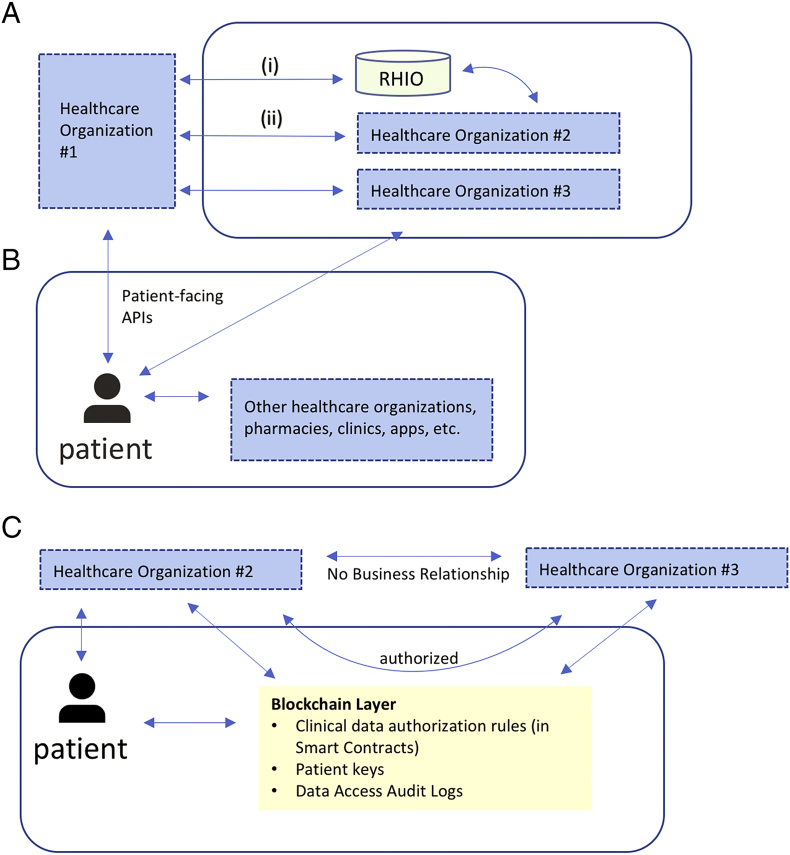

Fig. 1.

(A) Example of institution-driven interoperability for clinical EHR data. Bi-directional clinical data exchange occurs (i) through an intermediary like a Regional Health Information Organization (RHIO) or (ii) directly between health care organizations with specific business agreements. In both cases, data interfaces are entity-to-entity, not entity-to-patient. In this example, since organization #2 and #3 do not have a specific relationship, there is no bi-directional data flow; providers from organization #2 can request data from organization #3 via one-off requests (like a fax). If a patient receives care at all three organizations, their health data will be scattered across all three EHRs.

(B) Example of patient-driven interoperability. Data sharing centers on the patient; in this example, using patient-facing APIs, a patient can directly retrieve their clinical EHR data from organization #1 and organization #3. Once retrieved, the patient can share with other organizations directly. Data flow can be bidirectional. RHIOs and entity-to-entity relationships may still exist as parallel functions.

(C) Blockchain-enabled patient-driven interoperability. In this example, the patient can still retrieve data directly from organization #2; however, through blockchain-enabled smart contracts, the patient can authorize sharing of clinical EHR data between organization #2 and organization #3, which do not have a formal business relationship. The blockchain layer stores these authorization rules, along with patient public keys (to ensure entity resolution), as well as data access audit logs. Each organization will manage linking a patient's public key to their own internal enterprise master patient index system independently, and patients can update the smart contract-driven authorization rules as appropriate (for example, adding a new institution if they are seeing a new provider).