Abstract

Background

Teaching during patient care is an important competency for faculty. Little is known about anesthesiology resident preferences for teaching by anesthesiology faculty in the operating room (OR). If the behaviors and characteristics of anesthesia teaching in the OR that are most valued by residents were identified, faculty could incorporate that best practice to teach residents during OR cases. The objective of this phenomenological study was to interview anesthesiology residents to determine what they perceive the best faculty teachers are doing in the OR to educate residents.

Methods

Thirty randomly selected anesthesiology residents (10 in each post-graduate year class) were interviewed using a semi-structured approach with a predetermined question: “Based on your experiences as a resident, when you think about the best-attending teachers in the OR, what are the best-attending teachers doing in the OR to teach that other faculty maybe are not doing?” Interviews were recorded, transcribed, converted into codes, and grouped into themes derived from the cognitive apprenticeship framework, which includes content, teaching methods, sequencing, and social characteristics.

Results

Resident responses were separated into a total of 134 answers, with similar answers grouped into one of 27 different codes. The most commonly mentioned codes were: autonomy – step back and let resident work through (mentioned by 13 residents), reasoning – explain why attending does things (12), context – teach something relevant to the case (8), commitment – take time to teach (8), literature – bring relevant papers (8), prior knowledge – assess the baseline level (7), flexibility – be open to trying different approaches (7), focus on just a few learning points (6), reflection – ask resident questions (6), provide real-time feedback (6), teach back – ask residents to explain what they were taught in their own words (5), belonging – facilitate communication with the OR team (5), psychological safety – be open and approachable (5), equanimity – stay calm and collected (5), select proper timing for instruction when the resident is not occupied with patient care (5), visualization – use graphs or diagrams (5), and specify learning goals ahead of time (5).

Conclusion

The best practice for OR teaching, as perceived by anesthesia residents, includes social characteristics, such as context, commitment, psychological safety, equanimity, and proper timing, as well as teaching methods, such as autonomy, reasoning, literature, prior knowledge, flexibility, reflection, real-time feedback, and teach back. Further studies can determine if training anesthesiology faculty to incorporate these elements increases the caliber of daily teaching in the OR.

Keywords: anesthesiology, graduate medical education, resident teaching

Introduction

Teaching is an important competency for academic faculty in graduate medical education because the optimal training of residents lays the foundation for high-quality patient care. In addition, academic faculty who score poorly on resident evaluations of their teaching are at risk for not being promoted and may seek counsel on how to improve their teaching.

The teaching of house staff can occur in various environments, such as the classroom, outside of direct patient care. In the classroom setting, for example, the following have been identified as useful: utilizing a clinical case vignette, clearly stating the goals of the talk, showing enthusiasm for the topic, reinforcing learning points, employing graphics or visuals, adding quizzes, providing recommendations about patient care, incorporating references/directions for further reading, eliciting active involvement of residents, and listing take-home messages [1-2]. However, the majority of graduate medical education involves work-related activities by the resident in the hospital or clinic delivering patient care [3]. Teaching in this setting may be challenging due to the need for teaching to occur simultaneously while both the resident and the attending have patient care work to do, the time constraints of faculty, the short stays of patients, and the absence of formal training in the education of the faculty. Desirable attributes for attendings include being clinically competent, clear, organized, accessible, supportive, compassionate, able to establish understanding with learners, provide direction and feedback, exhibit integrity and respect for others, offer a broad repertoire of teaching methods, engage in self-evaluation and reflection, and target teaching to the learners’ level of knowledge [4].

Anesthesia teaching by faculty for anesthesia residents in the OR during the care of an anesthetized patient has several challenges. Teaching occurs during the acute care of a patient that can rapidly change during difficult cases, production pressure exists to get through the list of OR cases in a timely manner, faculty are often covering two anesthetizing locations, and there is a need for both cognitive and technical skills instruction [5]. A study of faculty supervision evaluation by anesthesia residents identified nine key dimensions for the instructor: provides feedback, is available, gives opportunities/fostering resident autonomy, stimulates patient-based learning, demonstrates professionalism, is present during critical events, discusses the perianesthesia management of the patient, shows interpersonal skills, and exhibits concern for safety [6]. A separate study utilized the residents' written feedback to their clinical teachers to identify several themes associated with high teaching scores: use of primary literature to support teaching, explaining why specific management strategies were used, having education-oriented discussion, spending adequate time teaching, teaching to the appropriate level of the resident, demonstrating an active effort in teaching the resident, and imparting significant clinical knowledge [7].

If the teaching behaviors and characteristics of the anesthesiology faculty that are most valued by residents in the OR could be further elucidated, the anesthesiology faculty could incorporate these resident preferences for teaching during OR cases. Resident perception and preferences matters because physicians in anesthesia training are adult learners and, as such, should be involved in the planning and evaluation of their instruction. The perceived value that learners place on educational experiences is a measure of the learning environment and the learning environment can have a strong influence on the effectiveness of teaching.

The objective of this phenomenological study was to interview anesthesia residents to determine what the best faculty teachers are doing in the OR to educate residents.

Materials and methods

The Stanford Institutional Review Board determined that this study did not meet the federal regulations’ definition of human subjects research and was exempt from review. This study employed a qualitative methods design. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research were followed [8].

A phenomenological approach was chosen because the goal was to describe the essence of a phenomenon (OR teaching) by exploring it from the perspective of those (anesthesiology residents) who experience it so as to understand the meaning they ascribe to OR teaching.

Sample size calculation was not performed for this qualitative study, as resident interviews were stopped when the responses no longer resulted in new data for new codes [9].

Using a random number generator, anesthesiology residents from each of the three resident classes at Stanford University Medical Center were selected from January 16 to March 3, 2017. All residents invited to participate agreed, and no incentives were offered for participating.

The participants were interviewed face-to-face by two investigators (S.W., R.V.) using a semi-structured approach with the aim to provide a supportive environment and encourage rich responses. Both investigators participated in all interviews. No written questionnaire was used. The participants were informed that the objective of the research was to understand their perceptions about what makes for good anesthesia teaching by faculty in the OR.

The wording of the main question was created during a meeting of the research team to narrow the research objective. This predefined question was: “Based on your experiences as a resident, when you think about the best-attending teachers in the OR, what are the best teachers doing in the OR to teach that other faculty maybe are not doing?”

If the resident gave a short answer of a few words or less, the resident was prompted with “Please tell us three things or more” as a way to signal that more answers were desirable and to get a more overall depth of content. When the resident was finished speaking, he/she was then asked, “Is there anything we haven't talked about that you want to add?”

The interview audios were digitally recorded and transcribed by the interviewing investigators without identifying data. The interview durations ranged from seven to 12 minutes, and all the interviews occurred in the anesthesia department offices in the hospital.

All de-identified responses remained anonymous. Initial transcripts were read in detail and fragments of the participants' responses were selected and then stored in a spreadsheet with other similar fragments. All six members of the research team sat in a classroom and reviewed and analyzed the fragments and responses to create codes. The participation of several researchers with varying perspectives helps provide multiple observations and conclusions, as this triangulation adds breadth and can facilitate a confirmation of findings.

Names for the codes, either a single word or a few words, were derived directly verbatim from the raw text. The general goal was for each code to be a specific behavior that could be easily understood and communicated to an interested faculty. Transcripts were examined multiple times as additional interviews were completed to provide ongoing comparisons across the dataset. A 100% coding agreement was reached by reviewing all code applications and discussing each disagreement until consensus by the team of authors was reached.

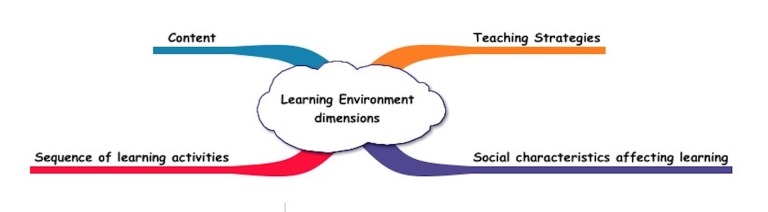

As the responses were converted to codes and as the number of codes increased, the research team renamed and reorganized codes, resulting in a grouping of codes by themes based on the cognitive apprenticeship framework, which has four themes: 1) teaching strategies (e.g., modeling, coaching, scaffolding, articulation, reflection, and exploration) for promoting expertise development; 2) social characteristics affecting learning (e.g., real-world context, practice communities, learner motivation, and cooperation among learners; 3) content required for expertise such as facts, concepts and procedures, and problem-solving, metacognitive, and learning skills; and 4) sequencing of learning activities, thereby increasing complexity and diversity and building global conceptual maps before acquiring specific skills (Figure 1) [10-11].

Figure 1. Cognitive Apprenticeship Framework of the Learning Environment.

Results

The responses by the 30 residents (12 male, 18 female) were separated into a total of 134 answers. Every resident listed a minimum of three answers because they were prompted that way, with most residents stating four or five different ideas. The answers were then grouped into one of 27 different codes (Table 1). None of the codes were deemed to fit into the cognitive apprenticeship framework theme of sequencing.

Table 1. Codes for All Resident Responses Grouped into Teaching Strategies, Social Characteristics, or Content.

ABA: American Board of Anesthesiology

| Code | Total number of times mentioned | CA-1 | CA-2 | CA-3 | |

| Teaching Strategy | Autonomy (step back & let resident work through) | 13 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| Reasoning (explain why attending does things) | 12 | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| Literature (bring articles relevant to the case) | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Flexibility (open to trying different things) | 7 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |

| Prior knowledge (assess the baseline level) | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | |

| Real-time feedback | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Reflection (ask the resident questions) | 6 | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| Teach-back (ask residents to explain what they were taught in own words) | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 | |

| Visualization (use graphs or diagrams) | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Specify learning goals (before the start of the case or the day before) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Discussion (use two-way communication) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Breaking down a complex thing | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Practice techniques in non-pressure environment | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Multimodal teaching | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Real-time teaching | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Link teaching content to ABA exams | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Challenge out of comfort zone | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Social characteristics | Context (teach something relevant to the case) | 8 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Commitment (take time to teach, make effort) | 8 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Psychological safety (be open and approachable to questions from resident) | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Equanimity (remain calm and collected) | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Proper timing for instruction | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Belonging (facilitate communication with OR team) | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Confident clinically | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| Personable and open | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ask for feedback for themselves | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Content | Focus on a few learning points | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 134 | 45 | 46 | 43 |

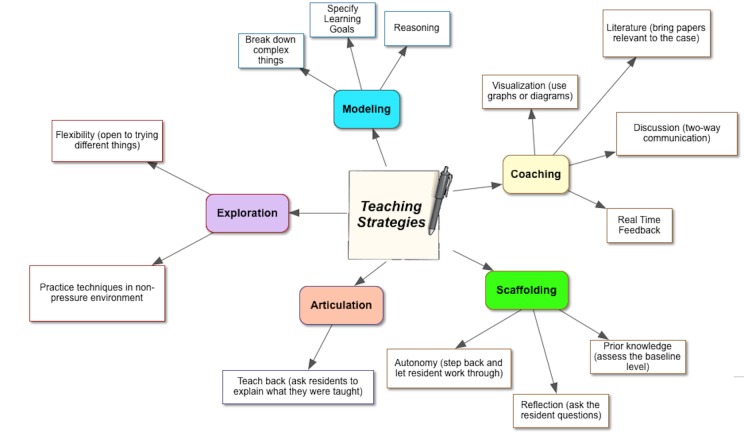

Teaching strategy codes were categorized into different cognitive apprenticeship framework types (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 2. Teaching Strategy Codes with Sample Verbatim Quotes to Illustrate.

| Scaffolding – provide supports to encourage the performance of activities at their learning edge & gradually decrease support over time | |

| Autonomy (step back and let resident work through) |

|

| |

| Prior knowledge (assess the baseline level) |

|

| |

| Reflection (ask the resident questions) |

|

| |

| Modeling – let learner observe you perform the activity, think out loud explicitly demonstrate both physical act & thinking | |

| Reasoning (explain why attending does things ) |

|

| |

| |

| Specify learning goals (before start of case or day before) |

|

| |

| Breaking down a complex thing |

|

| Coaching – observe learner perform the activity and provide directed feedback and guidance | |

| Literature (bring papers relevant to the case) |

|

| Real-time feedback |

|

| |

| Visualization (use graphs or diagrams) |

|

| Discussion (two-way communication) |

|

| Exploration – invite learners to identify and undertake new learning activities or pose and solve their own questions to promote independent learning | |

| Flexibility (open to trying different things) |

|

| |

| Practice techniques in non-pressure environment |

|

| Articulation – ask learners to talk through activity, explain their thinking, and or describe their rationale for approach or decision | |

| Teach back (ask residents to explain what they were taught) |

|

Figure 2. The Teaching Strategies Most Commonly Mentioned by Residents About the Best Faculty Educators.

Verbatim quotes in Table 3 illustrate those codes grouped under social characteristics.

Table 3. Social Characteristics of OR Teaching with Verbatim Quotes.

OR: operating room

| Code | Verbatim quote example |

| Context (teach something relevant to the case) |

|

| |

| Commitment (take time to teach, make an effort) |

|

| |

| Psychological safety (be open and approachable to questions from resident) |

|

| |

| |

| Equanimity (calm and collected) |

|

| |

| Proper timing for instruction |

|

| |

| Belonging (facilitate communication with OR team) |

|

| Confident clinically |

|

| Personable and open |

|

| |

| Ask for feedback for themselves |

|

|

One code derived from the resident interviews, focus on a few learning points, was classified into the content theme (Table 4).

Table 4. Verbatim Quote Examples of Focus on a Few Learning Points.

| Code | Verbatim quote examples |

| Focus on a few learning points |

|

|

Discussion

Phenomenology influences research questions by placing emphasis on a phenomenon to be explored, phrased in terms of a single concept or idea [12]. In this study, the phenomenon of interest is OR teaching, as described via interviews with the anesthesia residents. The results of this study affirm the characteristics of good teaching identified as valuable in adult learning theory and that are useful in the OR. The two behaviors most commonly positively recognized by the residents were: 1) autonomy whereby the attending steps back and lets the resident work through patient care in the OR, and 2) reasoning whereby the attending explains the rationale underlying decisions and actions delivered in the care of the anesthetized patient. Social characteristics were also often singled out by residents and related to teaching in the context of the patient at hand and having the attending show effort and commitment to teaching.

We choose to use the cognitive apprenticeship framework because the novice interacting with the expert helps the novice understand the stages needed to become an expert. In contrast to traditional apprenticeship, cognitive apprenticeship emphasizes that learning considerations, not workplace needs, drive the assignment of learner tasks and problems. Teaching emphasizes the application of knowledge. Anesthesia education in the OR lends itself to this framework because of faculty supervision of the resident aimed at the development of knowledge and skills through OR anesthesia practice.

The residents in this study verbalized examples of three of the four cognitive apprenticeship framework themes (teaching strategies, social characteristics, and content) but not sequencing. Sequencing refers to progressively increasing the complexity and diversity of learning activities. An example might be showing proficiency in a low complexity task (intubating a straightforward airway) before moving to higher complexity airway tasks. Sequencing may be less applicable in the OR because of the short duration of the OR day so there may not be enough time for the attending to increase task complexity during the one day. Sequencing also refers to building global conceptual maps before acquiring specific skills. It is also possible that residents didn’t realize or were able to synthesize that some OR teaching involves sequencing.

Residents spoke about several other social characteristics established by successful teachers in the OR. The residents look favorably on attendings who are easily approachable for asking questions (psychological safety) and communicate well with other staff so that the residents can work smoothly and peacefully in the OR (belonging). Residents further asserted that the best attendings stay calm even during difficult cases, were confident in their ability in the OR so could come to the aid of the resident in any situation, and connected well with the resident on a personal level.

A few residents emphasized that attendings should be mindful of proper timing for teaching so that it occurs when the resident is not occupied with the patient and. therefore, can pay attention to what the attending is communicating. This illustrates cognitive load theory, as it is easy to overwhelm the trainee’s limited working memory capacity because of the cognitive processing required to complete a new task or understand a new concept [13]. In other words, if the resident is placing a central line for the first time, not much of what the attending is saying that is not explicitly related to real-time feedback will be remembered by the resident. Limits to the working memory capacity interfere with learning due to different forms of cognitive loads: intrinsic (the level of difficulty of the problem), germane (learning and development of schema), and extraneous (material not relevant to the problem at hand). The attending can try to reduce cognitive overload by providing germane examples, reducing extraneous load, and breaking down complex problems into smaller components.

Finding the proper timing to teach is a unique challenge in the OR. Some days, the attending may, for example, have one room with an all-day case with some invasive lines and a difficult airway. After the case is underway, the attending may have an opportunity to do some explicit teaching during the surgery. In contrast, if the attending is double-covering with several cases in each of the two rooms, and after getting the residents out for breaks, there may be little time left over to do explicit teaching, at least in some of the ways described by some of the residents in this study. During such challenging days, the faculty may find themselves teaching the residents during induction, which may result in cognitive overload because they are trying to concentrate.

Several high-value teaching strategies that were mentioned by the residents related to coaching. Examples included bringing an article relevant to the case to the OR, using a graph or diagram (visualization) to promote a better understanding of complex ideas, discussion as a form of interactive learning, instead of one-way lecture-style learning; and providing immediate feedback while residents are managing patients or right after they finished a procedure (real-time feedback). Online forms can be used to document this type of feedback [14].

High-performing teaching attendings also support and encourage the performance of activities at the resident’s learning edge and with the attending gradually decreasing support over time. These were grouped under scaffolding and were verbalized by the residents in different ways: assess the resident’s specific knowledge level before embarking on a teaching route, challenge residents out of their comfort zone and help them get through that challenge, and ask the resident questions to make the resident think and reflect.

Other desirable techniques identified by the residents were grouped under articulation. Examples are to ask the resident to explain what they just learned so that the attendings can assess understanding and explore whereby the attending is flexible and open to different plans that are possible and which the resident suggests.

The content dimension of the cognitive apprenticeship framework includes factual, conceptual, and procedural knowledge as well as how to use these kinds of knowledge. This expertise includes facts, concepts, procedures, problem-solving, metacognitive, and learning skills. Several residents mentioned the importance of having the attending focus on a few take-home teaching points and not offering so much content as to risk overwhelming the resident.

This study has several limitations. Being a single-institution study, the results may not be generalizable as a different department with different residents may have valued the attributes of good OR anesthesia teaching differently. Other training programs may have a different culture or learning environment within which trainees function [15]. This environment includes the pressures, stresses, rewards, and any other influences perceived by learners [16]. Although the residents interviewed for this study are exposed to more than 150 attendings, the atmosphere, workload, supervision, structure, and organization of other residencies may be sufficiently different so as to make our results less applicable elsewhere [17].

Interviewing more residents may have yielded more data about OR teaching, but after the first 24 residents were interviewed, the additional final residents did not yield any new codes, suggesting that the major views and experiences on the best teaching characteristics were captured.

Also, not enough residents were studied to see if there were real differences in responses, as residents progress through training. Ascertaining any such differences, such as comparing CA3s versus CA1s was not the goal of this study and may deserve attention in future studies. Also, a different group of investigators may have coded the text of the responses differently. For example, we choose to separate “Commitment (take time to teach, make an effort)” from “Literature (bring papers relevant to the case)” even though if an attending brings an article that would be a sign of commitment. Our reasoning was that the two codes were separate specific behaviors that could be explicitly discussed with faculty desiring to improve their OR teaching.

Another limitation is that it is not known whether the practices identified by the residents actually ultimately result in more proficient residents or in better patient outcomes. Learners may not always have insight into what they need to learn and how best to learn it. In fact, though the residents want a related article to the case only on the spot, they did not mention that they want the attendings to discuss it further the next day or later. This may be especially true for less experienced residents, as they may not be able to perceive the value of learning something that experience has taught the faculty is important. An effective teacher may provide context and support for why the teaching point is important, but a resident may discount this. At the K-12 level, studies show that students often fail to identify good teaching techniques such as, for example, evaluating a charismatic teacher who lectures didactically better than a more subdued teacher that implements active learning principles. In contrast, residents may be more mature and understand what teaching benefits their learning.

In post-graduate medical education, learning occurs through the accumulation and processing of clinical experiences. As residents participate in clinical work, learners have a variety of sources of information, or ‘learning cues,’ that facilitate the interpretation of the experience and the construction of expertise. In this setting, teaching is a multifaceted undertaking [18]. Even though 27 different behaviors and characteristics were identified, none of the 27 was mentioned by more than 13 of the 30 residents interviewed. This suggests that there exists a wide range of activities that go into optimal OR teaching. Leveraging the knowledge of medicine and patients with knowledge of context and pedagogy and learners into teaching scripts can guide the faculty to choose optimal content and teaching interactions [19].

Conclusions

Best practice for OR teaching, as perceived by anesthesia residents, includes social characteristics, such as context, commitment, psychological safety, equanimity, and proper timing, as well as teaching methods, such as autonomy, reasoning, literature, prior knowledge, flexibility, reflection, real-time feedback, and teach back. Further studies can determine if training the anesthesiology faculty to incorporate these elements increases the caliber of daily teaching in the OR.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared financial relationships, which are detailed in the next section.

Jakob Louis Demant Thomsen, MD declare(s) a grant from Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. Although it is not related to the subject of this article, Jakob Louis Demant Thomsen received grants for two investigator-initiated studies from Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Stanford University IRB issued approval None. Reviewed by Tessa Hapanowicz: Based on the information provided in this application, the IRB has determined that this project does not meet the definition of research as defined in 45 CFR 46.102(d), nor the definition of clinical investigation as defined in 21 CFR 50.3(c).

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.Does faculty follow the recommended structure for a new classroom-based, daily formal teaching session for anesthesia residents? Anwar A, Tanaka P, Madsen MV, Macario A. Cureus. 2016;8:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Using an ACTIVE teaching format versus a standard lecture format for increasing resident interaction and knowledge achievement during noon conference: a prospective, controlled study. Sawatsky AP, Berlacher K, Granieri R. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:129. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.How residents learn: qualitative evidence for the pivotal role of clinical activities. Teunissen PW, Scheele F, Scherpbier AJ, van der Vleuten CP, Boor K, van Luijk SJ, van Diemen-Steenvoorde JA. Med Educ. 2007;41:763–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AMEE Guide no. 34: teaching in the clinical environment. Ramani S, Leinster S. Med Teach. 2008;30:347–364. doi: 10.1080/01421590802061613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryson EO. Comprehensive Guide to Education in Anesthesia. New York: Springer Science+Business; 2014. Teaching by Example; pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.An instrument designed for faculty supervision evaluation by anesthesia residents and its psychometric properties. de Oliveira Filho GR, Dal Mago AJ, Garcia JH, Goldschmidt R. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1316–1322. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318182fbdd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resident characterization of better-than- and worse-than-average clinical teaching. Hayder B, Charnin J, Voepel-Lowis T, Baker K. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:120–128. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829b34bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. BMJ. 2000;320:114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins A, Brown JS, Newman S. Knowing, Learning and Instruction: Essays in Honor of Robert Glaser. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New Jersey; 1989. Cognitive Apprenticeship: Teaching the Crafts of Reading, Writing and Mathematics; pp. 453–494. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dennen VP. Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, 2nd ed. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. Cognitive Apprenticeship in Educational Practice Research on Scaffolding, Modeling, Mentoring, and Coaching as Instructional Strategies; pp. 813–828. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creswell JW. California: Sage Publications Inc; 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Cognitive Science of Learning: Concepts and Strategies for the Educator and Learner. Weidman J, Baker K. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:1586–1599. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Implementation of a needs-based online feedback tool for anesthesia residents with subsequent mapping of the feedback to the ACGME milestones. Tanaka P, Merrell SB, Walker K, Zocca J, Scotto L, Bogetz AL, Macario A. Anesth Analg. 2017;124:627–635. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbott: Learning Environment. [Nov;2017 ];Abbott S. Learning. http://edglossary.org/learning-environment/ 2013

- 16.What is medical education here really like? Suggestions for action research studies of climates of medical education environments. Genn JM, Harden RM. Med Teach. 1986;8:111–124. doi: 10.3109/01421598609010737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Development and validation of the Scan of Postgraduate Educational Environment Domains (SPEED): a brief instrument to assess the educational environment in postgraduate medical education. Schönrock-Adema J, Visscher M, Raat AN, Brand PL. PLoS One. 2015;10:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Learning from clinical work: the roles of learning cues and credibility judgements. Watling C, Driessen E, van der Vleuten CP, Lingard L. Med Educ. 2012;46:192–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Excellence in clinical teaching: knowledge transformation and development required. Irby DM. Med Educ. 2014;48:776–784. doi: 10.1111/medu.12507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]