Efficient delivery of pDNA using SWNT–succinate–PEI conjugates.

Efficient delivery of pDNA using SWNT–succinate–PEI conjugates.

Abstract

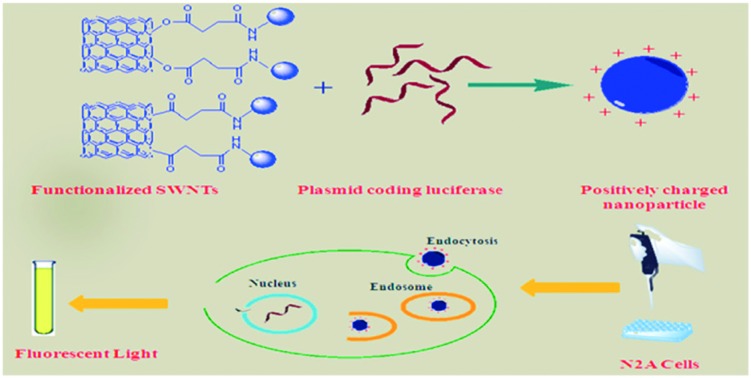

Polyethylenimine (PEI) is a widely used non-viral vector for DNA delivery. One major obstacle of higher molecular weight PEIs is the increased cytotoxicity despite the improved transfection efficiency and numerous chemical modifications that have been reported to overcome this problem. Carbon nanotubes (CNT) are carbon nanomaterials capable of penetrating into cell membranes with no cytotoxic effects. Covalent and noncovalent functionalization methods have been used to improve their solubility in aqueous media. The idea of conjugating PEIs and CNT through different chemical bonds and linkers seems promising as it may result in highly effective carriers due to combination of the transfection ability of PEI with cell internalization of CNT. In this study, six different water-soluble PEI conjugates of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) were prepared by grafting PEI with one of three molecular weights (1.8, 10 and 25 kDa) through succinate as a linker which refers to “an organic moiety through which a SWNT is conjugated to PEI.” The succinate linker was introduced to the surface of SWNTs through two different chemical strategies: a) ester and b) acyl linkages. The resulting SWNT–PEI vectors were characterized by IR spectroscopy, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and SEM imaging. All synthesized carriers were evaluated and compared for their cytotoxicity and transfection efficiency in murine neuroblastoma cells as polyplexes with plasmid DNA for luciferase and green fluorescent protein (GFP). The most efficient carriers were prepared by attaching PEI with the lowest molecular weight (1.8 kDa) through acyl linkage, which gave a transfection efficiency 190-fold greater than that of the corresponding free PEI. Transfection efficiency was the highest in polyplexes prepared with acyl-linked conjugates in all the plasmid/vector ratios studied.

1. Introduction

Since their discovery by Iijima,1 carbon nanotubes (CNT) have been the subject of a wide range of investigations focusing on their unique properties. Aside from their chemical properties, their nanoscale size, extreme flexibility, high tensile strength, optical activity2 and high conductivity have made them candidates for physical and chemical studies aimed at preparing nano-composites, biosensors3 and field-effect transistors (FETs).4 Although CNTs can penetrate into cell membranes, their low solubility has limited their use in biological applications. The hydrophobic nature of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) renders them insoluble in aqueous media and has prompted attempts to improve their solubility by either non-covalent or covalent functionalization methods.5 In non-covalent functionalization, π–π stacking or hydrophobic interactions enable the binding of surfactants, nucleic acids, peptides, polymers, or oligomers.5 In covalent functionalization, several types of chemical reactions have been used for surface modification of SWNTs, including fluorination, oxidation, ozonolysis, the Bingel reaction, nitrene and carbene addition and 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition.6,7 Polar or charged groups attached to SWNTs by these reactions may either directly enhance solubility or allow the attachment of larger molecules with a greater capacity to enhance solubility.

The ability of SWNTs to enter cells has led to a variety of studies aimed at creating new vehicles for drug,8,9 gene10–15 and protein16 delivery. Unaltered DNA does not form direct π–π stacking or hydrophobic interactions with SWNTs. Fabricating a gene delivery vector from CNT requires incorporating a linkage mechanism, preferably one that both improves water solubility and populates the SWNT surface with positive charges in order to condense plasmid DNA. We recently reported that nanovectors based on non-covalent functionalization of SWNTs with alkylated polyethylenimines are efficient gene vectors in vitro and in a systemic gene delivery system.17 In this study, we investigate the covalent functionalization of SWNTs to increase their transfection properties. Among the polycations available for functionalizing SWNTs, PEI has the advantage of providing high densities of terminal primary amines, and it is one of the most widely used non-viral vectors for transfection studies.18 PEI has been the subject of many chemical modification studies with alkyl groups19 or peptides20–23 aimed at increasing transfection efficiency while lowering cytotoxicity. In the present study, we synthesize a series of DNA nanovectors by covalent conjugation of SWNTs to PEI molecules of different molecular weights through different hydrolysable linkers. This allows us to investigate the effects of polymer size and linker type on DNA transfection efficiency and cytotoxicity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Single-walled carbon nanotubes, 25 kDa branched polyethylenimine, N-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt), and 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), solvents and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Munich, Germany). Branched polyethylenimines (1.8 kDa and 10 kDa PEI) were purchased from Polysciences, Inc. (Warrington, USA). Plasmid pRL-CMV-luc under the control of a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and luciferase assay kits were purchased from Promega (Madison, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from GIBCO (Gaithersburg, USA). Ethidium bromide was purchased from Cinnagen (Tehran, Iran). Dialyses were carried out using Spectra/Por dialysis membranes (Spectrum Laboratories, Houston, USA). PTFE membranes (200 nm) were obtained from Chmlab, Spain. Double distilled water was used as the base solution in all experimental reactions.

2.2. Functionalization of SWNTs

2.2.1. Succinate ester functionalization of SWNTs

Hydroxyl groups were introduced onto the surface of SWNTs by the method of Song et al.24 with minor modifications, and then esterified with succinic anhydride (Fig. 1A). Briefly, SWNT (5 mg) was dispersed in a mixture of 50 ml of ethanol and 10 ml of water containing 250 mg of KOH and sonicated for 20 minutes. The mixture was heated at 75 °C for 24 hours. The reaction mixture was filtered through a 0.2 μm PTFE membrane and the retentate was washed thoroughly with double distilled water. The retained material (SWNT–OH) was dried at 65 °C for 24 hours. Esterification with succinic anhydride was carried out in dichloromethane using 4-dimethylaminopyridine as the catalyst. SWNT–OH (5 mg) was sonicated for 7 minutes in 35 ml of dichloromethane followed by the addition of succinic anhydride (100 mg, 1 mmol) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (122 mg, 1 mmol). The reaction was carried out in an argon atmosphere at room temperature for 72 hours. Dichloromethane was removed using a rotary evaporator. To remove 4-dimethylaminopyridine and unreacted succinic anhydride, 30 ml of water at 0 °C was added and the mixture was filtered through a 0.2 μm PTFE membrane, then the retentate was washed thoroughly with water. The retentate was suspended in water and the mixture was lyophilized.

Fig. 1. The synthetic route to: A) ester-linked SWNT–PEI conjugates (S1.8, S10 and S25) and B) acyl-linked SWNT–PEI conjugates (AC1.8, AC10 and AC25).

2.2.2. Functionalization of SWNTs by Friedel–Crafts acylation

Direct Friedel–Crafts acylation of CNT using polyphosphoric acid was reported previously.25 Accordingly, 15 mg of SWNT was added to a mixture of polyphosphoric acid (5 mg) and P2O5 (1.6 mg) and stirred at 120 °C for 10 minutes to reduce the viscosity. Succinic anhydride (100 mg, 1 mmol) was added gradually to the reaction mixture and stirred for 6 days at 120 °C (Fig. 2iB). After cooling the reaction mixture to room temperature, 5 ml of water was added followed by filtration using a 0.2 μm PTFE membrane. The retentate was washed with several portions of 80 °C water to remove the unreacted and hydrolyzed succinic anhydride and dried at 65 °C for 24 hours.

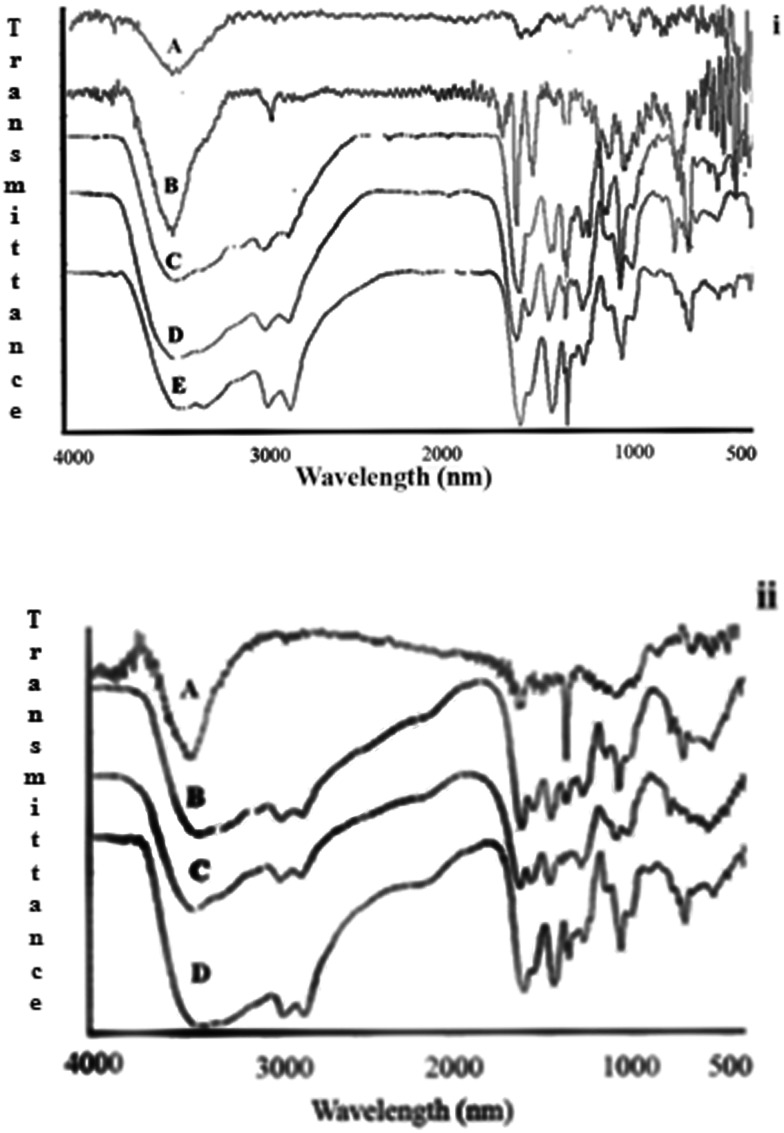

Fig. 2. FTIR spectra of iA) hydroxylated SWNT (1), iB) hydroxylated SWNT with succinate linked through ester groups (2), (3) including: iC) SWNT–ester–PEI1.8 (S1.8), iD) SWNT–ester–PEI10 (S10), and iE) SWNT–ester–PEI25 (S25), and iiA) Friedel–Crafts acylated SWNT with succinic anhydride (4), iiB) SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8, iiC) SWNT–acyl–PEI10, and iiD) SWNT–acyl–PEI25.

2.2.3. Coupling of functionalized SWNTs to PEI

SWNT–ester–COOH (2, 2 mg) or SWNT–acyl–COOH (4, 6 mg) was dispersed in 8 ml of water by sonication, then EDC (240 mg) was added and the mixture was stirred for 45 minutes at room temperature. PEI (1.8 kDa, 160 mg) and HOBt (168.8 mg) dissolved in 7 ml of water were added dropwise and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 days (Fig. 1A and B).

Solubilized PEI-grafted SWNTs were separated from the reaction mixture by filtering through a 200 nm PTFE membrane and further purified by dialysis against 3 L of distilled water three times using a Spectra/Por® (3500 MWCO) membrane to remove the reactants. SWNT–ester–COOH (2, 2 mg) or SWNT–acyl–COOH (4, 4.5 mg) was reacted with EDC (180 mg), HOBt (126.8 mg) and PEI (10 kDa, 220 mg) using the same procedure as given above for 1.8 kDa PEI, except that purification by dialysis used a 12 000 to 14 000 MWCO membrane. SWNT–ester–COOH (2, 2 mg) or SWNT–acyl–COOH (4, 4.5 mg) was reacted with EDC (180 mg), HOBt (126.8 mg) and PEI (25 kDa, 550 mg) using the same procedure as given above for 1.8 kDa PEI, except that purification by dialysis was completed with a 25 000 MWCO membrane. The PEI-grafted SWNTs were lyophilized and used to prepare 1 mg ml–1 stocks. Ester-linked SWNT–PEI conjugates and acyl-linked SWNT–PEI conjugates are abbreviated as Sx (S series) and ACx (AC series), respectively, in which x shows the molecular weight (kDa) of polymer in the conjugate formulation.

2.3. Characterization methods

2.3.1. IR spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were used to confirm the modification of the SWNT surface and attachment of different groups.26 IR spectra were recorded in KBr discs with wavelength ranging from 4000 to 500 cm–1.

2.3.2. Thermogravimetric analysis

The degree of grafting of PEI onto the SWNT surface was determined by thermogravimetric analysis.27–29 Thermogravimetric analysis diagrams were obtained using the TGA 50 instrument (Shimadzu, Japan) by heating the sample at a rate of 10 °C min–1 to 800 °C in air.

2.3.3. Buffering capacity measurement

20 μl aqueous solutions of functionalized SWNTs (1 mg ml–1) were diluted to the final volume of 500 μl and then 0.05 M NaOH was added to adjust the pH values to 12. Changes of pH (12 to 2.5) for each sample were recorded upon titration by serial addition of 2.5 μl aliquots of 0.05 M HCl (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland) after each addition. The slope of the plot of pH versus amounts of proton concentration demonstrates the intrinsic buffering capacity of the various polycations.

2.3.4. DNA condensation analysis

SWNT derivatives were analyzed for their ability to condense pDNA by measuring the intercalation of ethidium bromide (EtBr) by fluorescence spectroscopy (Jasco FP-6200 spectrofluorometer, Tokyo, Japan) with excitation at 510 nm and emission at 590 nm. The fluorescence intensity of 1 ml of EtBr solution (400 ng ml–1 in HEPES buffered glucose (HBG)) containing pDNA (5 μg) was set to 100%. Aliquots (2.5 μl) of the SWNT derivative solution (1 mg ml–1) were added and the fluorescence intensity was determined when it reached a constant value. Condensation of DNA was calculated from the reduction in fluorescence.

2.3.5. Size and zeta potential of SWNT–PEI conjugates

The average size of SWNT–PEI/plasmid DNA polyplexes and their surface charges were measured in particle-free deionized water using a Malvern Zeta Sizer in automatic mode and DTS software (Malvern Instruments, UK). Because complete condensation of plasmid DNA was observed at C/P = 2 in all cases, this ratio was used for determination of both size and zeta potentials. After mixing 125 μl of a solution containing 10 μg of vector and 5 μg of plasmid DNA, the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 25 minutes. Then, 750 μl of deionized water was added and data were recorded. Each measurement is the mean of 30 instrument readings. Results are presented as mean ± SD for three independent measurements.

2.3.6. Imaging of SWNT–PEI conjugates by scanning electron microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to scan the surface topography and measure the nanotube diameters. SEM images were captured on a VEGA\TESCAN instrument under vacuum using a gold sputtering technique for sample preparation.

2.4. Biological tests

2.4.1. Cell culture

N2A murine neuroblastoma cells (ATCC CCL-131) were cultured in DMEM (1 g L–1 glucose, 100 μg mL–1 streptomycin, 100 units per mL penicillin and 2 mM glutamine) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Each well of 96-well plates was inoculated with 104 cells in a 100 μl DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, which were cultured for 24 hours before use. When N2A cells were used for both cytotoxicity and transfection experiments, the medium was removed and replaced with 100 μl of fresh medium with 10% FBS and cells were cultured overnight.

2.4.2. Preparation of polyplexes

Polyplexes were prepared for four different carrier-to-plasmid weight ratios (C/P) by mixing 200 ng of Renilla luciferase plasmid DNA or 400 ng of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) plasmid DNA30,31 with calculated weights of SWNT–PEI based on plasmid weights to form polyplexes with C/P weight ratios of 2, 4, 6 and 8. SWNT–PEI conjugates were diluted to a final volume of 10 μl of medium, mixed with an equal volume of medium containing DNA and incubated at room temperature for 25 minutes, and then 20 μl of preformed polyplexes were added into each well of a 96-well tray and incubated for 4 hours for cytotoxicity and transfection experiments.

2.4.3. Cytotoxicity assay

The toxicity of each vector was evaluated by treating N2A cells with 20 μl of polyplexes with different C/P ratios, four replicates each, for 4 hours under normal culture conditions. The medium was replaced with a fresh medium with 10% FBS and the cells were cultured for an additional 18 hours at 37 °C. Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay procedure.23 The medium was replaced with 100 μl of DMSO to dissolve formazan crystals. Cell viabilities were analyzed using a microplate reader (Tecan, Switzerland) at absorbance wavelengths of 590 cm–1 and 630 cm–1 as reference.

2.4.4. Transfection activity

Transfection efficiencies of SWNT–PEI derivatives were measured using the Promega Renilla Luciferase Assay kit and its protocol. N2A cells were treated with 20 μl of polyplexes prepared with Renilla luciferase plasmid DNA at different weight ratios (C/Ps), four replicates each, for 4 hours under normal culture conditions. The medium was replaced with a fresh medium with 10% FBS and the cells were cultured for an additional 18 hours at 37 °C. The cells were lysed and Renilla luciferase activity was recorded as relative light unit (RLU) using a luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany). The data were presented as RLU per number of cells.19

For transfection studies using EGFP, N2A cells were treated with 20 μl of polyplexes prepared with EGFP plasmid DNA at different weight ratios (C/Ps), four replicates each, for 4 hours under normal culture conditions. After replacement of medium with serum-supplemented fresh DMEM and incubation for 24 hours at 37 °C, fluorescence microscopy (Juli Smart Fluorescent Cell Analyzer, UK) was used to capture images of expressed EGFP protein within the cells. Previous studies on transfection efficiency of PEI have shown that the higher the C/P ratio of PEI, the higher both the cytotoxicity and transfection activity. PEI 25 kDa at C/P = 0.8 is reported as a standard control in many research articles as it shows reasonable transfection levels yet the lowest cytotoxicity. In this study, PEI 25 kDa at C/P = 0.8 was used as the control.32,33

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Instat software (version 3). Statistical significance was determined using the Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons test and P-values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant. Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis of PEI-grafted SWNTs

PEI was conjugated to SWNTs by amide bond formation with a terminal carboxylate group on two different linkers. In the first method, succinate linkers were attached by esterification to hydroxyl groups formed on the SWNTs (Fig. 2iA). In the second method, succinate linkers were attached directly to the SWNTs by Friedel–Crafts acylation reaction (Fig. 2iB). Attachment of PEI improved SWNT solubility in aqueous media and provided the positive charge on the SWNTs required for DNA condensation.

3.2. FTIR analysis

Infrared spectroscopy is commonly used to confirm the presence of different functional groups on a carbon nanotube.34,35 The FTIR spectra of amide-linked SWNT–PEI conjugates contained a peak at 1630 cm–1 confirming the formation of amide bonds while the characteristic peak related to the carboxyl group of functionalized SWNTs disappeared after amidation; methylene groups of the conjugates were observed at around 2820 and 2940 cm–1 while amine peaks appeared at 3430 cm–1 for all six products (Fig. 2i and ii). The introduction of hydroxyl groups into functionalized SWNTs was confirmed by peaks at 3432 cm–1 and 1050 cm–1 (Fig. 2iA). Addition of succinate linkers in the next step was confirmed by a peak at 1721 cm–1 (Fig. 2iB), which subsequently disappeared in all ester-linked SWNT–PEI conjugates due to amide bond formation (Fig. 2iC–E). In acyl-linked SWNT–PEI conjugates functionalized by the Friedel–Crafts reaction, the peaks at 1645 cm–1 and 3400 cm–1 correspond to the carbonyl and hydroxyl groups, respectively (Fig. 2iiA). Attachment of PEI in acyl-linked SWNT–PEI conjugates was confirmed by peaks for CH2 and NH2 stretching in the FTIR spectra (Fig. 2iiB–D).

3.3. Thermogravimetric analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out for both confirmation of SWNT content and determination of the percentage by weight of moieties grafted onto SWNTs for the SWNT–PEI conjugates with each linker. In each group, TGA was carried out for the vector that gave the highest transfection efficiency relative to that of the corresponding unmodified PEI, specifically the conjugates with 1.8 kDa PEI. The SWNT was thermally stable up to 500 °C; the residue that remained intact up to this temperature in each thermogram corresponded to the weight percent of SWNT in SWNT–PEI (Fig. 3). As previously reported,29 SWNT–COOH is more thermally stable than underivatized SWNT. Accordingly, the percentages of grafting onto SWNTs for SWNT–ester–PEI1.8 (S1.8) and SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8 (AC1.8) were 72% and 81%, corresponding to weight ratios of 1.35 μmol of ester–succinate–PEI moiety per 1 mg of S1.8 and 2.26 μmol of acyl–succinate–PEI moiety per 1 mg of AC1.8, respectively.

Fig. 3. Thermogravimetric analysis of A) pristine SWNT, B) SWNT–OH and the SWNT–PEI conjugates with the highest transfection efficiency for each type of linker, specifically C) SWNT–ester–PEI1.8 and D) SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8.

3.4. Buffering capacity of SWNT–PEI conjugates

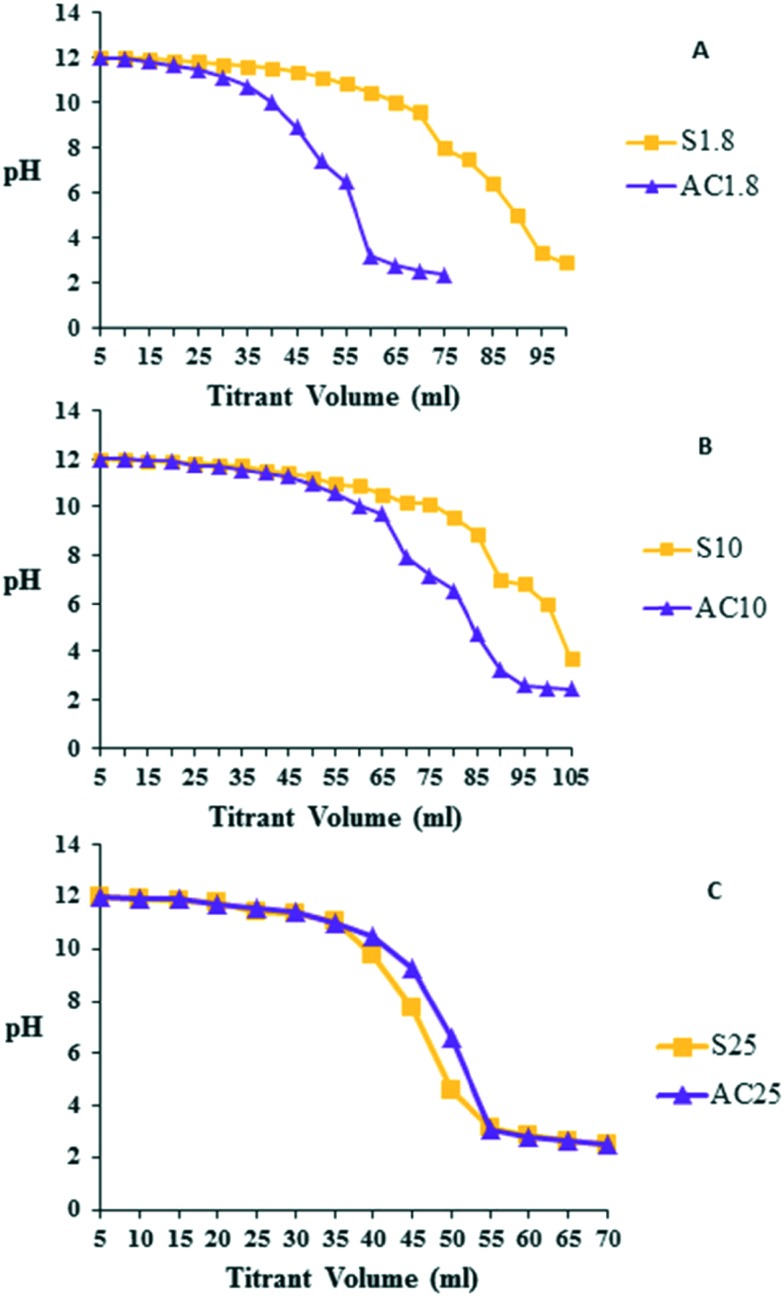

PEI contains many amine groups, particularly primary amines, which enable it to act as a buffer in the endosomal pH range. This buffering capacity is believed to enable endosomal escape and avoid degradation in lysosomes.36 The escape mechanism has been widely explored by various research groups and the ‘proton sponge effect’ is the most accepted mechanism.18,19 However, a recent study has shown that the endosomal pH remains unchanged after PEI internalization.37 To measure the buffering capacities of the SWNT–PEI conjugates, stocks (0.4 μg ml–1) were adjusted to pH 12 and titrated by adding 5 μl aliquots of 0.1 N HCl. The slopes of the titration diagrams were used to determine the buffering capacity of each conjugate Fig. 4(A–C). All SWNT–PEI conjugates exhibited reasonable buffering capacities at a pH range of 5–7, covering the whole pH range of the endosomal system, required for transfection activity. PEI contains many amine groups, particularly primary amines, which enables it to act as a buffer at the endosomal pH range. This facilitates the endosomal escape and consequently avoid the degradation by lysosomes.19,38

Fig. 4. Buffering capacity of SWNTs conjugated to A) 1.8 kDa PEI, B) 10 kDa PEI and C) 25 kDa PEI. Solutions of SWNT–PEI conjugates (0.4 mg ml–1) were prepared (squares: ester-linked; triangles: acyl-linked) and the pH was adjusted to 12. Titration of the solutions was carried out by adding 5 μl aliquots of 0.1 N HCl followed by reading the pH on a pH meter. The buffering capacity was estimated from the slope of the titration curve.

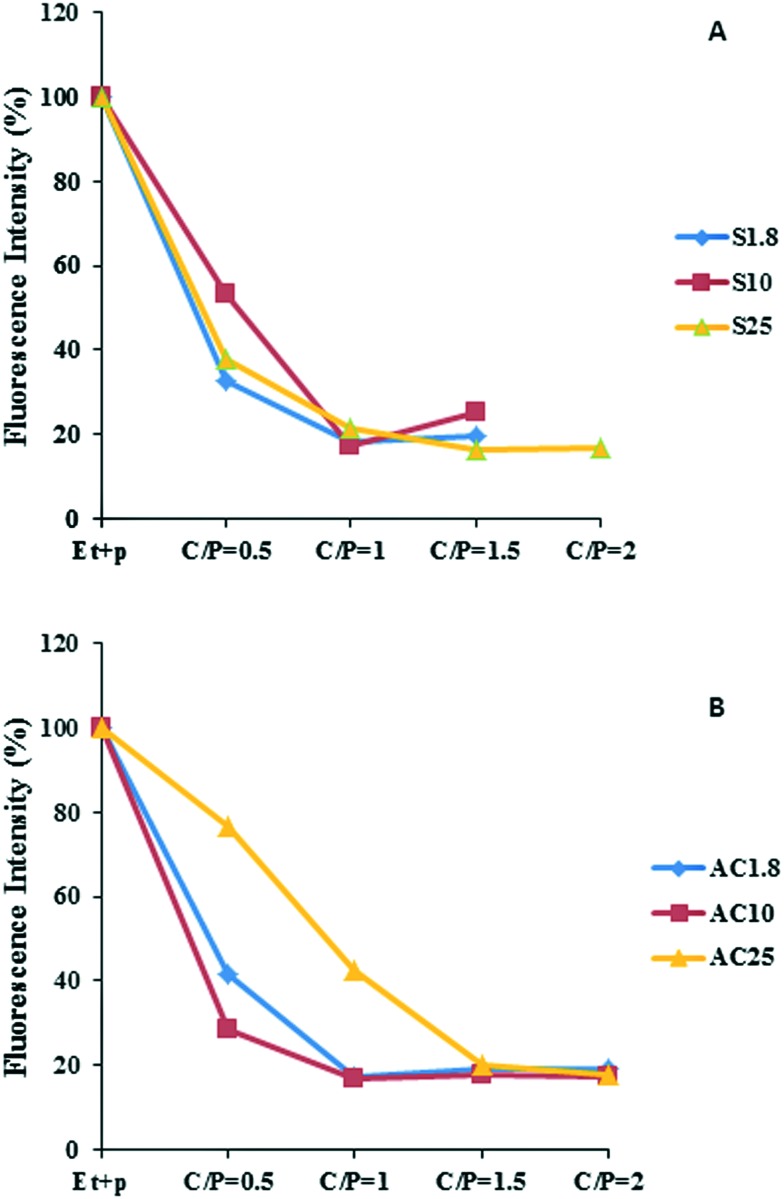

3.5. DNA condensation by SWNT–succinate–PEI conjugates

Ethidium bromide (EtBr) emits fluorescence at 590 nm upon intercalation in double stranded nucleic acids. When SWNT–PEI conjugates are added to plasmid DNA with bound EtBr in the HBG buffer, the DNA is condensed on the PEI and some of the intercalated EtBr dissociates from the DNA into the aqueous phase resulting in a measurable decrease in fluorescence intensity.23 Changing the structure of plasmid DNA from coil to a globular shape during condensation is another mechanism that can make the interaction of pDNA with EtBr difficult and thus decreases the fluorescence intensity. All six SWNT–PEI conjugates were capable of effective condensation of plasmid (Fig. 5A and B). For SWNT–ester–PEI1.8 (S1.8), SWNT–ester–PEI25 (S25) and SWNT–acyl–PEI10 (AC10), condensation was maximum at C/P = 0.5, while in the case of SWNT–ester–PEI10 (S10) and SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8 (AC1.8), maximum condensation occurred at C/P = 1.

Fig. 5. Ethidium bromide exclusion measurements of the relative condensation of plasmid DNA by A) SWNT–ester–PEI conjugates and B) SWNT–acyl–PEI conjugates. The fluorescence intensity of ethidium bromide fully intercalated into plasmid DNA (5 μg) was set at 100%. Addition of increments of SWNT–PEI conjugate preparations resulted in lowering of fluorescence intensity until a plateau was reached.

3.6. Size and zeta potential of SWNT–succinate–PEI conjugates

The size and surface charge of nanoparticles have a major impact on their transfection activity.39 The sizes of the polyplexes prepared with SWNT–PEI are presented in Fig. 6i. The size of SWNT–ester–PEI nanoparticles is in the range of 90–112 nm (Fig. 6iA) while SWNT–acyl–PEI nanoparticles have larger size in the range of 119–244 nm (Fig. 6iB). The zeta potentials of the polyplexes prepared with SWNT–PEI are presented in Fig. 6ii. All nanoparticles bear positive surface charges in the range of 18–32 mV (Fig. 6iiA and iiB). We suggest that for interpretation of the transfection results, the ratio of size/zeta potential should be considered for each pair of carriers consisting of PEI with a similar molecular weight. Based on the ratio of size/zeta potential calculated for each carrier according to the results presented in Fig. 6, the following trend was observed: AC1.8 > S1.8, AC10 > S10 and AC25 > S25. The same trend was observed for the transfection efficiency of each carrier group.

Fig. 6. i: Sizes of nanoparticles prepared with plasmid DNA (C/P = 2) and A) SWNT–ester–PEI conjugates or B) SWNT–acyl–PEI conjugates. ii: Zeta potentials of nanoparticles prepared with plasmid DNA (C/P = 2) and A) SWNT–ester–PEI conjugates or B) SWNT–acyl–PEI conjugates. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3).

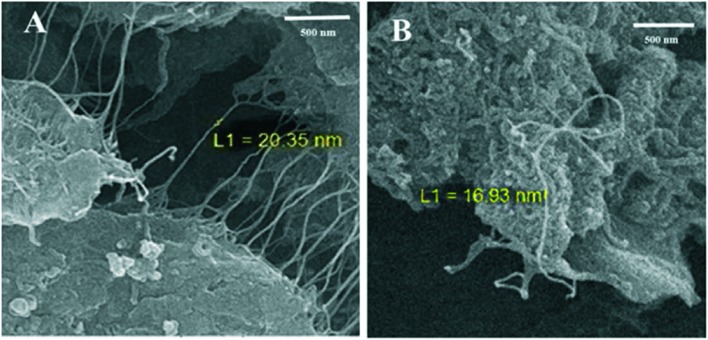

3.7. SEM imaging of SWNT–PEI conjugates

SEM was employed to study the surface topography and measure the diameters of the polyplexes prepared with SWNT–PEI conjugates (Fig. 7). The SEM micrographs clearly show that SWNTs were coated with PEI along the length of the SWNTs, thus their diameters increased from 1.4 nm to 16–20 nm. These topographic changes confirm the chemical functionalization of carbon nanotubes40,41 and indicate that linkage sites were formed along the lengths of the SWNTs, not only at proton-bearing sites at the ends of the SWNTs.

Fig. 7. SEM images of SWNT–PEI conjugates A) SWNT–ester–PEI1.8 (S1.8) and B) SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8 (AC1.8).

3.8. Cytotoxicity of polyplexes prepared with SWNT–PEI conjugates

Since the highest transfection activity for all SWNT–PEI conjugates was observed at C/P = 8 and below, cytotoxicity levels were evaluated within the same range of C/P ratios (2, 4, 6 and 8). None of the SWNT–PEI1.8 polyplexes exhibited significant cytotoxicity except SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8 (S1.8) at C/P = 6 (P < 0.05) for which around 87% of cells are viable (Fig. 8A). None of the SWNT–PEI10 polyplexes exhibited significant cytotoxicity (Fig. 8B) except SWNT–acyl–PEI10 (AC10) at C/P = 2 and 8 (P < 0.05), while SWNT–ester–PEI10 (S10) at C/P = 2 and 8 improved the viability (P < 0.001). None of the SWNT–PEI25 polyplexes exhibited significant cytotoxicity (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8C) except SWNT–acyl–PEI25 (AC25) at C/P = 4, SWNT–ester–PEI25 (S25) at C/P = 2 and 6, and SWNT–acyl–PEI25 (AC25) at C/P = 4 and 8. The control 25 kDa PEI exhibited significant cytotoxicity (P < 0.05) under all the conditions tested.

Fig. 8. MTT assay results for A) 1.8 kDa PEI, B) 10 kDa PEI and C) 25 kDa PEI.

3.9. Transfection activity of polyplexes prepared with SWNT–PEI conjugates

The largest increase in transfection efficiency resulting from conjugation of PEI to SWNTs was observed for coupling the smallest PEI used in the study (Fig. 9), 1.8 kDa PEI. Polyplexes prepared from free 1.8 kDa PEI resulted in very low levels of luciferase expression, but polyplexes prepared from 1.8 kDa PEI conjugated to SWNTs resulted in up to 190-fold higher luciferase expression compared with PEI 1.8 kDa for the SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8 (AC1.8) conjugate at C/P = 4 (P < 0.001) and over 4-fold higher luciferase expression than that of the free 25 kDa PEI control at C/P = 0.8 (Fig. 9A). The study also included an investigation of the effect of linker structure on transfection efficiency in the series of conjugates prepared with 1.8 kDa PEI. Transfection efficiency was the highest in polyplexes prepared with SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8 (AC1.8) conjugates for all C/P ratios studied. Polyplexes prepared with SWNT–ester–PEI1.8 conjugates resulted in increased luciferase expression for all C/P ratios studied, including 24-fold (P < 0.01) higher luciferase expression at C/P = 8 and marginal improvement in transfection efficiency compared to PEI 25 kDa at C/P = 0.8. The buffering capacity and its role in lysosomal escape do not explain the marked increase in transfection efficiency on conjugation of 1.8 kDa PEI to SWNTs.37 Increased luciferase expression at elevated C/P ratios was in accordance with other reports showing that excess free PEI (excess amount with respect to C/P ratio needed for complete condensation) plays a key role in improving the transfection efficiency.35

Fig. 9. Transfection efficiency of polyplexes prepared with plasmid DNA encoding luciferase and A) 1.8 kDa PEI, B) 10 kDa PEI and C) 25 kDa PEI at the indicated C/P values. S25 showed very low transfection levels that don't fit the scale of the diagram.

Polyplexes prepared with SWNT conjugates based on 10 kDa PEI showed a marginal or no improvement in transfection efficiency compared with polyplexes prepared with free 10 kDa PEI regardless of the linker or C/P ratio used (Fig. 9B). In each case, transfection efficiency was comparable with or less than that for the polyplexes prepared with the positive control 25 kDa PEI at C/P = 0.8. Plausible explanations include the reduced availability of surface amines of 10 kDa PEI when conjugated to SWNTs, as well as less total 10 kDa PEI when conjugated to the surface of SWNTs.

Polyplexes prepared with SWNTs conjugated to the largest PEI used in the study, 25 kDa PEI, exhibit low or no detectable transfection efficiency (Fig. 9C). The highest transfection efficiencies observed in the study were in polyplexes formed with free 25 kDa PEI with transfection efficiency increasing roughly in proportion to the C/P ratio.

3.10. Imaging of transfected enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) plasmid DNA

Enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was used as a reporter gene to compare the transfection efficiency of SWNT–PEI conjugates. Expression of EGFP plasmid DNA was detected as fluorescence images (Fig. 10), which confirmed the results obtained for transfection of Renilla luciferase plasmid DNA. The most effective SWNT–PEI conjugates were those prepared with 1.8 kDa PEI. Polyplexes prepared with both SWNT–ester–PEI1.8 (S1.8) and SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8 (AC1.8) (Fig. 10E and F) induced EGFP expression more efficiently than free 1.8 kDa PEI (Fig. 10A), and SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8 (AC1.8) was as efficient as the positive control, free 25 kDa PEI (Fig. 10B). However, polyplexes prepared with SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8 (AC1.8) (Fig. 10F) exhibited the largest enhancement in transfection efficiency, exceeding that of polyplexes prepared with free 25 kDa PEI (Fig. 10D).

Fig. 10. EGFP expression level images in N2A cells: A) PEI 1.8 kDa at C/P = 4, B) PEI 25 kDa at C/P = 0.8, C) PEI 1.8 kDa at C/P = 8, D) PEI 25 kDa at C/P = 4, E) SWNT–ester–PEI1.8, and F) SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8. Cells were treated with vector:pDNA (plasmid dose: 0.4 μg per well) complexes for 4 hours and images were taken after 24 hours of incubation at 37 °C.

4. Discussion

Two key characteristics of polyplexes that can affect uptake and gene delivery are surface charge and hydrodynamic size,42,43 which were evaluated using laser doppler velocimetry (LDV) and dynamic light scattering (DLS), respectively. For the SWNTs which conjugated to 1.8 kDa PEI, SWNT–ester–PEI1.8 and SWNT–acyl–PEI1.8, the size of polyplexes was 90 and 119.4 nm with zeta potentials of 20.8 and 22.6 eV, respectively (Fig. 6iiA and iiB). For the polyplexes prepared with SWNTs which conjugated to 10 kDa PEI, SWNT–acyl–PEI10 showed no improvement in transfection efficiency compared with free 10 kDa PEI, with a size of 244 nm and a zeta potential of 32.2 mV. However, SWNT–ester–PEI10 exhibited an approximately 10-fold lower transfection efficiency than free 10 kDa PEI, which can be attributed to its lower zeta potential (14 eV). SWNTs conjugated to 25 kDa PEI yielded polyplexes with both larger sizes (≥112 nm) and higher positive charges (≥27 eV). Polyplexes prepared with SWNT–acyl–PEI25 (AC25) gave transfection efficiencies approximately 10-fold higher than those of polyplexes prepared with SWNT–acyl–PEI10 (AC10), but about one quarter the transfection efficiency observed with polyplexes prepared from free 25 kDa PEI.

A major obstacle in the use of PEI as a transfection agent is that structural modifications which improve transfection efficiency also increase cytotoxicity. For example, PEIs with a higher molecular weight are more efficient transfection agents, but they are also more toxic.44 Various strategies to increase transfection efficiency without increasing cytotoxicity have been investigated. One such strategy is the preparation of higher molecular weight PEI aggregates using crosslinking agents. Introducing degradable linkers into aggregated PEIs was investigated as an approach to reduce toxicity; this is because these PEI aggregates should be degraded to smaller, less toxic forms after delivery of DNA to the inside of the target cells. The smaller PEIs are more easily eliminated via excretion pathways. Different degradable linkages such as ester, amide, imine, carbamate and ketals have been used.45 Amide bonds are more resistant to uncatalyzed hydrolysis than ester linkages, which may slow the degradation of amide-linked aggregates into less toxic subunits.46 This study compares the transfection efficiency and cytotoxicity of gene carriers based on PEI with a range of molecular weights conjugated via amide bond to SWNT which is linked to succinate linker through either ester bond (SWNT–ester–PEI) or acyl bond (SWNT–acyl–PEI). Comparing the cytotoxicities (Fig. 8) and transfection efficiencies (Fig. 9) of the two classes of linkers indicates that the acyl linker was the most effective, particularly with the lowest molecular weight PEI (i.e. PEI 1.8 kDa). The finding that SWNT–PEI conjugates based on PEI 1.8 kDa show higher transfection levels is consistent with our previously reported study.17 The same trend was observed for vectors based on low molecular PEI, bearing cleavable bonds.45 The absence of enhanced transfection efficiencies (Fig. 9) or reduced cytotoxicities (Fig. 8) of polyplexes formed with SWNT–ester–PEI is consistent with ester linkage stability under the prevailing experimental conditions. Attachment of PEI to multi-walled carbon nanotubes has been extensively studied with respect to cytotoxicity, transfection and gene silencing ability.47–51

It has been shown that the number of PEI molecules that can be grafted to a specific area on the surface of SWNTs depends on the PEI molecular weight,39 and this is consistent with steric blocking of carboxylate reaction sites. For branched PEI with a molecular weight of 1.8 kDa or lower, the number of PEI molecules that can be attached is greater with a lower molecular weight, whereas for those with molecular weights above 1.8 kDa, the number of PEI molecules attached is little changed.47 It has also been reported that grafting large molecules like polyethylene glycol (PEG) to PEI leads to a decrease in available amine groups due to a shielding effect.52 Similar results have been observed in this laboratory for non-covalent attachment of alkylated PEI to SWNT surfaces.17 For SWNTs conjugated to 1.8 kDa PEI, higher numbers of PEI molecules can be attached to the carbon nanotube wall, compensating for the smaller number of positively charged amines per molecule and shielding of some amine groups that are stereochemically rendered inaccessible by the carbon nanotube wall,17 so that the net effect was an improved transfection efficiency compared to free 1.8 kDa PEI. In the cases of SWNTs conjugated to 10 kDa PEI and particularly to 25 kDa PEI, the entire carbon nanotube wall was covered with PEI molecules (Fig. 9B and C), resulting in more shielding of primary amines by other PEI molecules, thereby reducing transfection efficiency relative to that of the free PEI.

5. Conclusions

Combining the excellent DNA transporting activity of PEI with the cell penetration ability of SWNTs was explored as a strategy for designing new non-viral vectors for gene delivery. Six vectors were synthesized by coupling PEIs with three different molecular weights to SWNTs through three different linkers with different levels of chemical stability. The lowest molecular weight PEI used (1.8 kDa) yielded conjugates with the greatest enhancement of transfection efficiency relative to that of the corresponding free PEI. It has previously been reported that PEI molecules with a molecular weight of 1.8 kDa and lower can be coupled to SWNTs in larger numbers than can higher molecular weight PEIs, for which the PEI/SWNT ratio is relatively constant. The inaccessibility of some NH2 groups in higher molecular weight PEIs conjugated to SWNTs may account for their lower enhancement of transfection efficiency relative to that of free PEI of the same molecular weight.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences and Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there are no financial or other conflicts of interest relevant to the subject of this article.

Acknowledgments

Assistance from the Iran Nanotechnology Initiative is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

†The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Iijima S. Nature. 1991;354:56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Peng X., Komatsu N., Bhattacharya S. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007;2:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J. J., Coleman K. S., Azamian B. R., Bagshaw C. B., Green M. L. Chem. – Eur. J. 2003;9:3732–3739. doi: 10.1002/chem.200304872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian K., Lee E. J., Weitz R. T., Burghard M., Kern K. Phys. Status Solidi A. 2008;205:633–646. [Google Scholar]

- Dyke C. A., Tour J. M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2004;10:812–817. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Hemraj-Benny T., Wong S. S. Adv. Mater. 2005;17:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Karousis N., Tagmatarchis N., Tasis D. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:5366–5397. doi: 10.1021/cr100018g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L., Zhang X., Lu Q., Fei Z., Dyson P. J. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1689–1698. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakare V. S., Prendergast D. A., Pastorin G. and Jain S., Carbon-Based Nanomaterials for Targeted Drug Delivery and Imaging, Targeted Drug Delivery: Concepts and Design, Springer, 2015, pp. 615–645. [Google Scholar]

- Yu B.-Z., Ma J.-F., Li W.-X. Nature Precedings. 2009:10101. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Zhang Y., Ma D. Colloids Surf., B. 2013;111:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyik C., Evran S., Timur S., Telefoncu A. Biotechnol. Prog. 2014;30:224–232. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M., Solati N., Ghasemi A. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery. 2015;12:1089–1105. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.1004309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Wen Y., Xu Q. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015;21:3191–3198. doi: 10.2174/1381612821666150531170219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashem Nia A., Eshghi H., Abnous K., Ramezani M. Nanomed. J. 2015;2:129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Yang K., Zhang Y. Acta Biotechnol. 2011;7:3070–3077. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnam B., Shier W. T., Nia A. H., Abnous K., Ramezani M. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;454:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussif O., Lezoualc'h F., Zanta M. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:7297–7301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehshahri A., Oskuee R. K., Shier W. T., Hatefi A., Ramezani M. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4187–4194. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey D., Inayathullah M., Lee A. S. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4647–4658. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geall A. J., Blagbrough I. S. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 2000;22:849–859. [Google Scholar]

- Parhiz H., Hashemi M., Hatefi A., Shier W. T., Farzad S. A., Ramezani M. J. Biomater. Appl. 2012;28:112–124. doi: 10.1177/0885328212440344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parhiz H., Hashemi M., Hatefi A., Shier W. T., Farzad S. A., Ramezani M. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013;60:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song P., Shen Y., Du B., Guo Z., Fang Z. Nanoscale. 2009;1:118–121. doi: 10.1039/b9nr00026g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek J.-B., Lyons C. B., Tan L.-S. J. Mater. Chem. 2004;14:2052–2056. [Google Scholar]

- Belin T., Epron F. Mater. Sci. Eng., B. 2005;119:105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Bahr J. L., Tour J. M. J. Mater. Chem. 2002;12:1952–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang I., Brinson B., Smalley R., Margrave J., Hauge R. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:1157–1161. [Google Scholar]

- Tian R., Wang X., Xu Y. J. Nanopart. Res. 2009;11:1201–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Tirlapur U. K., König K. Nature. 2002;418:290–291. doi: 10.1038/418290a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zizzi A., Minardi D., Ciavattini A. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2010;73:229–233. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ V., Elfberg H., Thoma C. Gene Ther. 2008;15:18–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Russ V., Wagner E. AAPS J. 2009;11:445–455. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9122-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan B., Cui D., Xu P. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:125101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/12/125101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan T., Fisher F., Ruoff R., Brinson L. Chem. Mater. 2005;17:1290–1295. [Google Scholar]

- Kunath K., von Harpe A., Fischer D. J. Controlled Release. 2003;89:113–125. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjaminsen R. V., Mattebjerg M. A., Henriksen J. R., Moghimi S. M., Andresen T. L. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:149–157. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi M., Parhiz B., Hatefi A., Ramezani M. Cancer Gene Ther. 2011;18:12–19. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2010.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabha S., Zhou W.-Z., Panyam J., Labhasetwar V. Int. J. Pharm. 2002;244:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson J. R., Bosaeus N., Kann N., Åkerman B., Nordén B. and Khalid W., Covalent functionalization of carbon nanotube forests grown in situ on a metal-silicon chip, SPIE Smart Structures and Materials+ Nondestructive Evaluation and Health Monitoring, International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2012, pp. 834411–834412. [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Pantarotto D., McCarthy D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4388–4396. doi: 10.1021/ja0441561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam D. Nat. Mater. 2006;5:439–451. doi: 10.1038/nmat1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan Y., Luo T., Peng C. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3025–3035. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D., Bieber T., Li Y., Elsässer H.-P., Kissel T. Pharm. Res. 1999;16:1273–1279. doi: 10.1023/a:1014861900478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jere D., Jiang H., Arote R. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery. 2009;6:827–834. doi: 10.1517/17425240903029183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloeckner J., Bruzzano S., Ogris M., Wagner E. Bioconjugate Chem. 2006;17:1339–1345. doi: 10.1021/bc060133v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon E. P., Crouse C. A., Barron A. R. ACS Nano. 2008;2:156–164. doi: 10.1021/nn7002713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foillard S., Zuber G., Doris E. Nanoscale. 2011;3:1461–1464. doi: 10.1039/c0nr01005g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes A., Amsharov N., Guo C. Small. 2010;6:2281–2291. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen M., Wang S. H., Shi X. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009;113:3150–3156. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wu D. C., Zhang W. D. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:4860–4863. [Google Scholar]

- Park M. R., Han K. O., Han I. K. J. Controlled Release. 2005;105:367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]