Abstracts

Background

Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) plays an important role in cholesterol esterification in serum. Serum LCAT activity is elevated in patients with serum high triglyceride and low high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations, both of which are related to metabolic syndrome and subsequent diabetes mellitus, referred to as lipotoxicity. We hypothesized that increased serum LCAT activity could predict future risk of diabetes mellitus in a general Japanese population.

Methods

We prospectively studied 1496 individuals aged 20–86 years without histories of diabetes mellitus at baseline. Serum lipid concentrations, glucose parameters, and LCAT activity measured as the serum cholesterol esterification rate, were evaluated.

Results

During 11 years of follow-up, 46 newly diagnosed patients with diabetes mellitus were reported. After adjustment for plasma glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, the relative risks (RRs) for the development of diabetes mellitus were 5.45 [95% confidence interval (95% CI) 2.37–12.55; P < 0.001] for body-mass index, 0.22 (95% CI, 0.09–0.53; P = 0.001) for HDL-C, 4.81 (95% CI, 1.96–11.77; P = 0.001) for triglyceride, and 4.64 (95% CI, 1.89–11.41; P = 0.001) for LCAT activity. After adjustment for HbA1c, total cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-C, phospholipid, and free fatty acid levels, the RR of LCAT activity for future risk of diabetes mellitus remained significant (RR, 4.93; 95% CI,1.32–18.41; P = 0.018). In this analysis, we found a significant association between LCAT activity and risk of diabetes mellitus in men but not in women.

Conclusion

Increased serum cholesterol esterification rate is a potent predictor for future diabetes mellitus.

Keywords: Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase, Diabetes, Cholesterol metabolism, Epidemiology, Insulin resistance, Lipotoxicity, Cohort study

Background

Dyslipidemic conditions, represented by serum high TG, low high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), and increased free fatty acid concentrations, are associated with insulin resistance and subsequent diabetes mellitus [1–4]. The accumulation of lipids and lipid metabolites, such as fatty acyl-CoA, diacylglycerol, and ceramide, in circulating blood and non-adipose tissues deteriorates insulin signaling and promotes beta-cell apoptosis, referred to as lipotoxicity [5–8]. Nevertheless, the detailed mechanisms by which lipids cause diabetes mellitus in general populations have not yet been fully elucidated. Lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) is an enzyme that catalyzes the sn-2 position of phosphatidylcholine and the 3-beta-hydroxyl group of cholesterol to form cholesterol ester and lysophosphatidylcholine [9]. This reaction occurs in high-density lipoproteins (HDL) and is therefore thought to be important in HDL maturation and subsequent reverse cholesterol transport to the liver [9, 10]. However, we have previously reported that increased serum LCAT activity measured as serum cholesterol esterification rates were associated with future risk of coronary heart disease and sudden death in a general population [11]. In that study, we also observed that serum LCAT activity was highly correlated with increased waist circumference, increased serum TG concentration, and decreased serum HDL-C concentration, all of which are components of metabolic syndrome and are related to insulin resistance [12]. A number of previous studies also reported similar results [13–16]. These findings may indicate that increased LCAT activity is closely related to increased risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus as well as coronary heart disease, suggesting that both diseases have common antecedents [2, 7, 12]. Furthermore, Recently, Ng et al. have reported a significant decrease in fasting insulin and glucose levels in LCAT- and low-density lipoprotein receptor-knockout mice, despite high serum TG concentration [17, 18]. This result suggests that LCAT may be closely related to insulin resistance and subsequent diabetes mellitus. Taken together, we hypothesized that increased serum LCAT activity is predictive of future risk of diabetes mellitus. Here, we examined the relationship between baseline LCAT activity, measured as serum cholesterol esterification rate, and future risk of diabetes mellitus in a general Japanese population.

Methods

Study population

The Hidaka Cohort Study is a population-based cohort study in the town of Hidaka, a typical Japanese rural community [11, 19]. The baseline survey was conducted in 1993. There were 2155 total participants aged 20–93 years at baseline.

Follow-up and outcomes

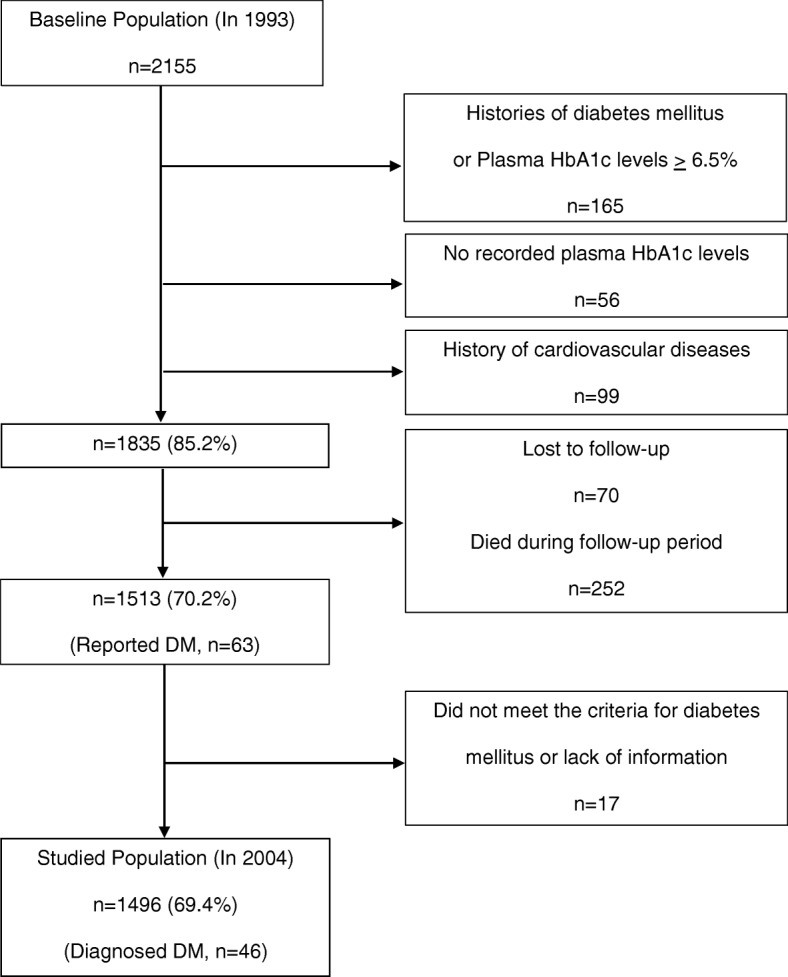

We initiated a follow-up study in 2004. We used mailed questionnaires or telephone interviews to measure the incidence of death, stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer, and newly developed diabetes mellitus during the follow-up period. Among them, 165 participants had histories of diabetes mellitus or whose plasma glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were ≥ 6.5% at baseline. In addition, 56 participants did not have recorded plasma HbA1c levels, and 99 participants had histories of cardiovascular diseases. Of the participants, 70 were lost to follow-up, and 252 died during the follow-up period; these participants were excluded from the analysis. Among the remaining 1513 participants, 63 participants reported newly developed diabetes mellitus during the follow-up period. For these 63 participants, we further confirmed the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus using medical records. The criteria were as follows; plasma HbA1c level ≥ 6.5%, or fasting plasma glucose concentration ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, or 2-h plasma glucose concentration during a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or casual blood glucose concentration ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or current or past use of antidiabetic agents including insulin, sulfonylureas, biguanides, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, meglitinides, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, and thiazolidinediones. Eleven subjects did not meet the criteria and 6 subjects were not determined as having diabetes mellitus due to lack of information. Therefore, these 17 subjects were excluded from the analysis. The remaining 1496 participants consisting of 929 women and 567 men aged 55.7 ± 14.1 years (mean ± SD, range 20–86 years) were eligible for the study. (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Selection procedure

Laboratory procedures

Most of the blood samples were drawn within eight hours after the participants’ last meal; thus, the samples were mainly obtained in a non-fasted state. Serum LCAT activity was determined as described previously [11]. We used a self-substrate method, where decreases in free cholesterol concentrations were measured enzymatically after incubating sera with synthetic dipalmitoyl lecithin using a commercially available kit (Nescoat LCAT kit-S, Alfresa Pharma, Osaka, Japan) based on the method by Nagasaki and Akanuma [20]. The present method is simple and rapid as compared with the traditional endogenous substrate methods using gas-liquid chromatography. Therefore it is suitable for assaying a large number of samples from the cohort and is easy to employ in clinical laboratories. In brief, 0.5 ml of serum was added to 0.3 ml of 2.5 mg/ml lecithin solution and mixed gently. 0.2 ml of the mixture was transferred into a test tube and stored in a refrigerator as a control (A). The remaining mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. 0.2 ml of the mixture was transferred into another test tube (B). 3.0 ml of color reagent for cholesterol measurement was added to both (A) and (B), and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. The difference in absorbance between (A) and (B) at 600 nm was determined, and the decrease of cholesterol concentration was calculated as an LCAT activity (n moles/ml/hr). 1000 n mole/ml of purified cholesterol was used as a reference for calculating cholesterol esterification rate. Therefore, the present assay is a modification of the endogenous substrate assay. To test whether adding dipalmitoyl lecithin into the assay system affects the result of the analysis, we examined the relationship between the present method and the radio-labeled endogenous substrate method by Stokke and Norum [21]. We confirmed a high correlation between the present method and the traditional endogenous substrate method (R = 0.69, P = 0.0087, n = 13, unpublished data). Furthermore, The LCAT activities measured by the present method are highly correlated with those measured by the endogenous substrate method using gas-liquid chromatography (R = 0.829, P < 0.001, n = 22) [20], with those measured by the exogenous substrate method (R = 0.99, P < 0.001, n = 38) [22], and with the LCAT mass concentrations measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R = 0.864, P < 0.001, n = 45) [23]. Therefore, this method is well-validated and reliable for this study. Serum total cholesterol (TC) and TG concentrations were determined by enzymatic methods. High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations were determined using the phosphotungstic acid magnesium chloride precipitation method. Plasma HbA1c levels were measured using high-performance liquid chromatography. Serum immunoreactive insulin (IRI) levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. We calculated the serum non-HDL-C concentration as the difference between serum TC and HDL-C concentrations.

Blood pressure measurement and lifestyle factor assessment

Community nurses interviewed the participants for information on current and past health conditions, medications, and lifestyle. Blood pressure was measured with a standard mercury sphygmomanometer on the right arm after the participants had been sitting at rest for at least 3 min. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.

Statistical analyses

We first calculated the means ± standard deviations, medians, and proportions of potential diabetic risk factors at baseline for the 1496 participants. Student’s t-test, the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test, and the chi-square test were used to examine differences between two groups. We divided the lipid parameter distributions into quartiles, and the quartile-specific relative risks (RRs) and confidence intervals (CIs) for future risk of diabetes mellitus were estimated by multiple logistic regression adjusted for HbA1c levels, lipid concentrations, and their parameters. All of the P values were two-sided, and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All of the analyses were performed with SPSS 11.01 J software for Windows (SPSS, Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Blood pressure, TG concentration, and LCAT activity were higher in men than in women. TC, HDL-C, and Immunoreactive insulin (IRI) levels were higher in women than in men. We found no significant differences in BMI and blood glucose levels between men and women.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort

| Characteristics | Total | Women | Men | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 1496 | 929 | 567 | |

| Age, years | 55.7 ± 14.1 | 55.9 ± 14.1 | 55.3 ± 13.9 | 0.40 |

| History of hypertension, % | 30.3 | 31.8 | 28.0 | 0.12 |

| Current smoker, % | 20.6 | 1.9 | 51.1 | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.5 ±2.9 | 22.5 ± 3.0 | 22.5 ± 2.8 | 0.85 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 72.2 ± 8.1 | 69.6 ± 7.1 | 76.8 ± 7.7 | < 0.001 |

| Waist/Hip | 0.81± 0.07 | 0.78 ±0.06 | 0.85 ± 0.06 | < 0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 132 ± 21 | 131 ± 21 | 134 ± 20 | 0.002 |

| DBP, mmHg | 77 ± 12 | 76 ± 12 | 79 ± 12 | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 5.2 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 5.52 ± 0.70 | 5.52 ± 0.68 | 5.52 ± 0.74 | 0.93 |

| IRI, U/mL | 2.9 (1.7–5.5) | 3.3 (1.9–5.6) | 2.5 (1.3–4.8) | < 0.001 |

| TC, mmol/L | 5.16 ± 0.93 | 5.31 ± 0.93 | 4.92 ± 0.87 | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.54 ± 0.38 | 1.58 ± 0.37 | 1.47 ± 0.37 | < 0.001 |

| Non-HDL-C, mmol/L | 3.62 ± 0.38 | 3.73 ± 0.99 | 3.45 ± 0.94 | < 0.001 |

| TG, mmol/L | 0.99 (0.71–1.42) | 0.95 (0.68–1.33) | 1.11 (0.78–1.61) | < 0.001 |

| Phospholipids, mg/dL | 220 ± 33 | 223 ± 32 | 214 ± 33 | < 0.001 |

| Free fatty acids, Eq/L | 561 (265–854) | 629 (292–912) | 486 (231–755) | < 0.001 |

| LCAT activity, nmol mL-1 hr-1 | 76.9 ± 21.4 | 75.6 ± 21.2 | 79.0 ± 21.5 | 0.003 |

Values are expressed as means ± standard deviations except IRI, TG, and free fatty acids which are given as the medians and the interquartile ranges in parentheses

*P < 0.05 is considered to indicate statistically significant differences between men and women. The Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was used for the differences of IRI, TG and free fatty acids. The other continuous variables were estimated by Student’s t-test

BMI body mass index, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HbA1c glycosylated hemoglobin A1c, IRI immunoreactive insulin, TC total cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, TG triglyceride, LCAT lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase

During the 11.0 years of follow-up, 46 diabetes mellitus cases (21 women, 25 men) were reported from the 1496 participants.

Baseline characteristics of newly diagnosed diabetes and non-diabetes subjects from the total cohort

Table 2 shows baseline characteristics of newly diagnosed diabetes and non-diabetes subjects from the total cohort. BMI, waist circumference, SBP, HbA1c, glucose, and IRI levels were significantly higher in newly diagnosed diabetes subjects than in non-diabetes subjects. Among lipid markers, non-HDL-C, TG concentrations, and LCAT activity were significantly higher in newly diagnosed diabetes subjects, whereas HDL-C was significantly lower in newly diagnosed diabetes subjects.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of newly diagnosed diabetes and non-diabetes subjects from the total cohort

| Characteristics | Non-diabetes | Diabetes | P Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 1450 | 46 | |

| Age, years | 55.6 ± 14.1 | 56.8 ± 10.9 | 0.599 |

| Male sex (%) | 37.4 | 54.3 | 0.02 |

| History of hypertension, % | 30.1 | 39.1 | 0.19 |

| Current smoker, % | 20.3 | 30.4 | 0.09 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.4 ± 2.8 | 25.3 ± 3.0 | < 0.001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 72.0 ± 7.9 | 79.8 ± 10.2 | < 0.001 |

| Waist/Hip | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 0.86 ± 0.08 | < 0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 132 ± 21 | 141 ± 20 | 0.003 |

| DBP, mmHg | 77 ± 12 | 81 ± 13 | 0.01 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 5.6 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 5.51 ± 0.68 | 6.03 ± 1.07 | < 0.001 |

| IRI, U/mL | 2.9 (1.6–5.4) | 4.5 (2.9–8.7) | 0.002 |

| TC, mmol/L | 5.15 ± 0.91 | 5.47 ± 1.23 | 0.02 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.54 ± 0.38 | 1.31 ± 0.32 | < 0.001 |

| Non-HDL-C, mmol/L | 3.61 ± 0.97 | 4.16 ± 1.28 | < 0.001 |

| TG, mmol/L | 0.98 (0.71–1.40) | 1.61 (1.04–2.13) | < 0.001 |

| Phospholipids, mg/dL | 219 ± 32 | 232 ± 45 | 0.01 |

| Free fatty acids, Eq/L | 563 (265–852) | 498 (246–942) | 0.95 |

| LCAT activity, nmol mL−1 h− 1 | 76.4 ± 21.2 | 92.0 ± 21.2 | < 0.001 |

Values are expressed as means ± standard deviations except IRI, TG, and free fatty acids which are given as the medians and the interquartile ranges in parentheses

* P < 0.05 is considered to indicate statistically significant differences between men and women. The Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was used for the differences of IRI, TG and free fatty acids. The other continuous variables were estimated by Student’s t-test

BMI body mass index, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HbA1c glycosylated hemoglobin A1c, IRI immunoreactive insulin, TC total cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, TG triglyceride, LCAT lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase

Univariate and HbA1c-adjusted analysis of risk factors and incidence of diabetes mellitus

Table 3 lists the quartile-specific relative risks (RRs) for the future risk of diabetes mellitus. Using univariate analysis, we found that the significant risk factors for diabetes mellitus according to the highest versus the lowest quartiles included BMI, waist circumference, waist to hip ratio, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), glucose, IRI, HDL-C, TG, non-HDL-C, and LCAT activity. Therefore, most lipid markers were positively associated with the risk of diabetes mellitus except for HDL-C, which was inversely associated with the risk. Among various metabolic factors, increased body weight, abdominal obesity, increased TG, and decreased HDL-C were more likely to be associated with the risk of diabetes mellitus, whereas systolic and diastolic blood pressures were less likely to be associated with the risk. In this analysis, HbA1c as a glucose metabolism parameter was most associated with the risk of diabetes mellitus. Therefore, we included HbA1c as a covariate to the analysis to exclude the potential effects of hyperglycemia on the development of diabetes mellitus. After adjustment for HbA1c levels, we found significant risk factors for diabetes mellitus including BMI, waist circumference, waist to hip ratio, systolic blood pressure, IRI, HDL-C, TG, and LCAT activity. Among these, BMI, increased TG, decreased HDL-C, and increased LCAT activity were associated with the risk of diabetes mellitus with relatively higher RRs than increased blood pressure in this population.

Table 3.

Univariate and HbA1c-adjusted analysis of risk factors and incidence of diabetes mellitus

| Variables | Univariate | HbA1c adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR* (95%CI) | P value | RR* (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.60 | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 0.09 |

| Man | 1.99 (1.11–3.60) | 0.02 | 1.60 (0.87–2.93) | 0.13 |

| History of Hypertension | 1.50 (0.82–2.73) | 0.19 | 1.39 (0.75–2.58) | 0.33 |

| Current smoker | 1.72 (0.91–3.27) | 0.10 | 1.39 (0.72–2.71) | 0.33 |

| BMI | 8.04 (2.81–23.07) | <0.001 | 7.52 (2.58–21.90) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference | 5.57 (2.12–14.63) | <0.001 | 4.23 (1.58–11.30) | 0.004 |

| Waist/hip | 6.10 (2.09–17.80) | 0.001 | 3.76 (1.26–11.22) | 0.02 |

| SBP | 3.99 (1.47–10.81) | 0.006 | 3.06 (1.11–8.45) | 0.03 |

| DBP | 2.26 (1.06–4.82) | 0.04 | 2.09 (0.96–4.57) | 0.06 |

| HbA1c | 16.70 (3.98–70.14) | <0.001 | ||

| Glucose | 3.34 (1.32–8.47) | 0.01 | 2.11 (0.81–5.50) | 0.13 |

| IRI | 2.19 (0.93–5.13) | 0.07 | 2.58 (1.07–6.23) | 0.04 |

| TC | 1.75 (0.79–3.88) | 0.17 | 1.17 (0.52–2.67) | 0.70 |

| HDL-C | 0.16 (0.05–0.46) | 0.001 | 0.18 (0.06–0.54) | 0.002 |

| TG | 10.50 (3.17–34.76) | <0.001 | 8.11 (2.42–27.22) | 0.001 |

| Non-HDL-C | 3.11 (1.31–7.41) | 0.01 | 2.11 (0.86–5.14) | 0.10 |

| Phospholipids | 3.30 (1.20–9.10) | 0.02 | 2.66 (0.95–7.45) | 0.06 |

| Free fatty acids | 1.00 (0.47–2.13) | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.46–2.20) | 0.98 |

| LCAT activity | 9.42 (2.82–31.39) | <0.001 | 7.37 (2.18-24.89) | 0.001 |

*RR indicates a relative risk for diabetes mellitus in quartile 4 subjects as compared with quartile 1 subjects for continuous variables except for age, which is expressed as a risk per one year increment. RR of Man indicates the risk of diabetes mellitus of men compared with that of women

BMI body mass index, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HbA1c glycosylated hemoglobin A1c, IRI immunoreactive insulin, TC total cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, TG triglyceride, LCAT lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase

Lipid- and HbA1c-adjusted multivariable analysis of the risk of diabetes mellitus according to baseline LCAT activity

To determine whether the predictive value of LCAT activity was independent of the other lipid markers, we conducted multivariable analysis adjusted for these lipid markers in addition to HbA1c levels (Table 4). After adjusting for HbA1c, TC, TG, HDL-C, phospholipids, and free fatty acids, the RR of LCAT activity was 4.93 (95% CI, 1.32–18.41; P = 0.018). Therefore, increased LCAT activity was significantly associated with the risk of diabetes mellitus independent of other lipid markers. However, in the analysis performed on men and women separately, we found a significant association between baseline LCAT activity and the future risk of diabetes mellitus only in men (RR 9.15; 95% CI, 1.02–81.95; P = 0.048 for men and RR, 2.67; 95% CI, 0.47–15.41; P = 0.27 for women). When we performed a multivariable analysis including BMI as a covariate in addition to lipids and HbA1c levels, we could not find any significant associations between LCAT activity and risk of diabetes mellitus in this analysis (data not shown).

Table 4.

Lipid- and HbA1c-adjusted multivariable analysis of the risk of diabetes mellitus according to baseline LCAT activity

| Number of subjects | RR* | 95%CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 929 | 2.67 | 0.47–15.41 | 0.27 |

| Men | 567 | 9.15 | 1.02–81.95 | 0.048 |

| Total | 1496 | 4.93 | 1.32–18.41 | 0.018 |

*RR indicates a relative risk for diabetes mellitus in quartile 4 subjects as compared with quartile 1 subjects of LCAT activities, adjusted for HbA1c, TC, TG, HDL-C, phospholipids, and free fatty acids

LCAT lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase, HbA1c glycosylated hemoglobin A1, TC total cholesterol, TG triglyceride, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Discussion

In this population-based cohort study, most of the variables predicting future diabetes mellitus are also known to be risk factors for coronary heart disease. Among these, serum LCAT activities were significantly associated with future risk of diabetes mellitus. This association was independent of other lipid markers, including TC, HDL-C, TG, phospholipids, and free fatty acids. Therefore, increased serum LCAT activities may play a pivotal role in the development of both diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease among various lipid markers [11]. A number of studies have revealed that increased plasma TG concentrations are associated with higher plasma LCAT activity [11, 13–16]. However, in LCAT-deficient humans and animals, plasma TG concentrations were shown to be increased [17, 24–27]. Among these studies, Ng et al. reported significant decreases in fasting plasma insulin and glucose concentrations and an improvement of insulin signaling pathways in LCAT- and LDL receptor-double-knockout mice, despite increased plasma TG concentrations [17, 18]. Therefore, it is unlikely that increased serum LCAT activity causes hypertriglyceridemia [17, 24]; instead, hypertriglyceridemia may facilitate LCAT activity [16]. Li et al. have reported a mechanistic explanation for these results, that the impaired expression of hepatic insulin receptor substrate 2 and its downstream transcription factors promote insulin resistance, at least partially through LCAT-dependent pathways [28]. Taken together, hypertriglyceridemia may cause insulin resistance through LCAT dependent pathways. In addition, lysophosphatidylcholine, which is generated by LCAT, has also been shown to impair insulin signaling [29, 30]. These deleterious effects of lysophosphatidylcholine may contribute to the development of diabetes mellitus.

Increased plasma free fatty acid levels are a cause of insulin resistance [4–6]. However, we did not identify any association between serum free fatty acid levels and the risk of diabetes mellitus. In our study, most of the blood samples were drawn within 8 h of the participants’ last meal. Therefore, dietary fatty acids might influence the association between serum free fatty acid concentrations and the risk of diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, recent studies have also demonstrated that saturated fatty acids can compromise insulin signaling, whereas polyunsaturated fatty acids diminish the deleterious effects of saturated fatty acids on insulin signaling [31, 32]. Therefore, not only fatty acid concentrations but also compositions may be critical for insulin resistance.

We found a significant increased risk of diabetes mellitus in the male population who had higher serum cholesterol esterification rates but not in the female population. These results are different from the results in the animal study based on LCAT- and low-density lipoprotein receptor-double-knockout mice, which indicated improved insulin sensitivities only in female mice [33]. However, we should consider that measuring serum cholesterol esterification rates in a human population is different from a genetically-modified LCAT mass expression in a specific animal model. Therefore, comparing the results from the different subjects and methods may not be appropriate. Nevertheless, we also showed that increased cholesterol esterification rates were associated with future coronary heart disease and sudden death in a general population, which was especially evident in a female population. These gender-specific phenomena have not yet been fully explained. Increased serum cholesterol esterification rates and risks of coronary heart disease and diabetes mellitus are substantially related. However, the mechanisms seem to be different. Further studies are needed to clarify these gender-specific phenomena.

Our study has limitations. The incidence rate of diabetes mellitus in our study seems to be smaller than that of previous reports [34, 35]. However, the cases of diabetes mellitus in our study were identified by self-reported questionnaires. The recent meta-analysis study has shown that the incidence rates of diabetes based on self-reports are smaller than those of laboratory data-based diabetes [36]. In addition, the initial cases of self-reported diagnosed diabetes mellitus in our study were 63 out of 1513 individuals during 11 years of follow-up. Therefore, the incidence rate is not notably different from those of the Japanese population [37–39] or those of the US population based on self-reported diagnosed diabetes [40]. In addition, we further confirmed the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus for each subject using medical records and excluded 17 cases due to not meeting the criteria or due to lack of laboratory tests. This procedure may also contribute to the smaller incidence rate of diabetes mellitus and result in a statistically underpowered analysis.

Conclusions

Increased serum LCAT activities, measured as the serum cholesterol esterification rates, are associated with the future risk of diabetes mellitus in the general population. This association is significant even after adjustment for HbA1c levels and lipid parameters. Our study indicates that among various lipid markers, increased serum LCAT activity may play a pivotal role in the development of diabetes mellitus in the general population.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Wataru Ogawa from the Division of Diabetes and Endocrinology, Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine for his invaluable advice.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Hyogo Medical Association and the Japan Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body-mass index

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- HbA1c

Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c

- IRI

Immunoreactive insulin

- RR

Relative risk

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- TC

Total cholesterol

- 95%CI

95% Confidence interval

Authors’ contributions

ST and YF contributed to the baseline survey. ST conducted the follow-up study, analyzed the data, and wrote and revised the manuscript. TM, YF, TT, TI, and KH contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was originally designed as a cross-sectional survey. Therefore, we carefully explained the significance of the follow-up study and only participants who agreed were enrolled in the study. All study protocols were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Hidaka Medical Center.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ohlson LO, Larsson B, Bjorntorp P, Eriksson H, Svardsudd K, Welin L, Tibblin G, Wilhelmsen L. Risk factors for type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Thirteen and one-half years of follow-up of the participants in a study of Swedish men born in 1913. Diabetologia. 1988;31(11):798–805. doi: 10.1007/BF00277480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haffner SM, Stern MP, Hazuda HP, Mitchell BD, Patterson JK. Cardiovascular risk factors in confirmed prediabetic individuals. Does the clock for coronary heart disease start ticking before the onset of clinical diabetes? JAMA. 1990;263(21):2893–2898. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440210043030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry IJ, Wannamethee SG, Walker MK, Thomson AG, Whincup PH, Shaper AG. Prospective study of risk factors for development of non-insulin dependent diabetes in middle aged British men. BMJ. 1995;310(6979):560–564. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6979.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pankow JS, Duncan BB, Schmidt MI, Ballantyne CM, Couper DJ, Hoogeveen RC, Golden SH. Fasting plasma free fatty acids and risk of type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):77–82. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unger RH. Lipotoxicity in the pathogenesis of obesity-dependent NIDDM: genetic and clinical implications. Diabetes. 1995;44(8):863–870. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.8.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimabukuro M, Zhou YT, Levi M, Unger RH. Fatty acid-induced beta cell apoptosis: a link between obesity and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(5):2498–2502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeFronzo RA. Insulin resistance, lipotoxicity, type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis: the missing links. The Claude Bernard lecture 2009. Diabetologia. 2010;53(7):1270–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1684-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shulman GI. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(2):171–176. doi: 10.1172/JCI10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glomset JA. The plasma lecithins: cholesterol acyltransferase reaction. J Lipid Res. 1968;9(2):155–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akanuma Y, Glomset J. In vitro incorporation of cholesterol-14C into very low density lipoprotein cholesteryl esters. J Lipid Res. 1968;9(5):620–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka S, Yasuda T, Ishida T, Fujioka Y, Tsujino T, Miki T, Hirata K. Increased serum cholesterol esterification rates predict coronary heart disease and sudden death in a general population. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(5):1098–1104. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Jr, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcel YL, Vezina C. Lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase of human plasma. J Biol Chem. 1973;248(23):8254–8259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akanuma Y, Kuzuya T, Hayashi M, Ide T, Kuzuya N. Positive correlation of serum lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase activity with relative body weight. Eur J Clin Investig. 1973;3(2):136–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1973.tb00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallentin L. Lecithin: cholesterol acyl transfer rate in plasma and its relation to lipid and lipoprotein concentrations in primary hyperlipidemia. Atherosclerosis. 1977;26(2):233–248. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(77)90106-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murakami T, Michelagnoli S, Longhi R, Gianfranceschi G, Pazzucconi F, Calabresi L, Sirtori CR, Franceschini G. Triglycerides are major determinants of cholesterol esterification/transfer and HDL remodeling in human plasma. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15(11):1819–1828. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.15.11.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng DS, Xie C, Maguire GF, Zhu X, Ugwu F, Lam E, Connelly PW. Hypertriglyceridemia in lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase-deficient mice is associated with hepatic overproduction of triglycerides, increased lipogenesis, and improved glucose tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(9):7636–7642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng DS. Novel metabolic phenotypes in lecithin cholesterol acyltyransferase-deficient mice. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2018;29(2):104–109. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka S, Miki T, Sha S, Hirata K, Ishikawa Y, Yokoyama M. Serum levels of Thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances are associated with risk of coronary heart disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2011;18(7):584–591. doi: 10.5551/jat.6585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagasaki T, Akanuma Y. A new colorimetric method for the determination of plasma lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase activity. Clin Chim Acta. 1977;75(3):371–375. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(77)90355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stokke KT, Norum KR. Determination of lecithin: cholesterol acyltransfer in human blood plasma. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1971;27(1):21–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Bartholome M, Niedmann D, Wieland H, Seidel D. An optimized method for measuring lecithin : cholesterol acyltransferase activity, independent of the concentration and quality of the physiological substrate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;664(2):327–334. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(81)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobori K, Saito K, Ito S, Kotani K, Manabe M, Kanno T. A new enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with two monoclonal antibodies to specific epitopes measures human lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase. J Lipid Res. 2002;43(2):325–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayyobi AF, McGladdery SH, Chan S, John Mancini GB, Hill JS, Frohlich JJ. Lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) deficiency and risk of vascular disease: 25 year follow-up. Atherosclerosis. 2004;177(2):361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hovingh GK, Hutten BA, Holleboom AG, Petersen W, Rol P, Stalenhoef A, Zwinderman AH, de Groot E, Kastelein Md JJP, Kuivenhoven JA. Compromised LCAT function is associated with increased atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2005;112(6):879–884. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calabresi L, Favari E, Moleri E, Adorni MP, Pedrelli M, Costa S, Jessup W, Gelissen IC, Kovanen PT, Bernini F, et al. Functional LCAT is not required for macrophage cholesterol efflux to human serum. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204(1):141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furbee JW, Sawyer JK, Parks JS. Lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency increases atherosclerosis in the low density lipoprotein receptor and apolipoprotein E knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(5):3511–3519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109883200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li L, Naples M, Song H, Yuan R, Ye F, Shafi S, Adeli K, Ng DS. LCAT-null mice develop improved hepatic insulin sensitivity through altered regulation of transcription factors and suppressors of cytokine signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293(2):E587–E594. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00278.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motley ED, Kabir SM, Gardner CD, Eguchi K, Frank GD, Kuroki T, Ohba M, Yamakawa T, Eguchi S. Lysophosphatidylcholine inhibits insulin-induced Akt activation through protein kinase C-α in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 2002;39(2):508–512. doi: 10.1161/hy02t2.102907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han MS, Lim Y-M, Quan W, Kim JR, Chung KW, Kang M, Kim S, Park SY, Han J-S, Park S-Y, et al. Lysophosphatidylcholine as an effector of fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J Lipid Res. 2011;52(6):1234–1246. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M014787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maedler K, Oberholzer J, Bucher P, Spinas GA, Donath MY. Monounsaturated fatty acids prevent the deleterious effects of palmitate and high glucose on human pancreatic β-cell turnover and function. Diabetes. 2003;52(3):726–733. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato T, Shimano H, Yamamoto T, Ishikawa M, Kumadaki S, Matsuzaka T, Nakagawa Y, Yahagi N, Nakakuki M, Hasty AH, et al. Palmitate impairs and Eicosapentaenoate restores insulin secretion through regulation of SREBP-1c in pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2008;57(9):2382–2392. doi: 10.2337/db06-1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Hossain MA, Sadat S, Hager L, Liu L, Tam L, Schroer S, Huogen L, Fantus IG, Connelly PW, et al. Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase null mice are protected from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in a gender-specific manner through multiple pathways. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(20):17809–17820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.180893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kameda W, Daimon M, Oizumi T, Jimbu Y, Kimura M, Hirata A, Yamaguchi H, Ohnuma H, Igarashi M, Tominaga M, et al. Association of decrease in serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels with the progression to type 2 diabetes in men of a Japanese population: the Funagata study. Metabolism. 2005;54(5):669–676. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doi Y, Ninomiya T, Hirakawa Y, Takahashi O, Mukai N, Hata J, Iwase M, Kitazono T, Oike Y, Kiyohara Y. Angiopoietin-like protein 2 and risk of type 2 diabetes in a general Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(1):98–100. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goto A, Goto M, Noda M, Tsugane S. Incidence of type 2 diabetes in Japan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oba S, Nagata C, Nakamura K, Fujii K, Kawachi T, Takatsuka N, Shimizu H. Consumption of coffee, green tea, oolong tea, black tea, chocolate snacks and the caffeine content in relation to risk of diabetes in Japanese men and women. Br J Nutr. 2010;103(3):453–459. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509991966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurotani K, Nanri A, Goto A, Mizoue T, Noda M, Kato M, Inoue M, Tsugane S. Vegetable and fruit intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: Japan public health center-based prospective study. Br J Nutr. 2013;109(4):709–717. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512001705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iso H, Date C, Wakai K, Fukui M, Tamakoshi A. The relationship between green tea and total caffeine intake and risk for self-reported type 2 diabetes among Japanese adults. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):554–562. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geiss LS, Pan L, Cadwell B, Gregg EW, Benjamin SM, Engelgau MM. Changes in incidence of diabetes in U.S. adults, 1997-2003. Am J Prevent Med. 2006;30(5):371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.