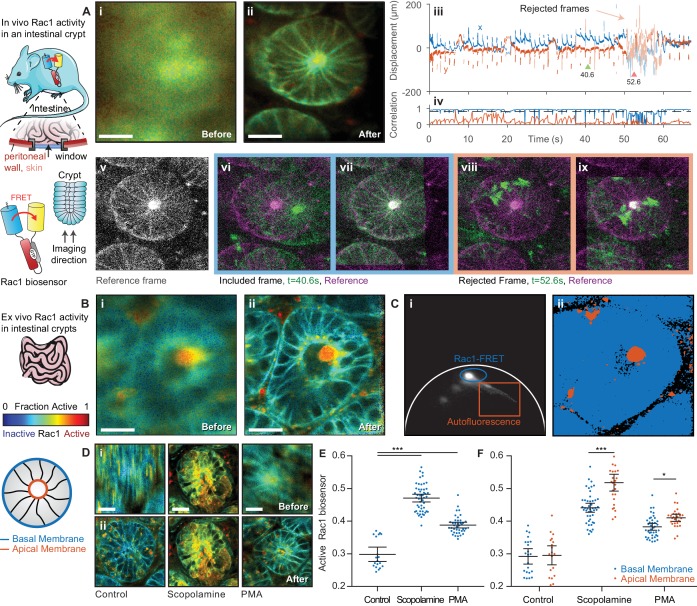

Figure 4. FLIM of intestinal crypts from the Rac1-FRET biosensor mouse in vivo and ex vivo using motion compensation.

(A) Imaging of intestinal crypts in vivo using an abdominal titanium imaging window (i–ii) Example FRET biosensor activity maps (i) before and (ii) after motion compensation showing fraction of active FRET biosensor determined by fitting to a FRET model accounting for the complex exponential decay of ECFP. White scale bars, 50 μm. (iii) Estimated displacement traces in (blue) x and (red) y directions over time. Pastel shaded regions indicate frames that could not be successfully corrected with correlation coefficients < 0.8. (iv) Correlation between reference frame and (red) uncorrected and (blue) corrected images over time. Black dashed line denotes threshold (0.8) used to reject frames which could not be corrected. (v) Selected reference frame (vi,vii) Example of a successfully corrected frame (vi) before and (vii) after correction. (viii,ix) Example of a frame that could not be corrected. (B) Imaging of intestinal crypts ex vivo. (i–iv) as (A), no correlation threshold applied. (C) (i) Phasor plot of image shown in (B) to separate biosensor fluorescence (blue) from autofluorescence (red) and i) back projection of selected gates. (D) Intensity merged lifetime images of crypts (i) before and (ii) after motion compensation treated with (left-right) no drug, 200 nM PMA or 1 μM scopolamine. White scale bars 50 μm. (E) Quantification of fraction of active biosensor in crypts after drug treatment. (F) Subcellular analysis of fraction of active biosensor in basal (blue) and apical (red) membranes after drug treatment, shown per cell. Error bars show means ± SEM. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 using one-way ANOVA. Mouse and intestine illustrations were adapted from Servier Medial Art, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.