Abstract

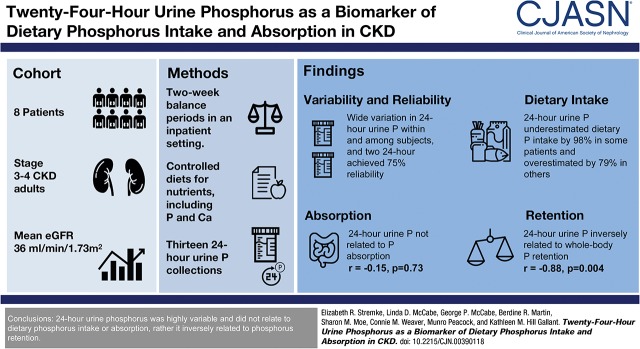

Background and objectives

Twenty-four-hour urine phosphorus is commonly used as a surrogate measure for phosphorus intake and absorption in research studies, but its reliability and accuracy are unproven in health or CKD. This secondary analysis sought to determine the reliability and accuracy of 24-hour urine phosphorus as a biomarker of phosphorus intake and absorption in moderate CKD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Eight patients with stage 3–4 CKD participated in 2-week balance studies with tightly controlled phosphorus and calcium intakes. Thirteen 24-hour urine collections per patient were analyzed for variability and reliability of 24-hour urine phosphorus and phosphorus-to-creatinine ratio. The accuracy of 24-hour urine phosphorus to predict phosphorus intake was determined using a published equation. The relationships of 24-hour urine phosphorus with phosphorus intake, net absorption, and retention were determined.

Results

There was wide day-to-day variation in 24-hour urine phosphorus within and among subjects (coefficient of variation of 30% and 37%, respectively). Two 24-hour urine measures were needed to achieve ≥75% reliability. Estimating dietary phosphorus intake from a single 24-hour urine resulted in underestimation up to 98% in some patients and overestimation up to 79% in others. Twenty-four-hour urine phosphorus negatively correlated with whole-body retention but was not related to net absorption.

Conclusions

From a sample of eight patients with moderate CKD on a tightly controlled dietary intake, 24-hour urine phosphorus was highly variable and did not relate to dietary phosphorus intake or absorption, rather it inversely related to phosphorus retention.

Keywords: Biological Phenomena; Biomarkers; calcium; chronic kidney disease; creatinine; Humans; nutrition; Phosphorus; Phosphorus Absorption; Phosphorus, Dietary; Physiological Phenomena; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Reproducibility of Results; Urine Specimen Collection

Introduction

Dietary phosphorus intake in the United States is high, due to both the natural abundance of phosphorus in foods and the use phosphate-containing food additives (1,2). Average intakes of phosphorus in healthy adults (3,4) and adults with CKD (5) well exceed 700 mg/d, the recommended dietary allowance for adults ≥19 years old (6). Phosphorus excess is central to the development and progression of CKD-mineral bone disorder, which is associated with higher fracture, cardiovascular, and mortality risk (7,8). Many existing and emerging therapies aim to reduce phosphorus absorption via phosphorus intake restriction, binding luminal phosphorus, or direct inhibition of intestinal phosphate transporters. Accurate and reliable assessment of phosphorus intake is needed, but this is complicated by limitations in the tools available (9). These limitations include the nutrient databases, which are incomplete and often inaccurate for phosphorus. Differences between phosphorus content determined by nutrient database versus direct chemical analysis of foods show that databases can drastically underestimate phosphorus content of foods (approximately 15%–70%) (10–16).

Twenty-four-hour urine phosphorus is considered a good surrogate of phosphorus intake in healthy adults in phosphorus balance because net phosphorus absorption is efficient and is linearly related to intake over a wide range of intakes (6). This relationship has been assumed to also apply to patients with CKD (17,18) but has not been tested. In CKD, factors other than intake and absorption may affect 24-hour urine phosphorus excretion, including the rate of net bone and tissue retention and volume status (19). Although 24-hour urine phosphorus is indisputably useful as a biomarker of absorption in clinical trials with interventions that have a known mechanism to increase or decrease intestinal absorption (i.e., in a randomized, controlled trial where the intervention is expected to be the cause for effects observed) (20), its reliability and accuracy as a biomarker of phosphorus intake or absorption in observational (associational) studies are unknown. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine the variability and reliability of 24-hour urine phosphorus and its accuracy as a measure of phosphorus intake and absorption in patients with moderate CKD, using data from a previously conducted calcium and phosphorus balance study where phosphorus intake was tightly controlled and precisely measured (21).

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

Data for this secondary analysis were obtained from a previously conducted, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of the effects of calcium carbonate on calcium and phosphorus balance in eight patients with stage 3–4 CKD (Clinicaltrials.gov identification NCT01161407). Detailed methods and results for the parent study are described elsewhere (21) and in the Supplemental Material. Briefly, the parent study consisted of a 2-week run-in where all subjects were given 400 IU/d of cholecalciferol, followed by two 3-week study periods separated by a 3-week washout period. Each 3-week study period included a 1-week outpatient equilibration period to the controlled diet and assigned treatment, followed by 2 weeks of balance measures in a controlled inpatient setting. Treatment was calcium carbonate given in capsule form three times a day with meals or placebo. This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Purdue University and Indiana University Institutional Review Boards. Informed consent was obtained during the parent study.

Twenty-Four-Hour Urine Phosphorus, Urine Phosphorus-to-Creatinine Ratio, and Dietary Phosphorus Intake

During these balance studies, 24-hour urine and feces were collected to calculate calcium and phosphorus balance, which were previously reported (21). Twenty-four-hour urine phosphorus was measured by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (Optima 4300DV; Perkin Elmer; percent coefficient of variation [%CV]=2.4), 24-hour urine creatinine excretion was measured by colorimetric assay using a COBAS MIRA clinical analyzer (Roche Diagnostic, Indianapolis, IN; %CV=2.5), and 24-hour urine phosphorus-to-creatinine ratio was calculated. Whole-body phosphorus balance was calculated as daily intake minus fecal and urine excretion averaged over the entire balance period. Net phosphorus absorption was calculated as daily intake minus fecal excretion averaged over the entire balance period. Intake was controlled, with menus designed by a registered dietitian and prepared in a metabolic kitchen. Phosphorus intake from the controlled 4-day cycle menu was 1564±52 mg/d, calcium was 957±23 mg/d, and sodium was 2749±541 mg/d (menu details provided in the supplemental material in Hill et al. [21]). Mineral content of the controlled diets was analyzed from ashed, homogenized diet composites by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry. “Bone balance” was determined from full kinetic modeling of oral and intravenous 45calcium tracers and reflects a late turnover calcium pool that is generally regarded as bone turnover, but that does not distinguish from potential extraskeletal calcification. Fasting serum and urine biochemistries were obtained at four time-points during the study: baseline, end of the diet equilibration week, and the end of each week of balance (i.e., four measures over 3 weeks, each a week apart). eGFR was calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation (22). Intact fibroblast growth factor 23 (iFGF23) was measured by ELISA (Kainos Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) and intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) was measured by immunoradiometric assay (N-tact; Diasorin, Stillwater, MN). Serum phosphate and creatinine were measured by colorimetric assay using a COBAS MIRA clinical analyzer (Roche Diagnostic). A poorly absorbable fecal marker (polyethylene glycol [PEG], molecular weight 3500) was given 3g per day to assess fecal collection adherence and to calculate daily fecal calcium-to-polyethylene glycol (Ca:PEG) and phosphorus-to-polyethylene glycol ratios (P:PEG), reflective of daily net absorption, and used to indicate achievement of steady state for balance measures (23–25).

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), and statistical significance was set at α=0.05. Descriptive statistics were performed for variability in 24-hour urine phosphorus, phosphorus intake, and 24-hour urine phosphorus-to-creatinine. Within-subject variation was determined from the 13 consecutive days of data during the balance periods. Among-subject variation was determined using average values for each subject over the 13 days of data. These data were complete for all subjects. SDs and %CVs were calculated and are reported to describe the variation (Supplemental Material). For 24-hour urine phosphorus and 24-hour urine phosphorus-to-creatinine, reliability, the correlation between two replicates on the same individual (i.e., the consistency of a measure), was estimated by the intraclass correlation coefficient. The Spearman–Brown prediction formula (26) was used to calculate reliability for the average of different numbers of replicates and to determine the number of replicates needed to achieve a reliability of at least 75% (Supplemental Material). Linear regression was used to determine correlations with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for whole-body phosphorus retention, bone balance (from calcium kinetics), and net phosphorus absorption with 24-hour urine phosphorus.

To assess the accuracy of 24-hour urine phosphorus as an indicator of dietary phosphorus intake, we calculated an estimated phosphorus intake from each daily 24-hour urine phosphorus using the published equation of Lemann (27) (Purine[mmol/d]=1.73+0.512×Pintake[mmol/d]), where P indicates phosphorus, as referenced in the Institute of Medicine Dietary Reference Intakes report on phosphorus (6). These calculated values were compared with the actual phosphorus intake values measured in the ashed, homogenized diet composites from the balance study, and percentage of over- or underestimation are reported. Variation around the mean of calculated intake was expressed in SDs and %CV.

We performed similar analyses for 24-hour urine calcium and calcium-to-creatinine ratio, fecal phosphorus and calcium, and fecal P:PEG and Ca:PEG ratios to describe the variability and reliability of these measures within and among subjects. Analyses were performed on data from both the placebo and calcium carbonate, but results were similar and calcium carbonate did not affect the level of variation observed in 24-hour urine phosphorus. Results from analyses on data from the placebo balance period on all patients are reported here.

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Steady State

Baseline characteristics are given in Table 1. After the 1-week equilibration period to the controlled diet, both fecal Ca:PEG and fecal P:PEG became consistent (i.e., showed no directional trend), indicating that patients had achieved steady state for calcium and phosphorus balance measures (Supplemental Figure 1, A and B) (23,24).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

| Characteristica | Value |

|---|---|

| Women, n/total | 2/8 |

| Black, n/total | 5/8 |

| Diabetes, n/total | 6/8 |

| Hypertension, n/total | 8/8 |

| Age, yr | 59±7 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 38.7±8.7 |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 36±9 |

| Serum calcium, mg/dl | 9.6±0.3 |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl | 3.8±0.6 |

| Serum parathyroid hormone, pg/ml | 85±59 |

| Serum intact FGF23, pg/ml | 79±40 |

FGF23, fibroblast growth factor 23.

Values are mean±SD unless otherwise noted.

Variation in 24-Hour Urine Phosphorus, Urine Creatinine, and Urine Phosphorus-to-Creatinine Ratio

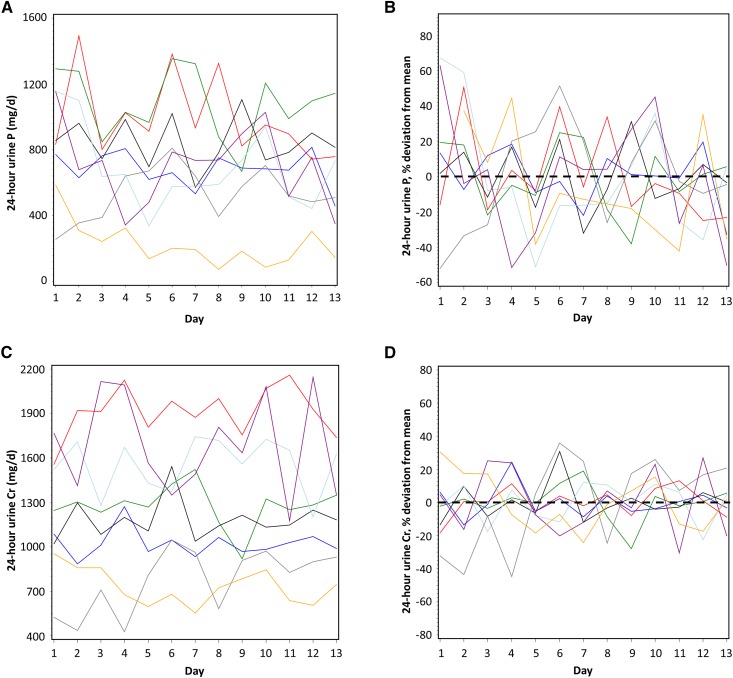

Wide within- and among-subject variation in 24-hour urine phosphorus was observed. SDs within subjects averaged 186 mg/d and ranged from 105 to 248 mg/d (%CV=30, range 15%–60%) and SD among subjects was 268 mg/d (%CV=37) (Figure 1, A and B, Table 2). Despite close monitoring by clinical research center staff, average SD within subjects for urine creatinine was 174 mg/d (range 94–337 mg/d; %CV=15, range 9%–28%) (Figure 1, C and D, Table 2). Among-subject SD for urine creatinine was 427 mg/d (%CV=34), reflecting the range in body size and eGFR. The variation in 24-hour urine phosphorus-to-creatinine ratio (%CV=27, range 12%–51%) was similar compared with 24-hour urine phosphorus (Figure 1, E and F, Table 2). Within-subject variation in eGFR taken from four time-points throughout the study was mean CV=10% (range 2%–37%), and among-subject variation was CV=16% (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Twenty four-hour urine phosphorus was highly variable within and among patients with CKD. Daily variation in subjects in (A) 24-hour urine phosphorus (absolute values) and (B) 24-hour urine phosphorus (% variation above and below the 13-day mean [set at zero] for each subject); (C) 24-hour urine creatinine (absolute values) and (D) 24-hour urine creatinine (% variation above and below the 13-day mean [set at zero] for each subject); (E) 24-hour urine phosphorus-to-creatinine ratio (absolute values) and (F) 24-hour urine phosphorus-to-creatinine (% variation above and below the 13-day-mean [set at zero] for each subject); and (G) predicted dietary phosphorus intake calculated on the basis of 24-hour urine phosphorus (see Materials and Methods). In (G), the measured, controlled level of phosphorus intake is shown by the horizontal black line. In (B, D, and F), the mean for each subject is set at zero and the % fluctuation each day above or below the mean is shown; zero is indicated by a horizontal black dashed line. In all panels, different color lines represent individual subjects. Cr, creatinine; P, phosphorus; P/Cr, phosphorus-to-creatinine.

Table 2.

Within- and among-subject variability in phosphorus and creatinine measures

| Subject | 24-h Urine Phosphorus, mg/da | 24-h Urine Creatinine, mg/da | 24-h Urine Phosphorus-to-Creatinine, mg/mga | Phosphorus Balance, mg/db | Net Phosphorus Absorption, mg/db | %Net Phosphorus Absorptionb | Serum Phosphorus, mg/dlc | Serum Creatinine, mg/dlc | eGFR, ml/minc | Serum iPTH, pg/ml | Serum iFGF23, pg/ml |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within Subjects | |||||||||||

| Subject 1 | 991 (248) | 1911 (168) | 0.52 (0.12) | −260 | 731 | 47 | 3.8 (0.3) | 3.0 (0.1) | 29 (0.6) | 143 (55) | 74 (12) |

| 25% | 9% | 23% | 8.4% | 2.3% | 2% | 39% | 16% | ||||

| Subject 2 | 682 (105) | 1023 (94) | 0.67 (0.08) | −229 | 452 | 29 | 3.8 (0.4) | 1.9 (0.1) | 34 (3) | 47 (10) | 101 (6) |

| 15% | 9% | 12% | 9.6% | 7.4% | 10% | 27% | 5% | ||||

| Subject 3 | 1083 (209) | 1277 (140) | 0.84 (0.10) | −231 | 845 | 54 | 4.0 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.1) | 37 (2) | 60 (10) | 135 (8) |

| 19% | 11% | 12% | 13.1% | 5.0% | 7% | 15% | 18% | ||||

| Subject 4 | 843 (127) | 1180 (135) | 0.71 (0.10) | 82 | 925 | 59 | 4.0 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.2) | 31 (4) | 72 (9) | 62 (28) |

| 17% | 11% | 13% | 13.4% | 10.0% | 11% | 14% | 50% | ||||

| Subject 5 | 693 (243) | 1555 (182) | 0.44 (0.14) | 181 | 872 | 53 | 3.6 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.05) | 41 (1) | 59 (4) | 50 (23) |

| 35% | 12% | 32% | 14.5% | 2.9% | 2% | 10% | 31% | ||||

| Subject 6 | 535 (158) | 771 (215) | 0.69 (0.26) | 344 | 901 | 63 | 3.2 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.1) | 41 (3) | 51 (11) | 74 (14) |

| 30% | 28% | 38% | 15.2% | 7.0% | 7% | 22% | 20% | ||||

| Subject 7 | 708 (241) | 1691 (337) | 0.43 (0.14) | 203 | 923 | 60 | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.4 (0.9) | 26 (9) | 64 (10) | 62 (26) |

| 34% | 20% | 32% | 34.1% | 25.9% | 37% | 23% | 50% | ||||

| Subject 8 | 225 (136) | 731 (123) | 0.31 (0.15) | 680 | 903 | 60 | 3.8 (0.3) | 1.9 (0.1) | 30 (1) | 44 (9) | 61 (15) |

| 60% | 17% | 51% | 6.8% | 3.2% | 5% | 30% | 36% | ||||

| Among subjects | |||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 720 (268) | 1268 (427) | 0.58 (0.18) | 96 (330) | 819 (161) | 53 (11) | 3.7 (0.3) | 2.1 (0.7) | 34 (5) | 67 (32) | 77 (28) |

| %CV | 37 | 34 | 31 | 343 | 20 | 21 | 7 | 33 | 16 | 47 | 36 |

iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; iFGF23, intact fibroblast growth factor 23; %CV, percent coefficient of variation.

Values for each subject are mean (SD) and %CV of 13 days of values in that individual for 24-hour urine phosphorus, 24-hour urine creatinine, 24-hour urine phosphorus-to-creatinine, and predicted phosphorus intake from daily 24-hour urine phosphorus values.

Single values of phosphorus balance, net phosphorus absorption, and %net phosphorus absorption are presented for each subject, calculated using data from the entire balance period.

Values for serum phosphorus, creatinine, eGFR, iPTH, and iFGF23 are mean (SD) and %CV of four values in that individual taken at baseline, end of the 1 week equilibration period to the diet, and at the end of each week of the balance period (i.e., four values over 3 weeks, in 1-week intervals). eGFR was calculated with the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation (22).

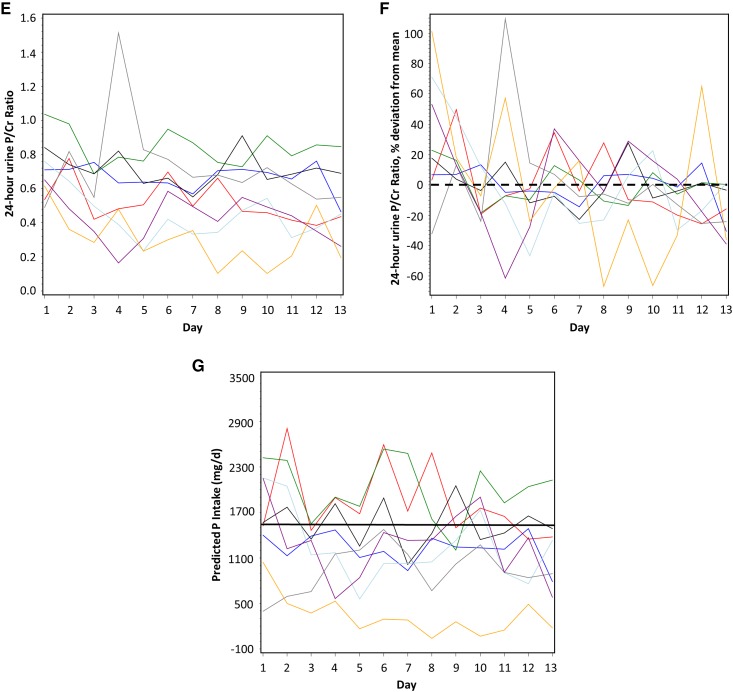

Reliability of 24-Hour Urine Phosphorus and Phosphorus-to-Creatinine Measures

The variation in 24-hour urine phosphorus and phosphorus-to-creatinine was used to determine the number of 24-hour replicates needed to obtain a reliable measure. The intraclass correlation coefficient for 24-hour urine phosphorus was rho=0.65 (95% CI, 0.42 to 0.89), and for phosphorus-to-creatinine was rho=0.60 (95% CI, 0.36 to 0.87). From these values, the number of replicates needed for ≥75% reliability for 24-hour urine phosphorus or phosphorus-to-creatinine was 2 (95% CI, 1 to 5), and more replicates were needed for a greater degree of reliability (Figure 2, A and B).

Figure 2.

At least two 24-hour urine collections were needed for a reliable measure of 24-hour urine phosphorus or phosphorus-to-creatinine ratio. Reliability of (A) 24-hour urine phosphorus and (B) 24-hour urine phosphorus-to-creatinine. n is the number of 24-hour urine collections needed to achieve various levels of reliability. The solid line represents the estimated reliability with n samples, and 95% CIs around this estimate is indicated by dashed lines. Reliability is affected by the variability of the measure and is the extent to which a measurement is predicted to give the same result when repeated. P, phosphorus; P/Cr, phosphorus-to-creatinine.

Accuracy of 24-Hour Urine Phosphorus in Predicting Dietary Phosphorus Intake

A published equation (6,27) was used to determine the accuracy of 24-hour urine phosphorus to predict dietary phosphorus intake. Predicted intakes from this equation both underestimated and overestimated the known phosphorus intake by as much as 98% and 79%, respectively (explained solely by the variation in 24-hour urine phosphorus, as the only variable entered into this equation). The lowest predicted phosphorus intake was <40 mg/d, and the highest was >2800 mg/d (Figure 1G).

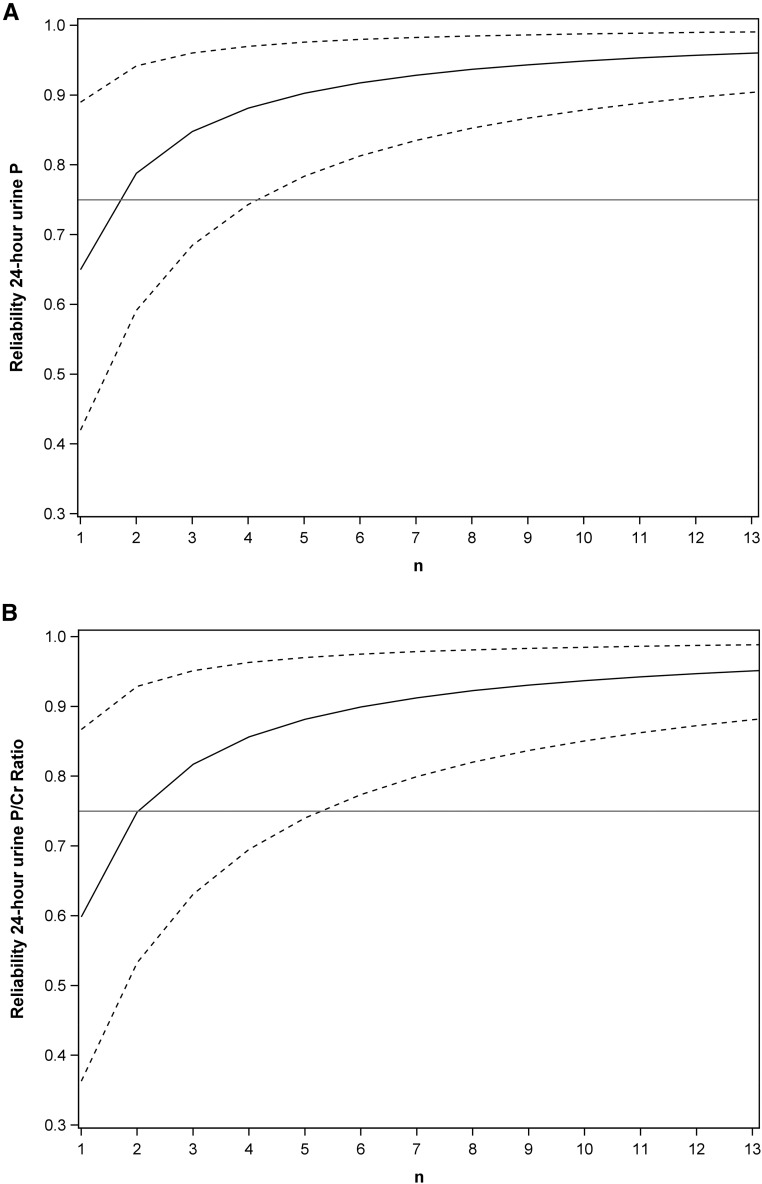

Correlations with 24-Hour Urine Phosphorus and Other Related Measures

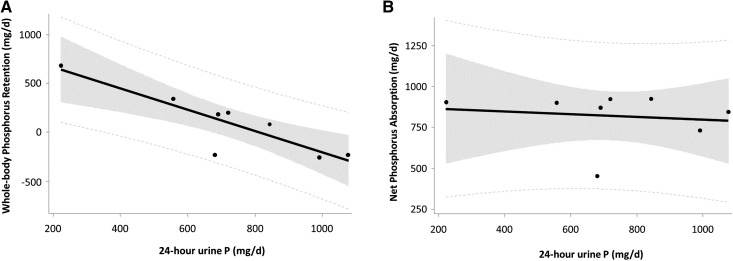

The relationships between mean 24-hour urine phosphorus for each subject and net phosphorus absorption, fecal phosphorus, whole-body phosphorus retention (i.e., phosphorus balance), bone balance (from calcium kinetics), serum iPTH, and serum iFGF23 were determined. Twenty-four-hour urine phosphorus was highly negatively correlated with whole-body phosphorus retention (r=−0.88, P=0.004; Figure 3A, Table 2) and with bone balance from calcium kinetics (r=−0.84, P=0.009). There were no statistically significant correlations with net phosphorus absorption (r=−0.15, P=0.73; Figure 3B, Table 2), fecal phosphorus (r=0.28, P=0.51), serum iPTH (r=0.55, P=0.16), or serum iFGF23 (r=0.53, P=0.18), although the small sample size may be limiting power to detect these relationships.

Figure 3.

Twenty four-hour urine phosphorus did not relate to net phosphorus absorption, but negatively related to whole-body phosphorus retention in CKD patients. Correlations between (A) 24-hour urine phosphorus and whole-body phosphorus retention and (B) 24-hour urine phosphorus and net phosphorus absorption. The solid line is the regression fit, the shaded area shows the 95% confidence limits, and the dotted lines indicate the 95% prediction limits. The regression equation for (A) is: Retention (mg/d)=833–1.088×(24-hour urine phosphorus, mg/d). Note that this equation could be used to estimate phosphorus retention from 24-hour urine phosphorus (ideally two or more replicates) with the caveat that subjects are consuming a similar phosphorus intake of approximately 1500 mg/d as those in this study. P, phosphorus.

The wide day-to-day variation within individuals was also investigated further. Twenty-four-hour urine phosphorus was again negatively associated with whole-body phosphorus retention (partial r=−0.29, P=0.001), and not related to daily net phosphorus absorption or fecal P:PEG. However, greater urine volume was related to greater 24-hour urine phosphorus (partial r=0.46, P<0.001).

Variation and Reliability of 24-Hour Urine Calcium and 24-Hour Urine Calcium-to-Creatinine Ratio Measures

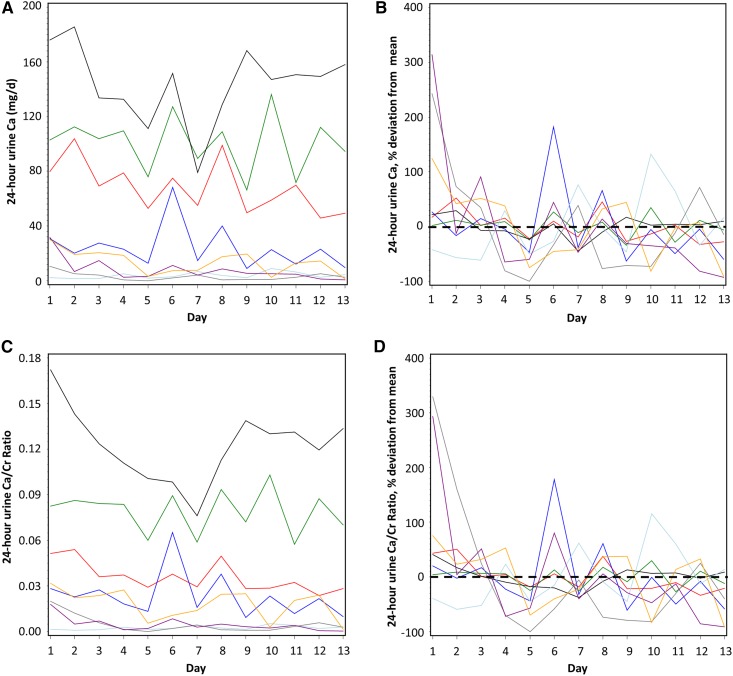

Twenty-four-hour urine calcium, which was very low in these patients and did not increase even when given an additional 1500 mg/d calcium from calcium carbonate, as previously reported (21), did not relate to measures of whole-body calcium retention (r=−0.28, P=0.51), net calcium absorption (r=−0.02, P=0.96), fecal calcium excretion (r=−0.06, P=0.89), or bone balance (r=−0.47, P=0.24). Wide within- and among-subject variation in 24-hour urine calcium was observed, but this must be interpreted in the context of very low mean 24-hour urine calcium output in most of these patients (in contrast to 24-hour urine phosphorus) (Figure 4, A–D). SDs within subjects averaged 13 mg/d and ranged from 2 to 28 mg/d (%CV=58, range 19%–107%) and SDs among subjects averaged 53 mg/d (%CV=116). The variation in 24-hour urine calcium-to-creatinine within subjects averaged 0.01 and ranged from 0.001 to 0.02 (%CV=57, range 18%–120%) and among subjects averaged 0.04 (%CV=85%). The intraclass correlation coefficient for 24-hour urine calcium was rho=0.92 (95% CI, 0.82 to 0.98), and for calcium-to-creatinine was rho=0.92 (95% CI, 0.83 to 0.98). Thus, the number of replicates needed for ≥75% reliability for 24-hour urine calcium or urine calcium-to-creatinine was only one.

Figure 4.

Twenty four-hour urine calcium was generally low and showed high percent coefficients of variation, but low absolute variation in CKD patients. Daily variation in subjects in (A) 24-hour urine calcium (absolute values) and (B) 24-hour urine calcium (% variation above and below the mean [set at zero] for each subject); (C) 24-hour urine calcium-to-creatinine ratio (absolute values) and (D) 24-hour urine calcium-to-creatinine (% variation above and below the mean [set at zero] for each subject). In (B and D), the mean for each subject is set at zero and the percentage fluctuation each day above or below the mean is shown; zero is indicated by a horizontal black dashed line. In all panels, different color lines represent individual subjects. Ca, calcium; Ca/Cr, calcium-to-creatinine.

Discussion

The results of this study show that 24-hour urine phosphorus is a highly variable measurement, even under optimal clinical research center conditions for complete and timed collections, and that repeated measurements are necessary when a reliable value is needed. The variability in a less-controlled outpatient setting would almost certainly be higher. Twenty-four-hour urine creatinine was also variable day-to-day within subjects in this controlled setting. This could potentially indicate a lack of steady state in creatinine metabolism. However, if this were the case, one would expect to see a trend in values. Instead, we saw random fluctuation, indicating this was random variation produced by biologic and/or methodological factors. There have been reports of tighter variation in day-to-day 24-hour urine creatinine excretion in healthy adults (28), but there have also been reports of similar variation in healthy adults (29–31) compared with the patients with moderate CKD in this study. Healthy adolescents have shown even greater day-to-day variation in a controlled research setting (32). A study of patients with diabetic nephropathy showed similar random day-to-day variation in 24-hour urine creatinine compared with our study as well (%CV=27.7%) (33). Some of the variation in within-individual 24-hour urine phosphorus and urine creatinine may be, in part, due to variation in complete urinary tract and bladder emptying. However, correcting for urine creatinine did not lessen the within-subject variation in 24-hour urine phosphorus, as shown by the similar extent of variation in 24-hour urine phosphorus-to-creatinine as 24-hour urine phosphorus. Another possibility to explain this variation is day-to-day fluctuations of GFR. Data on daily GFR in these subjects was not available over the 13 days. However, eGFR was determined in each patient using morning fasting serum creatinine values at four time-points during the study. The mean %CV in eGFR observed in our study was similar in extent to the mean CV of 13.8% for GFR (measured directly by iothalamate clearance) reported in a subset of participants in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (34). Caloric consumption was controlled day-to-day for each patient, and patients had high adherence to their study diets, so this is likely not a source of variation in either 24-hour urine phosphorus or urine creatinine. Body weights were also stable over the study. Daily fluctuations in BP may contribute to variation in urine flow and thus solute excretion (33,35). Although the total amount of dietary phosphorus was controlled day to day, the potential differences in the relative bioavailability of phosphorus from various food sources could have contributed to the variation observed. However, if this were the case, we would expect to have seen a pattern of association between 24-hour urine phosphorus excretion and the cycle menu day, which we did not. Methodological errors are always potential contributors to variation, including incomplete, poorly timed, or inaccurately portioned collections. However, we have no reason to suspect these played large roles in our study because of protocols that were in place to minimize these errors.

We show that the average of at least two 24-hour urine phosphorus measures are required for a reliable measure with at least 75% reliability. Although 75% is generally considered a threshold for an acceptable level of reliability (26), the 13 replicates that were available from these balance studies gave >90% reliability for both 24-hour urine phosphorus and phosphorus-to-creatinine. However, the wide variation in the 13-day mean 24-hour urine phosphorus among subjects (Table 2) indicates that even a reliable measurement of 24-hour urine phosphorus could lead to erroneous inferences regarding phosphorus intake and absorption. To illustrate this point, we show both the large overestimation and underestimation of dietary phosphorus intake possible when calculated on the basis of 24-hour urine phosphorus, using a published equation (6,27). Thus, our results show that for an individual patient, 24-hour urine phosphorus was not reflective of actual phosphorus intake despite a relatively high correlation (r=0.88) between 24-hour urine phosphorus and intake reported in the literature across pooled studies of the general population (27). Recently, large among-subject variation in 24-hour urine phosphorus was also reported in a study of eight young healthy Japanese men on a fixed phosphorus diet (1138 mg/d) over 5 days of 24-hour urine collections (36), which corroborates our findings.

Similar variability has been reported for 24-hour urine sodium collections in healthy individuals in a controlled environment, in part due to oscillatory secretion of mineralocorticoid that did not align to a 24-hour day and excretion of other solutes that might affect urinary osmolarity and thus sodium excretion (37). A similar phenomenon may occur with urinary phosphorus excretion which is affected by GFR, urine volume, sodium reabsorption, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), and cacitriol. Indeed, the relationship within subjects between higher 24-hour urine phosphorus and greater urine volume suggests that this variation may be because of daily variation in GFR; however, we did not have daily GFR data from this study to confirm this hypothesis. There is also diurnal variation in urinary phosphorus excretion (38). Furthermore, after an acute oral phosphorus load, PTH rises after 8 hours, FGF23 rises after 12 hours, and calcitriol decreases at 36 hours. Thus, it is likely that fluxes in these hormones do not adhere to a 24-hour clock, resulting in variability of phosphorus excretion (39). We were limited by the number of sampling time-points available to assess the relationship among 24-hour urine phosphorus excretion and diurnal and day-to-day variation in FGF23 or PTH.

Our results also suggest that differences in whole-body phosphorus retention, not differences in intestinal phosphorus absorption, were responsible for the wide variation observed among these eight patients consuming the same fixed level of dietary phosphorus. This may be due to differences in bone remodeling, extraskeletal tissue uptake, or kidney efficiency for phosphate excretion. Indeed, the patient with the lowest average 24-hour urine phosphorus (225 mg/d) had a net phosphorus absorption of 903 mg/d (60% of intake), and the highest value for whole-body phosphorus retention (680 mg/d). Conversely, the patient with the highest average 24-hour urine phosphorus (1083 mg/d) had a similar level of net phosphorus absorption (845 mg/d; 54% of intake), but negative whole-body phosphorus retention (−231 mg/d) (Table 2). Solely on the basis of 24-hour urine phosphorus, one would have concluded that the former patient had very low phosphorus intake and/or absorption and the latter had very high phosphorus intake and/or absorption. Neither conclusion would have been correct. Importantly, serum phosphorus did not relate to whole-body phosphorus balance (Table 2) (21). Within subjects, 24-hour urine phosphorus was also negatively associated with whole-body phosphorus balance and not net phosphorus absorption. These results are corroborated by a recently published study by Turner et al. (40), showing reduced urinary phosphorus excretion in adenine-induced CKD rats compared with healthy rats, which was not associated with a reduction in dietary phosphorus absorption, assessed by oral gavage of P-33 tracer. Turner et al. argue similarly that tissue retention, not impaired absorption, was responsible for the lower urine phosphorus values seen in CKD.

These results provide an alternative explanation for unexpected associations with 24-hour urine phosphorus in patients with CKD in the literature. For example, Palomino et al. (17) showed that higher 24-hour urine phosphorus was associated with lower, not higher, risk of cardiovascular events. Similarly, a post-hoc analysis of MDRD study data (41) showed that 24-hour urine phosphorus was not related to averse outcomes in patients with CKD, which was counter to the hypothesis using 24-hour urine phosphorus as a proxy of phosphorus intake/absorption. If higher 24-hour urine phosphorus is indicative of lower phosphorus retention rather than higher phosphorus intake/absorption, then inverse relationships are expected rather than surprising.

Importantly, the results presented here underscore an important and underappreciated facet to the results from our primary article from these balance studies (21): the range in absolute phosphorus balance values among these eight patients. The primary study was designed to evaluate the effect of a calcium-based phosphate binder on calcium and phosphorus balance. As such, mean and SEM were reported, indicating phosphorus balance was neutral on average and was not affected by the calcium-based phosphate binder. Here, we show that these eight patients spanned a wide range from negative to positive phosphorus balance values. Balance data from a larger sample of patients are needed to determine a “true” range in phosphorus balance in this population.

Compared with 24-hour urine phosphorus, 24-hour urine calcium also showed high %CV values; however, this was mainly due to the very low mean 24-hour urine calcium output in most of these patients. Thus, this was not particularly meaningful variation (for instance, when mean 24-hour urine calcium excretion is 8 mg/d with an SD of 8 mg/d and 100% CV). Therefore, it is not surprising that 24-hour urine calcium did not relate to net calcium absorption or whole-body calcium balance. This presents a challenge in assessing calcium load, absorption, or retention in patients with CKD, as neither urinary calcium nor serum calcium are appropriate biomarkers for intake or absorption (21,42). At present, the most useful and clinically available assessment of calcium load may be a careful evaluation of calcium intake from dietary, supplemental, and pharmacologic sources (43).

Day-to-day fecal phosphorus and calcium excretion was highly variable within individuals (Supplemental Material). Adjustment for fecal PEG output greatly reduced the variability and thus improved the reliability for fecal calcium and phosphorus, expressed as an mg:mg ratio with fecal PEG. After a 1-week diet equilibration period, two and six replicates are needed for ≥75% reliability in fecal P:PEG and Ca:PEG, respectively. Fecal PEG adjustments can overcorrect for mineral excretion (23), as there is some variation among individuals for intestinal PEG (molecular weight 3350) absorption (44). Thus, for longer balance periods (e.g., 2 weeks or longer), unadjusted fecal calcium and phosphorus values averaged over the balance period may be preferable for use in balance equations, and fecal Ca:PEG and P:PEG ratios used only for assessment of steady state and fecal PEG percentage recovery as an indicator of adherence (e.g., >80% recovery considered as high adherence). However, for studies with shorter balance periods (e.g., 48-hour studies), PEG adjustment would be highly preferable to the alternative of no adjustment. In these cases, we recommend that authors report unadjusted milligrams per day of fecal calcium and/or phosphorus, along with a PEG-adjusted value to be used in balance calculations, representing the amount of oral PEG administered per day (e.g., milligram fecal phosphorus per 3 g fecal PEG recovery). It is important to emphasize the need for an adequate diet equilibration period of ≥1 week that includes oral PEG administration before balance measurements.

Strengths of our study include the well controlled diet and 2-week balance study in a controlled setting with 13 days of 24-hour urine collections. However, the data come from only eight patients with CKD, so generalizability is limited. Our results also cannot be applied to the general population with preserved kidney function. The potential reasons for heterogeneity in 24-hour urine phosphorus among individuals and day-to-day variation within individuals are numerous and may include race, sex, body mass index, caloric intake, diabetes status, and baseline intake of medications such as proton pump inhibitors or diuretics. Thus, investigation into the contributions of such factors would require larger sample sizes of a heterogeneous population of patients with kidney disease, as our small sample does not allow us to parse out the effects of these factors. The lack of a range of controlled phosphorus intakes limits our ability to show relationships with varying intake. Only phosphorus, calcium, and creatinine were measured in the urine samples in the original study, so variability and reliability of additional urine solutes are not available for description or comparison.

These results do not preclude using change in 24-hour urine phosphorus as an outcome related to phosphorus absorption in interventional studies with treatments that have a known mechanism affecting phosphorus absorption; for example, phosphate binders (45) or low-phosphorus diets (46,47). This is because of the experimental study design, where it is appropriate to infer cause and effect resultant of the intervention, particularly when there is a biological mechanism that supports the cause and effect relationship. Instead, our results suggest that caution must be used in interpreting 24-hour urine phosphorus in observational studies or in individual patients in the absence of intervention. Instead of considering 24-hour urine phosphorus as an estimate of phosphorus absorption, our results suggest it should be considered a reflection of whole-body phosphorus retention. However, these conclusions require confirmation from additional studies of more patients CKD, including age-, sex-, and race-matched controls with preserved kidney function.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

K.M.H.G. originated the secondary study aim and design. E.R.S., K.M.H.G., L.D.M., and G.P.M. carried out the secondary data analyses. M.P., C.M.W., G.P.M., and S.M.M. designed the parent study. M.P., K.M.H.G., C.M.W., B.R.M., and S.M.M. conducted the parent study. E.R.S. and K.M.H.G. drafted and revised the manuscript. L.D.M. and E.R.S. made the figures and tables for the manuscript. All authors edited drafts of, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This is a secondary analysis of a randomized, controlled trial registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (identification no.: NCT01161407). The parent study was a randomized, controlled trial funded by Sanofi/Genzyme through an unrestricted investigator-initiated grant to M.P., and in part by a National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Sciences Award (U54-RR025761, Shekhar, Principal Investigator). This secondary analysis was supported through institutional funds of K.M.H.G. and National Institutes of Health K01 grant DK102864 to K.M.H.G.

This study has been presented as an abstract at the American Society for Nutrition Annual Meeting of Experimental Biology, Chicago, IL, April 2017 (Stremke ER, McCabe LD, McCabe GP, Martin BR, Wastney ME, Moe SM, Weaver CM, Peacock M, Hill Gallant KM, FASEB J, 31(1 Supplement): 459.2).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Urinary Phosphorus Excretion: Not What We Have Believed It to Be?,” on pages 973–974.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.00390118/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Uribarri J: Phosphorus homeostasis in normal health and in chronic kidney disease patients with special emphasis on dietary phosphorus intake. Semin Dial 20: 295–301, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karp H, Ekholm P, Kemi V, Itkonen S, Hirvonen T, Närkki S, Lamberg-Allardt C: Differences among total and in vitro digestible phosphorus content of plant foods and beverages. J Ren Nutr 22: 416–422, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang AR, Lazo M, Appel LJ, Gutiérrez OM, Grams ME: High dietary phosphorus intake is associated with all-cause mortality: Results from NHANES III. Am J Clin Nutr 99: 320–327, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calvo MS, Park YK: Changing phosphorus content of the U.S. diet: Potential for adverse effects on bone. J Nutr 126[Suppl]: 1168S–1180S, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isakova T, Wahl P, Vargas GS, Gutiérrez OM, Scialla J, Xie H, Appleby D, Nessel L, Bellovich K, Chen J, Hamm L, Gadegbeku C, Horwitz E, Townsend RR, Anderson CA, Lash JP, Hsu CY, Leonard MB, Wolf M: Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 79: 1370–1378, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine : DRI: Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride, Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf M: Mineral (Mal)adaptation to kidney disease--young investigator award address: American society of nephrology kidney week 2014. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1875–1885, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pool LR, Wolf M: FGF23 and nutritional metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr 37: 247–268, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill Gallant KM: Studying dietary phosphorus intake: The challenge of when a gram is not a gram. Am J Clin Nutr 102: 237–238, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benini O, D’Alessandro C, Gianfaldoni D, Cupisti A: Extra-phosphate load from food additives in commonly eaten foods: A real and insidious danger for renal patients. J Ren Nutr 21: 303–308, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrigan A, Klinger A, Choquette SS, Luzuriaga-McPherson A, Bell EK, Darnell B, Gutierrez OM: Contribution of food additives to sodium and phosphorus content of diets rich in processed foods. J Ren Nutr 24: 13–19, 19e1, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno-Torres R, Ruiz-Lopez MD, Artacho R, Oliva P, Baena F, Baro L, Lopez C: Dietary intake of calcium, magnesium and phosphorus in an elderly population using duplicate diet sampling vs food composition tables. J Nutr Health Aging 5: 253–255, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oenning LL, Vogel J, Calvo MS: Accuracy of methods estimating calcium and phosphorus intake in daily diets. J Am Diet Assoc 88: 1076–1080, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherman RA, Mehta O: Dietary phosphorus restriction in dialysis patients: Potential impact of processed meat, poultry, and fish products as protein sources. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 18–23, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan CM, Leon JB, Sehgal AR: Phosphorus-containing food additives and the accuracy of nutrient databases: Implications for renal patients. J Ren Nutr 17: 350–354, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vorland CJ, Martin BR, Weaver CM, Peacock M, Hill Gallant KMH: Phosphorus balance in adolescent girls and the effect of supplemental dietary calcium. JBMR Plus 2: 103–108, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palomino HL, Rifkin DE, Anderson C, Criqui MH, Whooley MA, Ix JH: 24-hour urine phosphorus excretion and mortality and cardiovascular events. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1202–1210, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson-Cohen C, Ix JH, Smits G, Persky M, Chertow GM, Block GA, Kestenbaum BR: Estimation of 24-hour urine phosphate excretion from spot urine collection: Development of a predictive equation. J Ren Nutr 24: 194–199, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Work Group : KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (113): S1–S130, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isakova T, Ix JH, Sprague SM, Raphael KL, Fried L, Gassman JJ, Raj D, Cheung AK, Kusek JW, Flessner MF, Wolf M, Block GA: Rationale and approaches to phosphate and fibroblast growth factor 23 reduction in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2328–2339, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill KM, Martin BR, Wastney ME, McCabe GP, Moe SM, Weaver CM, Peacock M: Oral calcium carbonate affects calcium but not phosphorus balance in stage 3-4 chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 83: 959–966, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D; Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group : A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med 130: 461–470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weaver CM: Clinical approaches for studying calcium metabolism and its relationship to disease. In: Calcium in Human Health, edited by Weaver CM, Heaney RP, New York, Humana Press, 2006, pp 65–81 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkinson R: Polyethylene glycol 4000 as a continuously administered non-absorbable faecal marker for metabolic balance studies in human subjects. Gut 12: 654–660, 1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schiller LR, Santa Ana CA, Porter J, Fordtran JS: Validation of polyethylene glycol 3350 as a poorly absorbable marker for intestinal perfusion studies. Dig Dis Sci 42: 1–5, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleiss J: The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments, New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemann J: Calcium and phosphate metabolism: An overview in health and in calcium stone formers. In: Kidney Stones: Medical and Surgical Management, edited by Coe F, Favus M, Pak C, Parks J, Preminger G, Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1996, pp 259–288 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho MM, Yi MM: Variability of daily creatinine excretion in healthy adults. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr 40: 469–472, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards OM, Bayliss RI, Millen S: Urinary creatinine excretion as an index of the copleteness of 24-hour urine collections. Lancet 2: 1165–1166, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waterlow JC: Observations on the variability of creatinine excretion. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr 40: 125–129, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenblatt DJ, Ransil BJ, Harmatz JS, Smith TW, Duhme DW, Koch-Weser J: Variability of 24-hour urinary creatinine excretion by normal subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 16: 321–328, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weaver CM, Martin BR, McCabe GP, McCabe LD, Woodward M, Anderson CA, Appel LJ: Individual variation in urinary sodium excretion among adolescent girls on a fixed intake. J Hypertens 34: 1290–1297, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agarwal R: Reproducibility of renal function measurements in adult men with diabetic nephropathy: Research and clinical implications. Am J Nephrol 27: 92–100, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu CY, Propert K, Xie D, Hamm L, He J, Miller E, Ojo A, Shlipak M, Teal V, Townsend R, Weir M, Wilson J, Feldman H; CRIC Investigators : Measured GFR does not outperform estimated GFR in predicting CKD-related complications. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1931–1937, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nafz B, Ehmke H, Wagner CD, Kirchheim HR, Persson PB: Blood pressure variability and urine flow in the conscious dog. Am J Physiol 274: F680–F686, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakuma M, Morimoto Y, Suzuki Y, Suzuki A, Noda S, Nishino K, Ando S, Ishikawa M, Arai H: Availability of 24-h urine collection method on dietary phosphorus intake estimation. J Clin Biochem Nutr 60: 125–129, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rakova N, Kitada K, Lerchl K, Dahlmann A, Birukov A, Daub S, Kopp C, Pedchenko T, Zhang Y, Beck L, Johannes B, Marton A, Müller DN, Rauh M, Luft FC, Titze J: Increased salt consumption induces body water conservation and decreases fluid intake. J Clin Invest 127: 1932–1943, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moe SM, Zidehsarai MP, Chambers MA, Jackman LA, Radcliffe JS, Trevino LL, Donahue SE, Asplin JR: Vegetarian compared with meat dietary protein source and phosphorus homeostasis in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 257–264, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scanni R, vonRotz M, Jehle S, Hulter HN, Krapf R: The human response to acute enteral and parenteral phosphate loads. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2730–2739, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner ME, White CA, Hopman WM, Ward EC, Jeronimo PS, Adams MA, Holden RM: Impaired phosphate tolerance revealed with an acute oral challenge. J Bone Miner Res 33: 113–122, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Selamet U, Tighiouart H, Sarnak MJ, Beck G, Levey AS, Block G, Ix JH: Relationship of dietary phosphate intake with risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease stages 3-5: The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study. Kidney Int 89: 176–184, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spiegel DM, Brady K: Calcium balance in normal individuals and in patients with chronic kidney disease on low- and high-calcium diets. Kidney Int 81: 1116–1122, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill Gallant KM, Spiegel DM: Calcium balance in chronic kidney disease. Curr Osteoporos Rep 15: 214–221, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rothfuss KS, Bode JC, Stange EF, Parlesak A: Urinary excretion of polyethylene glycol 3350 during colonoscopy preparation. Z Gastroenterol 44: 167–172, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Block GA, Wheeler DC, Persky MS, Kestenbaum B, Ketteler M, Spiegel DM, Allison MA, Asplin J, Smits G, Hoofnagle AN, Kooienga L, Thadhani R, Mannstadt M, Wolf M, Chertow GM: Effects of phosphate binders in moderate CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1407–1415, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Isakova T, Gutiérrez OM, Smith K, Epstein M, Keating LK, Jüppner H, Wolf M: Pilot study of dietary phosphorus restriction and phosphorus binders to target fibroblast growth factor 23 in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 584–591, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moorthi RN, Armstrong CL, Janda K, Ponsler-Sipes K, Asplin JR, Moe SM: The effect of a diet containing 70% protein from plants on mineral metabolism and musculoskeletal health in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 40: 582–591, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.