Abstract

Objective

Although vasodilators are used in acute heart failure (AHF) management, there have been no clear supportive evidence regarding their routine use. Recent European guidelines recommend systolic blood pressure (SBP) reduction in the range of 25% during the first few hours after diagnosis. This study aimed to examine clinical and prognostic significance of early treatment with intravenous vasodilators in relation to their subsequent SBP reduction in hospitalised AHF.

Methods

We performed post hoc analysis of 1670 consecutive patients enrolled in the Registry Focused on Very Early Presentation and Treatment in Emergency Department of Acute Heart Failure. Intravenous vasodilator use within 6 hours of hospital arrival and subsequent SBP changes were analysed. Outcomes were gauged by 1-year mortality and diuretic response (DR), defined as total urine output 6 hours posthospital arrival per 40 mg furosemide-equivalent diuretic use.

Results

Over half of the patients (56.0%) were treated with intravenous vasodilators within the first 6 hours. In this vasodilator-treated cohort, 554 (59.3%) experienced SBP reduction ≤25%, while 381 (40.7%) experienced SBP reduction >25%. In patients experiencing ≤25% drop in SBP, use of vasodilator was associated with greater DR compared with no vasodilators (p<0.001). Moreover, vasodilator treatment with ≤25% drop in SBP was independently associated with lower all-cause mortality compared with those treated without vasodilators (adjusted HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.96, p=0.028).

Conclusions

Intravenous vasodilator therapy was associated with greater DR and lower mortality, provided SBP reduction was less than 25%. Our results highlight the importance in early administration of intravenous vasodilators without causing excess SBP reduction in AHF management.

Clinical trial registration

URL: http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/ Unique identifier: UMIN000014105.

Keywords: heart failure, heart failure treatment, vasodilators

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Intravenous vasodilators are recommended in acute heart failure (AHF) management, but there have been no clear supportive evidence regarding their routine use. Excessive blood pressure reduction is associated with worse outcomes in patients with AHF.

What does this study add?

Early therapy using intravenous vasodilators with subsequent blood pressure reduction less than 25% from baseline was associated with better diuretic response and prognosis in hospitalised AHF compared with those treated without vasodilators.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Our results highlight the importance in early administration of intravenous vasodilators without causing excess systolic blood pressure reduction in AHF management.

Introduction

Vasodilators optimise preload and afterload by decreasing venous and arterial tone and consequently lower systolic blood pressure (SBP) and increase stroke volume.1–3 Although it is common clinical practice to use vasodilators in the management of acute heart failure (AHF) in accordance with the current guidelines,2 4 there has been no clear supportive evidence regarding the routine use of intravenous vasodilators and clinical trials currently performed resulted in neutral results in terms of prognostic effect.5 6 This is in part due to the variability of patients’ baseline volume and perfusion status and their propensity to maintain adequate circulation by intravascular refill following aggressive diuresis. In addition, most of the previous AHF studies have enrolled patients relatively late timing,7–12 and role of vasodilators in very acute phase in patients with AHF remains unclear. While most studies have a lower SBP threshold to withhold vasodilator therapy, there are unavoidable concerns regarding the negative prognostic impact of excessive SBP fall accompanying vasodilator use—in many cases reactive and likely too late in preventing adverse consequences. Indeed, some studies have shown that SBP fall in the acute setting of AHF was associated with worse renal and clinical outcomes.13–15 As a result, the latest European guidelines recommend their use in targeting a range of SBP reductions within 25% from baseline during the first few hours.2 Nevertheless, this cut-off value is not based on enough evidence, and the clinical and prognostic impact of SBP reduction by acute-phase intravenous vasodilators has not been carefully investigated. Herein, we examine the clinical and prognostic impact of very early treatment with intravenous vasodilators in relation to SBP reduction in hospitalised patients with AHF.

Methods

Study population

The Registry Focused on Very Early Presentation and Treatment in Emergency Department of Acute Heart Failure (REALITY-AHF) study was designed to determine the prognostic impact of time-to-treatment for AHF performed in the very acute phase in the emergency department. The study design and primary results have been reported elsewhere in detail, with unique capture of data at the earliest clinical encounter prior to administration of intravenous diuretics that provides the feasibility for our post hoc analysis.16 Briefly, the REALITY-AHF study was a multicenter prospective registry, which included 1682 consecutive hospitalised patients diagnosed with AHF in the emergency department within 3 hours of the first evaluation by caregivers. Exclusion criteria were: (1) treatment with an intravenous drug performed prior to ED arrival, (2) previous heart transplantation, (3) on either chronic peritoneal dialysis or haemodialysis, (4) acute myocarditis and (5) acute coronary syndrome requiring emergent/urgent revascularisation. Patients with missing brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal-proBNP data and those with a BNP level <100 pg/mL or N-terminal-proBNP level <300 pg/mL at baseline were also excluded.

Vasodilator use and SBP reduction in acute phase

Each patient enrolled in the REALITY-AHF study underwent a detailed baseline assessment including physical examination, vital signs, haemodynamic assessment if needed, echocardiography, medical history and medications. The ‘time zero’ was set at the exact time of emergency department arrival, and SBP was measured and recorded at baseline, 90 min, 6 hours, 24 hours and 48 hours after patients’ emergency department arrival.

As our main purpose of this study is to investigate the association between vasodilator use and SBP reduction in the very acute phase of AHF management, we focused on 6-hour period from patients’ emergency department arrival. SBP reduction was defined as per cent reduction in SBP from baseline to at 90 min or 6 hours, whichever was lower. According to the latest European guidelines recommendation,2 patients were categorised into three groups: no vasodilator treatment, vasodilator treatment yielding a BP reduction of ≤25% and vasodilator treatment yielding a BP reduction of >25% within 6 hours of emergency department arrival.2

Outcomes

We evaluated diuretic response (DR) and 1 year all-cause mortality as outcomes. The DR was defined as a total urine output achieved at 6 hours from the patient’s hospital arrival per 40 mg furosemide-equivalent diuretics use.16 Oral furosemide was converted to half dose of intravenous furosemide. The doses of other oral loop diuretics that were considered equivalent to 40 mg intravenous furosemide were 10 mg torsemide and 60 mg azosemide.

The 1 year all-cause mortality was defined from the day of admission. Patient status was prospectively tracked for all patients with medical chart review and confirmed by follow-up contact. For those followed-up in other institution from where the patient was registered, prognostic data were obtained from telephone interviews by the medical records department of other medical facilities caring for the patient or from information given by family members.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are shown as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables are expressed as mean and SD or median and IQR where appropriate. The relationship between groups and baseline characteristics were tested using the one-way analysis of variance, Kruskal-Wallis or Χ2 tests, where appropriate. When necessary, variables were transformed for further analysis. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model with the following risk-adjusting variables was constructed to estimate the adjusted HR, including age, gender, baseline SBP, heart rate at admission, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), history of diabetes mellitus, history of heart failure, serum creatinine, haemoglobin, sodium levels, blood urea nitrogen, BNP levels, prescription of beta-blocker and ACE inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor antagonist (ARB) at admission. Graphical inspection of Schoenfield residuals plotted against time was performed to ensure proportional hazards assumption was not violated. All variables were selected a priori as they were either predictors of risk in heart failure or because of their ability to confound the results. We performed exploratory analysis to evaluate the association between SBP fall within 6 hours of emergency department arrival and 1 year all-cause death. We used a restricted cubic spline to visualise adjusted HR calculated by multivariable Cox regression model. Same variables as used in the Cox regression model were used for adjustment in restricted cubic spline model. Knots were placed at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles (−41.6%, −16.7% and +4.3%, respectively). Further, interaction analyses among baseline SBP, SBP fall within 6 hours and 1-year mortality were performed. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software R (V.3.1.2, Vienna, Austria). A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

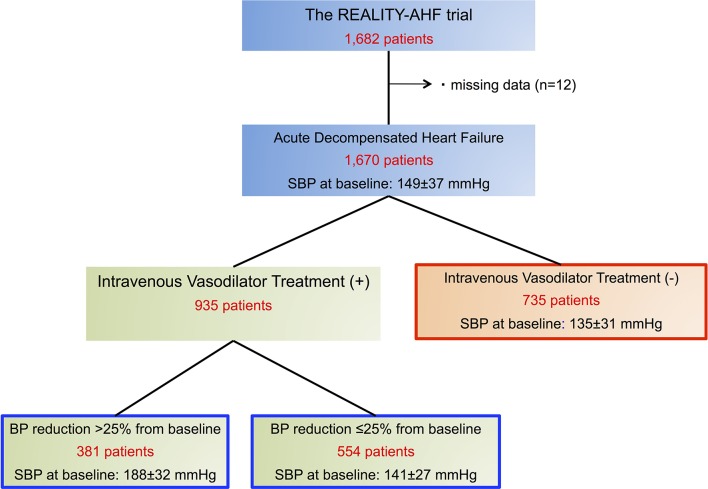

Overall, median SBP reduction rate from baseline to 6 hours from hospital arrival was 17.4 (IQR 5.1–20)%. During the first 6 hours after patient arrival in hospital, intravenous vasodilator therapy was performed in 935 patients (56.0%). In this vasodilator-treated cohort, 554 (59.3%) exhibited a SBP reduction of ≤25% from baseline, while 381 (40.7%) experienced a SBP reduction of >25% (figure 1). Comparisons of baseline characteristics among these groups are provided in table 1. Patients treated with vasodilator yielding a SBP reduction >25% had significantly higher blood pressure (BP) and heart rate at baseline and higher prevalence of hypertension. Although age and BNP levels were similar among the three groups, serum creatinine levels were significantly higher in patients treated with vasodilators yielding a SBP reduction of ≤25%.

Figure 1.

Study patient flow. REALITY-AHF, Registry Focused on Very Early Presentation and Treatment in Emergency Department of Acute Heart Failure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variables | No vasodilators | Vasodilator and ≤25% BP reduction | Vasodilator and >25% BP reduction | P values |

| n=735 | n=554 | n=381 | ||

| Age, years | 78±12 | 77±13 | 77±12 | 0.191 |

| Male | 390 (53.1) | 329 (59.4) | 207 (54.3) | 0.068 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 411 (56.7) | 307 (56.0) | 220 (59.1) | 0.626 |

| Pulmonary rate | 440 (60.1) | 344 (62.2) | 314 (82.4) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral oedema | 503 (68.6) | 410 (74.0) | 230 (60.5) | <0.001 |

| Baseline systolic BP, mm Hg | 135±31 | 141±27 | 188±32 | <0.001 |

| Baseline diastolic BP, mm Hg | 76±20 | 79±21 | 104±28 | <0.001 |

| Baseline heart rate, bpm | 94±28 | 94±28 | 109±27 | <0.001 |

| Heart rhythm | ||||

| Sinus rhythm | 362 (49.6) | 300 (54.2) | 244 (64.2) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 286 (39.2) | 191 (34.5) | 112 (29.5) | |

| Others | 82 (11.2) | 62 (11.2) | 24 (6.3) | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | ||||

| 35 | 262 (38.8) | 201 (37.6) | 128 (36.1) | 0.519 |

| 35–50 | 189 (28.0) | 149 (27.9) | 116 (32.7) | |

| 50 | 225 (33.3) | 184 (34.5) | 111 (31.3) | |

| Prior history of heart failure | 408 (55.6) | 285 (51.4) | 155 (40.7) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 445 (60.5) | 378 (68.5) | 297 (78.0) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 242 (32.9) | 219 (39.7) | 155 (40.7) | 0.01 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 78 (10.6) | 36 (6.6) | 37 (9.8) | 0.038 |

| Coronary artery disease | 188 (25.6) | 188 (34.1) | 126 (33.1) | 0.002 |

| Medications | ||||

| Loop diuretics | 413 (56.3) | 292 (53.1) | 139 (37.0) | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonist | 0.44 (0.50) | 0.46 (0.50) | 0.50 (0.50) | 0.171 |

| Beta blocker | 314 (43.0) | 243 (43.9) | 155 (41.2) | 0.713 |

| MR angiography | 207 (28.2) | 105 (19.0) | 59 (15.5) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| White cell count | 7050 (5600, 9400) | 7300 (5600, 9575) | 8900 (6900, 11 800) | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin | 11.6±2.2 | 11.6±2.34 | 12.1±2.41 | <0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 31 (23, 47) | 30 (22, 46) | 32 (24, 48) | 0.687 |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 22 (13, 37) | 22 (14, 37) | 21 (14, 36) | 0.501 |

| Creatinine | 1.08 (0.81, 1.56) | 1.22 (0.87, 1.78) | 1.09 (0.84, 1.44) | 0.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 25 (18, 36) | 26 (19, 39) | 23 (17, 31) | <0.001 |

| Sodium | 138±5 | 139±5 | 140±4 | <0.001 |

| Glucose | 155±73 | 160±75 | 199±86 | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein | 0.75 (0.22, 2.24) | 0.85 (0.26, 2.55) | 0.45 (0.13, 1.21) | <0.001 |

| Brain natriuretic peptide | 710 (452, 1312) | 794 (432, 1556) | 745 (457, 1150) | 0.086 |

BP, blood pressure.

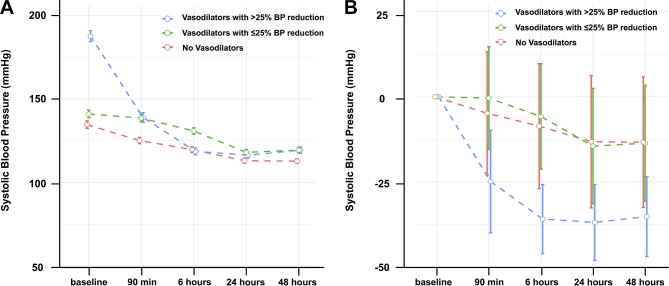

Blood pressure changes and diuretic response

In the overall registry, the mean SBP was 149±37 mm Hg at baseline and 123±23 mm Hg at 6 hours from hospital arrival. Although patients treated with vasodilator yielding a SBP reduction of >25% had the highest baseline SBP among the three groups (p<0.001), SBP at 6 hours from baseline was the highest in patients treated with vasodilator yielding a SBP reduction of ≤25% (p<0.001, figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of changes in systolic blood pressure among patients not receiving intravenous vasodilator therapy and those receiving vasodilators yielding blood pressure (BP) reductions >25% and ≤25%.

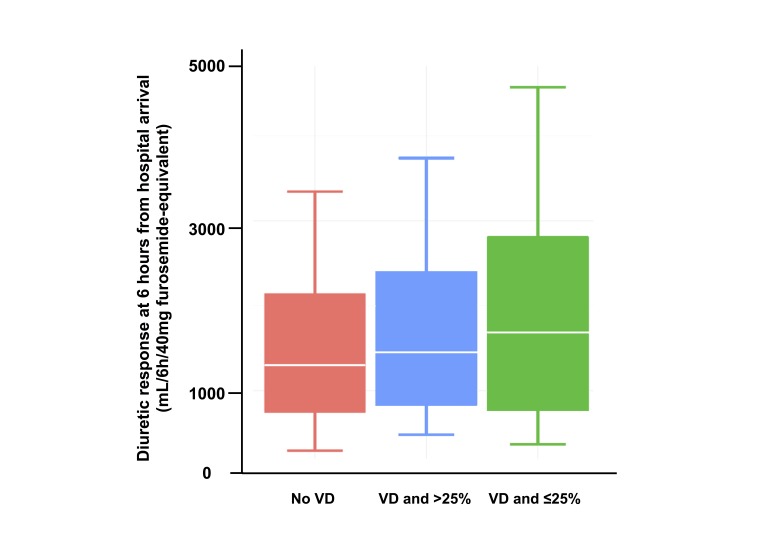

Patients treated with vasodilators yielding a SBP reduction of ≤25% showed significantly better DR than the other two groups (p<0.001, figure 3). Furthermore, vasodilator therapy yielding a SBP reduction of ≤25% (p<0.001) was associated with greater DR compared with those treated without vasodilators even after adjusting for confounders (table 2). However, no significant difference in DR was observed for patients with >25% drop in SBP compared with those without vasodilator treatment (p=0.915).

Figure 3.

Comparisons of diuretic response at 6 hours from hospital arrival.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariable linear regression for diuretic response at 6 hours from baseline

| Groups | Univariate linear regression for diuretic response at 6 hours | Multivariable linear regression for diuretic response at 6 hours | ||||

| B coefficient (95% CI) | t value | P values | B coefficient (95% CI) | t value | P values | |

| No vasodilators | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Vasodilator and≤25% SBP reduction | 459.4 (254.8 to 664.1) | 4.40 | <0.001 | 499.2 (268.9 to 729.5) | 4.26 | <0.001 |

| Vasodilator and>25% SBP reduction | 211.6 (−10.8 to 434.0) | 1.87 | 0.062 | −12.9 (−249.6 to 223.9) | −0.107 | 0.915 |

SBP, systolic blood pressure.

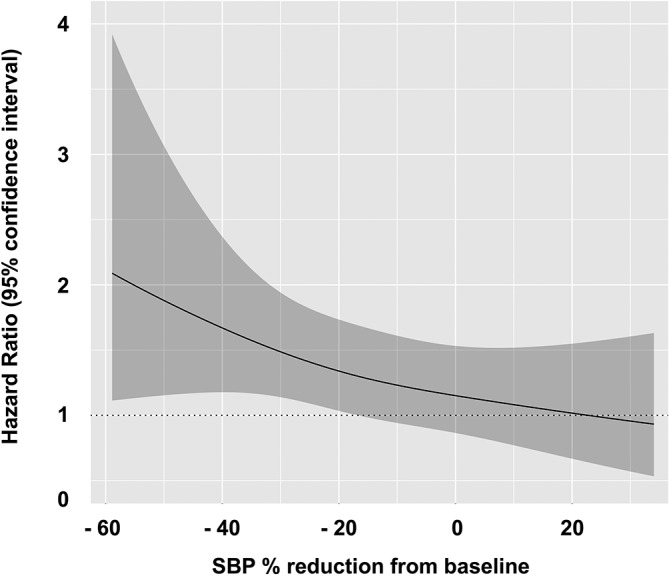

Blood pressure changes and mortality

Patient status at 1 year was obtained in 92.8% of all the patients. During a follow-up period of 1 year, 346 (19.7%) deaths were observed. The figure 4 depicts the continuous relationship between SBP changes from baseline to 6 hours and 1-year mortality. We observed that greater SBP reduction from baseline was associated with higher 1-year mortality. Furthermore, patients treated with vasodilators yielding SBP reduction ≤25% were associated with lower all-cause mortality compared with those treated without vasodilators, even after adjusting for confounders (adjusted HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.96, p=0.028, table 3). In contrast, those experienced >25% reduction in BP was not associated with lower all-cause mortality.

Figure 4.

The continuous association of systolic blood pressure reduction rate and all-cause mortality.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariable Cox regression for 1 year all-cause mortality

| Groups | Univariate Cox | Multivariable Cox | ||||

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P values | |

| No vasodilators | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Vasodilator and ≤25% SBP reduction | 0.69 | 0.54 to 0.99 | 0.003 | 0.74 | 0.57 to 0.96 | 0.028 |

| Vasodilator and >25% SBP reduction | 0.54 | 0.40 to 0.73 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.66 to 1.44 | 0.911 |

SBP, systolic blood pressure.

As an exploratory analysis, we evaluated the association between adjusted HR for 1-year mortality and SBP reduction during the first 6 hours from baseline. There was no statistically significant interaction between baseline SBP and SBP reduction (as a continuous scale) (p for interaction=0.909) and with/without vasodilator treatment and SBP reduction (p for interaction=0.692) on 1-year mortality.

Discussion

The current post hoc analysis of the REALITY-AHF study investigated the association between intravenous vasodilator therapy in the very acute phase in relation to accompanying SBP fall, the DR and 1-year mortality in 1670 hospitalised patients with AHF. The major finding of this study was that early intravenous vasodilator therapy was associated with greater DR and reduced 1-year mortality provided that the reduction of SBP from baseline was not higher than 25%, which supports the latest European guideline recommendations.2 Our results highlight the need to focus on careful patient selection and treatment monitoring with vasodilator use to achieve the most optimal outcomes.

The role of vasodilators in the management of AHF is pivotal.17 18 Traditional vasodilators such as nitrates are the second most commonly (after diuretics) administered drug category in the management of AHF.19–24 Intravenous vasodilators lead to afterload reduction, vascular redistribution and consequently to the relief of symptoms such as dyspnoea.17 A recent meta-analysis demonstrated similar improvement of left-sided and right-sided filling pressures by vasodilators or inotropes in patients with AHF with reduced LVEF.25 According to the guidelines, BP reduction and the use of intravenous vasodilators combined with diuretics for the relief of dyspnoea is recommended in patients admitted with AHF, in the absence of hypotension.2 4 However, few studies have focused on understanding the clinical impact of SBP reduction via the short-term use of intravenous vasodilators early in the course of AHF management.13 Although the routine use of intravenous vasodilators in the acute phase can lower BP and improve short-term symptoms in patients with AHF, it does not influence long-term outcomes.7–12 26 The present analysis highlights the fact that early administration of intravenous vasodilators in patients with AHF may be accompanied by favourable 1-year survival, provided that the SBP fall during treatment does not exceed the 25% compared with its baseline values.

Arterial dilating effects of vasodilators can be useful in patients with heart failure with higher peripheral arterial tone (ie, hypertensive patients), and venous dilating actions may exhibit favourable results in patients with heart failure with increased ventricular preload.27 However, the contributory role of vasodilators to the management of AHF may be offset by an unfavourable effect of SBP reduction.25 A recent study demonstrated that a greater early fall in SBP within the first 48 hours after hospitalisation for AHF was an independent predictor of worsening renal function which correlated with higher 60-day and 180-day mortality.15 Furthermore, poor DR in AHF has been shown to be independently associated with low baseline SBP, renal impairment and adverse outcomes.28–30 Thus, although vasodilators manifest beneficial haemodynamic effects when administered in patients with AHF with increased arterial tone, an excessive reduction of SBP may cause low organ perfusion, such as renal hypoperfusion, and consequently adverse outcomes, whereas a reasonable SBP reduction (ie, in the range of 25%) may lead to reduced afterload and accordingly to increased cardiac output. Interestingly, in the present analysis, patients treated with vasodilator yielding a SBP reduction of ≤25% exhibited a greater DR compared with those without vasodilator treatment. The balance between these favourable and unfavourable effects of vasodilators in the acute setting seems to be of high clinical importance, as a significant fall in SBP and/or hypotensive episodes may cancel their beneficial effects: therefore, the use of vasodilators may be accompanied by neutral or even adverse outcomes. The fact that 40.7% in the registry experience rather profound reduction in SBP (>25% from baseline) following vasodilator therapy suggests that such intricate balance of preload and afterload to relieve congestion as well as maintain circulatory perfusion can be difficult in a large subset of patients with AHF especially with concomitant use of vasodilator therapy.

Another possible explanation for the favourable prognostic impact of vasodilator treatment in our study is that we investigated the early use of intravenous vasodilator (<6 hours of emergency department arrival). Previous studies suggested that the efficacy of treatment for AHF may be time-dependent.16 31–34 The latest guidelines recommend early management and emphasise the time-to-treatment concept in the management of AHF.2 We have recently reported favourable prognostic impacts of early diuretic treatment in patients with AHF,16 and time-to-treatment concept for AHF may be also applicable to intravenous vasodilator use. One simple way to explain this observation is the fact that earlier administration of vasodilator does not have to confront the excessive intravascular volume depletion common with aggressive intravenous diuretic therapy. Hence, optimal balancing of congestion relief can be achieved without compromising organ perfusion, which is far more likely when plasma refill rate is low. The RELAITY-AHF study which focused on the very acute phase treatment for AHF is a unique dataset which enabled us to evaluate time-dependent treatment efficacies in the management of AHF. Our results highlight the importance of intravenous vasodilator administration, provided the SBP reduction is within the range of 25% in the early treatment for AHF.

Limitations

There are several limitations inherent in the post hoc retrospective analysis design. First, we do not have information regarding vasodilator dosage, nor did we analyse the specific type of vasodilators. Second, this was not a predefined analysis, but a post hoc analysis from a registry, and thus treatment with vasodilators was not randomised. Third, although all the three groups had follow-up rate higher than 90%, relatively low rate in the group of vasodilator use and ≤25% SBP reduction may influence the results. Finally, despite covariate adjustment, we cannot exclude the influence of other measured and unmeasured confounders. Nonetheless, REALITY-AHF was a well-designed and large-scale data set, which enabled us to assess the trajectory of BP in the very acute phase of AHF, and to gain a new perspective on the role of vasodilators in AHF management.

Conclusions

Intravenous vasodilator therapy was associated with greater DR and lower mortality, provided the SBP reduction subsequently achieved was less than 25%. Our results highlight the clinical and prognostic importance of the timely use of intravenous vasodilators which do not cause excessive SBP lowering in the treatment of AHF.

Footnotes

Contributors: TK and YM were responsible for the study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of manuscript. All authors contributed to the acquisition of data. AX, WT and YF contributed to the critical revision.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: YM is supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Overseas Research Fellowships and received an honorarium from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board in each hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Piper S, McDonagh T. The role of intravenous vasodilators in acute heart failure management. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:827–34. 10.1002/ejhf.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2129–200. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hollenberg SM. Vasodilators in acute heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2007;12:143–7. 10.1007/s10741-007-9017-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2013;128:1810–52. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mebazaa A, Yilmaz MB, Levy P, et al. Recommendations on pre-hospital & early hospital management of acute heart failure: a consensus paper from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, the European Society of Emergency Medicine and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. Eur J Heart Fail 2015;17:544–58. 10.1002/ejhf.289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cotter G, Davison B. Intravenous therapies in acute heart failure–lack of effect or lack of well powered studies? Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:355–7. 10.1002/ejhf.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mebazaa A, Motiejunaite J, Gayat E, et al. Long-term safety of intravenous cardiovascular agents in acute heart failure: results from the european society of cardiology heart failure long-term registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20 10.1002/ejhf.991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel PA, Heizer G, O’Connor CM, et al. Hypotension during hospitalization for acute heart failure is independently associated with 30-day mortality: findings from ASCEND-HF. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:918–25. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Packer M, Colucci W, Fisher L, et al. Effect of levosimendan on the short-term clinical course of patients with acutely decompensated heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2013;1:103–11. 10.1016/j.jchf.2012.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O’Connor CM, Starling RC, Hernandez AF, et al. Effect of nesiritide in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med 2011;365:32–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1100171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elkayam U, Tasissa G, Binanay C, et al. Use and impact of inotropes and vasodilator therapy in hospitalized patients with severe heart failure. Am Heart J 2007;153:98–104. 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aaronson KD, Sackner-Bernstein J. Risk of death associated with nesiritide in patients with acutely decompensated heart failure. JAMA 2006;296:1465–6. 10.1001/jama.296.12.1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cotter G, Metra M, Davison BA, et al. Systolic blood pressure reduction during the first 24 h in acute heart failure admission: friend or foe? European journal of heart failure 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dupont M, Mullens W, Finucan M, et al. Determinants of dynamic changes in serum creatinine in acute decompensated heart failure: the importance of blood pressure reduction during treatment. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:433–40. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Voors AA, Davison BA, Felker GM, et al. Early drop in systolic blood pressure and worsening renal function in acute heart failure: renal results of Pre-RELAX-AHF. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:961–7. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsue Y, Damman K, Voors AA, et al. Time-to-furosemide treatment and mortality in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:3042–51. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levy PD, Laribi S, Mebazaa A. Vasodilators in acute heart failure: review of the latest studies. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep 2014;2:126–32. 10.1007/s40138-014-0040-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singh A, Laribi S, Teerlink JR, et al. Agents with vasodilator properties in acute heart failure. Eur Heart J 2017;38:317–25. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Follath F, Yilmaz MB, Delgado JF, et al. Clinical presentation, management and outcomes in the Acute Heart Failure Global Survey of Standard Treatment (ALARM-HF). Intensive Care Med 2011;37:619–26. 10.1007/s00134-010-2113-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nieminen MS, Brutsaert D, Dickstein K, et al. EuroHeart Failure Survey II (EHFS II): a survey on hospitalized acute heart failure patients: description of population. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2725–36. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maggioni AP, Dahlström U, Filippatos G, et al. EURObservational research programme: the heart failure pilot survey (ESC-HF Pilot). Eur J Heart Fail 2010;12:1076–84. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chioncel O, Vinereanu D, Datcu M, et al. The romanian acute heart failure syndromes (RO-AHFS) registry. Am Heart J 2011;162:142–53. 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Spinar J, Parenica J, Vitovec J, et al. Baseline characteristics and hospital mortality in the Acute Heart Failure Database (AHEAD) Main registry. Crit Care 2011;15:R291 10.1186/cc10584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Minami Y, Kajimoto K, Sato N, et al. Admission time, variability in clinical characteristics, and in-hospital outcomes in acute heart failure syndromes: findings from the ATTEND registry. Int J Cardiol 2011;153:102–5. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishihara S, Gayat E, Sato N, et al. Similar hemodynamic decongestion with vasodilators and inotropes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 35 studies on acute heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol 2016;105:971–80. 10.1007/s00392-016-1009-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alexander P, Alkhawam L, Curry J, et al. Lack of evidence for intravenous vasodilators in ED patients with acute heart failure: a systematic review. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:133–41. 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chatterjee K, De Marco T, Rouleau JL. Vasodilator therapy in chronic congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1988;62:46A–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. ter Maaten JM, Dunning AM, Valente MA, et al. Diuretic response in acute heart failure – an analysis from ASCEND-HF. Am Heart J 2015;170:313–21. 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Valente MA, Voors AA, Damman K, et al. Diuretic response in acute heart failure: clinical characteristics and prognostic significance. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1284–93. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. ter Maaten JM, Valente MA, Damman K, et al. Diuretic response in acute heart failure-pathophysiology, evaluation, and therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12:184–92. 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peacock WF, Fonarow GC, Emerman CL, et al. Impact of early initiation of intravenous therapy for acute decompensated heart failure on outcomes in ADHERE. Cardiology 2007;107:44–51. 10.1159/000093612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peacock WF, Emerman C, Costanzo MR, et al. Early vasoactive drugs improve heart failure outcomes. Congest Heart Fail 2009;15:256–64. 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2009.00112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maisel AS, Peacock WF, McMullin N, et al. Timing of immunoreactive B-type natriuretic peptide levels and treatment delay in acute decompensated heart failure: an ADHERE (Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry) analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:534–40. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wong YW, Fonarow GC, Mi X, et al. Early intravenous heart failure therapy and outcomes among older patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure: findings from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Registry Emergency Module (ADHERE-EM). Am Heart J 2013;166:349–56. 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]