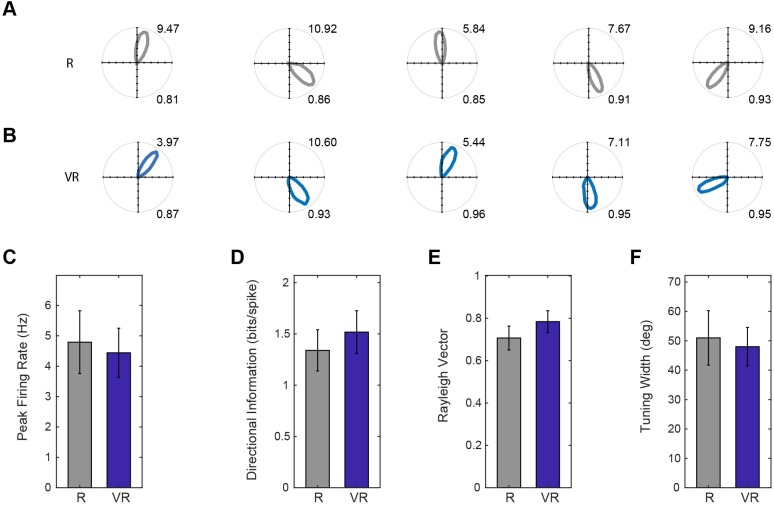

Figure 5. Head direction cell firing in real and virtual environments.

(A–B) Polar plots of the same five HD cells in dmEC simultaneously recorded in R (A) and VR (B, one cell per column). Maximum firing rates are shown top right, Rayleigh vector length bottom right. (C–F) Comparisons of basic properties of HD cells in dmEC between R and VR. There were no significant differences in peak firing rates (t(11)=0.65, p=0.53; (C); directional information (t(11)=1.38, p=0.19; D); Rayleigh vector length (t(11)=1.69, p=0.12; E); and tuning width (t(11)=0.48, p=0.64; F).