Abstract

Free fatty acid receptor 2 (FFAR2, also named GPR43), is activated by short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, that are produced when gut bacteria ferment dietary fiber. FFAR2 has been suggested to regulate colonic inflammation, which is a major risk factor for the development of colon cancer and is also linked to epigenetic dysregulation in colon carcinogenesis. The current study assessed whether FFAR2, acting as an epigenetic regulator, protects against colon carcinogenesis. To mimic the mild inflammation that promotes human colon cancer, we treated mice with dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) overnight, which avoids excessive inflammation but induces mild inflammation that promotes colon carcinogenesis in the ApcMin/+ and the azoxymethane (AOM)-treated mice. Our results showed that FFAR2 deficiency promotes the development of colon adenoma in the ApcMin/+/DSS mice and the progression of adenoma to adenocarcinoma in the AOM/DSS mice. FFAR2’s downstream cAMP–PKA–CREB pathway was enhanced, leading to overexpression of histone deacetylases (HDACs) in the FFAR2-deficient mice. ChIP-qPCR analysis revealed differential binding of H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 histone marks onto the promoter regions of inflammation suppressors (e.g., sfrp1, dkk3, socs1), resulting in decreased expression of these genes in the FFAR2-deficient mice. Also, more neutrophils infiltrated into tumors and colon lamina propria of the FFAR2-deficient mice. Depletion of neutrophils blocked the progression of colon tumors. In addition, FFAR2 is required for butyrate to suppress HDAC expression and hypermethylation of inflammation suppressors. Therefore, our results suggest that FFAR2 is an epigenetic tumor suppressor that acts at multiple stages of colon carcinogenesis.

Keywords: FFAR2, colon cancer, epigenetics, HDAC, butyrate

Introduction

Free fatty acid receptor 2 (FFAR2, also known as GPR43) belongs to the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family1. GPCRs span the cell membrane seven times, and they signal via heterotrimeric G proteins of α and βγ subunits to activate various downstream effectors1. FFAR2 is activated by short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, that are produced when gut bacteria ferment dietary fiber1. Activated FFAR2 couples to the Gαi pathway to inhibit cAMP signaling, and to the Gαq pathway to promote calcium mobilization1. cAMP signaling dampened by FFAR2 then suppresses protein kinase A (PKA, a primary downstream effector of cAMP) and its substrate, cAMP response element binding protein (CREB). The net result is a decrease in histone deacetylase (HDAC) expression2. SCFAs, which are naturally occurring ligands for FFAR2, suppress class I HDACs (HDAC1, 2, 3, 8) and class IIa HDACs (HDAC4, 5, 7, 9)3, 4. The two major signaling mechanisms of SCFA-mediated functions are inhibition of HDACs and activation of GPCRs5.

FFAR2 expression is higher in normal colonic epithelium and neutrophils than in other immune cells6, 7. Several lines of evidence suggest that FFAR2 is an important regulator of colonic inflammation. Stimulation of FFAR2 by SCFAs is necessary for normal resolution of certain inflammatory responses, because FFAR2-deficient mice showed exacerbated inflammation in a colitis model7. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) that express the transcription factor Foxp3 are critical for regulating intestinal inflammation6. FFAR2-deficient mice exhibit a larger and dysfunctional Treg pool, and they developed more severe colitis6. Compared with wild-type (WT) mice, dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-treated FFAR2-deficient mice had significantly worsened colonic inflammation, and higher levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 17 (IL-17) protein in their colonic mucosa8. In addition, dysregulated inflammasome contributed to exacerbated colitis in the FFAR2-deficient mice9. Accordingly, these studies suggest that FFAR2 plays a crucial role in suppressing colonic inflammation. However, it remains unclear whether FFAR2 acts as an epigenetic regulator that protects against colon carcinogenesis.

The mechanisms by which histone modifications and DNA methylation suppress gene transcription have been elucidated10. Methylated CpG islands form binding sites for proteins, such as MeCp2, that bind to methylated DNA. Binding to MeCp2 is followed by recruitment of a protein complex that includes HDACs. This process ultimately leads to a closed chromatin configuration that excludes transcription factors. Evidence suggests that histone H3 lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me) and H3K27 tri-methylation (H3K27me3) are critical histone modifications that associate with closed chromatin at DNA methylation sites10.

In the current study, we slightly irritated colon by only using overnight DSS treatment and successfully promoted 100% colon tumor incidence in the ApcMin/+ mice and the azoxymethane (AOM)-treated mice on C57/B6 background11. These models mimic mild inflammation in human colorectal cancer. We investigated the role of FFAR2 in colon adenoma development in the ApcMin/+/DSS mice. We also assessed whether loss of FFAR2 promoted the progression of adenoma to adenocarcinoma in the AOM/DSS mice. We found that loss of FFAR2 promoted the development of colon adenoma and the progression of adenoma to adenocarcinoma. FFAR2 deficiency led to enhanced downstream cAMP–PKA–CREB pathway, which resulted in overexpression of HDACs and epigenetically decreased levels of inflammation suppressors.

Materials and Methods

Animals and reagents

All the animal protocols followed the institutional guidelines for animal care and were approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Animal Care and Use Committee. Breeding pairs of the ApcMin/+ mice (C57/B6 background) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and breeding pairs of the FFAR2 heterozygous (FFAR2+/−) mice (C57/B6 background) were purchased from Deltagen, Inc. (San Mateo, CA). FFAR2 homozygous (FFAR2−/−) mice were produced by breeding FFAR2+/− mice. ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/− mice were generated by first breeding ApcMin/+ mice with FFAR2−/− mice to generate ApcMin/+-FFAR2+/− mice and then breeding ApcMin/+-FFAR2+/− mice with FFAR2−/− mice.

Azoxymethane (AOM) and butyrate were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and dextran sodium sulfate (DSS, 36,000–50,000 M.W.) was obtained from MP Biochemicals (Santa Ana, CA).

Animal experiments

Four- to five-week-old ApcMin/+ and ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/− mice were given 5% DSS in their drinking water overnight. Six weeks after the DSS treatment, all the ApcMin/+ and ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/− mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. Colonic polyp number and size were determined. Five- to six-week-old WT mice and FFAR2−/− mice received an i.p. injection of AOM (15 mg/kg, body weight). One week after the injection, mice were given 5% DSS in their drinking water overnight. Six weeks after the DSS treatment, all the WT and FFAR2−/− mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. Colonic polyp number and size were determined.

Colons collected from all the mice were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin (FFPE). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed, and our pathologists examined the tissue sections.

Depletion of neutrophils

Two weeks after the DSS treatment, subgroups of the ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/− mice were injected i.p. with anti-GR-1 antibodies (0.1mg/mouse, Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH) once per week for four weeks. Depletion of neutrophils was confirmed by flow cytometry in splenocytes of the ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/− mice.

Immunohistochemistry

FFPE colon tissue blocks were cut into 4 μm sections, and immunohistochemistry was conducted as previously described12, 13. A Dako Autostainer was used to stain the slides with primary antibodies to PKA (phospho S99) (1:1000, ab32390), CREB (phospho S133) (1:500, ab32096), and GR-1 (1:50, ab2557) from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); antibodies to cAMP (1:250, LS-C121425) from LifeSpan Biosciences (Seattle, WA); antibodies to HDAC2 (1:100, sc-7899) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas); antibodies to HDAC4 (1:800, NBP2-22151) from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO); and antibodies to Ki67 (1:300, 12202) from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Stained slides were photographed at 20 x magnification, and only the staining in the adenoma and adenocarcinoma area was quantified, as previously described12, 13.

Isolation of colonic lamina propria

Colonic lamina propria (LP) was prepared using a Dissociation Kit (130-097-410) from Miltenyi Biotec (San Diego, CA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, colon specimens were collected, open longitudinally, and cut into short segments. All the segments were incubated in pre-digestion solution at 37°C for 20 min twice, followed by incubation in HBSS without calcium. Then all the segments were incubated in pre-heated digestion solution with enzyme mix at 37°C for 30 min. The gentle MACs dissociator (m_intestine_01 program) was run to mechanically brake down tissue segments. Samples were centrifuged and the pellet was re-suspended in RPMI 1640 medium for further application13.

Isolation of colonic epithelium

Two weeks after the DSS treatment, subgroups of the WT and FFAR2−/− mice, were euthanized by CO2. Colonic epithelium was prepared by incubation with chelating agents (PBS containing 20 mM EDTA) as previously described14.

Butyrate treatment

Colonic epithelium and colonic LP were prepared and cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS. These cultured cells were treated with 5 mM butyrate for 16 hrs. The cells were collected for further application.

Flow cytometry

The samples were first stained with CD45 and GR-1 antibodies (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Then the samples were fixed and permeabilized by Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences). The samples were stained with IL-1, IL-6, and TNF antibodies (BD Biosciences). The samples were analyzed on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and the results were analyzed using the FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation-Quantitative PCR analysis (ChIP-qPCR)

Chromatin in colonic LP samples was immunoprecipitated, using a ChIP-IT High Sensitivity Kit (53040) from Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sonicated chromatin was incubated overnight with antibodies to H3K27me3 (ab6002) and H3K4me3 (ab8580) from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Quantitative PCR analysis was performed following the ChIP assay, and the percentage enrichment of the input was analyzed on the promoter regions of gapdh, sfrp1, sox17, dkk2, dkk3, vdr, adh1, and socs1 genes. Primer information is provided in Supplementary Table 1A.

Quantitative PCR analysis

We extracted RNA from FFPE mouse colon tissues, using the RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit for formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues (Ambion, Grand Island, NY). RNA from butyrate-treated colonic epithelium and colonic LP samples were extracted using AllPrep® DNA/RNA/Protein Mini kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). Total RNA was reverse-transcribed using Superscript III RT (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), and quantitative PCR procedures were performed. Primer information is provided in Supplementary Table 1B.

Pyrosequencing

Genomic DNA from butyrate-treated colonic epithelium and colonic LP samples were extracted using AllPrep® DNA/RNA/Protein Mini kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). 500 ng of the genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite, and purified using the EZ DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). Bisulfite-treated DNA was amplified with specific primers of sox17 and socs1 genes. Primer information is provided in Supplementary Table 1C. A Pyrosequencing system (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used to measure methylated CpG sites on the promoter regions of sox17 and socs1 genes. Average methylation levels of individual CpG sites for each DNA sample were calculated, and the results are presented as percentage methylation.

Statistical analysis

Using SigmaPlot (Systat Software, San Jose, CA), we performed unpaired two-tail Student t-tests to compare the ApcMin/+/DSS mice with ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice and AOM/DSS-treated WT mice with FFAR2−/− mice. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

FFAR2 deficiency promoted the development of colon adenomas and the progression of adenoma to adenocarcinoma, and enhanced the downstream cAMP–PKA–CREB–HDAC pathway

We successfully manipulated the dose and duration of DSS treatment to only slightly irritate colon, which mimic the mild inflammation that promotes the development of adenomas and adenocarcinoma in human colon 11. Four- to five-week-old ApcMin/+ mice and ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/− mice were exposed to 5% DSS overnight (Figure 1A). Six weeks after the DSS treatment, 100% mice had developed colon lesions. The ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/− mice that treated with DSS (ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS) had significantly more and larger lesions and a higher percentage of high-grade dysplastic adenomas than the ApcMin/+ mice with DSS treatment (ApcMin/+/DSS) (Figure 1B), suggesting that FFAR2 deficiency promotes the progression of low-grade dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia. Further, we stained the colon tissues to investigate if knocking out FFAR2 influences its downstream cAMP pathway. In the colon adenomas of the ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice, staining for cAMP–PKA–CREB–HDAC signaling and the proliferative marker Ki67 was enhanced compared to those of the ApcMin/+/DSS mice (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. FFAR2 deficiency promoted the development of adenomas and the progression of adenoma to adenocarcinoma, and enhanced the downstream cAMP–PKA–CREB–HDAC pathway.

(A) The ApcMin/+ (n=15) and ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/− (n=15) mice were treated with 5% DSS overnight and were euthanized 6 weeks after the DSS treatment. (B) The ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice developed more and larger lesions that showed high-grade dysplastic features. (C) Staining of cAMP–PKA–CREB–HDAC signaling, proliferative marker (Ki67) and GR-1 neutrophil in colon adenoma was enhanced in colon of the ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice (ApcMin/+: n=4–5, ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−: n=4–5). (D) Wild-type (WT) (n=15) and FFAR2−/− (n=15) mice were treated with one dose of AOM (15mg/kg body weight, i.p.) followed by 5% DSS overnight. Six weeks after receiving DSS, all the mice were euthanized. (E) The FFAR2−/− mice had more and larger tumors and a larger percentage of intramucosal adenocarcinoma. (F) Staining of cAMP–PKA–CREB–HDAC signaling, proliferative marker (Ki67) and GR-1 neutrophil in colon adenoma and adenocarcinoma was enhanced in colon of the AOM/DSS-treated FFAR2−/− mice (WT: n=3, FFAR2−/−: n=3). LGD: low-grade dysplasia; HGD: high-grade dysplasia: IMC: intramucosal adenocarcinoma. * p <0.05.

In another model, we also examined the role of FFAR2 in the progression of colon adenoma to carcinoma that results from mild inflammation caused by AOM and overnight DSS treatment. We first injected 5- to 6-week-old WT and FFAR2−/− mice (on the C57/B6 background) with one dose of AOM (15 mg/kg, body weight) and then treated them with 5% DSS overnight (Figure 1D). The FFAR2−/− mice had significantly more and larger lesions in the colon, and a higher percentage of them developed intramucosal adenocarcinoma (Figure 1E), as well as overexpressed cAMP–PKA–CREB–HDAC signaling and Ki67 staining (Figure 1F) compared with the WT mice. Together, these results indicate that FFAR2 protects against colon carcinogenesis. In the absence of FFAR2, the downstream cAMP–PKA–CREB–HDAC signaling was enhanced, which contributed to the increased proliferation.

FFAR2 deficiency disrupted neutrophil homeostasis in colonic lamina propria

FFAR2 has a higher expression in neutrophils than other immune cells. We further investigate if FFAR2 deficiency influences neutrophil homeostasis. We stained the colon tissues with anti-GR-1 antibodies to determine the neutrophil infiltration, and measured the neutrophil population and its cytokine production by flow cytometry. We observed a significantly increased neutrophil infiltration to colon adenomas (Figure 1C) and a higher neutrophil population in colonic LP of the ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice compared to ApcMin/+/DSS mice (Figures 2A–B and Supplementary Figure 1A). In addition, the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were significantly enhanced by FFAR2 deficiency (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure 1A). We further depleted neutrophils by injecting anti-GR-1 antibodies to the ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice (Figure 2C) and confirmed the depletion in splenocytes by flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure 1B). Neutralization of neutrophils significantly decreased the number and size of colon tumors driven by FFAR2 deficiency (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. FFAR2 deficiency disrupted neutrophil homeostasis in colonic lamina propria.

(A) The ApcMin/+ and ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/− mice were treated with 5% DSS overnight and were euthanized 6 weeks after the DSS treatment. (B) Percentages of colonic LP neutrophils and cytokines were measured by flow cytometry (ApcMin/+: n=16, ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−: n=6). (C) Two weeks after the DSS treatment, ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/− mice were given anti-GR-1 antibodies (GR-1 Ab) once per week for 4 weeks. (D) Depletion of neutrophils by GR-1 Ab suppressed colon lesions in the ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice (Ctrl: n=15, GR-1 Ab: n=5). (E) The wild-type (WT) and FFAR2−/− mice were treated with one dose of AOM (15mg/kg body weight, i.p.) followed by 5% DSS overnight, and were euthanized 6 weeks after the DSS treatment. (F) Percentages of colonic LP neutrophils and cytokines were measured by flow cytometry (WT: n=7, FFAR2−/−: n=4). * p <0.05.

Similarly, we observed an increased infiltration of neutrophils in adenomas and adenocarcinomas of the AOM/DSS-treated FFAR2−/− mice (Figure 1F). However, the levels of colonic LP neutrophils, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α remained unchanged between the WT mice and the FFAR2−/− mice (Figures 2E–F and Supplementary Figure 1A).

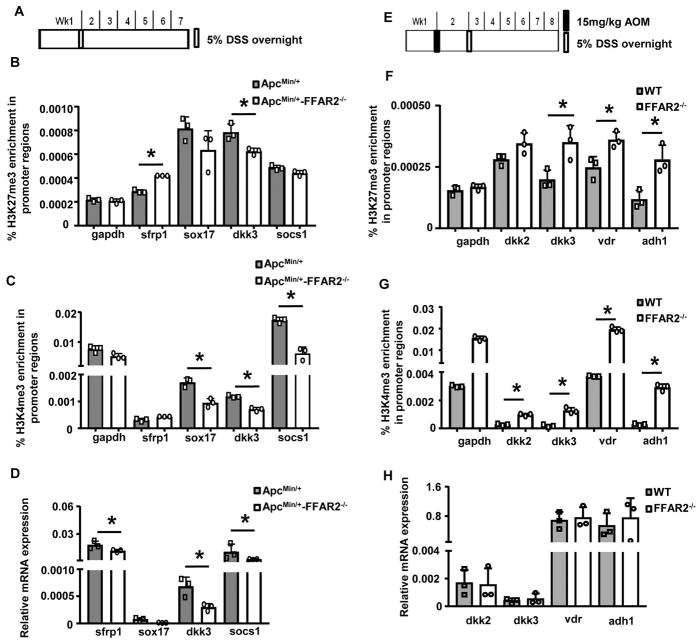

FFAR2 deficiency changed histone modification on the inflammation regulators

Since we observed overexpression of HDACs in the FFAR2-deficient mice (Figure 1), we then studied epigenetic changes induced by loss of FFAR2 in the inflammation regulators. Colonic LP from the ApcMin/+/DSS mice and ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice was analyzed by ChIP-qPCR (Figure 3A). Binding of H3K27me3, a suppressive histone mark, was enhanced on the promoter regions of sfrp1 in colonic LP of the ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice (Figure 3B). In contrast, binding of H3K4me3, an active histone mark, were lower on the promoter regions of sox17, dkk3, and socs1 in colonic LP of the ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice (Figure 3C). mRNA expression of sfrp1, dkk3, and socs1 was significantly decreased in colon of the ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice (Figure 3D). These results suggest that loss of FFAR2 decreased the expression of inflammation suppressors through changing histone marks on their promoter regions.

Figure 3. FFAR2 deficiency changed histone modification on inflammation regulators.

(A) The ApcMin/+ and ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/− mice were treated with 5% DSS overnight and were euthanized 6 weeks after the DSS treatment. ChIP-qPCR analysis of H3K27me3 (B) and H3K4me3 (C) on the promoter regions of inflammation suppressors (triple technique repeats were shown), and mRNA expression of those genes (D) from colonic LP of the ApcMin/+/DSS and ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice. (E) The wild-type (WT) and FFAR2−/− mice were treated with one dose of AOM (15mg/kg body weight, i.p.) followed by 5% DSS overnight, and were euthanized 6 weeks after the DSS treatment. ChIP-qPCR analysis of H3K27me3 (F) and H3K4me3 (G) on the promoter regions of inflammation suppressors (triple technique repeats were shown), and mRNA expression of those genes (H) from colonic LP of the AOM/DSS-treated WT and FFAR2−/− mice (n=3). * p <0.05.

We also examined epigenetic changes of the inflammation regulators in the AOM/DSS model (Figure 3E). Interestingly, binding of both H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 was enriched on the promoter regions of dkk2, dkk3, vdr, and adh1, which are inflammation suppressors15, 16 (Figures 3F–G). Despite the overexpression of HDACs in the FFAR2−/− mice (Figure 1F), gene expression of these inflammation suppressors was not changed (Figure 3H).

FFAR2 was required for butyrate to function in colonic epithelium and colonic lamina propria

To determine if the FFAR2 pathway became dysregulated, we isolated the colonic epithelium and LP from the AOM/DSS-treated WT and FFAR2−/− mice 2 weeks after the DSS treatment (Figure 4A). We cultured the epithelium and LP with or without 5 mM butyrate for 16 hr, and then harvested the cells. We used butyrate, a ligand for FFAR2, to determine the ligand-receptor axis in the cultured colonic epithelium and LP. Our results showed that mRNA expression of hdac2 in the colonic epithelium (Figure 4B) and LP (Figure 4C) was higher in the FFAR2−/− mice. It was decreased by butyrate only in the WT mice (Figures 4B–C), suggesting that FFAR2 needs to be present for the ligand to function. For inflammation suppressor sox17 and socs115, 17, mRNA expression was lower and DNA methylation of the promoters was higher in the FFAR2−/− mice (Figures 4B–C). Consistent with hdac2, butyrate lost its ability to modulate sox17 and socs1 in the colonic epithelium and LP from the FFAR2−/− mice (Figures 4B–C). Furthermore, butyrate decreased the percentage of neutrophils and IL-1β levels in colonic LP from the WT mice but not the FFAR2−/− mice (Figure 4D and Supplementary Figure 2). These results again suggest that loss of FFAR2 impairs butyrate’s protective effects.

Figure 4. FFAR2 was required for butyrate to function in colonic epithelium and colonic LP.

(A) The wild-type (WT) and FFAR2−/− mice were treated with one dose of AOM (15 mg/kg body weight, i.p.) followed by 5% DSS overnight, and were euthanized two weeks after the DSS treatment. Colonic epithelium and LP were isolated from these mice and cultured with or without 5 mM butyrate for 16 hr. mRNA expression of hdac2, sox17, and socs1 and promoter DNA methylation of sox17 and socs1 in colonic epithelium (B) and colonic LP (C) (WT: n=6, FFAR2−/−: n=6). (D) Percentage of neutrophils and IL-1β levels in colonic LP were measured by flow cytometry (WT: n=7–8, FFAR2−/−: n=4). * p <0.05.

Discussion

The fatty acid receptor family has several members, such as FFAR1 (GPR40), FFAR2 (GPR43), FFAR3 (GPR41), GPR84 and GPR120. FFAR1 and GPR120 respond to long-chain fatty acids; GPR84 is activated by medium-chain fatty acids18; while FFAR2 and FFAR3, sharing 43% of their amino acids in common, are the two main receptors for SCFAs19. FFAR3 is expressed in adipose tissue, while FFAR2 is highly expressed in colonic epithelial cells20, colonic neutrophils and monocytes21, 22. FFAR2 has been reported to be involved in colonic inflammation23, 24. However, it remains to be elucidated whether FFAR2 is an epigenetic regulator that suppresses colon tumorigenesis. Our results support the idea that FFAR2 suppresses tumor progression in an epigenetic manner in both the ApcMin/+/DSS and the AOM/DSS models. FFAR2 deficiency led to overexpression of its downstream cAMP–PKA–CREB–HDAC signaling, which epigenetically dysregulated inflammation suppressors. Our results also showed that neutrophil population in the colonic LP was increased when FFAR2 was knocked out in the ApcMin/+/DSS model. Infiltration of neutrophils into adenomas and adenocarcinomas was increased in the FFAR2-deficient mice. These results suggest that FFAR2 is important for colon neutrophil homeostasis. More importantly, our results suggest that FFAR2 is a tumor suppressor that blocks progression of low-grade dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia and further to adenocarcinoma.

It should be noted that loss of FFAR2 may affect neutrophil homeostasis and histone modification differently at different stages of colon carcinogenesis. Loss of FFAR2 led to the infiltration of neutrophils in colon tumors in both the ApcMin/+/DSS and the AOM/DSS mice. Interestingly, knocking out FFAR2 increased the percentage of neutrophils and levels of cytokines in colonic LP from the ApcMin/+/DSS mice but not in colon from the AOM/DSS mice. These results suggest that neutrophil trafficking induced by FFAR2 deficiency differs at different stages of colon carcinogenesis.

Suppressor genes sfrp1 and dkk3 are key inhibitors in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Our previous studies using DSS-induced colitis model showed hypermethylation of the promoter region of sfrp1 and dkk3, suggesting their protective role against colon inflammation25. Consistently, sfrp1 and dkk3 were hypermethylated in human CRC26, 27 and in ApcMin/+ mice28. Overexpression of DKK3 suppressed proliferation and invasion, induced apoptosis, and reduced the β-catenin accumulation in colon cancer cells29. In addition, SOCS1 is a suppressor of cytokine signaling, and it has been reported to inhibit the reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of colon cancer cells30. Overexpression of SOCS1 increased the mir-200 family of miRNAs, which promotes the mesenchymal–epithelial transition and reduces tumor migration in colon cancer cells31. These studies demonstrated the crucial role of sfrp1, dkk3 and socs1 in gut inflammation and colon carcinogenesis. Our current study demonstrated that FFAR2 deficiency induced differential modifications of H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 on the promoter regions of these inflammation suppressors in colonic LP from both models. Histone modifications correlated better with mRNA expression of inflammation suppressors in the ApcMin/+/DSS model than in the AOM/DSS model. Despite FFAR2-deficiency enriched binding of both H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 to multiple inflammation suppressors in the AOM/DSS model, mRNA expression of these genes remained unchanged. Therefore, it is possible that these genes are not regulated by histone modifications in the AOM/DSS model. Furthermore, other histone modifications could affect gene expression. For example, enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), the functional enzymatic component of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), has been shown to directly transfer methyl groups onto H3K2732, in turn to silence gene expression. One group observed that HDAC inhibitors prevented the transfer of methyl groups by PRC2 on the promoter region of tumor suppressor gene E-cadherin, which led to increased expression of E-cadherin33. Though we did not observe significant change of the overall ezh2 mRNA expression in the FFAR2-deficient mice (Supplementary Figure 3), whether EZH2-containing PRC2 regulates the H3K27me3 levels on the promotor regions of inflammation suppressors (sfrp1, dkk3, and socs1) in the FFAR2-deficient mice needs further investigation.

SCFAs play essential roles in colonic heath and integrity. For example, butyrate is the major and preferred energy source for colonocytes34. SCFAs also regulate colonic mobility, colonic blood flow, and gastrointestinal pH that affects uptake and absorption of electrolytes and nutrients35. In addition, SCFAs act on host immune system to elicit anti-inflammatory and anti-tumorigenic effects36, 37. The two major signaling mechanisms of SCFAs are inhibition of HDACs and activation of GPCRs5. SCFAs mediated their anti-tumor effects, including inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and inducing apoptotic cell death, through activating FFAR2 receptors in human colon cancer cells38, suggesting that FFAR2 functions as a tumor suppressor in colon cancer cells. Consistently, our previous study13 and the results from current study also indicate that FFAR2 plays a tumor suppressor role in the mouse models of colon cancer. Furthermore, studies have shown that SCFAs can cross the mucosa by active transports, such as the monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT-1) and the sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transporter 1 (SMCT-1), and inhibit HDACs independent of FFAR239, 40. These transporters are highly expressed on colonocytes and along the GI tract41, and MCT-1 has high expression on lymphocytes42. Therefore, it is possible that both absorption-mediated and FFAR2-mediated HDAC inhibition by SCFAs occur within the same cell. We further knocked down ffar2 in SW480 and HT29 cells, which have relatively higher levels of FFAR2 expression (Supplementary Figures 4A–B) and measured their HDAC activities upon butyrate treatment. Interestingly, we observed higher levels of HDAC activities in ffar2-knock-down SW480 cells at the baseline (Supplementary Figure 4C), which is consistent with enhanced HDAC expression in our FFAR2-deficient mice. However, butyrate induced similar dose-dependent inhibition of HDAC activities in both ffar2-intact and ffar2-knock-down SW480 cells. These results suggest both absorption-mediated and FFAR2-mediated HDAC inhibition by butyrate occur in SW480 cells. By contrast, we did not find significant effects on HDAC activities of HT29 cells by either FFAR2 or butyrate treatment (Supplementary Figure 4C), though other group observed suppressed HDAC activities by butyrate in HT29 cells using nuclear extracts43.

Recent data suggest that FFAR2 and FFAR3 can form heterodimer, which showed enhanced calcium signaling, lost the ability to inhibit cAMP signaling, but obtained the function to phosphorylate p38 pathway44. Though the authors did not observe FFAR2-FFAR3 heterodimers in human colon epithelial cells44, we cannot exclude that loss of FFAR2-FFAR3 heterodimer-mediated activities might also contribute to our findings in FFAR2 single knock-out mice. Interestingly, we observed decreased mRNA levels of ffar3 in the FFAR2-deficient mice in the ApcMin/+/DSS model (Supplementary Figure 5), while other group found no changes of ffar3 in the FFAR2-deficient mice45. Therefore, the reduced expression of ffar3 may also contribute to our observed tumor-promoting effects in the FFAR2-deficient mice. Furthermore, human colon cancer patients have decreased ffar3 mRNA levels when compared to healthy individuals46, suggesting its possible tumor suppressor role. The ffar3 gene has very limited CpG islands, suggesting that the epigenetic changes induced by loss of FFAR2 may not directly influence the ffar3 mRNA expression. The mechanism of decreasing ffar3 mRNA expression in the FFAR2-deficient mice of ApcMin/+/DSS model warrants further investigation.

Our results showed that colonic epithelium and colonic LP from the AOM/DSS-treated FFAR2−/− mice do not respond to butyrate, suggesting that FFAR2 is essential for butyrate to function. Loss of FFAR2 led to overexpression of HDACs, which then epigenetically dysregulated inflammation suppressors, promoting the progression of colon adenoma to adenocarcinoma.

Our studies suggest that FFAR2 deficiency impairs homeostasis of neutrophils that promote colon cancer. Because cancer immunology involves different immune cells that function together to control immune surveillance, we asked if levels of other immune cell types were affected by loss of FFAR2. There was no change in CD8+ T cells or CD19+ B cells, but NKp46+ natural killer (NK) cells were lower and CD4+ T cells were higher in the splenocytes of the ApcMin/+-FFAR2−/−/DSS mice than in those of the ApcMin/+/DSS mice (Supplementary Figure 6). NK cells play a critical surveillance role in cancers, including colorectal cancer47. In cancer, inducible or adaptive Treg expand, accumulate in tissues and the peripheral blood of patients, and are a functionally prominent component of CD4+ T lymphocytes. Inducible Treg can produce prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and expand in response to tumor antigens and cytokines such as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) or IL-10, which are presumed to be responsible for suppressing anti-tumor immune responses and successful tumor escape48. Because FFAR2 expression is higher in neutrophils than in other immune cells6, we speculate that loss of FFAR2 will have a greater impact on neutrophil function. Indeed, infiltration of neutrophils into colonic LP and colon lesions was enhanced in the FFAR2-deficient mice. However, the decrease in NK cells and increase in CD4+ T cells undoubtedly contributed to colon tumor development in the knock-out mice as well. Whether unbalanced neutrophil homeostasis then suppresses NK cells and promotes CD4+ T cells in the FFAR2-deficient mice warrants further investigation.

It also should be noted that studies of FFAR2 and colon inflammation suggest both protective and causative roles49. For example, in DSS-induced mouse colitis models, FFAR2 knock-out promoted colon inflammation after either 2.5% DSS for 7 days7 or 2% DSS for 7 days8, suggesting an anti-inflammatory role for FFAR2. By contrast, a study that used 4% DSS for 6 days to induce colon colitis reported that FFAR2 knockout suppressed colon inflammation, suggesting a pro-inflammatory role of FFAR250. Therefore, even using the same chemical to induce colitis can give dramatically different results, though the reasons for this discrepancy remain to be determined. It is possible that bacteria in different housing environments and the animals could contribute to the degree of colon inflammation induced by DSS. It is also possible that FFAR2 plays different roles with different degrees of inflammation. These results should be interpreted with caution.

Our current study assessed whether FFAR2 deficiency drives the progression of colon cancer that is promoted by mild-inflammation. Our results suggest that FFAR2 is an important epigenetic tumor suppressor that blocks colon cancer progression (Figure 5). The downstream pathway of FFAR2, cAMP–PKA–CREB signaling, was overexpressed in the FFAR2-deficient mice, leading to overexpression of HDACs. Consequently, inflammation suppressors were hypermethylated, and their expression levels were decreased. Accordingly, our findings support the hypothesis that FFAR2 is a novel biomarker for colon cancer progression.

Figure 5. Loss of FFAR2 epigenetically promotes colon cancer.

SCFAs bind to and activate FFAR2, which inhibits its downstream cAMP–PKA–CREB–HDAC pathway. SCFAs also can be transported across cell membrane to inhibit HDAC activities. Loss of FFAR2 results in enhanced cAMP–PKA–CREB pathway and overexpressed HDAC. The expression levels of inflammation suppressors, such as sfrp1, dkk3, and socs1, were decreased, which promote the progression of colon carcinogenesis. However, absorption-mediated HDAC inhibition by SCFAs could still occur in FFAR2-deficient cells.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Impact.

Loss of FFAR2 epigenetically promoted the development of colon cancer in two mouse models. In the FFAR2-deficient mice, the downstream cAMP–PKA–CREB–HDAC pathway was enhanced. H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 histone marks differentially bound onto the promoter regions of inflammation suppressors, resulting in their lower expression. More neutrophils infiltrated into tumors and colonic lamina propria. FFAR2 is required for butyrate, a natural ligand of FFAR2, to suppress HDAC expression and hypermethylation of inflammation suppressors.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This project was supported in part by a NIH grant 5 R01 CA148818 (to L.-S. Wang) and an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant RSG-13-138-01-CNE (to L.-S. Wang). This project was also supported in part by a NIH grant 5 R01 CA185301 (to J.Y.) and an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant RSG-14-243-01-LIB (to J.Y.).

Abbreviations

- AOM

azoxymethane

- CREB

cAMP response element binding protein

- DSS

dextran sodium sulfate

- EZH2

enhancer of zeste homolog 2

- FFAR2

free fatty acid receptor 2

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- H3K9me

histone H3 lysine 9 methylation

- H3K27me3

H3K27 tri-methylation

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- IL-17

interleukin 17

- MCT-1

monocarboxylate transporter 1

- NK

natural killer

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PRC2

polycomb repressive complex 2

- SCFAs

short-chain fatty acids

- SMCT-1

sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transporter 1

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor beta

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Competing Interests:

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Contributions:

Study design, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data: Pan Pan, Kiyoko Oshima, Yi-Wen Huang, Kimberle Agle, William Drobyski, Xiao Chen, Jianying Zhang, Martha Yearsley, Jianhua Yu and Li-Shu Wang.

Manuscript writing and revising: Pan Pan, Jianhua Yu and Li-Shu Wang.

Final approval: Li-Shu Wang and Jianhua Yu.

Contributor Information

Pan Pan, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Kiyoko Oshima, Department of Pathology, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Yi-Wen Huang, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Kimberle A. Agle, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA

William R. Drobyski, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA

Xiao Chen, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Jianying Zhang, Center for Biostatistics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Martha M. Yearsley, Department of Pathology, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA

Jianhua Yu, Division of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Comprehensive Cancer Center and The James Cancer Hospital, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

Li-Shu Wang, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, RM C4930, 8701 Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI, 53226, USA.

References

- 1.Lee T, Schwandner R, Swaminath G, Weiszmann J, Cardozo M, Greenberg J, Jaeckel P, Ge H, Wang Y, Jiao X, Liu J, Kayser F, et al. Identification and functional characterization of allosteric agonists for the G protein-coupled receptor FFA2. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1599–609. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shao RH, Tian X, Gorgun G, Urbano AG, Foss FM. Arginine butyrate increases the cytotoxicity of DAB389IL-2 in leukemia and lymphoma cells by upregulation of IL-2Rβ gene. Leuk Res. 2002;26:1077–83. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakshmaiah KC, Jacob LA, Aparna S, Lokanatha D, Saldanha SC. Epigenetic therapy of cancer with histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10:469–78. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.137937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajendran P, Williams DE, Ho E, Dashwood RH. Metabolism as a key to histone deacetylase inhibition. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;46:181–99. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2011.557713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan J, McKenzie C, Potamitis M, Thorburn AN, Mackay CR, Macia L. The role of short-chain fatty acids in health and disease. Adv Immunol. 2014;121:91–119. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800100-4.00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly-Y M, Glickman JN, Garrett WS. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341:569–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, Kranich J, Sierro F, Di Y, Schilter HC, Rolph MS, Mackay F, Artis D, Xavier RJ, Teixeira MM, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461:1282–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masui R, Sasaki M, Funaki Y, Ogasawara N, Mizuno M, Iida A, Izawa S, Kondo Y, Ito Y, Tamura Y, Yanamoto K, Noda H, et al. G protein-coupled receptor 43 moderates gut inflammation through cytokine regulation from mononuclear cells. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2848–56. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000435444.14860.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macia L, Tan J, Vieira AT, Leach K, Stanley D, Luong S, Maruya M, Ian McKenzie C, Hijikata A, Wong C, Binge L, Thorburn AN, et al. Metabolite-sensing receptors GPR43 and GPR109A facilitate dietary fibre-induced gut homeostasis through regulation of the inflammasome. Nat Commun. 2015:6. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones PL, Wolffe AP. Relationships between chromatin organization and DNA methylation in determining gene expression. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:339–47. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1999.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan P, Kang S, Wang Y, Liu K, Oshima K, Huang Y-W, Zhang J, Yearsley M, Yu J, Wang L-S. Black Raspberries Enhance Natural Killer Cell Infiltration into the Colon and Suppress the Progression of Colorectal Cancer. Frontiers in Immunology. 2017:8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan P, Skaer CW, Wang HT, Stirdivant SM, Young MR, Oshima K, Stoner GD, Lechner JF, Huang YW, Wang LS. Black raspberries suppress colonic adenoma development in ApcMin/+ mice: relation to metabolite profiles. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:1245–53. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan P, CWS, Wang HT, Oshima K, Huang YW, Yu J, Zhang J, MMY, KAA, WRD, Chen X, Wang LS. Loss of free fatty acid receptor 2 enhances colonic adenoma development and reduces the chemopreventive effects of black raspberries in ApcMin/+ mice. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38:86–93. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossmann J, Walther K, Artinger M, Kiessling S, Steinkamp M, Schultz M, Scholmerich J, Rogler G. Progress on isolation and short term culture of primary human intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) Gastroenterology. 2002;122:A373-A. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L-S, Kuo C-T, Stoner K, Yearsley M, Oshima K, Yu J, Huang TH-M, Rosenberg D, Peiffer D, Stoner G, Huang Y-W. Dietary black raspberries modulate DNA methylation in dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced ulcerative colitis. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2842–50. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abu-Remaileh M, Bender S, Raddatz G, Ansari I, Cohen D, Gutekunst J, Musch T, Linhart H, Breiling A, Pikarsky E, Bergman Y, Lyko F. Chronic inflammation induces a novel epigenetic program that is conserved in intestinal adenomas and in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2120–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng C, Huang C, Ma T-T, Bian E-B, He Y, Zhang L, Li J. SOCS1 hypermethylation mediated by DNMT1 is associated with lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory cytokines in macrophages. Toxicol Lett. 2014;225:488–97. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulven T. Short-chain free fatty acid receptors FFA2/GPR43 and FFA3/GPR41 as new potential therapeutic targets. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012;3:111. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown AJ, Goldsworthy SM, Barnes AA, Eilert MM, Tcheang L, Daniels D, Muir AI, Wigglesworth MJ, Kinghorn I, Fraser NJ, Pike NB, Strum JC, et al. The Orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11312–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bindels LB, Dewulf EM, Delzenne NM. GPR43/FFA2: physiopathological relevance and therapeutic prospects. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34:226–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nilsson NE, Kotarsky K, Owman C, Olde B. Identification of a free fatty acid receptor, FFA2R, expressed on leukocytes and activated by short-chain fatty acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303:1047–52. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00488-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masui R, Sasaki M, Funaki Y, Ogasawara N, Mizuno M, Iida A, Izawa S, Kondo Y, Ito Y, Tamura Y, Yanamoto K, Noda H, et al. G protein-coupled receptor 43 moderates gut inflammation through cytokine regulation from mononuclear cells. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2013;19:2848–56. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000435444.14860.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim MH, Kang SG, Park JH, Yanagisawa M, Kim CH. Short-chain fatty acids activate GPR41 and GPR43 on intestinal epithelial cells to promote inflammatory responses in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:396–406. e1–10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macia L, Tan J, Vieira AT, Leach K, Stanley D, Luong S, Maruya M, Ian McKenzie C, Hijikata A, Wong C, Binge L, Thorburn AN, et al. Metabolite-sensing receptors GPR43 and GPR109A facilitate dietary fibre-induced gut homeostasis through regulation of the inflammasome. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6734. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang LS, Kuo CT, Stoner K, Yearsley M, Oshima K, Yu J, Huang TH, Rosenberg D, Peiffer D, Stoner G, Huang YW. Dietary black raspberries modulate DNA methylation in dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced ulcerative colitis. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2842–50. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galamb O, Kalmar A, Peterfia B, Csabai I, Bodor A, Ribli D, Krenacs T, Patai AV, Wichmann B, Bartak BK, Toth K, Valcz G, et al. Aberrant DNA methylation of WNT pathway genes in the development and progression of CIMP-negative colorectal cancer. Epigenetics. 2016;11:588–602. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1190894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugai T, Yoshida M, Eizuka M, Uesugii N, Habano W, Otsuka K, Sasaki A, Yamamoto E, Matsumoto T, Suzuki H. Analysis of the DNA methylation level of cancer-related genes in colorectal cancer and the surrounding normal mucosa. Clin Epigenetics. 2017;9:55. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0352-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Y, Lee JH, Shu L, Huang Y, Li W, Zhang C, Yang AY, Boyanapalli SS, Perekatt A, Hart RP, Verzi M, Kong AT. Association of aberrant DNA methylation in Apc(min/+) mice with the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and Wnt/beta-catenin pathways: genome-wide analysis using MeDIP-seq. Cell Biosci. 2015;5:24. doi: 10.1186/s13578-015-0013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang ZR, Dong WG, Lei XF, Liu M, Liu QS. Overexpression of Dickkopf-3 induces apoptosis through mitochondrial pathway in human colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1590–601. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i14.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung SH, Kim SM, Lee CE. Mechanism of suppressors of cytokine signaling 1 inhibition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition signaling through ROS regulation in colon cancer cells: suppression of Src leading to thioredoxin up-regulation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:62559–71. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.David M, Naudin C, Letourneur M, Polrot M, Renoir JM, Lazar V, Dessen P, Roche S, Bertoglio J, Pierre J. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 modulates invasion and metastatic potential of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:942–55. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao R, Wang L, Wang H, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science. 2002;298:1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1076997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao Q, Yu J, Dhanasekaran SM, Kim JH, Mani RS, Tomlins SA, Mehra R, Laxman B, Cao X, Yu J, Kleer CG, Varambally S, et al. Repression of E-cadherin by the polycomb group protein EZH2 in cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:7274–84. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki T, Yoshida S, Hara H. Physiological concentrations of short-chain fatty acids immediately suppress colonic epithelial permeability. Br J Nutr. 2008;100:297–305. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508888733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tazoe H, Otomo Y, Kaji I, Tanaka R, Karaki SI, Kuwahara A. Roles of short-chain fatty acids receptors, GPR41 and GPR43 on colonic functions. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59(Suppl 2):251–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim CH, Park J, Kim M. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain Fatty acids, T cells, and inflammation. Immune Netw. 2014;14:277–88. doi: 10.4110/in.2014.14.6.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, Curi R. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients. 2011;3:858–76. doi: 10.3390/nu3100858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang Y, Chen Y, Jiang H, Robbins GT, Nie D. G-protein-coupled receptor for short-chain fatty acids suppresses colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:847–56. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sekhavat A, Sun JM, Davie JR. Competitive inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by trichostatin A and butyrate. Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;85:751–8. doi: 10.1139/o07-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davie JR. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by butyrate. The Journal of nutrition. 2003;133:2485S–93S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.7.2485S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iwanaga T, Takebe K, Kato I, Karaki S, Kuwahara A. Cellular expression of monocarboxylate transporters (MCT) in the digestive tract of the mouse, rat, and humans, with special reference to slc5a8. Biomed Res. 2006;27:243–54. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.27.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halestrap AP, Wilson MC. The monocarboxylate transporter family--role and regulation. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:109–19. doi: 10.1002/iub.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waldecker M, Kautenburger T, Daumann H, Busch C, Schrenk D. Inhibition of histone-deacetylase activity by short-chain fatty acids and some polyphenol metabolites formed in the colon. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry. 2008;19:587–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ang Z, Xiong D, Wu M, Ding JL. FFAR2-FFAR3 receptor heteromerization modulates short-chain fatty acid sensing. FASEB J. 2018;32:289–303. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700252RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park J, Kim M, Kang SG, Jannasch AH, Cooper B, Patterson J, Kim CH. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR-S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:80–93. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sivaprakasam S, Gurav A, Paschall AV, Coe GL, Chaudhary K, Cai Y, Kolhe R, Martin P, Browning D, Huang L, Shi H, Sifuentes H, et al. An essential role of Ffar2 (Gpr43) in dietary fibre-mediated promotion of healthy composition of gut microbiota and suppression of intestinal carcinogenesis. Oncogenesis. 2016;5:e238. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2016.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guillerey C, Huntington ND, Smyth MJ. Targeting natural killer cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1025–36. doi: 10.1038/ni.3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whiteside TL. Regulatory T cell subsets in human cancer: are they regulating for or against tumor progression? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63:67–72. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1490-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ang Z, Ding JL. GPR41 and GPR43 in obesity and inflammation – protective or causative? Front Immunol. 2016:7. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sina C, Gavrilova O, Förster M, Till A, Derer S, Hildebrand F, Raabe B, Chalaris A, Scheller J, Rehmann A, Franke A, Ott S, et al. G Protein-Coupled Receptor 43 Is Essential for Neutrophil Recruitment during Intestinal Inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;183:7514–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.