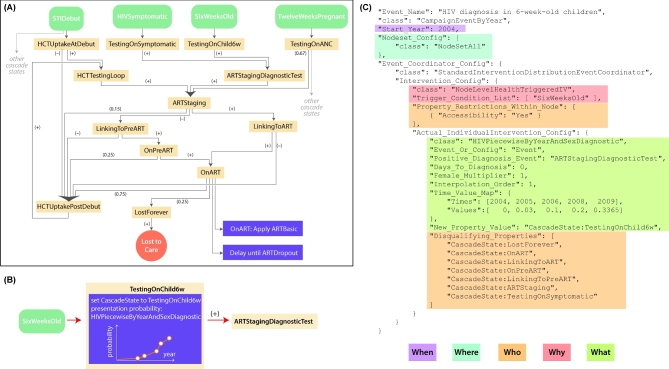

Figure 7.

Example of a typical user-defined set of health-seeking and health care patterns. These components, sequences of flow between them, and parameters governing their effects are provided by the user and fully configurable. Panel (a) shows a schematic of the HIV interventions related to HIV testing and treatment, which are provided as input into the EMOD model for HIV in South Africa. It is composed of many individual building blocks, diagramed here as purple boxes in (b) and encoded as JSON objects as in (c). The sub-section of (a) that is expanded in (b) and (c) is HIV testing of children. The building blocks specify the time that the intervention becomes available (Start_Year); the target population based on socio-demographic strata such as age, sex, location and user-defined characteristics such as risk group or accessibility (‘Accessibility’: ‘Yes’); and the triggering condition for the intervention to be applied, if any. The triggering condition can be one arising from the internal dynamics of the model (such as becoming six weeks of age, as in the example above, ‘SixWeeksOld’) or can be a user-defined event arising from another building block (such as the output of the example above, ‘ARTStagingDiagnostic Test,’ which will trigger the next event to happen as shown by the red arrow in (b)). Building blocks may act as probabilistic decisions, delays, diagnostics and interventions. Some building blocks allow for additional user input, for example, the probabilistic decision of whether to be tested for HIV in (b) and (c) allows user to input a time-series for the probability of HIV testing. EMOD will linearly interpolate the time-series to assign a probability at each simulation time step, as shown in the orange graph in (b).