Abstract

Yellow maize kernels were subjected to supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) extraction to obtain a lutein-rich extract with potential nutraceutical properties. SC-CO2 extraction parameters (pressure and temperature) were optimized by employing a full-factorial (32) design of experiments and response surface methodology, based on yield of lutein, antioxidant activity, and ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio of the extracts. A Chrastil equation was also developed for predicting the solubility of lutein in SC-CO2 under different extraction conditions. The optimized extraction condition was obtained at 500 bar, 70 °C for 90 min, at which the extract was found to possess a unique combination of the highest lutein yield (275.00 ± 3.50 μg/g of dry weight), along with a well-balanced ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio (3:1). Moreover, the total phenol content and antioxidant activity were also found to be the highest at this condition. This lutein-rich extract is a promising nutraceutical or dietary supplement in the food industry.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10068-017-0215-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction, Yellow maize, Lutein, Antioxidant activity, ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid

Introduction

Lutein (C40H56O2), a yellow plant pigment of the xanthophyll family, is commonly used as a natural colorant in foods and feeds and as an antioxidant in nutraceuticals [1–3]. It is a therapeutically important biomolecule which is reportedly known to reduce risks of cataract, age related macular degeneration (AMD), coronary heart disease, and certain types of cancer [4, 5].

Yellow maize (Zea mays), the third most important crop after rice and wheat, owing to its widespread acceptability as a staple food in many populations [6], is considered to be one of the major dietary sources of lutein [7]. The current study endeavors to obtain a lutein-rich extract from yellow maize kernels by employing supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) extraction technology. This is a green extraction technique that exerts several advantages over the conventional techniques of solvent extraction and steam distillation. This technique is environment-friendly, the extracts are devoid of organic solvent residues, and there is minimal thermal degradation of phytochemicals during extraction. This process is therefore highly amenable to extraction of phytochemicals from natural (food) matrices [8].

It is opined that this high-pressure extraction process would most likely rupture the oil glands of maize kernels; therefore, ω-6 and ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) could possibly be co-extracted with lutein. It is known that the ratio of ω-6/ω-3 PUFAs is an important factor for human health, wherein an imbalance may lead to adverse health consequences [9]. An excessive amount of ω-6 PUFA and a very high ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio may trigger the onset of cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and inflammatory diseases; whereas increased levels of ω-3 PUFAs may exert suppressive effects on the same [10].

This study therefore focuses on the optimization of the SC-CO2 extraction parameters (temperature and pressure) using a full-factorial (32) design and response surface methodology (RSM) to obtain an extract with the best combination of phytochemical properties (yield of lutein, total phenol content, and antioxidant activity) along with a balanced ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio. This investigation also aims at determining the solubility of lutein in SC-CO2 under different temperature and pressure conditions using the Chrastil approach. The Chrastil equation would allow the prediction of lutein yield at different extraction conditions and would certainly be useful for scaling up of the SC-CO2 extraction process for this bioactive pigment.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no available literature on SC-CO2 extraction of lutein from yellow maize kernels till date. The current investigation reports for the first time on SC-CO2 extraction of lutein from yellow maize kernels of West Bengal (in East India) origin. We envisage that this lutein-rich extract could have promising usage as a nutraceutical in the food and pharmaceutical industries.

Materials and methods

Materials

Fresh yellow maize kernels (Zea mays, var: HKI 193-1F) were procured from Zonal Adaptive Research Station (ZARS), located at Krishnagar (88°33′N, 23°24′E; 13 m above sea level), West Bengal, India. The plants were grown in well-drained, deep, loamy soil (pH: 7.5–8.5) and in mild climate (18–27 °C, 60–80% relative humidity) [11].

Chemicals such as lutein (xanthophyll, X6250), 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH), and gallic acid were procured from M/s Sigma (Bengaluru, Karnataka, India), and fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) mix [butyric acid methyl ester (C4:0)−nervonic acid methyl ester (C24:1n9)] was procured from M/s Supelco Analytical (St. Louis, MO, USA). Food grade CO2 was purchased from M/s BOC India Ltd. (Kolkata, West Bengal, India), and the SPE-ED matrix for supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) vessel packing was procured from M/s Applied Separations (Allentown, PA, USA). All other chemicals were purchased from M/s E-Merck (Mumbai, Maharashtra, India). All chemicals, solvents, and buffers used in this work were of analytical reagent (AR) grade.

Preparation of powder samples from maize kernels

Maize kernels were pulverized using an electric grinder (HL 1618, M/s Philips, Kolkata, West Bengal, India), and their particle diameters were determined using the sieve analysis method. The maize samples were screened through a set of standard sieves in a sieve shaker (AS 200, M/s Retsch, Haan, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) and the mean particle diameter (d p) was determined to be 0.42 ± 0.02 mm in accordance with the method reported by Bhattacharjee et al. [12].

Optimization of SC-CO2 extraction conditions for extraction of lutein from raw maize kernels

SC-CO2 extractions were performed in a laboratory scale SCF Green Technology SPE-ED SFE 2 model (M/s Applied Separations, Allentown, PA, USA). The extraction vessel was a 50 mL SS 316 cylinder of length 304.79 mm and internal diameter 14.22 mm. The extraction process parameters such as sample batch size, particle diameter, extraction time (= static time + dynamic time), and flow rate of gaseous CO2 were fixed through several preliminary trials.

From the preliminary extractions, it was observed that a diameter (d p) greater than 0.42 ± 0.02 mm decreased the surface to volume ratio of the ground maize kernels, which decreased yield of lutein in the extracts; whereas a lower d p resulted in tight packing of the sample matrix in the extraction vessel, restricting free channeling of SC-CO2 through the sample matrix. Therefore, the particle diameter of 0.42 ± 0.02 mm was used in all extraction runs. A batch size of 35 g of ground maize powder was required to allow reliable quantification of yields of lutein in the extracts. A batch size greater than 35 g restricted loading the filler material (SPE-ED matrix) in the vessel, which is necessary to control moisture content and minimize voidage in the packed bed. Higher batch size also impeded placement of polypropylene frits and end fittings, essential for high-pressure vessels. Hence a batch size of 35 g was employed in each extraction. Moreover, preliminary trials conducted at three different extraction time (60, 90, and 150 min) established that yield of lutein (the amount of lutein extracted/recovered per 100 g mass of dried maize kernels under varying SC-CO2 extraction conditions [13]) was significantly higher at 90 min (static time: 60 min, dynamic time: 30 min, after which no extract was obtained) than those obtained at 60 and 150 min of extraction. Therefore the extraction time was kept constant at 90 min. The flow rate of gaseous CO2 (food grade) was set at 2 L/min because a flow rate above this resulted in sputtering of the extract in the wall of the collection vial and carryover of the same in the outlet tubing leading to a loss in the extract yield. Preliminary trials also suggested that significant yields of lutein with appreciable phytochemical properties of the extracts were obtained in a temperature range of 60–80 °C and a pressure zone of 400–500 bar, beyond which yields of lutein in the extracts were found to be significantly (p < 0.05) low. Hence, the upper and lower limits of extraction pressure were fixed at 500 and 400 bar, respectively; whereas for temperature, these limits were set to 80 and 60 °C, respectively.

Based on the results of preliminary trials, the SC-CO2 extraction parameters (pressure and temperature) were optimized using a 32 full-factorial design, where extraction pressure (400, 450, and 500 bar) and temperature (60, 70, and 80 °C) were varied at three levels. The extracts were collected in screw-capped collection vials (previously wrapped in Al foil) and placed in an ice bath in the dark. They were subsequently weighed, dissolved in high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade dichloromethane (DCM), and stored in nitrogen flushed screw-capped amber colored glass vials at 4 °C until further analyses.

Solvent extraction of lutein from yellow maize kernels was also performed using the classical Soxhlet extraction assembly with 5 g ground, sieved maize kernels (d p = 0.42 ± 0.02 mm) to quantify the amount of lutein present. The extraction was conducted for 8 h using n-hexane as the extracting solvent, in accordance with AOAC official method 920.39A [14]. The extract was then concentrated using a rotary vacuum evaporator (M/s Eyela Corp., Tokyo, Japan) at 40–45 °C and 50 mbar and stored under conditions similar to those mentioned above.

Quantification of lutein in SC-CO2 and solvent extracts of maize kernels

Lutein-rich extracts (SC-CO2 and solvent extracts) were subjected to HPLC analyses for quantification of lutein contents, in accordance with the method described by Bhattacharyya et al. [15].

20 μL of lutein-rich extracts (dissolved in DCM) was injected into a JASCO HPLC system, which was equipped with an LC-NET (LC-NET-2/ADC), an isocratic pump (PU-2080 Plus), a degasser (DG-2080-54), and a detector (MD-2015 Plus). A C18 reversed phase column (l = 250 mm and i.d. = 4.6 mm) was used for the separation of lutein from the mixture of compounds present in the extracts, and the flow rate of the mobile phase [acetonitrile/methanol/ethyl acetate (9:1:2)] was maintained at 1 mL/min. The eluents were continuously monitored in a photo diode array (PDA) detector at 447 nm. Identification of peak of lutein was based on its retention time in comparison with standard lutein (M/s Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Evaluation of phytochemical properties of SC-CO2 extracts of maize kernels

Antioxidant activities of the extracts were determined by assaying the radical scavenging activities of DPPH [16], and expressed as IC50 values (mg/mL), and also by ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay, and expressed as mM FeSO4 equivalent/g dry weight (DW) [17]. The total phenolic content in the extracts was also estimated using Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent [18] and was expressed as μg gallic acid equivalent (GAE)/g D.W. The total phenolic content and FRAP values were determined from their respective standard curves of gallic acid and ferrous sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O).

Analysis of the morphology of yellow maize grit matrix using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM)

To fully understand the mechanism of SC-CO2 extraction of lutein from the matrix of yellow maize kernels, the microstructure of the unprocessed and SC-CO2 processed sample matrices were subjected to microscopic studies by FE SEM. The samples were coated with platinum using an Autofine Coater (JFC-1600, JEOL Company Ltd., Japan) and analyzed using a FESEM (JSM-6700F, JEOL Company Ltd., Japan) operated at 5 kV with a working distance of 8 mm.

Analysis of fatty acid composition of maize grit extracts

Samples of FAME derivatives of fatty acids were prepared using SC-CO2 extracts of maize kernels at different extraction conditions, in accordance with the method described by Kaushik and Agnihotri [19]. A gas chromatograph (GC) (Trace GC 700, M/s Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) attached to TR-1 capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm, i.d. 0.25 μm) and equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) was used to determine the fatty acid profile of the individual FAME sample. The carrier gas used was N2 at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The injector and detector temperatures were 250 and 260 °C, respectively. The oven temperature was increased from 60 °C (2 min hold with an increasing rate of 10 °C/min) to 200 °C (with an increasing rate of 3 °C/min) and further increased to 260 °C (8 min hold). 1 μL of each FAME sample (dissolved in n-hexane) was injected into the GC injector port in split-less mode for analyses. Identification of fatty acids was conducted using the standard 37-component FAME mix [butyric acid methyl ester (C4:0)−nervonic acid methyl ester (C24:1n9)] of M/s Supelco Analytical (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Determination of solubility of lutein in SC-CO2 using Chrastil equation

Determination of solubility of lutein in SC-CO2 at different extracting pressure–temperature conditions is crucial for validation of varying lutein yields, and therefore for the optimization of the extraction process. The solubilities of lutein were evaluated under varying extraction conditions in accordance with the method of Chatterjee and Bhattacharjee [20]. The solubility was expressed as the ratio of the total mass of extracted lutein (g) and the mass of carbon dioxide consumed in the extraction process:

| 1 |

where Y is the solubility (mass fraction) of lutein in SC-CO2 extracts, Mo is the total mass of lutein recovered (g) in the total amount of the extract, V is the volume of carbon dioxide (mL) used for extraction, and ρ is the density of SC-CO2 (kg/m3) under different extraction conditions. The densities of SC-CO2 under different conditions (temperature and pressure) were calculated using the empirical Peng–Robinson cubic equation of state [21] in accordance with the method reported by Bhattacharjee et al. [12].

In order to correlate the solubility data of solids and liquids in dense gases, Chrastil equation which gives a linear relationship between the logarithm of solubility of a solute and the logarithm of SC-CO2 density has been used by several researchers [22–24]. The Chrastil equation [23, 24] of Catchpole and Von-Kamp [25], is as follows:

| 2 |

where S is the solubility of lutein in the gas phase (g/kg), k is the association constant related to the total number of molecules in the complex [26], ρ is the density of CO2 (kg/m3), F and G are empirical constants in density correlation, and T is the temperature (K).

The values of k, F, and G of Eq. (2) were determined and a linear equation was developed which allowed the prediction of solubility of lutein in SC-CO2 under varying extraction conditions [20].

Statistical analyses

All experiments were performed in triplicate and the data were expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experimental runs. One-way ANOVA was performed to study the effects of extraction parameters (pressure and temperature) on the response variables i.e., yield of lutein, DPPH radical scavenging activity, FRAP, and ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio of the extracts. Significant differences between means were determined by Duncan’s multiple-range test, using p values ≤ 0.05. RSM and regression modeling were performed to explore the relation among the explanatory variables (pressure and temperature) and the four different response variables mentioned above. STATISTICA 8.0 software (Statsoft, Oklahoma, USA) was used to test the experimental results.

Results and discussion

Optimization of SC-CO2 extraction parameters using RSM

Fitting the model

Table 1 represents lutein yields of SC-CO2 extracts of maize kernels under different extraction conditions. The maximum lutein yield (275 ± 4.65 μg/100 g D.W.) was obtained at 500 bar, 70 °C after 90 min of extraction. This could be due to the maximum solubility of lutein at this extraction condition (discussed later). This extract also showed maximum phytochemical potency in terms of highest phenol content, minimum IC50 value, and maximum FRAP value, along with a well-balanced ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio (Table 1).

Table 1.

Experimental yields of SC-CO2 extracts of maize kernels, yields of lutein and phytochemical properties of the extracts

| Pressure (bar) | Temperature (°C) | Yields of maize grit extract (mg/g dry maize grits)1 | Yields of lutein (μg/100 g dry maize grits)1 | Total phenolic contents (μg gallic acid equivalent/g dry maize grits)1 | IC50 values of DPPH radical scavenging activities (mg/mL)1 | FRAP values (mM FeSO4 equivalent/g dry maize grits)1 | ω-6:ω-3 PUFAs1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400 | 60 | 17.16 ± 0.53a | 77 ± 2.13a | 0.81 ± 0.02a | 9.34 ± 0.58a | 130 ± 1.25a | 1.57 |

| 400 | 70 | 28.33 ± 1.78b | 138 ± 3.65b | 2.05 ± 0.12e | 7.56 ± 0.39b | 232 ± 2.74b | 0.20 |

| 400 | 80 | 70.33 ± 1.74c | 153 ± 3.74c | 0.92 ± 0.06d | 7.12 ± 0.45c | 252 ± 3.87c | 0.09 |

| 450 | 60 | 78.34 ± 1.34cd | 179 ± 4.17d | 1.72 ± 0.03a | 6.35 ± 0.31d | 278 ± 2.19d | 9.83 |

| 450 | 70 | 91.43 ± 1.19d | 218 ± 3.49e | 2.00 ± 0.05e | 5.12 ± 0.29e | 300 ± 2.65e | 2.89 |

| 450 | 80 | 135.2 ± 2.17f | 239 ± 2.97f | 1.12 ± 0.04b | 4.89 ± 0.33f | 320 ± 5.48f | 0.16 |

| 500 | 60 | 105.5 ± 3.59e | 253 ± 2.11g | 1.23 ± 0.07b | 4.51 ± 0.26g | 375 ± 4.38g | 28.65 |

| 500 | 70 | 112.56 ± 2.02ef | 275 ± 4.65h | 2.55 ± 0.14f | 3.85 ± 0.17h | 402 ± 3.99h | 3.00 |

| 500 | 80 | 156 ± 2.76g | 207 ± 3.29i | 1.42 ± 0.05c | 5.96 ± 0.41i | 289 ± 4.28i | 0.63 |

1 Yields of maize grit extracts, yields of lutein and total phenol contents, IC50 values of of DPPH radical scavenging activities, and FRAP values of maize seed extracts are mean ± SD of three independent extraction runs of three batches of yellow maize kernels

Different letters within a column indicate significant differences at p < 0.05

From the ANOVA tables of regression models, it was established that yields of lutein (Table 2), and FRAP values (ANOVA tables) increased significantly (p = 0.000), and IC50 values decreased significantly (p = 0.001) with the increase in extraction temperature (in linear terms) from 60 to 80 °C, at constant pressure (400, 450, and 500 bar); and with increasing extraction pressure from 400 to 500 bar, at constant temperature (60, 70, and 80 °C). Similar results of significantly enhanced yields of lutein (p < 0.05) with increasing pressure (350–450 bar) and temperature (from 70 to 80 °C) were also obtained in our previous investigation on SC-CO2 extraction of lutein from African marigold flowers [27]. In another study, Ma et al. [28] reported that pressure and temperature in their linear and quadratic forms had significant effects on yield of lutein extracted from marigold flowers.

Table 2.

ANOVA study to investigate the effect of extraction parameters (pressure and temperature) on yields of lutein of the extracts

| Effect | Degree of freedom | Yields of lutein (μg/100 g) of dried maize grits SS | Yields of lutein (μg/100 g) of dried maize grits MS | Yields of lutein (μg/100 g) of dried maize grits F | Yields of lutein (μg/100 g) of dried maize grits Pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xa1 | 1 | 67,344.50 | 67,344.50 | 420.86 | 0.000000 |

| X21 | 1 | 4760.17 | 4760.17 | 29.74 | 0.000021 |

| Xb2 | 1 | 4050.00 | 4050.00 | 25.31 | 0.000056 |

| X22 | 1 | 3952.67 | 3952.67 | 24.70 | 0.000064 |

| X1X2 | 1 | 11,163.00 | 11,163.00 | 69.76 | 0.000000 |

| Error | 21 | 3360.33 | 160.02 | – | – |

| Total | 26 | 94,630.67 | – | – | – |

aX1-exraction temperature

bX2-exraction pressure

cSignificant at p < 0.05

Moreover, the ratio of ω-6/ω-3 fatty acids was also found to increase significantly (p = 0.000) with increasing pressure under isothermal conditions; however under isobaric conditions, an opposite trend of significant (p = 0.000) decrease in the ratio was observed with increasing temperature (ANOVA tables).

Thus pressure and temperature in their linear and quadratic forms had significant effects on the yields of lutein and on antioxidant activities of the extracts; while pressure in its linear and quadratic forms and temperature in its linear forms significantly affected ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio of the extracts.

Estimation of lutein content in the solvent extract of maize

The amount of lutein obtained by the Soxhlet extraction process was found to be 168.35 ± 3.22 μg/100 g dry maize kernels. This value was significantly (p < 0.05) lower than the maximum value of lutein (Table 1) obtained by the SC-CO2 extraction process, indicating the superiority of the latter in selective extraction of lutein from yellow maize kernels.

Generation of response curves

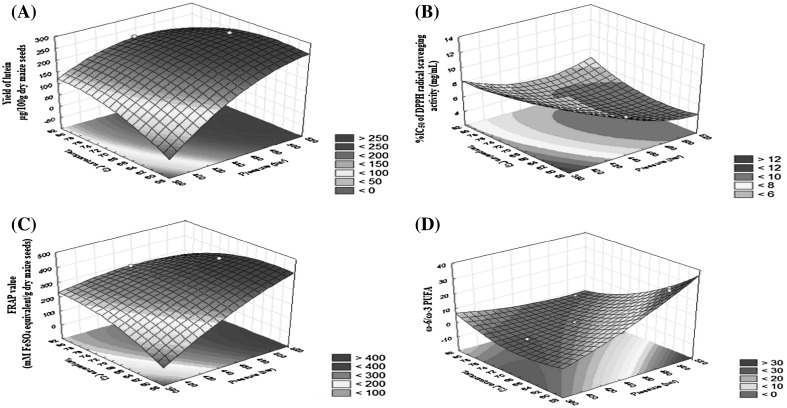

The effects of extraction pressure and temperature on lutein yield, IC50 values, FRAP values, and the ratio of ω-6/ω-3 PUFAs are shown in Fig. 1(A–D), respectively. Regression modeling was used to characterize the response surfaces.

Fig. 1.

Plots of response surfaces indicating (A) yields of lutein; (B) IC50 values of DPPH radical scavenging activity; (C) FRAP values and (D) ratios of ω-6/ω-3 fatty acids; as functions of extraction pressure (400, 450, and 500 bar) and temperature (60, 70, and 80 °C) after 90 min of extraction at a flow rate of 2 L/min with 35 g batch size

Regression modeling

Regression modeling was conducted by generating a second-order polynomial equation for each response as a function of extraction temperature and pressure. The second-order polynomial equation that fitted our experimental variables is stated below.

| 3 |

where Y represents the experimental responses [yield of lutein (Eq. 4), IC50 value (Eq. 5), FRAP value (Eq. 6), and ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio (Eq. 7)]. B0, Bi, Bii, and Bij are constants and regression coefficients of the model; Xi and Xj are two independent variables in coded forms. The expanded model includes linear, quadratic, and cross-product terms as shown below (with intercept):

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

where X1 and X2 denote the extraction pressure and temperature, respectively. These equations explain the effect of the two variables, i.e., pressure and temperature on the response Y.

The implication of the above-mentioned extraction parameters and their interactions were investigated. From the ANOVA tables, it was observed that yields of lutein (p = 0.000 for X1 and X2); IC50 values (p = 0.000 for X1 and X2), FRAP values (p = 0.000 for X1 and p = 0.002 for X2), and ratios of ω-6/ω-3 fatty acids (p = 0.000 for X1 and X2) are significantly dependent on linear terms (X1 and X2) of both extraction pressure and temperature. All the second-order terms of pressure (X21) and temperature (X22) also showed significant (p = 0.000) effects on lutein yields, IC50 and FRAP values; only temperature had a significant (p = 0.000) effect in its quadratic form on ω-6/ω-3 ratio. Further, pressure and temperature in combination showed significant (p = 0.000) effects on all four responses, i.e., yield of lutein, IC50 value, FRAP value, and ratio of ω-6/ω-3 PUFAs of the extracts.

ANOVA of each of the four models showed good F values (Fisher’s variance ratio) (Table 2 for yield of lutein, for other parameters data not shown) indicating significant interactions among the variables. The plots of observed values against the predicted values for yield of lutein, IC50 value, FRAP value, and ω-6/ω-3 PUFAs ratio showed a close fit in each case (ANOVA tables). Thus a statistically significant multiple regression relationship (r = 0.982 for yields of lutein, r = 0.985 for IC50 values, r = 0.982 for FRAP, and r = 0.958 for ω-6/ω-3 PUFAs) among the independent variables and the responding variables could be established. The complete quadratic model showed a very good fit.

Analysis of response surfaces

The response surfaces are shown in the stereoscopic figures (Fig. 1 A–D). From the test statistics for the regression models as discussed above, it was observed that the extraction pressure and temperature had significant effects on the yields of lutein, IC50 values, FRAP values, and ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio of SC-CO2 extracts of yellow maize.

Optimal processing condition

For optimization of the SC-CO2 process conditions, i.e., to determine the optimal values of X1 and X2, the first partial derivatives of the regression equation was conducted with respect to X1 and X2 and set to zero. This was done by putting the second-order regression equation into the matrix form [29, 30]. The point thus obtained is known as the stationary point, XS (X1S = 518.37 bar, X2S = 67.79 °C; obtained from the model of yield of lutein). The predicted values of yield of lutein, IC50 value, FRAP value, and ω-6/ω-3 fatty acid ratio of the extract at this stationary point were found to be 267.03 μg/g of dry maize kernels, 4.11 mg/mL, 380.22 mM FeSO4 equivalent/g D.W. of maize kernels and 1.5:1.0 respectively (ANOVA tables), suggesting a close fit of the model.

Characterization of response surfaces

The eigen values [29] obtained in the case of yield of lutein (− 0.007533 and − 0.260401) and the FRAP values of the extracts (− 0.000481 and − 0.380586) were negative because the XS of each of these models was a point of maxima. The eigen values for IC50 values were 0.008613 and 0.000273. Since these values were positive, XS was a point of minima. However, for ω-6/ω-3 fatty acids ratios, XS was found to be a saddle point with eigen values of 0.048502 and − 0.000353.

The extraction condition of 500 bar, 70 °C, and 90 min, closest to the stationary point (discussed in section ‘optimal processing condition’ under Results and discussion) was considered to be the optimized extraction condition because at this condition, the extract was found to have the best combination of highest yield of lutein, maximum antioxidant activity, and a balanced ratio of ω-6/ω-3 PUFAs.

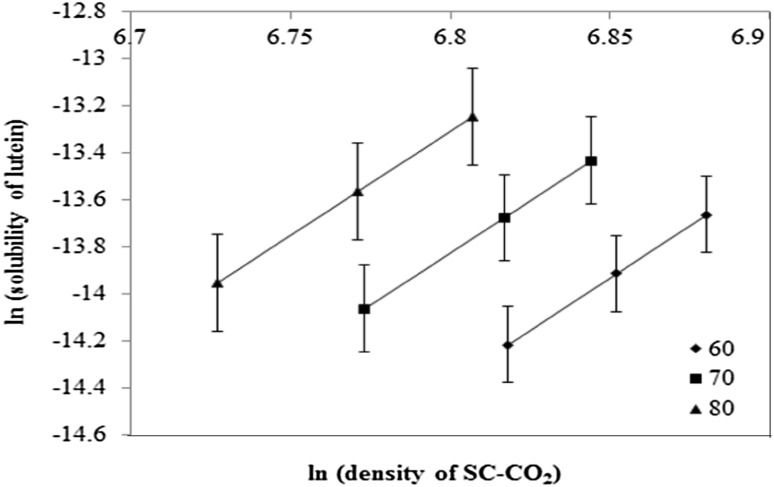

Determination of solubility of lutein in SC-CO2 using the Chrastil equation

The solubilities of lutein in SC-CO2 in this current study was found to increase significantly with elevation of temperature from 60 to 70 °C in the high-pressure range (400–500 bar) (Fig. 2). A similar finding of enhanced solute concentration with enhanced temperature during SC-CO2 extraction of lutein from spearmint has been reported by Prieto et al. [31]. However, the temperature regime (40–60 °C) and the sample matrix investigated in their study are markedly different from those of the current investigation.

Fig. 2.

Solubilities of lutein in SC-CO2, predicted by the Chrastil equation as a function of solvent densities

From the values of the solubility of lutein in SC-CO2, a linear regression equation was also developed according to the Chrastil equation. The equation generated was as follows:

| 8 |

The regression coefficient r obtained using this equation was 0.81, and the standard error of the equation was 0.25. From this Chrastil equation, the logarithm of the calculated solubility was plotted against logarithm of SC-CO2 density [20] and presented in Fig. 2. It was found that the plots were linear and the isotherms at 60, 70, and 80 °C were parallel to each other, which confirmed the suitability of the Chrastil equation in this work. The solubility values of lutein calculated at 60, 70, and 80 °C were in fair agreement with the corresponding solubility values predicted by the Chrastil equation, only with an exception at 500 bar, 80 °C; where the experimental solubility of lutein was found to be significantly (p<0.05) lower than that at 500 bar, 70 °C. It could be attributed to the fact that at high pressure (500 bar), temperature higher than 70 °C could have possibly led to co-extraction of waxy materials, impeding extraction of lutein, thereby lowering yields of lutein in the extracts.

Therefore, Eq. (8) can certainly be used to predict the solubility of lutein in SC-CO2 under different extraction conditions up to 70 °C. This equation clearly stated that the solubility of lutein in SC-CO2 was the maximum (2.87 × 10−6 g/kg CO2) under the optimized extraction condition (500 bar, 70 °C, and 90 min).

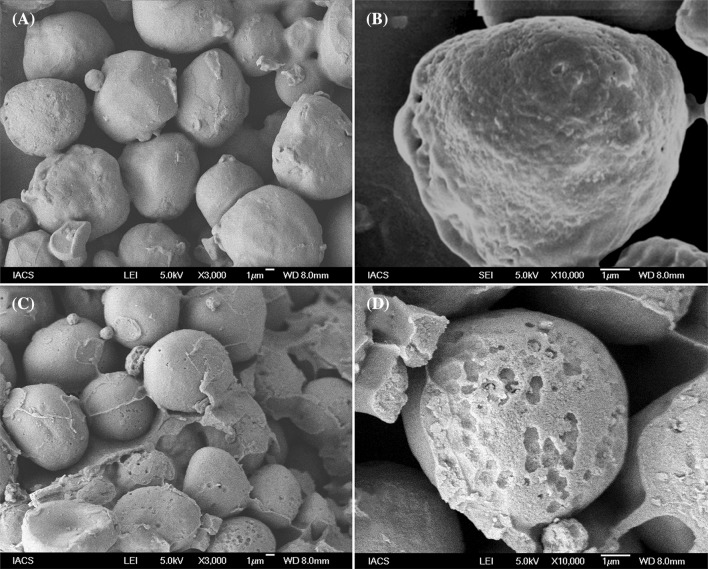

Evaluation of morphology of maize grit matrix by FE SEM analyses

Figure 3 shows the micrographs obtained using FE SEM of the sample matrices before extraction (Fig. 3A, B) and those of samples post extraction (Fig. 3C, D). In the unprocessed sample matrix, i.e., prior to extraction, it could be observed that the surface pores of the maize grit matrix were closed, whereas in the SC-CO2 processed sample, the grit tissues were found to be cracked revealing open pores at the kernel surface, which could be due to the rupture of oil bearing glands of the kernels under high pressure–temperature conditions. These morphological changes of the maize kernel matrices would have resulted in the release of oil (along with lutein) from the damaged cells. The oil then diffuses out onto the surface of the maize kernel particles and forms a film that eventually solubilizes into the bulk phase of SC-CO2, thus rendering the extracts oily in nature. This phenomenon has also been reported by Ghosh and Bhattacharjee [32] in their study on SC-CO2 extraction of methyl eugenol from tuberose flowers.

Fig. 3.

Field emission scanning electron micrographs of ground and sieved maize kernel powder matrices: (A, B) pre-extraction matrix and (C, D) post-extraction matrix; at magnifications of 3000× and 10,000×

Phytochemical analyses of the SC-CO2 extracts of maize

Analyses of phytochemical properties such as total phenolic contents, DPPH radical scavenging activities, and FRAP values of the lutein-rich SC-CO2 extracts are presented in Table 1. The highest amount of lutein was obtained in the extract at 500 bar, 70 °C, and 90 min. This extract also possessed the highest amount of phenolic compounds, along with maximum FRAP value and minimum IC50 value. This possibly established the fact that maximum co-extraction of phenolic compounds also occurred at 500 bar, 70 °C, and 90 min; and thus a strong correlation was found between these bioactive components and the antioxidant activity of the extract, as indicated by the IC50 and FRAP values.

Fatty acid composition of SC-CO2 extracts of yellow maize kernels

The complete fatty acid profiles of lutein-rich SC-CO2 extracts at nine different extraction conditions are shown in Table 3. These data revealed that the SC-CO2 extract at optimized condition (based on yield of lutein and phytochemical properties), i.e., at 500 bar, 70 °C, and 90 min also had a well-balanced fatty acid profile- 35.38% saturated fatty acid (SFA), 6.89% monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA), 55.35% polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA), and a desirable ratio of ω-6/ω-3 PUFAs (3:1), which is within the optimal range of 1:1–4:1. This range is reportedly known to reduce the risks of several chronic diseases (Simopoulos and Cleland [33]). Besides the above extract, two other extracts obtained at 400 bar, 60 °C, 90 min and 450 bar, 70 °C, and 90 min extraction conditions also possessed desirable ω-6/ω-3 fatty acids ratio, although yields of lutein and antioxidant activities of these extracts were significantly (p < 0.05) lower than those obtained at 500 bar, 70 °C, and 90 min (Table 1).

Table 3.

Fatty acid (g/100 g of fatty acids) contents in lutein-rich SC-CO2 extracts of yellow maize kernels at different extraction conditions

| Fatty acid carbon no. | Name of fatty acids | 400 bar, 60 °C | 400 bar, 70 °C | 400 bar, 80 °C | 450 bar, 60 °C | 450 bar, 70 °C | 450 bar, 80 °C | 500 bar, 60 °C | 500 bar, 70 °C | 500 bar, 80 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C6:0 | Caproic acid | – | – | – | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 7.0 ± 0.37 | 1.37 ± 0.05 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | – | – |

| C8:0 | Caprylic acid | – | 4.00 ± 0.29 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| C10:0 | Capric acid | 2.48 ± 0.16 | – | – | 0.07 ± 0.00 | – | – | – | 0.44 ± 0.01 | – |

| C11:0 | Undecanoic acid | 0.20 ± 0.14 | 0.6 ± 0.04 | – | – | – | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | – |

| C12:0 | Lauric acid | – | 0.4 ± 0.02 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| C13:0 | Tridecanoic acid | 2.76 ± 0.17 | 5.0 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 1.67 ± 0.08 | 0.69 ± 0.04 | 0.96 ± 0.07 | – | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.5 ± 0.02 |

| C14:1 | Myristoleic acid | 0.17 ± 0.00 | – | 0.16 ± 0.00 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.00 | – | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| C15:0 | Pentadeca-noic acid | – | – | – | 0.06 ± 0.00 | – | 0.07 ± 0.00 | – | – | – |

| C15:1 | Pentadece-noic acid | – | 0.08 ± 0.00 | – | – | – | 0.16 ± 0.01 | – | – | – |

| C16:0 | Palmiti-c acid | – | – | – | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 1.41 ± 0.07 | 0.17 ± 0.00 | – | 1.96 ± 0.06 | – |

| C16:1 | Palmitoleic acid | 4.37 ± 0.31 | 3.00 ± 0.18 | 8.24 ± 0.47 | 2.82 ± 0.13 | 3.13 ± 0.27 | 4.32 ± 0.29 | 1.0 ± 0.07 | – | 3.5 ± 0.15 |

| C17:0 | Hepladecanoic acid | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.55 ± 0.04 | – | 0.82 ± 0.05 | 0.26 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.45 ± 0.02 |

| C17:1 | Heptadecenoic acid | 0.21 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | – | 0.11 ± 0.00 | – | 0.18 ± 0.00 | – | – | – |

| C18:0 | Stearic acid | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | – |

| C18:1 N9c | Oleic acid | 2.75 ± 0.12 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 1.56 ± 0.10 | 1.57 ± 0.08 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | – | 1.00 ± 0.08 | – | 0.9 ± 0.05 |

| C18:1 N9t | Elaidic acid | – | 1.00 ± 0.07 | 4.48 ± 0.31 | – | – | 0.18 ± 0.00 | – | 0.98 ± 0.06 | – |

| C18:2 N6 | Linoleic acid | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 2.05 ± 0.00 | 1.31 ± 0.04 | 0.84 ± 0.05 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 2.45 ± 0.14 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.55 ± 0.02 |

| C18:3 N6 | γ-Linolenic acid | – | – | – | – | – | 0.15 ± 0.00 | 31.36 ± 1.28 | – | – |

| C20:0 | Arachidic acid | – | – | – | – | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | – | – | – |

| C20:1 N9 | Cis-11-Ei coseno-ic acid | 0.61 ± 0.03 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 1.56 ± 0.14 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 1.11 ± 0.07 | 1.12 ± 0.05 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.30 ± 0.01 |

| C20:2 | Eicosadienoic acid | – | – | 19.51 ± 1.27 | 17.00 ±1.24 | – | 13.6 ± 1.17 | – | – | 20.00 ± 1.59 |

| C20:3 N6 | Eicosatrien-oic acid | 23.36 ± 2.11 | 20.3 ± 1.58 | 8.28 ± 0.48 | 3.31 ± 0.25 | 24.5 ± 2.16 | 3.00 ± 0.24 | – | 41.43 ± 2.63 | 5.00 ± 0.44 |

| C20:3 N3 | Eicosatrien-oic acid | 3.47 ± 0.27 | – | – | 2.36 ± 0.18 | 5.56 ± 0.38 | 4.47 ± 0.37 | – | 8.78 ± 0.39 | 4.5 ± 0.37 |

| C20:4 N6 | Arachidonic acid | – | 5.12 ± 0.47 | – | 2.26 ± 0.14 | – | 1.00 ± 0.04 | – | – | – |

| C20:5 | Eicosapent-aenoic acid | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 10.3 ± 1.01 | 1.17 ± 0.06 | – | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 3.58 ± 2.15 | 1.18 ± 1.06 | 3.64 ± 0.22 | – |

| C21:0 | Henicosanoic acid | 33.05 ± 2.53 | 30.00 ± 1.99 | 16.56 ± 1.22 | 35 ± 2.28 | 30.00 ± 2.53 | 28.05 ± 2.29 | 25.00 ± 1.94 | 25.22 ± 1.66 | 41.64 ± 2.64 |

| C22:0 | Behenic acid | 5.17 ± 0.41 | 12.00 ± 1.16 | 6.37 ± 0.04 | 5.00 ± 0.38 | 6.82 ± 0.57 | 2.66 ± 0.14 | 5.00 ± 0.38 | 7.53 ± 0.05 | 3.2 ± 0.26 |

| C22:1N9 | Erucic acid | 14.54 ± 1.19 | – | 17.33 ± .132 | 3.00 ± 0.18 | 11.01 ± 1.00 | 8.74 ± 0.68 | 20.00 ± 1.43 | 5.44 ± 0.65 | 10 ± 0.78 |

| C22:2 | Docosadienoic acid | 3.43 ± 0.21 | – | 8.33 ± 0.53 | – | 1.46 ± 0.05 | 7.7 ± 0.53 | 10.00 ± 0.76 | 1.38 ± 0.11 | 2.00 ± 0.08 |

| C22:6 | Docosahexa enoic acid | – | – | 4.85 ± 0.38 | 22.11 ± 2.08 | 2.0 ± 0.16 | 20.06 ± 2.01 | – | 1.41 ± 0.10 | 4.3 ± 0.23 |

| - | Other fatty acids | 0.70 | 0.51 | 1.01 | 3.51 | 1.69 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 2.36 | 3.15 |

| - | SFA | 43.88 | 52.2 | 23.73 | 40.05 | 47.13 | 33.79 | 31.5 | 35.38 | 45.79 |

| - | MUFA | 19.26 | 4.57 | 31.78 | 7.99 | 16.46 | 11.90 | 23 | 6.89 | 14.71 |

| - | PUFA | 36.15 | 42.72 | 43.46 | 48.45 | 34.77 | 53.90 | 44.99 | 55.35 | 36.35 |

| - | ω-6/ω-3 ratio | 1.57 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 9.83 | 2.89 | 0.16 | 28.65 | 3.00 | 0.63 |

Data are mean ± SD of three independent experimental runs

SFA saturated fatty acids, MUFA monounsaturated fatty acids, PUFA polyunsaturated fatty acids

Therefore, SC-CO2 extraction condition at 500 bar, 70 °C, and 90 min is the best condition for the extraction of lutein-rich therapeutic fraction from yellow maize kernels.

Lutein content of this extract was also higher than the conventional solvent extract, attesting the superiority of SFE in selective extraction. A correlated Chrastil equation developed on the solubility of lutein in SC-CO2 under different extraction conditions further validated the highest yield of lutein at the said condition. This extract also possessed a desirable fatty acid profile with a balanced ω-6/ω-3 ratio of 3:1. We envisage that this lutein-rich extract could have potential applications in food and pharmaceutical industries.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank University Grants Commission (UGC) New Delhi, India [Ref. No: 1440/(NET-JUNE 2013)] for their financial support for this study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Moreau RA, Johnston DB, Hicks KB. Comparison of the levels of lutein and zeaxanthin in corn germ oil, corn fiber oil and corn kernel oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2007;84:1039–1044. doi: 10.1007/s11746-007-1137-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharyya S, Datta S, Mallick B, Dhar P, Ghosh S. Lutein content and in vitro antioxidant activity of different cultivars of Indian marigold flower (Tagetes patula L.) extract. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:8259–8264. doi: 10.1021/jf101262e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel-Aal ESM, Akhtar H, Zaheer K, Ali R. Dietary sources of lutein and zeaxanthin carotenoids and their role in eye health. Nutrients. 2013;5:1169–1185. doi: 10.3390/nu5041169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma L, Lin XM. Effects of lutein and zeaxanthin on aspects of eye health. J. Sci. Food Agr. 2010;90:2–12. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhnen S, Lemosa PMM, Campestrinia LH, Ogliaria JB, Diasb PF, Maraschina M. Antiangiogenic properties of carotenoids: A potential role of maize as functional food. J. Funct. Foods. 2009;1:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2009.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paraginski RT, Vanier NL, Berrios JDJ, Oliveira MD, Elias MC. Physicochemical and pasting properties of maize as affected by storage temperature. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2014;59:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2014.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sommerburg O, Keunen JEE, Bird AC, Kuijk FJGM. Fruits and vegetables that are sources for lutein and zeaxanthin: the macular pigment in human eyes. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1998;82:907–910. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.8.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukhopadhyay M (ed). Fundamentals of supercritical fluids and phase equilibria. pp 13–39. In: Natural extracts using supercritical carbon dioxide, CRC press, Florida, USA, (2000).

- 9.Sen DP. Fats and oils in health and nutrition. pp 19–23. In: Oil Technology Association of India, News Letters, Eastern region, (2011–12). Available from: http://www.otai.org/newsLetter/ez/newsLetter_Ez_Nov%202011_June_2012.pdf Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 10.Simopoulos AP. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2002;56:365–379. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(02)00253-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Annual Report (2014–15), Zonal Adaptive Research Station, Government of West Bengal, Directorate of Agriculture.

- 12.Bhattacharjee P, Chatterjee D, Singhal RS. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of squalene from Amaranthus paniculatus: experiments and process characterization. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012;5:2506–2521. doi: 10.1007/s11947-011-0612-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goto M, Sato M, Hirose T. Extraction of peppermint oil by supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1993;26:401–407. doi: 10.1252/jcej.26.401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AOAC. Official Method of Analysis of AOAC Intl. 21st ed. Method 920.39A. Association of official analytical chemists, Gaithersburg, MD (2006).

- 15.Bhattacharyya S, Datta S, Mallick B, Dhar P, Ghosh S. Lutein content and in vitro antioxidant activity of different cultivars of Indian marigold flower (Tagetes patula L.) extract. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:8259–8264. doi: 10.1021/jf101262e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spanos GA, Wrolstad RE. Influence of processing and storage on the phenolic composition of Thompson seedless grape juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1990;38:1565–1571. doi: 10.1021/jf00097a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benzie FF, Strain JJ. Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay: Direct measure of total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous measurement of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid concentration. Method Enzymol. 1999;299:15–23. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aiyegoro OA, Okoh AI. Preliminary phytochemical screening and in vitro antioxidant activities of the extract of Helichrysum longifolium DC. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2010;10:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaushik N, Agnihotri A. Evaluation of improved method for determination of rapeseed-mustard FAMEs by GC. Chromatographia. 1997;44:97–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02466522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatterjee D, Bhattacharjee P. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of eugenol from clove buds. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2013;6:2587–2599. doi: 10.1007/s11947-012-0979-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng DY, Robinson DB. A new two-constant equation of state. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1976;15:59–64. doi: 10.1021/i360057a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valenzuela L, Valle JM. Fuente JDL. Modelling of carotenoids solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide using quantitative structure-property relationships. pp 1–8. In: III Iberoamerican Conference on Supercritical Fluids, Cartagena de Indias Colombia (2013).

- 23.Nejad SJ, Abolghasemi H, Moosavian MA, Maragheh MG. Prediction of solute solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide: A novel semi-empirical model. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2010;88:893–898. doi: 10.1016/j.cherd.2009.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ismadji S, Bhatia SK. Solubility of selected esters in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2003;27:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0896-8446(02)00190-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catchpole OJ, von Kamp JC. Phase equilibrium for the extraction of squalene from shark liver oil using supercritical carbon dioxide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997;36:3762–3768. doi: 10.1021/ie970224z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westerman D, Santos RCD, Bosley JA, Rogers JS, Al-Duri B. Extraction of amaranth seed oil by supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2006;37:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2005.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pal S, Bhattacharjee P. Nutraceutical food products using lutein-rich supercritical carbon dioxide extract of marigold flowers: product characterization and storage studies. Nutrafoods. 2017;16:19–29. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma Q, Xu X, Gao Y, Wang Q, Zhao J. Optimisation of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of lutein esters from marigold (Tagetes erect L.) with soybean oil as a co-solvent. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2008;43:1763–1769. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2007.01694.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montgomery DC. Response surface methods and other approaches to process optimization, design and analysis of experiments. New York, USA: John Wiley and Sons; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ge Y, Ni Y, Yan H, Chen Y, Cai T. Optimization of the supercritical fluid extraction of natural vitamin E from wheat germ using response surface methodology. J. Food Sci. 2002;67:239–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2002.tb11391.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prieto MSG, Castillo MLR, Flores G, María GS, Blanch GP. Application of Chrastil’s model to the extraction in SC-CO2 of β-carotene and lutein in Mentha spicata L. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2007;43:32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2007.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosh PK, Bhattacharjee P. Mathematical modeling of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of methyl eugenol from tuberose flowers. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2016;33:1681–1691. doi: 10.1007/s11814-015-0247-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simopoulos AP, Cleland LG. Omega–6/omega–3 essential fatty acid ratio: The scientific evidence in World review of nutrition and dietetics, ISSN 0084-2230, 92 (2003).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.