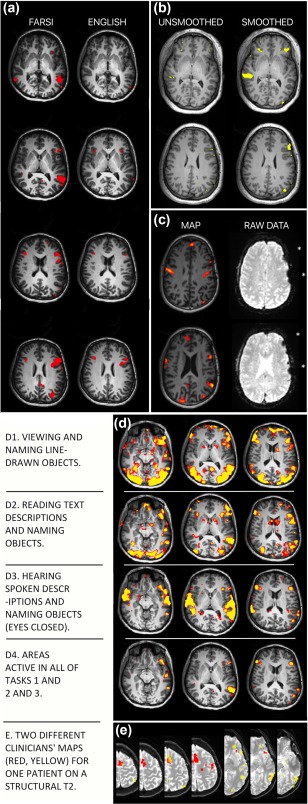

Figure 3.

Language maps will vary in clinically meaningful ways due to multiple variables. Surgical teams can manage these factors by using experts in both imaging (e.g., radiology) and cognition (e.g., neuropsychology) in clinical fMRI design, analysis and interpretation. (a) Language skill. A patient's language ability will change their activation map. Maps using the same tasks in Farsi and English from a patient who reported fluency in, and made medical decisions in English. (b) Data analysis. Each analysis step changes the map. Data “smoothing” removes noise. Whether it is appropriate, and to what degree, is debated. The degree of smoothing in commercial software may be unspecified. Identical analysis without (left) and with (right) smoothing (8 mm kernel). (c) Data quality. A statistical map (left) does not show where raw data are missing (right, asterisks). These areas will not be active even if they are language critical. This map (left) was presented to a surgical team for surgical planning without caveat. (d) Cognitive task. Different language tasks give different maps. Subtle changes in task instructions, patient motivation and cognitive strategy change language maps. (D1) Visual object, (D2) text reading and (D3) auditory tasks are shown as well as (D4) the intersection of these. (e) Analyst expectations. The analyst's perceived goal will change the activation map. Two overlaid maps (red; yellow) generated independently by two clinicians for the same patient (see Benjamin et al., 2017). Analysts were blind to case details. One prioritized frontal (red) and the other temporal (yellow) regions, as when mapping frontal tumor versus temporal lobectomy cases. Overlap in orange.

Source. (e) is reprinted from Benjamin et al., “Presurgical language fMRI.,” (2017); Creative Commons Attribution‐Non‐Commercial License [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]