Abstract

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) of the central nervous system is a rare entity of unknown etiology and a diagnostic dilemma for radiologists. We report a case of meningeal IMT occurring in a 15-year-old boy. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a large homogeneously enhancing extra-axial mass in left parietal region. Mass was resected en bloc and histopathological examination revealed the lesion to be composed of plasma cells, lymphocytes admixed with histiocytes, and spindle cells without any atypical cells, characteristic of IMT. This case emphasizes the need to consider IMT in the differential diagnosis of tumorlike intracranial meningeal lesions.

KEYWORDS: Meninges, myofibroblastic tumor, pseudotumor

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a rare disease occurring primarily in children and young adults.[1] It has been described under various names such as “inflammatory pseudotumor,” “plasma cell granuloma,” “pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferation,” and “inflammatory myofibroblastic-histiocytic proliferation” as it very much mimics meningeal neoplasms in clinical as well as radiological presentation.[2] IMT can affect any part of the body but is most commonly seen in lung, mesentery, omentum, retroperitoneum, respiratory tract, and genitourinary tract. Primary intracranial involvement is extremely rare, and only few cases have been reported in literature so far. IMT arising from meninges has a relatively high frequency of recurrence and malignant transformation in comparison to other sites of occurrence and hence poor prognosis.

CASE HISTORY

A 15-year-old male patient presented to neurosurgery outpatient section of the hospital with complaints of recent-onset holocranial headache associated with recurrent vomiting and lethargy. There was no history of head injury, seizures, bladder or bowel disturbance, or any visual disturbance. Clinically, patient was conscious and well oriented without any features of cranial nerve involvement or raised intracranial pressure. All routine laboratory tests were within normal limits including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed a well-defined extradural mass lesion in left parietal region, isointense to cortex on T1-weighted image (WI), iso- to hypointense on T2WI, and heterointense on fluid attenuated inversion recovery with moderately restricted diffusion. Postcontrast images showed intense homogeneous enhancement. There was significant perilesional edema and mild midline shift to right side [Figures 1–3].

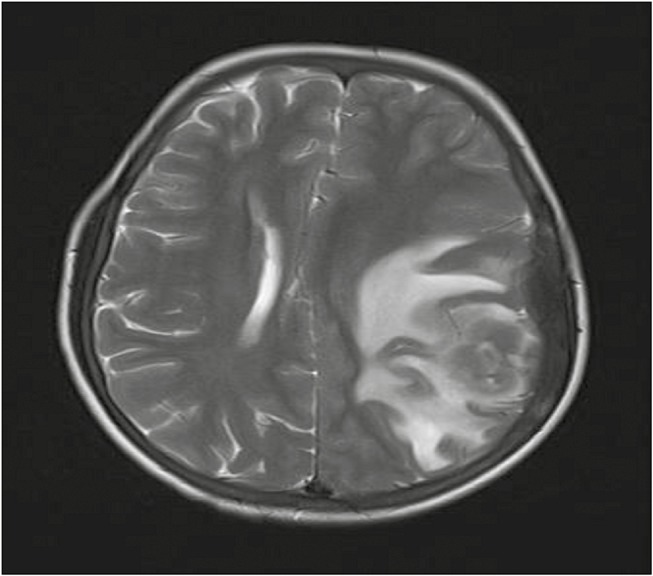

Figure 1.

Preoperative axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showing an extra-axial dural-based mass in left parietal region with perilesional edema

Figure 3.

Preoperative axial T1-weighted postcontrast magnetic resonance image showing an intensely enhancing extra-axial mass in the left parietal region

Figure 2.

Preoperative axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance images showing an iso- to hypointense space occupying lesion with perilesional edema in left parietal region

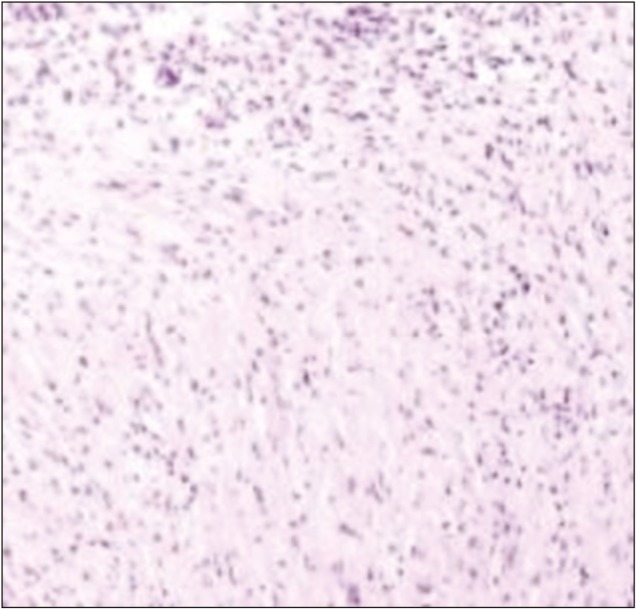

Figure 4.

HPE showing monomorphic spindle cells interspersed in a collagenous background with plasma cell infiltrates (H&E)

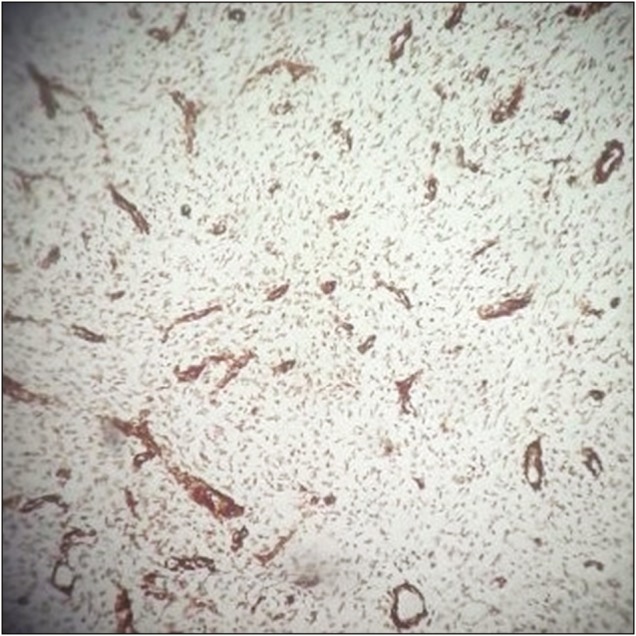

Figure 5.

Spindle cells showing positive alpha-SMA staining

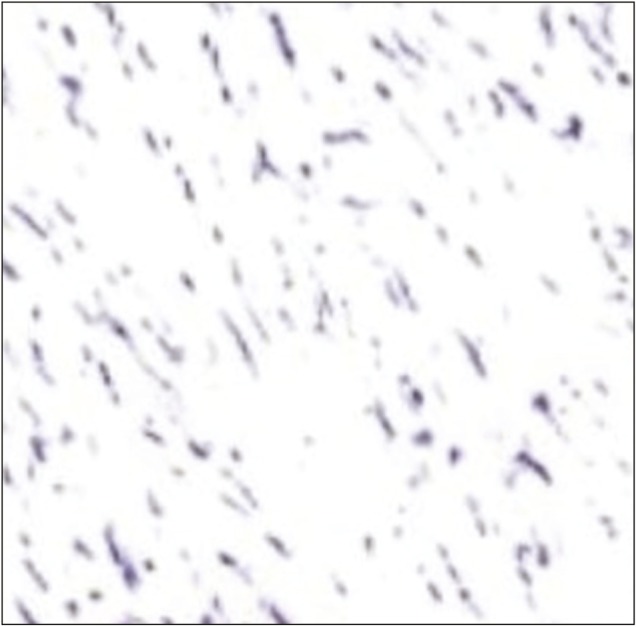

Figure 6.

Spindle cells showing negative staining for EMA

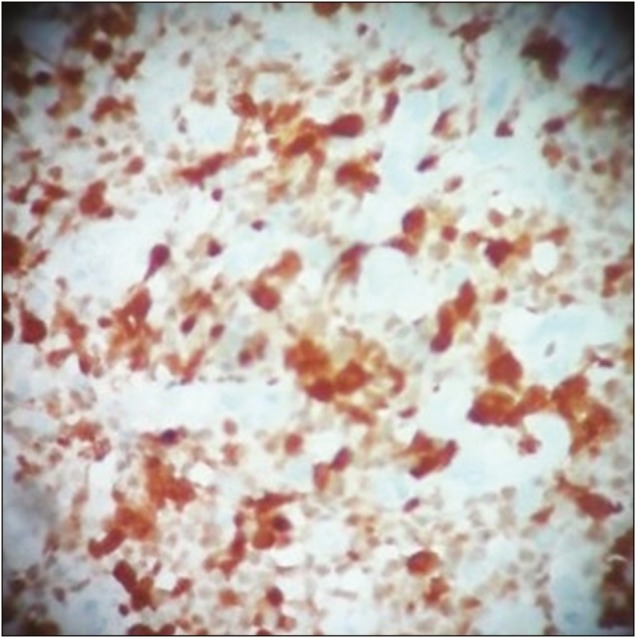

Figure 7.

Spindle cells showing positive staining for ALK

Figure 8.

(A) Preoperative axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showing an extra-axial dural-based mass in left parietal region with perilesional edema. (B) Preoperative axial T2-weighted images showing an iso- to hypointense space occupying lesion. (C) T1-weighted postcontrast image showing an intensely enhancing extra-axial mass. (D) HPE showing monomorphic spindle cells interspersed in a collagenous background with plasma cell infiltrates (H and E). (E and G) Spindle cells showing positive alpha-SMA and ALK staining. (F) Spindle cells showing negative staining for EMA

Intraoperative, lesion was found to be hard in consistency with ill-defined plane of cleavage and firmly adherent to dura. The lesion was excised en bloc. Histopathological examination (HPE) revealed dense inflammatory lesion infiltrating the meninges and reaching up to brain parenchyma. These infiltrates consisted predominantly of mature lymphocytes, plasma cells, blasts of immunoblastic type admixed with histiocytes, and spindle cells. Formation of lymphoid follicles with germinal center and perivascular lymphocytic cuffing was evident along with collagen deposits; however, there was no granuloma formation or necrosis. Spindle cells were positive for alpha smooth muscle actin (SMA) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) but negative for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) in immunohistochemistry. Findings were consistent with diagnosis of meningeal inflammatory tumor.

DISCUSSION

IMTs constitute a heterogeneous group that can exceptionally be found in the central nervous system (CNS).[3] IMT is a distinctive myofibroblastic spindle-cell lesion accompanied by an inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils.[4]

IMT of the CNS is an extremely rare entity such that only 100 cases have so far been reported. Due to rarity of this tumor, exact number of cases in pediatric population is not available but of almost half of the reported cases have been in children and young adults and majority are meningeal.[1,4] They have been labeled with different nomenclature such as inflammatory pseudotumor or plasma cell granuloma.[5]

It is primarily a disease seen in children and young adults but can also occur in old age. Most of these lesions are extra-axial, occurring either as dural-based single lesions or multiple nodular/en plaque lesions.[6]

The etiology of IMT of CNS is unknown, but >60% of IMTs in CNS arise from the dural/meningeal structures and only 12% lesions are intraparenchymal.[4]

IMT of the CNS can be classified into two histopathological types: (a) fibrohistiocytic variant (a form rich in spindle myofibroblasts mixed with few inflammatory cells) and (b) plasma cell granuloma type (composed mainly of plasma cells and lymphocytic infiltration). Recent case series proposed that the two types are different in terms of tumor aggressiveness.[6,7,8]

IMT is difficult to diagnose on imaging features alone, but should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of focal and generalized meningeal thickening. The diagnosis of inflammatory pseudotumor is made at the time of histological evaluation and should be considered after exclusion of infectious, neoplastic, or dysimmune causes.

IMT should be differentiated from tuberculosis, fibroblastic en plaque meningioma, plasmacytoma, and lymphoma.[9,10] Clinical features, serological tests, and CSF examination were not consistent with diagnosis of tuberculosis. Meningioma was excluded because of its rarity in children without history of cranial irradiation, neurofibromatosis type II, or other genetic predisposition. Also most meningiomas do not show restricted diffusion, except atypical lesions.

The immunohistochemical polyclonality of plasma cells helps in exclusion of the diagnosis of plasmacytoma as well as lymphoma.[6,11] Moreover, lymphoma is usually seen in middle-aged women with slow progression of symptoms such as headache, seizures, and meningeal signs and imaging usually suggestive of distinct brain–tumor interface.

CONCLUSION

This case report emphasizes the need to consider the possibility of IMT in the differential diagnosis of dural-based tumors of children and early adulthood. Localized or diffuse dural thickening with T2 low signal intensity, T1 iso-signal intensity, and diffuse contrast enhancement combined with single or multiple enhancing dural-based masses surrounded by brain parenchymal edema is a common MRI finding of meningeal intracranial IMT and helpful in clinching the diagnosis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Swami Muktinathananda, Secretary, Vivekananda Polyclinic and Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India, for guiding and permitting them to publish this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fletcher CDM, Unni K, Mertens F. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002. Pathology and Genetics, Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone World Health Organization Classification of Tumours; pp. 91–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahadori M, Liebow AA. Plasma cell granulomas of the lung. Cancer. 1973;31:191–208. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197301)31:1<191::aid-cncr2820310127>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook JR, Dehner LP, Collins MH, Ma Z, Morris SW, Coffin CM, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) expression in the inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a comparative immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1364–71. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Häusler M, Schaade L, Ramaekers VT, Doenges M, Heimann G, Sellhaus B. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the central nervous system: report of 3 cases and a literature review. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:253–62. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeon YK, Chang KH, Suh YL, Jung HW, Park SH. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the central nervous system: clinicopathologic analysis of 10 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:254–9. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lui PC, Fan YS, Wong SS, Chan AN, Wong G, Chau TK, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the central nervous system. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1611–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swain RS, Tihan T, Horvai AE, Di Vizio D, Loda M, Burger PC, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the central nervous system and its relationship to inflammatory pseudotumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:410–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elster AD, Challa VR, Gilbert TH, Richardson DN, Contento JC. Meningiomas: MR and histopathologic features. Radiology. 1989;170:857–62. doi: 10.1148/radiology.170.3.2916043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee YC, Chueng YC, Hsu SW, Lui CC. Idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis: case report with 7 years of imaging follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:119–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buccoliero AM, Caldarella A, Santucci M, Ammannati F, Mennonna P, Taddei A, et al. Plasma cell granuloma—an enigmatic lesion: description of an extensive intracranial case and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:e220–3. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-e220-PCGEL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor).A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:859–72. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]