Abstract

The configurational space sampled by the finger and thumb subdomains of the p66 subunit of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase was investigated by Q-band double electron–electron resonance pulsed electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, a method for determining long-range distances between pairs of nitroxide spin-labels introduced via surface-engineered cysteine residues. Four constructs were examined, each containing two spin-labels in the p66 subunit, one in the finger subdomain and the other in the thumb subdomain. In the unliganded state, open and closed configurations for the finger and thumb subdomains are observed with the distribution between these states modulated by the spin-labels and associated mutations, in contrast to crystallographic data in which the unliganded state crystallizes in the closed conformation. Upon addition of double-stranded DNA, all constructs adopt open conformations consistent with previous crystallographic data in which the position of the thumb and finger subdomains is determined by contacts with the bound oligonucleotide duplex (DNA or DNA/RNA). Likewise, binary complexes with five different non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors are in open or partially open conformations, indicating that binding of the inhibitor to the palm subdomain indirectly restricts the conformational space sampled by the finger and thumb subdomains.

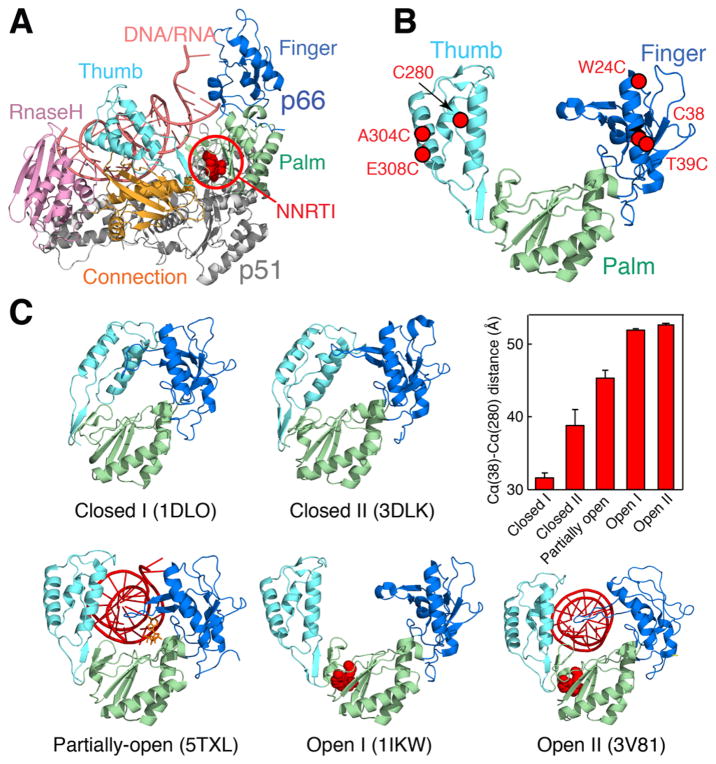

Human immunodeficiency virus type I reverse transcriptase (HIV-1 RT) catalyzes the conversion of single-stranded virally encoded RNA into double-stranded proviral DNA, the first step in a complex process that eventually leads to integration of viral DNA into the host genome.1 Mature HIV-1 RT is a heterodimer comprising p66 and p51 subunits that differ in the presence and absence, respectively, of the RNase H domain. DNA polymerase and RNase H activities, as well as the binding site for non-nucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTI), reside in the p66 subunit, while the p51 subunit serves as a structural scaffold (Figure 1A).2–5 The polymerase domain comprises finger, palm, and thumb subdomains (Figure 1B) and is attached to the RNase H domain via a connection domain.6,7 Crystal structures of HIV-RT in various states reveal that the polymerase domain of p66 can adopt closed (ligand-free), partially open (ternary complexes with DNA and nucleotide triphosphates), and open (binary complexes with NNRTIs and ternary complexes with DNA or DNA/RNA and NNRTIs) conformations, differing in the spatial relationship of the finger and thumb subdomains relative to one another (Figure 1C). Here we explore the disposition of the finger and thumb subdomains of p66 within the mature HIV-1 RT p66/p51 heterodimer in a variety of unliganded and liganded states by Q-band pulsed double electron–electron resonance (DEER) electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, a technique that affords long-range distance measurements between pairs of nitroxide spin-labels attached to appropriately engineered surface cysteines.9

Figure 1.

HIV-1 RT. (A) Crystal structure of a ternary complex of HIV-1 RT p66/p51 with a DNA/RNA hybrid and the NNTRI efavirenz (Protein Data Bank entry 4B3O).8 The domains and subdomains of p66 are labeled and color-coded; p51 is colored gray. (B) Finger, palm, and thumb subdomains of p66 from the structure shown in panel A with the sites of nitroxide spin-labeling indicated. (C) Classes of conformational states of the finger (blue) and thumb (cyan) subdomains displayed using the same orientation of the palm domain (green), together with a bar graph of the corresponding Cα–Cα distances between C38 and C280 derived from the crystal structures (error bars show one standard deviation).

We used four p66 constructs, each containing two nitroxide spin-labels (R1), one in the finger subdomain and the other in the thumb subdomain (Figure 1B): C38-R1/C280-R1, C38-R1/A304C-R1, W24C-R1/C280-R1, and T39C-R1/E308C-R1. They were generated by conjugation of (1-acetoxy-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-δ-3-pyrroline-3-methyl)methanethiosulfonate (MTSL) to the surface-exposed cysteines via a disulfide linkage.10 C38 and C280 are naturally occurring cysteine residues in HIV-1 RT and were mutated to alanine, as appropriate, in constructs in which R1 was not attached to one or both of these residues. Previous work has shown that both cysteines can be replaced with alanine without any significant impact on nucleic acid binding or polymerase activity.11 Complete protein deuteration was employed to increase the spin-label phase memory relaxation time in the DEER experiments, thereby increasing the signal-to-noise ratio and extending the accessible distance range.12–15 Full experimental details of expression, purification, deuterium incorporation and spin-labeling, DNA/RNA binding, and polymerase activity assays are given in the Experimental section of the Supporting Information. Using a fluorescence polarization assay, three of the four spin-labeled constructs bind 5′-fluorescein-labeled DNA/RNA with equilibrium dissociation constants (KD ~ 2.2–4.2 nM) comparable to that of wild type HIV-1 RT (KD ~ 3.5 nM), while the fourth, W24C-R1/C280-R1, binds an order of magnitude tighter (KD ~ 0.2 nM) (Figure S1A), possibly because of enhanced hydrophobic interactions between the W24C-R1 spin-label and DNA relative to W24 (see Figures S2 and S3). In addition, all four spin-labeled constructs retain polymerase activity measured via elongation of a DNA/RNA hybrid by addition of a single nucleotide (Figure S1B).

The p66/p66 homodimer is weak compared to the p66/p51 heterodimer.16,17 Under the conditions used for DEER (Figure 2), p66 alone exists as an approximately equal mixture of monomer and homodimer,18 giving rise to three distances between pairs of nitroxide spin-labels [one intramolecular and two intermolecular (Figure 2A, left)], as observed for the DEER-derived P(r) distance distribution for the C38-R1/C280-R1 construct (Figure 2B, blue trace). In the absence of conformational heterogeneity, the p66/p51 heterodimer should exhibit only a single intrasubunit distance between a pair of spin-labels (Figure 2A, right). This is reflected in the DEER-derived P(r) distribution obtained upon addition of excess deuterated p51 to ensure that all nitroxide-labeled p66 resides in the p66/p51 heterodimer (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Generating mature p66/p51 HIV-1 RT with all nitroxide-labeled p66 in the heterodimer. (A) Schematic showing that p66 alone (blue subunit) exists as a monomer/homodimer mixture with three potential distances (one intramolecular and two intermolecular) between a pair of spin-labels (indicated by the green circles). A p66/p51 heterodimer in which all spin-labeled p66 resides in the heterodimer is obtained by the addition of excess p51 (red subunit). (B) DEER-derived P(r) distance distributions (represented as a sum of Gaussians using the program DD20) for 50 μM C38-R1/C280-R1 p66 alone (blue) and in the presence of 350 μM p51 (red). The corresponding raw Q-band DEER echo curves recorded at 50 K are shown as insets. Experimental conditions: 50 mM Tris (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 30%/70% (w/v) d8-glycerol/D2O.

Predicted distance distributions19 among the four pairs of spin-labels calculated from crystal structures (see Figures S2 and S3) are listed in Table 1. The crystal structures can be grouped into five classes (Figure 1C): closed I and closed II corresponding to unliganded HIV-1 RT, partially open comprising ternary complexes with DNA and various incoming nucleotides, and open I and open II corresponding to binary complexes with a NNRTI and ternary complexes with DNA or DNA/RNA and a NNRTI, respectively.

Table 1.

Predicted Distances between Pairs of Spin-Labels in the p66 Subunit of HIV-1 RT Calculated from Crystal Structuresa

| construct | mean distance ± width at half-height (Å)b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| closed | partially openc | open | |||

|

|

|

||||

| I | II | I | IIc | ||

| C38/C280 | 39 ± 4 | 48 ± 3 | 50 ± 7 (47 ± 5) | 59 ± 4 | 54 ± 5 (49 ± 5) |

| C38/A304C | 50 ± 3 | 55 ± 3 | 58 ± 4 (58 ± 4) | 67 ± 3 | 65 ± 5 (61 ± 5) |

| W24C/C280 | 27 ± 5 | 32 ± 5 | 37 ± 5 (34 ± 4) | 44 ± 5 | 43 ± 4 (38 ± 4) |

| T39C/E308C | 54 ± 4 | 58 ± 4 | 62 ± 5 (61 ± 4) | 67 ± 3 | 65 ± 4 (61 ± 5) |

The Protein Data Bank codes are as follows: closed I, 1DLO, 1HQE, 2IAJ, 1MU2, 4ZHR, and 1QE1; closed II, 3DLK, 3IG1, and 4DG1; partially open, 5TXL, 5TXM, 3V4I, 3KJV, and 3KK3; open I, 3QIP, 1IKW, 4G1Q, 1KLM, 1SV5, and 1JLE; open II, 4B3O and 3V81. References for the individual structures are listed in Table S1.

The mean distances between spin-labels and the widths at half-height of the P(r) distributions are calculated from the crystal structures using MMM2013.2.19

The numbers shown in parentheses are the values calculated with the nucleic acid coordinates removed.

Background-corrected Q-band DEER echo curves for two of the HIV-1 RT spin-labeled constructs (C38-R1/C280-R1 and W24C-R1/C280-R1), obtained in the presence (blue) and absence (red) of a 24 bp DNA duplex with a three-nucleotide overhang at one of the 3′-ends, are shown in Figure 3A. Full details of DEER data acquisition and analysis are given in the Experimental section of the Supporting Information, and the raw and background-corrected echo curves for all DEER data are provided in Figures S4–S10. The P(r) distributions obtained from a two-Gaussian fit to the DEER data are shown in Figure 3B and compared to the predicted distributions from crystal structures in the open and closed states. The mean distances and widths of the P(r) distributions are summarized in Table 2 (and Tables S2–S5).

Figure 3.

Experimental DEER data and P(r) distributions for p66 spin-labeled HIV-RT in the absence and presence of double-stranded DNA. (A) Examples of background-corrected DEER echo curves (recorded at 50 K) colored red (unliganded) and blue (with DNA) with the best-fit curves obtained by DD20 analysis colored black. (B) DEER-derived P(r) distributions, obtained by a two-Gaussian fit using DD,20 shown by the red (unliganded) and blue (with DNA) lines compared to predicted P(r) distributions (filled-in Gaussians, color-coded as indicated in the bottom left panel) obtained from an ensemble of closed I, closed II, open I, and open II (calculated including nucleic acid coordinates) crystal structures using MMMv2013.2.19 For W24C-R1/C280-R1, the predicted P(r) distributions for open I and II states are superimposed. The concentrations of the p66 spin-labeled HIV-RT heterodimer and DNA duplex are 50 μM and 0.5 mM, respectively.

Table 2.

Experimental Means and Widths of Distance Distributions between Pairs of Spin-Labels in HIV-RT from DEERa

| construct | mean distance ± width at half-height (Å) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| unliganded | with DNA | with NNRTIs | |

| C38/C280 | 56 ± 3b | 56 ± 4 | 46 ± 6 |

| C38/A304C | 83 ± 9 (56%)c | 83 ± 8 | 56 ± 6 |

| 42 ± 8 (44%)c | |||

| W24C/C280 | 22 ± 5 (56%)c | 46 ± 5 | 45 ± 4 |

| 42 ± 14 (44%)c | |||

| T39C/E308C | 53 ± 3b | 68 ± 3 | 67 ± 3 |

Obtained from a two-Gaussian fit using the program DD.20 No significant differences are found using three-Gaussian fits or validated Tikhonov regularization22 (see Tables S2–S5).

The P(r) distributions for the C38-R1/C280-R1 and T39C-R1/E308C-R1 constructs contain an additional broad component with widths of 13 and 20 Å, respectively, and corresponding mean distances of 56 and 58 Å, respectively, very close to the mean distance of the narrow component (see the Experimental section of the Supporting Information).

Values in parentheses refer to conformer populations.

All four HIV-1 RT–DNA complexes are in an open conformation (Figure 3B), as expected because the DNA binding site is not accessible in the closed state (see Figure 1C). The C38-R1/C280-R1 construct predominantly samples the open I state; for the W24C-R1/C280-R1 and T39C-R1/E308C-R1 constructs, no distinction can be made between open I and open II conformations as the predicted distance distributions overlap, and for the C38-R1/A304C-R1 construct, the distance between the spin-labels is significantly longer (~83 Å) than in any of the open conformation crystal structures [65–67 Å (Table 1)].

The situation for unliganded HIV-1 RT is more complex with the populations of open and closed states impacted by the positions of the nitroxide spin-labels (Figure 3B and Table 2). C38-R1/C280-R1 and T39-R1/E308C-R1 adopt exclusively open and closed conformations, respectively. C38-R1/A304C-R1 and W24C-R1/C280C-R1, however, exist as a mixture of open and closed states. C38-R1/A304C-R1 is predominantly open (~80% with the same distance distribution as the complex with DNA), and the widths of the distance distributions for the open and closed states are comparable. The occupancies of the closed and open states for W24C-R1/C280-R1 are more comparable (56 and 44%, respectively), but the width of the P(r) distribution for the open state is larger by a factor of 3 (Table 2). The results are consistent with those obtained for a W24C-R1/K287C-R1 construct by line shape analysis of continuous wave X-band EPR spectra, where an open conformation is found in the frozen state at 170 K and a temperature-dependent mixture of open and closed states is observed in solution21 (note that the W24C-R1/K287C-R1 construct is not suitable for DEER analysis as the distance between spin-labels is <15 Å in the closed state). These results suggest that, in all likelihood, crystal packing forces may play a significant role in pushing the equilibrium to the closed conformation in crystal structures of unliganded RT.

We also investigated the impact of five different NNRTIs [etravirine, rilpivirine, delavirdine, efavirenz, and nevirapine (see Figure S11)] on the disposition of the finger and thumb subdomains. The results are summarized in Figure 4, Table 2, and Tables S2–S5. Each doubly spin-labeled construct exhibits the same conformation for all NNRTIs. Upon addition of NNTRIs, the distances between spin-labels are decreased for the C38-R1/C280-R1 and C38-R1/A304C-R1 constructs where the predominant species in the unliganded state is in the open conformation, while the converse is true for the W24C-R1/C280-R1 and T39C-R1/E308C-R1 constructs where the closed conformation constitutes the major species in the unliganded state. The complexes with the C38-R1/C280-R1 construct are predominantly in the open II conformation; those with the W24C-R1/C280-R1 and T39C/E308C-R1 constructs are in the open I conformation, and the C38-R1/A304C-R1 construct is in the partially open conformation. In contrast, crystal structures of binary complexes of HIV-RT with these five NNRTIs are all in the open I state.3,4 Thus, we deduce that the dispositions of the finger and thumb subdomains of p66, while largely open or partially open, are influenced to a minor degree by spin-labeling.

Figure 4.

Experimental DEER data and P(r) distributions for p66 spin-labeled HIV-RT in the presence of five different NNRTIs. (A) Examples of background-corrected DEER echo curves (recorded at 50 K) with the best-fit curves from DD20 analysis shown as black lines. (B) DEER-derived P(r) distributions obtained by a two-Gaussian fit using DD20 (lines color-coded according to NNRTI as shown in the top left panel) compared to predicted P(r) distributions (filled-in Gaussians color-coded as indicated in the bottom left panel) for the different structural classes observed in crystal structures. The predicted P(r) distributions for the open I and open II states are shown in all four panels; the closed I, closed II, and partially open states are also shown for C38-R1/A304C-R1. Nucleic acid coordinates were omitted from the calculations. The distance around 80 Å in the case of the complex of the C38-R1/A304C-R1 construct with delavirdine arises from residual free RT. The concentrations of the p66 spin-labeled HIV-RT heterodimer and inhibitor are 50 μM and 1 mM, respectively.

In conclusion, the configurational space sampled by the finger and thumb subdomains in the p66 subunit of the mature HIV-RT p66/p51 heterodimer is quite variable, a finding that is consistent with the paucity of interactions between the finger, thumb, and palm subdomains observed in crystal structures (Figure 1). In the unliganded state, the distribution between closed and open conformations is clearly influenced by the introduction of the spin-labels and accompanying mutations (Figure 3). Because neither the nitroxide spin-labels nor the additional mutations substituting the naturally occurring cysteines at positions 38 and 280 with alanine where appropriate are located in sites that would appear to either hinder or favor one conformation over another (e.g., by steric hindrance), these results suggest that the difference in energy between the open and closed conformations in wild type HIV-RT is rather small and can easily be tipped toward either the open or closed states by relatively minor perturbations (e.g., spin-labeling or temperature21). In addition, the population of open and closed states in unliganded HIV-RT appears to have little impact on either DNA/RNA binding affinity or DNA polymerase activity (Figure S1). The binding site for oligonucleotide duplexes is accessible only in open type conformations. Consistent with this observation is the fact that all the complexes with double-stranded DNA are in the open state (Figure 3). However, while the distances between spin-labels for three of the complexes (C38-R1/C280-R1, W24C-R1/C280-R1, and T39C-R1/E308C-R1) are consistent with the open II conformation found in crystal structures of ternary complexes with DNA or DNA/RNA and an NNRTI, the distance between C38-R1 and A304C-R1 is close to 20 Å longer than that predicted from the crystal structures. Finally, binary complexes with NNRTIs are all found in open or partially open conformations with little variation in mean distances between a given set of spin-labels in the different complexes (Figure 4), indicating that the intermolecular interactions between the NNRTI and the palm subdomain (Figure 1) serve to indirectly restrict the conformational space sampled by the finger and thumb subdomains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and by the AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health (to G.M.C.).

The authors thank Drs. Mengli Cai and James Baber for discussions.

ABBREVIATIONS

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus type I

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- DEER

double electron–electron resonance

Footnotes

Author Contributions

T.S. and G.M.C. designed the research. T.S. performed the research. L.T. performed RNA/DNA binding and polymerase assays. T.S. and G.M.C. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.bio-chem.7b01035.

Full details of experimental procedures and analysis, together with five supplementary tables and 13 supplementary figures (PDF)

References

- 1.Herschhorn A, Hizi A. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:2717–2747. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.di Marzo Veronese F, Copeland TD, DeVico AL, Rahman R, Oroszlan S, Gallo RC, Sarngadharan MG. Science. 1986;231:1289–1291. doi: 10.1126/science.2418504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarafianos SG, Marchand B, Das K, Himmel DM, Parniak MA, Hughes SH, Arnold E. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:693–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das K, Arnold E. Curr Opin Virol. 2013;3:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das K, Arnold E. Curr Opin Virol. 2013;3:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohlstaedt LA, Wang J, Friedman JM, Rice PA, Steitz TA. Science. 1992;256:1783–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.1377403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobo-Molina A, Ding J, Nanni RG, Clark AD, Jr, Lu X, Tantillo C, Williams RL, Kamer G, Ferris AL, Clark P, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6320–6324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapkouski M, Tian L, Miller JT, Le Grice SFJ, Yang W. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:230–236. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeschke G. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2012;63:419–446. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032511-143716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hubbell WL, Cafiso DS, Altenbach C. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:735–739. doi: 10.1038/78956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer M, Lifshitz R, Katz T, Liefer I, Ben-Artzi H, Gorecki M, Panet A, Zeelon E. Protein Expression Purif. 1992;3:301–307. doi: 10.1016/1046-5928(92)90005-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward R, Bowman A, Sozudogru E, El-Mkami H, Owen-Hughes T, Norman DG. J Magn Reson. 2010;207:164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baber JL, Louis JM, Clore GM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2015;54:5336–5339. doi: 10.1002/anie.201500640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Mkami H, Norman DG. Methods Enzymol. 2015;564:125–152. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2015.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt T, Walti MA, Baber JL, Hustedt EJ, Clore GM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:15905–15909. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Divita G, Rittinger K, Restle T, Immendorfer U, Goody RS. Biochemistry. 1995;34:16337–16346. doi: 10.1021/bi00050a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharaf NG, Poliner E, Slack RL, Christen MT, Byeon IJ, Parniak MA, Gronenborn AM, Ishima R. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Genet. 2014;82:2343–2352. doi: 10.1002/prot.24594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt T, Ghirlando R, Baber J, Clore GM. ChemPhysChem. 2016;17:2987–2991. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201600726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polyhach Y, Bordignon E, Jeschke G. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:2356–2366. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01865a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandon S, Beth AH, Hustedt EJ. J Magn Reson. 2012;218:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kensch O, Restle T, Wohrl BM, Goody RS, Steinhoff HJ. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:1029–1039. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeschke G, Chechik V, Ionita P, Godt A, Zimmermann H, Banham J, Timmel CR, Hilger D, Jung H. Appl Magn Reson. 2006;30:473–498. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.