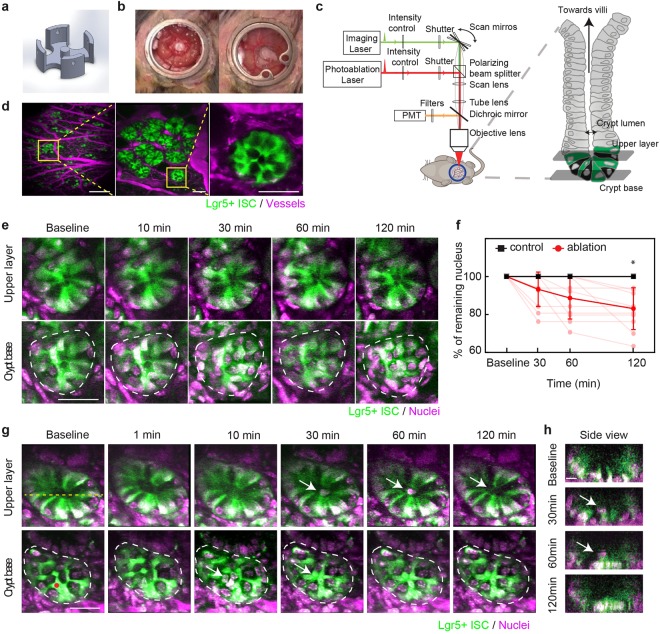

Figure 1.

Rapid clearance of local damage after femtosecond laser ablation in a mouse small intestinal crypt. (a) Schematic of 3D-printed insert that supports intestine in abdominal window. (b) Photos of abdominal window before (left) and after (right) closing with cover glass in a mouse. (c) Schematic (modified from Chen et al.25) of two-photon microscope showing two different laser paths used for both imaging and ablation. (d) In vivo two-photon microscopy images of a crypt at different magnifications in Lgr5-GFP mice expressing GFP in stem cells at the crypt base (green). Vessels are labeled with injected Texas Red dextran (magenta). Yellow boxes indicate magnified areas. Scale bars: 500 µm (left), 50 µm (middle and right). (e) Time-lapse images showing two different imaging planes in a crypt over 2 hours. Green indicates GFP. To label nuclei, Hoechst (magenta) was injected topically. Dashed white lines indicates the border of the crypt base. Scale bar: 30 µm. (f) Number of nuclei in crypt base after ablation (red, 11 crypts) and control (black, 5 crypts). Individual (light points) and averaged numbers displayed as a percentage of initial number. *Multiple t-tests with Holm-Šídák, p = 0.005. (g) Time-lapse images of femtosecond laser ablation of one Lgr5-GFP cell in a crypt at two image planes. Red dot indicates position of ablation laser focus. White arrow indicates cellular debris from the ablation which moved from crypt base towards the villi. Scale bar: 30 µm. (h) Side view at line indicated in (g). Scale bar: 10 µm.