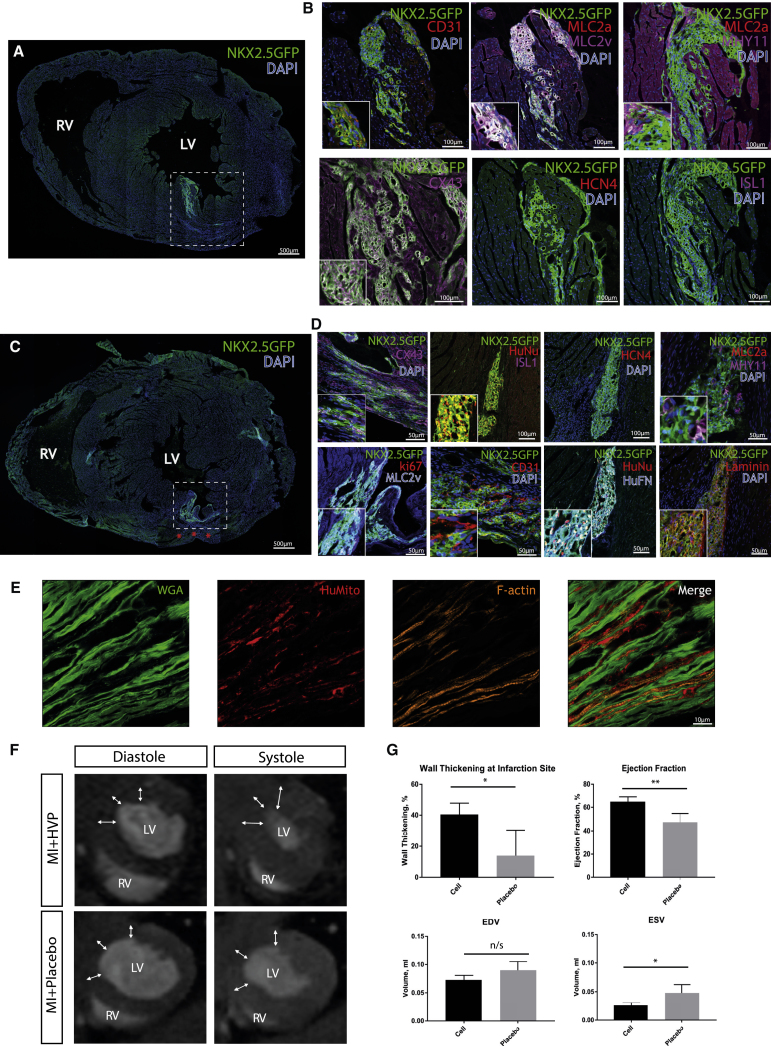

Figure 4.

In Vivo Transplantation of HVPs into Healthy and Injured Hearts

(A) White dashed box denotes the location of the HVP graft 8 months following intramyocardial injection into a healthy heart. (B) Immunofluorescence staining showed that HVP ventricular grafts in the heart expressed NKX2.5-GFP (green), MLC2v, connexin 43, and MHY11; a minority of cells co-expressed MLC2a and was negative for HCN4 and ISL1. CD31 was only present outside the graft. (C) The white dashed box identifies the localization and the engraftment of the xeno tissue 2 months after injection of the HVPs into the border zone of MI hearts. Red asterisks denote infarction site. (D) Immunofluorescence staining showed that HVP ventricular grafts in post-MI hearts co-expressed NKX2.5-GFP (green), connexin 43, human nuclei, MLC2v, MHY11, human fibronectin, and laminin. A minority of cells was positive for ki67; MLC2a, ISL1, and HCN4 staining was not observed. Endothelial marker CD31 was detected in close proximity to the HVP graft. (E) High-resolution imaging of the border zone of post-MI HVP grafts demonstrated engrafted, differentiated cardiomyocytes of human origin, with well-organized sarcomeres (stains of cell membrane [WGA, green], human mitochondria [red], and F-actin [orange]). (F) MRI assessment of post-MI hearts 2 months following HVP transplantation showed improved global and local function in comparison with placebo. Representative short axis images show wall thickness at the site of induced infarction (arrows). LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle. (G) Mean measurements ± SD of wall thickening, ejection fraction, and volume during end diastole (EDV) and end systole (ESV). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; n/s, not significant.