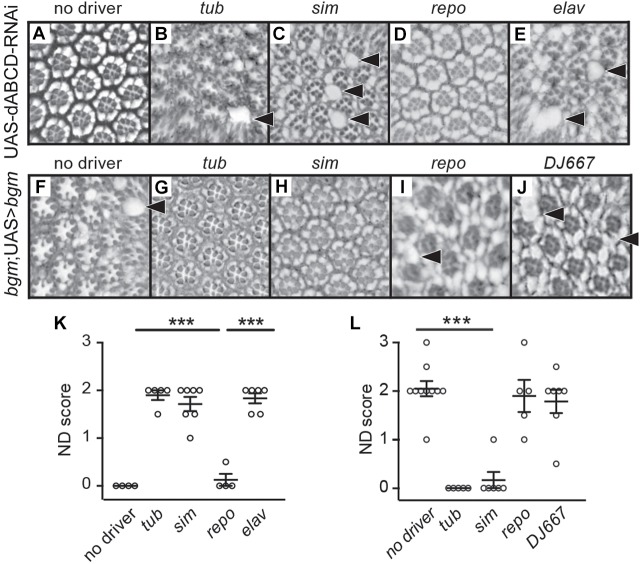

Fig. 1.

dABCD and bgm are required in adult retinal neurons. (A) Retinal cross-sections of UAS-dABCD-RNAi control animals (no Gal4 driver) reveal a highly organized ommatidial structure. (B) In contrast, ubiquitous knockdown of dABCD results in a shared loss-of-function phenotype with bgm and dbb mutants, with holes and disrupted pigment cells between ommatidia. (C,E) Neuronal knockdown of dABCD, but not glial knockdown (D), also leads to neurodegeneration. (F) Representative cross-section of a bgm mutant at day 20 post-eclosion. (G) Ubiquitous expression (tub-Gal4) of an inducible bgm+ transgene rescues neurodegeneration in a bgm mutant background. (H) Driving bgm+ expression in neuronal cells (sim-Gal4) is sufficient to rescue the mutant phenotype; however, (I) driving bgm+ in glial cells (repo-Gal4) does not result in rescue. (J) DJ667-Gal4, which was used as a negative control as it is specifically expressed in flight muscles, fails to rescue. (K) Blinded quantification of neurodegenerative (ND) phenotypes in A-E. (L) Blinded quantification of neurodegenerative phenotype seen in G-J. In K and L, scores were compared by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's test and P-values. Data points represent biological replicates and are presented with means±s.e.m. ***P<0.001. Arrowheads point to areas of retinal degeneration.