Abstract

Clinical studies have identified a correlation between type-2 diabetes mellitus and cognitive decrements en route to the onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Recent studies have established that post-translational modifications of the amyloid β (Aβ) peptide occur under hyperglycemic conditions; particularly, the process of glycation exacerbates its neurotoxicity and accelerates AD progression. In view of the assertion that macromolecular crowding has an altering effect on protein self-assembly, it is crucial to characterize the effects of hyperglycemic conditions via crowding on Aβ self-assembly. Toward this purpose, fully atomistic molecular dynamics simulations were performed to study the effects of glucose crowding on Aβ dimerization, which is the smallest known neurotoxic species. The dimers formed in the glucose-crowded environment were found to have weaker associations as compared to that of those formed in water. Binding free energy calculations show that the reduced binding strength of the dimers can be mainly attributed to the overall weakening of the dispersion interactions correlated with substantial loss of interpeptide contacts in the hydrophobic patches of the Aβ units. Analysis to discern the differential solvation pattern in the glucose-crowded and pure water systems revealed that glucose molecules cluster around the protein, at a distance of 5–7 Å, which traps the water molecules in close association with the protein surface. This preferential exclusion of glucose molecules and resulting hydration of the Aβ peptides has a screening effect on the hydrophobic interactions, which in turn diminishes the binding strength of the resulting dimers. Our results imply that physical effects attributed to crowded hyperglycemic environments are incapable of solely promoting Aβ self-assembly, indicating that further mechanistic studies are required to provide insights into the self-assembly of post-translationally modified Aβ peptides, known to possess aggravated toxicity, under these conditions.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of senile dementia and currently affects nearly 45 million people worldwide. It is a progressive, multifactorial, and irreversible disorder characterized by various pathological markers in the brain, particularly fibrillar deposits of the 4 kDa amyloid β (Aβ) peptide in the neuronal synapses.1−3 Aβ is an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) and hence defies the long-standing protein structure–function paradigm.4−7 The lack of a single, well-defined equilibrium structure usually makes IDPs highly prone to self-assembly and aggregation, and in several cases such as Aβ, the insoluble aggregates are associated with the onset of debilitating neurodegenerative and other diseases.8−10 The amyloid hypothesis postulates that the aggregation of Aβ into insoluble, fibrillar aggregates marks the onset of AD.11 However, in recent years, accumulating evidence substantiates the hypothesis that small, soluble Aβ oligomers, rather than mature fibrils formed subsequently, may be the critical players in the pathology of AD.12−16 Hence, uncovering the mechanisms of early self-assembly and oligomeric interactions, as well as factors that can potentially accelerate or slow down the rate of self-assembly of Aβ are among the key prerequisites for developing effective therapies against AD onset and progression.

Over the last few decades, increasing clinical evidence has shown a correlation of AD onset and cognitive decline with the occurrence of hyperglycemia and type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in elderly individuals.17−21 It has been observed that elevated blood glucose levels caused by several factors including insulin dysfunction and resistance may increase the chances of AD pathogenesis.21,22 However, conclusive evidence demonstrating mechanistic linkages between excess glucose in the bloodstream and the onset of AD is still lacking. The search for the underlying causative factors is further complicated due to seemingly contradictory evidence. For example, it has been suggested that glucose may have some beneficial effects on the cognitive abilities of healthy individuals, whereas hyperglycemia may trigger neuronal death by excessive amyloid deposition in those already predisposed toward AD.23 An emerging consensus appears to associate the post-translational chemical modifications of Aβ in hyperglycemic environments to its rate of self-assembly.23,24 Particularly, Aβ modified as an advanced glycation end product (AGE) is thought to possess aggravated toxicity compared to that of the unmodified Aβ.25,26 Using extensive atomistic computer simulations, we have recently demonstrated that Aβ with AGE modified lysines possesses greater β-sheet propensity and is thermodynamically predisposed to stronger self-association.27

It is noteworthy here that although AGE modifications of Aβ are found to enhance the peptide’s self-assembly, there exist no studies to date on how hyperglycemic conditions may directly influence the protein’s self-assembly thermodynamics and thereby modulate the process in an alternative manner independent of plausible chemical modifications. This aspect becomes particularly important when one notes that macromolecular crowding of the aqueous environment can play a major role in altering the physical characteristics of a protein and its rate of self-association.28−34 Particularly, simple sugars such as glucose, trehalose, sucrose, and polysaccharides such as dextran and Ficoll, frequently used as molecular crowding agents and as components for mimicking cytoplasmic crowding environments, can have profound effects on protein self-assembly.35−39 Various experimental and theoretical studies have demonstrated modest to drastic effects of macromolecular crowding on protein self-assembly and aggregation.29,40−47 It is further interesting to note recent works demonstrating that mixtures of solvents may influence protein conformation and solubilities in a manner distinct from those brought about by pure solvents.48,49

In light of the crucial influence of glucose in the aggregation propensities of Aβ, and thereby in the onset of AD, it is imperative to decouple its potential physical effects vis-à-vis crowding and its possible roles via chemical modifications in the modulation of Aβ self-assembly. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been widely used to provide molecular insights into the structure, dynamics, and self-assembly of amyloidogenic proteins such as Aβ, islet amyloid polypeptide, α-synuclein, and prion.50−69 Herein, we present a systematic study based on fully atomistic computer simulations of the role of glucose molecules in modulating the dimerization of independent, full-length Aβ units. This earliest step in Aβ self-assembly is a crucial component in the nucleation–polymerization growth of Aβ oligomers, protofibrils, and fibrils.50,70 Our studies reveal that high glucose concentrations have a small effect on the overall properties of the Aβ monomer including conformational fluctuations, structure compactness, intrapeptide contacts, and secondary structure propensities. Upon analyzing the early dimerization of Aβ peptides in glucose solution, we observed that there is a small but appreciable weakening in the binding strength of the dimers, concurrent with an observable loss in contacts between the hydrophobic domains of the peptide units. A component-wise analysis of the binding free energy reveals that the loss arises primarily from the weakening of the van der Waals (vdW) interaction energies accompanying the loss in residue contacts. Considering the potential crowding effects brought about by glucose molecules, we further investigated the solvent distributions in the vicinity of the Aβ dimeric complexes and found important effects that arise due to the presence of glucose. Our calculated preferential interaction parameters indicate that glucose molecules form a “cage” within about 5–7 Å of the protein heavy atoms that trap water molecules in the vicinity of the protein and create a distinctive increase in side chain hydration. This excess hydration reduces the efficacy of the hydrophobic effect and weakens the interactions between the hydrophobic domains of the Aβ units, accounting for an approximately 50% reduction in the strength of the binding free energy. Our results offer strong credence to the hypothesis that “standalone” physical effects of hyperglycemic conditions are incapable of consolidating Aβ self-assembly and enhancing its aggregation. Therefore, the observed clinical effects of hyperglycemic conditions on AD should be primarily via chemical modifications of Aβ, and plausibly through AGE modifications.

Results and Discussion

Effects on Monomeric Conformation

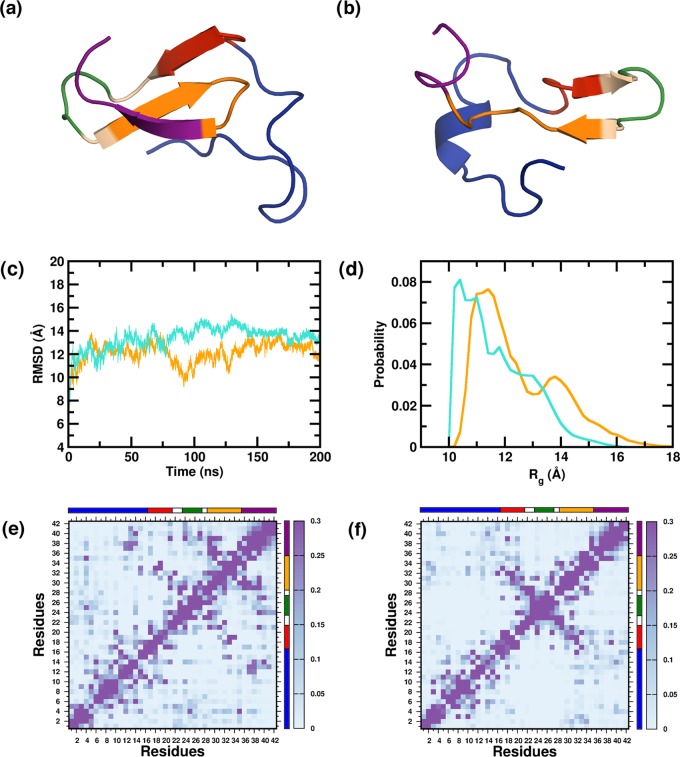

We begin first by investigating the effect of glucose molecules on the conformational dynamics of the Aβ monomeric conformation. Representative snapshots from the PW-M and PG-M ensembles are illustrated in Figure 1a,b. In Figure 1c, we present the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the monomer relative to the initial structure in the PW-M and PG-M systems, averaged over multiple simulation trajectories. We find that amongst the two systems, the average RMSD of the monomer is only slightly lower in glucose solution than that in pure water (PW), indicating a very marginal difference in fluctuations of the monomer in the presence of glucose. The mean RMSD values for the PG-M and PW-M systems, averaged over the last 150 ns, are 12.2 (±0.8) and 13.7 (±0.6) Å, respectively.

Figure 1.

Representative structure from the monomeric ensembles (a) PW-M and (b) PG-M. The peptides are colored segment-wise. (N-terminal region (NTR)—blue, central hydrophobic core (CHC)—red, turn region (TR)—green, second hydrophobic region (SHR)—orange, C-terminal region (CTR)—magenta.) (c) Time evolution of the backbone RMS deviations from the starting structure, averaged over multiple trajectories. (d) Distributions of the radius of gyration (Rg) of the PW-M and PG-M ensembles. Data for the PW-M and PG-M systems are shown in turquoise and orange, respectively. Intramonomer residue–residue contact probabilities for the (e) PW-M and (f) PG-M systems. Axes denote the residue numbers. The color scale for the contact probability is shown at the extreme right of each plot. The color bar at the top and right of each plot represents the segments in the Aβ peptide.

Several studies have reported that in water, Aβ peptide adopts collapsed conformations that are attributable largely to the strong hydrophobic interactions of the CHC, and the hydrophobic regions at the C-terminus of the peptide.71−78 We analyzed the radius of gyration of the monomer of the two systems as a measure of the peptide’s overall compactness. The mean Rg value of the Aβ monomer is 12.9 (±0.8) in the PG-M system and 11.5 (±0.5) Å in the PW-M system over the last 150 ns of the trajectories, indicating a small decrease of the mean Rg by 1.4 Å in the latter system. In Figure 1d, we compare the distribution of Rg values, and an overall shift to slightly higher values accompanied by a slight narrowing of the distribution is evident in the PG-M system. We note here that the probability distribution of Rg of the PW-M system peaks at 10.4 Å, which is in close agreement with a previous report.53 The peak positions in the Rg distribution in PG-M can be observed at 11.4 and 13.8 Å, further underscoring the changes in compactness in the presence of glucose within the solvent environment.

As reported extensively in previous studies,27,52 the collapse of the Aβ peptide in an aqueous environment arises due to dewetting transitions and the resulting favorable interactions between distal hydrophobic residues located within the peptide sequence. To understand the key inter-residue interactions that are altered in the presence of glucose, we compared the intramonomer contact maps, which are presented in Figure 1e,f, respectively. For our analyses, we considered five segments of the Aβ peptide: NTR (D1AEFRHDSGYEVHHQK16), CHC (L17VFFA21), TR (V24GSN27), SHR (G29AIIGLM35), and CTR (V36GGVVIA42). The NTR and TR segments are mostly hydrophilic, whereas the CHC, SHR, and CTR segments are mainly hydrophobic. The contacts obtained in PW-M are similar to those reported in previous studies. The strongest inter-residue contacts are observed in the CHC/SHR, TR/CTR, and SHR/CTR regions. Importantly, a large number of the strongest contacts observed in PW-M are lost in the PG-M system; upon inspection, it was revealed that the contacts lost in PG-M are predominantly hydrophobic contacts. The number of high probability, non-nearest neighbor contacts, defined as contacts between residues spaced by three or more units in the sequence, is 41 in the PW-M system and 28 in the PG-M system. Interestingly, we find that in addition to the loss in key hydrophobic contacts, a few strong contacts involving nonhydrophobic residues emerge in the PG-M system, suggesting a subtle alteration in the role of the solvent environment in contact formation upon the addition of glucose. This aspect is further corroborated when we compare the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of the high probability contact residues in both systems. The SASA per contact residue side chain is 69.2 Å2 in PW-M and 81.0 Å2 in PG-M, indicating that the contacts formed are relatively more exposed to the solvent in the latter system.

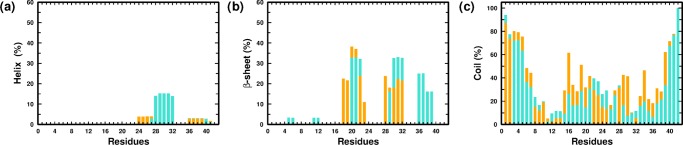

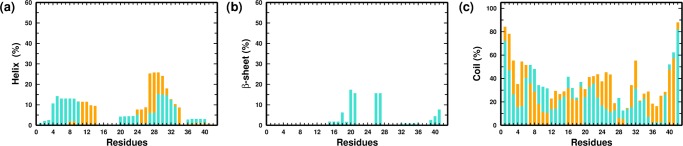

We finally examined the residue-wise secondary structural propensities of the monomers in the two systems; the comparisons are depicted in Figure 2a–c. In PW-M, the β-strands are mainly located in the NTR, CHC, SHR, and CTR regions; it is noteworthy that these regions participate maximally in the intramonomer contacts and in the overall compactification of the peptide monomer in water. We point out that similar conformational contacts in these regions have been reported previously in experimental and computational studies.51,75,78−81 The comparison between the PW-M and PG-M systems indicates that the presence of glucose is correlated with an overall decrease in β-strand propensities within the monomer.

Figure 2.

Residue-wise percentage secondary structure content of the (a) helix, (b) β-sheet, and (c) coil for the PW-M (in turquoise) and PG-M (in orange) ensembles.

These preliminary analyses indicate that the presence of glucose in the aqueous environment triggers small changes in the peptide’s conformational fluctuations, compactness, intrapeptide hydrophobic contacts, solvent accessibility, and in the overall secondary structural propensities. In the following sections, we investigate in detail the ramifications of these changes on the peptide’s self-association into the dimeric structure, and the associated differential role of solvation attributed to the presence of glucose.

Intermonomer Association and Structural Propensities

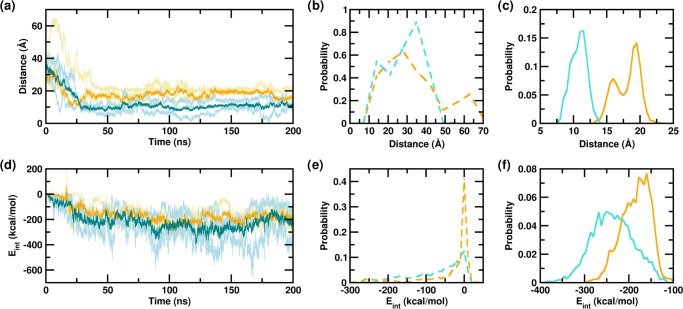

It is well-known that the Aβ peptide can self-associate to form several different assembly forms ranging from dimers to higher oligomers and aggregates of amyloid fibrils.13,16,78,82,83 The Aβ dimer is of particular interest as it is the smallest neurotoxic species that impairs synaptic plasticity and memory, and further it is a key component in the nucleation mechanism.82,84−87 Experimental and computational studies showed that Aβ1–42 forms stable dimers in solution.88−90 Herein, we have characterized the physical effect of glucose crowding on the spontaneous Aβ dimeric assembly process from the initial monomeric state. The dimerization event was first monitored via the center of mass distance between the two monomers in PW and in the glucose solution. Figure 3a shows the time evolution of the center of mass distance between the two monomeric units. The distributions of the distances obtained from the first 25 ns, as well as from the last 150 ns of the independent trajectories of the PW-D and PG-D systems are compared in Figure 3b,c. We observe that within the first 25 ns, the intermonomer distance in the PW-D system decreases dramatically from 33 to 10 Å. A similar phenomenon is observed in the PG-D system in which the intermonomer peptide distance, on average, decreases to 11 Å within the initial 25 ns. The mean intermonomer center of mass distances in the PW-D and PG-D systems are similar within the first 25 ns of simulations, being 21.5 (±7.1) and 25.3 (±5.5) Å, respectively. In the PW-D system, after the initial 25 ns, the intermonomer distance fluctuates around 10–11 Å for the remaining part of the trajectory. However, in the PG-D system, beyond 25 ns, the distance increases to about 20 Å in the next 10 ns and then fluctuates between 18 and 20 Å subsequently. Within the last 15 ns, the interpeptide center of mass distance in this system again decreases to 16 Å. This is reflected in the bimodal distance distribution in the PG-D system, with a smaller population peaking at 16 Å and a relatively larger population peaking at around 18–20 Å. The mean intermonomer center of mass distances in the PW-D and PG-D systems over the last 150 ns are 10.5 (±1.2) and 17.8 (±1.9) Å, respectively. It is worth noting here that although both systems exhibit a drop in the interpeptide distance within the first 25 ns and a relative stability in this value over the last 150 ns, at any point of time, the mean distance is always greater in the PG-D system, suggestive of a discernable effect of glucose crowding on the spontaneous dimerization ability of Aβ in water.

Figure 3.

Evolution of the (a) interpeptide center of mass distance and (d) interpeptide interaction strength over the simulation timescale. Data for the PW-D and PG-D trajectories are shown in light blue and gold, respectively, and the averages corresponding to them are shown in teal and orange, respectively. (b and e) Probability distributions for the first 25 ns and (c and f) last 150 ns, corresponding to the data in (a) and (d). PW-D and PG-D are shown in turquoise and orange, respectively.

We further evaluated the intermonomer interaction energies as a function of simulation time in the PW-D and PG-D systems; this quantity has previously been used as an (preliminary) indicator of the interpeptide interactions (binding strengths).27,81,88,91,92Figure 3d depicts the time evolution of the interactions as observed in the trajectories of the PW-D and PG-D systems. Spontaneous dimerization of the Aβ peptide in both systems is marked by a lowering of the interaction energies within the first 50 ns, followed by a stability in the interaction energies over the latter part of the trajectories. Figure 3e,f depicts the probability distributions of the interpeptide interactions over the first 25 ns and the last 150 ns. The distribution over the first 25 ns peaks at 0.0 kcal mol–1 in both the PW-D and PG-D systems, indicating a lack of any significant initiation of dimerizing interactions in the earliest part of the trajectories. We mention here that the lack of significant interactions in the earliest parts of the simulations, noted previously in other reports, corresponds to the diffusive part of the Aβ dimerization process.88,93 Unlike the early distributions, the distributions over the latter parts of the trajectory peak at −268.0 and −160.0 kcal mol–1, respectively, in the PW-D and PG-D systems, indicating the presence of strong interpeptide dimerizing interactions. It is noteworthy that although the peaks corresponding to the two systems are well separated, there is a distinct degree of overlap between the two distributions. However, the distribution for the PG-D system is markedly narrower than that of the PW-D system, indicating a lower extent of fluctuations in the interactions in the presence of glucose in the solvent environment. The mean and standard deviation values of the interaction energies over the final 25 ns of the PG-D and PW-D simulation trajectories are −175.0 (±23.7) and −192.2 (±29.8) kcal mol–1, respectively.

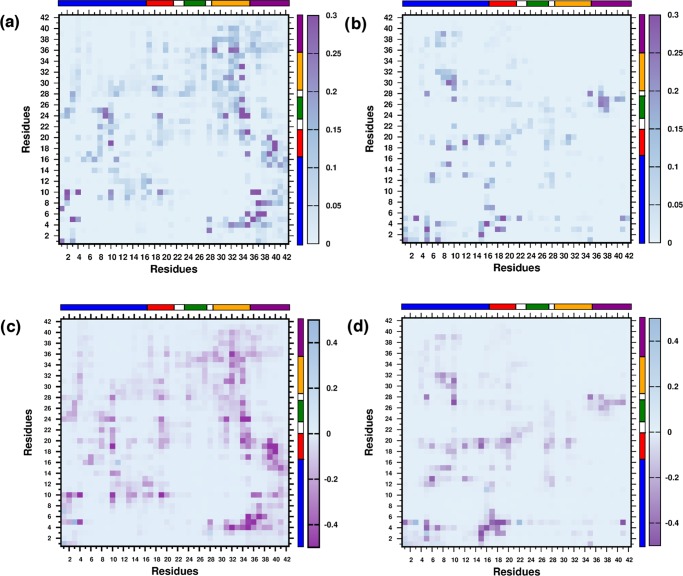

We next proceeded to analyze the structural features of the dimers formed in the two systems by comparing the intermonomer residue–residue contact probability map, illustrated in Figure 4a,b, respectively. We computed the contact probability for the last 150 ns of each trajectory, leading to a cumulative simulation time of 450 ns for each system. As in other recent studies, a pair of residues forms a contact if the center of mass distance between their side chains does not exceed 7 Å.27,75,81,92 As apparent from the comparison of contact maps, there is a significant reduction in the total number of intermonomer contacts in PG-D as compared to that of the PW-D system. We note that in the PW-D ensemble, the region of high contact density involves hydrophobic interactions between the CHC and CTR segments, which is in agreement with the previously reported studies.27,94 The SHR/CHC, SHR/TR, SHR/SHR, and SHR/CTR regions also display high contact density. Interestingly, there is a high density of contacts between the hydrophilic NTR and hydrophobic CTR regions. In addition, a moderate density of contacts is localized in the NTR/CHC and NTR/TR regions. On the other hand, in the PG-D system, a reduction in the intermonomer contacts is evident amongst the hydrophobic segments CHC, SHR, and CTR, whereas there is a modest density of contacts between the hydrophilic NTR with NTR as well as the hydrophobic CHC and SHR segments. Contacts are also formed between the hydrophilic TR and hydrophobic CTR region. We have further provided the intermonomer interaction energy maps corresponding to the average vdW interaction among the residues in Figure 4c,d for the PW-D and PG-D systems, respectively. We observe that the inter-residue contact probabilities among the monomers are vividly reflected in the average vdW interaction energies. Especially noticeable is the substantial weakening of vdW interaction energies in the hydrophobic patches of the peptides in the PG-D system, which corroborates with a loss of contacts in these regions. We further analyzed the secondary structural propensities of the Aβ peptides of the dimeric systems in the two solvent environments. Comparing the overall secondary structure content in the two systems, depicted in Figure 5a–c, we observe a subtle β-sheet propensity of the residues in the hydrophobic CHC, TR, and CTR segments in PW-D. It is interesting to note that β-sheet propensity in these regions is absent in the PG-D system. The discussion above demonstrates that the spontaneous dimerization of Aβ peptide is discernably compromised in the presence of glucose molecules. Importantly, the dimerization process is primarily affected by the distinct loss in key hydrophobic contacts that are known to play important roles in Aβ assembly.

Figure 4.

Interpeptide residue-wise contact probability maps for the (a) PW-D and (b) PG-D systems. Interpeptide residue-wise average vdW interaction energies (in kcal mol–1) for the (c) PW-D and (d) PG-D ensembles.

Figure 5.

Residue-wise percentage secondary structure content of the (a) helix, (b) β-sheet, and (c) coil for the PW-D (in turquoise) and PG-D (in orange) ensembles.

Thermodynamics of Aβ Binding

The analyses presented thus far demonstrate that hyperglycemic conditions within the aqueous environment of the full-length Aβ peptide alter its conformational fluctuations, secondary structure, compactness, solvent exposure, and propensity for self-association in a noticeable manner. For deeper insights into the origins of the distinct weakening of Aβ dimerization observed in the presence of glucose, we calculated and compared the intermonomer binding free energy of the peptide units, along with the individual contributing components. This was done with the molecular mechanics-generalized born surface area (MM-GBSA) protocol as described in the Methods section. We point out that this method has been routinely used to obtain binding affinities of biomolecules.95−97 The mean and standard deviations of the various contributions to the total binding free energy are presented in Table 1. From these data sets, it can be observed that the mean value of the binding free energy, ΔGbind, is lower in the PW-D system than that in the PG-D system by a value ranging from 25.2 to 27.2 kcal mol–1, reflecting the relatively stronger dimerizing interactions in the former system. It is observed in both systems that the favorable binding free energy of dimerization originates predominantly from the nonpolar terms, namely, ΔEvdW and ΔGsolv-np. Interestingly, the fluctuations observed in each component of the binding free energy are consistently higher in the PW-D system. The contribution of the electrostatic interactions between the two monomers (ΔEelec) is offset by the contribution arising due to the polar solvation free energy (ΔGsolv-pol). It is important to note here that a critical component of the binding ΔGbind is obtained from the solvation free energy of the nonpolar moieties of the dimerizing units, ΔGsolv-np; this quantity is markedly lower in the PW-D system. This observation suggests a relatively greater thermodynamic favorability of sequestering hydrophobic contacts in the PW-D system; this is corroborated by results discussed later. The magnitude of the differences in ΔGsolv-np between the two systems varies between 6.6 and 7.5 kcal mol–1. Overall, these results suggest that in the crowded environment of glucose solution, there is a distinct weakening of the binding free energies that contributes to the dimerization of the full-length Aβ units. Such behavior qualitatively agrees with experimental and computational findings that sugars, which function as osmolytes within cells, hamper the aggregation of amyloidogenic peptides or globular proteins.36,98−101 We point out that previous reports of Aβ dimerization have ignored the contributions arising due to loss in configurational entropy.93,102 We estimated the cumulative configurational entropy of the protein backbone atoms of the Aβ peptides for the PW-D and PG-D systems, calculated for the initial 10 ns of the dimerizing trajectories when the proteins exist as individual units as well as for the last 10 ns when the proteins have dimerized, using Schlitter’s method,103 as described in the Supporting Information (SI). The entropy change of the Aβ peptides upon dimerization (ΔSmonomer–dimer) is small and comparable for the PW-D and PG-D systems, the values being 1.1 × 10–3 and 0.9 × 10–3 kcal mol–1 K–1, respectively. Therefore, they are not considered in the calculation of ΔGbind. The results presented thus far establish that the self-association of full-length Aβ units is thermodynamically weakened when an excess of glucose molecules is present.

Table 1. Individual Contributions of the Interpeptide Binding Free Energies Calculated for the Last 150 ns of Each Trajectory in the PW-D and PG-D Systems (in kcal mol–1)a.

| contribution | PW-D | PG-D |

|---|---|---|

| ΔGbind | –54.739 (±18.685) | –27.584 (±11.847) |

| ΔHMM | –241.996 (±105.642) | –185.145 (±68.752) |

| ΔEelec | –169.391 (±95.823) | –150.682 (±71.374) |

| ΔEvdW | –72.605 (±18.753) | –34.463 (±19.895) |

| ΔGsolv | 187.257 (±90.258) | 157.561 (±61.259) |

| ΔGsolv-np | –15.660 (±3.712) | –8.202 (±3.090) |

| ΔGsolv-pol | 202.917 (±93.074) | 165.763 (±61.767) |

See the text for details. Standard deviations are provided in brackets.

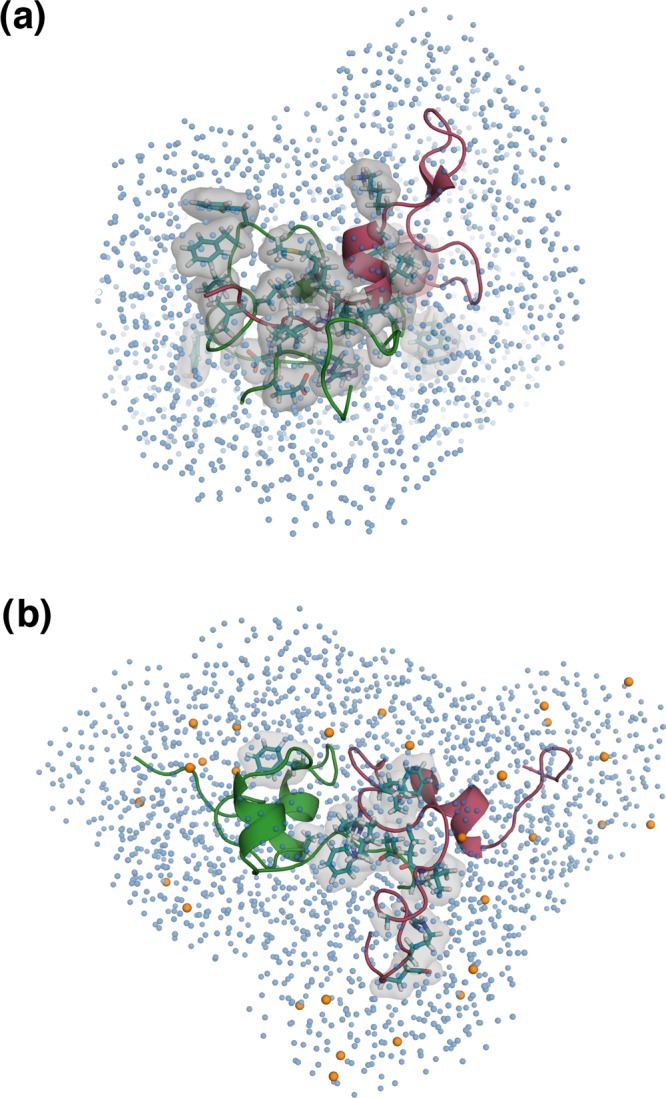

Glucose Caging Modulates Aβ Hydration and Interactions

The solvent environment has a profound influence on the self-assembly behavior of IDPs such as Aβ.52,93,104−108 Importantly, dewetting transitions and hydrophobic associations between Aβ monomers play a crucial role in the peptide’s self-association.52,76,77 In Figure 6, we depict representative snapshots of the dimeric state of the protein in the absence and in the presence of glucose in the solvent environment. The weakened association between the Aβ units and the resultant loss in the compactification of the dimeric state in the presence of glucose in the solvent is evident upon comparison.

Figure 6.

Representative structures from the dimeric ensembles (a) PW-D and (b) PG-D; the two peptide units are colored in pink and green. The residues involved in interpeptide high probability contacts are depicted by a translucent gray surface, with side chains represented as sticks and colored teal. Glucose molecules around the PG-D dimer within a distance of 7 Å from the protein units are shown as orange colored spheres and the water oxygens around the dimers in both the systems are shown as spheres colored skyblue.

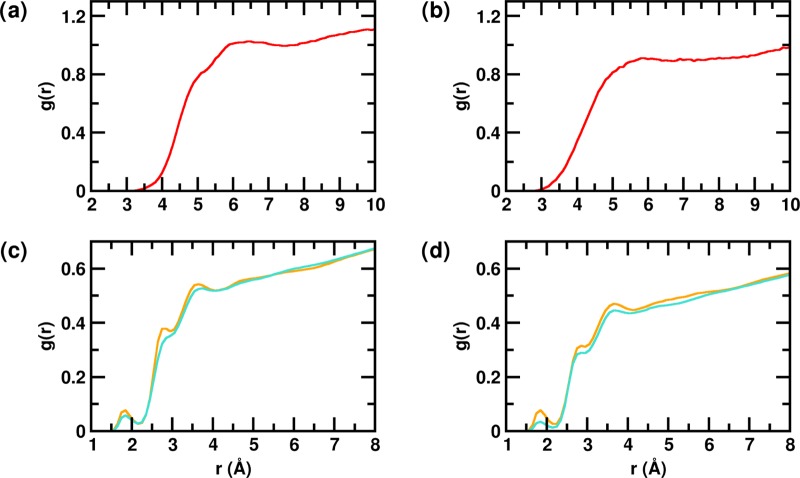

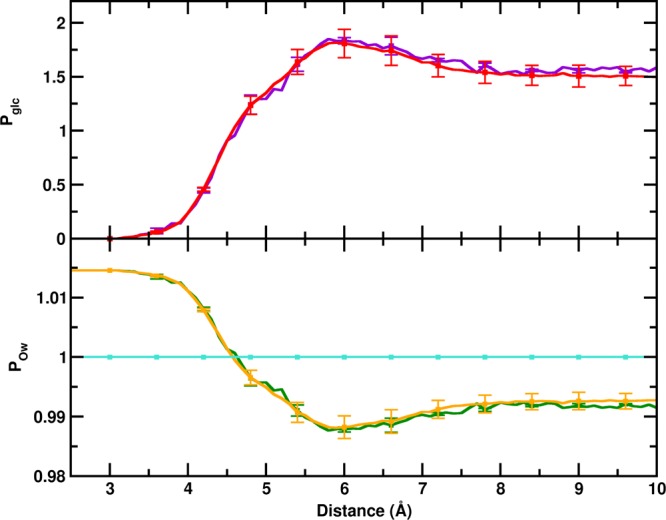

In light of our findings, we further investigated how the nature of surface hydration could be altered in the presence of glucose. We first computed the selected site–site radial distribution function, g(r), involving the protein and the different solution species in PW and glucose solution, for both the monomeric and dimeric systems. The g(r) between the protein heavy atoms and center of mass of glucose molecules in the PG-M and PG-D systems is shown in Figure 7a,b, respectively. We note that the protein–glucose g(r) begins to gradually increase from 3.5 Å and forms a broad peak centered at 6 Å. This indicates that there is a high density of glucose molecules in the shell between 5 and 7 Å around the protein. Figure SI-1a,b displays the g(r) calculated between the protein heavy atoms and water oxygen atoms in the monomeric (PG-M and PW-M) and dimeric (PG-D and PW-D) systems, respectively. Interestingly, we observe that in the first and second peaks of the protein–water g(r), positioned at 2.8 and 3.8 Å, respectively, there is a marginal but noticeable enhancement in the hydration (see the figure inset) in the glucose system over that in PW; this enhancement is consistently observed in both the monomeric and dimeric systems. For insights into the origin of this marginal difference, we calculated the radial distribution functions between the water oxygens and the full side chains of the residues that participate in internal contacts (monomeric systems), and in the interpeptide contacts (dimeric systems) with high probability. This comparison, presented in Figure 7c,d for the monomeric and dimeric systems, respectively, clearly shows marked enhancements in the first and second solvation peaks in the presence of glucose. This indicates that the differences observed earlier can be largely attributed to the enhanced hydration of the internal contacts formed within the monomer in the PG-M compared to that in the PW-M system, and to the interpeptide contacts formed within the dimer in the PG-D compared to that in the PW-D system. In Table SI-1, we have tabulated the number of high probability, nonlocal internal contacts (in monomer) and interpeptide (in dimer) contacts observed in the absence and in the presence of glucose. It is noted that although some of the contacts are common, there is an overall decrease in the number of hydrophobic contacts in the presence of glucose. Interestingly, in the dimeric PG-D system, most of the nonlocal contacts formed involve the participation of polar residues (see Table SI-2), reflecting the relatively greater difference in g(r) observed in Figure 7d. We further note here that the average SASA of the side chains that contributes to the nonlocal interpeptide contacts increases about 3-fold in the PG-D system in comparison to that in the PW-D system (see Table SI-3). Furthermore, we evaluated the mean tetrahedral order parameter (Q) of the water molecules that lie within 5 Å of the interpeptide contact residues in the dimeric systems (see Table SI-3). The tetrahedral order parameter is an indicator of the structural ordering of the local hydration waters.109−111 A marginal decrease in the average Q of the waters in the vicinity of the contacts in the PG-D relative to that in the PW-D system reflects a small decrease in the overall local ordering of hydration waters around the contact residues.

Figure 7.

Site–site radial distribution function, g(r), between protein heavy atoms and glucose center of mass of the (a) PG-M and (b) PG-D systems is represented in red. The g(r) between the water oxygen atoms and full side chains of residues involved in high probability contacts of the (c) monomeric (PW-M and PG-M) and (d) dimeric (PW-D and PG-D) systems. Data corresponding to the PW and glucose solution (PG) are shown in turquoise and orange, respectively.

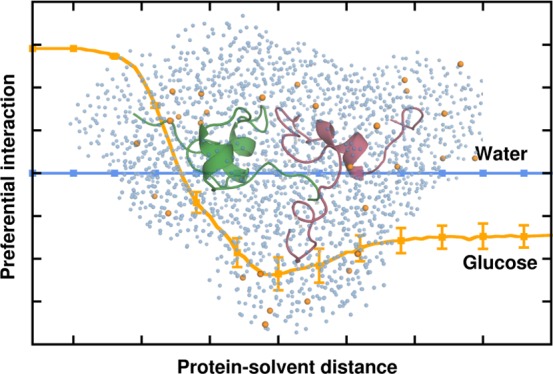

To further ascertain the preferential hydration of Aβ peptides in glucose solution, we characterized the relative local distribution of water and glucose molecules around the Aβ dimers, as described in the Methods section. Figure 8 depicts the normalized fraction of glucose molecules (Pglc) and water oxygen (POw), as a function of the distance from the protein heavy atoms in PW and glucose solution. Commensurate with the g(r) trends, it can be observed that up to a distance of 4.5 Å from the protein heavy atoms, POw is greater than 1, which signifies that the Aβ peptides are more preferentially hydrated in the glucose solution. In addition, Pglc is lower than 1 at a distance below 4.5 Å with a peak greater than 1 in the distance range 5–7 Å. This indicates that the glucose molecules are excluded from the surface of the dimer and form a dense space-filling network surrounding the dimer at a distance of 5–7 Å, which causes a depletion of water in this region. This cage-like network traps the water molecules at the surface of the protein resulting in enhanced hydration of the dimer. Considering the relevance of a dewetting-induced hydrophobic collapse to Aβ self-assembly, we further investigated if the phenomenon of glucose caging and enhanced protein surface hydration occurs at the dimer interface. Analyses of the preferential interaction parameters for the dimer interface region, depicted in Figure 8, reveal that concurrent to the whole dimer, the interfacial region is characterized by a water-enriched hydration shell resulting from the caging effect of glucose. We remark here that the presence of the water molecules caged at the protein surface by the glucose clusters reduces the overall interactions between hydrophobic residues that provide a major driving force for Aβ self-assembly, and account for the reduced binding strength of the resulting dimers.

Figure 8.

Time-averaged normalized preferential interaction parameters of the relative local distribution of glucose (Pglc) and water (POw) in the dimeric trajectories. The upper panel shows Pglc for the PG-D dimer (in red) and the dimer interface (in violet) and the lower panel represents POw for PW-D and PG-D (whole dimer), in turquoise and orange, respectively, the ratio for the PG-D dimer interface is shown in green.

Conclusions

Numerous epidemiological studies over the last few decades have linked T2DM to an increased risk of AD.17−21 Notably, evidence has suggested that hyperglycemia-mediated glycated Aβ (Aβ-AGE) is significantly more pathogenic than the unglycated one and augments AD progression both in vitro and in vivo.25,26 However, with accumulating knowledge on the implications of macromolecular crowding on protein self-assembly, there are currently no studies probing the physical aspects of crowded hyperglycemic conditions on the thermodynamics of Aβ self-assembly. Further, it is important to note complex effects that may be brought about on biomolecular conformations by the crowding interactions of solvent mixtures.48,49 In light of such observations, we have, in the present study, used classical MD simulations to delineate the physical effects of the crowded environment of aqueous glucose solution on the conformational stability and the self-assembly characteristics of full-length Aβ peptide. We find that the glucose-crowded environment has a narrow but discernable impact on the Aβ monomer with respect to its conformational fluctuations, compactness, internal contacts, solvent exposure, and in its overall secondary structure propensities. Our simulations of the early self-assembly of Aβ monomers reveal that the resultant dimers in glucose solution exhibit weakened peptide–peptide binding free energies and a substantial loss in the number of intermonomer contacts. It is noteworthy that the reduced binding strength of the dimers mainly arises from overall weakening of the dispersion interactions that is commensurate with the loss of inter-residue contacts in the hydrophobic segments of the peptides. Considering the critical role that hydration water plays in protein aggregation as well as the excluded volume effect owing to the presence of glucose molecules, we evaluated the local hydration pattern of the dimers to elucidate if crowding modulates Aβ hydration. Our analysis of the preferential interactions of Aβ with the solvent species indicates that glucose molecules cluster around the peptides at a distance of 5–7 Å and enrich the shell in the vicinity of the protein surface with water molecules. This preferential hydration of the Aβ peptides and the caging effect of glucose molecules screen the hydrophobic interactions between the peptides and weaken the binding strength of the resulting dimers. Our results demonstrate the physical effects of hyperglycemic conditions and the resultant crowding effects on the conformational properties and early self-assembly of Aβ.

Further studies in our laboratory are underway to dissect the effects of crowding on the microscopic details of the structural and dynamical properties of the hydration layer of the Aβ dimers in glucose solution. In view of the enhanced Aβ neurotoxicity upon hyperglycemia induced chemical modifications, it is further important to gain a molecular level understanding of the self-assembly of these chemically modified Aβ peptides under hyperglycemic conditions. These studies will aid in gaining molecular insights into the copathogenesis of T2DM and AD as well as provide incentives to design effective therapeutic strategies to counteract the harmful effects of these debilitating diseases.

Methods

System Setup and MD Simulations

All MD simulations reported in this study were performed using the NAMD simulation package.112 The details of the Aβ conformations generated and used are described below. The simulations were performed under periodic boundary conditions using the NAMD2.9 simulation package.112 The CHARMM22 force field with CMAP correction113 was used to simulate the peptides, the CHARMM36 all-atom carbohydrate force field113 was used for glucose parameters, and the TIP3P114 water model was used for the solvent. We point out that the CHARMM force field has been noted to sample Aβ conformations with high levels of accuracy.115 A time step of 2 fs was used. A constant temperature of 310 K was maintained with Langevin dynamics at a collision frequency of 1 ps–1, and a pressure of 1 atm was maintained with the Nosé–Hoover method.116 Long-range electrostatic interactions were computed using the particle-mesh Ewald method117 and covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms were constrained using the SHAKE algorithm.118 The systems were first energy minimized for 15 000 steps using the conjugate gradient method followed by simulations in the isothermal–isobaric (NPT) ensemble. Three independent MD simulations were performed for full-length Aβ units in PW and glucose–water mixture (PG) solvents. Each trajectory was of 200 ns duration, amounting to a cumulative simulation time of 0.6 μs for each system.

Aβ Simulations

The details of the generation of the Aβ monomeric conformation can be found in previous work conducted by our group.27,81 Briefly, the solution state NMR structure of the full-length Aβ1–42 peptide obtained in a 3:7 mixture of hexafluoro-2-propanol and water (PDB entry: 1Z0Q)119 was heated in the gas phase at 373 K. From the ensemble of the random coil configurations, ten structures were independently simulated at 310 K in explicit water for a minimum of 150 ns, generating a cumulative simulation data set of over 1.6 μs. Principal Component Analysis was then performed on the ensemble of the Aβ conformations and a conformation of the peptide representing one of the most populated clusters was chosen as the starting monomeric structure for our studies. The representative structure was benchmarked with experimental data by simulating it for 6 ns and comparing the 15N and 13Cα chemical shifts, which were calculated using the SHIFTS program.120 We point out here that the structural propensities of the chosen initial conformation are remarkably similar to those of the full-length Aβ conformation reported to populate the peptide’s ensemble in water.51,53

The dimeric simulations were initiated by placing the two Aβ monomers at a center of mass distance of 33 Å and solvating in PW and glucose solution to obtain the PW-D and PG-D systems, respectively. The PW-D system was solvated explicitly in a cubic box containing 22 284 TIP3P114 water molecules. The glucose simulation box of the PG-D system was built by placing the two monomeric structures at a center of mass distance of 33 Å with a random distribution of glucose molecules using the Packmol121 program, followed by solvation with TIP3P114 water molecules. The glucose concentration chosen was 108 g L–1, which amounted to 218 glucose molecules in a cubic box containing 14 968 water molecules. The minimum distance from the extremities of the protein to the edge of the simulation box was at least 15 Å. Similarly, for the monomeric systems, the Aβ peptide conformer described above was solvated in a cubic box of water and glucose solution at a concentration of 108 g L–1 to obtain the PW-M and PG-M systems, respectively. For each protein–solvent system, three independent trajectories of 200 ns each were generated. The system and simulation details are summarized in Table 2. All of the trajectories were equilibrated for 50 ns, and the nontemporal analyses were done for the equilibrated part (last 150 ns) of the trajectories.

Table 2. Details of the Simulated Aβ Systemsa.

| type | name | solvent | d0 | SW | SG | box dimensions (Å3) | Ttotal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| monomer | PW-M | water | 12 905 | 74 × 79 × 69 | 0.6 | ||

| monomer | PG-M | water–glucose | 9136 | 135 | 71 × 76 × 67 | 0.6 | |

| dimer | PW-D | water | 33 | 22 284 | 107 × 91 × 71 | 0.6 | |

| dimer | PG-D | water–glucose | 33 | 14 968 | 218 | 103 × 87 × 67 | 0.6 |

The initial intermonomer center of mass distance (d0, in angstrom), number of solvent water (SW) and solvent glucose (SG) molecules, initial dimensions of the simulation box, and the cumulative simulation times (Ttotal, in microseconds) are specified.

Trajectory Analysis

Secondary Structure

Secondary structural propensities for individual residues were obtained using the STRIDE algorithm,122 as implemented in VMD.123

Protein–Protein Interaction Energy

The nonbonded interaction energies (electrostatic and vdW) between the peptide units were calculated using the NAMD Energy plugin available in the NAMD package.112 The interaction energy, E, composed of electrostatic and vdW interactions, for a pair of atoms of charges qi and qj, separated by a distance rij, is given by

|

1 |

where the parameters σij, εij, and D are obtained from the force field.

SASA

SASA values were calculated using the VMD package123 by rolling a spherical probe of radius 1.4 Å over the protein residue surface.

Binding Free Energy

The absolute binding free energies between the two Aβ monomers were obtained using the MM-GBSA method, as implemented in the NAMD package.95,96 The calculation was performed using the single trajectory method on the dimer as well as each of the monomeric subunits constituting the complex. The total free energy of each of the components is defined as

| 2 |

where HMM, Gsolv-pol, Gsolv-np, and Sconfig represent the total internal energy, the polar solvation free energy, the nonpolar solvation free energy, and the configurational entropy, respectively. The internal energy, HMM, is composed of the bond, angle, dihedral, improper, electrostatic, and vdW energies. The solvent dielectric constant of water at 310 K was used to compute the polar solvation free energy.124 The nonpolar solvation free energy, Gsolv-np, is quantified as the product of the surface tension of water (γ = 0.0072) and the SASA of the solute. The binding free energy is estimated as the difference

| 3 |

The entropic changes are ignored as in previous recent studies.56,95,96,125 The binding free energy of the dimer complex is thus obtained as

| 4 |

where ΔEelectrostatic, ΔEvdW, and ΔEinternal are the changes in the electrostatic, vdW, and bonded energies, respectively.

Preferential Interaction Parameters

To obtain information about the enrichment or exclusion of solution species at the protein surface, we estimated the solute–solvent preferential interaction parameters. These parameters have provided profound insights on protein solvation in several earlier works.36,126−129 Accordingly, the time-averaged normalized preferential interaction parameters of solution species, water (POw), and glucose (Pglc) can be defined as

| 5 |

| 6 |

where nOw and nglc refer to the local number of water oxygen atoms and glucose molecules, respectively, located at a distance “r” from the heavy atoms of the protein; NOw and Nglc correspond to the total number of water oxygen atoms and glucose molecules in the simulation box, respectively. If the ratio Px(r) is greater than 1 in close proximity of the peptide, then the respective solvent species preferentially interacts with the peptide. Conversely, if the ratio is lower than 1, the solvent molecules are preferentially excluded from the surface of the peptide.

Acknowledgments

Computational resources were obtained from the CSIR 12th Five Year Plan “Multiscale Simulation and Modeling” project (MSM; project number CSC0129). S.M. acknowledges her Ph.D. fellowship provided by the Department of Biotechnology through the Bioinformatics National Certification (BINC) examination. Dr. Debashree Ghosh is thanked for her support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.7b00018.

Description of configurational entropy and tetrahedral order parameter calculation; g(r) plots of protein heavy atoms and water oxygen atoms (monomer and dimer); table with number of residue contacts; tabulated interpeptide contacts of the dimeric system; table of average Q and SASA/contact residue of the dimeric system (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Masters C. L.; Simms G.; Weinman N. A.; Multhaup G.; McDonald B. L.; Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985, 82, 4245–4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc A. Increased production of 4 kDa amyloid beta peptide in serum deprived human primary neuron cultures: possible involvement of apoptosis. J. Neurosci. 1995, 15, 7837–7846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busciglio J.; Gabuzda D. H.; Matsudaira P.; Yankner B. A. Generation of beta-amyloid in the secretory pathway in neuronal and nonneuronal cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993, 90, 2092–2096. 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright P. E.; Dyson H. J. Intrinsically unstructured proteins: re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 293, 321–331. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi H.; Tompa P. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins Display No Preference for Chaperone Binding In Vivo. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008, 4, e1000017 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chebaro Y.; Ballard A. J.; Chakraborty D.; Wales D. J. Intrinsically Disordered Energy Landscapes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10386 10.1038/srep10386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson H. J. Making Sense of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Biophys. J. 2016, 110, 1013–1016. 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. A.; Poirier M. A. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S10–S17. 10.1038/nm1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky V. N. Intrinsically disordered proteins from A to Z. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011, 43, 1090–1103. 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky V. N. Introduction to Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs). Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6557–6560. 10.1021/cr500288y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J.; Selkoe D. J. The Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress and Problems on the Road to Therapeutics. Science 2002, 297, 353–356. 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R.; Head E.; Thompson J. L.; McIntire T. M.; Milton S. C.; Cotman C. W.; Glabe C. G. Common Structure of Soluble Amyloid Oligomers Implies Common Mechanism of Pathogenesis. Science 2003, 300, 486–489. 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D. M.; Selkoe D. J. Aβ Oligomers—a decade of discovery. J. Neurochem. 2007, 101, 1172–1184. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao M. Q.; Tzeng Y. J.; Chang L. Y. X.; Huang H. B.; Lin T. H.; Chyan C. L.; Chen Y. C. The correlation between neurotoxicity, aggregative ability and secondary structure studied by sequence truncated Aβ peptides. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 1161–1165. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C.; Selkoe D. J. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 101–112. 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M.; Davis J.; Aucoin D.; Sato T.; Ahuja S.; Aimoto S.; Elliott J. I.; Van Nostrand W. E.; Smith S. O. Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-β1–42 oligomers to fibrils. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 561–567. 10.1038/nsmb.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibson C. L.; Rocca W. A.; Hanson V. A.; Cha R.; Kokmen E.; O’Brien P. C.; Palumbo P. J. Risk of Dementia among Persons with Diabetes Mellitus: A Population-based Cohort Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 145, 301–308. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haan M. N. Therapy Insight: type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2006, 2, 159–166. 10.1038/ncpneuro0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S.; Sato N.; Rakugi H.; Morishita R. Molecular mechanisms linking diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer disease: beta-amyloid peptide, insulin signaling, and neuronal function. Mol. BioSyst. 2011, 7, 1822–1827. 10.1039/c0mb00302f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accardi G.; Caruso C.; Colonna-Romano G.; Camarda C.; Monastero R.; Candore G. Can Alzheimer disease be a form of type 3 diabetes?. Rejuvenation Res. 2012, 15, 217–221. 10.1089/rej.2011.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biessels G. J.; Strachan M. W. J.; Visseren F. L. J.; Kappelle L. J.; Whitmer R. A. Dementia and cognitive decline in type 2 diabetes and prediabetic stages: towards targeted interventions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 246–255. 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini L.; Netzer W. J.; Greengard P.; Xu H. Does insulin dysfunction play a role in Alzheimer’s disease?. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2002, 23, 288–293. 10.1016/S0165-6147(02)02037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier C.; Gagnon M. Glucose regulation and cognitive functions: relation to Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. Behav. Brain Res. 1996, 75, 1–11. 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi M.; Yamagishi S.-i. Involvement of toxic AGEs (TAGE) in the pathogenesis of diabetic vascular complications and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2009, 16, 845–858. 10.3233/JAD-2009-0974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. H.; Du L. L.; Cheng X. S.; Jiang X.; Zhang Y.; Lv B. L.; Liu R.; Wang J. Z.; Zhou X. W. Glycation exacerbates the neuronal toxicity of β-amyloid. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e673 10.1038/cddis.2013.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.; Li X. H.; Tu Y.; Sun H. T.; Liang H. Q.; Cheng S. X.; Zhang S. Aβ-AGE aggravates cognitive deficit in rats via RAGE pathway. Neuroscience 2014, 257, 1–10. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana A. K.; Batkulwar K. B.; Kulkarni M. J.; Sengupta N. Glycation induces conformational changes in the amyloid-β peptide and enhances its aggregation propensity: molecular insights. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 31446–31458. 10.1039/C6CP05041G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.-X.; Rivas G.; Minton A. P. Macromolecular crowding and confinement: biochemical, biophysical, and potential physiological consequences. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008, 37, 375–397. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg B.; Ellis R. J.; Dobson C. M. Effects of macromolecular crowding on protein folding and aggregation. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 6927–6933. 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosen-Runge F.; Hennig M.; Zhang F.; Jacobs R. M. J.; Sztucki M.; Schober H.; Seydel T.; Schreiber F. Protein self-diffusion in crowded solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 11815–11820. 10.1073/pnas.1107287108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrio-Dupont M.; Foucault G.; Vacher M.; Devaux P. F.; Cribier S. Translational Diffusion of Globular Proteins in the Cytoplasm of Cultured Muscle Cells. Biophys. J. 2000, 78, 901–907. 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76647-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Li C.; Pielak G. J. Effects of Proteins on Protein Diffusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 9392–9397. 10.1021/ja102296k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix J. A.; Verkman A. S. Crowding Effects on Diffusion in Solutions and Cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008, 37, 247–263. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minton A. P. Implications of macromolecular crowding for protein assembly. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000, 10, 34–39. 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B. R.; Zhou Z.; Hu Q. L.; Chen J.; Liang Y. Mixed macromolecular crowding inhibits amyloid formation of hen egg white lysozyme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2008, 1784, 472–480. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F. F.; Ji L.; Dong X. Y.; Sun Y. Molecular Insight into the Inhibition Effect of Trehalose on the Nucleation and Elongation of Amyloid β-Peptide Oligomers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 11320–11329. 10.1021/jp905580j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. X. Influence of crowded cellular environments on protein folding, binding, and oligomerization: Biological consequences and potentials of atomistic modeling. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 1053–1061. 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breydo L.; Reddy K. D.; Piai A.; Felli I. C.; Pierattelli R.; Uversky V. N. The crowd you’re in with: Effects of different types of crowding agents on protein aggregation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2014, 1844, 346–357. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiga E.; Abriata L. A.; Piazza F.; Dal Peraro M. Dissecting the Effects of Concentrated Carbohydrate Solutions on Protein Diffusion, Hydration, and Internal Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 5310–5321. 10.1021/jp4126705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky V. N.; M. Cooper E.; Bower K. S.; Li J.; Fink A. L. Accelerated α-synuclein fibrillation in crowded milieu. FEBS Lett. 2002, 515, 99–103. 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatters D. M.; Minton A. P.; Howlett G. J. Macromolecular Crowding Accelerates Amyloid Formation by Human Apolipoprotein C-II. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 7824–7830. 10.1074/jbc.M110429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munishkina L. A.; Ahmad A.; Fink A. L.; Uversky V. N. Guiding Protein Aggregation with Macromolecular Crowding. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 8993–9006. 10.1021/bi8008399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munishkina L. A.; Cooper E. M.; Uversky V. N.; Fink A. L. The effect of macromolecular crowding on protein aggregation and amyloid fibril formation. J. Mol. Recognit. 2004, 17, 456–464. 10.1002/jmr.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magno A.; Caflisch A.; Pellarin R. Crowding Effects on Amyloid Aggregation Kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 3027–3032. 10.1021/jz100967z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q.; Fan J.-B.; Zhou Z.; Zhou B.-R.; Meng S.-R.; Hu J.-Y.; Chen J.; Liang Y. The Contrasting Effect of Macromolecular Crowding on Amyloid Fibril Formation. PLoS One 2012, 7, e36288 10.1371/journal.pone.0036288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B.; Xie J.; Wei L.; Li W. Macromolecular crowding modulates the kinetics and morphology of amyloid self-assembly by β-lactoglobulin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 53, 82–87. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latshaw D. C.; Cheon M.; Hall C. K. Effects of Macromolecular Crowding on Amyloid Beta (16–22) Aggregation Using Coarse-Grained Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 13513–13526. 10.1021/jp508970q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z.; Das P.; Shakhnovich E. I.; Zhou R. Collapse of Unfolded Proteins in a Mixture of Denaturants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18266–18274. 10.1021/ja3031505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P.; Xia Z.; Zhou R. Collapse of a Hydrophobic Polymer in a Mixture of Denaturants. Langmuir 2013, 29, 4877–4882. 10.1021/la3046252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnanakaran S.; Nussinov R.; García A. E. Atomic-Level Description of Amyloid β-Dimer Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2158–2159. 10.1021/ja0548337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgourakis N. G.; Yan Y.; McCallum S. A.; Wang C.; Garcia A. E. The Alzheimer’s Peptides Aβ40 and 42 Adopt Distinct Conformations in Water: A Combined MD/NMR Study. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 368, 1448–1457. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone M. G.; Hua L.; Soto P.; Zhou R.; Berne B. J.; Shea J. E. Role of Water in Mediating the Assembly of Alzheimer Amyloid-β Aβ16–22 Protofilaments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 11066–11072. 10.1021/ja8017303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.-S.; Bowman G. R.; Beauchamp K. A.; Pande V. S. Investigating How Peptide Length and a Pathogenic Mutation Modify the Structural Ensemble of Amyloid Beta Monomer. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 315–324. 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viet M. H.; Nguyen P. H.; Ngo S. T.; Li M. S.; Derreumaux P. Effect of the Tottori Familial Disease Mutation (D7N) on the Monomers and Dimers of Aβ40 and Aβ42. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 1446–1457. 10.1021/cn400110d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsmon-Raz Y.; Miller Y. Non-Amyloid-β Component of Human α-Synuclein Oligomers Induces Formation of New Aβ Oligomers: Insight into the Mechanisms That Link Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s Diseases. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 46–55. 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P.; Chacko A. R.; Belfort G. Alzheimer’s Protective Cross-Interaction between Wild-Type and A2T Variants Alters Aβ42 Dimer Structure. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 606–618. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco G.; De Simone A.; Arosio P.; Vendruscolo M.; Veglia G.; Dobson C. M. Structural Ensembles of Membrane-bound α-Synuclein Reveal the Molecular Determinants of Synaptic Vesicle Affinity. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27125 10.1038/srep27125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Jang H.; Ma B.; Tsai C.-J.; Nussinov R. Modeling the Alzheimer Aβ17–42 Fibril Architecture: Tight Intermolecular Sheet-Sheet Association and Intramolecular Hydrated Cavities. Biophys. J. 2007, 93, 3046–3057. 10.1529/biophysj.107.110700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Jang H.; Ma B.; Nussinov R. Annular Structures as Intermediates in Fibril Formation of Alzheimer Aβ17–42. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 6856–6865. 10.1021/jp711335b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Hu R.; Liang G.; Chang Y.; Sun Y.; Peng Z.; Zheng J. Structural and Energetic Insight into the Cross-Seeding Amyloid Assemblies of Human IAPP and Rat IAPP. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 7026–7036. 10.1021/jp5022246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Hu R.; Chen H.; Chang Y.; Gong X.; Liu F.; Zheng J. Interfacial interaction and lateral association of cross-seeding assemblies between hIAPP and rIAPP oligomers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 10373–10382. 10.1039/C4CP05658B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Hu R.; Chen H.; Chang Y.; Ma J.; Liang G.; Mi J.; Wang Y.; Zheng J. Polymorphic cross-seeding amyloid assemblies of amyloid-β and human islet amyloid polypeptide. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 23245–23256. 10.1039/C5CP03329B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P.; Nandel F. S.; Hansmann U. H. E. The Alzheimer β-amyloid (Aβ1–39) dimer in an implicit solvent. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 129, 195102 10.1063/1.3021062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M.; Hansmann U. H. E. Replica exchange molecular dynamics of the thermodynamics of fibril growth of Alzheimer’s Aβ42 peptide. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 135, 065101 10.1063/1.3617250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi W.; Wang W.; Abbott G.; Hansmann U. H. E. Stability of a Recently Found Triple-β-Stranded Aβ1-42 Fibril Motif. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 4548–4557. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b01724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Y.; Ma B.; Nussinov R. Polymorphism of Alzheimer’s Aβ17-42 (p3) Oligomers: The Importance of the Turn Location and Its Conformation. Biophys. J. 2009, 97, 1168–1177. 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Y.; Ma B.; Nussinov R. The Unique Alzheimer’s β-Amyloid Triangular Fibril Has a Cavity along the Fibril Axis under Physiological Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 2742–2748. 10.1021/ja1100273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baram M.; Atsmon-Raz Y.; Ma B.; Nussinov R.; Miller Y. Amylin-Aβ oligomers at atomic resolution using molecular dynamics simulations: a link between Type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 2330–2338. 10.1039/C5CP03338A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarco M. L.; Daggett V. From conversion to aggregation: Protofibril formation of the prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 2293–2298. 10.1073/pnas.0307178101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei G.; Mousseau N.; Derreumaux P. Computational Simulations of the Early Steps of Protein Aggregation. Prion 2007, 1, 3–8. 10.4161/pri.1.1.3969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Iwata K.; Lachenmann M. J.; Peng J. W.; Li S.; Stimson E. R.; Lu Y.-a.; Felix A. M.; Maggio J. E.; Lee J. P. The Alzheimer’s Peptide Aβ Adopts a Collapsed Coil Structure in Water. J. Struct. Biol. 2000, 130, 130–141. 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K. H.; Collver H. H.; Le Y. T. H.; Nagchowdhuri P.; Kenney J. M. Characterizations of distinct amyloidogenic conformations of the Aβ (1–40) and (1–42) peptides. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 353, 443–449. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein S. L.; Wyttenbach T.; Baumketner A.; Shea J. E.; Bitan G.; Teplow D. B.; Bowers M. T. Amyloid β-Protein: Monomer Structure and Early Aggregation States of Aβ42 and Its Pro19 Alloform. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 2075–2084. 10.1021/ja044531p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumketner A.; Bernstein S. L.; Wyttenbach T.; Bitan G.; Teplow D. B.; Bowers M. T.; Shea J. E. Amyloid β-protein monomer structure: A computational and experimental study. Protein Sci. 2006, 15, 420–428. 10.1110/ps.051762406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Ham S. Characterizing amyloid-beta protein misfolding from molecular dynamics simulations with explicit water. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 349–355. 10.1002/jcc.21628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana A. K.; Sengupta N. Adsorption Mechanism and Collapse Propensities of the Full-Length, Monomeric Aβ1-42 on the Surface of a Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 1889–1896. 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana A. K.; Jose J. C.; Sengupta N. Critical roles of key domains in complete adsorption of Aβ peptide on single-walled carbon nanotubes: insights with point mutations and MD simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 837–844. 10.1039/C2CP42933K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasica-Labouze J.; Nguyen P. H.; Sterpone F.; Berthoumieu O.; Buchete N.-V.; Coté S.; De Simone A.; Doig A. J.; Faller P.; Garcia A.; Laio A.; Li M. S.; Melchionna S.; Mousseau N.; Mu Y.; Paravastu A.; Pasquali S.; Rosenman D. J.; Strodel B.; Tarus B.; Viles J. H.; Zhang T.; Wang C.; Derreumaux P. Amyloid β Protein and Alzheimer’s Disease: When Computer Simulations Complement Experimental Studies. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3518–3563. 10.1021/cr500638n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barz B.; Olubiyi O. O.; Strodel B. Early amyloid β-protein aggregation precedes conformational change. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 5373–5375. 10.1039/C3CC48704K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel-Steger L.; Owen M. C.; Strodel B. An Account of Amyloid Oligomers: Facts and Figures Obtained from Experiments and Simulations. ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 657–676. 10.1002/cbic.201500623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana A. K.; Sengupta N. Aβ self-association and adsorption on a hydrophobic nanosurface: competitive effects and the detection of small oligomers via electrical response. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 269–279. 10.1039/C4SM01845A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K.; Condron M. M.; Teplow D. B. Structure-neurotoxicity relationships of amyloid β-protein oligomers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 14745–14750. 10.1073/pnas.0905127106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Y.; Ma B.; Nussinov R. Polymorphism in Alzheimer Aβ Amyloid Organization Reflects Conformational Selection in a Rugged Energy Landscape. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4820–4838. 10.1021/cr900377t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar G. M.; Li S.; Mehta T. H.; Garcia-Munoz A.; Shepardson N. E.; Smith I.; Brett F. M.; Farrell M. A.; Rowan M. J.; Lemere C. A.; Regan C. M.; Walsh D. M.; Sabatini B. L.; Selkoe D. J. Amyloid-β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 837–842. 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D. M.; Hartley D. M.; Kusumoto Y.; Fezoui Y.; Condron M. M.; Lomakin A.; Benedek G. B.; Selkoe D. J.; Teplow D. B. Amyloid β-Protein Fibrillogenesis: structure and biological activity of protofibrillar intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 25945–25952. 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Nuallain B.; Freir D. B.; Nicoll A. J.; Risse E.; Ferguson N.; Herron C. E.; Collinge J.; Walsh D. M. Amyloid β-Protein Dimers Rapidly Form Stable Synaptotoxic Protofibrils. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 14411–14419. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3537-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne V. L.; Perez K. A.; Pike K. E.; Kok W. M.; Rowe C. C.; White A. R.; Bourgeat P.; Salvado O.; Bedo J.; Hutton C. A.; Faux N. G.; Masters C. L.; Barnham K. J. Blood-borne amyloid-β dimer correlates with clinical markers of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 6315–6322. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5180-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong S. H.; Ham S. Atomic-level investigations on the amyloid-β dimerization process and its driving forces in water. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 1573–1575. 10.1039/C2CP23326F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X.; Bora R. P.; Barman A.; Singh R.; Prabhakar R. Dimerization of the Full-Length Alzheimer Amyloid β-Peptide (Aβ42) in Explicit Aqueous Solution: A Molecular Dynamics Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 4405–4416. 10.1021/jp210019h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Z.; Roychaudhuri R.; Condron M. M.; Teplow D. B.; Lyubchenko Y. L. Mechanism of amyloid β-protein dimerization determined using single-molecule AFM force spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2880 10.1038/srep02880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.; Buettner R.; Yuan Y. C.; Yip R.; Horne D.; Jove R.; Vaidehi N. Molecular dynamics simulations of the conformational changes in signal transducers and activators of transcription, Stat1 and Stat3. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2009, 28, 347–356. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose J. C.; Chatterjee P.; Sengupta N. Cross Dimerization of Amyloid-β and αSynuclein Proteins in Aqueous Environment: A Molecular Dynamics Simulations Study. PLoS One 2014, 9, e106883 10.1371/journal.pone.0106883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong S. H.; Ham S. Impact of chemical heterogeneity on protein self-assembly in water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 7636–7641. 10.1073/pnas.1120646109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté S.; Laghaei R.; Derreumaux P.; Mousseau N. Distinct Dimerization for Various Alloforms of the Amyloid-Beta Protein: Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and Aβ1–40(D23N). J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 4043–4055. 10.1021/jp2126366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara-Jaque A.; Comer J.; Monsalve L.; González-Nilo F. D.; Sandoval C. Computationally Efficient Methodology for Atomic-Level Characterization of Dendrimer–Drug Complexes: A Comparison of Amine- and Acetyl-Terminated PAMAM. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 6801–6813. 10.1021/jp4000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorham R. D. Jr.; Rodriguez W.; Morikis D. Molecular Analysis of the Interaction between Staphylococcal Virulence Factor Sbi-IV and Complement C3d. Biophys. J. 2014, 106, 1164–1173. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke H.; Kiel C.; Case D. A. Insights into Protein-Protein Binding by Binding Free Energy Calculation and Free Energy Decomposition for the Ras–Raf and Ras–RalGDS Complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 330, 891–913. 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. A.; Lindquist S. Multiple Effects of Trehalose on Protein Folding In Vitro and In Vivo. Mol. Cell 1998, 1, 639–648. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Barkhordarian H.; Emadi S.; Park C. B.; Sierks M. R. Trehalose differentially inhibits aggregation and neurotoxicity of beta-amyloid 40 and 42. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005, 20, 74–81. 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatova Z.; Gierasch L. M.. Chapter Twenty-One – Effects of Osmolytes on Protein Folding and Aggregation in Cells. In Methods in Enzymology; Dieter H., Helmut S., Eds.; Academic Press, 2007; Vol. 428, pp 355–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrela N.; Franquelim H. G.; Lopes C.; Tavares E.; Macedo J. A.; Christiansen G.; Otzen D. E.; Melo E. P. Sucrose prevents protein fibrillation through compaction of the tertiary structure but hardly affects the secondary structure. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2015, 83, 2039–2051. 10.1002/prot.24921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanc B.; Cruz L.; Ding F.; Sammond D.; Khare S.; Buldyrev S. V.; Stanley H. E.; Dokholyan N. V. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Amyloid β Dimer Formation. Biophys. J. 2004, 87, 2310–2321. 10.1529/biophysj.104.040980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlitter J. Estimation of absolute and relative entropies of macromolecules using the covariance matrix. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993, 215, 617–621. 10.1016/0009-2614(93)89366-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chong S. H.; Ham S. Interaction with the Surrounding Water Plays a Key Role in Determining the Aggregation Propensity of Proteins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3961–3964. 10.1002/anie.201309317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J.; Komatsu H.; Kim Y. S.; Liu L.; Hochstrasser R. M.; Axelsen P. H. Intrinsic Structural Heterogeneity and Long-Term Maturation of Amyloid β Peptide Fibrils. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 1236–1243. 10.1021/cn400092v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya S.; Mukhopadhyay S. Ordered Water within the Collapsed Globules of an Amyloidogenic Intrinsically Disordered Protein. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 9191–9198. 10.1021/jp504076a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong S. H.; Ham S. Distinct Role of Hydration Water in Protein Misfolding and Aggregation Revealed by Fluctuating Thermodynamics Analysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 956–965. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal V.; Arya S.; Mukhopadhyay S. Confined Water in Amyloid-Competent Oligomers of the Prion Protein. ChemPhysChem 2016, 17, 2804–2807. 10.1002/cphc.201600440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errington J. R.; Debenedetti P. G. Relationship between structural order and the anomalies of liquid water. Nature 2001, 409, 318–321. 10.1038/35053024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M.; Nayar D.; Chakravarty C.; Bandyopadhyay S. Comparison of hydration behavior and conformational preferences of the Trp-cage mini-protein in different rigid-body water models. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 32796–32813. 10.1039/C6CP04634G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatua P.; Jose J. C.; Sengupta N.; Bandyopadhyay S. Conformational features of the Aβ42 peptide monomer and its interaction with the surrounding solvent. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 30144–30159. 10.1039/C6CP04925G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalé L.; Skeel R.; Bhandarkar M.; Brunner R.; Gursoy A.; Krawetz N.; Phillips J.; Shinozaki A.; Varadarajan K.; Schulten K. NAMD2: Greater Scalability for Parallel Molecular Dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1999, 151, 283–312. 10.1006/jcph.1999.6201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mackerell A. D. Jr. Empirical force fields for biological macromolecules: Overview and issues. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1584–1604. 10.1002/jcc.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L.; Chandrasekhar J.; Madura J. D.; Impey R. W.; Klein M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. 10.1063/1.445869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Pacheco M.; Strodel B. Comparison of force fields for Alzheimer’s A β42: A case study for intrinsically disordered proteins. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 174–185. 10.1002/pro.3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller S. E.; Zhang Y.; Pastor R. W.; Brooks B. R. Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: The Langevin piston method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 4613–4621. 10.1063/1.470648. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Essmann U.; Perera L.; Berkowitz M. L.; Darden T.; Lee H.; Pedersen L. G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 8577–8593. 10.1063/1.470117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckaert J. P.; Ciccotti G.; Berendsen H. J. C. Numerical integration of the Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977, 23, 327–341. 10.1016/0021-9991(77)90098-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli S.; Esposito V.; Vangone P.; van Nuland N. A. J.; Bonvin A. M. J. J.; Guerrini R.; Tancredi T.; Temussi P. A.; Picone D. The α-to-β Conformational Transition of Alzheimer’s Aβ-(1–42) Peptide in Aqueous Media is Reversible: A Step by Step Conformational Analysis Suggests the Location of β Conformation Seeding. ChemBioChem 2006, 7, 257–267. 10.1002/cbic.200500223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osapay K.; Case D. A. A new analysis of proton chemical shifts in proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 9436–9444. 10.1021/ja00025a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez L.; Andrade R.; Birgin E. G.; Martínez J. M. Packmol: A package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2157–2164. 10.1002/jcc.21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinig M.; Frishman D. STRIDE: a web server for secondary structure assignment from known atomic coordinates of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, W500–W502. 10.1093/nar/gkh429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández D. P.; Mulev Y.; Goodwin A. R. H.; Sengers J. M. H. L. A Database for the Static Dielectric Constant of Water and Steam. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1995, 24, 33–70. 10.1063/1.555977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Xiao X.; Yuan Y.; Guo Y.; Li M.; Pu X. Probing Immobilization Mechanism of alpha-chymotrypsin onto Carbon Nanotube in Organic Media by Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9297 10.1038/srep09297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerbret A.; Bordat P.; Affouard F.; Hédoux A.; Guinet Y.; Descamps M. How Do Trehalose, Maltose, and Sucrose Influence Some Structural and Dynamical Properties of Lysozyme? Insight from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 9410–9420. 10.1021/jp071946z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerbret A.; Affouard F.; Bordat P.; Hédoux A.; Guinet Y.; Descamps M. Molecular dynamics simulations of lysozyme in water/sugar solutions. Chem. Phys. 2008, 345, 267–274. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2007.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N.; Liu F.-F.; Dong X.-Y.; Sun Y. Molecular Insight into the Counteraction of Trehalose on Urea-Induced Protein Denaturation Using Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 7040–7047. 10.1021/jp300171h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S.; Paul S. Molecular Insights into the Role of Aqueous Trehalose Solution on Temperature-Induced Protein Denaturation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 1598–1610. 10.1021/jp510423n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]