori data for both men and women, and the SEER gastric cancer incidence data (forward framework). Later, H. pylori prevalence is estimated along with model parameters from cancer incidence alone (inverse framework).

Case study 2. Smoking and lung cancer

Smoking prevalence varies by age and birth cohort. Lung cancer is modeled with the three-stage MSCE model with age-independent biological parameters and with prevalence of smoking affecting the initiation and preinitiation rates. Comparison of two- and three-stage model fits indicated that lung cancer incidence was more consistent with the three-stage model. Carcinogenesis model parameters are estimated using the modeled smoking prevalence (forward framework). We do not use the inverse framework for lung cancer because the shape of age-specific smoking prevalence effects changes significantly over the available data (Figure S1b and c), making the estimation problem computationally infeasible for this case study.

Case study 3. HPV and HPV-related oral cancer

Studies of age-specific oral HPV prevalence, which have only recently begun, do not span enough years to disentangle age and cohort effects. Hence, we assume that the age-specific prevalence of oral HPV has the same shape as female cervicogenital HPV prevalence (1970 reference cohort). Birth cohort patterns on oral HPV prevalence are allowed to be different for men and women and be different from the genital cohort effects. HPV-related oral cancer is modeled with a two-stage MSCE model because the cancer incidence peaks and comes down, consistent with a two-stage model with cohort effects. Birth cohort effects on HPV prevalence, in addition to carcinogenesis model parameters, are estimated for men and women (inverse framework). Because oral HPV has only been tested for since 2009, we cannot use the forward framework for the HPV-related oral cancer case study.

Model fitting and parameter estimation

Following the usual Age–Period–Cohort framework [12, 25–28], we assume that the prevalence of the etiological agent is related to both the age t and birth cohort c,

| (10) |

where gA and gC are functions (natural splines, here) of age t and cohort c and (spline) parameters θt and θc, respectively. The age- and cohort-specific incidence rate λ is given by the model hazard,

| (11) |

where π represents all of the parameters of the MSCE model (see formulation of model hazard h in the supplementary material). Hence, in this formulation, age and cohort effects are on the prevalence of the etiological agent, not on the carcinogenesis parameters directly (as they were in our previous work [12]).

We assume that cancers cases are independent and Poisson-distributed, so that the likelihood for observed cases {xi} with corresponding population-at-risk sizes {ni} under these models is given by

| (12) |

where ηi = ni · λ(π,θt,θc;ti,ci).

We minimized the negative log-likelihood of the model with a Davidson–Fletcher–Powell algorithm in the R (v3.3.1) and gFortran versions of the Bhat package [29].

Results

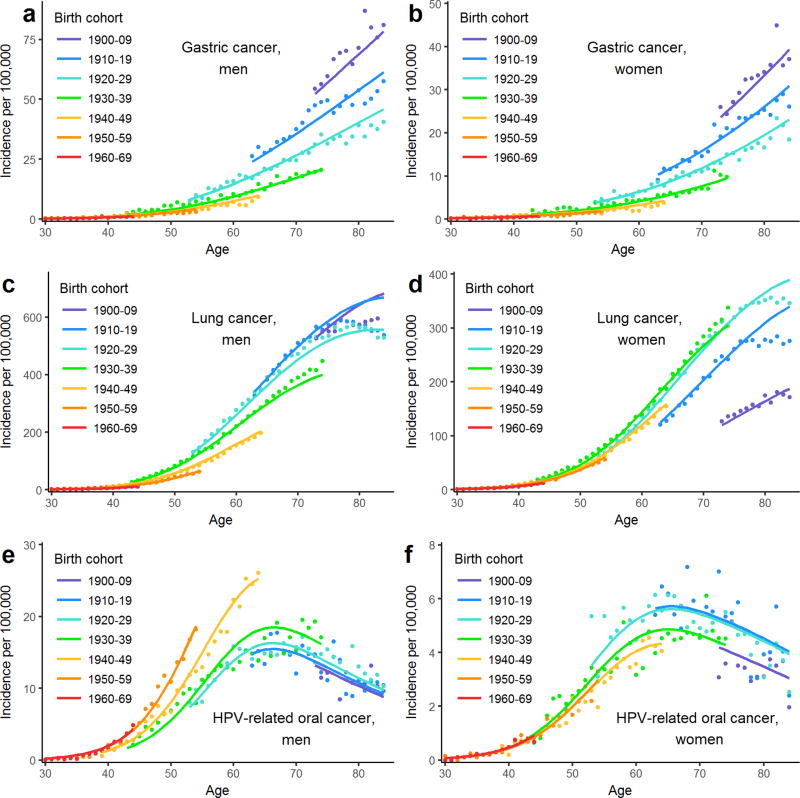

Model fits to age-specific cancer incidence data by birth cohort are presented in Figure 3a–f and are discussed in the following sections. Corresponding plots of predicted cancer incidence by birth cohort are available in the supplementary material (Figure S2a–f).

Figure 3. Gastric, lung, and HPV-related cancer incidence and model fits.

Incidence and modeled incidence per 100,000 are plotted for men and women by birth cohort of (a and b) intestinal-type noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma (GAC), (c and d) malignant neoplasms of the bronchus and lung (LC), and (e and f) HPV-related oral (oropharyngeal and oral cavity) squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Dots are SEER 9 data, and the lines are the model hazards.

Gastric cancer

Estimation of cancer parameters using cancer incidence and H. Pylori data (forward framework)

A likelihood-ratio test (p-value<0.01) indicated that the model was fit best by assuming that all GAC cases were related to the H. pylori pathway (i.e., r3 ≡ 0) for both men and women. Estimated parameters p3, q3, s3 are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Estimated carcinogenesis parameters for gastric, lung, and HPV-related oral cancer.

The number of stages used for the multistage clonal expansion model used and whether the etiological agent prevalence is assumed (forward framework) or fit (inverse framework) are indicated.

| Cancer | Model | Prevalence | Sex | p ×101 (95% CI) | q×104 (95% CI) | r×103 (95% CI) | s×102 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric | 3-stage | Assumed | Male | −1.29 (−1.37, −1.21) | 1.42 (1.16, 1.75) | † | 2.07 (1.95, 2.19) |

| Female | −0.81 (−0.89, −0.74) | 3.49 (3.07, 3.97) | † | 2.35 (2.03, 2.72) | |||

| Fit | Male | −1.31 (−1.43, −1.19) | 2.42 (1.77, 3.31) | † | 1.83 (1.69, 1.97 | ||

| Female | −0.71 (−0.82, −0.61) | 6.05 (4.99, 7.33) | † | 2.34 (1.90, 2.90) | |||

| Lung | 3-stage | Assumed | Male | −1.84 (−1.87, −1.82) | 2.63 (2.49, 2.78) | 2.21 (2.06, 2.38) | 4.98 (4.92, 5.04) |

| Female | −1.87 (−1.91, −1.84) | 1.89 (1.73, 2.07) | 4.04 (3.86, 4.22) | 5.33 (5.21, 5.46) | |||

| HPV-related oral | 2-stage | Fit | Male | −2.10 (−2.15, −2.05) | 0.44 (0.38, 0.51) | † | 0.30 (0.29, 0.31) |

| Female | −1.97 (−2.07, −1.88) | 1.13 (0.87, 1.47) | † | 0.051 (0.048, 0.055) |

likelihood-ratio test indicates r≡0.

We compare GAC incidence-by-cohort data (points) with the resulting model predictions (lines) in Figure 3a and b. The figures demonstrate that GAC incidence has decreased considerably between the birth cohorts of the 1900s and the 1970s in a pattern that is consistent with the reduced prevalence of H. pylori over the same time frame. The three-stage MSCE model with three parameters and initiation rate varying by birth-cohort (driven by the relative H. Pylori prevalence by cohort) fits the GAC trends well.

Estimation of both cancer parameters and H. Pylori prevalence by cohort (inverse framework)

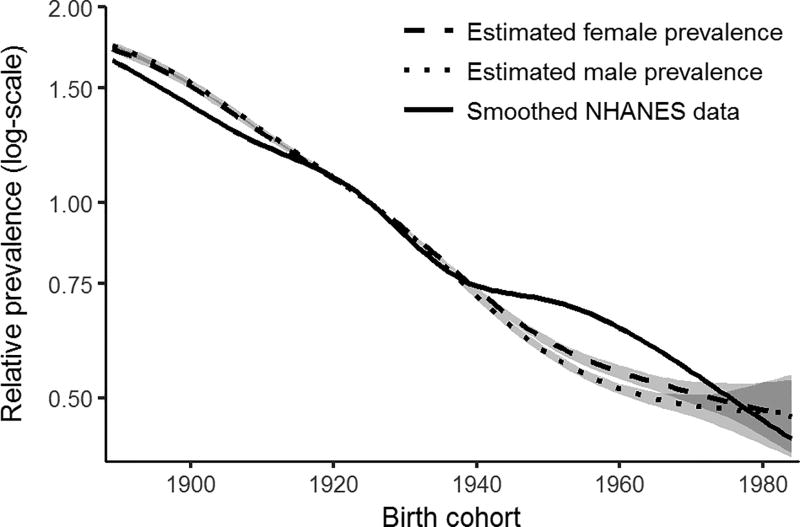

Next, we consider the extent to which H. pylori prevalence can be estimated from incidence data. In addition to parameters p3, q3, and s3, we estimate H. Pylori prevalence by birth cohort, parameterized as a natural spline with five degrees of freedom. Because prevalence and s3 form an identifiable product, we can only estimate relative prevalence; here, we use 1925 as the reference birth cohort (when prevalence was approximately 50% (Figure S1a)). Table 2 shows the estimated cancer parameters in this framework; differences between biological parameter estimates when estimating H. Pylori prevalence (here) or not (previous framework) are relatively small. The estimated prevalence for men and women is plotted in Figure 4 with the smoothed NHANES data for comparison. The estimated prevalences both match the data well, with only minor discrepancies for those born in 1950s and ’60s (note that the discrepancies would have manifested for different birth cohorts had a different reference cohort been chosen). The corresponding GAC incidence data by cohort and the model predictions under this framework are given in the supplementary material (Figure S3a–b).

Figure 4. Relative H. pylori prevalence.

Relative prevalence estimated from gastric cancer incidence is compared to estimates from NHANES, with 95% likelihood-based confidence intervals, taking 1925 to be the reference birth cohort (the cohort for which prevalence was approximately 50%).

Lung cancer

Estimation of cancer parameters using cancer incidence and smoking prevalence data (forward framework)

Estimated parameters p3, q3, r3, s3 are listed in Table 2. The models, which have only four degrees of freedom and are driven by smoking prevalence by cohort and gender, fit the data well up until the late-life period, where some deviations are seen (Figure 3c and d). The model estimates that the majority of lung cancer cases are due to smoking (or other effects captured by the cohort trends); the exact estimates depend on the smoking prevalence, but, for example, for the 1960 birth cohort, the model estimates 97.3% (97.1–97.4%) of lung cancers in men and 92.2% (91.2–92.5%) in women were caused by smoking. Over all of the cohorts, the model estimates that the relative risk of an initiating mutation if one is smoking is ρ=23.5 (22.1–25.0) for men and 14.2 (13.9–14.5) for women. The incidence-by-cohort plots suggest that the incidence of LC has varied dramatically in a cohort fashion, consistent with the patterns of smoking in the U.S. Predicted cancer incidence by cohort is available in the supplementary material (Figure S2c and d).

HPV-related oral cancer

Estimation of both cancer parameters and relative oral HPV prevalence by cohort using cancer incidence and genital HPV age-specific prevalence (inverse framework)

Because oral HPV-testing is a recent development, we must estimate the cohort effects of oral HPV from the cancer incidence data. As a first step, we assume that the age-specific prevalence of oral HPV in men and women in 1970 is a scaling of the age-specific prevalence of cervicogenital HPV in 1970. A likelihood-ratio test (p-value<0.01) preferences the model without background initiation (r2 ≡ 0) for both men and women, so we estimate only p2, q2, s2 (Table 2) and the parameters for a natural spline with eight degrees of freedom. Model fits are plotted in Figure 3e and f. Predicted cancer incidence by cohort is available in the supplementary material (Figure S2e and f).

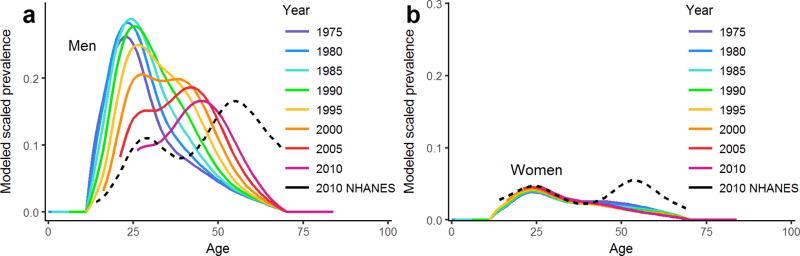

There is more spread in the data for this cancer than the two previously considered, resulting in larger model residuals, particularly for women, but the overall patterns in the age-specific incidence by birth cohort are captured. A comparison of the estimated relative birth cohort effects is given in the supplementary material (Figure S4). We plot the modeled cross-sectional, age-specific prevalence of oral HPV for men (Figure 5a) and women (Figure 5b) between 1975 and 2010. Because prevalence is identifiable only up to a scalar, we scale the estimated prevalence to the 2009–10 estimates of US age-specific oral HPV prevalence from the NHANES survey [30]. A bimodal pattern emerges for men when plotting estimated oral HPV prevalence by calendar year; this pattern is qualitatively consistent with the 2009–10 NHANES data, though shifted by approximately a decade. For women, the prevalence modeled from the cancer incidence does not capture the second peak in oral HPV prevalence seen in the data. Instead, the model suggests that the second prevalence mode may be aging out. This interpretation is driven by the cancer data (Figure 3f), where incidence for women, unlike for men, has been decreasing since the 1920–29 cohort. Discrepancies between the estimates based on cancer incidence and the data may be due to misspecification of the age effects, unaccounted-for period effects, or other factors affecting the temporal relationship between oral HPV and cancer (e.g., smoking, alcohol use, or other oral cancer risk factors).

Figure 5. Modeled age-specific prevalence of oral HPV.

Modeled prevalence by calendar year is estimated from models of HPV-related oral cancer incidence, for a) men and b) women. The dotted lines give the unadjusted cubic spline approximations of oral HPV prevalence in men and women in NHANES 2009–10 [30].

Discussion

In this study we assessed whether population-level cancer and risk factor data can be leveraged to infer cancer mechanisms and improve cancer rate projections, and, conversely, whether cancer risk factor patterns can be inferred from age-specific cancer incidence trends. Despite the analysis simplifications, modeling exposures by age and birth-cohort and relying on the MSCE model formulation to integrate and synthesize the information from both scales has proven an effective way to explore the complex relationship between risk factor prevalence and cancer incidence data at the population level. This result is particularly helpful when one considers that, in general, individual-level data for assessing risk factors are rare.

Advantages and challenges of incorporating risk factor data into analyses of cancer incidence data

A strength of this approach is the ability to achieve good fits parsimoniously, that is, with few parameters. The GAC and LC models are able to reproduce forty years of cancer incidence data with only three and four parameters, respectively, and the risk factor prevalence data. Our analyses demonstrate that, when considering risk factors with a strong causal link to a type of cancer, incorporating data from risk factor prevalence into analyses and projections of cancer incidence might be preferable to non-parametric approaches such as age–period–cohort analyses, which suffer from identifiability problems and over-fitting concerns [11, 12, 22]. By using population-level data, however, we lose the ability to assess heterogeneities in risk. For example, the risk of gastric cancer from H. pylori infection varies widely depending on some virulence factors of the pathogen and differences in host susceptibility [31]. Nevertheless, we can capture the overall temporal trend in incidence from the prevalence as well as risk profiles that average over the existing heterogeneities. We note, then, that the estimated biological parameters represent population averages that likely have significant individual variability depending on the pathogen and host characteristics.

Modeling GAC and LC incidence using H. pylori or smoking prevalence data gave good fits to the data in general, largely thanks to the strong relationship of these risk factors to the corresponding cancer. There is more uncertainty in the OSCC model, however. There are at least two major reasons for this. First, the SEER cancer registry does not record tumor HPV testing. We must rely, as previous studies have done [12, 32–34], on a presumed HPV-related status based on the location of the cancer. Because not all HPV-related cancers are HPV-positive, some error is introduced into the data. Second, because oral HPV infection has only been tested for at the population level in recent years (NHANES began oral HPV testing in 2009 [18]), it is not yet possible to determine which signals in the data are related to the age of the participant and which are due to cohort effects. Several studies of cervicogenital HPV prevalence and HPV serum antibodies have concluded that cohort effects, likely related to changes in sexual behaviors, have driven patterns of genital HPV infection [21, 35, 36], and it is likely that cohort effects have similarly played a role in patterns of HPV oral prevalence. In this study, we assumed that the age-specific prevalence of oral HPV in 1970 was proportional to cervicogenital prevalence. While unlikely to be exactly true, this assumption is not completely unreasonable as HPV infection for both sites is largely driven by sexual contact and as there is a correlation between individual (and population-level) oral and genital infections [21, 37]. Still, any misspecification of the shape of the age effects in the model will propagate errors. Moreover, there may be period effects (i.e., calendar year dependent effects) that we did not account for in the model. Hence, the exact quantitative estimates of past oral HPV infection should not be given much weight. Nevertheless, we were able to broadly capture the bimodal prevalence pattern of oral HPV prevalence in the U.S. observed in 2009–10 in men [30]. At the time, it was not clear whether this bimodal pattern was an age effect or a cohort effect. Our results demonstrate that the data can be explained as resulting from cohort variations in HPV infection risk.

A major limitation of our study is that we restricted the analyses to a single risk factor per cancer. It is known, for instance, that smoking, alcohol consumption, and diet are also important covariates for OSCC [38]. Besides smoking, other environmental and occupational exposures, such as radon and asbestos, are relevant lung cancer risk factors [39]. Similarly diet, smoking, genetic factors, and medical conditions such as pernicious anemia have been associated with GAC [40]. However, the risk factors considered in all three case studies here are likely responsible for the large majority of the corresponding cancers, and here we show that accounting for their temporal patterns can improve analyses of cancer incidence trends and that one could also potentially estimate trends of the major risk factor for a specific cancer, if one exists, directly from cancer incidence data. Future work will consider two or more exposures simultaneously.

In this analysis, we assumed that the mechanism of action of the etiological agents was on tumor initiation. Individual-level analyses of prospective cohort data, however, have suggested that this not always the case and that exposure-related promotion is a relevant mechanism in multiple cancers, such as smoking-related lung cancer [3, 4, 41], as well as in other exposure–cancer pairs [5, 42, 43]. We found that an MSCE model where the etiological agent increased the net cell proliferation did not fit the cancer incidence data as well (see supplement). This finding does not necessarily mean that promotion is not the mechanistic pathway; there may be non-linear or exposure magnitude effects that we cannot capture with the population-level data available. Nevertheless, the excellent fits and predictions obtained with as few as four parameters, suggest that, as a first approximation, assuming the effects on initiation is adequate for predicting population-level trends.

Estimation of risk factor prevalence from cancer incidence data only

Our analyses indicate that when there is a strong causal link between a risk factor and a cancer outcome, it is possible to extrapolate and estimate risk factor prevalence for time periods without direct data. A major barrier to this kind of estimation has been the long and highly variable temporal distance between the risk factor and the cancer outcome. Here, by leveraging MSCE models, we use basic carcinogenesis mechanisms to understand the temporal structure of these delays, allowing us to both predict future cancer incidence knowing current risk factor prevalence and to estimate previous risk factor prevalence from current cancer incidence.

Estimation of the relative contribution of background versus agent-related initiation

Our approach explicitly differentiates between tumor initiation due to the etiological agent versus due to background causes. We find, however, that in practice the models often neglect the background initiation pathway (i.e., we estimate the background rate to be r = 0). This phenomenon occurs in part because the model calibration will wrap any other pathway effects with similar temporal patterns into the agent pathway, resulting in a potential overestimation of the fraction of cases due to the etiological agent of interest. Hence, while the LC model estimated that more than 90% of the LC cases were due to smoking, attributable fraction estimates suggest that the true values are likely somewhat less than this—e.g., the U.S. Surgeon General estimates that 80–90% of LC is caused by smoking [15], although this varies by gender and year. The data used covers the period of time where smoking-related lung cancer incidence was at its highest, which likely biases our results to higher attributable fraction estimates. Our analysis could be refined if data on case exposure were available (e.g., identification of LC cases as never, former and current smokers, or HPV status of OSCC tumors). That being said, our analyses—which are based on models that account for not only random or agent-caused mutations but also tumor cell clonal expansion, long-term cancer registry data, and temporal patterns of leading risk factors—suggest that, at least for these cancers, a majority of cases can be attributed to these environmental exposures.

Interest and discussion concerning the proportion of cancer cases (or cancer types) attributable to environmental factors, hereditary factors, or “bad luck” mutations has increased in recent years following the publication of Tomasetti and Vogelstein’s analysis [44, 45] that suggested that two-thirds of the variation in cancer risk between cancers of different tissues could be explained by differences in stem cell division rates. This work has been very controversial, in part due to misinterpretation of their conclusions, and many others have weighed in on this topic (e.g., [46–51]). Our analyses of specific risk factors and cancers using mechanistic models, which explicitly account for clonal expansion and evolution in addition to random and environmentally driven-mutations, show the relevance of both environmental and random effects in the carcinogenesis process.

Conclusion

Relating risk factor patterns to cancer incidence is difficult: the temporal relationships between exposures and outcomes are complex. We have demonstrated that integrating population-level data on both cancer and exposures though mechanistic, mathematical models can be a first step to systematically testing relationships between exposures and cancer risk, particularly when individual-level data representative of a population is lacking.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Analysis of trends in risk-factor prevalence and cancer incidence can shed light on cancer mechanisms and the way that carcinogen exposure through time shapes the risk of cancer at different ages.

Quick guide to equations and assumptions.

Assumptions

Cancer arises from a series of rare, stochastic events, and the numbers of pre-malignant and malignant cells is modeled as a continuous-time Markov chain (Figure 1).

The first initiating mutation is modeled as a non-homogeneous Poisson process. We assume that this rate is dependent on the age-specific prevalence of the etiological agent in the population.

Clonal expansion and malignant conversion of initiated cells is modeled as a birth–death– mutation process.

The model hazard corresponds to age-specific cancer incidence data.

Key equations

Modeled cancer survival x1(t) is defined as the probability that an individual has no malignant cells at age t. The model hazard is defined as

and corresponds to age-specific cancer incidence data. The per-cell initiating mutation rate ν(t) can be written as

where ν0 is the baseline initiation rate, P(t) is the prevalence of the etiological agent at age t, and ρ is the relative risk of initiation given exposure to the etiological agent. If α is the cell growth rate, β the cell death rate, μ1 the malignant conversion mutation rate, and X the number of normal cells in the tissue, then the survival and hazard of the two-stage clonal expansion model at age t are found by numerically solving for x1(t) and x2(t), respectively, in the following system of equations, in which x3(t) and x4(t) can be treated as dummy variables,

with initial conditions x1(0) = 1, x2(0) = 0, x3(0) = 1, x4(0) = −μ1.

Acknowledgments

All authors were supported by NIH grant U01CA182915.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement. All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Moolgavkar SH, Venzon DJ. Two-event models for carcinogenesis: incidence curves for childhood and adult tumors. Mathematical Biosciences. 1979;47(1–2):55–77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moolgavkar SH, Knudson AG. Mutation and cancer: a model for human carcinogenesis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1981;66(6):1037–52. doi: 10.1093/jnci/66.6.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hazelton WD, Moolgavkar SH, Curtis SB, Zielinski JM, Ashmore JP, Krewski D. Biologically based analysis of lung cancer incidence in a large Canadian occupational cohort with low-dose ionizing radiation exposure, and comparison with Japanese atomic bomb survivors. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A. 2006;69(11):1013–38. doi: 10.1080/00397910500360202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meza R, Hazelton WD, Colditz GA, Moolgavkar SH. Analysis of lung cancer incidence in the Nurses’ Health and the Health Professionals’ Follow-Up Studies using a multistage carcinogenesis model. Cancer Causes & Control. 2008;19(3):317–28. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson DB. Multistage modeling of leukemia in benzene workers: a simple approach to fitting the 2-stage clonal expansion model. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;169(1):78–85. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hazelton WD, Curtius K, Inadomi JM, Vaughan TL, Meza R, Rubenstein JH, et al. The role of gastroesophageal reflux and other factors during progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(7):1–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0323-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtius K, Hazelton WD, Jeon J, Luebeck EG. A Multiscale Model Evaluates Screening for Neoplasia in Barrett’s Esophagus. PLOS Computational Biology. 2015;11(5):e1004272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Koning HJ, Meza R, Plevritis SK, Ten Haaf K, Munshi VN, Jeon J, et al. Benefits and harms of computed tomography lung cancer screening strategies: A comparative modeling study for the U.S. Preventive services task force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160(5):311–320. doi: 10.7326/M13-2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meza R, Jeon J, Renehan AG, Luebeck EG. Colorectal cancer incidence trends in the United States and United Kingdom: evidence of right- to left-sided biological gradients with implications for screening. Cancer research. 2010;70(13):5419–29. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moolgavkar SH, Holford TR, Levy DT, Kong CY, Foy M, Clarke L, et al. Impact of reduced tobacco smoking on lung cancer mortality in the united states during 1975–2000. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104(7):541–548. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meza R, Chang JT. Multistage carcinogenesis and the incidence of thyroid cancer in the US by sex, race, stage and histology. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):789. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2108-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brouwer AF, Eisenberg MC, Meza R. Age Effects and Temporal Trends in HPV-Related and HPV-Unrelated Oral Cancer in the United States: A Multistage Carcinogenesis Modeling Analysis. PLOS One. 2016;11(3):e0151098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anand P, Kunnumakara AB, Sundaram C, Harikumar KB, Tharakan ST, Lai OS, et al. Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes. Pharmaceutical Research. 2008;25(9):2097–2116. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9661-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Biological Agents. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 15.U S Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress A Report of the Surgeon General. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. 2018 Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/

- 17.Yeh JM, Hur C, Schrag D, Kuntz KM, Ezzati M, Stout N, et al. Contribution of H. pylori and Smoking Trends to US Incidence of Intestinal-Type Noncardia Gastric Adenocarcinoma: A Microsimulation Model. PLoS Medicine. 2013;10(5):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2018 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

- 19.Holford TR, Levy DT, McKay LA, Clarke L, Racine B, Meza R, et al. Patterns of birth cohort-specific smoking histories, 1965–2009. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46(2):e31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holford TR, Levy DT, McKay LA, Clarke L, Racine B, Meza R, et al. CISNET Publication Support and Modeling Resources: Patterns of Birth Cohort-Specific Smoking Histories, 1965–2009. 2013 https://resources.cisnet.cancer.gov/projects/#shg/tce/summary.

- 21.Brouwer AF, Eisenberg MC, Carey TE, Meza R. Trends in HPV cervical and seroprevalence and associations between oral and genital infection and serum antibodies in NHANES 2003–2012. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2015;15(1):575. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1314-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luebeck EG, Moolgavkar SH. Multistage carcinogenesis and the incidence of colorectal cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99(23):15095–15100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222118199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meza R, Jeon J, Moolgavkar SH, Luebeck EG. Age-specific incidence of cancer: Phases, transitions, and biological implications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(42):16284–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801151105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brouwer AF, Meza R, Eisenberg MC. Parameter estimation for multistage clonal expansion models from cancer incidence data: a practical identifiability analysis. PLOS Computational Biology. 2017 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holford TR. The Estimation of Age, Period and Cohort Effects for Vital Rates. Biometrics. 1983;39(2):311–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holford TR. Understanding the Effects of Age, Period, and Cohort on Incidence and Mortality Rates. Annual Review of Public Health. 1991;12(1):425–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.12.050191.002233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clayton D, Schifflers E. Models for temporal variation in cancer rates. I: Age-period and age-cohort models. Statistics in Medicine. 1987;6(4):449–67. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clayton D, Schifflers E. Models for temporal variation in cancer rates. II: Age-period-cohort models. Statistics in Medicine. 1987;6(4):469–81. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luebeck G, Meza R. Bhat: General likelihood exploration; 2013. R package version 0.9–10 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RKL, Tong Zy, Xiao W, Kahle L, et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009–2010. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(7):693–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wroblewski LE, Peek RM, Wilson KT. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: Factors that modulate disease risk. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2010;23(4):713–739. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00011-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown LM, Check DP, Devesa SS. Oropharyngeal cancer incidence trends: diminishing racial disparities. Cancer Causes & Control. 2011;22(5):753–63. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9748-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown LM, Check DP, Devesa SS. Oral cavity and pharynx cancer incidence trends by subsite in the United States: changing gender patterns. Journal of Oncology. 2012;2012:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2012/649498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, Gillison ML. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(4):612–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desai S, Chapman R, Jit M, Nichols T, Borrow R, Wilding M, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus antibodies in males and females in England. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38(7):622–629. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820bc880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryser MD, Rositch A, Gravitt PE. Modeling of US human papillomavirus (HPV) seroprevalence by age and sexual behavior indicates an increasing trend of HPV infection following the sexual revolution. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2017;216(5):604–611. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinau M, Hariri S, Gillison ML, Broutian TR, Dunne EF, Tong Zy, et al. Prevalence of cervical and oral human papillomavirus infections among US women. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014;209(11):1739–43. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petti S. Lifestyle risk factors for oral cancer. Oral Oncology. 2009;45(4–5):340–350. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alberg AJ, Ford JG, Samet JM. Epidemiology of lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition) Chest. 2007;132(3 SUPPL):29S–55S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forman D, Burley VJ. Gastric cancer: global pattern of the disease and an overview of environmental risk factors. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Gastroenterology. 2006;20(4):633–649. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schollnberger H, Beerenwinkel N, Hoogenveen R, Vineis P. Cell selection as driving force in lung and colon carcino-¨ genesis. Cancer research. 2010;70(17):6797–803. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hazelton WD, Luebeck EG, Heidenreich WF, Moolgavkar SH. Analysis of a historical cohort of Chinese tin miners with arsenic, radon, cigarette smoke, and pipe smoke exposures using the biologically based two-stage clonal expansion model. Radiation research. 2001;156(1):78–94. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0078:aoahco]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luebeck EG, Heidenreich WF, Hazelton WD, Paretzke HG, Moolgavkar SH. Biologically based analysis of the data for the Colorado uranium miners cohort: age, dose and dose-rate effects. Radiation research. 1999;152(4):339–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science. 2015;347(6217):78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1260825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomasetti C, Li L, Vogelstein B. Stem cell divisions, somatic mutations, cancer etiology, and cancer prevention. Science. 2017;355(6331):1330–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf9011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu S, Powers S, Zhu W, Hannun YA. Substantial contribution of extrinsic risk factors to cancer development. Nature. 2015;529(7584):43–47. doi: 10.1038/nature16166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sornette D, Favre M. Debunking mathematically the logical fallacy that cancer risk is just “bad luck”. EPJ Nonlinear Biomedical Physics. 2015;3(1):10. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nunney L, Maley CC, Breen M, Hochberg ME, Schiffman JD. Peto’s paradox and the promise of comparative oncology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2015;370(1673):20140177–20140177. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinberg CR, Zaykin D. Is Bad Luck the Main Cause of Cancer? Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2015;107(7):1–4. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noble R, Kaltz O, Nunney L, Hochberg ME. Overestimating the role of environment in cancers. Cancer Prevention Research. 2016;9(10):773–776. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nowak MA, Waclaw B. Genes, environment, and “bad luck”. Science. 2017;355(6331):1266–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.