Abstract

Different Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains are simultaneously or in succession involved in spontaneous wine fermentations. In general, few strains occur at percentages higher than 50% of the total yeast isolates (predominant strains), while a variable number of other strains are present at percentages much lower (secondary strains). Since S. cerevisiae strains participating in alcoholic fermentations may differently affect the chemical and sensory qualities of resulting wines, it is of great importance to assess whether the predominant strains possess a “dominant character.” Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate whether the predominance of some S. cerevisiae strains results from a better adaptation capability (fitness advantage) to the main stress factors of oenological interest: ethanol and temperature. Predominant and secondary S. cerevisiae strains from different wineries were used to evaluate the individual effect of increasing ethanol concentrations (0-3-5 and 7% v/v) as well as the combined effects of different ethanol concentrations (0-3-5 and 7% v/v) at different temperature (25–30 and 35°C) on yeast growth. For all the assays, the lag phase period, the maximum specific growth rate (μmax) and the maximum cell densities were estimated. In addition, the fitness advantage between the predominant and secondary strains was calculated. The findings pointed out that all the predominant strains showed significantly higher μmax and/or lower lag phase values at all tested conditions. Hence, S. cerevisiae strains that occur at higher percentages in spontaneous alcoholic fermentations are more competitive, possibly because of their higher capability to fit the progressively changing environmental conditions in terms of ethanol concentrations and temperature.

Keywords: Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains, spontaneous wine fermentation, fitness advantage, temperature, ethanol

Introduction

Spontaneous grape juice fermentation into wine is carried out by the yeast populations naturally occurring on the grape surface and in the winery environment (Sabate et al., 2002; Bisson, 2012). In this process, in the vats filled at the beginning of the vintage, non-Saccharomyces yeast species usually predominate in the early stages and later, with ethanol increasing, they are replaced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae because of higher resistance of this yeast species to alcohol (Pretorius, 2000; Bisson, 2005; Querol and Fleet, 2006; Albergaria and Arneborg, 2016). This substitution may be explained by the competitive exclusion of the less efficient yeasts species (Arroyo-López et al., 2011). Although ethanol production has been the cause traditionally accepted for explaining the imposition of S. cerevisiae on non-Saccharomyces yeast species, other death-inducing mechanisms have been proposed as responsible for its competitive advantage, including the production of antimicrobial compounds, such as SO2 and peptides, the cell-to-cell contact, and the temperature increase during alcoholic fermentation (Goddard, 2008; Salvadó et al., 2011; Perrone et al., 2013; Branco et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2015; Albergaria and Arneborg, 2016; Pérez-Torrado et al., 2017). Therefore, as the fermentation progresses, the grape must becomes a more selective environment representing a highly specialized ecological niche (Salvadó et al., 2011). Nevertheless, S. cerevisiae populations generally display a high polymorphism in spontaneous wine fermentations. Indeed, numerous studies, carried out by molecular techniques on the population dynamics of S. cerevisiae during spontaneous wine fermentations in several regions all over the world, have established that different strains are simultaneously or in succession involved during the whole fermentation process (Querol et al., 1994; Pramateftaki et al., 2000; Augruso et al., 2005; Schuller et al., 2005; Agnolucci et al., 2007; Csoma et al., 2010; Orlić et al., 2010; Capece et al., 2011, 2012; Mercado et al., 2011; Bisson, 2012). In some cases S. cerevisiae strains were able to dominate the alcoholic fermentation in all vats of the same winery, independently of the grapevine cultivar (Frezier and Dubourdieu, 1992; Guillamón et al., 1996), whereas other times the yeast strains were found to be specific for each grape variety (Blanco et al., 2006). In general, few S. cerevisiae strains occur at higher percentages (more than 30–50% of the total yeast isolates) while a variable number of strains are present at lower percentages. Therefore, these strains can be differentiated in “predominant” and “secondary” strains, respectively (Versavaud et al., 1995). In addition, the predominant strains can sometimes persist in alcoholic fermentations carried out in the same winery in consecutive years and can be described as “recurring” strains (Gutièrrez et al., 1999; Bisson, 2012). Since S. cerevisiae strains, participating in alcoholic fermentations, may differently affect the chemical and sensory qualities of resulting wines (Fleet, 2003; Romano et al., 2003; Villanova and Sieiro, 2006; Lopandic et al., 2007; Barrajón et al., 2011; Knight et al., 2015; Bokulich et al., 2016; Callejon et al., 2016), it is of great importance to assess whether the predominant strains retain the dominant behavior after their isolation from grape must fermentations. Furthermore, it could be noteworthy to investigate whether the predominance of these S. cerevisiae strains on others results from a different adaptation capability (fitness advantage) to some stress factors of oenological interest. Recently, two studies concerning competition between strains of S. cerevisiae species suggest that the dominance of one strain over another is dependent on the different SO2 production and resistance and on the cell-to-cell contact in mixed cultures, i.e., in the same environment (Perrone et al., 2013; Pérez-Torrado et al., 2017). With the exception of studies on killer factors (Jacobs and van Vuuren, 1991; Pérez et al., 2001), to our knowledge, other surveys on the competition among strains of S. cerevisiae species are lacking. Considering that temperature and ethanol during alcoholic fermentation are held responsible for the ability of S. cerevisiae to dominate on non-Saccharomyces yeasts or on other Saccharomyces spp. (Goddard, 2008; Williams et al., 2015; Alonso del-Real et al., 2017; Henriques et al., 2018), the adaptability to these two factors could be also involved in determining the dominance of predominant on secondary S. cerevisiae strains. Moreover, the predominance of S. cerevisiae strains with particular resistance capability to these two stress factors could contribute to the construction of an ecological niche typical of each fermentation tank and possibly winery.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate whether the predominance of some S. cerevisiae strains during spontaneous alcoholic fermentation results from a better adaptation capability of these strains to ethanol and temperature as stress factors. At first, dynamics of S. cerevisiae strains during spontaneous wine fermentations carried out in six Tuscan wineries were monitored to identify one predominant and one secondary S. cerevisiae strains from each winery. After that, the predominant and secondary strains of each winery were tested in synthetic media to compare their growth capability when subjected to stress of ethanol and temperature. Finally, the fitness advantage (as defined by Salvadó et al., 2011) was calculated to verify if the predominant strains owned a better adaptation capability than the secondary strains to the two main stress factors of oenological interest.

Methods

Isolation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae from spontaneous wine fermentations

Spontaneous wine fermentations were carried out under industrial conditions during the same vintage in six wineries (A, B, C, D, E, and F) producing DOC and DOCG red wines in Tuscany region (Central Italy). In all the winery except the E, commercial starter yeasts were never used. In each winery, various fermentation tanks (6 in winery A; 2 in B; 8 in C; 6 in D; 4 in E; 6 in F) were filled with musts from different grape varieties (S: Sangiovese; CA: Cabernet; N: Pinot Nero; M: Merlot; V: Vermentino). Yeasts were isolated by plating the must/wine samples on WL Nutrient Agar medium (Oxoid Ltd, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) containing sodium propionate (2 g/L) and streptomycin (30 mg/L) to inhibit mold and bacterial growth, respectively. Plates were incubated for 48 h at 30°C, under aerobic conditions. S. cerevisiae isolates were identified by PCR-RFLP analysis of the rDNA Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) according to Esteve-Zarzoso et al. (1999).

About 25 isolates from each fermentation tank belonging to S. cerevisiae species were stored in liquid cultures containing 50% (v/v) glycerol at −80°C until use.

Genotypic characterization of S. cerevisiae isolates

Genotypic differentiation of S. cerevisiae isolates was performed by mitochondrial DNA restriction analysis (mtDNA-RFLP) and the restriction endonucleases RsaI and Hinf I (Granchi et al., 2003). The restriction DNA fragments were separated on 0.8%(w/v) agarose gels containing ethidium bromide (1 mg mL−1) by electrophoresis in 1X-TBE buffer (90 mMTris-borate, 2 mM, EDTA pH 8.0) at 4 Vcm−1 for 6 h. The RFLP patterns were submitted to pairwise comparison using the Dice coefficient (SD) (Sneath and Sokal, 1973) and cluster analysis with unweighted pair group method (UPGMA) by Gel Compar 4.0 software (Applied Math, Kortrijk, Belgium). S. cerevisiae diversity in each winery was quantified by using the two indices “H” and “e” as proposed by Shannon–Weaver (Shannon and Weaver, 1963).

Laboratory-scale fermentations to verify the predominance behavior of S. cerevisiae strains

The medium used for laboratory scale fermentation was the chemically defined grape juice medium reported in the Table 1 of the RESOLUTION OIV-OENO 370 (2012). The synthetic medium was buffered to pH 3.3 using HCl 1N and sterilized by filtration. Fermentation experiments were carried out in triplicate in 250-mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 160 mL of the medium. Each flask was inoculated with two S. cerevisiae strains at the same concentration (104 cells mL−1) from pre-cultures grown for 24 h in the same medium. After inoculation, the flasks were sealed with a Müller trap previously filled with sulphuric acid to allow only CO2 to outflow and they were incubated at 28°C. The fermentation progress was followed by determining the weight loss due to CO2 release until the weight remained constant. At the end of fermentation, chemical analysis were performed by HPLC (Schneider et al., 1987; Granchi et al., 1998). Viable counts of the yeasts were performed, after 24 h and 10 days from inoculation, on WL Nutrient Agar medium (Oxoid Ltd, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) incubated 48 h at 30°C in aerobic conditions. To calculate isolation frequencies of the two S. cerevisiae strains inoculated together in the each fermentation flask, a significant number of colonies from WL Nutrient Agar medium were assayed using mtDNA-RFLP as reported above.

Table 1.

Isolation frequencies, expressed as percentages, of mt-DNA profiles of S. cerevisiae from 32 spontaneous wine fermentations carried out in different tanks during the same vintage in six wineries in Tuscany (Italy).

| Sample code | mt-DNA profiles | Isolation frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| AS1 | AIV- AV - AVI - AVII - AXII - AXIII | 46 - 17 - 17 - 4 - 8 - 8 |

| AS2 | AIV - AV - AVI - AVII - AXII - AXIII | 29 - 8 - 21 - 17 - 12.5 - 12.5 |

| AM1 | AI - AIV - AV - AVII - AX - AXII - AXIV | 4 - 4 - 13 - 13 - 36 - 26 - 4 |

| AM2 | AVI - AVII - AX - AXIV | 4 - 12.5 - 79.5 - 4 |

| AP1 | AX - AXI | 90 - 10 |

| AP2 | AIV - AX - AXI - AXII - AXIII | 16.5 - 16.5 - 8.5 - 42 - 16.5 |

| BS1 | BI - BII - BIII - BIV - BVII - BVIII - BIX | 10 - 35 - 5 - 35 - 5 - 5 - 5 |

| BS2 | BII - BIV - BV - BVI - BVII - BVIII - BX BXI - BXII - BXIII - BXIV - BXV - BXVI | 20.2−3.8 - 3.8−15.2 - 11.4−7.6−3.8 3.8 - 15.2 - 3.8 - 3.8 - 3.8 - 3.8 |

| CS1 | CI - CII - CIII - CIV - CVI - CVII | 10 - 5 - 10 - 25 - 5 - 45 |

| CS2 | CI - CII - CIII -CIV - CV - CVII | 10 - 5 - 60 - 5 - 5 - 15 |

| CS3 | CI - CIII - CIV - CV | 10.6 - 73.5 - 10.6 - 5.3 |

| CS4 | CI - CIII | 10 - 90 |

| CM1 | CI - CIII | 10 - 90 |

| CM2 | CI - CIII | 5 - 95 |

| CM3 | CI - CIII | 16 - 84 |

| CM4 | CI - CIII | 5 - 95 |

| DS1 | DI - DIV - DVI - DX | 4.2 - 83.2 - 4.2 - 8.4 |

| DS2 | DIV - DVI - DVII | 69.6 - 17.4 - 13 |

| DS3 | DI - DII - DIV - DVI - DVII - DXI | 12.5 - 4.2 - 41.6 - 12.5 - 25 - 4.2 |

| DS4 | DI - DIII - DIV- DVI -DVII - DVIII | 22.5 - 9 - 32.5 - 13.5−18 - 4.5 |

| DM1 | DI - DII - DIII - DIV - DV | 50 - 5 - 5 - 35 - 5 |

| DM2 | DI - DIII - DIV - DVI - DVII - DIX | 4.25 - 4.25 - 46 - 4.25 - 37 - 4.25 |

| ES1 | EI - EVII | 40 - 60 |

| EC2 | EI - EIII - EVII | 71.5 - 9.5 - 19 |

| EM1 | EI - EII - EIII - EIV - EV - EVI | 68.5 - 14 - 7 - 3.5 - 3.5 - 3.5 |

| EM2 | EI - EIII | 96 - 4 |

| FVN1 | FI - FII - FIII - FIV - FV | 42 - 8 - 8 - 34 - 8 |

| FVN2 | FI - FII - FIV | 60 - 10 - 30 |

| FVN3 | FI - FIII - FIV - FVII - FVIII | 44 - 25 - 19 - 6 - 6 |

| FVB1 | FI - FIII - FIV - FVII | 13.5 - 40 - 40 - 6.5 |

| FVB2 | FI - FIII - FIV | 6.5 - 53.5 - 40 |

| FVB3 | FI - FII - FIII - FIV - FV | 13.5 - 6.5 - 26.5 - 47 - 6.5 |

The sample codes indicate the winery (A, B, C, D, E and F), the grape variety (Sangiovese: S, Cabernet: C, Pinot Nero: P, Merlot: M, Vermentino nero: VN and Vermentino bianco: VB), and the number of the fermentation tank. The predominant S. cerevisiae strains are in bold and underlined.

Effect of ethanol on the S. cerevisiae growth

The medium used to assay the effect of ethanol on the growth of the different S. cerevisiae strains was Yeast Nitrogen Base (Difco) integrated with glucose (20 g L−1) and increasing concentrations of ethanol (0-3-5 and 7% v/v). Fermentation trials were carried out at 28°C in triplicate in 100-mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing synthetic medium (50 mL each flask) inoculated with 2 × 106 cells mL−1 (axenic cultures) from pre-cultures of the various S. cerevisiae strains grown for 24 h in the same medium without ethanol. Fermentation progress was monitored every 2 h quantifying by HPLC sugar degradation (Lefebvre et al., 2002). On the same samples, viable cells were determined by Thoma counting chamber and fluorescence microscopy to monitor the yeast growth as reported by Granchi et al. (2006). The decimal logarithms of viable counts detected during the time course of each fermentation after 8 and 24 h were fitted both to Baranyi and Roberts (1994) function and to reparametrized Gompertz equation proposed by Zwietering et al. (1990) by using Combase-DMfit software and GraphPadPrism 5, respectively. Finally, the area under the growth curve of each strain was calculated as reported by Arroyo-López et al. (2009, 2010) and Castilleja et al. (2017), using GraphPadPrism 5.

Combined effect of ethanol and temperature on S. cerevisiae growth

To evaluate the combined effect of temperature and ethanol on the S. cerevisiae growth, a Box-Wilson Central Composite Design with two variables and three levels was used. The medium used was Yeast Nitrogen Base (Difco) integrated with 20 g mL−1. The range of temperatures was 25–35°C, while the range of ethanol was 0–7% (v/v). As reported in the previous experiment, fermentation progress was monitored every 2 h (for 24 h) quantifying by HPLC the sugar degradation, while the viable yeast cells were determined by Thoma counting chamber and fluorescence microscopy. The decimal logarithms of viable yeast cells detected during the time course of each fermentation were fitted to Gompertz function using GraphPadPrism 5. The area under the growth curve of each strain was calculated using GraphPadPrism 5.

Results

Predominant S. cerevisiae strains in spontaneous wine fermentations

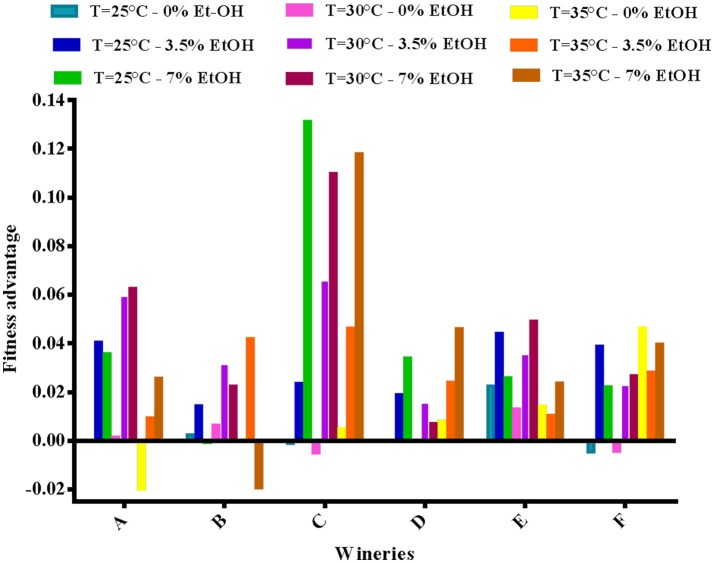

Dynamics of yeasts in spontaneous wine fermentations carried out during the same vintage in six wineries producing DOC and DOCG red wines in Tuscany region (Italy) were monitored. For each winery, from two to eight fermentation tanks were filled with musts obtained from different grape variety (Sangiovese, Cabernet, Pinot Nero, Merlot, Vermentino), and allowed to ferment naturally. When the yeast population reached the maximum growth yield, 637 isolates belonging to S. cerevisiae species (about 25 isolates from each fermentation tank) were analyzed by mitochondrial DNA (mt-DNA) restriction analysis. The mt-DNA profiles obtained for each tank in the different wineries and the relative frequencies of isolation expressed as percentages are reported in table 1. Results revealed that, independently of the winery and the grape variety, each spontaneous wine fermentations was carried out by one or two predominant S. cerevisiae strains at high frequency, ranging from about 30–90%, in association with a variable number of secondary strains at low frequency. Moreover, some predominant strains were shared by different grape varieties fermented in various tanks (Table 1). By calculating the isolation frequency of each different mt-DNA profile occurring in each winery, a total of 58 S. cerevisiae strains out 637 isolates from the six wineries were obtained (Table 2). Then, they were distributed in three frequency classes: strains at low frequency (<10%), strains at frequency ranging from 10 to 30% and predominant strains at frequency>30% (Table 3). Although according to Shannon's index “H,” estimating the richness of S. cerevisiae strains found in the six wineries, different diversity level was observed, only one S. cerevisiae strain emerged as clearly predominant in each winery except for the cellar B. Indeed, the evenness index “e,” ranging between 0 and 1 and that increases with the decreasing of the number of isolates showing the same mt-DNA, assumed the highest value in the winery B in which the predominant strain occurred at the lowest frequency value found. All the mt-DNA profiles corresponding to the different S. cerevisiae strains were also analyzed using UPGMA clustering analysis and the resulting dendrogram is reported in Figure 1. In this elaboration were also included the mt-DNA profiles of six commercial starter strains most commonly used in Tuscany. The S. cerevisiae strains, at 60% of similarity, grouped into 13 clusters mainly based on the winery where they come from, independently on the grape variety used. In particular, the S. cerevisiae strains isolated from the winery B were included in the clusters 6-7-8 and 9, while the commercial starter strains grouped in the same cluster.

Table 2.

Distribution of different mt-DNA profiles of S. cerevisiae in the six wineries (A, B, C, D, E, and F) in the same vintage.

| Winery code | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | ||||||

| mt-DNA profiles | Isolation frequency (%) | mt-DNA profiles | Isolation frequency (%) | mt-DNA profiles | Isolation frequency (%) | mt-DNA profiles | Isolation frequency (%) | mt-DNA profiles | Isolation frequency (%) | mt-DNA profiles | Isolation frequency (%) |

| AI | 1 | BI | 4.3 | CI | 9.5 | DI | 14.5 | EIV | 1.0 | FI | 25 |

| AIV | 18 | BII | 26 | CII | 2.0 | DII | 1.5 | EII | 4.0 | FII | 3 |

| AV | 7.5 | BIII | 2.2 | CIV | 5.0 | DIII | 3.0 | EIII | 5.0 | FIII | 29 |

| AVI | 8.5 | BIV | 17.4 | CIII | 74 | DIV | 52 | EI | 71 | FIV | 36 |

| AVII | 9.5 | BV | 2.2 | CV | 1.3 | DV | 0.7 | EV | 1.0 | FV | 2 |

| AX | 32 | BVI | 8.7 | CVI | 0.7 | DVI | 8.7 | EVI | 1.0 | FVII | 3 |

| AXI | 2 | BVII | 8.7 | CVII | 7.5 | DVII | 16 | EVII | 17 | FVIII | 2 |

| AXII | 14 | BVIII | 6.5 | DVIII | 0.7 | ||||||

| AXIII | 6 | BIX | 2.2 | DIX | 0.7 | ||||||

| AXIV | 1.5 | BX | 2.2 | DX | 1.5 | ||||||

| BXI | 2.2 | DXI | 0.7 | ||||||||

| BXII | 8.7 | ||||||||||

| BXIII | 2.2 | ||||||||||

| BIV | 2.2 | ||||||||||

| BXV | 2.2 | ||||||||||

| BXVI | 2.2 | ||||||||||

Predominant strains are in bold and underlined.

Table 3.

Number of mt-DNA profiles of S. cerevisiae at different isolation frequency in the six wineries and related indices Shannon and Weaver (1963).

| Winery | Frequency (%) | H | e | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10 | 10–30 | >30 | |||

| A | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1.86 | 0.81 |

| B | 14 | 2 | - | 2.35 | 0.85 |

| C | 6 | - | 1 | 1.02 | 0.49 |

| D | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1.73 | 0.61 |

| E | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1.01 | 0.46 |

| F | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1.44 | 0.74 |

H, biodiversity index; e, evenness.

Figure 1.

Dendrogram from UPGMA clustering analysis, based on Dice coefficient of mt-DNA RsaI restriction patterns of the S. cerevisiae isolates from 32 spontaneous wine fermentations carried out in six different wineries (A, B, C, D, E, and F) in Tuscany (Italy). S1-S6 indicate commercial starter cultures. Arabic numerals at 60% similarity indicate the different clusters.

In conclusion, according to these results, for each winery one predominant strain, indicated by the code HF (High Frequency), and one secondary strain, indicated by the code LF (Low Frequency), were chosen with the aim to compare their behavior in subsequent trials. The HF-S. cerevisiae strains displayed the following mt-DNA profiles: AX – BII – CIII – DIV – EI and FIV, while the LF-S. cerevisiae strains corresponded to the mt-DNA profiles AI – BI – CVI – DXI – EVI and FV.

Laboratory scale fermentation to verify the predominance behavior of HF-S. cerevisiae strains on LF-S. cerevisiae strains

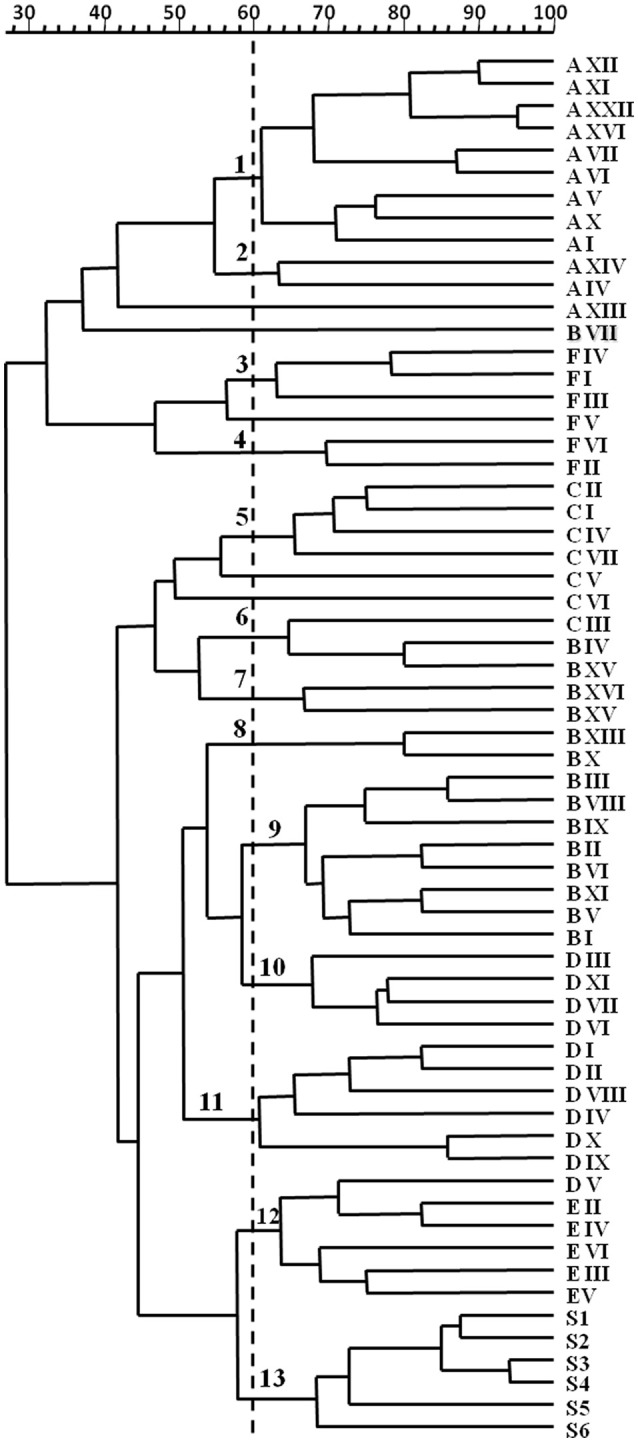

To verify whether the S. cerevisiae strains identified as HF were actually able to dominate on the strains identified as LF, laboratory-scale co-fermentations were performed. One HF and one LF strain isolated from each winery were co-inoculated in synthetic must at the same cell concentration (104 CFU/mL). This value was chosen in order to simulate the low S. cerevisiae cell densities usually found in spontaneous alcoholic fermentation. Co-fermentations carried out at 28°C by the strains from the wineries A, C, D, and F were completed in about 10 days, even if the strains from the wineries D and F showed lower fermentation rates than those from the wineries A and C (data not shown). On the contrary, the strains from winery B were unable to complete alcoholic fermentation (20% w/v of reducing sugars). During the fermentations, samples were taken at two different times (after 24 h and 10 days from the inoculation) in order to assess mt-DNA patterns of the S. cerevisiae isolates as well as their isolation frequencies. Figure 2 shows the isolation frequencies of HF and LF strains assayed for each fermentation after 24 h and 10 days from the inoculation. Although the starting inoculum of HF and LF strains was at the same cell concentration, after 24 h the isolation frequencies of the LF strains were lower than 35% in all the fermentations. After 10 days the HF strains isolated from A, B, D, and F winery showed isolation percentages of 100%, while HF strains from C and E of 96%. Therefore, the results demonstrated that during the fermentative process all the HF-S. cerevisiae strains occurred progressively at higher percentages demonstrating to retain in laboratory the “predominance behavior” displayed in industrial fermentations.

Figure 2.

Isolation frequencies of one “high frequency”(HF)-S. cerevisiae strain and one “low frequency ” (LF) S. cerevisiae strain, representative of each winery (A, B, C, D, E and F) after 24 h and 10 days in co-fermentations in synthetic must at 28°C. The “HF” and “LF” strains were inoculated at the same cell concentration (104 cell/mL).

Effect of ethanol on the growth performance and the fitness advantage of HF and LF-S. cerevisiae strains

The HF and LF-S. cerevisiae strains of the experiment previously described were also used to perform axenic fermentations in synthetic media containing various concentrations of ethanol (0-3-5 and 7% v/v). The aim of these trials was to investigate on the growth performance and on the fitness of HF and LF-strains, in order to detect any behavior justifying the different isolation frequencies observed during the spontaneous fermentations. Baranyi and Roberts-model was used to estimate the fermentative performance of the strains in terms of lag phase (λ), maximum specific growth rate (μmax) and maximum cell densities at the end of fermentations (Table 4). The goodness of fit of this model was appropriate for all the strains assayed, R2 values being, higher than 0.90 (data not shown). The findings pointed out that the μmax values of HF- strains from each winery were significantly higher than the μmax values of the LF-strains, at least in the presence of one of the ethanol concentrations considered. In particular, the HF-strains coming from A, B, E, and F wineries showed higher values in the presence of 5% ethanol, while HF-strains from wineries C and D, in the presence of 7 and 3% ethanol, respectively. Moreover, HF-strains from five wineries (A, C, D, E, and F) showed a higher growth yield than the respective LF-strains in synthetic medium containing 3 or 5% ethanol, indicating a higher alcohol tolerance of the HF-strains than LF-S. cerevisiae strains. On the contrary, only the HF-strains from the winery C and F showed a lag phase shorter than that of the respective LF-strains, when ethanol concentration was 3 or 5% (Table 4). To assess the overall effect of ethanol on the HF and LF-strains from each winery, the inhibition percentages of the growth due to ethanol was estimated comparing the area under the growth curve of the positive control (absence of ethanol) with the areas of the other conditions (presence of ethanol at different concentrations: 3, 5, and 7%). Therefore, for each strain, the percentage of inhibition determined by the different ethanol concentrations was calculated using the following formula: = [1 – (Area under the growth curve in presence of ethanol/Area under the curve without ethanol)]*100 (Table 4). This parameter is shown to be inversely related to the lag phase and linearly related to both the maximum exponential growth rate and maximum cell densities reached and thus is appropriate to assess the overall yeast growth (Arroyo-López et al., 2010). HF-S. cerevisiae strains isolated from four winery (A, C, E, and F) showed an inhibition percentages significantly lower than the LF-strains coming from the same wineries at all the concentrations of ethanol tested, while in the case of remaining two wineries, B and D, this difference was observed only at 5 and 3% of ethanol, respectively.

Table 4.

Growth parameters and inhibition percentages to ethanol of the HF and LF-S. cerevisiae strains in synthetic media at different ethanol concentrations.

| Ethanol (% v/v) | Lag phase (h) | μ (h−1) | (cell/mL)*106 | Inhibition percentages to ethanol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | LF | HF | LF | HF | LF | HF | LF | |

| Winery A | ||||||||

| 0 | 2.858 ± 0.442 | 2.705 ± 0.389 | 0.179 ± 0.003 | 0.164 ± 0.005 | 12.00 ± 0.25 | 11.75 ± 0.15 | – | – |

| 3 | 3.288 ± 0.237 | 4.349 ± 0.593 | 0.162 ± 0.011 | 0.149 ± 0.002 | 10.19 ± 0.06S | 8.69 ± 0.06 | 16.99 ± 1.72S | 36.00 ± 0.63 |

| 5 | 4.796 ± 0.274 | 4.187 ± 0.555 | 0.158 ± 0.008S | 0.058 ± 0.013 | 7.93 ± 0.18S | 3.37 ± 0.12 | 47.66 ± 1.68S | 76.93 ± 2.13 |

| 7 | 4.989 ± 0.076 | n.f.* | 0.044 ± 0.035 | n.f.* | 2.68 ± 0.06 | 2.12 ± 0.12 | 66.23 ± 4.56S | 96.42 ± 2.07 |

| Winery B | ||||||||

| 0 | 2.763 ± 0.309 | 2.523 ± 0.523 | 0.173 ± 0.007 | 0.176 ± 0.001 | 15.70 ± 0.50 | 15.10 ± 0.10 | – | – |

| 3 | 3.763 ± 0.498 | 3.782 ± 0.727 | 0.179 ± 0.020 | 0.155 ± 0.029 | 11.70 ± 0.50 | 9.10 ± 0.50 | 32.69 ± 9.61 | 32.24 ± 5.70 |

| 5 | 4.086 ± 0.287 | 3.765 ± 0.230 | 0.114 ± 0.002S | 0.097 ± 0.003 | 5.60 ± 0.01S | 4.80 ± 0.01 | 54.12 ± 0.48S | 58.04 ± 0.42 |

| 7 | 4.665 ± 2.423 | 5.451 ± 0.390 | 0.073 ± 0.049 | 0.045 ± 0.019 | 3.00 ± 0.10 | 2.60 ± 0.10 | 83.54 ± 3.50 | 89.63 ± 0.22 |

| Winery C | ||||||||

| 0 | 2.317 ± 0.185 | 1.751 ± 0.071 | 0.181 ± 0.010 | 0.159 ± 0.005 | 19.90 ± 0.70 | 17.25 ± 0.75 | – | – |

| 3 | 2.142 ± 0.059S | 3.249 ± 0.063 | 0.137 ± 0.001 | 0.135 ± 0.005 | 11.35 ± 0.15S | 9.32 ± 0.42 | 23.43 ± 1.02S | 46.83 ± 3.85 |

| 5 | 3.243 ± 0.254 | 3.130 ± 0.202 | 0.122 ± 0.011 | 0.090 ± 0.012 | 7.45 ± 0.05S | 5.30 ± 0.20 | 47.98 ± 4.79S | 61.13 ± 2.10 |

| 7 | 4.176 ± 0.774 | 4.236 ± 0.822 | 0.044 ± 0.006S | 0.025 ± 0.001 | 3.50 ± 0.25 | 2.50 ± 0.10 | 66.64 ± 0.96S | 88.61 ± 4.52 |

| Winery D | ||||||||

| 0 | 1.659 ± 0.036 | 1.501 ± 0.189 | 0.156 ± 0.005 | 0.143 ± 0.001 | 17.75 ± 0.35S | 15.63 ± 0.12 | – | – |

| 3 | 1.920 ± 0.211 | 1.479 ± 0.074 | 0.142 ± 0.001S | 0.112 ± 0.003 | 14.55 ± 0.45S | 11.50 ± 0.10 | 14.80 ± 0.46S | 19.00 ± 0.78 |

| 5 | 1.936 ± 0.001 | 1.921 ± 0.352 | 0.077 ± 0.004 | 0.068 ± 0.005 | 6.93 ± 0.31 | 6.15 ± 0.25 | 40.47 ± 0.42 | 43.39 ± 2.08 |

| 7 | 1.982 ± 0.031 | 1.995 ± 0.144 | 0.049 ± 0.006 | 0.045 ± 0.005 | 4.25 ± 0.25 | 3.75 ± 0.15 | 63.89 ± 3.46 | 73.62 ± 1.26 |

| Winery E | ||||||||

| 0 | 2.568 ± 0.008 | 2.341 ± 0.201 | 0.169 ± 0.001 | 0.169 ± 0.006 | 17.90 ± 0.30 | 18.55 ± 0.25 | – | – |

| 3 | 3.677 ± 0.005 | 3.706 ± 0.460 | 0.153 ± 0.001S | 0.102 ± 0.002 | 9.44 ± 0.19S | 5.57 ± 0.32 | 37.06 ± 1.17S | 60.19 ± 2.06 |

| 5 | 3.346 ± 0.257 | 4.062 ± 0.717 | 0.156 ± 0.010S | 0.077 ± 0.009 | 7.15 ± 0.20S | 3.87 ± 0.12 | 59.05 ± 1.81S | 78.74 ± 4.43 |

| 7 | 4.042 ± 0.077 | 5.124 ± 1.200 | 0.038 ± 0.001S | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 2.87 ± 0.12S | 2.19 ± 0.06 | 82.39 ± 1.17S | 96.30 ± 2.34 |

| Winery F | ||||||||

| 0 | 0.340 ± 0.210S | 1.436 ± 0.223 | 0.136 ± 0.005 | 0.136 ± 0.004 | 18.00 ± 0.10 | 17.40 ± 0.40 | – | – |

| 3 | 0.790 ± 0.236S | 1.878 ± 0.023 | 0.123 ± 0.006 | 0.117 ± 0.001 | 13.00 ± 0.40S | 9.37 ± 0.37 | 19.17 ± 3.22S | 35.52 ± 3.20 |

| 5 | 1.342 ± 0.144S | 2.464 ± 0.090 | 0.097 ± 0.004S | 0.075 ± 0.007 | 7.81 ± 0.18S | 5.14 ± 0.24 | 45.80 ± 1.50S | 63.86 ± 0.10 |

| 7 | 4.175 ± 0.306 | 4.670 ± 0.744 | 0.105 ± 0.004S | 0.055 ± 0.007 | 5.14 ± 0.24S | 2.96 ± 0.16 | 77.30 ± 0.38S | 88.77 ± 3.48 |

The growth parameters were calculated using Baranyi and Roberts-model (Combase DMfit software), the inhibition percentages to ethanol were calculated using the following formula: = [1- (Area under the growth curve in presence of ethanol/Area under the curve without ethanol)]* 100. All the results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; S, significant different (t-Test; p < 0.05); n.f., no significant fit.

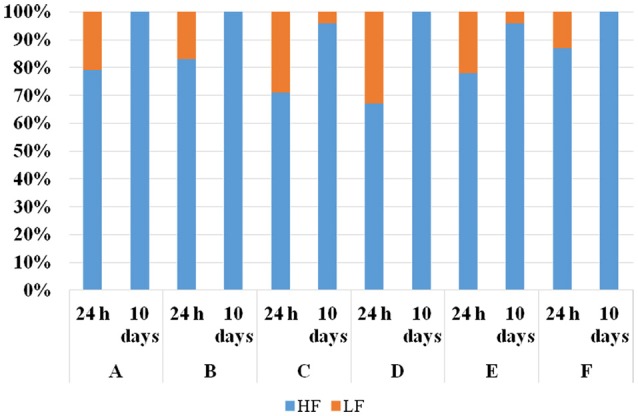

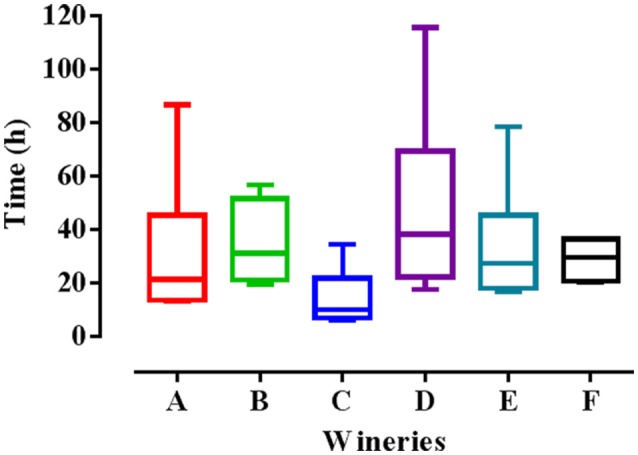

Finally, to quantify how increasing ethanol concentrations affects competition between HF- and LF-strains isolated from each winery, the concept of fitness advantage (Goddard, 2008; Salvadó et al., 2011) was used. Two main factors affect the yeast fitness: the maximum specific growth rate (μmax) and the duration of the lag phase (Buchanan and Solberg, 1972; Swinnen et al., 2004; Oxman et al., 2008). Therefore, in order to consider both factors, the fitness advantage was calculated taking into account the average growth rate (v) between 0 and 8 h using the following mathematical formula: fitness advantage (m) = v HF – v LF. In Figure 3, the data obtained at different ethanol concentrations, ranging from 0.01 to 0.11 (h−1), are shown. Independently on ethanol concentration, values resulted positive, demonstrating the fitness advantage of HF-S. cerevisiae—strains.

Figure 3.

Fitness advantage at different ethanol concentrations calculated for each pair of HF/LF-S. cerevisiae strains from the six different wineries (A, B, C, D, E, and F) considering the average growth rate calculated between 0 and 8 h in synthetic medium at 28°C.

Combined effect of temperature and ethanol on the growth performance and the fitness advantage of HF and LF-S. cerevisiae strains

Temperature and ethanol can considerably affect yeast growth and thus the wine fermentation kinetics. The contemporary presence of these two factors could play an important role in niche construction favoring some strains of S. cerevisiae compared to others in wine fermentation. To prove this selective effect, the combined effect of these two parameters on HF and LF-strains was studied in laboratory scale fermentation planning the experiment according to a central composite design with two variable (ethanol and temperature) and three-level. In particular, the three conditions of temperatures were 25, 30, and 35°C, while the three concentrations of ethanol were 0, 3.5, and 7%, obtaining nine combinations in total. Gompertz model was used to estimate the performances of the strains in terms of lag phase period, maximum specific growth rate (μmax) and maximum cell densities of the various fermentation kinetics (Table 5). The goodness of fit of this model was appropriate for all the strains assayed, R2 values being, higher than 0.95 (data not shown). The comparison between the growth performances of each pair of strains representative of the six wineries showed that, when significant differences occurred they were always in favor of HF instead of LF strains (shorter lag phase, higher maximum specific growth rate, higher maximum cell densities). Similarly, the inhibition percentages due to the combined effect of ethanol and temperature, when differences were statistically significant, were always higher for the LF strains compared to the HF-strains.

Table 5.

Growth parameters and inhibition percentages to ethanol of the HF and LF-S. cerevisiae strains in synthetic media at different ethanol concentrations.

| Ethanol (% v/v) | Temperature (°C) | Lag phase (h) | μ (h−1) | C (Log cell/mL) | Inhibition percentages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | LF | HF | LF | HF | LF | HF | LF | ||

| Winery A | |||||||||

| 0 | 25 | 1.173 ± 0.004S | 1.478 ± 0.058 | 0.1478 ± 0.0001 | 0.1493 ± 0.0027 | 1.429 ± 0.001 | 1.444 ± 0.002 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 25 | 1.094 ± 0.014S | 2.060 ± 0.056 | 0.1028 ± 0.0001S | 0.0810 ± 0.0001 | 1.240 ± 0.001 | 1.245 ± 0.014 | 26.14 ± 0.24S | 49.12 ± 1.08 |

| 7 | 25 | 2.468 ± 0.044S | 5.100 ± 0.356 | 0.0646 ± 0.0009 | 0.0643 ± 0.0015 | 1.183 ± 0.011 | 1.165 ± 0.0034 | 64.98 ± 0.14S | 83.37 ± 1.82 |

| 0 | 30 | 1.004 ± 0.071S | 1.841 ± 0.040 | 0.1861 ± 0.0027 | 0.2081 ± 0.0075 | 1.331 ± 0.006S | 1.280 ± 0.002 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 30 | 1.040 ± 0.052S | 1.886 ± 0.116 | 0.1028 ± 0.0007S | 0.08164 ± 0.0019 | 1.236 ± 0.005S | 1.132 ± 0.006 | 34.13 ± 0.54S | 56.22 ± 0.05 |

| 7 | 30 | 1.705 ± 0.062S | 3.576 ± 0.007 | 0.0656 ± 0.0002S | 0.04307 ± 0.0007 | 0.677 ± 0.001S | 0.498 ± 0.004 | 66.33 ± 1.04S | 87.11 ± 2.57 |

| 0 | 35 | 0.248 ± 0.041S | 1.732 ± 0.136 | 0.1245 ± 0.0015S | 0.1650 ± 0.0075 | 1.295 ± 0.004S | 1.137 ± 0.002 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 35 | 1.040 ± 0.053S | 1.886 ± 0.016 | 0.06763 ± 0.0005S | 0.0607 ± 0.0009 | 0.813 ± 0.012S | 0.734 ± 0.002 | 48.38 ± 0.55 | 48.98 ± 0.07 |

| 7 | 35 | 1.463 ± 0.302 | 2.798 ± 0.456 | 0.03562 ± 0.0019 | 0.0300 ± 0.0026 | 0.321 ± 0.021 | 0.184 ± 0.006 | 79.96 ± 0.57S | 87.55 ± 1.11 |

| Winery B | |||||||||

| 0 | 25 | 1.685 ± 0.010 | 1.643 ± 0.086 | 0.1862 ± 0.0045 | 0.2073 ± 0.0055 | 1.264 ± 0.002S | 1.232 ± 0.004 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 25 | 1.642 ± 0.224 | 1.522 ± 0.319 | 0.0920 ± 0.0002S | 0.0797 ± 0.0006 | 1.135 ± 0.012S | 1.030 ± 0.0082 | 45.06 ± 0.20S | 54.63 ± 0.88 |

| 7 | 25 | 2.698 ± 0.115S | 4.654 ± 0.044 | 0.0515 ± 0.0002 | 0.0574 ± 0.0018 | 1.065 ± 0.058 | 1.077 ± 0.209 | 68.60 ± 0.76 | 78.37 ± 2.96 |

| 0 | 30 | 1.324 ± 0.090 | 1.775 ± 0.050 | 0.2394 ± 0.0022 | 0.2296 ± 0.0041 | 1.240 ± 0.006 | 1.246 ± 0.002 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 30 | 1.899 ± 0.068 | 2.172 ± 0.075 | 0.1552 ± 0.0030S | 0.1419 ± 0.0023 | 1.116 ± 0.008S | 0.982 ± 0.005 | 31.29 ± 0.76S | 42.59 ± 0.46 |

| 7 | 30 | 1.960 ± 0.046S | 2.760 ± 0.043 | 0.0459 ± 0.0050 | 0.0398 ± 0.0017 | 0.675 ± 0.012 | 0.609 ± 0.013 | 72.34 ± 1.73 | 72.45 ± 0.99 |

| 0 | 35 | 1.789 ± 0.066 | 1.635 ± 0.018 | 0.2360 ± 0.0145 | 0.2343 ± 0.0009 | 1.220 ± 0.018 | 1.238 ± 0.001 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 35 | 1.900 ± 0.378 | 3.065 ± 0.002 | 0.1336 ± 0.0087 | 0.1523 ± 0.0031 | 1.045 ± 0.020S | 0.705 ± 0.011 | 39.00 ± 2.13S | 58.31 ± 0.65 |

| 7 | 35 | 2.336 ± 0.075 | 3.140 ± 0.218 | 0.0223 ± 0.0010 | 0.0243 ± 0.0005 | 0.636 ± 0.119 | 0.451 ± 0.036 | 82.78 ± 0.66 | 84.66 ± 0.96 |

| Winery C | |||||||||

| 0 | 25 | 0.755 ± 0.039S | 1.132 ± 0.072 | 0.1418 ± 0.0006 | 0.1464 ± 0.0032 | 1.453 ± 0.002S | 1.321 ± 0.007 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 25 | 0.719 ± 0.067S | 2.351 ± 0.214 | 0.1197 ± 0.0011 | 0.1306 ± 0.0066 | 1.345 ± 0.001S | 1.147 ± 0.003 | 59.12 ± 1.09S | 69.31 ± 0.52 |

| 7 | 25 | 1.129 ± 0.152S | 15.140 ± 0.262 | 0.0880 ± 0.0030 | 0.0999 ± 0.0017 | 1.151 ± 0.001S | 0.868 ± 0.067 | 84.79 ± 1.03S | 92.52 ± 0.38 |

| 0 | 30 | 1.044 ± 0.143 | 1.023 ± 0.082 | 0.1571 ± 0.0042 | 0.1647 ± 0.0024 | 1.277 ± 0.001 | 1.267 ± 0.002 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 30 | 1.102 ± 0.027S | 1.023 ± 0.002 | 0.1438 ± 0.0002S | 0.1295 ± 0.0019 | 1.062 ± 0.009S | 0.993 ± 0.004 | 47.88 ± 0.18S | 55.32 ± 1.21 |

| 7 | 30 | 1.474 ± 0.090S | 8.693 ± 1.092 | 0.0815 ± 0.0011S | 0.0553 ± 0.0038 | 0.9602 ± 0.005 | 0.801 ± 0.269 | 82.25 ± 0.21S | 93.73 ± 0.94 |

| 0 | 35 | 0.734 ± 0.101 | 0.830 ± 0.067 | 0.1616 ± 0.0042 | 0.1580 ± 0.0019 | 1.107 ± 0.009 | 1.128 ± 0.002 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 35 | 0.734 ± 0.174S | 3.464 ± 0.237 | 0.1352 ± 0.0006 | 0.1382 ± 0.0083 | 1.041 ± 0.040 | 0.941 ± 0.001 | 85.97 ± 2.86 | 82.73 ± 2.01 |

| 7 | 35 | 0.818 ± 0.055S | 7.352 ± 0.247 | 0.05821 ± 0.0003 | 0.0511 ± 0.0057 | 0.755 ± 0.001S | 0.259 ± 0.015 | 94.72 ± 0.21 | 97.68 ± 0.02 |

| Winery D | |||||||||

| 0 | 25 | 2.983 ± 0.073S | 2.436 ± 0.019 | 0.2043 ± 0.0027S | 0.1592 ± 0.0020 | 1.254 ± 0.007 | 1.234 ± 0.016 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 25 | 4.631 ± 0.061 | 5.138 ± 0.207 | 0.1638 ± 0.0016 | 0.1349 ± 0.0111 | 0.992 ± 0.009 | 1.158 ± 0.045 | 33.92 ± 0.15S | 51.12 ± 0.67 |

| 7 | 25 | 5.654 ± 0.129S | 6.979 ± 0.029 | 0.0872 ± 0.0056 | 0.0867 ± 0.0078 | 0.990 ± 0.018 | 1.001 ± 0.030 | 74.40 ± 0.01 | 90.49 ± 4.57 |

| 0 | 30 | 2.108 ± 0.017S | 2.225 ± 0.001 | 0.1905 ± 0.0020 | 0.1903 ± 0.0010 | 1.253 ± 0.001S | 1.264 ± 0.002 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 30 | 3.156 ± 0.071 | 3.193 ± 0.027 | 0.1403 ± 0.0019S | 0.1126 ± 0.0014 | 1.187 ± 0.011S | 1.092 ± 0.011 | 43.33 ± 0.52S | 55.47 ± 0.03 |

| 7 | 30 | 4.811 ± 0.049S | 6.947 ± 0.193 | 0.0924 ± 0.0022 | 0.0801 ± 0.0073 | 0.927 ± 0.010 | 1.022 ± 0.034 | 84.52 ± 1.11 | 89.77 ± 1.63 |

| 0 | 35 | 2.692 ± 0.026S | 2.467 ± 0.025 | 0.1849 ± 0.0011S | 0.1639 ± 0.0015 | 1.229 ± 0.011S | 1.090 ± 0.004 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 35 | 6.020 ± 0.036S | 5.696 ± 0.016 | 0.0717 ± 0.0003S | 0.0601 ± 0.0001 | 1.013 ± 0.046 | 1.449 ± 0.279 | 44.05 ± 0.23S | 58.44 ± 0.98 |

| 7 | 35 | 7.212 ± 0.013S | 8.311 ± 0.015 | 0.0661 ± 0.0037 | 0.0473 ± 0.0031 | 1.039 ± 0.006S | 0.635 ± 0.019 | 78.88 ± 1.44S | 95.49 ± 1.40 |

| Winery E | |||||||||

| 0 | 25 | 2.148 ± 0.003 | 2.318 ± 0.161 | 0.1603 ± 0.0021 | 0.1713 ± 0.0099 | 1.252 ± 0.0035 | 1.231 ± 0.0095 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 25 | 2.597 ± 0.016S | 3.695 ± 0.109 | 0.1180 ± 0.0016 | 0.1343 ± 0.0053 | 1.186 ± 0.005 | 1.125 ± 0.035 | 41.47 ± 0.10S | 57.86 ± 0.21 |

| 7 | 25 | 4.051 ± 0.003S | 6.372 ± 0.063 | 0.06499 ± 0.0018 | 0.08217 ± 0.0302 | 1.043 ± 0.008 | 1.018 ± 0.142 | 75.15 ± 0.12S | 87.19 ± 1.46 |

| 0 | 30 | 1.456 ± 0.156 | 1.958 ± 0.065 | 0.1924 ± 0.0055S | 0.1584 ± 0.0042 | 1.254 ± 0.013 | 1.139 ± 0.001 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 30 | 2.008 ± 0.075S | 3.069 ± 0.067 | 0.1161 ± 0.0003S | 0.0998 ± 0.0030 | 1.109 ± 0.008S | 0.947 ± 0.008 | 34.07 ± 0.58S | 51.87 ± 0.49 |

| 7 | 30 | 4.715 ± 0.072 | 5.407 ± 0.586 | 0.0392 ± 0.0015 | 0.03448 ± 0.0005 | 2.233 ± 0.033S | 1.295 ± 0.177 | 79.29 ± 0.43 | 87.89 ± 2.05 |

| 0 | 35 | 0.7815 ± 0.020S | 1.686 ± 0.116 | 0.1171 ± 0.0016 | 0.1399 ± 0.0052 | 1.147 ± 0.014 | 1.107 ± 0.024 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 35 | 1.450 ± 0.061S | 3.015 ± 0.097 | 0.07534 ± 0.0051 | 0.08448 ± 0.0018 | 0.932 ± 0.051 | 0.8141 ± 0.021 | 47.08 ± 0.43S | 53.24 ± 0.19 |

| 7 | 35 | 2.177 ± 0.452 | 3.446 ± 0.814 | 0.0350 ± 0.0038S | 0.007538 ± 0.010 | 0.4133 ± 0.009S | 0.1737 ± 0.007 | 85.05 ± 1.35S | 95.11 ± 1.28 |

| Winery F | |||||||||

| 0 | 25 | 1.516 ± 0.015 | 1.582 ± 0.096 | 0.1610 ± 0.0009 | 0.1613 ± 0.0017 | 1.229 ± 0.002 | 1.244 ± 0.008 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 25 | 2.547 ± 0.003S | 3.450 ± 0.017 | 0.1250 ± 0.0015 | 0.1220 ± 0.0021 | 1.105 ± 0.007 | 1.020 ± 0.033 | 13.20 ± 1.08S | 36.41 ± 1.26 |

| 7 | 25 | 4.057 ± 0.043S | 5.597 ± 0.347 | 0.0925 ± 0.0029 | 0.1145 ± 0.0123 | 0.890 ± 0.003S | 0.733 ± 0.004 | 41.28 ± 0.82S | 85.72 ± 1.61 |

| 0 | 30 | 1.623 ± 0.012 | 1.712 ± 0.017 | 0.1880 ± 0.0022 | 0.1972 ± 0.0016 | 1.223 ± 0.005 | 1.175 ± 0.024 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 30 | 1.741 ± 0.132S | 2.726 ± 0.031 | 0.1226 ± 0.0051 | 0.1225 ± 0.0010 | 1.012 ± 0.017S | 0.8961 ± 0.007 | 11.48 ± 0.08S | 48.16 ± 1.66 |

| 7 | 30 | 3.273 ± 0.043 | 4.957 ± 0.755 | 0.08269 ± 0.0222 | 0.0808 ± 0.0235 | 0.987 ± 0.058 | 0.948 ± 0.348 | 50.83 ± 0.19S | 91.62 ± 1.24 |

| 0 | 35 | 0.939 ± 0.001 | 1.424 ± 0.042 | 0.1686 ± 0.0003 | 0.1717 ± 0.0010 | 1.187 ± 0.007S | 0.9929 ± 0.002 | – | – |

| 3.5 | 35 | 1.905 ± 0.035S | 2.570 ± 0.084 | 0.1206 ± 0.0070 | 0.1185 ± 0.0079 | 0.7066 ± 0.016S | 0.5607 ± 0.027 | 13.21 ± 2.20S | 59.33 ± 0.38 |

| 7 | 35 | 3.306 ± 0.466 | 4.879 ± 0.548 | 0.0430 ± 0.0061 | 0.0227 ± 0.0020 | 0.6424 ± 0.033S | 0.3017 ± 0.035 | 47.02 ± 0.86S | 98.09 ± 0.99 |

The growth parameters were calculated using Gompertz function (GraphPadPrism software), the inhibition percentages to ethanol at different temperatures were calculated using the following formula: = [1 – (Area under the growth curve in presence of ethanol at a 25, 30 or 35°C/Area under the curve without ethanol at a 25, 30, or 35°C)]*100. All the results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; S, significant different (t-Test; p < 0.05); n.f., no significant fit.

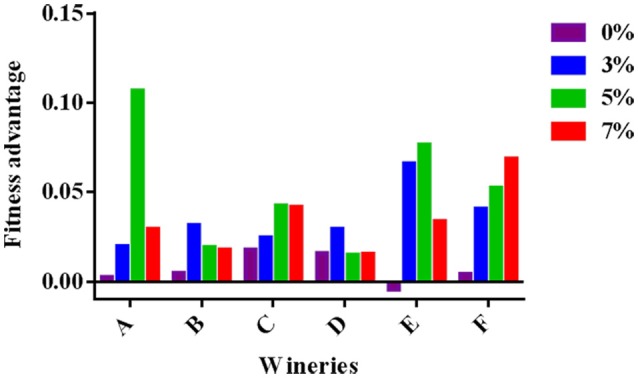

Finally, the fitness advantage between the HF and LF strains was calculated for each winery taking into account the average growth rate between 0 and 8 h (v) using the mathematical formula reported above. As shown in Figure 4, the advantage of HF-S. cerevisiae strains was pointed out in most cases, with few exceptions (5 in total).

Figure 4.

Fitness advantage at different concentrations of ethanol and temperatures calculated for each pair of HF/LF-S. cerevisiae strains from the six different wineries (A, B, C, D, E, and F), considering the average growth rate calculated between 0 and 8 h in synthetic medium.

Theoretical time required to achieve dominance of HF on LF-S. cerevisiae strains

Fitness advantage in a specific competitive environment can explain why a given strain outcompetes another. Therefore, the values of fitness advantage reported in Figure 4 can be used to calculate the theoretical time (t) needed for HF-strains to dominate on LF-strains. The equation to calculate “t” was developed by Hartl and Clark (1997) and recently were used by Goddard (2008) and García-Ríos et al. (2014):

where “m” was the fitness advantage, “p” the frequency of HF-S. cerevisiae strains, “q” the frequency of LF-S. cerevisiae strains. In particular, p0 and q0 were the initial frequencies, while pt and qt were the final frequencies. The initial frequencies of both HF and LF-strains were imposed at 0.50, while the final frequencies were 0.90 and 0.10 for HF and LF-strains, respectively. In Figure 5 are reported the theoretical times required in each winery to achieve dominance of HF-S. cerevisiae on LF-strains. Theoretically, the assayed HF-S. cerevisiae strains takes an average of 14 to almost 50 h to dominate on LF-S. cerevisiae strains according to the winery considered. These theoretical values were in agreement with the experimental data obtained from laboratory-scale co-fermentations carried out by one HF and one LF strain that were inoculated in synthetic must at the same initial concentrations corresponding to frequencies at 0.50. Indeed, in each of six co-fermentations the HF-S. cerevisiae strain dominated on LF-strain within the first 24 h.

Figure 5.

Theoretical time required by HF-S. cerevisiae strains to dominate on LF-S. cerevisiae strains in the six wineries studied (A, B, C, D, E, and F).

Discussion

In spontaneous wine fermentation, different yeast species as well as various strains of the same species, usually coexist interacting with each other and the environmental conditions (Albergaria and Arneborg, 2016; Ciani et al., 2016; Morrison-Whittle and Goddard, 2018). Since during the alcoholic fermentation progress many changes occur in grape must becoming wine, the environmental conditions turn out to be more selective, and different yeast species and strains undergo sequential substitution in relation to their fitness for such harsh conditions (Bisson, 2012; Perrone et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2015; Ciani et al., 2016; Brice et al., 2018; Henriques et al., 2018). Different studies have raised evidence that the dominance of S. cerevisiae on non-Saccharomyces yeast species, that usually takes place in the first stages of spontaneous wine fermentation, is dependent on, not only higher tolerance to ethanol, but also on temperature (Goddard, 2008; Salvadó et al., 2011; Alonso del-Real et al., 2017), and other factors such as cell-to-cell contact mechanism (Nissen and Arnebor, 2003). On the other hand, few studies have investigated the dominance of S. cerevisiae strains during spontaneous or induced wine fermentation (Perrone et al., 2013; García-Ríos et al., 2014; Pérez-Torrado et al., 2017).

In this work, the influence of ethanol and temperature on the dominance of different S. cerevisiae strains, occurring in several spontaneous alcoholic fermentations carried out at industrial level in six wineries in Tuscany (Italy), was assayed by using the concept of fitness advantage (García-Ríos et al., 2014). The predominant S. cerevisiae strains were differentiated by RFLP-mtDNA method and according to their isolation frequency. The results obtained, by analyzing 637 isolates, confirmed the genetic polymorphism expected for S. cerevisiae population in spontaneous wine fermentations and the high variability between the isolation frequencies of different strains (Bisson, 2012; Schuller et al., 2012; Tofalo et al., 2013). In particular, independently of the grape variety, five out six wineries considered, showed only one predominant S. cerevisiae strain, with an isolation frequency ranging from 32 to 74%, while a variable number of strains (from 4 to 14) was characterized by an isolation frequency lower than 10%. These finding were consistent with those reported by other Authors (Versavaud et al., 1995; Gutiérrez et al., 1997; Egli et al., 1998; Sabate et al., 1998) although in some cases S. cerevisiae strains predominating the fermentative process, were not found (Vezinhet et al., 1992; Torija et al., 2001). In agreement with other studies (Versavaud et al., 1995; Barrajón et al., 2010), the indigenous S. cerevisiae strains were differentiated in two groups: strains at high frequency (HF) or “predominant” and strains at low frequency (LF) or “secondary” strains. Moreover, our results demonstrated that the S. cerevisiae strains dominating spontaneous wine fermentations were not related to the grape variety used to perform alcoholic fermentations; instead, they were representative of different wineries, strengthening the idea of the occurrence of yeast strains possessing better fitness to the specific winemaking conditions used in each winery (Cocolin et al., 2004). Probably, during the usual cellar operations, yeast strains spread throughout the environment and those that were better adapted to certain conditions occurred at higher frequencies, becoming the dominant yeast strains in the winery. In the literature, in some cases S. cerevisiae strains were found to be capable of dominating the alcoholic fermentation in all vats of the same winery, independently of the grapevine cultivar (Frezier and Dubourdieu, 1992; Guillamón et al., 1996), whereas other times the yeast strains were found to be specific for each grape variety (Blanco et al., 2006; Schuller et al., 2012).

In any case, cluster analysis with the Dice coefficient and the UPGMA method grouped the profiles of predominant (HF) and secondary (LF) S. cerevisiae strains in clusters according to the winery where they came from. Furthermore, the yeast commercial strains assayed in this study, chosen because they are the most frequently used in Tuscany as starter cultures, grouped into a distinct cluster indicating that they were significantly different from the indigenous strains, probably because of they were isolated from French oenological areas. Mercado et al. (2011), by using two molecular methods (RFL-mtDNA and interdelta PCR) observed a clear separation between S. cerevisiae strains isolated from vineyard and commercial strains, while in other study on cellar-associated S. cerevisiae population structure “only 7% of cellar strains were found to be related to commercial strains usually used” as starter cultures (Börlin et al., 2016). On the contrary, Martiniuk et al. (2016) found that commercial and commercial-related yeasts occurred in spontaneous fermentations of a Canadian winery, although they did not dominate the S. cerevisiae populations that were unrelated to commercial strains present in the same fermentations. Concerning this work, it should be emphasized that five out of six wineries here taken into account never used commercial yeast strains and only the winery E used the S1 strain as starter some years before the survey.

The occurrence of specific S. cerevisiae strains in each winery supports the potential role of these microorganisms in determining distinctive wine characteristics and their selection could represent a resource to contribute in preserving the typicality of wines (Vezinhet et al., 1992; Augruso et al., 2008; Aponte and Blaiotta, 2016; Bokulich et al., 2016). Recent studies suggested the concept of “the so-called microbial terroir” demonstrating that indigenous yeast strains can be associated to a given viticultural region (Bokulich et al., 2016; Morrison-Whittle and Goddard, 2018). However, according to our results, specific S. cerevisiae strains seem to be representative of single winery rather than of an oenological area: three out six wineries (A, B, and C) were situated within 10 km radius, and showed S. cerevisiae grouped in three different clusters. Therefore, data suggested the idea of the “winery effect” or a microbial terroir at a smaller scale. Nevertheless, in order to assess the existence of certain relationship between indigenous S. cerevisiae strains and single winery, further surveys in consecutive years in the same wineries located in different oenological areas should be carried out.

The further step was addressed to confirm, in laboratory-scale fermentations, the dominant behavior, exhibited by S. cerevisiae strains at high frequency (HF) in the spontaneous alcoholic fermentations in each winery. Co-fermentations were carried out by inoculating at the same cell densities (104 cell/mL) one HF-strain and one LF-strain coming from the six wineries, and the ability of one strain to dominate over another was assayed by using the RFLP-mtDNA method. The data obtained raised evidence that after 24 h in co-fermentations total yeast population reached values of 107 CFU/mL and that in all our trials the “HF” S. cerevisiae strain occurred at frequency ranging from 70 to 87%, confirming the dominance behavior observed in industrial spontaneous fermentations in the six wineries. Other Authors (Barrajón et al., 2010; Perrone et al., 2013; Pérez-Torrado et al., 2017) that assayed the competition between indigenous “dominant” S. cerevisiae strains and commercial yeasts or between one “dominant” and one “non-dominant” strain by using co-fermentations, reported similar results. This dominance phenomenon has been mainly attributed to a cell-to-cell contact mechanism or microenvironment contact, conditions in which cells compete for space when are in high densities and in cell-to-cell contact, so that the non-dominant yeast strain arrests its growth (Ciani et al., 2016). Moreover, a differential sulphite production and resistance and the killer activity seemed to be involved in dominant behavior of the yeast strains (Perrone et al., 2013; Pérez-Torrado et al., 2017). It is noteworthy that no killer activity was detected in HF-strains assayed in this study and no significant differences in sulphite production were found (data not shown).

Nevertheless, the competition degree of each strain, which determine the capacity of one strain to out-compete another, is influenced by other factors including pH, temperature, ethanol, osmotic pressure, nitrogen available (Ciani et al., 2016). Indeed, our findings concerning the influence of ethanol and temperature on the growth performance and the fitness advantage of High frequency (HF) S. cerevisiae strains, support the important role that these two factors may play in determining the dominance of one strain over another in wine fermentations. By considering the single effect of ethanol on growth performance, “HF” strains showed significant lower inhibition percentages than “LF” strains although in the presence of different ethanol concentrations (from 3 to 7%). The inhibition percentages, calculated as reported by Arroyo-López et al. (2009, 2010), was an appropriate indicator of the overall yeast growth as this parameter was inversely related to the lag phase, but linearly related to both the maximum specific growth rate (μmax) and the maximum cell densities at the end of growth. Consequently, the fitness advantage, which according to Salvadó et al. (2011) represents the difference in μmax between competitors for a specific environmental condition, resulted higher for “HF” strains, suggesting their better adaptability to increasing ethanol concentrations in comparison with “LF” strains. However, this capability resulted to be a strain-dependent characteristic as the fitness advantage showed values ranging from 1 to 6% per hour and from 1 to 10% per hour in the presence of 3 and 5% ethanol, respectively. Indeed, each S. cerevisiae strains may display different stress responses to ethanol as the effects of increasing ethanol concentrations on the yeast cell include different changes such as in membrane composition and in gene expression, synthesis of heat shock proteins, increases in chaperons proteins etc. (Ding et al., 2009). Recently, a study aimed to assess fitness advantages of four commercial wine yeast strains has stressed that fermentation temperature might be an important factor in determining the dynamics of the S. cerevisiae strain population (García-Ríos et al., 2014). In fact, ethanol and high temperature affect synergistically the membrane integrity and permeability causing a decrease in the growth of yeast populations (Alexandre et al., 1994; Albergaria and Arneborg, 2016). The data related to the combined effect of increasing ethanol concentrations and different temperatures on the growth performance and the fitness advantages of six couple of HF and LF-S. cerevisiae here considered, confirmed that these two factors could play an important role in niche construction favoring some strains of S. cerevisiae compared to others in wine fermentation. According to some studies, the competitive advantage of S. cerevisiae on non-Saccharomyces yeasts in spontaneous alcoholic fermentations seems to be related to both ethanol and temperature adaptation (Goddard, 2008; Salvadó et al., 2011; Ciani et al., 2016; Alonso del-Real et al., 2017). Therefore, similar competition mechanisms might be responsible for interaction among indigenous S. cerevisiae strains. Our results proved that the six “HF” strains had always fitness advantage in comparison with relative LF strains when temperature was 25 or 30°C in the presence of ethanol concentrations of 3.5 and 7% v/v. These conditions typically occur in the early stages of alcoholic fermentations and suggest that they can affect the competition among different S. cerevisiae strains during the first 2 days of the fermentative process.

Taking into account values of fitness advantage obtained at different temperature and ethanol concentrations was calculated the hypothetical time needed for each “HF”-S. cerevisiae to achieve dominance on the relative “LF”-S. cerevisiae strain in a theoretical mixed population in which each strain was equally represented (50%) (García-Ríos et al., 2014). Results showed that assayed “HF”-S. cerevisiae strains took an average of 14 to almost 50 h to dominate on “LF”-S. cerevisiae strains based in relation to the winery where they originated.

In conclusions, these findings support the key role of ethanol and temperature in determining fitness advantage of some S. cerevisiae strains and contribute to the understanding of predominance of S. cerevisiae strains in spontaneous wine fermentations, even though other factor and or mechanisms can be involved. Moreover, these yeast strains could be exploited to develop new wine starters able to guarantee a high fermentative performance in grape musts even under stressful conditions and a positive metabolites production in the final wine (Bonciani et al., 2016). Recently, in order to achieve this goal, the construction of hybrid S. cerevisiae strains has been performed through selection programs based on the adaptive evolution strategy or a multi-phase approach (Bonciani et al., 2018), valuable tools to obtain improved and suitable yeast strains in the modern oenology.

Author contributions

SG, DG, SM, and LG conceived and designed the experiments. SM contributed to perform chemical analysis. DG contributed to perform microbiological analysis and genotyping characterization of S. cerevisiae isolates. SG and LG contributed to statistical analysis and interpretation of data for the work, to draft the work and revising it. MV contributed to the revision of the work.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Agnolucci M., Scarano S., Santoro S., Sassano C., Toffanin A., Nuti M. (2007). Genetic and phenotypic diversity of autochthonous Saccharomyces spp. strains associated to natural fermentation of ‘Malvasia delle Lipari’. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 45, 657–662. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02244.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albergaria H., Arneborg N. (2016). Dominance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in alcoholic fermentation processes: role of physiological fitness and microbial interactions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 2035–2046. 10.1007/s00253-015-7255-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre H., Rousseaux I., Charpentier C. (1994). Relationship between ethanol tolerance, lipid composition and plasma membrane fluidity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kloeckera apiculata. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 124,17–22. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso del-Real J., Lairón-Peris M., Barrio E., Querol A. (2017). Effect of temperature on the prevalence of Saccharomyces non - cerevisiae species against a S. cerevisiae wine strain in wine fermentation: competition, physiological fitness, and influence in final wine composition. Front. Microbiol. 8:150. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte M., Blaiotta G. (2016). Selection of an autochthonous Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain for the vinification of “Moscato di Saracena”, a southern Italy (Calabria Region) passito wine. Food Microbiol. 54, 30–39. 10.1016/j.fm.2015.10.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-López F. N., Pérez-Través L., Querol A., Barrio E. (2011). Exclusion of Saccharomyces kudriavzevii from a wine model system mediated by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 28, 423–435. 10.1002/yea.1848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-López F. N., Querol A., Barrio E. (2009). Application of a substrate inhibition model to estimate the effect of fructose concentration on the growth of diverse Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 36, 663–669. 10.1007/s10295-009-0535-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo-López F. N., Salvad,ò Z., Tronchoni J., Guillamòn J. M., Barrio E., Querol A. (2010). Susceptibility and resistance to ethanol in Saccharomyces strains isolated from wild and fermentative environments. Yeast 27, 1005–1015. 10.1002/yea.1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augruso S., Ganucci D., Buscioni G., Granchi L., Vincenzini M. (2008). A ogni cantina il suo lievito? VQ 5, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Augruso S., Granchi L., Vincenzini M. (2005). Biodiversità intraspecifica di Saccharomyces cerevisiae e ambiente vitivinicolo. VQ 7, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Baranyi J., Roberts T. A. (1994). A dynamic approach to predicting bacterial growth in food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 23, 277–294. 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90157-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrajón N., Arévalo-Villena M., ûbeda J., Briones A. (2010). “Communicating current research and education topics and trends in applied microbiology and microbiology book series,” Competition between Spontaneous and Commercial Yeasts in Winemaking: study of Possible Factors Involved, Vol. 2, eds Mendez-Vilas A. (Badajoz: Formatex Research Center; ), 1035–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Barrajón N., Capece A., Arévalo-Villena M., Briones A., Romano P. (2011). Co-inoculation of different Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains and influence on volatile composition of wines. Food Microbiol. 28, 1080–1086. 10.1016/j.fm.2011.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson L. F. (2005). The biotechnology of wine yeast. Food Biotechnol. 18, 63–96. 10.1081/FBT-120030385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson L. F. (2012). Geographic origin and diversity of wine strains of Saccharomyces. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 63, 165–175. 10.5344/ajev.2012.11083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco P., Ramilo A., Cerdeira M., Orriols I. (2006). Genetic diversity of wine Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains in an experimental winery from Galicia (NW Spain). Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 89, 351–357. 10.1007/s10482-005-9038-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich N. A., Collins T. S., Masarweh C., Allene G., Heymann H., Ebeler S. E., et al. (2016). Associations among wine grape microbiome, metabolome, and fermentation behavior suggest microbial contribution to regional wine characteristics. MBio 7:e00631-16. 10.1128/2FmBio.00631-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonciani T., De Vero L., Mezzetti F., Fay J. C., Giudici P. (2018). A multi-phase approach to select new wine yeast strains with enhanced fermentative fitness and glutathione production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 2269–2278. 10.1007/s00253-018-8773-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonciani T., Solieri L., De Vero L., Giudici P. (2016). Improved wine yeasts by direct mating and selection under stressful fermentative conditions. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 242, 899–910. 10.1007/s00217-015-2596-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Börlin M., Venet P., Claisse O., Salin F., Legras J. L., Masneuf-Pomarede I. (2016). Cellar-associated Saccharomyces cerevisiae population structure revealed high-level diversity and perennial persistence at Sauternes wine estates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 2909–2918. 10.1128/AEM.03627-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco P., Viana T., Albergaria H., Arneborg N. (2015). Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae induce alterations in the intracellular pH, membrane permeability and culturability of Hanseniaspora guilliermondii cells. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 205, 112–118. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brice C., Cubillos F. A., Dequin S., Camarasa C., MartõÂnez C. (2018). Adaptability of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts to wine fermentation conditions relies on their strong ability to consume nitrogen. PLoS ONE 13:e0192383. 10.1371/journal.pone.0192383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan R. L., Solberg M. (1972). Interaction of sodium nitrite, oxygen and pH on growth of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Food Sci. 37,81–85. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1972.tb03391.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Callejon R. M., Clvijo A., Ortigueira P., Troncoso A. M., Paneque P., Morales M. L. (2016). Volatile and sensory profile of organic red wines produced by different selected autochthonous and commercial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Anal. Chem. Acta 660, 68–75. 10.1016/j.aca.2009.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capece A., Pietrafesa R., Romano P. (2011). Experimental approach for target selection of wild wine yeasts from spontaneous fermentation of “Inzolia” grapes. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27, 2775–2783. 10.1007/s11274-011-0753-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capece A., Romaniello R., Siesto G., Romano P. (2012). Diversity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts associated to spontaneously fermenting grapes from an Italian “heroic vine-growing area”. Food Microbiol. 31, 159–166. 10.1016/j.fm.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilleja D. E. M., Tapia J. A. A., Medrano S. M. A., Hernández Iturriaga M., Soto Muñoz L., Martínez Peniche R. A. (2017). “Growth kinetics for the selection of yeast strains for fermented beverages” in the Yeast - Industrial Applications, ed Morato A. (London: Intech Open; ), 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ciani M., Capece A., Comitini F., Canonico L., Siesto G., Romano P. (2016). Yeast interactions in inoculated wine fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 7:555. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocolin L., Pepe V., Comitini F., Comi G., Ciani M. (2004). Enological and genetics traits of Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolated from former and modern wineries. FEMS Yeast Res. 3, 237–245. 10.1016/j.femsyr.2004.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csoma H., Zakany N., Capece A., Romano P., Sipiczki M. (2010). Biological diversity of Saccharomyces yeasts of spontaneously fermenting wines in four wine regions: comparative genotypic and phenotypic analysis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 140, 239–248. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J., Huang X., Zhang L., Zhao N., Yang D., Zhang K. (2009). Tolerance and stress response to ethanol in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 253–263. 10.1007/s00253-009-2223-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli C. M., Edinger W. D., Mitrakul C. M., Henick-Kling T. (1998). Dynamics of indigenous and inoculated yeast populations and their effect on the sensory character of riesling and chardonnay wines. J. Appl. Microbiol. 85, 779–789. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00521.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteve-Zarzoso B., Belloch C., Uruburu F., Querol A. (1999). Identification of yeast by RFLP analysis of the 5.8 rRNA and the two ribosomal internal transcribed spacers. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49, 329–337. 10.1099/00207713-49-1-329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleet G. H. (2003). Yeast interactions and wine flavor. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 86,11–22. 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00245-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frezier V., Dubourdieu D. (1992). Ecology of yeast strain Saccharomyces cerevisiae during spontaneous fermentation in a Bordeaux winery. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 53, 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ríos E., Gutiérrez A., Salvadó Z., Arroyo-López F. N., Guillamona J. M. (2014). The fitness advantage of commercial wine yeasts in relation to the nitrogen concentration, temperature, and ethanol content under microvinification conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 704–713. 10.1128/AEM.03405-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard M. R. (2008). Quantifying the complexities of Saccharomyces cerevisiae's ecosystem engineering via fermentation. Ecology 89, 2077–2082. 10.1890/07-2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granchi L., Carobbi M., Guerrini S., Vincenzini M. (2006). “Rapid enumeration of yeasts during wine fermentation by the combined use of thoma chamber and epifluorescence microscopy,” in: XXIX Congresso mopndiale della Vigna e del Vino, Logroño, Spagna, 25-30 Giugno 2006, OIV, Resúmenes de Comunicaciones (Vol. 2). 230–232. [Google Scholar]

- Granchi L., Ganucci D., Messini A., Rosellini D., Vincenzini M. (1998). Dynamics of yeast populations during the early stages of natural fermentation for the production of Brunello di Montalcino wines. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 36, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Granchi L., Ganucci D., Viti C., Giovannetti L., Vincenzini M. (2003). Saccharomyces cerevisiae biodiversity in spontaneous commercial fermentations of grape musts with adequate and inadequate assimilable-nitrogen content. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 36, 54–58. 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01263.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillamón J. M., Barrio E., Querol A. (1996). Characterization of Wine Yeast Strains of the Saccharomyces genus on the basis of molecular markers: relationships between genetic distance and geographic or ecological origin. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 19, 122–132. 10.1016/S0723-2020(96)80019-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez A. R., López R., Santamaría P., Sevilla M. J. (1997). Ecology of inoculated and spontaneous fermentations in Rioja (Spain) musts, examined by mitochondrial DNA restriction analysis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 36, 241–245. 10.1016/S0168-1605(97)01258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutièrrez A. R., Santamarìa R., Epifanio S., Garijo P., Lopez R. (1999). Ecology of spontaneous fermentation in one winery during 5 consecutive years. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 29, 411–415. 10.1046/j.1472-765X.1999.00657.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl D. L., Clark A. G. (1997). Principles of Population Genetics. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques D., Alonso-del-Real J., Querol A., Balsa-Canto E. (2018). Saccharomyces cerevisiae and S. kudriavzevii synthetic wine fermentation performance dissected by predictive modeling. Front. Microbiol. 9:88 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs C. J., van Vuuren H. J. J. (1991). Effects of different killer yeasts on wine fermentations. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 42, 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Knight S., Klaere S., Fedrizzi B., Goddard M. R. (2015). Regional microbial signatures positively correlate with differential wine phenotypes: evidence for a microbial aspect to terroir. Sci. Rep. 5:14233. 10.1038/srep14233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre D., Gabrie V., Vayssier V., Fontagné-Faucher C. (2002). Simultaneous HPLC determination of sugars, organic acids and ethanol in sourdough process. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 5, 407-414. 10.1006/fstl.2001.0859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopandic K., Gangl H., Wallner E., Tscheik G., Leitner G., Querol A., et al. (2007). Genetically different wine yeasts isolated from Austrian vine-growing regions influence wine aroma differently and contain putative hybrids between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces kudriavzevii. FEMS Yeast Res. 7, 953–965. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00240.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiniuk J. T., Pacheco B., Russell G., Tong S., Backstrom I., Measday V. (2016). Impact of commercial strain use on Saccharomyces cerevisiae population structure and dynamics in Pinot Noir vineyards and spontaneous fermentations of a Canadian winery. PLoS ONE 11:e0160259. 10.1371/journal.pone.0160259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado L., Sturm M. E., Rojo M. C., Ciklic I., Martínez C., Combina M. (2011). Biodiversity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae populations in Malbec vineyards from the “Zona Alta del Río Mendoza” region in Argentina. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 151, 319–326. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Whittle P., Goddard M. R. (2018). From vineyard to winery: a source map of microbial diversity driving wine fermentation. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 75–84. 10.1111/1462-2920.13960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen P., Arnebor N. (2003). Characterization of early deaths of non-Saccharomyces yeasts in mixed cultures with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch. Microbiol. 180, 257–263. 10.1007/s00203-003-0585-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlić S., Vojvoda T., Babić K. H, Arroyo-López F. N., Jeromel A., Kozina B., et al. (2010). Diversity and oenological characterization of indigenous Saccharomyces cerevisiae associated with Zilavka grapes. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 26, 1483–1489. 10.1007/s11274-010-0323-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oxman E., Alon U., Dekel E. (2008). Defined order of evolutionary adaptations: experimental evidence. Evolution 62, 1547–1554. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00397.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez F., Ramìrez M., Regodòn J. A. (2001). Influence of killer strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on wine fermentation. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 79, 393–399. 10.1023/A:1012034608908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Torrado R., Rantsiou K., Perrone B., Navarro-Tapia E., Querol A., Cocolin L. (2017). Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains: insight into the dominance phenomenon. Sci. Rep. 7:43603. 10.1038/srep43603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone B., Giacosa S., Rolle L., Cocolin L., Rantsiou K. (2013). Investigation of the dominance behavior of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains during wine fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 165, 156–162. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramateftaki P. V., Lanaridis P., Typas M. A. (2000). Molecular identification of wine yeasts at species or strain level: a case study with strains from two vine-growing areas of Greece. J. Appl. Microbiol. 89, 236–248. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01102.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius I. S. (2000). Tailoring wine yeast for the new millennium: Novel approaches to the ancient art of winemaking. Yeast 16, 675–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querol A., Fleet G. H. (2006). Yeasts in food and beverages. Berlin; Heidelberg:Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Querol A., Barrio E., Ramon D. (1994). Population dynamics of wine yeast strains in natural fermentations. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 21, 315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RESOLUTION OIV-OENO 370 (2012). Guidelines for the Characterization of Wine Yeasts of the Genus Saccharomyces Isolated from Vitivinicultural Environment. Available online at: http://www.oiv.int/public/medias/1429/oiv-oeno-370-2012-en.pdf.

- Romano P., Fiore C., Paraggio M., Caruso M., Capece A. (2003). Function of yeast species and strains in wine flavour. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 86, 169–180. 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00290-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabate J., Cano J., Esteve-Zarzoso B., Guillamón J. M. (2002). Isolation and identification of yeasts associated with vineyard and winery by RFLP analysis of ribosomal genes and mitochondrial DNA. Microbiol. Res. 157, 267–274. 10.1078/0944-5013-00163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabate J., Cano J., Querol A., Guillamon J. M. (1998). Diversity of Saccharomyces strains in wine fermentations: analysis for two consecutive years. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 26, 452–455. 10.1046/j.1472-765X.1998.00369.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvadó Z., Arroyo-López F. N., Barrio E., Querol A., Guillamón J. M. (2011). Quantifying the individual effects of ethanol and temperature on the fitness advantage of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Microbiol. 28, 1155–1161. 10.1016/j.fm.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A., Gerbi V., Redoglia M. (1987). A rapid HPLC method for separation and determination of major organic acids in grape musts and wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 38, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Schuller D., Alves H., Dequin S., Casal M. (2005). Ecological survey of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains from vineyards in the Vinho Verde region of portugal. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 51, 167–177. 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller D., Cardoso F., Sousa S., Gomes P., Gomes A. C., Santos M. A. S., et al. (2012). Genetic diversity and population structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains isolated from different grape varieties and winemaking regions. PLoS ONE 7:e32507. 10.1371/journal.pone.0032507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon S. E., Weaver W. (1963). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sneath P. H. A., Sokal R. R. (1973). Numerical Taxonomy. The Principles and Practice of Numerical Classification. San Francisco,CA: W.H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen I. A., Bernaerts K., Dens E. J., Geeraerd A. H., Van Impe J. F. (2004). Predictive modelling of the microbial lag phase: a review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 94,137–159. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofalo R., Perpetuini G., Schirone M., Fasoli G., Aguzzi I., Corsetti A., et al. (2013). Biogeographical characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine yeast by molecular methods. Front. Microbiol. 4:166. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torija M., Rozès N., Poblet M., Guillamón J. M., Mas A. (2001).Yeast population dynamics in spontaneous fermentations: comparison between two different wine-producing areas over a period of three years. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 79, 345–352. 10.1023/A:1012027718701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versavaud A., Courcoux P., Roulland C., Dulau L., Hallet J. N. (1995). Genetic diversity and geographical distribution of wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains from the wine-producing area of Charentes, France. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 3521–3529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezinhet F., Hallet J. N., Valade M., Poulard A. (1992). Ecological survey of wine strains by molecular methods of identification. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 43, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Villanova M., Sieiro C. (2006). Contribution by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae yeast to fermentative flavor compounds in wines from cv. Albariño. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33, 929–933. 10.1007/s10295-006-0162-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]