Abstract

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is the most common pediatric cancer in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and also occurs frequently among adolescents and young adults (AYAs), often associated with HIV. Treating BL in SSA poses particular challenges. Although highly effective, high-intensity cytotoxic treatments used in resource-rich settings are usually not feasible, and lower-intensity continuous infusion approaches are impractical. In this article, based on evidence from the region, we review management strategies for SSA focused on diagnosis and use of prephase and definitive treatment. Additionally, potentially better approaches for risk stratification and individualized therapy are elaborated. Compared with historical very low-intensity approaches, the relative safety, feasibility, and outcomes of regimens incorporating anthracyclines and/or high-dose systemic methotrexate for this population are discussed, along with requirements to administer such regimens safely. Finally, research priorities for BL in SSA are outlined including novel therapies, to reduce the unacceptable gap in outcomes for patients in SSA vs high-income countries (HICs). Sustained commitment to incremental advances and innovation, as in cooperative pediatric oncology groups in HICs, is required to transform care and outcomes for BL in SSA through international collaboration.

Introduction

It is ironic and tragic that patients with Burkitt lymphoma (BL) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have not benefited from discoveries resulting from first identification of BL in Uganda in the 1950s.1 Children in Kampala contributed to the discovery of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV),2 the MYC oncogene,3 and multiagent chemotherapy to cure aggressive hematologic malignancies.4 Although BL in SSA was one of the most curable cancers worldwide in the 1960s, outcomes today remain the same, whereas >90% of pediatric BL is cured in high-income countries (HICs).

This is due to weak health care systems and low cancer literacy, which contribute to late diagnosis, and inability to administer and support patients through high-intensity cytotoxic treatment. As a result, tumors are larger, disease stage higher, achievable treatment intensity lower, and treatment-related mortality higher in SSA than in HICs, all of which reduce long-term survival.

These challenges are compounded by scarce high-grade evidence to inform BL care in SSA, despite important contributions by several pediatric groups. Consequently, there is tremendous heterogeneity in BL management and reported outcomes. Here, we review the existing regional literature for BL, emphasize elements of optimal management, and highlight future directions for BL clinical research in SSA.

Case 1

A 9-year-old, HIV− boy in Lilongwe, Malawi presents with a 4-week history of an abdominal mass. He is malnourished with a Lansky performance score of 50. His hemoglobin is 10.0 g/dL with otherwise normal blood counts, serum albumin is 3.0 g/dL, and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is 3 times the upper limit of normal.

Diagnosis

The first issue for this child with a typical pediatric BL presentation is to establish the diagnosis. This is challenging in SSA, given limited pediatric surgery and interventional radiology, as well as limited pathology, usually without flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, fluorescence in situ hybridization, and cytogenetics.5,6 However, although it is difficult to achieve a level of diagnostic certainty for BL in SSA comparable to HICs, an accurate diagnosis can often still be made.7,8 Moreover, even for typical clinical presentations, committing children to cytotoxic treatment mandates an attempt to confirm they have BL, given the perils of clinical cancer diagnosis in SSA.9,10

At a minimum, fine needle aspiration (FNA), which is discouraged for lymphoma diagnosis in the United States, can confirm BL in the correct clinical context in SSA.8 Diagnostic accuracy of FNA is enhanced if there is consensus review by >1 pathologist and if accompanying clinical data informs the interpretation. One mechanism for achieving “enhanced” FNA interpretation is through clinicopathologic conferences, which can even be conducted internationally with relatively modest infrastructure requirements using various telepathology systems.11-13 Improvements in diagnostic accuracy can also be achieved through flow cytometry, using ubiquitous instruments for measuring CD4 counts in HIV programs, although additional reagents, validation, and quality control are needed. Tissue biopsy and limited immunohistochemistry can also support accurate BL diagnosis in SSA.7,11

Given current interest in liquid biopsies for cancer screening, diagnosis, and therapeutic monitoring, it is worth noting that EBV in peripheral blood of patients with EBV-associated malignancies is largely tumor-derived,14 and could represent one of the most implementable circulating cell-free DNA technologies for cancer detection and monitoring in low-income countries (LICs).15 Although more sophisticated immunoglobulin sequencing approaches are under investigation,16 EBV DNA has existing commercial assays which can be implemented in SSA using available instruments for measuring HIV RNA.17 In Malawi, plasma EBV DNA measurement has been used to support BL diagnosis,18 not as a stand-alone tool but as an adjunct with other clinical and pathologic data to avoid confusion with other lymphoma subtypes that are also associated with EBV (Hodgkin, plasmablastic, extranodal NK/T-cell),19,20 as well as EBV reactivation in nonmalignant diseases like malaria.

Given unavailability of molecular tools to definitively establish a BL diagnosis in most SSA settings,21 deriving and validating a composite diagnostic score for molecularly confirmed BL in SSA would have tremendous regional value. Such a scoring system would include data that can be easily generated locally, for example, age, clinical site, cytologic features, histologic features, immunophenotype, LDH, and plasma EBV DNA. Such a scoring system would include clear delineation of incremental costs needed to achieve incrementally higher diagnostic certainty, allowing judicious resource utilization in SSA where per capita health expenditure may be <$50 annually (vs >$9000 in the United States).22 For instance, a child with a jaw mass and typical BL cytology in Malawi confirmed by 2 pathologists does not require additional studies to be justifiably treated for BL, even if this would be unacceptable in HICs.

Baseline evaluation and risk stratification

A core oncology treatment principle is to tailor treatment intensity using baseline prognostic factors. This may be more important in SSA than HICs, because risks of overtreatment are higher, due to high opportunistic infection burden, frequent co-occurrence of HIV and malnutrition, and poor supportive care. However, accurate risk stratification is challenging in SSA, given crude, highly operator-dependent, nonreproducible modalities used to stratify patients. Patients with BL in SSA are frequently staged using physical examination, chest radiograph, abdominal ultrasound, and cerebrospinal fluid evaluation. Bone marrow evaluation and computed tomography (CT) may be done if available. Advanced imaging like CT with positron emission tomography (PET), which are standard staging modalities in HICs, are usually not available.

Because of these limitations, patients with BL in SSA are often understaged relative to HICs, and reproducibility of staging across SSA centers is poor. This could be addressed through uniform regional implementation of simple, quantifiable, point-of-care peripheral blood assays to enhance comparability of baseline prognostic features across cohorts. Foremost among these would be LDH and EBV DNA, which have strong, continuous relationships with prospective outcomes.18,23 To illustrate, the International Prognostic Index (IPI) used in HICs to predict outcomes among adults with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) retains prognostic value in Malawi.24,25 However, it is suboptimal due to dichotomized LDH as normal/abnormal in a population for whom LDH is almost always elevated, given more advanced disease than HIC cohorts, and points assigned for clinical stage and extranodal involvement which are imprecise in SSA.24,25 Based on existing data and these considerations, an ideal simplified prognostic model for BL in SSA might include just performance status with nondichotomized LDH and/or EBV DNA, and would likely be more accurate and reproducible, and likely more reflective of true disease extent, but this requires validation in large regional cohorts. Such a simplified risk stratification scheme could obviate the need for routine CT and/or bone marrow assessment, which require time, expense, and expertise to perform and interpret, are of variable quality, cause discomfort to sick patients, and rarely change clinical management in SSA. Prognostic scores using data generated in real time to discriminate patients into clinically meaningful groups have been a cornerstone of lymphoma care in HICs for decades,26,27 and similar derivation and validation efforts are needed in SSA rather than simply transposing HIC approaches.

Prephase treatment

After confirming the diagnosis and completing baseline evaluation, or simultaneously, the next priority is to mitigate risk of early death upon cytotoxic initiation. Fulminant tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) is fatal in many SSA settings, given limited facilities for renal replacement therapy and rasburicase unavailability. Prevention of TLS with carefully phased treatment initiation is therefore paramount. In very sick patients (Lansky performance status ≤50 or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] performance status ≥3), we favor a graduated scheme of prednisone for 5 to 7 days, followed by prephase COP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone), before initiating definitive treatment 5 to 7 days later, as is the standard approach for pediatric BL in HICs.28 This approach can “rescue” patients felt to be too sick for cytotoxic treatment, and provides ample time for hydration, transfusion, and other stabilization measures before bulky, proliferative tumors are subjected to multiagent chemotherapy. For less sick patients, definitive treatment can be initiated more rapidly, 5 to 7 days after prephase COP, or even prednisone alone. Allopurinol is available in most SSA settings, and we administer this continuously throughout the prephase period.

Definitive treatment

High-intensity or continuous infusion regimens for treating BL in HICs are difficult to apply in most SSA settings, due to logistical challenges and treatment-related toxicity. Strategies in SSA fall into 3 broad categories: low-intensity approaches, higher-intensity approaches incorporating anthracyclines, and higher-intensity approaches incorporating high-dose methotrexate (Table 1). We are unaware of randomized studies comparing these strategies in SSA, and efforts to apply regimens incorporating both anthracyclines and high-dose methotrexate as in HICs have been unsuccessful. Regardless of approach, poor outcomes are mainly due to relapsed/refractory BL, although treatment-related mortality from infectious complications and/or TLS predictably increases as treatment intensity is escalated. As shown in Table 2, published data reporting efficacy and safety of these approaches with few exceptions consist of observational cohorts at single centers, with wide variation in BL diagnostic criteria, proportion of BL patients excluded, reasons for exclusion, and completeness of follow-up. These issues can have major influence on reported outcomes, making regional BL literature difficult to interpret, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Commonly used first-line chemotherapy regimens for BL in sub-Saharan Africa

| Regimen | Reference | Drugs* | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prephase | |||

| 39 | Cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 IV; day 1 | Children with malnutrition received cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 | |

| 40 | Methotrexate 12 mg IT; day 1 | ||

| 23 | Cyclophosphamide 300-400 mg/m2 IV; day 1 | ||

| Vincristine 1 mg/m2 (max, 2 mg) IV; day 1 | |||

| Prednisone 1.5 mg/kg PO; days 1-5 | |||

| Low-intensity | |||

| INCTR 03-06 protocol | 33 | Cyclophosphamide 1200 mg/m2 IV; day 1 | 15-d cycles if ANC ≥1.0 × 109 /L and platelets ≥75 × 109/L |

| Vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 (max, 2 mg) IV; day 1 | 3 cycles for low risk (single extra-abdominal site <10 cm) | ||

| Methotrexate 75 mg/m2 IV; day 1 | 6 cycles for high risk (all others) | ||

| Methotrexate 12 mg IT; days 1 and 8 | |||

| Cytarabine 50 mg IT; day 4 | |||

| With anthracyclines | |||

| CHOP | 23 | Cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2 IV; day 1 | 21-d cycles × 6 cycles if ANC ≥1.0 × 109/L and platelets ≥75 × 109 /L |

| Doxorubicin 40 mg/m2 IV; day 1 | |||

| Vincristine 1 mg/m2 (max, 2 mg) IV; day 1 | |||

| Prednisone 1.5 mg/kg PO; days 1-5 | |||

| Methotrexate 12 mg IT; day 1 | |||

| JOOTRH protocol | 35 | Induction-consolidation | |

| Cyclophosphamide 1200 mg/m2 IV; days 1, 8, 15, 22, 28, 35 | |||

| Doxorubicin 60 mg/m2 IV; days 1, 22 | |||

| Vincristine 1.5 mg/m2 IV; days 1, 8, 15, 22, 28, 35 | |||

| Methotrexate 7.5 mg/m2 IT; days 1, 8, 15, 22 | |||

| Prednisone PO tapering dose | |||

| Maintenance | Maintenance | ||

| Cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 IV; day 1 | 28-d cycles × 24 mo | ||

| Vincristine 1.5 mg/m2 IV; day 1 | |||

| Malawi 2012-2014 protocol | 36 | Cyclophosphamide 40 mg/kg (max, 1.6 g) IV; days 1, 15, 28 | Doxorubicin given for only stage III/IV |

| Cyclophosphamide 60 mg/kg (max, 2.4 g) IV; day 8 | |||

| Doxorubicin 60 mg/m2 IV; days 15, 28 | |||

| Vincristine 1.5 mg/m2 (max, 2 mg) IV; days 1, 8, 15, 28 | |||

| Prednisone 60 mg/m2 PO; days 1-5 | |||

| Methotrexate 12.5 mg IT; day 1, 8, 15, 28 | |||

| With high-dose methotrexate | |||

| GFAOP 2001/2009 protocol | 39 | Induction | Induction |

| 40 | Cyclophosphamide 250 mg/m2 IV; days 1-3 | 15-d cycles × 2 cycles administered once (1) ANC ≥ 1.0 × 109 /L or ANC ≥ 0.5 × 109 /L and increasing; and (2) platelets ≥ 100 × 109 /L | |

| Vincristine 1.5 mg/m2 (max, 2 mg) IV; day 1 | Leucovorin given for 12 doses beginning 24 h after methotrexate | ||

| Methotrexate 1-3 g/m2 IV over 3 h; day 1 | Alkaline hydration administered 2 h before and 2 h after methotrexate | ||

| Leucovorin 15 mg/m2 4× daily PO/IV; days 2-4 | Methotrexate 1 g/m2 in 2001 protocol safely escalated to 3 g/m2 in 2009 protocol | ||

| Prednisone 60 mg/m2 PO; days 2-5 | For stage IV with <70% blasts in bone marrow: cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 IV, days 1-2; vincristine 2 mg/m2 IV (max 2 mg) IV, Day 1 | ||

| Methotrexate 12 mg IT; days 2 and 6 | |||

| Consolidation | Consolidation | ||

| Methotrexate 1-3 g/m2 IV over 3 h; day 1 | 2 cycles administered once (1) ANC ≥ 1.0 × 109/L or ANC ≥ 0.5 × 109/L and increasing; and (2) platelets ≥ 100 × 109 /L | ||

| Leucovorin 15 mg/m2 4× daily PO/IV; days 2-4 | Leucovorin given for 12 doses beginning 24 h after methotrexate | ||

| Cytarabine 50 mg/m2 2× daily SC; days 2-6 | Alkaline hydration administered 2 h before and 2 h after methotrexate | ||

| Methotrexate 12 mg IT; day 2 | Methotrexate 1 g/m2 in 2001 protocol safely escalated to 3 g/m2 in 2009 protocol | ||

| Cytarabine 50 mg IT; day 7 |

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; max, maximum; PO, oral; SC, subcutaneous; IT, intrathecal.

Methotrexate IT was age-adjusted below 3 years in all protocols.

Table 2.

Comparison of recent prospective clinical BL studies from sub-Saharan Africa

| Study | Countries | Years | Diagnosis method (%) | Proportion of all cases comprising analytic sample, % | Analytic sample, n | Proportion of analytic sample LTFU, % | Median f/u for analytic sample, mo | Median or mean age, y | HIV+, % | Stage III/IV, % | Median or mean Hb, g/dL | Poor nutrition, % | Poor PS, % | Median LDH, IU/L | CR, % | 1-y OS, % | TRM, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-intensity | |||||||||||||||||

| 32 | Burkina Faso | 2005-2008 | Cytology (75) | 69 | 178 | NR | NR | 7 | 0 | 76 | 9.9 | NR | NR | NR | 47 | 51 | 11 |

| Cameroon | Histology (25) | ||||||||||||||||

| Cote d’Ivoire | |||||||||||||||||

| Madagascar | |||||||||||||||||

| Mali | |||||||||||||||||

| Senegal | |||||||||||||||||

| 33 | Kenya | 2004-2009 | Cytology | NR | 356 | NR | NR | 7 | 5 | 70 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 76 | 67 | 9 |

| Nigeria | |||||||||||||||||

| Tanzania | |||||||||||||||||

| 34 | Malawi | 2010-2012 | Cytology | 72-100 | 70 | 11 | NR | 8 | 3 | 67 | 10.0 | 60 | NR | NR | 81 | 62 | 3-6 |

| With anthracyclines | |||||||||||||||||

| 23 | Malawi | 2013-2015 | Cytology (75) | 82 | 73 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 70 | 10.2 | 34 | 82 | 628 | NR | 40* | 16 |

| Histology (25) | |||||||||||||||||

| + telepathology | |||||||||||||||||

| 35 | Kenya | 2003-2011 | Cytology | 75 | 428 | 31 | NR | 7.5 | 0 | 53 | 10.0 | 20 | NR | 512 | NR | 45 | 22 |

| 36 | Malawi | 2012-2014 | Cytology + telepathology | 69-74 | 58 | 0 | 13 | 7 | 5 | 73 | NR | 43 | NR | NR | 72 | 73 | 12 |

| With high-dose methotrexate | |||||||||||||||||

| 39 | Cameroon | 2001-2004 | Cytology | 89 | 187 | NR | NR | 6 | 0 | 87 | NR | 39 | NR | NR | NR | 56 | NR |

| Madagascar | |||||||||||||||||

| Senegal | |||||||||||||||||

| 41 | Cameroon | 2008-2009 | Cytology (87) | NR | 127 | 3 | NR | 8 | 3 | 85 | 9.8 | 39 | NR | NR | 71 | 61 | 14-24 |

| Histology (5) | |||||||||||||||||

| Clinical (9) | |||||||||||||||||

CR, complete response; f/u, follow-up; Hb, hemoglobin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LTFU, loss to follow-up; NR, not reported; OS, overall survival; PS, performance status; TRM, treatment-related mortality.

Intention-to-treat analysis including deaths prior to cytotoxic treatment initiation.

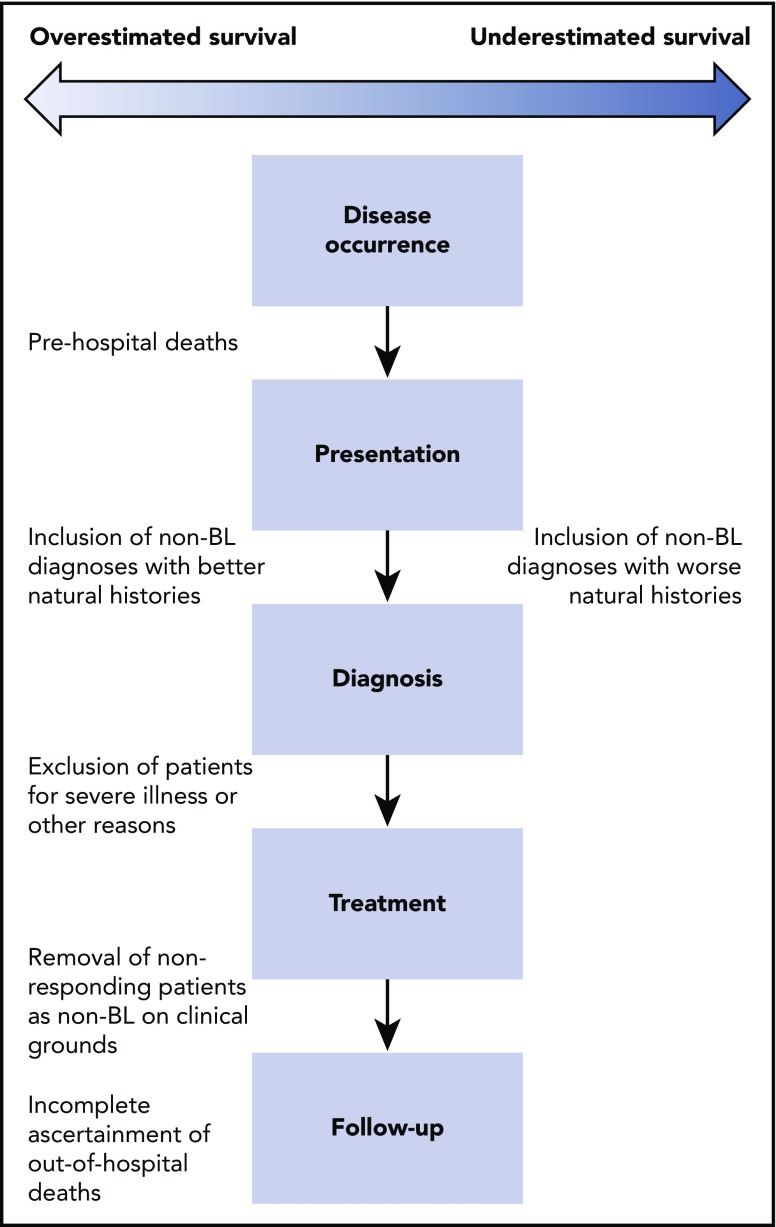

Figure 1.

Illustration of the BL care cascade in sub-Saharan Africa and opportunities to introduce bias into survival estimates.

First, there is inevitable referral bias among BL patients who make it to tertiary centers for care particularly from rural areas. With respect to diagnosis, including other lymphoproliferative disorders with different natural histories from BL, that cannot be distinguished from BL in many SSA settings, affects reported outcomes. Variations in time needed for diagnosis and treatment initiation, as well as subjective exclusion of patients deemed unfit for chemotherapy or other reasons, also affects frequency of early deaths and outcomes. Where pathology is limited, subjective clinical criteria are sometimes applied to support or refute BL diagnosis, including response to chemotherapy. In Malawi, children with abdominal BL diagnosed by FNA who do not respond to chemotherapy are at times empirically diagnosed as having Wilms tumors, with resection and subsequent management according to Wilms tumor protocols. Pathologic reexamination after surgical resection is often not done, although in several instances we have made efforts to rereview these specimens and found them to have immunophenotypes consistent with BL. Removing such refractory BL patients by classifying them as non-BL on clinical grounds will improve observed outcomes. Finally, treatment abandonment and/or loss to follow-up are major issues in SSA, given centralized services, long travel distances, and transportation costs. Importantly, death is a major cause of loss to follow-up in diverse populations in SSA, and censoring patients at loss to follow-up without efforts to trace all outcomes leads to overestimated survival.29-31

Low-intensity approaches

The first attempts to treat BL in SSA involved cyclophosphamide alone or with vincristine and/or low-dose methotrexate, together with intrathecal treatment to prevent leptomeningeal relapse. As shown in Table 1, these strategies have usually resulted in 5% to 10% treatment-related mortality with 50% to 60% 1-year overall survival, although uncertainty about patient selection, as well as completeness and length of follow-up raise questions about how successful such strategies are for most BL patients in SSA.32-34 However, this may currently be the first-line strategy which best optimizes safety and efficacy at least for limited stage BL in SSA. Relapses using this approach are mainly systemic with <5% of relapses being isolated to the central nervous system.33

Anthracycline-based treatment

Most patients in most SSA reports, however, have advanced BL, and due to poor outcomes for this population using low-intensity approaches, recent efforts have intensified therapy by adding anthracyclines. As shown again in Table 1, such approaches increase treatment-related mortality, typically to 15% to 20%, without clearly improving outcomes and 1-year overall survival most often reported as 40% to 50%.23,35,36

Of note, however, investigators in Blantyre, Malawi, have reported improved 1-year disease-free survival from 28% to 66% for stage III/IV BL by adding 2 doses of doxorubicin to a previously described regimen of cyclophosphamide, prednisone, and vincristine, with 12% treatment-related mortality and 1-year overall survival of 73%.36 This represents among the best described treatment experience for this population in SSA. Importantly, of 84 children with BL during the study period, 26 (31%) were excluded, of whom 6 were treated on a different protocol, 10 died at presentation before the diagnosis was confirmed and chemotherapy started, 3 absconded during treatment, and 7 were lost to follow-up.

By comparison, in Lilongwe, Malawi, pediatric BL has recently been treated with 6 cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP), guided by frequent relapse after less intensive treatment. Using this approach, 1-year overall survival in Lilongwe was 71% for stage I/II, 38% for stage III, and 25% for stage IV, in an unselected cohort using intention-to-treat analysis without excluding deaths before cytotoxic treatment, and active tracing to ascertain vital status for nearly all children.23 Accounting for obvious environmental differences, these results are generally consistent with experience from Kenya35 and from the United States in the 1980s, during which the Children’s Cancer Group found that adding daunomycin to cyclophosphamide, vincristine, low-dose methotrexate 300 mg/m2, and prednisone (COMP) for nonlymphoblastic mature B-cell NHL resulted in 57% event-free survival compared with 55% for patients receiving COMP alone.37 On central adjudication of cause of death in Lilongwe, 73% were from relapsed or refractory BL,23 supported by analyses demonstrating 70% of children had detectable EBV DNA at CHOP completion suggesting persistent BL.18 These results suggest treatment failure is mainly due to inability to eradicate advanced BL using CHOP or analogous strategies, rather than excess treatment-related mortality. We have also had difficulty in Lilongwe reproducing Blantyre outcomes using the 28-day protocol with doxorubicin for stage III/IV patients.38

These issues speak again to difficulties comparing treatment experience and outcomes in SSA even within a single country. Taken as a whole, however, these studies suggest anthracycline-based therapy can be considered for BL in SSA, and may be most appropriate for patients with advanced disease.

High-dose methotrexate-based treatment

A more consistently encouraging strategy for advanced BL in SSA may be incorporating high-dose systemic methotrexate. High-dose methotrexate 1-3 g/m2 has long been a standard core component of BL treatment in HICs, in the COPADM/CYM regimen used most typically for children (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, doxorubicin, methotrexate induction followed by cytarabine, methotrexate consolidation), or the hyper-CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone alternating with methotrexate, cytarabine) or CODOX/M-IVAC (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, methotrexate alternating with ifosfamide, etoposide, cytarabine) regimens often used in adults. However, experience with high-dose methotrexate in SSA is variable, with the French-African Pediatric Oncology Group (GFAOP) and others describing successful use of 1 to 3 g/m2,39-41 but other studies reporting excessive treatment-related mortality of 20% to 30%.42,43 Likely, this heterogeneity reflects differences in infrastructure, nursing, and supportive care to administer such doses of systemic methotrexate safely. Capacity for hydration, urinary alkalization, and monitoring vary markedly in SSA, and methotrexate is usually administered in settings where measuring serum drug levels is not possible, but which does not prohibit safe methotrexate administration.

GFAOP efforts in this regard are notable, as this group working across several SSA countries have described the largest experience introducing high-dose methotrexate with requisite supportive care protocols, which they found to be safe and effective at a dose of 1 g/m2 in the GFA 2001 protocol, with 1-year overall survival 56%.39 Encouraged by this, the GFAOP has since developed the GFA 2009 protocol increasing systemic methotrexate dose from 1 to 3 g/m2 with preliminary data demonstrating 1-year overall survival of 61% and treatment-related mortality of 9% at the 3 g/m2 methotrexate dose.40

Notably, while implementing the GFA 2001 protocol, a parallel effort at North African sites with greater pediatric oncology capacity achieved 1-year overall survival of 75% using regimens more closely approximating those used in Europe,39 with high-dose methotrexate and doxorubicin, emphasizing the important relationship between increased cytotoxic intensity and increased survival, which has after all been a guiding principle for BL treatment in HICs historically. Retrospective data from South Africa also suggest applying intensive regimens with anthracyclines and high-dose methotrexate without major modifications is feasible in middle-income countries with sufficient infrastructure and expertise.44,45

Continuous infusion approaches

In HICs, the dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin (EPOCH) chemotherapy regimen has recently gained acceptance as a better tolerated, effective strategy without high-dose methotrexate for treating BL in adults,46 although controversy remains about the suitability of this approach for high-risk BL.47 Some have advocated for its application in SSA, but it is important to acknowledge the many logistical barriers which prohibit continuous infusions in most settings, including access to infusion pumps and central venous catheters, as well as limited overnight staffing to deal with extravasation, pump malfunctions, and other issues which inevitably arise. In Lilongwe, due to poor outcomes particularly among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with BL treated with CHOP, who frequently have EBV− disease,23,44 we have begun treating such patients with a modified EPOCH strategy administering 24-hour doses over 8 hours on 4 successive clinic days, avoiding overnight administration, and with dose adjustment as per the National Cancer Institute protocol. In very early experience, this has been feasible without hematopoietic growth factors using standardized anti-infective prophylaxis (cotrimoxazole, ciprofloxacin, fluconazole), and has seemed promising for NHL subtypes like BL, plasmablastic lymphoma, and primary effusion lymphoma known to have poor outcomes after CHOP. Grade 3/4 neutropenia has occurred in all patients but is manageable in patients with and without HIV, and patients treated to date have completed a median 5 cycles at protocol dose levels typically ranging from −2 to 2 per cycle.46 However, this experience is anecdotal with few patients and limited follow-up.

Rituximab

In most SSA environments, there is a cytotoxic ceiling beyond which dose escalation cannot safely occur. Therefore, targeted agents may have greater importance even than in HICs for BL treatment. Rituximab improves outcomes for aggressive CD20+ B-cell NHL subtypes, including for HIV+ patients with CD4 counts > 50 cells/µL which is the immunologic context in which HIV-associated BL typically occurs,48-51 and including among children and adolescents with BL as demonstrated by the recent intergroup trial.52 Additionally, subcutaneous administration has gained acceptance,53 enhancing feasibility for settings with limited infusion capacity and potentially lowering cost,54 and a biosimilar is commercially available worldwide with pharmacokinetic equivalence compared with the patented formulation.55 However, cost remains an issue even for the biosimilar, with typical wholesale prices for an adult course of treatment being $3000 to $4000 US dollars, substantially exceeding annual per capital health expenditures in most SSA countries. As such, rituximab is usually sporadically applied in the private sector to the very few patients who can afford to purchase it. Apart from feasibility issues, safety and efficacy specifically in SSA have not been demonstrated, where hematopoietic growth factor support is not routine, and where opportunistic infectious complications during B-cell depletion may be higher than HICs. As a result, we and others have felt it important to prospectively assess rituximab in SSA for BL and other B-cell NHL subtypes, with our early experience from Lilongwe being encouraging to date.56 If safe and effective, formal cost-effectiveness evaluation will be important to inform policymakers. Although very costly by SSA standards, an upfront expenditure that substantially increases long-term event-free survival might have comparable cost-effectiveness to lifelong daily antiretroviral therapy (ART) to treat HIV, which has been prioritized as an economically sound intervention in SSA. Moreover, as the movement to achieve universal HIV treatment access has shown, drug prices can be negotiated when there is sufficient demand, political will, and evidence.

Case 2

A 22-year-old young man in Lilongwe, Malawi presents with a 3-week history of a bulky axillary mass. Biopsy including immunohistochemistry demonstrates BL, and he is newly diagnosed with HIV without having been on ART. His CD4 count is 550 cells per µL and HIV RNA is 4.2 log10 copies per mL. He receives 4 cycles of a modified EPOCH regimen with concurrent ART and achieves a partial response. However, treatment is complicated by neutropenia which limits cytotoxic cumulative dose and intensity, and by frequently missed chemotherapy appointments, and he develops tumor progression within 2 months.

HIV-associated BL

In most reports from SSA, HIV prevalence among children with BL is <5%,23,33,34,36,41,57 and when HIV-associated BL occurs, it is usually among AYAs with relatively preserved CD4 counts.45 Treatment of HIV+ patients with BL is generally the same as for HIV− individuals, but neutropenia in settings without reliable hematopoietic growth factor availability is a major challenge.24 ART should not be withheld in SSA during chemotherapy, as is sometimes advocated in HICs to avoid drug-drug interactions,58 as this places patients at unacceptable risk for infectious complications in SSA. Interactions and overlapping toxicities with chemotherapy can be anticipated and managed, and are not so problematic with tenofovir-lamivudine-efavirenz which is currently first-line ART in most of SSA. Zidovudine should be avoided, and more caution and possible empiric chemotherapy dose reduction are needed for patients on protease inhibitor–based treatment, but integrase inhibitor-based regimens are also increasingly available in SSA59 and preferred when possible to minimize chemotherapy interactions.60 Moreover, there is an overwhelming literature demonstrating that earlier, continuous ART is better for individual health and population-level transmission than starting later.61,62 ART might also exert important anti-tumor immunotherapy effects in addition to salutatory effects on HIV.63,64

AYAs

As in HICs, AYAs are understudied and have worse outcomes in SSA than younger children with BL.23,65 Reasons for this are multifactorial including unique disease biology which is frequently EBV−, uncertainty regarding best treatment approaches and whether these should follow pediatric or adult protocols, historical exclusion from clinical trials, and distinct psychosocial issues including poor treatment adherence. In SSA, given young population age structure, lower life expectancy, and general socioeconomic conditions, AYAs also often assume adult responsibilities at younger ages than HICs with greater independence and less family supervision. This may include traveling long distances alone for clinic visits and taking primary responsibility for treatment adherence. Dedicated support services and defined treatment strategies are needed for this challenging and neglected population in SSA.66

Relapsed/refractory BL

Given challenges administering effective first-line treatment of BL in SSA, relapsed/refractory BL is common and hard to address in light of difficulties providing more intensive salvage chemotherapy and high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell rescue. Indeed, relapsed/refractory BL is challenging even in HICs, but effective first-line treatment makes this much rarer than in SSA. Autologous stem cell rescue is available in South Africa,67,68 and many SSA countries have processes for externally referring patients to South Africa or India, but usually these processes are too long and/or unreliable to be a viable option for most patients with relapsed/refractory BL. For the vast majority of patients in SSA, relapsed/refractory BL is fatal. Moderate-intensity salvage chemotherapy regimens can be administered, but achievable cytotoxic intensity in the setting of relapsed/refractory BL typically produces partial responses and symptom alleviation with durations usually measured in months,45,69 emphasizing the need for better first-line treatment to reduce the frequency with which relapsed/refractory BL occurs.

Biology and new approaches

Already, molecular investigations in BL have demonstrated potential therapeutic targets beyond MYC, including B-cell receptor signaling, PI3K, and other dysregulated genes and pathways for which approved agents exist,16,70-73 although these remain economically far out of reach of most SSA countries. Arguably, testing drugs for which there is sufficient preclinical or clinical rationale incorporated into front-line treatment in SSA, given the cytotoxic ceiling imposed by the environment, may be globally impactful and yield new, lower-intensity treatments compared with current international standards of care. Such developments would be important for SSA by outlining viable paths to cure in LICs, and important for HICs by outlining viable paths to cure that avoid short- and long-term toxicities of existing approaches. As in the 1960s, this could again represent opportunities for BL research in SSA to have truly global impact.

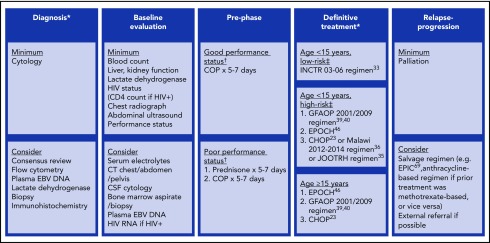

Conclusion

There are more questions than answers in this review, reflecting uncertainties in the BL literature in SSA. Our recommended approach is shown in Figure 2, but unresolved essential questions regarding best approaches to BL diagnosis and treatment in SSA, including long-term outcomes and late treatment effects, demand sustained international commitment to pursue definitive answers through regional collaboration. This is happening via initiatives led by the National Cancer Institute Center for Global Health, and care and research partnerships like GFAOP. By making necessary commitments to this neglected and vulnerable population, we can repay a 50-year-old debt to patients in SSA who contributed to the discovery of BL and fundamental insights into cancer biology. In so doing, we will ensure another 50 years do not elapse with the rest of the world moving forward while outcomes for many patients in SSA remain the same.

Figure 2.

Suggested management for BL in sub-Saharan Africa. *Optimal diagnostic evaluation and definitive treatment will be strongly determined by local expertise, resources, and infrastructure. Treatment on a clinical trial or prospective, longitudinal, cohort study is strongly recommended whenever possible. Concurrent antiretroviral therapy should be administered if HIV-infected. In middle-income countries, high-income country regimens can often be successfully followed. ‡Poor performance status defined as Lansky score ≤50 or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score ≥3. Good performance status defined as all others. ‡Low risk defined as all of the following: stage I/II, no abdominal disease, largest tumor bulk <10 cm, and lactate dehydrogenase <2 times upper limit of normal. High risk defined as all others. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus.

Acknowledgments

S.G. received support from the National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute grants U54CA190152, P20CA210285, P30CA016086-40S4), Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant P30CA016086), University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant P30AI50410), and AIDS Malignancy Consortium (National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant UM1CA121947).

Authorship

Contribution: S.G. and T.G.G. conceived and wrote the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Satish Gopal, UNC Project-Malawi, Private Bag A-104, Lilongwe, Malawi; e-mail: satish_gopal@med.unc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burkitt D. A sarcoma involving the jaws in African children. Br J Surg. 1958;46(197):218-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein MA, Achong BG, Barr YM. Virus particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s lymphoma. Lancet. 1964;1(7335):702-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalla-Favera R, Bregni M, Erikson J, Patterson D, Gallo RC, Croce CM. Human c-myc onc gene is located on the region of chromosome 8 that is translocated in Burkitt lymphoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79(24):7824-7827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziegler JL. Treatment results of 54 American patients with Burkitt’s lymphoma are similar to the African experience. N Engl J Med. 1977;297(2):75-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adesina A, Chumba D, Nelson AM, et al. . Improvement of pathology in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):e152-e157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson AM, Milner DA, Rebbeck TR, Iliyasu Y. Oncologic care and pathology resources in Africa: survey and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(1):20-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naresh KN, Ibrahim HA, Lazzi S, et al. . Diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma using an algorithmic approach--applicable in both resource-poor and resource-rich countries. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(6):770-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naresh KN, Raphael M, Ayers L, et al. . Lymphomas in sub-Saharan Africa--what can we learn and how can we help in improving diagnosis, managing patients and fostering translational research? Br J Haematol. 2011;154(6):696-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amerson E, Woodruff CM, Forrestel A, et al. . Accuracy of clinical suspicion and pathologic diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma in east Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(3):295-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gichuhi S, Macharia E, Kabiru J, et al. . Clinical presentation of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Kenya. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(11):1305-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montgomery ND, Liomba NG, Kampani C, et al. . Accurate real-time diagnosis of lymphoproliferative disorders in Malawi through clinicopathologic teleconferences: a model for pathology services in Sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;146(4):423-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomoka T, Montgomery ND, Powers E, et al. . Lymphoma and pathology in sub-Saharan Africa: current approaches and future directions. Clin Lab Med. 2018;38(1):91-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montgomery ND, Tomoka T, Krysiak R, et al. . Practical successes in telepathology experiences in Africa. Clin Lab Med. 2018;38(1):141-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanakry J, Ambinder R. The biology and clinical utility of EBV monitoring in blood. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;391:475-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan KCA, Woo JKS, King A, et al. . Analysis of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA to screen for nasopharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(6):513-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lombardo KA, Coffey DG, Morales AJ, et al. . High-throughput sequencing of the B-cell receptor in African Burkitt lymphoma reveals clues to pathogenesis. Blood Adv. 2017;1(9):535-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abbott Laboratories. RealTime EBV assay. https://www.molecular.abbott/int/en/products/infectious-disease/realtime-ebv. Accessed 21 March 2018.

- 18.Westmoreland KD, Montgomery ND, Stanley CC, et al. . Plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA for pediatric Burkitt lymphoma diagnosis, prognosis and response assessment in Malawi. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(11):2509-2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westmoreland KD, Stanley CC, Montgomery ND, et al. . Hodgkin lymphoma, HIV, and Epstein-Barr virus in Malawi: longitudinal results from the Kamuzu Central Hospital Lymphoma study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomoka T, Powers E, van der Gronde T, et al. . Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma in Malawi: a report of three cases. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dave SS, Fu K, Wright GW, et al. ; Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project. Molecular diagnosis of Burkitt’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(23):2431-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The World Bank. Health expenditure per capita. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator. Accessed 21 March 2018.

- 23.Stanley CC, Westmoreland KD, Heimlich BJ, et al. . Outcomes for paediatric Burkitt lymphoma treated with anthracycline-based therapy in Malawi. Br J Haematol. 2016;173(5):705-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gopal S, Fedoriw Y, Kaimila B, et al. . CHOP chemotherapy for aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma with and without HIV in the antiretroviral therapy era in Malawi. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Painschab M, Kasonkanji E, Zuze T, et al. . DLBCL outcomes in Malawi: effect of HIV and derivation of a simplified prognostic score. Paper to be presented at American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; 1-5 June 2018; Chicago, Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- 26.International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):987-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin’s disease. International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(21):1506-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patte C, Philip T, Rodary C, et al. . Improved survival rate in children with stage III and IV B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia using multi-agent chemotherapy: results of a study of 114 children from the French Pediatric Oncology Society. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4(8):1219-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanley CC, Westmoreland KD, Itimu S, et al. . Quantifying bias in survival estimates resulting from loss to follow-up among children with lymphoma in Malawi. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semeere A, Freeman E, Wenger M, et al. . Updating vital status by tracking in the community among patients with epidemic Kaposi sarcoma who are lost to follow-up in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, Spycher BD, Sidle J, et al. ; IeDEA East Africa, West Africa and Southern Africa. Correcting mortality for loss to follow-up: a nomogram applied to antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med. 2011;8(1):e1000390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Traoré F, Coze C, Atteby JJ, et al. . Cyclophosphamide monotherapy in children with Burkitt lymphoma: a study from the French-African Pediatric Oncology Group (GFAOP). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(1):70-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ngoma T, Adde M, Durosinmi M, et al. . Treatment of Burkitt lymphoma in equatorial Africa using a simple three-drug combination followed by a salvage regimen for patients with persistent or recurrent disease. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(6):749-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Depani S, Banda K, Bailey S, Israels T, Chagaluka G, Molyneux E. Outcome is unchanged by adding vincristine upfront to the Malawi 28-day protocol for endemic Burkitt lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(11):1929-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buckle G, Maranda L, Skiles J, et al. . Factors influencing survival among Kenyan children diagnosed with endemic Burkitt lymphoma between 2003 and 2011: A historical cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(6):1231-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molyneux E, Schwalbe E, Chagaluka G, et al. . The use of anthracyclines in the treatment of endemic Burkitt lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2017;177(6):984-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sposto R, Meadows AT, Chilcote RR, et al. . Comparison of long-term outcome of children and adolescents with disseminated non-lymphoblastic non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with COMP or daunomycin-COMP: A report from the Children’s Cancer Group. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;37(5):432-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westmoreland KD, El-Mallawany NK, Kazembe P, Stanley CC, Gopal S. Dissecting heterogeneous outcomes for paediatric Burkitt lymphoma in Malawi after anthracycline-based treatment [published online ahead of print 17 July 2017]. Br J Haematol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harif M, Barsaoui S, Benchekroun S, et al. . Treatment of B-cell lymphoma with LMB modified protocols in Africa--report of the French-African Pediatric Oncology Group (GFAOP). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(6):1138-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bouda C, Traore F, Atteby JJ, et al. . A multicenter study for treatment of children with Burkitt lymphoma in sub-Saharan paediatric units: a study of the Groupe Franco-Africain D’Oncologie Pediatrique (GFAOP) [abstract]. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(S4):S156-S157. Abstract O-045. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hesseling PB, Njume E, Kouya F, et al. . The Cameroon 2008 Burkitt lymphoma protocol: improved event-free survival with treatment adapted to disease stage and the response to induction therapy. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;29(2):119-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hesseling PB, Broadhead R, Molyneux E, et al. . Malawi pilot study of Burkitt lymphoma treatment. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;41(6):532-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hesseling P, Broadhead R, Mansvelt E, et al. . The 2000 Burkitt lymphoma trial in Malawi. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44(3):245-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stefan DC, Lutchman R. Burkitt lymphoma: epidemiological features and survival in a South African centre. Infect Agent Cancer. 2014;9(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sissolak G, Seftel M, Uldrick TS, Esterhuizen TM, Mohamed N, Kotze D. Burkitt’s lymphoma and B-cell lymphoma unclassifiable with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt’s lymphoma in patients with HIV: outcomes in a South African public hospital. J Glob Oncol. 2016;3(3):218-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dunleavy K, Pittaluga S, Shovlin M, et al. . Low-intensity therapy in adults with Burkitt’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(20):1915-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobson C, LaCasce A. How I treat Burkitt lymphoma in adults. Blood. 2014;124(19):2913-2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guech-Ongey M, Simard EP, Anderson WF, et al. . AIDS-related Burkitt lymphoma in the United States: what do age and CD4 lymphocyte patterns tell us about etiology and/or biology? Blood. 2010;116(25):5600-5604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barta SK, Xue X, Wang D, et al. . Treatment factors affecting outcomes in HIV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphomas: a pooled analysis of 1546 patients. Blood. 2013;122(19):3251-3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alwan F, He A, Montoto S, et al. . Adding rituximab to CODOX-M/IVAC chemotherapy in the treatment of HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma is safe when used with concurrent combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2015;29(8):903-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noy A, Lee JY, Cesarman E, et al. ; AIDS Malignancy Consortium. AMC 048: modified CODOX-M/IVAC-rituximab is safe and effective for HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma. Blood. 2015;126(2):160-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Minard-Colin V, Auperin A, Pillon M, et al. . Results of the randomized Intergroup trial Inter-B-NHL Ritux 2010 for children and adolescents with high-risk B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) and mature acute leukemia (B-AL): evaluation of rituximab (R) efficacy in addition to standard LMB chemotherapy (CT) regimen [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 15). Abstract 10507. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Assouline S. Subcutaneous rituximab-a meaningful advance in care. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(6):e248-e249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mihajlović J, Bax P, van Breugel E, et al. . Microcosting study of rituximab subcutaneous injection versus intravenous infusion. Clin Ther. 2017;39(6):1221-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gota V, Karanam A, Rath S, et al. . Population pharmacokinetics of RedituxTM, a biosimilar rituximab, in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78(2):353-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gopal S, Kaimila B, Kasonkanji E, et al. . Rituximab in Malawi: early results from a phase II clinical trial. Paper presented at International Conference on Malignancies in HIV/AIDS; 23-24 October 2017; Bethesda, Maryland: https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/oham/hiv-aids-research/oham-research/international-conference/icmaoi-2017.pdf. Accessed 21 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Orem J, Mulumba Y, Algeri S, et al. . Clinical characteristics, treatment and outcome of childhood Burkitt’s lymphoma at the Uganda Cancer Institute. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105(12):717-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Little RF, Dunleavy K. Update on the treatment of HIV-associated hematologic malignancies. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:382-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.World Health Organization. New high-quality antiretroviral therapy to be launched in South Africa, Kenya and over 90 low- and middle-income countries at reduced price. http://www.who.int/hiv/mediacentre/news/high-quality-arv-reduced-price/en/. Accessed 21 March 2018.

- 60.Torres HA, Rallapalli V, Saxena A, et al. . Efficacy and safety of antiretrovirals in HIV-infected patients with cancer. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(10):O672-O679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.INSIGHT START Study Group; Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, et al. . Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. ; HPTN 052 Study Team. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):830-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gopal S, Patel MR, Achenbach CJ, et al. . Lymphoma immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in the center for AIDS research network of integrated clinical systems cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):279-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amengual JE, Zhang X, Ibrahim S, Gardner LB. Regression of HIV-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in response to antiviral therapy alone. Blood. 2008;112(10):4359-4360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kahn JM, Ozuah NW, Dunleavy K, Henderson TO, Kelly K, LaCasce A. Adolescent and young adult lymphoma: collaborative efforts toward optimizing care and improving outcomes. Blood Adv. 2017;1(22):1945-1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davies MA, Hamlyn E. HIV and adolescents: challenges and opportunities. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2018;13(3):167-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gopal S, Wood WA, Lee SJ, et al. . Meeting the challenge of hematologic malignancies in sub-Saharan Africa. Blood. 2012;119(22):5078-5087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Participating transplant centers. https://www.cibmtr.org/About/WhoWeAre/Centers/Pages/index.aspx. Accessed 11 May 2018.

- 69.Kaimila B, van der Gronde T, Stanley C, et al. . Salvage chemotherapy for adults with relapsed or refractory lymphoma in Malawi. Infect Agent Cancer. 2017;12(1):45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Greenough A, Dave SS. New clues to the molecular pathogenesis of Burkitt lymphoma revealed through next-generation sequencing. Curr Opin Hematol. 2014;21(4):326-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmitz R, Young RM, Ceribelli M, et al. . Burkitt lymphoma pathogenesis and therapeutic targets from structural and functional genomics. Nature. 2012;490(7418):116-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Love C, Sun Z, Jima D, et al. . The genetic landscape of mutations in Burkitt lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44(12):1321-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dunleavy K, Little RF, Wilson WH. Update on Burkitt lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30(6):1333-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]