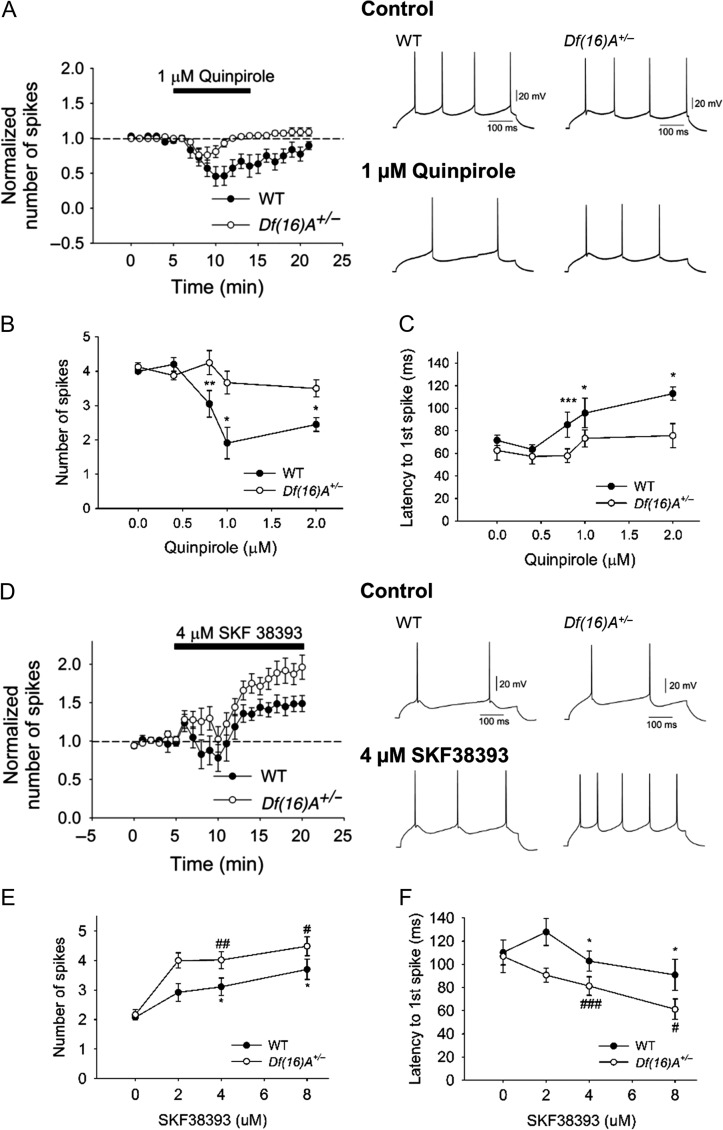

Figure 2.

The inhibitory effect of D2R activation of PFC pyramidal neuron excitability is reduced whereas the excitatory effect of D1R activation of PFC pyramidal neuron excitability is enhanced in Df(16)A+/− mice. (A) Bath application of 1 μM quinpirole-induced greater decrease in the cell excitability in WT (N = 7, n = 8, P = 0.014, Wilcoxon test) than Df(16)A+/− (N = 7, n = 10, Wilcoxon test, P = 0.10) mice. Right panel illustrates the effect of quinpirole on the action potential firing induced by depolarizing current injection (150–250 pA) in single neurons from WT and Df(16)A+/− mice. (B) Quinpirole decreased cell excitability in a dose-dependent manner (0, 0.4, 0.8, 1.0, and 2.0 μM) in WT mice (before and after quinpirole, 0 μM: N = 3, n = 4, P = 0.50; 0.4 μM: N = 3, n = 4, P = 0.25; 0.8 μM: N = 7, n = 14, P = 0.004; 1 μM: N = 7, n = 8, P = 0.014; 2 μM: N = 5, n = 5, P = 0.04, Wilcoxon test) but led to significantly less decrease in Df(16)A+/− mice (before and after quinpirole, 0 μM: N = 3, n = 4, P = 0.41; 0.4 μM: N = 3, n = 4, P = 1.00; 0.8 μM: N = 7, n = 11, P = 0.17; 1 μM: N = 7, n = 10, P = 0.10; 2 μM: N = 3, n = 6, P = 0.84, Wilcoxon test; WT vs. Df(16)A+/−: P = 0.017, two-way ANOVA). (C) Dose-dependent increase in first spike latency in WT mice (before and after quinpirole, 0 μM: n = 4, P = 0.63; 0.4 μM: n = 4, P = 0.25; 0.8 μM: n = 14, P = 0.0004; 1 μM: n = 8, P = 0.02; 2 μM: n = 5, P = 0.03, Wilcoxon test) was greater than Df(16)A+/− mice (before and after quinpirole, 0 μM: n = 4, P = 0.50; 0.4 μM: n = 4, P = 0.63; 0.8 μM: n = 11, P = 0.30; 1 μM: n = 10, P = 0.16; 2 μM: n = 6, P = 0.31; WT vs. Df(16)A+/−: P = 0.02, two-way ANOVA). (D) Bath application of 4 μM SKF38393 induced less increase in cell excitability in WT (N = 8, n = 9, P = 0.04, Wilcoxon test) than in Df(16)A+/− mice (N = 8, n = 12, P = 0.0023, Wilcoxon test) mice. Right panel illustrates the effect of SKF38393 on the action potential firing induced by depolarizing current injection (100–150 pA) in single neurons from WT and Df(16)A+/− mice. (E) SKF38393 increased cell excitability in a dose-dependent manner (0, 2, 4, and 8 μM) in WT mice (before and after SKF38393, 0 μM: N = 3, n = 4, P = 0.59; 2 μM: N = 4, n = 5, P = 0.13; 4 μM: N = 8, n = 9, P = 0.04; 8 μM: N = 3, n = 5, P = 0.03, Wilcoxon test) but showed significantly greater increase in Df(16)A+/− mice (0 μM: N = 3, n = 4, P = 0.57; 2 μM: N = 3, n = 5, P = 0.06; 4 μM: N = 8, n = 12, P = 0.0023; 8 μM: N = 3, n = 5, P = 0.02, Wilcoxon test; WT versus Df(16)A+/−: P = 0.008, two-way ANOVA). (F) Dose-dependent decrease in first spike latency in Df(16)A+/− mice (before and after SKF38393, 0 μM: n = 4, P = 0.75; 2 μM: n = 5, P = 0.13; 4 μM: N = 8, n = 12, P = 0.0005; 8 μM: n = 5, P = 0.023, Wilcoxon test) was greater than in WT mice (0 μM: n = 4, P = 0.13; 2 μM: n = 5, P = 0.13; 4 μM: n = 9, P = 0.03; 8 μM: n = 5, P = 0.03, Wilcoxon test; WT versus Df(16)A+/−: P = 0.005, two-way ANOVA). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, #P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ##P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ###P < 0.001.