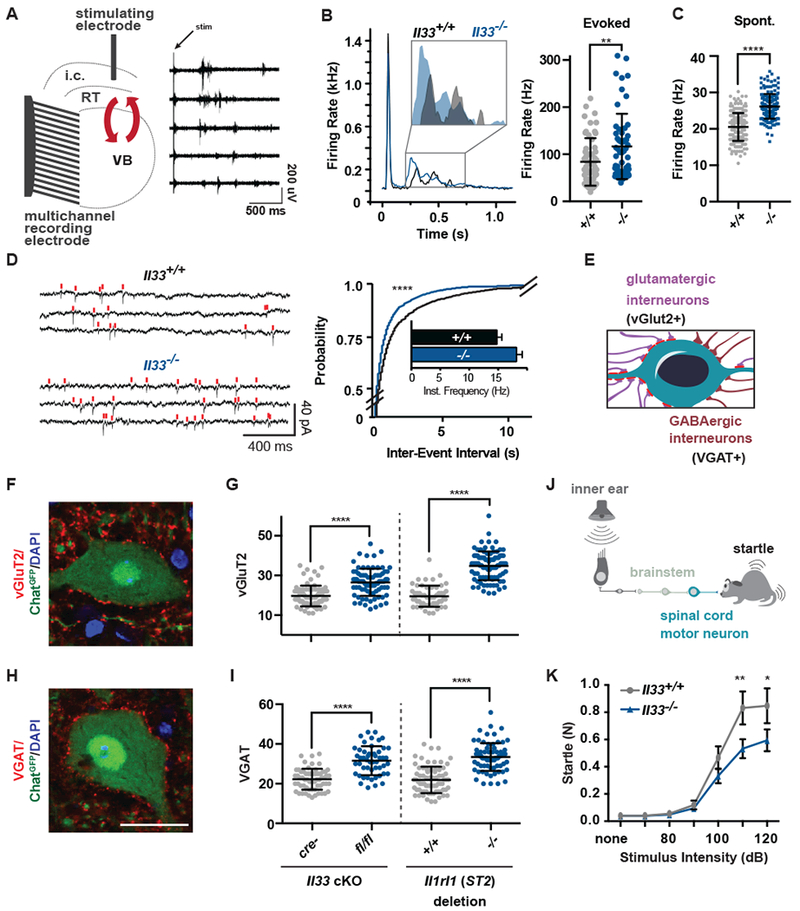

Figure 2: IL-33 deficiency leads to excess synapses and abnormal thalamic and sensorimotor circuit function.

(A) Schematic of extracellular recording setup to measure circuit activity between ventrobasal (VB) and reticular thalamic nuclei (RT) with representative recording showing activity in five channels after stimulation of the internal capsule (i.c.) that contains cortical afferents. Red arrows indicate reciprocal VB-RT connections. (B) Average traces and quantification of mean firing rates reveal higher evoked firing in Il33−/−. (C) Quantification of mean firing rates in the absence of stimulation reveals increased spontaneous firing in Il33−/−. (D) Representative traces and quantification of intracellular patch-clamp recordings from neurons in the VB show increased miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) in Il33−/−. (E) Schematic of motor neuron synaptic afferents. (F, G) Representative image and quantification of excitatory inputs per motor neuron after conditional deletion of Il33 (hGFAPcre) or global deletion of Il1rl1. (H, I) Inhibitory (VGAT+) inputs in the same mice (scale = 25 µm). (J) Schematic of startle pathway. (K) Impaired sensorimotor startle in Il33−/− animals. Statistics: Data in B-C from WT: n=6-8 slices, 2 mice. KO: n=14-15 slices, 3 mice, points are individual recordings. Data in B analyzed by Mann-Whitney and C with student’s t test. Data in D from n=23-25 cells and 3-4 mice/group analyzed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Data in F - I from n=3 animals, >75 neurons per genotype, student’s t-test; points are individual neurons. K is n=12/group, two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<.0001. B-I are mean±SD, K is mean±SEM.