Abstract

Background

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) enables accurate pathological evaluation and low recurrence rates. Large series describing ESD outcomes in Western countries are scarce.

Objective

To evaluate the real-life experience of ESD in a single Western centre.

Methods

Data of all the patients submitted to ESD in our centre were prospectively recorded in a database, from the first procedure in 2011 until May 2017. Feasibility, en bloc and R0 resection rates and safety were assessed.

Results

Three hundred and one ESDs were performed (37 in submucosal lesions) on 283 patients (54% male). Lesions were located in the oesophagus (n = 13), stomach (n = 169), duodenum (n = 4), colon (n = 35) and rectum (n = 80). ESD was technically successful in 292 lesions (97%); among malignant or premalignant epithelial lesions (n = 232), the en bloc resection rate was 91% and, of those, the R0 resection rate was 87% (between 69% in the colon and 93% in the stomach). Two patients needed surgery due to adverse events. Surgery for non-curative ESD was performed in 12 cases (58% without residual lesion). There were 10 perforations, 9 of them closed endoscopically. Mortality was 0%.

Conclusion

Our real-life experience shows that ESD is feasible, safe and effective in Western settings.

Keywords: Endoscopic submucosal dissection, Western real-life experience

Key summary

- The established knowledge on this subject:

- ESD is a well-established method for the treatment of gastrointestinal lesions

- There are few Western referral centres for ESD and large series are scarce

- ESD in some situations, as in subepithelial and non-gastric lesions, are even less reported in Western settings.

- The significant and/or new findings of this study:

- This is the biggest Western ESD series

- This is the first series reporting real-life experience, from the first procedure, and including all consecutive ESDs performed in a gastroenterology department

- From the early stages of implementation of ESD in a Western gastroenterology referral centre, this technique can be secure and efficient.

Introduction

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are well-established methods for the treatment of gastrointestinal malignant and premalignant lesions. As en bloc resection is preferable since it allows a precise histological evaluation and leads to lower rates of local recurrence,1,2 ESD has advantages over EMR in larger lesions. This technique was initially developed for early gastric cancer, but its use has been generalized for other organs and lesions, particularly in high-volume centres. ESD demands more advanced endoscopic skills, has a long learning curve3 and higher rates of adverse events.1

Large Eastern studies have been published confirming its efficacy in the treatment of malignant and premalignant lesions along the gastrointestinal tract.4–6 Western data is still scarce, particularly outside the stomach. The overall ESD experience in Europe and the USA is still low, due to the lower incidence of gastric cancer and the lesser capability of identifying dysplastic lesions compared with Eastern centres.7 Therefore, in order to assess the feasibility, efficacy and safety of this procedure in Western countries, experience from large centres is very valuable.

ESD for subepithelial lesions is even more rarely reported in the West. No guidelines are available, and outcomes and safety are largely unknown.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of our real-life experience of ESD along the gastrointestinal tract, measuring outcomes as en bloc and complete resections, adverse events and mortality.

Methods

Patient selection

ESD was performed on patients followed in the outpatient clinic or referred to our centre, between January 2011 and May 2017.

Lesions selected for ESD included neoplastic oesophageal lesions, gastric dysplastic/malignant lesions of any size (or below 3 cm if ulcerated according to expanded indications8) and duodenal or colorectal neoplasia that were well differentiated, had no endoscopic suspicion of deep submucosal invasion and were unsuitable for en bloc EMR. Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated lesions were not considered for ESD. Symptomatic subepithelial lesions (dysphagia or bleeding), or which diagnosis was not conclusive by Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) or ‘bite-on-bite’ biopsies, were also considered for ESD if located in the muscularis mucosa or submucosa, after EUS evaluation.

ESD technique

Lesions were evaluated using high-definition endoscopy. ESDs were performed by three endoscopists, FBS, MM and JSA, who have done more than 5000 upper endoscopies and 5000 colonoscopies, and had large experience in therapeutic endoscopy: JSA spent three months and FBS one month in Japan learning ESD from Japanese experts.

Epithelial lesions were assessed using dye chromoendoscopy (lugol for oesophageal Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), acetic acid and indigo carmine for gastric lesions and indigo carmine for colorectal lesions) and virtual chromoendoscopy with narrow-band imaging (NBI). Small dots were done around oesophageal and gastric lesions, using a dual-knife. A solution of saline, indigo carmine, methylcellulose and diluted adrenaline was used for submucosal lifting. Dissection was performed using 1.5 or 2 mm dual-knives for mucosal incision. Dual-knives, insulated tip (IT)-2 or IT-nano knives (Olympus®, Tokyo, Japan) were used for submucosal dissection. Erbe ICC-200 or ICC-300 electrosurgical units (ERBE® Elektromedizin GmBH, Tubingen, Germany) were used. A coagrasper (Olympus®, Tokyo, Japan) was used for hemostasis whenever necessary.

Patients who underwent gastric or oesophageal ESD were treated with esomeprazole 40 mg b.i.d. for 8 weeks, with no oral diet in the 12 hours after the procedure, a liquid diet during the following 3 days and progressive return to a normal diet.

Histopathological evaluation

ESD specimens were sent to pathology for evaluation with pins on a cork plate, fixed in formalin. Sectioning at 2 mm intervals were performed to evaluate lateral and vertical margins. All the specimens were analysed by two expert gastrointestinal pathologists.

Definitions and outcomes

En bloc resection was considered when the target lesion was retrieved in a single specimen, or considered a piecemeal resection if the lesion was removed in more than one fragment. The procedure was considered to be a failure if the target lesion was not removed. R0 resection was considered when histopathological evaluation showed free horizontal and vertical margins; otherwise, R1 resection was defined.

Curative resections were those intramucosal and R0 or those with superficial submucosal invasion, low risk on histological criteria and R0, according to the respective organ. For oesophageal SCC, curative resection was considered if the lesions were classified as a pT1a or T1b/sm1 (<200 µm) without lymphovascular invasion, differentiated type, R0 resection. For Barrett’s neoplasia, curative resection was considered if lesions were pT1a or T1b/sm1 (<500 µm) without lymphovascular invasion, differentiated type, R0 resection. Regarding gastric epithelial lesions, R0 resections of low- or high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or of differentiated intestinal mucosal or superficial submucosal (sm1, < 500 µm) adenocarcinoma without lymphovascular invasion were considered curative. Colorectal curative resections were considered if R0, with low-grade dysplasia (LGD) or HGD or differentiated-type mucosal or superficial submucosal (sm1, < 1000 µm) adenocarcinoma without lymphovascular invasion.

Adverse events

Immediate perforation was defined as a defect in the wall that allowed the visualization of intra-abdominal space or mesenteric fat. Delayed perforation was defined as the appearance of signs of perforation postoperatively in an uneventful procedure.

Immediate severe bleeding was defined as bleeding during the procedure that was not possible to control endoscopically or if it caused hemodynamic instability. Non-severe bleeding during the procedure that was immediately manageable endoscopically was not considered an adverse event. Delayed bleeding was defined as bleeding from the surgical site, postoperatively.

All the patients were posteriorly followed in the outpatient clinic, and endoscopic follow-up was performed as appropriate.8 Procedure-related mortality was defined as any death consequent to the ESD procedure.

Statistical analysis

All data was collected prospectively in a database.

Categorical variables were described as absolute (n) and relative frequencies (%). Mean and standard deviation or median and percentiles were used for continuous variables as appropriate. When testing a hypothesis about continuous variables, Mann–Whitney nonparametric tests were used as appropriate, taking into account normality assumptions and the number of groups compared. When testing a hypothesis about categorical variables a chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used, as appropriate. The significance level used was 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v.22.0.

Results

During the 77 months of analysis, 301 ESDs were performed (Figures 1–3), which can be analysed in Table 1. Among the colorectal lateral spreading tumours, 71% were granular nodular mixed type, 21% were granular homogeneous type, 6% non-granular flat elevated type and 2% non-granular pseudo-depressed type. Among gastric lesions, the Paris classification was Is (16%), IIa (38%), IIb (6%), IIc (1%) and IIa+IIc (39%). SCC was a IIb 4 x 3 cm lesion and Barrett lesions were IIa or IIb (50% each); duodenal lesions were IIa.

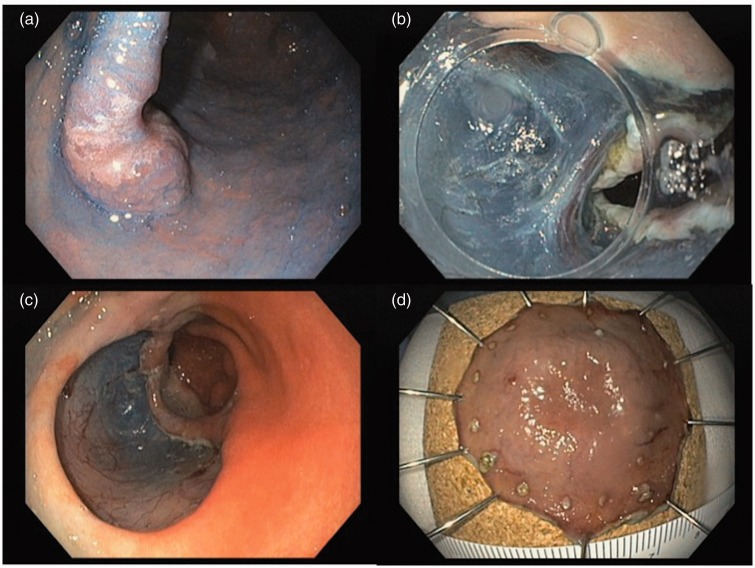

Figure 1.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection of a Paris IIa+IIc gastric lesion (high-grade dysplasia, free margins). a: lesion evaluated after acetic acid and indigo carmine; b: submucosal dissection; c: lesion site after ESD; d: piece fixed in cork for pathological evaluation.

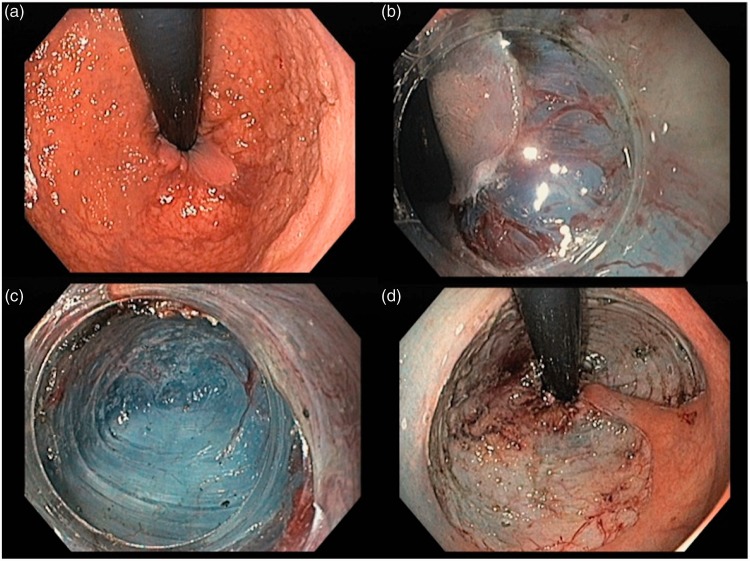

Figure 2.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection of a sigmoid lateral spreading tumour granular nodular mixed type (high-grade dysplasia, en-bloc resection, free margins). a: proximal margin of the lesion in retroflexed position; b: pocket method, with tunnel creation; c: image inside the pocket; d: lesion site after en-bloc ESD.

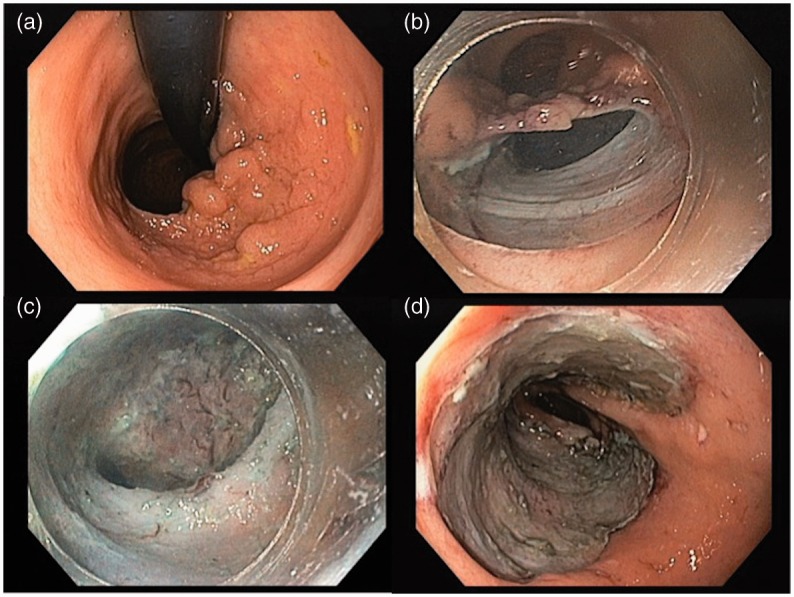

Figure 3.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection of a rectal lateral spreading tumour, granular homogeneous type, occupying nearly 90% of the rectal circumference (low-grade dysplasia, en-bloc resection, free margins). a: lesion observed in retroflexed position; b: anal margin, with dissection of anal mucosa; c: pocket creation; d: lesion site after ESD.

Table 1.

Description of the patients and lesions removed by ESD (301 lesions in 283 patients).

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Male Gender (n, %) | 162 (54) |

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 64 ± 13 |

| Antiplatelets (n, %) | 41 (14) |

| Anticoagulants (n, %) | 13 (4) |

| Lesion location (n, %) | |

| - oesophagus | 13 (4) |

| - stomach | 169 (56) |

| - duodenum | 4 (1) |

| - colon | 35 (12) |

| - rectum | 80 (27) |

| Lesion size, mm (mean, SD) | |

| - overall | 39 ± 19 |

| - oesophagus | 41 ± 37 |

| - stomach | 38 ± 18 |

| - duodenum | 16 ± 11 |

| - colon | 36 ± 16 |

| - rectum | 43 ± 21 |

| Procedure time, min (mean, SD) | |

| - overall | 119 ± 85 |

| - oesophagus | 180 ± 97 |

| - stomach | 85 ± 78 |

| - duodenum | 135 ± 71 |

| - colon | 135 ± 63 |

| - rectum | 105 ± 100 |

| Dissection device | |

| - dual-knife only | 116 (39) |

| - dual-knife + IT-knife | 173 (57) |

| - knife + snare (hybrid) | 12 (4) |

ESD was not possible in 9 (3%) cases: 5 due to technical difficulties in completing the dissection (1 in the ascending colon, 1 in the sigmoid colon, 1 in the rectum and 2 in the gastric incisura) and 4 due to perforation (2 in the sigmoid, 1 in the oesophagus and 1 in the upper greater curvature of the stomach). Two patients (0.7%) needed surgery due to a complication related to ESD, namely a delayed gastric bleeding and one gastric perforation. Both patients were discharged up to seven days after admission for ESD. There were 10 perforations overall (3.3%), 9 of them treated endoscopically with clips during the procedure and managed conservatively. We had no cases of severe immediate bleeding, and none of them required blood transfusion. Procedure-related mortality was 0%.

From the 301 ESDs, 264 (88%) were performed on epithelial lesions. Excluding ESD failures and those in which histological examination revealed non-neoplastic lesions (n = 23), we had a total of 232 dysplastic or malignant epithelial lesions (64 adenocarcinomas, 74 HGD, 93 LGD and 1 squamous cell cancer). From those, the en bloc rate was 91% overall, and extra-gastric location was a risk factor for piecemeal resection (Table 2). Among en bloc resections (n = 210), R0 was achieved in 87% overall.

Table 2.

En bloc resection rates of ESD performed on epithelial neoplastic lesions (n = 232).

| En bloc resection |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| % | p | OR (CI 95%)φ | |

| Local (n) | 0.001 | ||

| . Oesophagus (7) | 86 | 4.875 (0.470–50.601) | |

| . Stomach (121) | 97 | ref | |

| . Colon (31) | 87 | 5.625 (1.413–22.398) | |

| . Rectum (70) | 86 | 4.875 (1.467–16.195) | |

| . Duodenum (3) | 33 | 58.5 (4.349–796.930) | |

| Lesion > 30 mm (146) | 93 vs 87* | 0.187* | |

| . Oesophagus (3) | 100 vs 75* | 1.000* | - |

| . Stomach (78) | 95 vs 98* | 0.653* | ref |

| . Colon (16) | 94 vs 79* | 0.315* | 1.233 (0.129–11.825) |

| . Rectum (49) | 88 vs 81* | 0.473* | 2.581 (0.690–9.661) |

| . Duodenum (0)** | - | - | - |

| IT-knife (136)*** | 88 vs 94 | 0.170 | - |

Versus smaller or equal to 30 mm;

No lesions larger than 30 mm;

Versus dual-knife;

φRisk of not achieving en bloc resection (reference – gastric ESDs).

We observed some differences regarding ESD outcomes in the three main organs (Table 3). In the stomach, en bloc, R0 and curative resection were significantly higher (97%, 93% and 92% respectively) than in the other organs. In the rectum, we also achieved high rates of en bloc (86%) and R0 resections (85%); the curative rate dropped to 80% because of lesions that were completely resected but did not fulfil all the criteria of curative resection (see below). In the colon we had the lowest rate of cure (69%) despite the high rate of en-bloc resection (87%); this was due to the high number of colonic ESDs with positive horizontal and deep margins (n = 9).

Table 3.

R0 and curative resection rates of en-bloc ESDs performed on epithelial dysplastic or malignant lesions (n = 210).

| R0 resection |

Curative resection |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | p | OR (CI 95%)** | % | p | OR (CI 95%)** | |

| Local (n) | 0.001 | 0.020 | ||||

| . Oesophagus (6) | 67 | 6.813 (1.079–43.023) | 67 | 3.900 (1.087–13.991) | ||

| . Stomach (117) | 93 | ref | 92 | ref | ||

| . Colon (26) | 69 | 6.056 (2.017–18.184) | 69 | 3.600 (1.575–8.230) | ||

| . Rectum (60) | 85 | 2.404 (0.877–6.593) | 80 | 2.340 (1.073–5.101) | ||

| . Duodenum (1) | 0 | - | 0 | - | ||

| Lesion > 30 mm (135) | 87 vs 87* | 1.000* | 8.750 (0.648–118.203) | 84 vs 87* | 0.567* | |

| . Oesophagus (3) | 67 vs 67* | 1.000* | ref | 67 vs 67* | 1.000* | 4.933 (0.807-30.155) |

| . Stomach (74) | 95 vs 91* | 0.463* | 11.667 (2.756–49.391) | 93 vs 91* | 0.723* | ref |

| . Colon (15) | 60 vs 82* | 0.395* | 3.403 (0.934–12.393) | 60 vs 82* | 0.395* | 5.920 (2.074-16.901) |

| . Rectum (43) | 84 vs 88* | 1.000* | - | 76 vs 88* | 0.479* | 3.442 (1.259-9.408) |

| . Duodenum (1) | 0 | - | 0 | - | - | |

| IT-knife (81)*** | 79 vs 98 | 0.009 | 14.078 (1.813–109-289) | 77 vs 94 | 0.006 | 4.222 (1.313–13.576) |

Versus smaller or equal to 30 mm;

Risk of not achieving R0 or curative resection;

Versus dual-knife.

Of the R0 resections, only three had no criteria for curative resection (a gastric and a rectal adenocarcinoma with lymphatic invasion on histological evaluation and a rectal adenocarcinoma with 1.5 mm of deep submucosal invasion). Among en bloc, R1 resected lesions (n = 28), 23 had positive lateral margins (1/6 in the oesophagus, 8/117 in the stomach, 6/26 in the colon, 7/60 in the rectum and 1/1 in duodenum) and 7 had positive deep margins (2 in the oesophagus, 1 in the stomach, 3 in the colon and 1 in the rectum). Considering only the last two years of experience (from May 2015 to May 2017), we report three failures, an en bloc resection rate of 96% and a R0 resection rate of 95% in the stomach (60 in 63 lesions), 93% in the rectum (42 in 45 lesions) and 100% in the colon (only three lesions); no ESDs on epithelial lesions in the esophagus or duodenum were performed during this period.

Regarding subepithelial lesions (n = 37), we had one ESD failure due to an oesophageal perforation that was treated endoscopically and managed conservatively. We had 10 gastric inflammatory polyps, 6 ectopic pancreas, 5 rectal neuroendocrine tumors, 5 lypomas (1 oesophagus, 4 stomach), 4 oesophageal leiomyomas, 2 oesophageal schwannomas, 2 oesophageal granular cell tumours, 1 gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), 1 rectal cyst and 1 rectal calcified pseudo-tumour. None of the procedures required further surgical treatment: the gastric GIST ESD was an R1 resection but was under surveillance since histological evaluation showed very low risk of progression.

Surgery was performed on 7 patients due to ESD failure and in 12 patients due to R1 resection (n = 3: 1 in the oesophagus, 1 in the stomach and 1 in the colon), massive submucosal invasion (n = 7: 2 in the stomach, 2 in the rectum and 3 in the colon), lymphatic invasion (n = 1: stomach) or tumour budding (n = 1: rectum). Among those 12 lesions, 7 (1 in the oesophagus, 1 the stomach, 1 in the rectum and 4 in the colon) did not have neoplasia in the surgical specimens and were free of disease at follow-up. In the remaining R1 resections, surveillance was decided after multidisciplinary evaluation; from those, local recurrence was found in 3 cases (1 in the gastric antrum, 1 in the colon and 1 in the rectum) that were treated endoscopically, without the need for surgery. No local recurrence was found among R0 resections; one patient with a well-differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma treated by ESD needed surgery due to a metachronous, gastric adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells.

From all the epithelial lesions with successful ESD (n = 256), 174 (68%) had previous biopsies (Table 4). Among them, 49 malignant lesions were diagnosed on ESD, but only 15 of those had malignancy in the biopsies. Also, from the ESDs that showed non-neoplastic lesions (n = 23), 10 had had LGD or HGD on biopsies; the remaining lesions did not show dysplasia on biopsy, or had not had previous biopsies but ESD was decided due to the endoscopic suspicion of a premalignant lesion.

Table 4.

Relationship between biopsies and ESD histology.

| Biopsies | ESD histology |

Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma | SCC | HGD | LGD | Hyperplasia | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 14 | - | - | 1 | - | 15 |

| SCC | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| HGD | 20 | - | 13 | 11 | 2 | 45 |

| LGD | 14 | - | 29 | 50 | 8 | 102 |

| Hyperplasia | - | - | - | 2 | 9 | 11 |

| Total | 48 | 1 | 42 | 64 | 19 | 174 |

SCC: squamous cell carcinoma; HGD: high-grade dysplasia; LGD: low-grade dysplasia.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the largest ESD series from a single centre in a Western setting. Overall, ESD was a very secure procedure: no deaths occurred and the rate of serious adverse events requiring surgery was very low (0.7%). Feasibility was very high (97%).

Our study is different from other published studies since it is well representative of the experience of a large referral tertiary centre, as it includes different types of lesions (epithelial and subepithelial) along different organs of the gastrointestinal tract. All the patients who underwent ESD in our centre were included starting in case one. The fact that we analysed our experience from our first ESD, means that good results could be achieved from the early stages of the learning curve. We did, however, implement this technique in a step-by-step approach, according to the Japanese experience. First, ESD was performed on epithelial lesions in the stomach; later, rectal lesions were included, after that oesophageal neoplasia and finally colonic and subepithelial lesions. It means that good results could be achieved from the early stages of the learning curve but on the other hand, it could justify why we had a considerable rate of R1 resections. We think that even better results will be achievable, as demonstrated by the improvement over the last two years.

Our study is similar to other Western studies regarding en bloc/R0 resections in gastric lesions, reporting en bloc rates between 93 and 100%, R0 resections between 91 and 93% and curative resection rates higher than 83%.9-12 In the last two years of experience we achieved even higher rates of R0 resection (95%).

Western studies regarding outcomes on colonic lesions are much more scarce. The larger study is a single-centre evaluation of 182 colorectal lesions (119 in the colon), reporting feasibility of 85%, en bloc resection of 88% and a 63% R0 resection rate.13 We were able to achieve in the colon 87% of en bloc resection rate but, from those, only 69% were R0. Among non-curative resections in the colon, four needed surgery due to adenocarcinoma (none with malignancy in the surgical specimen) and the remaining were under surveillance. Our results are similar in the rectum regarding en bloc resection, but with a higher percentage of R0 resection (85%).

Duodenal ESD is not encouraged by European guidelines8 due to the high rate of adverse events. One study14 that analysed a hybrid ESD–EMR technique for duodenal adenomas did not show any benefit over EMR. A review on endoscopic treatment of non-ampullary duodenal adenomas15 reports good results overall, with a complete resection rate of almost 100%, but with adverse events in up to one-third of the cases. From our three duodenal ESDs, we did not experience any adverse event, but en bloc resection was only achieved in one case, and without R0 resection.

Among non-curative resections overall, 12 were operated on, but only 5 had dysplasia/malignancy in the surgical specimen. Regarding en bloc R1 resections, it was interesting to analyse whether they were due to the presence of the lesion in the lateral or in the deep margin. In the former case it could represent a failure to accurately determine the margins of the lesion, or technical difficulties during ESD; in the latter, it represents a failure of the endoscopic evaluation of the lesions regarding the prediction of submucosal invasion depth. ESD in the duodenum (100%) and colon (23%) showed the highest rates of en bloc resections with positive lateral margins; since the margins in these locations are usually easy to delineate with chromoendoscopy, we assume that they were due to technical difficulties. Among en bloc resections with positive lateral margins and free deep margins only one needed surgery, and only one other had local recurrence after ESD, treated with ESD. The remaining patients did not show recurrence during follow-up.

In the West, the selection of lesions for ESD is still very dependent on biopsies, because endoscopists do not have the accuracy of their Japanese counterparts on the evaluation of a target lesion. We analysed the differences between pre- and post-ESD histology. Less than one-third of adenocarcinomas had this diagnosis before ESD and, among 43 LGD on biopsies, 29 were in fact HGD and almost a half of the HGD were adenocarcinomas. These substantial differences could be due to the difficulty of evaluating dysplasia on biopsies by pathologists and also to the inaccurate sampling, even when using NBI.

A Western series16 of 37 subepithelial tumours treated with ESD reported an overall R0 resection rate of 81.1% (100% in those from the submucosa and only 68.2% in those from the muscularis propria). From our 37 subepithelial lesions, 4 were R1 resections, but none was clinically significant: 2 were related to ESD on the ectopic pancreas (deep involvement of the muscularis propria) and one in a 14 cm symptomatic oesophageal lipoma (piecemeal resection); the other R1 resection was in a GIST that endoscopically was entirely removed, but the deep margins were not considered free upon histological evaluation. ESD is useful for the treatment of symptomatic benign or potentially malignant subepithelial lesions and, in selected cases, for diagnosis, if other techniques are not conclusive.

Our study has some limitations. It is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data; we think that the assessment of our global experience is reliable, since the data was prospectively recorded in a database, avoiding retrospective search of clinical data. Also, three endoscopists with different training and methodologies performed the ESDs, and a very different range of lesions was included; this heterogeneity turns the interpretation of data more difficult, but this is not possible to avoid when the main purpose is to describe the overall experience of a tertiary centre.

In conclusion, ESD is a safe and effective treatment of premalignant and malignant epithelial lesions, and of subepithelial tumours, particularly in the stomach. Our study shows that good results should be achieved even in the early stages of ESD implementation in Western centres.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This is a non-interventional observational study, which conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1974 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved 10 January 2012 (ethics reference number 15/2012) by the ethical review board of the Centro Hospitalar S. João.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained for every patient before ESD.

References

- 1.Fujiya M, Tanaka K, Dokoshi T, et al. Efficacy and adverse events of EMR and endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of colon neoplasms: a meta-analysis of studies comparing EMR and endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81: 583–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park YM, Cho E, Kang HY, et al. The effectiveness and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Surgic Endosc 2011; 25: 2666–2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong KH, Shin SJ, Kim JH. Learning curve for endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasms. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 26: 949–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsujii Y, Nishida T, Nishiyama O, et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal neoplasms: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Endoscopy 2015; 47: 775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashi Y, Shinozaki S, Sunada K, et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial colorectal tumors more than 50 mm in diameter. Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 83(3): 602–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin KY, Jeon SW, Cho KB, et al. Clinical outcomes of the endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer are comparable between absolute and new expanded criteria. Gut Liver 2015; 9: 181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oyama T, Yahagi N, Ponchon T, et al. How to establish endoscopic submucosal dissection in Western countries. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21: 11209–11220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy 2015; 47: 829–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emura F, Mejia J, Donneys A, et al. Therapeutic outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection of differentiated early gastric cancer in a Western endoscopy setting (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 82: 804–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Repici A, Zullo A, Hassan C, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric neoplastic lesions: a Western series. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepat 2013; 25: 1261–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pimentel-Nunes P, Mourao F, Veloso N, et al. Long-term follow-up after endoscopic resection of gastric superficial neoplastic lesions in Portugal. Endoscopy 2014; 46: 933–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aslan F, Alper E, Cekic C, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric lesions: the 100 cases experience from a tertiary reference center in West. Scand J Gastroenterol 2015; 50: 368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sauer M, Hildebrand R, Oyama T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for flat or sessile colorectal neoplasia >20 mm: A European single-center series of 182 cases. Endosc Int Open 2016; 4: E895–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basford PJ, George R, Nixon E, et al. Endoscopic resection of sporadic duodenal adenomas: comparison of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) with hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) techniques and the risks of late delayed bleeding. Surg Endosc 2014; 28: 1594–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marques J, Baldaque-Silva F, Pereira P, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection in the treatment of sporadic nonampullary duodenal adenomatous polyps. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7: 720–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bialek A, Wiechowska-Kozlowska A, Pertkiewicz J, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for treatment of gastric subepithelial tumors (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75: 276–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]