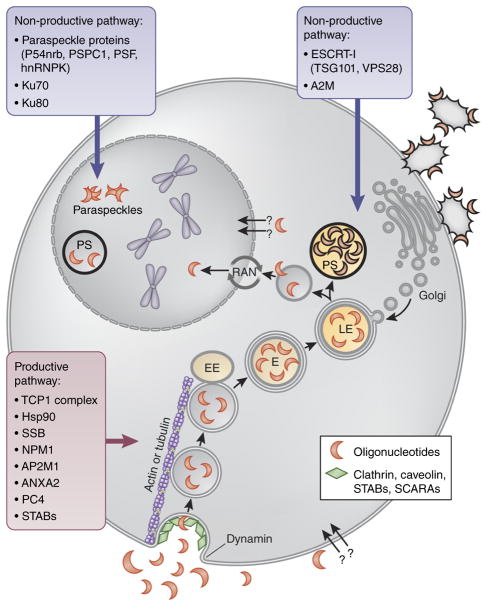

Figure 3.

Proposed oligonucleotide uptake mechanisms. It is proposed that ODNs enter cells by two competing pathways: productive pathway (gray outlines), which gives them access to their targets, and non-productive pathways (black outlines), which sequesters them in saturable sinks. Both productive and non-productive pathways start with ODNs being taken up by clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles. The endocytic vesicles bud from the plasma membrane, and GTPase dynamin catalyzes membrane scission. Freed cargo-containing vesicles are transported along actin- or tubulin-based cytoskeletal structures to fuse with early endosomes (EE). The fusion vesicles then undergo maturation. Internal pH of endosomes (E) drops to ~5.5 to accommodate the acid hydrolases involved in the degradation of the contents at the lysosome stage. Mature late endosomes (LE) eventually fuse with enzyme-containing transport vesicles, budded from the trans-Golgi network, to form lysosomes. This endosomal/lysosomal compartment likely corresponds to cytoplasmic phosphorothioate (PS)-bodies, large sharply defined structures intensely staining for ODNs. Productive and non-productive uptake pathways diverge during or after lysosome formation with the majority of oligonucleotides remaining in the non-productive pathway, possibly in endosomes/lysosomes, and a small amount escaping into the productive pathway, which likely involves ODN entry into the nucleus through the RAN-mediated pathway. Transfected ODNs may associate with paraspeckle proteins in the nucleus and form morphologically normal and apparently functional paraspeckle-like structures containing no NEAT1 RNA. Additionally, ODN can be sequestered into a non-productive pathway by binding to membrane-associated glycoproteins.