Abstract

Previous research on attributions in schizophrenia has focused on whether individuals make hostile, intentional attributions for ambiguous negative events. It is unclear, however, whether individuals with schizophrenia differ from controls in their general judgments of intentionality judgments in non-conflict and emotionally neutral situations. Research in social psychology suggests that non-clinical individuals present with an automatic bias to see intentionality, and that this bias is regulated by the operation of controlled processes. The present study examined whether this general intentionality bias distinguishes individuals with schizophrenia (n = 213) from non-patient controls (n = 151). Indeed, individuals with schizophrenia were more likely to attribute intentional motives to others’ actions relative to controls. This intentionality bias was related to hostility, role functioning, and independent living skills. These findings may provide one domain to examine in future approaches to social cognition in schizophrenia.

Keywords: schizophrenia, social cognition, functioning, psychometrics

Introduction

Individuals with schizophrenia are consistently impaired in social cognition (Savla et al., 2013), or “the mental operations that underlie social interactions, including perceiving, interpreting, and generating responses to the intentions, dispositions, and behaviors of others” (Green et al., 2008, p. 1211). Social cognition is separable theoretically and statistically from neurocognition (Allen et al., 2007; van Hooren et al., 2008), is itself a robust predictor of concurrent (Couture, Penn & Roberts, 2006; Fett et al., 2011) and prospective (Horan et al., 2012) functioning, and is responsive to psychosocial interventions (Kurtz & Richardson, 2011). Social cognition comprises two categories: (1) abilities to correctly interpret social information, or social cognitive skills and (2) specific patterns in open-ended interpretations of social situations, or social cognitive biases (Mancuso et al., 2011; Roberts & Pinkham, 2013).

Unlike social cognitive skills, that assess one’s ability to correctly respond in a right-or wrong manner, social cognitive biases examine patterns of responses in certain social circumstances. For example, individuals with schizophrenia tend to regard others’ intentions as hostile and intentional in ambiguous negative situations (hostile attribution bias; Chang et al., 2009; Combs et al., 2009; Buck et al., 2017; Lahera et al., 2015; Kanie et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2014), and those experiencing persecutory delusions also show greater likelihood of blaming others for negative events (externalizing bias; Bentall & Kaney, 2005; Combs et al., 2009; Craig et al., 2004; Jolley et al., 2006; Mehl et al., 2010; Randall et al., 2003) and attribute the cause of fewer events—regardless of valence—to themselves (self-causation bias; Aakre et al., 2009; Diez-Alegria et al., 2006; Lincoln et al., 2010; Moritz et al., 2010; Randall et al, 2003; Randjbar et al., 2011). These biases provide information about the severity of persecutory delusions or paranoia (Combs et al., 2007b, 2009; Craig et al., 2004; Mehl et al., 2010, 2014; Kinderman & Bentall, 1997b; Langdon et al., 2006; Langdon, Ward & Coltheart, 2010; Lincoln et al., 2010), depressive symptoms (Candido & Romney, 1990; Fraguas et al., 2008; Krstev, Jackson & Maude, 1999; Mancuso et al., 2011; Martin & Penn, 2002; Sanjuan et al., 2009), attachment style (Donohoe et al., 2008), anxiety (le Gall et al., 2013), and clinical insight (Langdon et al., 2006).

However, recent studies have identified significant measurement challenges in this area. The Social Cognition Psychometric Evaluation study (SCOPE; Pinkham et al., 2014, 2016) identified attributional style as a critical domain of social cognition in the researcher survey and RAND panel phase, but found limitations with the one measure of this domain that was selected for psychometric evaluation, the Ambiguous Intentions Hostility Questionnaire (AIHQ; Combs et al., 2007). Because the AIHQ demonstrated no relationships to measures of outcome (i.e. social functioning, role functioning and functional capacity) and demonstrated weak test-retest reliability relative to other measures, it was not included in the final SCOPE battery (Pinkham et al., 2017). In place of the AIHQ, the latest phase of the SCOPE study (Pinkham et al., 2017) evaluated Rosset’s (2008) intentionality bias task (IBT). This task requires participants to quickly categorize ambiguous actions (e.g., “The girl popped the balloon”; “She sprayed him with water”) as occurring on purpose or by accident. By examining intentionality in neutrally-valenced situations, the IBT addresses one drawback of the AIHQ: the AIHQ confounds hostility and intentionality biases by exclusively measuring intentionality judgments in negatively-valenced situations. An overall increased tendency to see others’ actions as intentional could make social interactions confusing or threatening and thus contribute to social avoidance and dysfunction.

In SCOPE, psychometrics of the IBT were regarded as “acceptable with reservations” (Pinkham et al., 2017). An overall total score was used to index responses on the IBT, and this score differentiated clinical groups and was related to functional outcome. However, the IBT had suboptimal test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and was susceptible to practice effects. Given SCOPE’s focus on the psychometrics of the task as a whole, two important characteristics of the bias toward intentionality were not examined in these initial analyses. First, the bias toward intentionality is thought to comprise dual processes, or (1) immediate automatic judgments as well as (2) efforts of controlled cognitive processes to revise or override these initial quick judgments (Chaiken & Trope, 1999). The IBT includes both slow (5000 ms to respond) and fast (2400 ms to respond) conditions, and general population participants are significantly more likely in the fast condition to perceive prototypically accidental actions as intentional (Rosset, 2008). Based on these results, Rosset argues that people need to exert cognitive control to override an automatic tendency to perceive acts as intentional; in other words, people must effortfully “override and thus inhibit” the automatic tendency to view “everything anyone ever does as intentional” (p. 772; Rosset, 2008). When people are unmotivated or unable to exert cognitive control to produce a response (e.g., when they are under time pressure), then their response is guided by their automatic tendency.

Developments in methodology from social psychology allow researchers to separate the specific contributions of automatic and controlled processes to social judgments. Specifically, the process dissociation procedure (PDP; Jacoby, 1991) quantifies the extent to which individuals’ response patterns adhere to typical response patterns (gathered from untimed normative sample data). In this procedure, reliance on control is estimated as the participants’ ability to effortfully give “accurate” responses to vignettes. Reliance on automatic processes is estimated as the participants’ tendency to give a certain response when controlled processing fails. Further, a time pressure manipulation can examine how reliance on each of these processes changes when participants are less able to recruit effortful cognitive processes. When individuals with psychoses report biased social judgments, these reports may stem from especially biased automatic judgments or from difficulty controlling or correcting these initial biased judgments, which may be likely when considering associated cognitive impairments (Heinrichs & Zakzanis, 1998). Though overall scores are useful, estimates of automaticity and control may enhance our understanding of these biases in psychosis.

Finally, social cognitive biases, though often evaluated alongside social cognitive skills for their relationships to general functional outcomes (Mancuso et al., 2011; Pinkham et al., 2015), appear to provide information that is particularly useful in predicting domains related to interpersonal conflict (i.e., verbal and physical fights, paranoia, hostility; Buck et al., 2017) rather than composite scores of skills in living (i.e., work skill, independent living skills, social skills). An improved model of the relationship between social cognitive bias and outcomes is required before fully evaluating the effectiveness of assessment instruments of this domain. The intentionality bias task has not been evaluated in terms of its relationships to such criterion outcomes. Thus, the present study aims to expand on the initial psychometric evaluation of the intentionality bias provided in the SCOPE study by examining the automatic and controlled components that underlie an intentionality bias and testing a model of the domains (i.e. paranoia, hostility, interpersonal conflict) that intentionality bias are most likely to impact in psychosis. It is unclear at present whether the weak predictive ability of extant attribution measures stems from psychometric limitations of the measures or reflects a true lack of outcomes (counter to theoretical predictions; Buck et al., 2017). As the IBT is proposed to address several limitations of previous measures (i.e. the AIHQ; Combs et al., 2007), it is possible that this assessment will demonstrate relationships to both criterion outcomes and general functional outcomes. In this process, the present study gives a thorough introduction to the intentionality bias as a useful clinical metric.

Methods

Sample

Data collection was completed in the final phase of the SCOPE study (Pinkham et al., 2017), which recruited participants with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (n = 218) and healthy controls (n = 154) at three different research sites: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of Texas at Dallas, and University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. IRB approval was granted through all three institutions (UNC IRB #12-2548; UT Dallas IRB #14-52, University of Miami IRB HSRO #20110725) Of the entire sample, seven participants (n = 4 from the schizophrenia group; n = 3 from the clinical group) were removed for outlier scores on the IBT (full details in Pinkham et al., 2017). One participant in the schizophrenia group was also excluded for responding to zero items on the task, leaving a final sample of 213 participants with schizophrenia and 151 non-clinical controls. Trained research assistants confirmed participants’ diagnoses (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder) with a structured clinical interview. Participants with schizophrenia were included in the study if they were not hospitalized in the previous two months, were on a stable medication regimen for at least six weeks, and had no change in dose in two weeks. Participants in both groups were excluded if they met any of the following exclusion criteria: 1) current or past pervasive developmental disorder, 2) low IQ (< 70), 3) current or past medical or neurological conditions that may affect participation, 4) presence of sensory limitations that interfere with assessment, 5) presence of substance abuse in the past month, or 6) presence of substance dependence not in remission for at least 6 months.

Measures

Intentionality Bias Task (Rosset, 2008)

Participants completed a slightly modified version of Rosset’s (2008) intentionality bias procedure. This procedure presents participants with sentences varied according to their pre-rated intentionality (based on previously collected and untimed ratings), featuring half prototypically accidental (average of 25% of participants rating statement as intentional; e.g. “the girl popped the balloon”), and half prototypically intentional (average of 75% of participants rating statement as intentional; e.g. “he took an illegal left turn”) items. Participants determined whether these items describe actions that were done “on purpose” or “by accident” in blocks that varied whether participants had to respond either under high time pressure (2400 ms) or low time pressure (5000 ms). Trained research assistants confirmed participants’ comprehension of the task and the anchors (i.e. “on purpose, “by accident”). Participants completed 12 practice trials, 12 trials with low time pressure, and 12 trials with high time pressure. Raw scores were totaled as the proportion of “on purpose” responses out of all responses provided.

Intentionality likelihood rating (ILR)

Each item on the task includes an associated value that represents the percent of non-clinical respondents that categorized the item as intentional (without time pressure in Rosset, 2008). We used this untimed, non-clinical response as an estimate of the normative response to each item. In other words, we defined the values as criterion values of how the individual would be expected to respond with normative functioning under normal circumstances. We refer to these values as “intentionality likelihood ratings” (ILR; p. 774, Rosset, 2008).

Process dissociation procedure

Process dissociation (PDP; Jacoby et al., 1993) is an algebraic procedure that allows estimates for the automatic and controlled processes that underlie quick judgments. Automatic processes indicate a bias toward responding a certain way (i.e., intentional or accidental), whereas controlled processes allow individuals to “produce a particular response when they intend to, but not produce the response when they intend not to” (p. 183, Payne, 2001). We were able to dissociate automatic and controlled processes because the intentionality bias task included both congruent trials, in which automatic and controlled processes lead to the same answer (i.e., prototypically intentional actions, as determined by normative data from Rosset [2008]), and incongruent trials, in which automatic and controlled processes lead to different answers (i.e., prototypically accidental actions, determined by the same normative data).

The probability of identifying a congruent condition as intentional is quantified as the expression of control probability, C, and the probability of automatic response occurring with the failure of control, A(1 − C):

In incongruent conditions, however, the participant attempts to make a judgment wherein their automatic response (to see intentionality) and controlled response (the item was rated only by 25% of untimed participants as intentional) are in conflict. In this situation, the likelihood that the participant will identify the item as intentional is the probability of the expression of the automatic bias where there exists the failure of control, A(1 − C):

Based on these assumptions, one can calculate separate estimates of controlled and automatic responding. Control estimates are defined as the difference between identifying the target in congruent (i.e. “correct”) conditions and incongruent (i.e. “incorrect”) conditions:

Finally, with these conditions, one can solve for the automatic bias estimate as well:

Thus, according to this paradigm, two parameters underlie performance on a task involving such binary judgments, controlled processes (PDP Control), which represent modulation of intention to correctly process the stimulus, and automatic processes (PDP Automatic), which represent an automatic preference to regard items as intentional. Thus, it is expected that with reduced ability for an individual to recruit controlled processes (as in the fast condition in the current study), automatic preferences will have a greater effect on the response. See Appendix A for more psychometric details about the calculated estimates of controlled and automatic procesess.

Psychiatric symptoms

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay et al., 1987) is a 30-item interview-based measure of positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, as well as general psychopathology symptoms. These interviews were conducted and rated by experienced research assistants who were trained to achieve adequate reliability (ICC > .80 with a gold standard rater). In the present study, we generated the five-factor solution subscales proposed by Bell and colleagues (1994): cognitive, emotional discomfort, hostility, positive, and negative symptoms, along with the specific item related to suspiciousness/persecution symptoms.

Neurocognition

The MATRICS neurocognitive battery (Nuechterlein et al., 2008) for individuals with schizophrenia was used in discriminant validity analyses. The subtests used in the final validation study phase of SCOPE (Pinkham et al., 2017) – Trails A, Symbol Coding, HVLT-R, Letter Number Span, and Animal Naming – were combined by aggregating z-scores.

Social cognitive skills

Those tasks classified as acceptable (either with or without modifications) from the previous phase of SCOPE (Pinkham et al., 2016) were used to assess social cognitive skills. This five measure battery included assessments of emotion perception (The Penn Emotion Recognition Task [ER-40; Kohler et al., 2003], The Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task [BLERT; Bryson, Bell, & Lysaker, 1997]), and theory of mind (The Reading the Mind in the Eyes Task [Baron-Cohen et al., 2001]; The Hinting Task [Corcoran, Mercer & Frith, 1995]; The Awareness of Social Inference Test - Social Inference: Enriched [TASIT, McDonald et al., 2004]).

Paranoia

The Persecution and Deservedness Scale (Melo et al., 2009) is a 10-item self-report scale designed to assess paranoia and perceived deservedness of persecution. Items describe traits or behaviors related to paranoia to which participants respond with a Likert scale response (scale 0 to 4) identifying the extent to which they identify with each item as well as a follow up item with the same scale identifying the extent to which they feel they deserve the reported persecution. This is designed to distinguish between bad me (depressive type) and poor me (non-affective psychosis type) paranoia in schizophrenia (Melo et al., 2009), though we did not explore this distinction in the current study. Scores range from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating higher levels of paranoia.

Trait hostility

The Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5, Krueger et al., 2012) is a 220-item self-report questionnaire evaluating potentially pathological personality dimensions related to DSM-5 disorders. Items consist of statements related to behaviors or personality dimensions and Likert scale (0 to 3) responses for participants. In the present study, participants completed the ten items related to the Hostility Scale of the PID-5 (PID-5-HS). Total scores thus ranged from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater hostility.

Observed hostility

The Observable Social Cognition: A Rating Scale (OSCARS; Healey et al., 2015) is a rating scale of the participant’s performance in a number of arenas related to social cognition, such as correctly understanding others’ intentions and jumping to conclusions. There are eight items with accompanying Likert scale responses (1 = no evidence of difficulty to 7 = evidence of extreme difficulty). In the present study, we used the informant-rated hostility item, which assesses whether the individual has difficulty “interpreting social interactions in a malevolent or hostile manner.” Participants identified informants before the study; these informants were high contact clinicians, family members, or close friends (i.e. on average spending 4 hours per week with the person).

Role functioning

The Specific Levels of Functioning Scale (SLOF; Schneider & Struening, 1983) is a 31-item informant-rated measure of social functioning, community functioning, and effectiveness in activities of daily living. The present study examined the social acceptability subscale in particular, which includes the following items: regularly arguing with others, having physical fights with others, destroying property, physically abusing self, being fearful/crying/clinging, and taking property from others without permission. Ratings on the SLOF are made on a Likert scale as well (1 to 5, with higher scores indicating better functioning). Informants were the same as those selected for collection of the OSCARS.

Functional capacity

The UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment (UPSA; Patterson et al., 2001) assesses functional capacity with a collection of simulated tasks of daily living; scores range on the UPSA from 0 to 100.

Social skills

The Social Skills Performance Assessment (SSPA; Patterson et al, 2001) is an observer-rated assessment of social skill performance in two three-minute role-play conversations with a confederate. First, the participant is instructed to role-play a conversation with a new neighbor who has just moved to the area and second, to role-play a conversation with a landlord who had failed to fix a leak in the participant’s house. The SSPA evaluates interest, speech fluency, clarity, focus, affect, social appropriateness, submissiveness/persistence, negotiation ability, and overall effectiveness with scores summed and averaged into an overall score (ranging from 1 to 5). Data were coded by an expert rater, and average scores were calculated across both role-plays for the current study.

Procedure

Experienced graduate-level and professional staff conducted all interview-based measures. These research assistants had previous experience working with participants with schizophrenia and completed cross-site training to reliably administer measures and code responses. Data collection took place across two study visits that were separated by an interval of 2 to 4 weeks. All variables reported here include only data from the initial study visit. Because of informant response rates, the sample for all analyses involving the SLOF and OSCARS (all conducted only in the schizophrenia group) were smaller than the full sample (n = 132 and n = 130). Initially, the fast and slow conditions of the IBT were counterbalanced (n = 75 participants with schizophrenia, n = 5 controls). However, due to investigator concern that the fast condition caused participants to continue responding quickly in the slow condition, counterbalancing was discontinued and all participants began with the slow condition. Follow up analyses revealed no significant differences between counterbalanced and non-counterbalanced individuals in IBT total score, automatic or control estimates in either condition or combined conditions. Consistent with Pinkham et al. (2017), participants were excluded from analyses examining relationships to outcomes if they were outliers regarding missing items (+/− 3 SD). At baseline, the mean number of missing responses for the non-patient control group was 1.95 (SD = 3.47) and the schizophrenia group was 3.50 (SD = 3.47).

Data Analytic Plan

Demographics

To examine demographic characteristics of our sample, we compared participants in the schizophrenia group and non-patient controls in the following variables: age, education, parent education, gender and race using independent samples t-tests.

Group differences

First, for analyses related to group differences, we fit a multilevel model with trials nested within participants. The IBT requires the participant to give a binary response to every single item. The present analysis examines the effects of group, time pressure, and the inherent likelihood ratings (ILR) of each item. The baseline values are particularly important, given the fact that each item elicits a different baseline response (i.e. how likely it is that the individual will judge each item to be an intentional action performed by the hypothetical target). These baseline values were drawn from previous research on the intentionality bias (Rosset et al., 2008). Examining the impact of group on the slope of the relationship of ILR to participant response provides information about to what extent each group’s pattern of responding adheres to normative responding as collected through pilot data. We entered the ILR and time pressure manipulation (2400ms, 5000ms) as level 1 predictors and entered group (Schizophrenia, Control) as level 2 predictors.

Automatic and controlled processing estimates

To examine the separate contributions of automatic and controlled processing to participant responses across experimental groups, we conducted a mixed model two-way ANOVA examining main effects of group and time pressure condition, as well as the group by time pressure interaction. This approach allows for examination of the extent to which each group relies on each process, how much each process is recruited in each condition, and the extent to which the time pressure manipulation affects each group with regard to controlled and automatic processing.

Item characteristics

Given previous results from psychometric reviews of attribution meausres in schizophrenia (Buck et al., 2017), we examined the impact of item characteristics to determine which situational contexts elicit the greatest group differences (i.e., clearly accidental, clearly intentional, or ambiguous items). To examine this interaction, we tested the main effect of group on the slope of ILR’s prediction of participant response. A significant interaction would demonstrate that experimental groups differed with regard to their adherence to normative responding across situational contexts.

Relationships to symptoms, social cognitive skills and functional outcomes

To examine other psychometric characteristics, we used intentionality bias total scores (i.e., % items with “on purpose” response), as well as automatic and controlled estimates, to predict measurements of symptoms, neurocognition, and functional outcomes. Consistent with prior research on social cognitive biases in schizophrenia (Buck et al., 2017), we broke these outcomes down into criterion outcomes (i.e. paranoia, hostility, interpersonal conflict) – or those expected to be related to social cognitive biases, and general functional outcomes (i.e., general social functioning and role functioning) – or those that are important to assess in schizophrenia, but are generally more closely related to social cognitive skills.

Results

Demographics

Groups differed on only one demographic characteristic: Controls completed significantly more years of school than the schizophrenia group. All demographic analyses are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and tests for differences between the schizophrenia and non-clinical control samples.

| Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| SCZ (n = 213) |

Control (n =151) |

Effect | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 41.69 (11.73) | 42.28 (12.30) | ||

| Education (years) | 13.04 (2.51) | 14.20 (1.91) | *** | |

| Estimated Mother’s Education | 13.39 (3.62) | 13.27 (2.86) | ||

| Estimated Father’s Education | 13.54 (4.21) | 13.62 (3.15) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 138 (64.79%) | 95 (62.91%) | ||

| Female | 75 (35.21%) | 56 (37.09%) | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 114 (53.52%) | 80 (52.98%) | ||

| Black | 84 (39.43 %) | 60 (39.74%) | ||

| Am. Indian / Pacific Islander | 3 (1.41%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| Asian | 5 (2.35%) | 4 (2.65%) | ||

| Other | 7 (3.29%) | 7 (4.64%) | ||

| IBT Total (% intentional) | 0.40 (0.15) | 0.44 (0.18) | * | |

| IBT Automatic | 0.41 (0.27) | 0.34 (0.23) | ** | |

| IBT Control | 0.28 (0.24) | 0.38 (0.24) | *** | |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p<.001

Group Differences

We first tested whether individuals with schizophrenia demonstrated an elevated bias toward intentionality. A multilevel model predicting intentional responses by ILR, time pressure, and group revealed a main effect of group, F(1,7835) = 6.00, p < .014. At the mean ILR rating, individuals in the schizophrenia group (M = 0.43, 95% CI [0.41, 0.46]) were more likely to identify items as intentional than the control group (M = 0.38, 95% CI [0.35, 0.41]). Second, we tested the same full model as described above for a (1) a main effect of time pressure (expecting higher scores in high-time pressure) as well as (2) a two-way group by time pressure interaction (expecting greatest group differences in low time pressure condition), to examine our hypothesis that individuals with schizophrenia will be differentially affected by the time pressure manipulation relative to controls. There was no main effect of the time pressure manipulation, F(1,7835) = .73, p = .40. There was also no significant time pressure by group interaction, F(1,7835) = .37, p = .54, indicating that the rate of intentionality judgments of individuals in the schizophrenia sample were not differentially affected by the time pressure manipulation.

Automatic and Controlled Processing Estimates

To better understand why participants with schizophrenia are more likely to perceive intentionality, we examined the automatic and control estimates derived from the process dissociation procedure. A mixed ANOVA predicting control estimates by time pressure and group revealed a main effect of group, η2p = .04, F(1, 351) = 13.48, p < .001, such that individuals with schizophrenia demonstrated lower control estimates (M = .28) than healthy participants (M = .38) across both conditions, as well as a main effect of time pressure, η2p = .12, F(1, 351) = 47.24, p < .001, such that all participants demonstrated lower control in the fast condition than the slow condition. We found no time pressure by group interaction, η2p = .00, F(1, 351) = 0.95, p = .33.

As predicted, a mixed ANOVA predicting automatic estimates by time pressure and group also revealed a main effect of group, η2p = .02. F(1, 354) = 6.78, p = .01, such that participants with schizophrenia demonstrated a higher automatic bias for perceiving intentionality (M = .41) compared to control participants (M = .34). We found no effect of time pressure condition on automatic estimates, η2p = .01, F(1, 354) = 1.67, p = .20, and no group by time pressure interaction, η2p = .00, F(1, 354) = 0.02, p = .89. These results point to two conclusions: one, participants with schizophrenia showed a higher automatic preference for perceiving intentionality, and two, they showed less ability to effortfully control their responses.

Item Characteristics

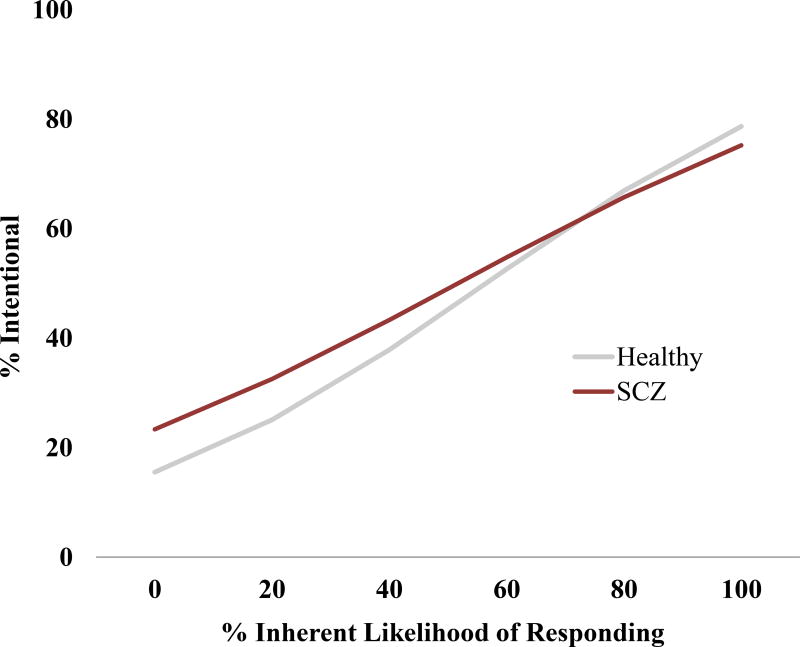

The process dissociation findings allowed a lens to examine components of the tendency of participants with schizophrenia to perceive intentionality. We next analyzed whether these participants showed a greater tendency to perceive intentionality for specific items. To this end, we found an significant interaction between group and ILR, F(1, 7835) = 20.82, p < .001, such that group differences in perceived intentionality were highest for items with low ILR ratings (i.e., prototypically accidental items). This interaction suggests that individuals with schizophrenia are most biased in response to items that are less normatively regarded as intentional (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparing responses (in logistic regression) in the schizophrenia and control groups graphed as a function of inherent likelihood of responding for the Intentionality Bias Task (IBT) combined across time condition.

Relationships to Psychiatric Symptoms

IBT total scores, as well as automatic and controlled estimates from process dissociation, were unrelated to psychiatric symptoms, as assessed in PANSS interviews (Table 2).

Table 2.

Psychometric examination of the intentionality bias task.

| Intentionality Bias (IBT) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Total Score |

PDP Automatic |

PDP Control |

|

| Neurocognition | |||

| MATRICS Composite | −.08 | −.10 | .30*** |

| Psychiatric symptoms | |||

| PANSS Cognitive | .03 | .02 | −.08 |

| PANSS Emotional Distress | .13 | .09 | .04 |

| PANSS Hostility | .04 | .03 | −.06 |

| PANSS Negative | −.03 | −.07 | −.01 |

| PANSS Positive | −.06 | −.08 | .00 |

| Social cognition skills | |||

| BLERT | −.11 | −.09 | .32*** |

| ER-40 | −.17* | −.14* | .33*** |

| Eyes | −.13 | −.11 | .38*** |

| Hinting Test | −.10 | −.10 | .17* |

| TASIT Total | −.04 | −.07 | .31*** |

| Functional outcomes | |||

| Criterion outcomes | |||

| PID5 Hostility Scale | .16* | .11 | −.05 |

| PADS Persecution | .08 | .06 | .09 |

| SLOF Social Acceptability | −.16 | −.13 | −.04 |

| OSCARS Hostility Item | .15 | .11 | −.03 |

| General outcomes | |||

| SLOF – Total | −.19* | −.16 | −.03 |

| SSPA – Total | −.14* | −.14 | .20** |

| UPSA – Total | −.19* | −.19** | .22** |

Note: For analyses involving an informant (OSCARS, SLOF), a subset of the sample is included for whom informants responded to requests for information (n = 130, 132).

p < .001,

p < .01,

p ≤ .05,

p < .10

Relationships to Social Cognitive Skills

While control estimates were positively correlated with all five SCOPE measures of social cognitive skill, automatic bias estimates and total scores were significantly negatively related with one measure of emotion perception (the ER-40). These patterns suggest that an increased ability to control responses on the IBT is related to social cognitive skill, and an overall tendency to see more intentionality may be related to emotion perception (Table 2).

Relationships to Functional Outcomes

The IBT total score was related to a number of the criterion functional outcomes; higher levels of intentionality bias correlated only with increased trait hostility. Neither automatic nor control estimates were independently related to these outcomes (Table 2).

The IBT was related to a number of general social and role functioning outcomes, as total scores correlated with role functioning, social functioning, and functional capacity; automatic estimates negatively correlated with functional capacity, while the control estimate was positively related to social skills and independent living skills (Table 2).

Discussion

Overall, the present study extends research demonstrating that individuals with schizophrenia make aberrant judgments of others’ intentions. This bias toward attributing intentionality (1) is elevated in schizophrenia, with greater elevation for actions that are normatively regarded as accidental, (2) differs from healthy controls in both automatic and controlled components, (3) relates to hostility, role functioning, social functioning, and functional capacity. Additionally, reliance on controlled processes was affected by the time pressure manipulation in both groups, such that all participants’ responses become more inaccurate under pressure.

Our schizophrenia sample was more likely to see others’ actions as intentional (relative to controls), in line with previous work (Combs et al., 2007, 2013; Moritz et al., 2007; Peyroux et al., 2014). Furthermore, individuals with schizophrenia showed both diminished cognitive control and increased automatic bias (Jacoby, 1991; Payne, 2001). In other words, individuals with schizophrenia were less apt to control their judgments; and, when they failed to control their judgments, they were more likely to to present with an automatic bias to interpret others’ actions as intentional. These results support our hypothesis that the increased rate of intentionality judgments in schizophrenia is a result of group differences in two different cognitive processes.

Furthermore, when participants in both groups were subjected to time pressure, they were less able to engage in controlled processing, leading to increased expression of automatic bias. One implication of this finding is that healthy controls placed under time pressure closely resemble participants with schizophrenia who are not under time pressure. In this way, environmental factors can cause healthy controls’ judgments of intentionality to align more closely with judgments typical of people with schizophrenia. This finding provides additional support for the view that dual processes underlying intentionality judgments might be relevant in schizophrenia.

Additionally, our results suggest that the least prototypically-intentional items produced the greatest group differences. In other words, individuals with schizophrenia were especially likely, compared to controls, to attribute intentionality for events that are paradigmatically accidental. This finding is consistent with recent suggestions that the abbreviation of attributional style measures to include only ambiguous events (as in the AIHQ) may be misguided, and that accidental/non-intentional items should be included as well (Buck et al., 2017). Ambiguous events appear to elicit patterns that are correlated with paranoia in non-clinical samples (Combs et al., 2007); in schizophrenia, however, it appears that neutral or apparently accidental situations may elicit the greatest group differences. This intentionality bias did not relate to psychiatric symptoms. The ability to control judgments of intentionality on the IBT was positively related with an array of social cognitive skills, while some social cognitive skills (i.e. emotion perception and theory of mind) were negatively related to the general bias toward intentionality. The IBT showed some significant – albeit small – relationships to a number of criterion and general functional outcomes, including trait hostility, functional capacity, as well as role and social functioning. Interestingly, one key relationship with a criterion outcome (i.e. trait hostility) appeared inconsistent with the lack of relationships to clinician-rated symptoms (as in the case of hostility symptoms). This might indicate that the IBT is connected to more subtle or dispositional cognitive characteristics, rather than overt symptoms.

As an instrument for clinical trials, the IBT is not without psychometric limitations. As demonstrated here, the IBT has suboptimal test-retest reliability (reflected in the control and automatic estimates), and its correlations with both general and criterion outcomes are significant but are relatively small. Further, the IBT did not demonstrate an expected relationship to paranoia. Given these findings, the present study does not provide support for the use of the IBT as a measurement in clinical trials, consistent with the conclusions of SCOPE (Pinkham et al., 2017). Future research and additional pilot testing should reveal whether these findings are the product of scale limitations, attributions being a state (rather than trait) characteristic, or other issues with our proposed model of biased social judgments. Similar to early examinations of other innovative assessments tested in schizophrenia samples (i.e. Social Attribution Test – Multiple Choice [SAT-MC], Bell et al., 2010; self-referential memory and biological motion tasks; Kern et al., 2013), the IBT may provide useful insights broadly, but requires adaptation before use in clinical trials. In spite of the psychometric limitations of the IBT, the present study has important implications for the study of cognitive biases in schizophrenia. First, it presents a new paradigm – employing time pressure paradigms and process dissociation – for the study of attribution biases. These tools distinguish impairments in the ability to understand situational cues from straightforward biases. Second, the methodology of the IBT also provides a model for how performance on intentionality bias task measures can provide comparisons to normative responding in the item level (i.e. ILR). Finally, it provides useful theoretical insights about the bias toward intentionality in schizophrenia. These findings suggest that individuals with schizophrenia differ in how they attribute intentionality broadly, rather than only in negative or threatening situations.

A few study limitations deserve mention. First, controlled laboratory paradigms are removed from day-to-day life, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Also, though the present study examines improvements in measurement of attribution bias, an existing measure of this construct (i.e., the AIHQ) was not collected with this sample for comparison. However, given that questions have been raised about an abbreviated AIHQ (Buck et al., 2017), relationships to symptoms and functioning can also be appropriate outcomes to examine for convergent validity. Second, given a lack of pilot testing for this task, it might be the case that the slow (5000 ms) condition was still too fast for individuals in the schizophrenia group, given well-documented impairments in neurocognition. This is particularly a concern given the presence of missing data on some trials. However, with the exception of a small number of participants who failed to complete the task, the majority of participants were able to successfully complete the task in the presence of a graduate-level research assistant.

While these limitations should prompt caution in interpretation, the IBT provides an important first step in developing a process model of attributions of intentionality in schizophrenia. Participants with schizophrenia differ from controls in both the automatic and controlled processes that aid in making such judgments, and metrics approximating these values are also related to general functional outcomes. Further, the automatic bias of individuals with schizophrenia to see intentionality in all situations may become more impactful on behavior, given additional findings in the current study that all participants are less able to recruit controlled processes in such judgments when pressured. This follows previous results suggesting that the final judgment is an informative predictor of functional outcomes (Pinkham et al., 2017), but also that individuals with schizophrenia may differ from healthy controls with regard to their metacognitive self-assessment or effort allocation (Cornacchio et al., 2017).

Future work might consider the origin of the observed group differences in intentionality bias. For example, patients who have received ongoing treatment for schizophrenia might receive considerable social feedback that even seemingly accidental movements, gestures, and statements nevertheless have diagnostic meaning and some underlying “cause” or intention; this type of environment might condition patients to perceive acts as intentional. The underlying social causes (if any) might be further addressed by considering the relationship between subclinical schizotypy and intentionality bias. Such a comparison would account for potential explanatory variables such as clinical environmental influences, side effects of medication, and illness. Finally, the present research demonstrates the potential for social and cognitive psychological paradigms to improve future clinical measurement of social cognition.

Broadly, the present work highlights the importance of considering differences in schizophrenia in the context of the “normal” biases shown in subclinical populations, rather than thinking of these biases as “present” in populations with schizophrenia and “absent” from normative populations. For example, most people show some degree of intentionality bias, and doing so may not be an issue. However, problems may arise for those with schizophrenia because they show an amplified bias for intentionality, or because they have trouble controlling this bias. Other domains that are aberrant among people with schizophrenia, such as hostile attributions, emotion perception deficits, and/or threat sensitivity, may also be meaningfully considered as more powerful or uncontrollable versions of biases that most people possess to some extent. By understanding symptoms of schizophrenia as a matter of degree, rather than kind, we can better understand these symptoms by drawing on work from other areas, such as social and cognitive psychology. In this way, some of the greatest future insights into schizophrenia and other psychopathology may come from combining clinical insight with research on general human tendencies.

Supplementary Material

General Scientific Summary.

Individuals with schizophrenia present with an aberrant tendency to regard others’ actions as intentional and hostile. Given limitations of previous measures, it is unclear whether (1) schizophrenia is associated with aberrant judgments of intentionality regardless of valence, or if this social cognitive bias is the product of an automatic bias (i.e. immediate preference) diminished control (i.e. inaccurate responding), or a combination of both. This study supports a dual process model of intentionality in schizophrenia, indicating that individuals with schizophrenia both differ from controls in automatic bias, controlled processing, and these differences impact general and conflict-related functional outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the individuals who participated in this study and the following individuals for their assistance with data collection and management: Grant Hardaway (UTD), Katie Kemp (UTD), Lana Nye (UNC), Grace Lee Simmons (UNC), Sara Kaplan (UM), and Craig Winter (UM). Data analyses were completed (and their accuracy is certified by) Benjamin Buck and Neil Hester.

References

- Abramson LY, Seligman ME, Teasdale JD. Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1978;87(1):49–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DN, Strauss GP, Donohue B, van Kammen DP. Factor analytic support for social cognition as a separable cognitive domain in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;93(1):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An SK, Kang JI, Park JY, Kim KR, Lee SY, Lee E. Attribution bias in ultra-high risk for psychosis and first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;118:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MD, Fiszdon JM, Greig TC, Wexler BE. Social attribution test—multiple choice (SAT-MC) in schizophrenia: comparison with community sample and relationship to neurocognitive, social cognitive and symptom measures. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;122(1):164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellack AS, Sayers M, Mueser KT, Bennett M. Evaluation of social problem solving in schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:371–378. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck B, Healey KM, Gagen EC, Roberts DL, Penn DL. Social cognition in schizophrenia; Factor structure, clinical and functional correlates. Journal of Mental Health. 2015 doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1124397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken S, Trope Y. Dual-process theories in social psychology. Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Combs DR, Penn DL. The role of subclinical paranoia on social perception and behavior. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;69(1):93–104. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs DR, Penn DL, Cassisi J, Michael C, Wood T, Wanner J, Adams S. Perceived racism as a predictor of paranoia among African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006;32(1):87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Combs D, Penn D, Wicher M, Waldheter E. The ambiguous intentions hostility questionnaire (AIHQ): A new measure for evaluating hostile social-cognitive biases in paranoia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2007;12(2):128–143. doi: 10.1080/13546800600787854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs D, Penn D, Michael C, Basso M, Wiedeman R, Siebenmorgan M, Tiegreen J, Chapman D. Perceptions of hostility by persons with and without persecutory delusions. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2009;14(1):30–52. doi: 10.1080/13546800902732970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornacchio D, Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Harvey PD. Self-assessment of social cognitive ability in individuals with schizophrenia: Appraising task difficulty and allocation of effort. Schizophrenia Research. 2017;179(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL. The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: a review. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(S1):44–63. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egloff B, Schwerdtfeger A, Schmukle SC. Temporal stability of the implicit association test-anxiety. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2005;84(1):82–88. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8401_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elnakeeb M, Abdel-Dayem S, Gaafar M, Mavundla T. Attributional style of Egyptians with schizophrenia. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2010;19:445–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Patient Edition. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Penn DL, Bentall R, et al. Social cognition in schizophrenia: an NIMH workshop on definitions, assessment, and research opportunities. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34:1211–1220. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris ST, Oakley C, Picchioni MM. A systematic review of the association between attributional bias/interpersonal style, and violence in schizophrenia/psychosis. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2014;19(3):235–241. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12(3):426. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Kern RS, Shokat-Fadai K, Sergi MJ, Wynn JK, Green MF. Social Cognitive Skills Training in schizophrenia: an initial efficacy study of stabilized outpatients. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;107:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon IH, Kim KR, Kim HH, et al. Attributional Style in Healthy Persons: Its Association with Theory of Mind Skills. Psychiatry Investigation. 2013;10(1):34–40. doi: 10.4306/pi.2013.10.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern RS, Penn DL, Lee J, et al. Adapting social neuroscience measures for schizophrenia clinical trials, part 2: Trolling the depths of psychometric properties. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2013;39(6):1201–1210. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinderman P, Bentall RP. Causal attributions in paranoia: Internal, personal and situational attributions for negative events. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:341–345. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz MM, Richardson CL. Social cognitive training for schizophrenia: a meta-analytic investigation of controlled research. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;38(5):1092–1104. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J. Manual for the Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale 1986 [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso F, Horan W, Kern R, Green M. Social cognition in psychosis: Multidimensional structure, clinical correlates, and relationship with functional outcome. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;125(2–3):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta UM, Bhagyavathi HD, Thirthalli J, Kumar KJ, Gangadhar BN. Neurocognitive predictors of social cognition in remitted schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2014;219(2):268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay R, Langdon R, Coltheart M. Jumping to conclusions? Paranoia, probabilistic reasoning, and need for closure. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2007;12:362–376. doi: 10.1080/13546800701203769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPheeters HL. Statewide mental health outcome evaluation: A perspective of two southern states. Community Mental Health Journal. 1984;20:44–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00754103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Moscona S, McKibbin CL, Davidson K, Jeste DV. Social skills performance assessment among older patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2001;48(2):351–360. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD performance-based skills assessment: Development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001;27(2):235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne BK. Prejudice and perception: The role of automatic and controlled processes in misperceiving a weapon. Journal of personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81(2):181–192. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham A, Penn D, Green M, Buck B, Healey K, Harvey P. The social cognition psychometric evaluation study: Results of the expert survey and rand panel. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2013;39(5):1–11. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Green MF, Harvey PD. Social Cognition Psychometric Evaluation (SCOPE): Results of the initial psychometric study. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2015;42(2):494–504. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosset E. It’s no accident: Our bias for intentional explanations. Cognition. 2008;108(3):771–780. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savla GN, Vella L, Armstrong CC, Penn DL, Twamley EW. Deficits in domains of social cognition in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2013;39(5):979–992. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney PD, Anderson K, Bailey S. Attributional style in depression: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50(5):974–992. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hooren S, Versmissen D, Janssen I, Myin-Germeys I, à Campo J, Mengelers R, van Os J, Krabbendam L. Social cognition and neurocognition as independent domains in psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2008;103(1):257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J, Green MF, Shaner A, Liberman RP. Training and quality assurance with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: “the drift busters”. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1994;3:221–244. [Google Scholar]

- Waldheter E, Jones N, Johnson E, Penn D. Utility of social cognition and insight in the prediction of inpatient violence among individuals with a severe mental illness. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193(9):609–618. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000177788.25357.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens AN, Bryan JE, Crossen JR. Estimating WAIS-R FSIQ from the national adult reading test-revised in normal subjects. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1993;7(1):70–84. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.