Graphical abstract

Keywords: Ceratonia siliqua L., Carob pods, Carob seeds, Cultivars, FTIR, Chemometrics

Abstract

Carob samples from seven different Mediterranean countries (Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Spain, Turkey, Jordan and Palestine) were analyzed using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Seed and flesh samples of indigenous and foreign cultivars, both authentic and commercial, were examined. The spectra were recorded in transmittance mode from KBr pellets. The data were compressed and further processed statistically using multivariate chemometric techniques, including Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Cluster Analysis (CA), Partial Least Squares (PLS) and Orthogonal Partial Least Square-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA). Specifically, unsupervised PCA framed the importance of the variety of carobs, while supervised analysis highlighted the contribution of the geographical origin. Best classification models were achieved with PLS regression on first derivative spectra, giving an overall correct classification. Thus, the applied methodology enabled the differentiation of carobs flesh and seed per their origin. Our results appear to suggest that this method is a rapid and powerful tool for the successful discrimination of carobs origin and type.

Introduction

Carob tree (Ceratonia siliqua L.) has been widely grown in Mediterranean region for centuries and is also widespread in almost all continents (Europe, Africa, Australia, Asia, USA) [1]. Furthermore, is an important component of the Mediterranean vegetation and a characteristic part of the agricultural ecosystem in Cyprus. However, its economic, social and environmental importance may not been fully appreciated. According to the Food Agriculture Organization (FAO), the countries with the highest carob production in 2014 were Spain, Italy, Portugal, Morocco, Turkey, Greece, Cyprus and Lebanon [2]. The quality and quantity of carobs is affected by a number of parameters, such as the local micro-climate, water quality, soil content, altitude and sunshine. The majority of the studies thus far on carob cultivars have focused mainly on the local varieties e.g. in Morocco [3], Turkey [4], [5], [6], Spain [7] and in South Africa [8], overlooking its wide worldwide prevalence. The cultivars are characterized based on their genetic variability, fruit description, chemical composition and agronomical performance [9]. In Spain alone, there have been more than 20 cultivars varieties reported growing in different areas [1].

The main components of carob tree are the pods and the seeds. The latter (about 10% of the fruit), are industrially used to produce locust bean gum (LBG, E410), which can be utilized as a thickener and food stabilizer or in flavoring [10]. Indeed, this is the most valued part for the food industry; its market and food exploitation are still under investigation. The evaluation of the rheological properties and sugar content of LBG from Italian carob varieties was examined [11], whereas other researchers compared the structural and rheological properties of locust bean galactomannans isolated from carob seeds [12]. In the latter study, 12 carob trees from different varieties and growth locations of Southern Greece were examined. The chemical composition of carobs is well known: carob pods contain high amounts of carbohydrates, polyphenolic and antioxidant compounds, insoluble dietary fibers and minerals and low amounts of proteins and lipids [10]. Khlifa et al., studied the chemical composition of carob pods from Morocco, as well as their morphological properties [13]. The elemental profiling of carob fruits (wild and grafted) has also been studied. The most abundant minerals in carob fruit are calcium, potassium, magnesium, sodium, phosphorus and iron [14]. Youseff et al., also examined the gross chemical composition, minerals, vitamins, phenolic compounds and fatty acid content of carob powder [15]. Carob flour is another important food ingredient produced from the carob seeds. Ayaz et al., studied the nutrient composition of commercially- and home-prepared carob flour [16], whereas Durrazzo et al., examined the antioxidant properties of commercially available carob seed flours [17]. The effect of carob and germ flour addition in gluten-free bakery products has been also reported [18], [19], [20], whereas the alternative uses of carob fruit are still examined. Carob seed residues were proposed as substrate or soil organic amendment [21], and the carob pods were recommended for the production of bioethanol after fermentation [22].

The biological and thearapeutic effects of carob fruit e.g. gastrointestinal effects, anti-diabetic activity, anti-cancer, hyperlipidemia and anti-diarrheal properties were recently reviewed. D-pinitol is considered an important bioactive compound of carobs with anti-diabetic activity [23]. It was identified along with sugar profile in carob syrup, a traditional product produced from carob pods [5]. The antibacterial activity of carob leaves extracts against Listeria monocytogenes and Pectobacterium atrosepticum has also been reported [24], [25]. Furthermore, the anticancer, cytotoxic and anti-diarrheal activities of carob fiber, germ flour extracts (seed) and carob pod attributed to the presence of polyphenols, flavonoids and tannins were reported in detail [23]. The presence of polyphenols in carob pods and in derived products was determined using high performance liquid chromatography-ultraviolet absorption-electrospray ion trap-mass spectrometry (HPLC-UV-ESI-MS) and in carob flour using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) [26], [27]. The leaf flavonoid composition was also determined [28].

Nowadays, carob pods is used primarily as food for the livestock [29]. For humans, it is mostly used as a cocoa substitute due to its low price and as a caffeine free product. The carob pods are widely employed in bakery and confectionery products, pasta or beverages. Furthermore, they are used in biotechnology applications for the production of citric and lactic acid, mannitol, succinic acid and ethanol [10], [23].

The carob tree has long been associated with the ancient history of Cyprus; the first written reports of carobs existence in the island were associated with the Venetians in the 15th century [30]. In Cyprus, the carob tree is widely known as “teratsia”. In the old days, it was described as the “black gold of Cyprus”, since it was the product with the largest agricultural exports and an important source of income. According to the macroscopic observations of carob pods, three cultivars exist in Cyprus: Tylliria, Koumpota and Kountourka. A number of traditional carob products are therefore produced, such as carob syrup (charoupomelo), carob powder and pastelli.

In recent years, there has been a great interest in the identification of botanical or geographical origin of foods. Indeed, the European countries are working towards highlighting the geographic origin, protected designation of origin (PDO) and protected geographical indication (PGI) of the traditional food products following European Union regulation No 1151/2012 [31]. To this effect, many analytical methods are employed including mass spectrometric, spectroscopic, separation and other (sensory and DNA) techniques [32]. Of these, FTIR spectroscopy is considered a simple (requiring minimum sample preparation), rapid, low-cost and non-destructive applied spectroscopic method.

The powerful combination of FTIR and chemometrics has been successfully applied in many research areas in food and beverages. A wide array of chemometric methods are therefore used including Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA), Canonical Variate Analysis (CVA), Discriminant Analysis (DA), Soft Independent Modelling by Class Analogy (SIMCA), Artificial Neural Network (ANN) and Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS). Indeed, the previous combined methodologies were applied for the detection of foodborne pathogenic bacteria [33]. The mid-infrared (MIR) spectroscopy (400–4000 cm−1) associated with chemometric methods was used to discriminate wines, cheeses, olive oils and honey according to their geographical origin [32]. The same methodology was also used for the quantitative analysis of food ingredients such as sugars or organic acids in fruits, fruit juices and soft drinks, aiming in product authenticity or adulteration [34]. Moreover, near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy (4000–14,000 cm−1) coupled with chemometric techniques were employed for the geographical classification of grapes, wines, rice, soy sauce and olive oils [32]. The authenticity of local wines in Cyprus was also studied by spectroscopic and chemometric analysis [35]. In general, the combination of attenuated total reflectance (ATR) with FTIR enhances sample spectral collection [36]. Similar applications highlighting the successful combination of FTIR and chemometric techniques in food and beverages are shown in Supplementary Material Table SM-1 [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44].

To our knowledge, only Alabdi et al., used FTIR and chemometric techniques (HCA, PCA and PLS-DA) to discriminate and classify samples of pods and seeds from Moroccan regions [3]. The latter method was applied for the differentiation of LBG among other carbohydrate gums and gums mixtures [45]. Furthermore, Farag et al., studied the aroma profile of roasted and unroasted carob pods using solid-phase microextraction gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (SPME-GC-MS) analysis associated with chemometrics [46]. Also, capillary zone electrophoresis was combined with chemometrics for the classification of carob gum samples [47]. Given the increasing commercial value of carobs, it is necessary to distinguish Cypriot authentic carobs from carobs produce in other countries. As a part of a wider study, our aim was to examine the application of FTIR and chemometrics as a rapid methodology in order to differentiate the origin of carobs, as well the type of 16 carob cultivars from 7 Mediterranean countries (Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Spain, Turkey, Jordan and Palestine), both authentic and commercial. It is believed that the basis for the differentiation of carobs is related to the geological and climatic conditions existing in the production area.

Experimental

Carob pods (flesh and seed) from Cyprus and six other Mediterranean countries (Greece, Italy, Spain, Turkey, Jordan and Palestine) were studied (Table 1). Carob samples from Cyprus, Greece, Italy and Spain were authentic (from cultivars), while samples from Turkey, Jordan and Palestine were commercial from local markets. The seed was grounded in the laboratory mill 3100, while the flesh was grounded in blender Cuisine 4200 magimix. Prior to spectroscopic analysis, samples were placed in an oven at 130 °C for 1½ h and the moisture content was measured (for the seeds it was ranged between 7.6 and 11.4 %, while for the flesh it was 9.1–16.5%). The FTIR analysis was performed randomly (in terms of the sample number and country of origin) both in the flesh and the seed. The transmittance spectra were obtained under controlled environmental conditions on a Jasco FT/IR-6100 spectrophotometer in two different ways: (a) as pressed KBr pellet and (b) with small sample placement on ATR on a ZnSe [3], [37]. The spectra recorded in duplicate in the wavelength region of 400–4000 cm−1 with 128 scans and a 16 cm−1 resolution. A background was collected before each sample was analyzed and then subtracted automatically from the sample spectra prior to further analysis. The first- and second- derivatives were applied to the recorded transmittance spectra. However, the ATR-FTIR experimental approach presented unsatisfied discriminant analysis for the recorded spectra. Finally, the spectra recorded by the use of KBr pellets provide better discrimination and therefore were studied first, for the whole wavelength range of 400–4000 cm−1 and then for specific ranges (400–1500 cm−1, 1500–2500 cm−1 and 2500–4000 cm−1). The multivariate statistical analysis of spectroscopic data was performed with SIMCA software (version 13.0, Umetrics, Sweden). PCA and CA chemometric techniques were used for the classification of samples and PLS and OPLS-DA for their discrimination.

Table 1.

Examined carob cultivars per country.

| Country | Cultivars | * Sample type |

|---|---|---|

| Cyprus | 3 (Tylliria, Koumpota, Kountourka) | Flesh and seed |

| Greece | 3 (Imera, Imera,aUnknown) | Flesh and seed |

| Italy | 4 (Raexmosa, Giubiliana, Saccarata, Unknown) | Flesh and seed |

| Spain | 3 (Negra, Rojal, Metalafera) | Flesh and seed |

| Turkey | 1 (Fleshy) | Flesh and seed |

| Jordan | 1 (Unknown) | Flesh and seed |

| Palestine | 1 (Unknown) | Flesh and seed |

Samples originated from European countries were collected from field cultivars, whereas samples from Middle East countries from local stores (post-harvest samples).

Freshly watered.

Results and discussion

In the infrared region, molecules vibrations correspond to specific vibration frequencies revealing functional group vibrations directly correlated with molecular identification [48], [49], [50], [51]. A full assignment of the spectral bands in carobs is very challenging, but this was not the scope of the present study. The baseline-corrected and area normalized spectra were transformed to absorbance units and truncated to 250 points. Fig. 1 presents representative FTIR absorption spectra of carob flesh and seed sample from Cyprus (Kountourka cultivar) in the 400–4000 cm−1 region. The main bands are shown in Fig. 1 and the analysis of the characteristic peaks of the spectra is given in Table 2. In all the obtained IR spectra, peaks corresponding to the main atmospheric components (CO2, H2O) were observed. The peak at 3600 cm−1 is attributed to H2O, whereas, the double peak near 2300 cm−1 corresponds to CO2. The bands at 3386, 3390 and 3336 cm−1 arise from the O—H and N—H stretching vibrations from polysaccharides and proteins, while the bands at 2927 and 2935 cm−1 correspond to CH2 asymmetric or symmetric stretch. The bands at 1628–1650 and 1543 cm−1 result from stretching or bending vibrations of the bonds which may be derived from proteins. Absorption bands at 1435, 1404 and 1346 cm−1 correspond to CH2 bending vibrations, rocking vibrations of C—H bonds and bending vibrations of CH3 groups, respectively [49], [50], [51]. The most important area in the spectrum for distinguishing the origin of the samples was the region 2500–4000 cm−1, that contains mainly the bands of proteins, polysaccharides, unsaturated lipids and carbohydrates. Fig. SM-1 shows all the obtained spectra of carob flesh samples from the 16 carob cultivars (whereas Fig. SM-2 shows only the spectra of Cypriot carob seed samples Koumpota, Kountourka, Tylliria cultivars in the 400–4000 cm−1 region). The differences between them are small and therefore their distinction in the different regions of the spectra is limited. The profiles of the first and second derivatives of the transmittances are shown in Fig. 2. As mentioned above for the primary spectra, most of the spectral information used to discriminate the samples lies in the region 2500–4000 cm−1. The first derivative is more informative, so chemometric analysis was then performed to these data.

Fig. 1.

FTIR spectra of carob flesh and seed sample from Cyprus (Kountourka) in the 400–4000 cm−1 region (offset for clarity).

Table 2.

Main bands of carob flesh and seed sample with the corresponding functional group vibrations.

| Frequency (cm−1) | Functional group vibration | Possible origin | Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3336–3386 | O—H and N—H group stretching vibration | Polysaccharides, protein | [49] |

| 2927–2935 | CH2 asymmetric or symmetric stretch | Mainly unsaturated lipid and little contribution from proteins, carbohydrates, nucleic acids | [49], [50], [51] |

| 1628–1650 | C O stretch (1652 cm−1) | Protein | [49], [50] |

| cis C C (1654 cm−1) | |||

| 1543 | N—H bend, C—N stretch | Protein | [49] |

| 1435 | CH2 bending vibrations (1462 cm−1) | Lipids, proteins | [49], [50], [51] |

| Rocking vibrations of CH bonds (1417 cm−1) | cis-disubstituted alkenes | ||

| 1404 | Rocking vibrations of CH bonds | cis-disubstituted alkenes | [50], [51] |

| 1346 | CH3 bending vibrations | Lipids, proteins | [49], [50] |

| 1238–1245 and 1122 | Stretching vibration of C—O group (1228 and 1155 cm−1) | Esters | [50] |

| —CH bending and —CH deformation vibrations (1111 and 1097 cm−1) | Fatty acids | ||

| 1065–1068 | C—O stretching | – | [50], [51] |

| 400–1000 | “Fingerprint region” | – | [33] |

Fig. 2.

1st (A) and 2nd (B) spectra derivatives of carob flesh samples from different origin.

Chemometric analysis

The matrix of the FTIR spectral data set was imported into the SIMCA-P version 13.0 (Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden) for statistical analysis. The data were mean-centered with UV scaling, log transformation and the PCA and PLS-DA models were extracted at a confidence level of 95%. The quality of the model was described by the goodness-of-fit R2 (0 ≤ R2 ≤ 1) and the predictive ability Q2 (0 ≤ Q2 ≤ 1) values. First, the exploratory PCA was applied to estimate the systematic variation in a data matrix by a low-dimensional model plane, which allowed a better visualization of the data. The scores produced were then used to classify the samples into one of the 7 groups, according to their geographical origin. The new variables (set of axes) are combinations of the absorbances at each wavenumber.

Table SM-2 reports the cumulative percentage of the total variance provided by the first 10 principal components (PCs) obtained from the whole data set, through the NIPALS (non-linear iterative partial least squares) algorithm. With regard to the overall PCA, it can be noted that the 96.4% of the total variance is explained by the first 5 components (Fig. SM-3). The PCA scatter plot (PC1 vs. PC2) of FTIR spectra (KBr, transmission) in the whole area (400–4000 cm−1) (Fig. SM-4), shows an overlap between groups with respect to their geographical origin. This was improved when the analysis was obtained on the spectra in a smaller wavelength region.

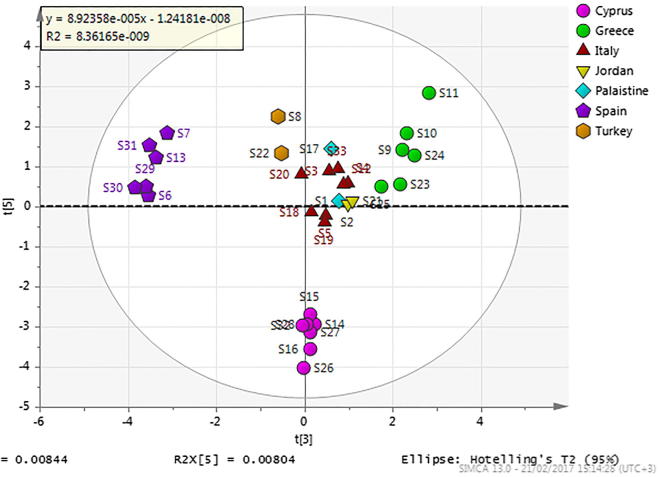

Fig. 3 shows the PCA results (PC3 vs. PC5 score plot) in the wavelength range of 2500–4000 cm−1. In this case, there was clear differentiation between the carob samples depending on the country of origin. Four separate groups can be identified: (a) carobs from Cyprus (the group was very well formed), (b) carobs from Spain, (c) carobs from Greece and (d) carobs from Italy, Jordan and Palestine. Some small degree of separation between the samples in the last group was suggested in the hyperplane. The samples from Turkey were slightly distinguished from the last group.

Fig. 3.

PCA scatter plot of FTIR spectra (2500–4000 cm−1).

The same procedure applied to the 1st derivatives of the spectra and Fig. 4 shows the PCA results (PC2 vs. PC6 score plot) of the data obtained from the application of the first derivative to the recorded spectra in the wavelength range 2500–4000 cm−1, showing the differentiation according to their type. The separation based on the type of the samples is readily apparent from the plot showing the two groups: (a) samples of carob flesh and (b) samples of carob seed. The above discriminant components were chosen as they best differentiated the carob samples with respect to their origin (Fig. 3) and their type (Fig. 4). Of course PC1 and PC2 explain the maximum variation, probably due to the homogeneity of the carobs throughout its various parts. However, the eigenvalue for each of the 6 PCs in the model range from 1.95 to 2.52, indicates that the model fits well with the data, indicating that they are all important and can be used to classify the samples. To validate the previous results on the influence of the origin, discriminant analysis was applied, by using the “leave-one-out cross-validation” method. The PCA scores of the 1st derivatives of the spectra in the above limited range were then analyzed statistically with PLS and OPLS-DA. OPLS-DA is an extension of the supervised PLS regression method that manages to increase the quality of the classification model by separating the systematic variation in X into two parts, one that is linearly related to Y (predictive information) and one that is unrelated to Y (orthogonal information). The OPLS-DA models at a confidence level of 95% were scaled and log transformed. Fig. 5 (three-dimensional) shows the discrimination of samples of different geographical origin into a clear presentation in the plane.

Fig. 4.

PCA scatter plot of 1st spectra derivatives (2500–4000 cm−1).

Fig. 5.

PLS plot from analysis on PCAs of 1st derivatives (2500–4000 cm−1).

Equally, Table 3 summaries the correct classification rates for all samples (PCs of 1st derivatives in 2500–4000 cm−1) after a PLS discriminant analysis (leave-one-out cross-validation) and points out the potential of this technique to discriminate the groups with 100% correct classification without error (Figs. SM-5 and SM-6 report the OPLS-DA scatter plot on PCAs and the dendrogram by HCA in the same wavelength range, respectively).

Table 3.

Correct classification rates for all samples (PCs of 1st derivatives in 2500–4000 cm−1) after PLS-DA.

| True classa | Total number | Correct | Assigned classes |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 1 | 7 | 100% | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 6 | 100% | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 8 | 100% | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 2 | 100% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 2 | 100% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 6 | 100% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 5 | 2 | 100% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| No class | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 33 | 100% | 7 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| Fishers prob. 1.2e−021 | |||||||||

1: Cyprus, 2: Greece, 3: Italy, 4: Jordan, 5: Palestine, 6: Spain, 7: Turkey.

Conclusions

In summary, in our study which is part of a wider investigation on carobs, we examined whether a combination of FTIR spectroscopy and subsequent chemometric data analysis could be applied in order to differentiate carob samples from different geographical regions. Our results have clearly demonstrated that the carob samples could be categorized into distinct groups depending on their origin and type, as well the chemometric technique that was used for the analysis of the spectroscopic data. The use of appropriate algorithm on the PCs of the first derivatives of the spectra in the wavelength range 2500–4000 cm−1, gives groups of samples with confidence level 95%. The discriminant analysis with the leave-one-out cross-validation, correctly classified the samples, rising to 100% for each group.

The uncertainty of the method is of great importance for the development of the models that may differentiate carobs of different origin. Therefore, to build such models, much larger sample sets comprising carobs from many years and harvests from different countries would be needed. Thus, the method could prove to be a useful tool for discriminating carobs from different origin and type.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the “Black Gold” project, financially supported by the University of Cyprus.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2017.12.001.

Contributor Information

Agapios Agapiou, Email: agapiou.agapios@ucy.ac.cy.

Rebecca Kokkinofta, Email: sglsnif@cytanet.com.cy.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

References

- 1.Batlle I., Tous J. vol. 17. Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, Gatersleben/International Plant Genetic Resources Institute; Rome: 1997. (Carob tree. Ceratonia siliqua L. Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available from: <http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC> [accessed September 12, 2017].

- 3.Alabdi F. Carob origin classification by FTIR spectroscopy and chemometrics. J Chem Chem Eng. 2011;5:1020–1029. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biner B., Gubbuk H., Karhan M., Aksu M., Pekmezci M. Sugar profiles of the pods of cultivated and wild types of carob bean (Ceratonia siliqua L.) in Turkey. Food Chem. 2007;100:1453–1455. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tetik N., Turhan I., Oziyci H.R., Karhan M. Determination of d-pinitol in carob syrup. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2011;62:572–576. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2011.560564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turhan I. Relationship between sugar profile and D-Pinitol content of pods of wild and cultivated types of Carob Bean (Ceratonia siliqua L.) Int J Food Prop. 2014;17:363–370. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dakia P.A., Wathelet B., Paquot M. Isolation and chemical evaluation of carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) seed germ. Food Chem. 2007;102:1368–1374. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sigge G.O., lipumbu L., Britz T.J. Proximate composition of carob cultivars growing in South Africa. South African J Plant Soil. 2011;28:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tous J., Romero A., Hermoso J.F., Ninot A., Plana J., Batlle I. Agronomic and commercial performance of four Spanish Carob Cultivars. Hort Technol. 2009;19:465–470. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rababah T.M., Al-u’datt M., Ereifej K., Almajwal A., Al-Mahasneh M., Brewer S., et al. Chemical, functional and sensory properties of carob juice. J Food Qual. 2013;36:238–244. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizzo V., Tomaselli F., Gentile A., La Malfa S., Maccarone E. Rheological properties and sugar composition of locust bean gum from different carob varieties (Ceratonia siliqua L.) J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:7925–7930. doi: 10.1021/jf0494332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazaridou A., Biliaderis C.G., Izydorczyk M.S. Structural characteristics and rheological properties of locust bean galactomannans: a comparison of samples from different carob tree populations. J Sci Food Agric. 2001;81:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khlifa M., Bahloul A., Kitane S. Determination of chemical composition of carob pod (Ceratonia siliqua L) and its morphological study. J Mater Environ Sci. 2013;4:348–353. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oziyci H.R., Tetik N., Turhan I., Yatmaz E., Ucgun K., Akgul H., et al. Mineral composition of pods and seeds of wild and grafted carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) fruits. Sci Hortic (Amsterdam) 2014;167:149–152. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youssef M.K.E., El-Manfaloty M.M., Ali H.M. Assessment of proximate chemical composition, nutritional status, fatty acid composition and phenolic compounds of carob (Ceratonia Siliqua L.) Food Public Heal. 2013;3:304–308. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayaz F.A., Torun H., Glew R.H., Bak Z.D., Chuang L.T., Presley J.M., et al. Nutrient content of carob pod (Ceratonia siliqua L.) flour prepared commercially and domestically. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2009;64:286. doi: 10.1007/s11130-009-0130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durazzo A., Turfani V., Narducci V., Azzini E., Maiani G., Carcea M. Nutritional characterisation and bioactive components of commercial carobs flours. Food Chem. 2014;153:109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsatsaragkou K., Gounaropoulos G., Mandala I. Development of gluten free bread containing carob flour and resistant starch. LWT – Food Sci Technol. 2014;58:124–129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsatsaragkou K., Yiannopoulos S., Kontogiorgi A., Poulli E., Krokida M., Mandala I. Mathematical approach of structural and textural properties of gluten free bread enriched with carob flour. J Cereal Sci. 2012;56:603–609. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsatsaragkou K., Yiannopoulos S., Kontogiorgi A., Poulli E., Krokida M., Mandala I. Effect of carob flour addition on the rheological properties of Gluten-Free Breads. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014;7:868–876. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabecinha A., Guerrero C., Beltrao J., Brito J. Carob residues as a substrate and a soil organic amendment. WSEAS Trans Environ Dev. 2010;6:317–326. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazaheri D., Shojaosadati S.A., Mousavi S.M., Hejazi P., Saharkhiz S. Bioethanol production from carob pods by solid-state fermentation with Zymomonas mobilis. Appl Energy. 2012;99:372–378. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goulas V., Stylos E., Chatziathanasiadou M.V., Mavromoustakos T., Tzakos A.G. Functional components of carob fruit: linking the chemical and biological space. Int J O F Mol Sci. 2016;17(11) doi: 10.3390/ijms17111875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aissani N., Coroneo V., Fattouch S., Caboni P. Inhibitory effect of carob (Ceratonia siliqua) leaves methanolic extract on Listeria monocytogenes. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:9954–9958. doi: 10.1021/jf3029623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meziani S., Oomah B.D., Zaidi F., Simon-Levert A., Bertrand C., Zaidi-Yahiaoui R. Antibacterial activity of carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) extracts against phytopathogenic bacteria Pectobacterium atrosepticum. Microb Pathog. 2015;78:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ortega N., Macià A., Romero M.-P., Trullols E., Morello J.-R., Anglès N., et al. Rapid determination of phenolic compounds and alkaloids of carob flour by improved liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:7239–7244. doi: 10.1021/jf901635s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papagiannopoulos M., Wollseifen H.R., Mellenthin A., Haber B., Galensa R. Identification and quantification of polyphenols in carob fruits (Ceratonia siliqua L.) and derived products by HPLC-UV-ESI/MSn. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:3784–3791. doi: 10.1021/jf030660y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaya J., Mahmood S. Flavonoid content in leaf extracts of the fig (Ficus carica L.), carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) and pistachio (Pistacia lentiscus L.) BioFactors. 2006;28:169–175. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520280303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Obeidat B.S., Alrababah M.A., Abdullah A.Y., Alhamad M.N., Gharaibeh M.A., Rababah T.M., et al. Growth performance and carcass characteristics of Awassi lambs fed diets containing carob pods (Ceratonia siliqua L.) Small Rumin Res. 2011;96:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casola P. At the University Press; Manchester: 1907. Canon Pietro Casola’s Pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the year 1494. [Google Scholar]

- 31.REGULATION (EU) No 1151/2012 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 November 2012 on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs. Available from: <http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32012R1151> [accessed September 12, 2017].

- 32.Luykx D.M.A.M., van Ruth S.M. An overview of analytical methods for determining the geographical origin of food products. Food Chem. 2008;107:897–911. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis R., Mauer L.J. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy: a rapid tool for detection and analysis of foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Curr Res Technol Educ Top Appl Microbiol Microb Biotechnol. 2010;2(2):1582–1594. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bureau S., Ruiz D., Reich M., Gouble B., Bertrand D., Audergon J.-M., et al. Application of ATR-FTIR for a rapid and simultaneous determination of sugars and organic acids in apricot fruit. Food Chem. 2009;115:1133–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ioannou-Papayianni E., Kokkinofta R.I., Theocharis C.R. Authenticity of Cypriot Sweet Wine Commandaria using FT-IR and chemometrics. J Food Sci. 2011;76:C420–C427. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cozzolino D. Recent trends on the use of infrared spectroscopy to trace and authenticate Natural and Agricultural Food Products. Appl Spectrosc Rev. 2012;47:518–530. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craig A.P., Franca A.S., Oliveira L.S. Evaluation of the potential of FTIR and chemometrics for separation between defective and non-defective coffees. Food Chem. 2012;132:1368–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tarantilis P.A., Troianou V.E., Pappas C.S., Kotseridis Y.S., Polissiou M.G. Differentiation of Greek red wines on the basis of grape variety using attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2008;111:192–196. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly J.F.D., Downey G. Detection of sugar adulterants in apple juice using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:3281–3286. doi: 10.1021/jf048000w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva S.D., Feliciano R.P., Boas L.V., Bronze M.R. Application of FTIR-ATR to Moscatel dessert wines for prediction of total phenolic and flavonoid contents and antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. 2014;150:489–493. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva S.D., Rosa N.F., Ferreira A.E., Boas L.V., Bronze M.R. Rapid determination of α-tocopherol in vegetable oils by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Food Anal Methods. 2008;2:120. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Etzold E., Lichtenberg-Kraag B. Determination of the botanical origin of honey by Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy: an approach for routine analysis. Eur Food Res Technol. 2008;227:579–586. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banc R., Loghin F., Miere D., Fetea F., Socaciu C. Romanian wines quality and authenticity using FT-MIR spectroscopy coupled with multivariate data analysis. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2014;42(2):556–564. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anjos O., Santos A.J.A., Estevinho L.M., Caldeira I. FTIR–ATR spectroscopy applied to quality control of grape-derived spirits. Food Chem. 2016;205:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.02.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prado B.M., Kim S., Özen B.F., Mauer L.J. Differentiation of carbohydrate gums and mixtures using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:2823–2829. doi: 10.1021/jf0485537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farag M.A., El-Kersh D.M. Volatiles profiling in Ceratonia siliqua (Carob bean) from Egypt and in response to roasting as analyzed via solid-phase microextraction coupled to chemometrics. J Adv Res. 2017;8:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanrahan G., Gomez F.A. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2009. Chemometric methods in capillary electrophoresis. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mellado-Mojica E., Seeram N.P., López M.G. Comparative analysis of maple syrups and natural sweeteners: Carbohydrates composition and classification (differentiation) by HPAEC-PAD and FTIR spectroscopy-chemometrics. J Food Compos Anal. 2016;52:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dogan A., Siyakus G., Severcan F. FTIR spectroscopic characterization of irradiated hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) Food Chem. 2007;100:1106–1114. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rohman A., Sismindari, Erwanto Y., Che Man Y.B. Analysis of pork adulteration in beef meatball using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Meat Sci. 2011;88:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rohman A., Man Y.B.C. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy for analysis of extra virgin olive oil adulterated with palm oil. Food Res Int. 2010;43:886–892. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.