Abstract

Persistent spin texture (PST) is the property of some materials to maintain a uniform spin configuration in the momentum space. This property has been predicted to support an extraordinarily long spin lifetime of carriers promising for spintronics applications. Here, we predict that there exists a class of noncentrosymmetric bulk materials, where the PST is enforced by the nonsymmorphic space group symmetry of the crystal. Around certain high symmetry points in the Brillouin zone, the sublattice degrees of freedom impose a constraint on the effective spin–orbit field, which orientation remains independent of the momentum and thus maintains the PST. We illustrate this behavior using density-functional theory calculations for a handful of promising candidates accessible experimentally. Among them is the ferroelectric oxide BiInO3—a wide band gap semiconductor which sustains a PST around the conduction band minimum. Our results broaden the range of materials that can be employed in spintronics.

Persistent spin texture (PST) can generate fascinating physics that is promising for spintronics applications but requires non-trivial sample design. Here the authors alternatively propose that a class of materials has intrinsic PST enforced by the nonsymmorphic space group symmetry of the crystal.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in materials and structures, where quantum effects are responsible for novel physical properties, revealing the important roles of symmetry, topology, and dimensionality1. Among such quantum materials are graphene, topological insulators, Weyl semimetals, and superconductors. In many cases, the quantum materials derive their properties from the interplay between the electron, spin, lattice, and orbital degrees of freedom, resulting in complex physical phenomena and emergent functionalities2. These new functionalities are interesting due to their potential for a continuously evolving field of spintronics3.

Regarding the new phenomena, often a special role is played by the spin–orbit coupling (SOC), which on its own has inspired a vast number of predictions, discoveries, and novel concepts4. In a system, lacking an inversion center, the SOC results in an effective momentum-dependent magnetic field acting on spin σ. This field Ω(k) is odd in the electron’s wave vector (k), as was first demonstrated by Dresselhaus5 and Rashba6, so that the effective SOC Hamiltonian can be written as

| 1 |

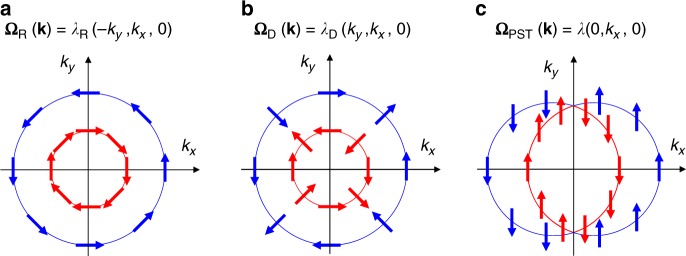

preserving the time-reversal symmetry. The specific form of Ω(k) depends on the space symmetry of the system. For example, in case of the C2v point group, the Dresselhaus and Rashba SOC fields can be written as and , respectively. Such SOC leads to a chiral spin texture of the electronic bands in the momentum space, as shown in Fig. 1a, b. The chiral spin textures driven by the SOC can be exploited to create nonequilibrium spin polarization7, produce the spin Hall effect8, and design a spin field-effect transistor (FET)9. Recently, these and other related phenomena have received significant attention and led to the emergence of a new field of research—spin-orbitronics4.

Fig. 1.

Spin texture. a–c Spin structure resulting from spin-orbit coupling in a system lacking an inversion center: Rashba (a), Dresselhaus (b), and persistent spin texture (c) configurations. Blue and red arrows indicate spin orientation for the two electronic subbands resulting from SOC. Expressions for the respective SOC fields are shown. Note that is represented in the coordinate system with the x- and y-axes being perpendicular to the mirror planes of an orthorhombic system (Mx and My in Fig. 2a)

Although large SOC is beneficial for realizing these phenomena, it plays a detrimental role for the spin life time. In a diffusive transport regime, impurities and defects scatter electrons, changing their momentum and randomizing the spin, due to the momentum-dependent spin–orbit field . This process is known as the Dyakonov-Perel spin relaxation10, reduces the spin life time and, thus limits the performance of potential spintronic devices, e.g., the spin FET. A possible way to circumvent this effect is to engineer a structure, where the spin–orbit field orientation is momentum-independent11. This can be achieved, in particular, if the magnitudes of and are equal, i.e., , resulting in a unidirectional spin–orbit field, or , and thus a momentum-independent spin configuration, known as the persistent spin texture (PST) (Fig. 1c)12.

Under these conditions, electron motion is accompanied by spin precession around the unidirectional spin–orbit field, resulting in a spatially periodic mode known as a persistent spin helix (PSH)13. The PSH state arises due to the SU(2) spin rotation symmetry, which is robust against spin-independent disorder and renders an ultimately infinite spin lifetime14. The PSH has been experimentally demonstrated in the two-dimensional electron gas semiconductor quantum-well structures, such as GaAs/AlGaAs15,16 and InGaAs/InAlAs17,18, where the required condition of equal Rashba () and Dresselhaus () parameters was realized through tuning the quantum-well width, doping level, and applied external electric field.

Despite these advances, a number of difficulties impede the practical application and further experimental studies of these semiconductor heterostructures. Satisfying the stringent condition of equal and parameters is technically nontrivial because it requires a precise control of the quantum-well width and the doping level. Furthermore, due to the small values of these parameters (a few meV Å), efficient spin manipulation by an applied electric field is questionable. Recently, based on first-principles calculations a PST was predicted for a wurtzite ZnO surface19 and a tensile-strained LaAlO3/SrTiO3 (001) interface20. However, for the latter, too large tensile strain (>5%) is required to achieve the desired property, whereas for the former, the SOC energy splitting is too small (~1 meV). It would be desirable to find bulk materials where the PST is a robust intrinsic bulk property. Recently, SnTe (001) thin films have been proposed to realize a PSH21.

Here, we propose a conceptually different approach to achieve the PST. We demonstrate that there exist a class of noncentrosymmetric bulk materials where the PST is enforced by nonsymmorphic space group symmetry of the crystal, i.e., the space group combining point-group symmetry operations with nonprimitive translations22. Around certain high symmetry points in the Brillouin zone, the sublattice degrees of freedom impose a constraint on the effective spin–orbit field, which orientation remains independent of the momentum and thus maintains PST. The symmetry-enforced PST survives over the large part of the Brillouin zone including band edges, as we demonstrate using density-functional theory (DFT) calculations for BiInO3 and other materials with appropriate crystal group symmetry.

Results

Symmetry analysis

We consider orthorhombic nonsymmorphic crystals with broken space inversion symmetry (space groups listed in Table 1)22. Figure 2a shows an orthorhombic crystal lattice, which contains the following symmetry operations: (1) the identity operation E; (2) glide reflection , which consists of mirror reflection about the x = 0 plane followed by the translation:

| 2 |

Table 1.

Classification of orthorhombic space groups with no inversion symmetry according to translation vectors characterized by indices (μ2v1). Nonzero spin components in high symmetry points and band degeneracy along high symmetry lines are shown

| (μ2 ν1) | X | Y | Band degeneracy | Space group no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | X–S | 28, 29, 31, 40, 46 | ||

| – | Y–S | 30, 39 | ||

| X–S and Y–S | 32, 33, 34, 41, 45 |

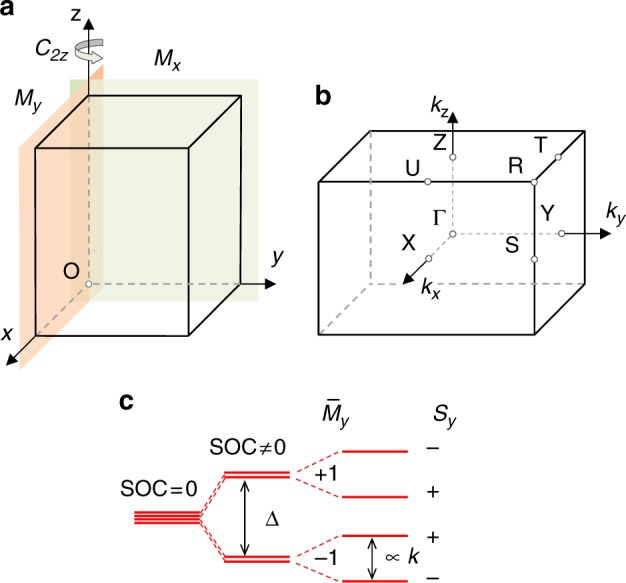

Fig. 2.

Crystal lattice and energy band splitting. a Orthorhombic crystal lattice with symmetry operations indicated. denotes a twofold rotation operator, and and represent two mirror reflection operators. b The first Brillouin zone with the high symmetry k points indicated: Γ (0, 0, 0), X (π, 0, 0), S (π, π, 0), Y (0, π, 0), Z (0, 0, π), U (π, 0, π), R (π, π, π), and T (0, π, π), the k point coordinates are given in units of the reciprocal lattice constants. c Schematic splitting of the energy levels around the X point. SOC splits the state into two doublets with eigenvalues of , which are further split into singlets with sign-reversed expectation values of . The energy level order labeled by and is material dependent

(3) glide reflection , which consists of mirror reflection about the y = 0 plane followed by the translation:

| 3 |

(4) two fold screw rotation , which consists of twofold rotation around the z-axis followed by the translation:

| 4 |

Here and below, the translation and reciprocal vectors are given in units of lattice constants and (i = 1, 2, 3). The glide (screw) symmetry is reduced to mirror (rotation) symmetry if . In addition, we assume that the system exhibits time-reversal symmetry T.

Now, we demonstrate the formation of the PST around the X point in the Brillouin zone of the crystal (Fig. 2b). First, we consider the X–S high symmetry line . Along this line, the little group of wave vector k includes the symmetry operators and , as follows from being invariant under the transformations determined by these symmetry operators. Since for a spin-half system, we find . Therefore, for the space groups with , along the X–S line, so that all bands are double degenerate. The doublet states form a Kramers pair.

At the X point, commutes with the Hamiltonian of the crystal, i.e., , and the doublet can be labeled using the eigenvalues of . Since at this point, we have and . Thus, by symmetry, there are two conjugated doublets at the X point, or , which are distinguished by the eigenvalues. Within each of the two doublets, matrix elements of the spin operators and are equal to zero. This is due to the fact that in the spin space anticommutes with and , i.e., , which results in , and hence . The similar analysis leads to and . The same conclusion holds for the other doublet .

We see, therefore, that any state, which represents a linear combination of the states comprising either doublet, i.e., (where and are some coefficients), has zero expectation values of and zero spin components . The only nonzero component of the spin is, therefore, . Thus, as long as the two doublets are not mixed, the spin orientation is forced to be along the y-direction.

This explains the PST around the X point. At the X point the SOC splits the fourfold degenerate state into two doublets with splitting Δ and eigenvalues of , as shown in Fig. 2c. When moving away from this point the perturbation breaks the X point symmetry and further splits the doublets, each into two singlets (unless going along the X–S symmetry line). These states preserve the unidirectional spin texture along the y-direction unless the perturbation is so strong that it mixes the doublets. However, due to the perturbation being linear with respect to k (measured from the X point), there is always a range of k vectors, where it is small compared to the splitting between the doublets. In practice, this range of k values may be substantial and can span a large portion of the Brillouin zone including the band edges responsible to transport and optical properties in semiconductor materials.

A similar analysis applies to the Y point, where (Fig. 2b). The bands are double degenerate along the high symmetry Y–S line, where , provided that . The wave functions at the Y point are the eigenstates of the spin component . A portion of the Brillouin zone around the Y point maintains the PST with the spin pointing along the x-direction. In Table 1 we classify space groups of the orthorhombic crystal system according to the value and show those spin components which remain nonzero around the respective high-symmetry points.

DFT analysis of bulk BiInO3

In the following, we reinforce our symmetry-based conclusions by performing DFT calculations for a number of bulk compounds, which belong to selected space groups listed in Table 1. Details of the DFT calculations are described in Section Methods. First, we focus on perovskite BiInO3 (space group No. 33), which has been synthesized experimentally and is stable at ambient conditions23. The BiInO3 crystal structure (Fig. 3) belongs to the Pna21 orthorhombic phase (space group No. 33). The symmetry operations of this group involve the glide reflection (2) with , the glide reflection (3) with and the twofold screw rotation (4) with . The BiInO3 crystal structure is derived from the centrosymmetric GdFeO3-type perovskite structure (Pnma group) through polar displacements, which break space inversion symmetry. As seen from Fig. 3a, each bismuth or indium atom in the BiInO3 structure is surrounded by a distorted oxygen octahedron typical for the GdFeO3-type perovskite structure. In addition, there are polar displacements seen, e.g., in Fig. 3b from displacement of Bi3+ ions (~0.25 Å) from their symmetric positions with respect to the mirror Pnma plane (dotted line in Fig. 3b). The polar displacements yield a finite polarization pointing in the [001] direction. There are two topologically equivalent variants of the space group Pna21 with opposite polarization (pointing in the or directions) indicative to the ferroelectric nature of BiInO3. The calculated polarization is about 33.6 μC/cm2.

Fig. 3.

Crystal structure of bulk BiInO3. a 3D view of the unit cell structure. b, c View of the crystal structure in the (100) plane (b) and the (001) plane (c). The twofold screw rotation axis () and the glide reflection planes ( and ) are indicated by the dashed lines. The dotted line indicates a Pnma symmetry mirror plane

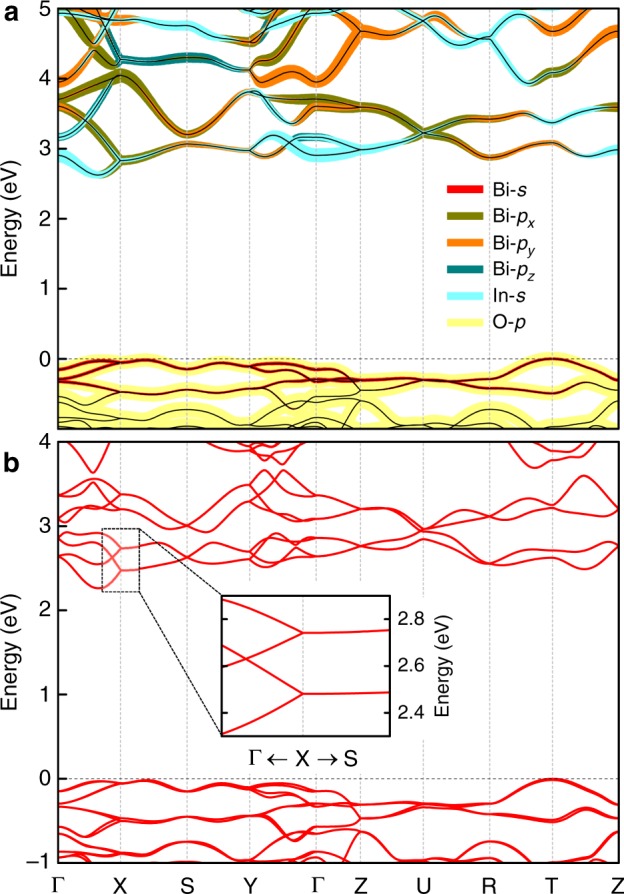

Figure 4a shows the calculated band structure of BiInO3 without SOC along high-symmetry lines in the Brillouin zone (shown in Fig. 2b). We find that the conduction bands are mostly composed of the hybridized Bi-6p and In-5s orbitals, whereas the valence bands are dominated by the O-2p orbitals with a small admixture of the Bi-6s states. It is seen from Fig. 4a that BiInO3 is an indirect band-gap semiconductor with the valence band maximum located at the T point and the conduction band minimum (CBM) located along the Γ–X symmetry line. The calculated band gap is about 2.6 eV.

Fig. 4.

Band structure of bulk BiInO3. a, b Band structure along the high symmetry lines in the Brillouin zone without SOC (a) and with SOC (b). Orbital-contributions in panel a are shown by color lines with thickness proportional to the orbital weight. Inset in panel b shows the band structure zoomed in around the X point

Including SOC (Fig. 4b) reduces the band gap to about 2.3 eV and strongly affects the electronic structure of conduction bands of BiInO3. Comparing the band structures calculated with SOC (Fig. 4b) and without SOC (Fig. 4a), a sizable band spin splitting produced by the SOC is seen at some high symmetry k points and along certain k paths. At the X point, which is located in the proximity of the CBM, the two lower energy states are doublets resulting from the SOC splitting. The splitting is large, i.e., Δ ≈ 0.26 eV. As expected, the bands along the X–S line are double degenerate protected by the symmetry. When moving from the X to Γ point the doublets are split into singlets with a nearly linear dispersion (see inset of Fig. 4b).

Lifting the degeneracy along the Γ–X line, where , can be understood from the little group of wave vector k, which has symmetry generators and . Along this line and thus the Bloch states and are not degenerate. In addition, each state can be labeled using the eigenvalues of . Since , we obtain . Therefore, there are four nondegenerate Bloch states, and , evolving from the X point when moving along the X–Γ line (inset of Fig. 4b). Interestingly, crossing the and bands is enforced and protected by symmetry, resulting in a hourglass-shaped band dispersion24,25 (see Supplementary Note 1).

The SOC splitting at the Y point is smaller Δ ≈ 0.09 eV. The bands along the Y–S line are double degenerate protected by the symmetry, but split when moving from the Y to Γ point. This behavior can be understood using the considerations similar to those we used to explain band degeneracies and splittings around the X point.

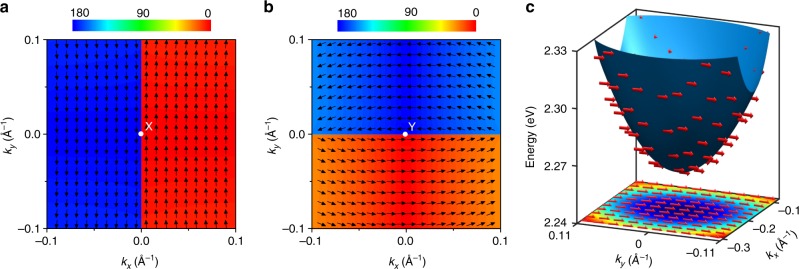

Next, we explore the spin texture around the X and Y points. According to Table 1, the space group No. 33 for BiInO3 supports the PST with the uniform spin orientation along the y (x) axis around the X (Y) point. This is exactly what we find from our DFT results. Figure 5a shows the calculated spin texture around the X point for the conduction band, which has the lowest energy. We see a unidirectional spin configuration for positive and negative values of kx (referred to the origin being at the X point), which is consistent with the effective SOC field and the PST in Fig. 1. As expected, the spin orientation changes abruptly at kx = 0, where the sy component of the spin is reversed. We note that there is another band (with the opposite eigenvalue if moving along the X–Γ line), which has higher energy (except the X–S line where it has the same energy) for which the spin has opposite orientation.

Fig. 5.

Spin texture of BiInO3. a, b Spin configurations around the high-symmetry k points: X point a and Y point b. The spin textures are plotted in the kz = 0 plane for the lowest energy conduction bands. The wave vector k is referenced to the X point (a) and Y point (b), where it is assumed to be zero. The color map reflects the polar angle (in degrees) with respect to the y-axis (a) and x-axis (b). c 3D diagram and 2D projection of band structure and spin texture around the CBM. The arrows indicate the spin direction. The color map shows the energy profile. The wave vector is referenced to the X point where is it assumed to be zero

It is remarkable that the PST covers a substantial part of the Brillouin zone. The range of kx and ky values in Fig. 5a spans 0.2 Å−1 around the X point. For comparison, the x component of the reciprocal wave vector is π/a = 0.528 Å−1 (distance from the to X to Γ point). In fact, the nearly uniform spin structure persists even at larger distances and covers the CBM, which is located at about 0.19 Å−1 from the X point along the X–Γ line. Figure 5c shows the band dispersion and the spin structure around the CBM. It is evident that the spin maintains nearly unidirectional texture along the y-direction, which is reminiscent to that at the X point. Our calculations predict that in the range of kx and ky values spanning 0.2 Å−1 around the CBM (as in Fig. 5c), the largest deviation of the spin orientation from the y-axis is only 9.6°. This is due the CBM-forming band being well separated from the other two bands derived from the higher energy doublet (inset of Fig. 4b), so that the mixing between the doublets is minor. We note that the PST around the CBM is fully reversed when the wave vector k is changed to –k, due to time reversal symmetry.

The spin structure around the Y point (Fig. 5b) shows the similar trend, now with the spin being textured along the x-direction. The effective SOC field in this case leads to reversal of the sx component when crossing the ky = 0 line. There is a visible deviation from the unidirectional spin orientation when moving far away from the Y point. This stems from the reduced SOC splitting at the Y point (Δ ≈ 0.09 eV) as compared to that the X point (Δ ≈ 0.26 eV).

A model. The spin textures around the high symmetry points can be further understood in terms of an effective Hamiltonian, which we deduce from symmetry considerations. Here, we focus on the X point. In order to describe the four dispersing bands around the X point, additional sublattice degrees of freedom need to be included in the consideration. These are conventionally described by a set of Pauli matrices (j = x, y, z) operating in the sublattice space. The Hamiltonian around the X point is constructed by taking into account all symmetry operations at the X point, at which the symmetry generators are and , and the time-reversal symmetry, which operator is , where K is complex conjugation. We find that and can be represented as and (see Supplementary Note 2). Collecting all the terms up to linear order in k, which are invariant under these symmetry transformations, we obtain the Hamiltonian:

| 5 |

Here, for simplicity we limit our consideration by the plane; δ, α, β, γm (m = 1–4) are independent parameters, and are the 2 × 2 identity matrices, and direct products (i, j = 0, x, y, z) are implicitly assumed.

When k = 0 (i.e., at the X point), the term in the Hamiltonian splits the state into two doublets distinguished by the eigenvalues of and separated by . When k is not too large, the other terms in the Eq. (5) can be treated as perturbation. In the first order, the perturbation does not mix the doublets and the effective Hamiltonian within each of the doublets (labeled by indices ) can be written as

| 6 |

where (see Supplementary Note 2). The corresponding eigenvalues are

| 7 |

i.e., each doublet is split into two singlet states exhibiting linear dispersion away from the X point. This is consistent with our DFT results (inset in Fig. 4b). Fitting the DFT energy bands yields the following parameters: eV, eV Å, eV Å. Other parameters in the Hamiltonian of Eq. (5), can be found from the expectation values of the y-component of the spin, and , for the doublet (+) and doublet (–), respectively. Using the DFT results for , we obtain eV Å, eV Å, eV Å, and eV Å.

The effective Hamiltonian of Eq. (6) imposes the effective SOC field pointing along the y-direction, i.e., , where , which produces the PST (Fig. 1c). Importantly, this form of the PST Hamiltonian appears as the result of the crystal symmetry rather than matching the Rashba and Dresselhaus constants. For the lowest energy band, and the spin is parallel (antiparallel) to the y-direction for positive (negative) kx. This is in agreement with the spin structure in Fig. 5a obtained from our DFT calculations.

Including first-order perturbation corrections to the wave function mixes states between the doublets, resulting in nonvanishing components of sx and sz and thus deviation from the PST. Our detailed analysis (see Supplementary Note 3) shows that within this approximation the component of the spin remains constant (Supplementary Eq. 21), whereas the component varies as (for the lowest conduction band), where q is a SOC constant (Supplementary Eq. 22). It is evident from this result that, first, at , and hence the spin orientation remains collinear to the y-axis at the CBM ( Å−1, ) as at the X point, and, second, when going away from the CBM along the value changes linear with . Nonzero produces deviation from PST, but this deviation remains small over a broad area around the CBM due to the large splitting Δ. This is evident from Supplementary Fig. 3, which also reveals excellent agreement between the perturbation theory and explicit DFT calculation. This approach also allows us to obtain the remaining SOC constants in Hamiltonian of Eq. (5), eV Å and eV Å, as detailed in Supplementary Note 3.

We would like to note that for the compounds considered in our work, any order terms in k in the Hamiltonian preserve PST in zero-order perturbation theory. Only in the first order of perturbation theory for the wave function a deviation from PST occurs with the dominant contribution resulting from linear in k terms. However, due to this contribution occurring as a perturbation, deviation from the PST remains small over a large area of the Brillouin zone.

Discussion

The obtained value of the SOC parameter λ = 1.91 eV Å is three orders of magnitude larger than the values known for the semiconductor quantum-well structures (1–5 meV Å)15–18. It is also larger than the values predicted for other ferroelectric oxides, e.g., 0.74 eV Å for BiAlO3 (P4mm space group)26 and 0.58 eV Å for HfO2 (Pca21 space group)27, and comparable to the value of 3.85 eV Å observed in BiTeI28. The associated band splittings are sufficient to support room temperature functionalities. For example, the lowest excited state at corresponding to the CBM lies about 0.29 eV above the CBM.

Electron motion in the PST state forms persistent spin helix (PSH)—the spatially periodic mode of spin polarization with the wave length of 13. We estimate the effective mass m in BiInO3 by fitting the band dispersion around the CBM, which leads to m = 0.61m0, where m0 is the free electron mass. The resulting wave length is about 2 nm. This value is three orders of magnitude smaller than observed in semiconductor heterostructures16.

It is conceivable (though challenging) to form and map a PSH state in BiInO3 in spirit of experiments by Walser et al.16. BiInO3 is a wide band gap semiconductor, and in order to observe this property an electron doping is required. Since Bi is isovalent to In, In2O3 may be considered as a comparative compound. It is known that oxygen vacancies naturally form in In2O3 producing n-type conductivity which can be varied over a broad range of magnitudes by changing growth conditions (mainly oxygen pressure)29. We expect, therefore, that a similar approach could be employed to produce electron doping in BiInO3. Due to CBM in BiInO3 maintaining PST, a PSH state will be formed if electrons are optically injected into the conduction band of BiInO3. Mapping the formation and evolution of PSH in BiInO3 could possibly be performed using near-field scanning Kerr microscopy, which showed a possibility to resolve features down to tens-nm scale with sub-ns time resolution30. In addition, the electron-doped BiInO3 can be used to explore the current induced spin polarization (known as the Edelstein effect7) and associated spin-orbit torques31, which are expected to be large due to the large SOC.

We also envision a possibility to observe a Hall effect qualitatively similar to the valley Hall effect recently discovered in transition metal dichalcogenides (TMD)32. In BiInO3 the two states with k and -k at the CBM with opposite spin orientation are related by time reversal symmetry transformation and thus have opposite sign of the Berry curvature. If an imbalance in electron population between these two states is created by polarized optical excitation (similar to that done in TMDs), a charge Hall current can be measured that reverses sign with polarization of the exciting light.

Another implication is a possibility to use a PST material as a barrier in tunnel junctions. It has been predicted that the Rashba and Dresselhaus SOC in a tunnel barrier can produce tunneling anomalous and spin Hall effects33,34. Using a PST material as a tunnel barrier allows producing a perfect anisotropy in the Hall response. For example, if the current flows in the z-direction across a PST barrier with the SOC given by Eq. (6), the tunneling Hall response will be zero in the y-direction and nonzero in the x-direction. Moreover, the anomalous Hall conductivity is expected to strongly depend on the magnetization orientation in the x–y plane and vanish for magnetization pointing along the x-direction. The large value of λ = 1.91 eV Å is expected to produce sizable effects, which can be detected experimentally. In addition, the reversible spin texture of ferroelectric SOC oxide materials35,36 will support the tunneling Hall effects to be reversible by an applied electric field through switching of ferroelectric polarization27.

Apart from BiInO3, there are a number of other potential candidates which are expected to maintain a PST. Among them are BiInS3 (Pna21 structure, space group No. 33) and LiTeO3 (Pnn2 structure, space group No. 34). Both have a PST around the high symmetry X and Y points (see Supplementary Note 4). BiInS3 has a lower calculated band gap (about 1.13 eV), but a CBM is located at the Γ point, which does not support the PST. On the other hand, LiTeO3 (calculated band gap is about 2 eV) has a CBM close to the X point similar to BiInO3.

Overall, we have demonstrated that the PST is imposed by symmetry in a class of orthorhombic nonsymmorphic bulk materials, such as BiInO3. The PST is a robust intrinsic property of these materials, which eliminates the stringent condition of equal Rashba and Dresselhaus SOC for realizing the persistent spin helix. The electronic and spin properties of the PST materials are derived from the nontrivial interplay between spin–orbit coupling and glide reflection symmetries, and in this regard place them among interesting quantum materials which have recently received a lot of attention. We hope, therefore, that our theoretical predictions will stimulate experimental efforts in the exploration of these materials, which functional properties may be useful for device applications.

Methods

DFT calculations

DFT calculations are performed using a plane-wave pseudopotential method implemented in Quantum-ESPRESSO37. In the calculations, we use the lattice constants and atomic positions of bulk materials, which are given in Supplementary Note 4. The exchange-correlation functional is treated within the generalized gradient approximation38. We use energy cutoff of 544 eV for the plane wave expansion and 10 × 10 × 8 k-point grid for Brillouin zone integrations. The electric polarization is computed using the Berry phase method39. SOC is included in the calculations using the fully relativistic ultrasoft pseudopotentials40. The expectation values of the spin operators (i = x, y, z) are obtained directly from the noncollinear spin DFT calculations. The atomic structures are produced using VESTA software41.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Nebraska Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC) (Grant No. DMR-1420645). Computations were performed at the University of Nebraska Holland Computing Center. The authors thank Jaroslav Fabian, Jairo Sinova, Silvia Picozzi, and Alexei Kovalev for helpful discussions.

Author contributions

L.L.T. and E.Y.T conceived the project. L.L.T. carried out DFT calculations. L.L.T. and E.Y.T. performed the symmetry analysis and theoretical modeling. Both authors discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-05137-0.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Keimer B, Moore JE. The physics of quantum materials. Nat. Phys. 2017;13:1045–1055. doi: 10.1038/nphys4302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tokura Y, Kawasaki M, Nagaosa N. Emergent functions of quantum materials. Nat. Phys. 2017;13:1056–1068. doi: 10.1038/nphys4274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsymbal, E. Y. & Žutić, I., Eds., Handbook of spin transport and magnetism (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 2012), 808 pp.

- 4.Manchon A, Koo HC, Nitta J, Frolov SM, Duine RA. New perspectives for Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Nat. Mater. 2015;14:871. doi: 10.1038/nmat4360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dresselhaus G. Spin–orbit coupling effects in zinc blende structures. Phys. Rev. 1955;100:580–586. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.100.580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rashba E. Properties of semiconductors with an extremum loop. 1. Cyclotron and combinational resonance in a magnetic field perpendicular to the plane of the loop. Sov. Phys. Solid State. 1960;2:1109–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edelstein VM. Spin polarization of conduction electrons induced by electric current in two-dimensional asymmetric electron systems. Sol. State Commun. 1990;73:233–235. doi: 10.1016/0038-1098(90)90963-C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyakonov MI, Perel VI. Possibility of orienting electron spins with current. Sov. Phys. JETP Lett. 1971;13:467–469. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datta S, Das B. Electronic analog of the electro-optic modulator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1990;56:665–667. doi: 10.1063/1.102730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyakonov M, Perel V. Spin relaxation of conduction electrons in noncentrosymmetric semiconductors. Sov. Phys. Solid State. 1972;13:3023–3026. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schliemann J, Egues JC, Loss D. Nonballistic spin-field-effect transistor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;90:146801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.146801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schliemann J. Colloquium: persistent spin textures in semiconductor nanostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2017;89:011001. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.89.011001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernevig BA, Orenstein J, Zhang SC. Exact SU(2) symmetry and persistent spin helix in a spin–orbit coupled system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:236601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.236601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kammermeier M, Wenk P, Schliemann J. Control of spin helix symmetry in semiconductor quantum wells by crystal orientation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016;117:236801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.236801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koralek JD, et al. Emergence of the persistent spin helix in semiconductor quantum wells. Nature. 2009;458:610–613. doi: 10.1038/nature07871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walser MP, Reichl C, Wegscheider W, Salis G. Direct mapping of the formation of a persistent spin helix. Nat. Phys. 2012;8:757–762. doi: 10.1038/nphys2383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohda M, et al. Gate-controlled persistent spin helix state in (In,Ga)As quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;86:081306. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.86.081306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasaki A, et al. Direct determination of spin–orbit interaction coefficients and realization of the persistent spin helix symmetry. Nat. Nanotech. 2014;9:703. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Absor MAU, Ishii F, Kotaka H, Saito M. Persistent spinhelix on a wurtzite ZnO (10 10)surface: first-principles density-functional study. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2015;8:073006. doi: 10.7567/APEX.8.073006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaguchi N, Ishii F. Strain-induced large spin splitting and persistent spin helix at LaAlO3/SrTiO3interface. Appl. Phys. Exp. 2017;10:123003. doi: 10.7567/APEX.10.123003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, H., Im, J. & Jin, H. Harnessing the giant out-of-plane Rashba effect and the nanoscale persistent spin helix via ferroelectricity in SnTe thin films. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1712.06112 (2018).

- 22.Bradley C. J. & Cracknell, A. P. The mathematical theory of symmetry in solids: representation theory for point groups and space groups (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972).

- 23.Belik AA, Stefanovich SY, Lazoryak BI, Takayama-Muromachi E. BiInO3: a polar oxide with GdFeO3-type perovskite structure. Chem. Mater. 2006;18:1964–1968. doi: 10.1021/cm052627s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z, Alexandradinata A, Cava RJ, Bernevig BA. Hourglass fermions. Nature. 2016;532:189–194. doi: 10.1038/nature17410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bzdušek T, Wu QS, Rüegg A, Sigrist M, Soluyanov AA. Nodal-chain metals. Nature. 2016;538:75–78. doi: 10.1038/nature19099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.da Silveira LGD, Barone P, Picozzi S. Rashba-Dresselhaus spin-splitting in the bulk ferroelectric oxide BiAlO3. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;93:245159. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.245159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao LL, Paudel TR, Kovalev AA, Tsymbal EY. Reversible spin texture in ferroelectric HfO2. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;95:245141. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.245141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishizaka K, et al. Giant Rashba-type spin splitting in bulk BiTeI. Nat. Mater. 2011;10:521–526. doi: 10.1038/nmat3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bierwagen O. Indium oxide—a transparent, wide-band gap semiconductor for (opto)electronic applications. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2015;30:024001. doi: 10.1088/0268-1242/30/2/024001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudge J, Xu H, Kolthammer J, Hong YK, Choi BC. Sub-nanosecond time-resolved near-field scanning magneto-optical microscope. Rev. Sci. Instr. 2015;86:023703. doi: 10.1063/1.4907712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gambardella P, Miron IM. Current-induced spin–orbit torques. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2011;369:3175–3197. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2010.0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mak KF, McGill KL, Park J, McEuen PL. The valley Hall effect in MoS2 transistors. Science. 2014;344:1489–1492. doi: 10.1126/science.1250140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vedyayev AV, Titova MS, Ryzhanova NV, Zhuravlev MY, Tsymbal EY. Anomalous and spin Hall effects in a magnetic tunnel junction with Rashba spin–orbit coupling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013;103:032406. doi: 10.1063/1.4815866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matos-Abiague A, Fabian J. Tunneling anomalous and spin Hall effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015;115:056602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.056602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Sante D, Barone P, Bertacco R, Picozzi S. Electric control of the giant Rashba effect in bulk GeTe. Adv. Mater. 2013;25:509–513. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tao LL, Wang J. Strain-tunable ferroelectricity and its control of Rashba effect in KTaO3. J. Appl. Phys. 2016;120:234101. doi: 10.1063/1.4972198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giannozzi P, et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2009;21:395502. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/39/395502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.King-Smith RD, Vanderbilt D. Theory of polarization of crystalline solids. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;47:1651. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vanderbilt D. Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys. Rev. B. 1990;41:7892. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.41.7892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Momma K, Izumi F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011;44:1272–1276. doi: 10.1107/S0021889811038970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon request.