Abstract

Apert syndrome is a rare congenital disorder characterised by craniosynostosis, midface hypoplasia and syndactyly of hands and feet. Here we present a case of a 44-year-old woman, with a genetic diagnosis of Apert syndrome from birth, who presented with symptomatic left-sided hip osteoarthritis secondary to femoral abnormalities. She proceeded to have a total hip replacement. This case report describes the rare occurrence to identify a possible association between Apert syndrome and hip abnormalities.

Keywords: congenital disorders, paediatric surgery, orthopaedic and trauma surgery, developmental paediatrocs

Background

Apert syndrome (AS) is a rare congenital disorder first described by French paediatrician, Eugene Apert.1 It has been named Apert syndrome rather than Apert’s syndrome, as Apert neither had nor owned the syndrome that bears his name.2 It is a form of acrocephalodactyly characterised by craniosynostosis, midface hypoplasia and symmetrical syndactyly of hands and feet.3 Cardiorespiratory, neurological, genitourinary and vertebral features are rarely associated and reported with AS.4 The syndrome is estimated to be prevalent in one in 65 000 newborn babies.5

Dysplasia is defined as abnormal growth or development. Hip dysplasia is the most common hip abnormality seen in the population.6 It is a dynamic and mechanical disorder characterised by a shallow acetabulum, which results in instability of the hip joint. The most common aetiology is termed developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), as the age of onset can vary.7 The incidence has been reported between 3% and 5%.6 8 DDH is now the leading cause of early onset osteoarthritis before the age of 60 years.9 10 Common radiographic findings of DDH include a shallow acetabulum, hip subluxation or delay in ossification of the superior femoral epiphysis.7

This case is important because it raises the rare possibility of an association of AS that has not been reported before. If hip abnormalities, such as hip dysplasia (HD), are screened earlier, this can be managed sooner and not result in early hip arthroplasty.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old nursery teacher presented to the elective orthopaedic outpatient clinic with left hip and groin pain over a 12-month period. She struggled with foot care and when getting down on the floor to help infants when at work.

She was genetically diagnosed with AS from an early age, postnatal. She has had over 13 previous surgeries to address craniofacial abnormalities. She is otherwise fit and well.

There was no family history of HD or any other inflammatory or autoimmune disorders. She has had problems with her development, in particular gait. However, this was deemed to be due to developmental delay rather than any organic pathology. No formal ultrasound was performed on the hips to diagnose HD. However, a later collateral history from the mother revealed that she did have a persistent problem with her hips, particularly pain and discomfort. This limited her to the extent that she could not take part in physical education at school. She did see an orthopaedic specialist and a X-ray was performed at age seven but apparently did, ‘not show any problems worth intervening’, as quoted from the mother.

She is married and lives a normal life with her 8-year-old son.

Examination revealed an antalgic gait, an exaggerated lumbar lordosis, with almost no internal rotation of the left hip and reproduction of her pain with hip movements.

Investigations

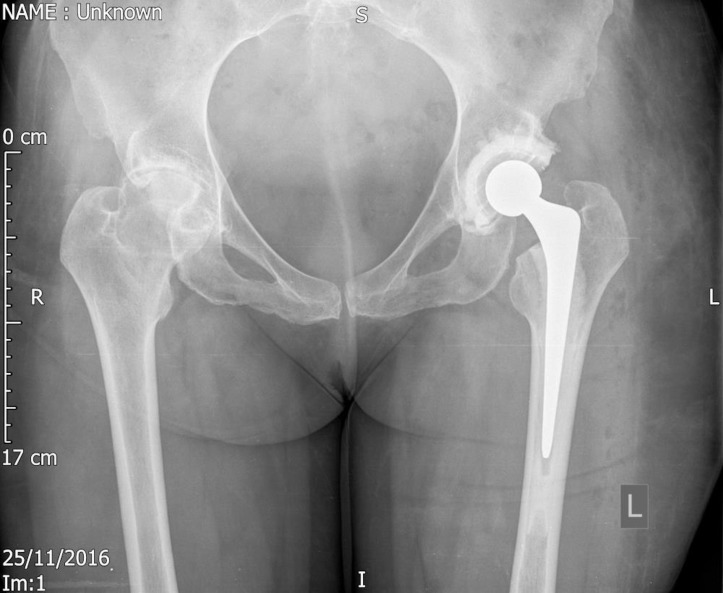

Initial radiographs of the pelvis and hip (figure 1) demonstrated arthritis of both hips with coxa brevia, short femoral neck and a shallower acetabulum, abnormal features that can be described as dysplasia. Repeat radiographs 6 months later showed worsening arthritis, worse on the left side. The radiographic features of dysplasia in this patient were not typical for HD, and particularly DDH.

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis demonstrating coxa brevia, short femoral neck, atypical signs of hip dysplasia and bilateral moderate osteoarthritis of the hip joints.

Unfortunately, no childhood imaging was available.

Differential diagnosis

Hip dysplasia.

Avascular necrosis.

Multiple epiphysial dysplasia.

Treatment

We initially managed this young woman non-operatively to address her pain with different analgesia techniques, physiotherapy input, lifestyle changes and lastly hip joint injections.

After a 6-months period, her pain had not improved and, in fact, worsened despite all the non-operative interventions. She eventually underwent total hip arthroplasty—cemented OGEE (DePuy) acetabular cup with a cemented Exeter (Stryker) femoral stem (figures 2 and 3). The operation itself was not any more challenging than performing a total hip replacement on a young patient. As predicted from preoperative planning, a smaller stem was used with a narrower offset to accommodate her contralateral anatomy. Leg length was slightly more difficult to perfect, however, this was correctable by fixing the stem in a more sunken position and increasing the offset on the head, without compromising stability.

Figure 2.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis showing the new total hip replacement in situ.

Figure 3.

Lateral radiograph of the left hip showing the new total hip replacement in situ.

Outcome and follow-up

The postoperative recovery was routine and uneventful with hospital discharge occurring at 3 days. She had mobilised well with physiotherapists with the help of crutches.

At 6 weeks follow-up, she was mobilising independently and pain free. Her 6 weekly postoperative radiographs demonstrated excellent prosthesis positioning. Twelve-month follow-up demonstrated excellent outcome with an Oxford hip score of 47/48 and no radiographic change to her hip joint prosthesis.

Discussion

AS is one of the eight disorders part of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)-related craniosynostosis spectrum.11 Patients with AS are predominantly characterised by cranio-facial abnormalities.2 Very little literature exists regarding extracraniofacial features. AS has been associated with some skeletal abnormalities such as spinal scoliosis, cervical spine fusion, symmetric syndactyly of hands and feet.4 12–14 Even less literature has been published regarding the association between AS and hip abnormalities. We hypothesise that this may be due to lack of patients due to rarity of the disease as well as lack of reporting.

Cohen et al demonstrated a wide range of skeletal abnormalities including the shoulders, humeri, elbows, hips, knees, rib cage and spine, although in a small number of patients. As confirmed in the literature, little attention has been given to the hip joint in AS as most case reports do not report them due to absent clinical abnormality. Nine patients with AS were found to have hip abnormalities; these included acetabular, femoral head and neck alterations. Radiographic appearances of these nine cases were consistent with our findings such as a short broad femoral neck, prominent greater trochanters and unilateral acetabular dysplasia. Other findings included frequent asymmetry and irregularity of femoral head and greater trochanter ossification centres, wide interpubic distances and complete hip dislocation. However, no denominator could be given due to the lack of pelvic radiographs.14

The radiographic features can be also seen in the other FGFR-related syndromes: Crouzon syndrome, Pfeiffer syndrome or Muenke syndrome.11 However, other aetiologies such as avascular necrosis and multiple epiphysial dysplasia, should be included in the differential.

Hip arthritis before the age of 60 has been strongly linked with HD. Jacobsen showed that HD was a significant risk factor for hip osteoarthritis development, particularly in women.10 15 The primary area of degeneration in dysplastic hips was in the anterolateral quadrant of the joint.15

Joint replacement should be the last resort in young patients.9 Not only is it a more technically demanding procedure due to the distorted anatomy,16 but it is also associated with a higher rate of revision surgery and dislocation rate.15 17 The major timeline concern with dislocations in patients with HD is within the first 6 months postoperative.16 Studies have advocated the use of both cemented and cementless prosthesis with good long-term survival results.18

In conclusion, there is not enough evidence to suggest that, patients with AS are susceptible to hip dysplasia but can present with features of dysplasia and hip abnormalities in the hip joint. One of the weaknesses in our case is the lack of pelvic radiograph documentation, which was a common finding in the literature. We, therefore, suggest further radiographic documentation of the hip joint in patients with AS to support our theory. Another weakness is the lack of cases. We present this case in the hope that other clinicians treating patients with AS will be screened for hip abnormalities and report their cases. This could potentially aid to an earlier diagnosis to facilitate preventative management and avoid early arthroplasty surgery. This would also aid further research to confirm whether our findings are simply a coincidence or whether an association can be made.

Learning points.

Patients with Apert syndrome could have associated hip abnormalities.

Early radiographic documentation of the hip joint can help with diagnosis and research.

Hip dysplasia is responsible as the leading cause of early onset hip arthritis.

Total hip arthroplasty should be the last resort in young patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have contributed in the writing of this article.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.DeGiovanni CV, Jong C, Woollons A. What syndrome is this? Apert syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol 2007;24:186–8. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00372.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MM. Apert syndrome, not Apert’s syndrome: apert neither had nor owned the syndrome that bears his name. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;100:532–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatia PV, Patel PS, Jani YV, et al. Apert’s syndrome: report of a rare case. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2013;17:294–7. 10.4103/0973-029X.119782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar GR, Jyothsna M, Ahmed SB, et al. Apert’s syndrome. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2014;7:69–72. 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Athanasiadis AP, Zafrakas M, Polychronou P, et al. Apert syndrome: the current role of prenatal ultrasound and genetic analysis in diagnosis and counselling. Fetal Diagn Ther 2008;24:495–8. 10.1159/000181186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S. Hip dysplasia: a significant risk factor for the development of hip osteoarthritis. A cross-sectional survey. Rheumatology 2005;44:211–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aronsson DD, Goldberg MJ, Kling TF, et al. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatrics 1994;94:201–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Søballe K, et al. Hip dysplasia and osteoarthrosis: a survey of 4151 subjects from the Osteoarthrosis Substudy of the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Acta Orthop 2005;76:149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronson J. Osteoarthritis of the young adult hip: etiology and treatment. Instr Course Lect 1986;35:119–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stulberg SD. Unrecognized childhood hip disease: a major cause of idiopathic osteoarthritis of the hip. Louis (M): CV Mosby: In: Proceedings of the Third Open Scientific Meeting of the Hip Society. St, 1975:212–28. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robin NH, Marni J, Haldeman-Englert CR. FGFR-related craniosynostosis syndromes. Gene Reviews (Internet). Seattle: University of Washington, 1993-2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreiborg S, Barr M, Cohen MM. Cervical spine in the Apert syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1992;43:704–8. 10.1002/ajmg.1320430411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen MM, Kreiborg S. Hands and feet in the Apert syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1995;57:82–96. 10.1002/ajmg.1320570119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen MM, Kreiborg S. Skeletal abnormalities in the Apert syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1993;47:624–32. 10.1002/ajmg.1320470509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen S. Adult hip dysplasia and osteoarthritis. Studies in radiology and clinical epidemiology. Acta Orthop Suppl 2006;77:1–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang S, Cui Q. Total hip arthroplasty in developmental dysplasia of the hip: review of anatomy, techniques and outcomes. World J Orthop 2012;3:42–8. 10.5312/wjo.v3.i5.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thillemann TM, Pedersen AB, Johnsen SP, et al. Implant survival after primary total hip arthroplasty due to childhood hip disorders Results from the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Registry. Acta Orthop 2008;79:769–76. 10.1080/17453670810016830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faldini C, Miscione MT, Chehrassan M, et al. Congenital hip dysplasia treated by total hip arthroplasty using cementless tapered stem in patients younger than 50 years old: results after 12-years follow-up. Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology 2011;12:213–8. 10.1007/s10195-011-0170-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]