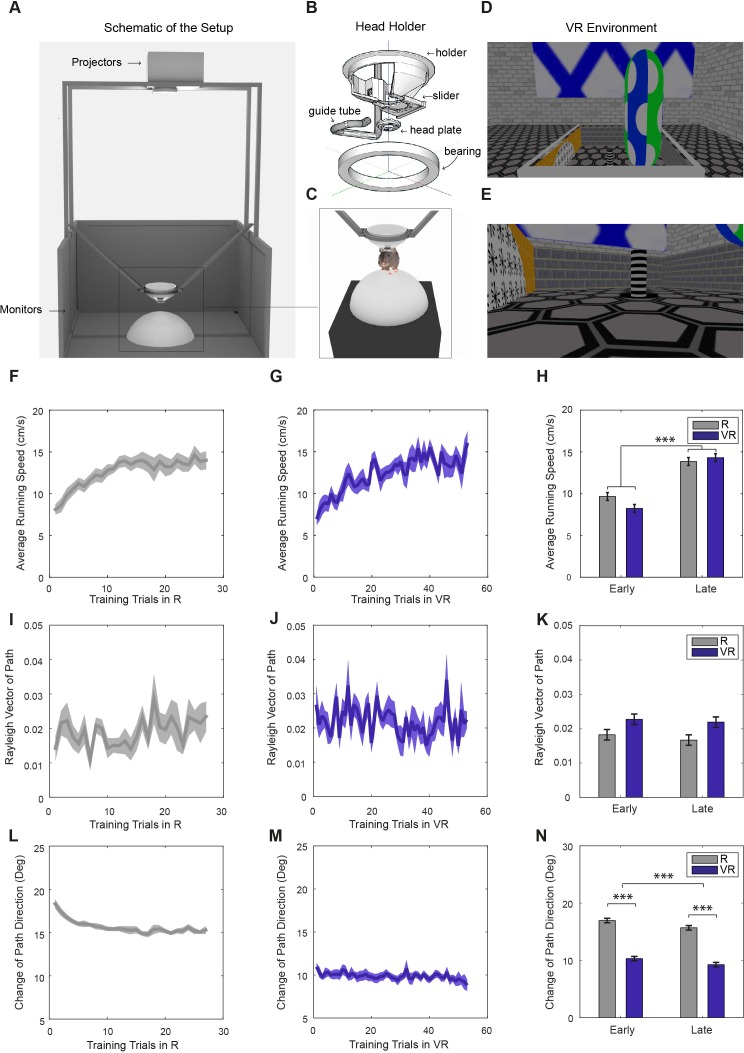

Figure 1. Virtual reality setup and behavior within it.

(A) Schematic of the VR setup (VR square). (B) A rotating head-holder. (C) A mouse attached to the head-holder. (D–E) Side views of the VR environment. (F–G) Average running speeds of all trained mice (n = 11) across training trials in real (‘R’; F) and virtual reality (‘VR’; G) environments in the main experiment. (H) Comparisons of the average running speeds between the first five trials and the last five trials in both VR and R environments, showing a significant increase in both (n = 11, p<0.001, F(1,10)=40.11). (I–J) Average Rayleigh vector lengths of running direction across training trials in R (I) and VR (J). (K) Comparisons of the average Rayleigh vector lengths of running direction between the first five trials and the last five trials in both VR and R. Directionality was marginally higher in VR than in R (n = 11, p=0.053, F(1,10)=4.82) and did not change significantly with experience. (L–M) Average changes of running direction (absolute difference in direction between position samples) across training trials in R (L) and VR (M). (N) Comparisons of the changes of running direction between the first five and last five trials in both R and VR. Animals took straighter paths in VR than R (n = 11, p<0.001, F(1,10)=300.93), and paths became straighter with experience (n = 11, p<0.001, F(1,10)=26.82). Positions were sampled at 2.5 Hz with 400 ms boxcar smoothing in (I–N). All error bars show s.e.m.