Abstract

Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm (UAP) is a rare cause of delayed postpartum haemorrhage. Early diagnosis and endovascular management are effective in treating this condition. We present the case of a 36-year-old gravida 3, para 2 woman with delayed postpartum haemorrhage and endometritis following a spontaneous vaginal delivery. Ultrasound and catheter angiogram demonstrated a UAP arising from the distal aspect of the left uterine artery. Significant bleed persisted despite selective bilateral uterine artery embolisation. A repeat angiogram confirmed complete occlusion of bilateral uterine arteries, but abdominal aortogram demonstrated that the left ovarian artery was now feeding the pseudoaneurysm. A repeat embolisation procedure was performed to occlude the left ovarian artery. The patient was discharged the following day. Selective arterial embolisation is effective in the management of UAP. Persistent bleeding despite embolisation should raise the suspicion of anastomotic vascular supply and may require repeat embolisation.

Keywords: obstetrics, gynaecology and fertility; pregnancy; interventional radiology

Background

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a potentially life-threating condition that accounts for 25% of maternal deaths worldwide.1 Delayed PPH is defined as excessive vaginal bleeding occurring between 24 hours after delivery until 6 weeks post partum.2 3 Common causes of delayed PPH include retained products of conception, endometritis, subinvolution or involution of the placental bed, arteriovenous malformation and choriocarcinoma.4 5

Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm (UAP) is a rare cause of delayed PPH. Its incidence is estimated to be around 3%.6 A UAP is an extraluminal collection of blood that communicates with the main vessel through a defect in the arterial wall.7 It can mimic and mask other entities, such as adnexal masses,8 septic abortion9 or endometritis, as we have reported here. It is thought that UAP develops as a complication of vascular injury resulting from inflammation, trauma or iatrogenic procedures.10 11

Case presentation

A 36-year-old gravida 3, para 2 woman was admitted to our institution on postpartum day 9 with a delayed PPH and endometritis. She had a spontaneous vaginal delivery at term with manual removal of the placenta. Estimated blood loss at delivery was average, and she did not experience any significant bleeding during her postpartum hospital stay. She had previously undergone a manual removal of the placenta following a pregnancy termination at 18-week gestation for trisomy 18. On postpartum day 9 of this current pregnancy, she returned to hospital with increasing vaginal bleeding, subjective fevers and chills, a tender uterus, sonographic evidence of air within the endometrial cavity and a white cell count of 17.1×109/L. The diagnosis of postpartum endometritis was made, and patient was started on intravenous antibiotics.

Investigations

Ultrasound showed a 1.9×1.4×1.7 cm anechoic area within the endometrium. Colour Doppler demonstrated a swirl of colours (yin-yang sign), and spectral Doppler showed the typical ‘to and fro’ pattern consistent with UAP. This was surrounded by a heterogeneous area containing multiple air locules, suspicious for retained products/endometritis (figure 1). The patient’s haemoglobin dropped acutely from 9.3 to 7.5 g/dL in the first few hours following admission and she was deemed too unstable for the MRI that was planned to fully delineate the above-mentioned intrauterine lesion. The patient was resuscitated with intravenous fluids and emergent angiography was carried out with the intent of performing bilateral uterine artery embolisation. Selective uterine artery angiogram demonstrated a 1×1 cm pseudoaneurysm arising from the distal aspect of the left uterine artery (figure 2).

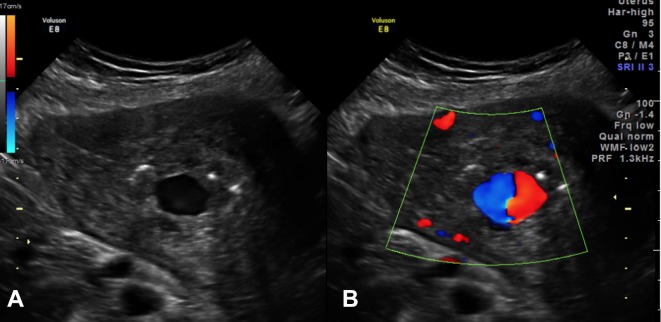

Figure 1.

(A) Transabdominal ultrasound with colour Doppler demonstrates an anechoic oval structure projecting into the uterine endometrial cavity. (B) Colour Doppler mode reveal a ‘yin-yang sign’ in keeping with an arteriovenous malformation.

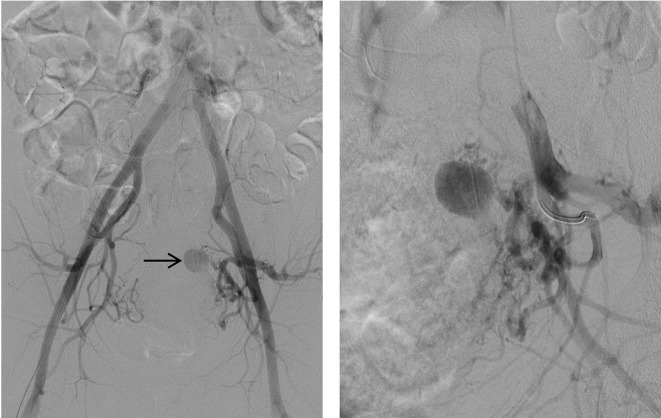

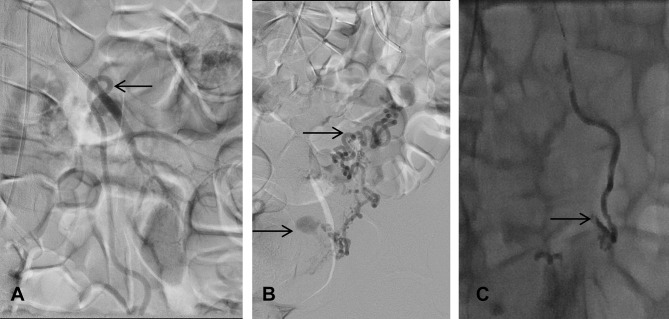

Figure 2.

Pelvic angiogram demonstrates a pseudoaneurysm (see arrow) arising from the distal branches of the left uterine artery.

Treatment

Selective bilateral uterine artery embolisation was performed using gelfoam slurry—a non-permanent embolisation material (figure 3). The patient’s blood pressure and coagulation factors were normal prior to her embolisation procedure. Although no transfusion was required, the patient continued to bleed on the day following the embolisation procedure. An MRI of pelvis with contrast was performed to assess the uterus and endometrium. This surprisingly revealed a persistently enhancing UAP, thereby suggesting recanalisation of the uterine artery (figure 4). A repeat angiogram, however, showed that both the uterine arteries were still completely occluded (figure 5). Abdominal aortogram was then performed, and it demonstrated that the left ovarian artery was now feeding the UAP and preventing its thrombosis (figure 6). Therefore, the left ovarian artery was selectively embolised; this led to a complete thrombosis of the UAP (figure 7).

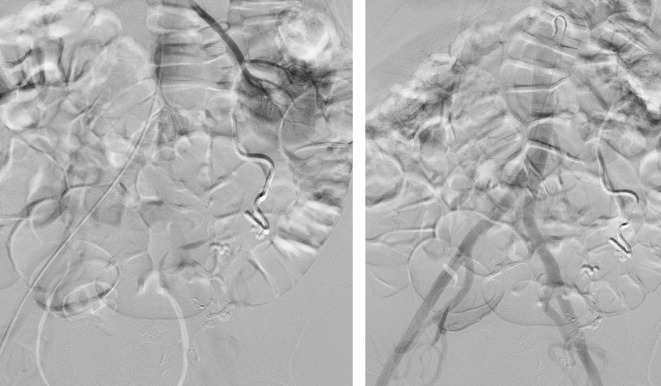

Figure 3.

Post bilateral uterine artery embolisation with gelfoam of (A) right and (B) left uterine arteries.

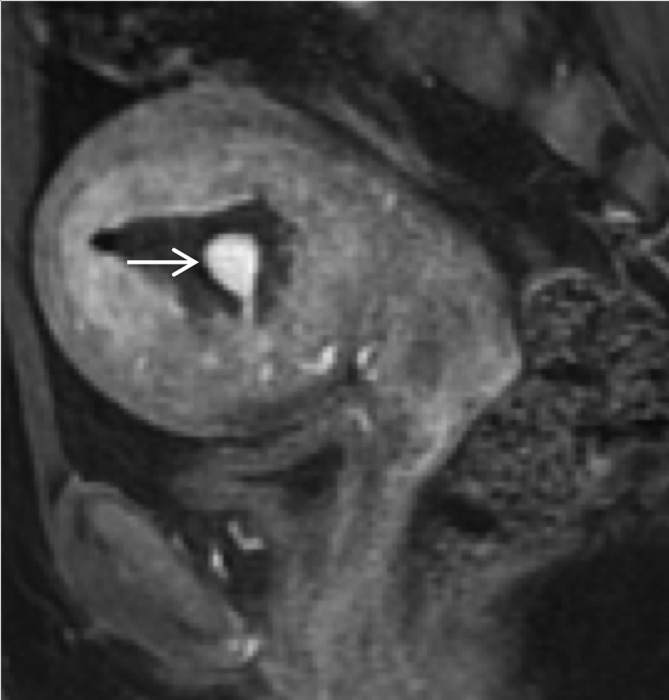

Figure 4.

Circumscribed homogenously enhancing intraluminal mass connected with a thin vascular pedicle to the spiral arteries consistent with a pseudoaneurysm that recanalised despite previous gelfoam embolisation. The arrow points to the pseudoaneurysm.

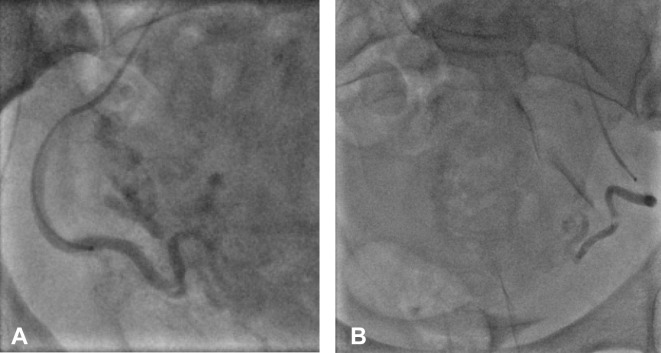

Figure 5.

Persistent occlusion of previously (24 hours prior) gelfoam embolised right (A) and left (B) uterine arteries. The previously demonstrated pseudoaneurysm is no longer identified on the left (B) on selective bilateral internal iliac angiograms.

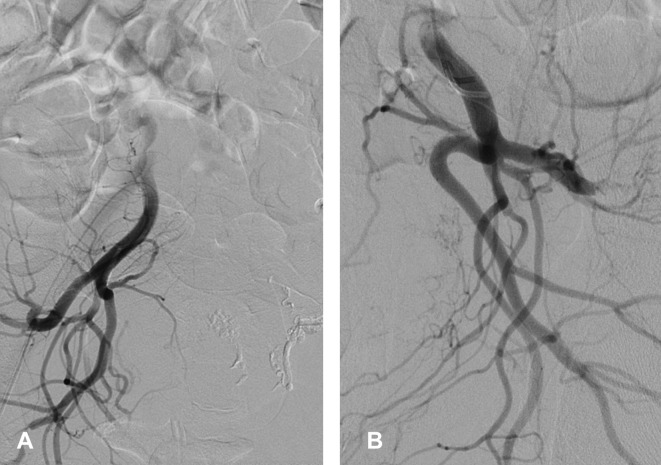

Figure 6.

Pseudoaneurysm fed by the left ovarian artery arising from the left renal artery. Pseudoaneurysm successfully embolised using glue/lipiodol (1:3). (A) Origin of the ovarian artery arising from the left renal artery. (B) Left ovarian artery feeding the pseudoaneurysm via vascular anastomosis. (C) Complete occlusion of left ovarian artery and the pseudoaneurysm. The arrows in (A) and (B) demonstrate the vessels feeding the pseudoaneurysm, whereas the arrow in (C) shows the occluded pseudoaneurysm.

Figure 7.

Left renal angiogram and abdominal aortogram demonstrate complete exclusion of the left uterine artery pseudoaneurysm.

Outcome and follow-up

Following the second embolisation procedure, the patient’s bleeding slowed substantially, and she was discharged on postprocedure day 2. She continued to have a healthy postpartum course thereafter and was well at her 6-week follow-up appointment.

Discussion

Selective arterial embolisation is an effective method for the treatment of arterial pseudoaneurysms. However, embolisation failures may still occur in the presence of an alternate feeding vessel. We report a case of UAP after vaginal delivery which required repeat embolisation due to an anastomotic feeding vessel originating from the left ovarian artery.

Brown et al first reported its use in 1979 for the treatment of an extrauterine pelvic haematoma after three failed surgical attempts to control the bleeding.12 The procedure has since been widely used for management of arterial pseudoaneurysms.13 There have been several case reports of UAP requiring embolisation during pregnancy,14 following abortions,15 traumatic deliveries or caesarean sections,10 13 cervical conisation,16 myomectomies17 and hysterectomies.18 It is thought that traumatic procedures may cause injury to the uterine artery wall, leading to extravasation of blood into periarterial tissues, thereby creating a perfused sac. This sac then communicates directly with the arterial lumen and forms a pseudoaneurysm.15 Baba et al retrospectively analysed data involving 50 women with angiographically proven UAP and suggested that all patients with an actively bleeding UAP warranted immediate embolisation.19 Arterial embolisation can be performed using gelatin sponge alone, or in addition to metallic coils or n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate.6 There is no evidence on the best type of embolisation substance to use. The choice is therefore at the discretion of the interventional radiologist. Despite potential complications of arterial embolisation including fever, ischaemia, transient to permanent ovarian failure, bladder wall necrosis, vaginal fistula, muscle pain, neurological damage and perforation of surrounding vessels, uterine artery embolisation is effective in the management of UAP and has the added advantage of preserving future fertility when compared with hysterectomy.20 Alternatives to selective arterial embolisation include expectant management,19 laparoscopic uterine artery ligation with UAP excision21 and hysterectomy for patients who have completed their family. Expectant management should be reserved for patients with no current bleeding and no sonographic evidence of any intrauterine hypoechoic mass.19 One recent case report demonstrated the feasibility of using an intrauterine balloon tamponade test for small UAPs (<13 mm) to promote thrombosis prior to dilatation and evacuation.22 But this procedure carries potential risk of UAP rupture during balloon insertion into the uterus, particularly if the UAP is projecting into the endometrial cavity, as it was in our case.

Failure of uterine artery embolisation can be multifactorial in aetiology. Potential causes include incomplete embolisation, haemodynamic instability causing arterial vasospasm, recanalisation of embolised arteries, prominent utero-ovarian anastomosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation and arterial vasodilation caused by postembolisation intravenous fluids and blood transfusion therapy.23–25 The pseudoaneurysm in our report had a dual blood supply from both the uterine artery and a branch of the ovarian artery. This was the reason for the failure of the primary embolisation procedure. Previous studies have reported that the primary site of arterial pseudoaneurysms is usually within the uterine arteries (75%), with other feeding vessels such as the ovarian, internal pudendal or obturator arteries being the exception rather than the norm.6 9 26 Generally, embolisation failures can be managed with repeat embolisation. To prevent secondary embolisations, Pelage et al recommended flush aortography with possible superselective ovarian arteriograms to assess for ovarian artery anastomoses.27 Direct speculum examination during the initial embolisation procedure is also important to allow for early detection of any active bleeders.28 A recent case report also described the use of intra-arterial nitroglycerin during embolisation for severe PPH with uterine artery vasospasm.28 Barring one case report of a UAP which sourced from an anastomotic ovarian artery, the need for ovarian arteriogram during routine embolisation procedures has rarely been discussed in the literature.19

In the present case, we report a patient who required repeated embolisation due to an anastomotic feeding vessel originating from the ovarian artery. In order to prevent similar embolisation failures, we would recommend that a direct speculum examination and an angiogram of the ovarian arteries be performed at the end of routine uterine artery embolisation procedures to allow for early detection of ongoing bleeders.

Learning points.

Selective arterial embolisation is an effective treatment for uterine artery pseudoaneurysm (UAP). However, an anastomotic feeding vessel may cause embolisation failure.

If bleeding persists following embolisation, it is important to determine if the embolised artery has recanalised, or if another anastomotic vessel is responsible.

A hidden anastomotic feeding vessel from the ovarian artery may cause unsuccessful embolisation of a UAP. An angiogram of the ovarian arteries should be performed at the end of uterine artery embolisation procedures to prevent embolisation failure.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors participated in patient care. The data collection was done by CQW. MN was involved in the analysis and interpretation of images. Literature review was performed by CQW. All authors contributed intellectual content to the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Al-Zirqi I, Vangen S, Forsen L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of severe obstetric haemorrhage. BJOG 2008;115:1265–72. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01859.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper BC, Hocking-Brown M, Sorosky JI, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the uterine artery requiring bilateral uterine artery embolization. J Perinatol 2004;24:560–2. 10.1038/sj.jp.7211119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Combs CA, Murphy EL, Laros RK. Factors associated with postpartum hemorrhage with vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol 1991;77:69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khong TY, Khong TK. Delayed postpartum hemorrhage: a morphologic study of causes and their relation to other pregnancy disorders. Obstet Gynecol 1993;82:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lausman AY, Ellis CAJ, Beecroft JR, et al. A rare etiology of delayed postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2008;30:239–43. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32760-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dohan A, Soyer P, Subhani A, et al. Postpartum hemorrhage resulting from pelvic pseudoaneurysm: a retrospective analysis of 588 consecutive cases treated by arterial embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2013;36:1247–55. 10.1007/s00270-013-0668-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chacko J, Gross S, Swischuk PN, et al. Young Woman With Vaginal Bleeding. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm. Ann Emerg Med 2016;67:e3–4. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.07.493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahana S, Biswas S. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm mimicking adnexal mass. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery 2013;29:336–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsubara S, Nakata M, Baba Y, et al. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm hidden behind septic abortion: pseudoaneurysm without preceding procedure. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2014;40:586–9. 10.1111/jog.12173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dasari P, Maurya DK, Mascarenhas M. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm: a rare cause of secondary postpartum haemorrhage following caesarean section. BMJ Case Rep 2011;2011:bcr0120113709 10.1136/bcr.01.2011.3709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeda A, Koyama K, Imoto S, et al. Early diagnosis and endovascular management of uterine artery pseudoaneurysm after laparoscopic-assisted myomectomy. Fertil Steril 2009;92:1487–91. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown BJ, Heaston DK, Poulson AM, et al. Uncontrollable postpartum bleeding: a new approach to hemostasis through angiographic arterial embolization. Obstet Gynecol 1979;54:361–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isono W, Tsutsumi R, Wada-Hiraike O, et al. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm after cesarean section: case report and literature review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2010;17:687–91. 10.1016/j.jmig.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornette J, van der Wilk E, Janssen NM, et al. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm requiring embolization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123(2 Pt 2 Suppl 2):453–6. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YA, Han YH, Jun KC, et al. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm manifesting delayed postabortal bleeding. Fertil Steril 2008;90:849.e11–4. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain J, O’Leary S, Sarosi M. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm after uterine cervical conization. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123(2 Pt 2 Suppl 2):456–8. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higón MA, Domingo S, Bauset C, et al. Hemorrhage after myomectomy resulting from pseudoaneurysm of the uterine artery. Fertil Steril 2007;87:417.e5–8. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee WK, Roche CJ, Duddalwar VA, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the uterine artery after abdominal hysterectomy: radiologic diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185:1269–72. 10.1067/mob.2001.117974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baba Y, Takahashi H, Ohkuchi A, et al. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm: its occurrence after non-traumatic events, and possibility of "without embolization" strategy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016;205:72–8. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vegas G, Illescas T, Muñoz M, et al. Selective pelvic arterial embolization in the management of obstetric hemorrhage. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2006;127:68–72. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciebiera M, Słabuszewska-Jóźwiak A, Zaręba K, et al. Management of uterine artery pseudoaneurysm: advanced ultrasonography imaging and laparoscopic surgery as an alternative method to angio-computed tomography and transarterial embolization. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2017;12:106–9. 10.5114/wiitm.2017.66503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Takagi A, Kikugawa A, et al. Use of Intrauterine Balloon Tamponade Test to Determine the Feasibility of Dilation and Evacuation as a Treatment for Early Uterine Artery Pseudoaneurysm. J Med Ultrasound 2016;24:154–8. 10.1016/j.jmu.2016.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schirf BE, Vogelzang RL, Chrisman HB. Complications of uterine fibroid embolization. Semin Intervent Radiol 2006;23:143–9. 10.1055/s-2006-941444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang BC. Treatment Failure after Uterine Artery Embolization for Symptomatic Uterine Fibroids: Significance of Ovarian Arterial Collateral Vessels in Predicting the Outcome. The Ewha Medical Journal 2012;35:102–9. 10.12771/emj.2012.35.2.102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wada N, Tachibana D, Nakagawa K, et al. Pathological findings in a case of failed uterine artery embolization for placenta previa. Jpn Clin Med 2013;4:JCM.S11317–8. 10.4137/JCM.S11317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagayama S, Matsubara S, Horie K, et al. The ovarian artery: an unusual feeding artery of uterine artery pseudoaneurysm necessitating repetitive transarterial embolisation. J Obstet Gynaecol 2015;35:656–7. 10.3109/01443615.2014.991295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelage JP, Walker WJ, Le Dref O, et al. Ovarian artery: angiographic appearance, embolization and relevance to uterine fibroid embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2003;26:227–33. 10.1007/s00270-002-1875-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Horiuchi I, Mikami Y, et al. Use of intra-arterial nitroglycerin during uterine artery embolization for severe postpartum hemorrhage with uterine artery vasospasm. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2015;54:187–90. 10.1016/j.tjog.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]