Abstract

Uptake of vitamin B12 is essential for many prokaryotes, but in most cases the membrane proteins involved are yet to be identified. We present the biochemical characterization and high-resolution crystal structure of BtuM, a predicted bacterial vitamin B12 uptake system. BtuM binds vitamin B12 in its base-off conformation, with a cysteine residue as axial ligand of the corrin cobalt ion. Spectroscopic analysis indicates that the unusual thiolate coordination allows for decyanation of vitamin B12. Chemical modification of the substrate is a property other characterized vitamin B12-transport proteins do not exhibit.

Uptake of vitamin B12 is essential for many prokaryotes, but in most cases the membrane proteins involved are yet to be identified. Here, the authors use X-ray crystallography and spectroscopy to characterize BtuM, a predicted bacterial substrate-modifying vitamin B12 transporter.

Introduction

Cobalamin (Cbl) is one of the most complex cofactors (Supplementary Figure 1a) known, and used by enzymes catalyzing for instance methyl-group transfer and ribonucleotide reduction reactions1,2. For example, in the methionine synthase MetH, the cofactor is used to transfer a methyl moiety onto l-homocysteine to produce l-methionine1,3. Many bacteria require Cbl for survival1,2,4,5, but only a small subset of prokaryotic species can produce this molecule de novo, via either an aerobic or anaerobic pathway4,5. Roughly two thirds of archaea and eubacteria are Cbl-auxotrophs that rely on uptake of either Cbl or its precursor cobinamide2,5,6 (Cbi, Fig. 1a, Supplementary Figure 1b). Dependence on uptake has probably evolved, because synthesis of Cbl involves roughly 30 different enzymes and is energetically costly. Gram-negative bacteria require the TonB-dependent transporter BtuB1 to transport Cbl across the outer membrane (Supplementary Figure 1c). For subsequent transport of vitamin B12 across the cytoplasmic membrane, the only characterized bacterial uptake system is the ABC transporter BtuCDF, which is predicted to be present in approximately 50% of Cbl-auxotrophic bacteria5,7. Many Cbl-auxotrophic Gram-negative bacteria do not encode BtuCDF, whereas they do contain BtuB. Metabolic reconstruction and chromosomal context analyses, e.g. co-localization with the gene for BtuB, have identified potential alternative inner membrane vitamin B12 transporters, one of which is BtuM5. BtuM homologues are small membrane proteins of ~22 kDa, and found predominantly in Gram-negative species, distributed mostly over α-, β-, and γ-proteobacteria (Supplementary Data 1).

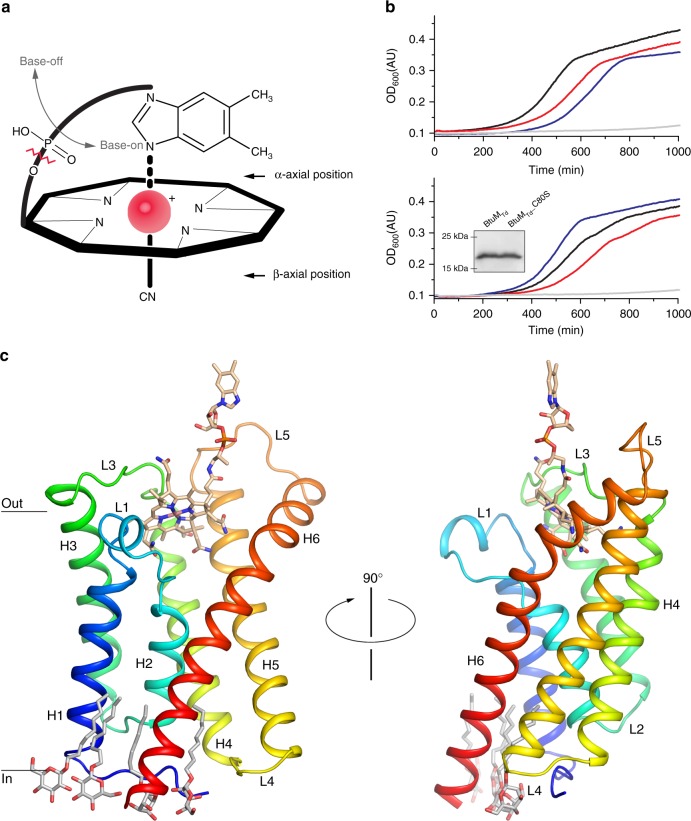

Fig. 1.

Function and structure of BtuMTd. a Schematic representation of cobalamin (Cbl) showing the corrinoid ring with the central cobalt ion (red). The ligand at the β-axial position is in this case a cyano-group, but differs in various Cbl variants (Supplementary Figure 1a, b). The ligand at the α-axial position (base-on conformation) is the 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole base, which is covalently linked to the corrinoid ring. When this coordination is lost, Cbl is termed base-off. Cbi lacks the 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole base (indicated by the zigzagged red line). b Growth assays with E. coli ΔFEC was conducted in the presence of 50 μg ml−1 l-methionine or 1 nM Cbl. Additional experiments in the presence of different Cbl concentration are shown in Supplementary Figure 2f and g. All growth curves are averages of nine experiments (three biological triplicates, each with three technical replicates). Top panel: cells containing the empty expression vector (pBAD24) in the presence of methionine (blue line) or Cbl (grey line) and cells expressing the BtuCDF system (black and red lines, respectively). Bottom panel: cells expressing BtuMTd (black and red lines) or mutant BtuMTd_C80S (blue and grey) in the presence of methionine and Cbl, respectively. The inset displays a western blot showing that the mutant is expressed to wild-type levels (the full-length western blot can be found in Supplementary Figure 2h). c The structure of BtuMTd in cartoon representation, coloured from blue (N terminus) to red (C terminus) and viewed from the membrane plane. α-helices (H1-6) and connecting loops (L1-5) are indicated. Cbl is shown in stick representation with carbon atoms coloured wheat, the oxygen and nitrogen atoms in red and blue, respectively, the cobalt ion in pink. Four n-nonyl-β-d-glucopyranoside detergent molecules are also shown in stick representation (carbons in light grey)

Here, we sought to characterize the predicted vitamin B12 transporter BtuM from Thiobacillus denitrificans (BtuMTd). We show that BtuMTd is involved in transport of Cbl in vivo and we solved its structure to 2 Å resolution. A cobalt–cysteine interaction allows for chemical modification of the substrate prior to translocation, which is a rare feature among uptake systems.

Results

BtuMTd supports vitamin B12-dependent growth

To test experimentally whether BtuMTd is a potential Cbl-transporter, we constructed an Escherichia coli triple knockout strain, E. coli ΔFEC, based on Cadieux et al.8. In this strain, the gene encoding the Cbl-independent methionine synthase, MetE9, is deleted. The metE deletion makes it impossible for E. coli ΔFEC to synthesize methionine, unless it can import Cbl8,9. In that case, l-methionine can be synthesized using the Cbl-dependent methionine synthase, MetH3,8. E. coli ΔFEC has additional deletions in btuF and btuC, encoding subunits of the endogenous Cbl-transporter BtuCDF7,8. Therefore, E. coli ΔFEC cannot import Cbl, prohibiting MetH-mediated l-methionine synthesis. Consequently, E. coli ΔFEC can grow only if l-methionine is present or if vitamin B12 import is restored by (heterologous) expression of a Cbl-transport system8. The phenotype of E. coli ΔFEC was confirmed in growth assays (Supplementary Figure 2a). Cells that are not expressing any Cbl-transporter did not exhibit substantial growth in methionine-free medium, whereas cells complemented with an expression plasmid for BtuCDF grew readily (Fig. 1b). Cells expressing BtuMTd had a similar growth phenotype, indicating that BtuMTd is a potential transporter for vitamin B12 (Fig. 1b).

Crystal structure of BtuMTd bound to vitamin B12

The BtuM family contains an invariably conserved cysteine residue (Supplementary Figure 3a). In BtuMTd, this cysteine is located at position 80, and mutation to serine abolishes the ability of the protein to complement the E. coli ΔFEC strain (Fig. 1b). To investigate the role of the cysteine, we solved a crystal structure at 2 Å resolution of BtuMTd in complex with Cbl. Data collection as well as refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. BtuMTd consists of six transmembrane helices with both termini located on the predicted cytosolic side (Fig. 1c). The amino acid sequences of BtuM proteins are not related to any other protein5 but, surprisingly, BtuMTd resembles the structure of S-components from energy-coupling factor (ECF)-type ABC transporters10 (Supplementary Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 1). In contrast to BtuM proteins, ECF-type ABC transporters are predominantly found in Gram-positive bacteria. They are multi-subunit complexes consisting of two peripheral ATPases and two transmembrane components (EcfT and S-component)10,11. EcfT and the ATPases together form the so-called ECF-module. S-components bind the transported substrate, and dynamically associate with the ECF-module to allow substrate translocation10,12–14. Intriguingly, no homologues of EcfT could be found in T. denitrificans. In addition, all ABC-type ATPases encoded by the organism are predicted to be part of classical ABC transporters, and not ECF transporters. Therefore, we conclude that the organism does not encode an ECF-module, and hypothesize that solitary BtuMTd may be responsible for Cbl uptake. This hypothesis is supported by the ability of BtuMTd to transport vitamin B12 when expressed heterologously in E. coli ΔFEC. Importantly, E.coli also does not encode an ECF-module11, hence BtuMTd cannot interact with a module from the host, and BtuMTd must be able to support Cbl uptake using a different mechanism than that of ECF transporters10,11. In a few cases, the biotin-specific S-component BioY15 has also been found in organisms lacking an ECF-module and was shown to mediate transport without the need for an ECF-module15. However, organisms encoding only BioY without an ECF-module are rare15, and in the large majority of organisms BioY is associated with an ECF-module11. In contrast, BtuM homologues (apart from one exception) are found exclusively in organisms lacking an ECF-module (Supplementary Data 1).

Table 1.

Data collection and phasing and refinement statistics

| Cbl-bound BtuMTd native | Cbl-bound BtuMTd anomalous | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| # Crystals/# datasets | 1/1 | 1/2 |

| Space group | P 31 2 1 | P 31 2 1 |

| Unit cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 87.54, 87.54, 97.91 | 86.60, 86.60, 97.51 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 41.13–2.01 (2.082–2.01)a | 43.30–2.50 (2.5896–2.5002)a |

| Rmerge (%) | 5.8 (>100)a | 10.8 (>100)a |

| cc1/2 | 100.0 (14.1)a | 99.9 (50.8)a |

| I/σI | 16.24 (0.23)a | 18.23 (1.53)a |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.8)a | 93.82 (64.7)a |

| Redundancy | 10.5 (9.7)a | 18.8 (11.0)a |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 41.13–2.01 | 43.30–2.50 |

| No. of reflections | 28,953 | 14,144 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.2121/0.2338 | 0.2492/0.2854 |

| Number of non-hydrogen atoms | 1870 | 1536 |

| Protein | 1640 | 1359 |

| Ligands | 208 | 177 |

| Water | 22 | 0 |

| B-factors | ||

| Protein | 89.0 | 67.2 |

| Cobalamin | 65.4 | 69.3 |

| PEG | 106.2 | — |

| Detergent | 107.1 | — |

| Water | 69.2 | — |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.81 | 1.916 |

aValues in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell

Further experiments, for instance using purified protein reconstituted in proteoliposomes, are required to test whether BtuMTd also catalyses transport in vitro without any additional component involved. However, the in vivo assay gives a very strong indication that BtuMTd is a transporter itself, as the protein was expressed in a heterologous host that does not contain any ECF-module or S-component. Similar in vivo experiments have been used extensively in the past to identify other transporters (for instance ref.16) and have the advantage over in vitro assays that physiologically relevant conditions are used.

BtuMTd binds cobalamin using cysteine ligation

Close to the predicted periplasmic surface of BtuMTd, we found well-defined electron density (Supplementary Figure 5) representing a bound Cbl molecule. The binding mode of Cbl in the crystal structure (Fig. 2a) is striking for two reasons. First, the essential Cys80 is the α-axial ligand of the cobalt ion. To our knowledge, cobalt coordination by cysteine has not been observed in any other Cbl-binding protein of known structure. Binding of cysteine to cobalt in a corrinoid has been hypothesized for the mercury methylating enzyme HgcA17 and observed in a synthetic cyclo-decapeptide, but in the latter case the residue replaced the β-ligand18.

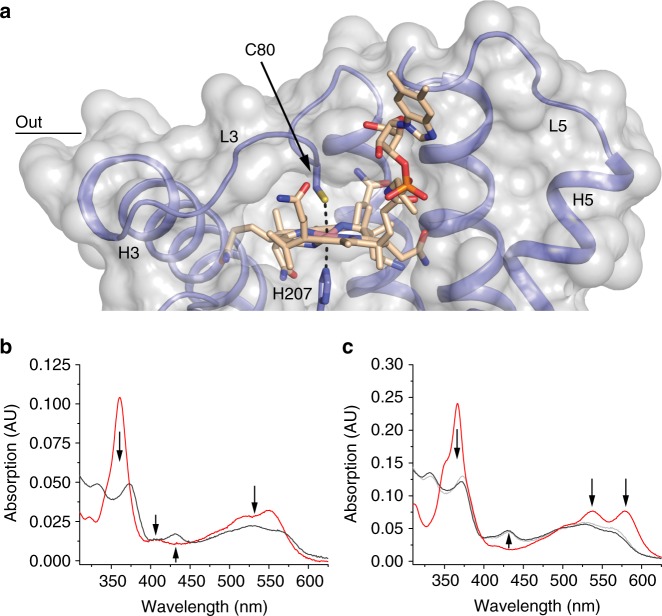

Fig. 2.

Binding of vitamin B12 by BtuMTd. a Transparent surface representation (light grey) of the binding pocket of BtuMTd with bound Cbl. The protein backbone is shown in blue. The Co-ion is coordinated by Cys80 located in L3 (Co to sulphur distance 2.7 Å) and His207 (Co to nitrogen distance 2.4 Å) from a neighbouring symmetry mate (Supplementary Figure 6). A complete description of the interactions of BtuMTd with its substrate can be found in Supplementary Figure 12. b The spectrum of BtuMTd_cHis8-bound Cbl (4.3 μM, black line) compared to unbound cyano-Cbl (2.4 μM, red line). The regions of the spectrum with major changes are indicated with arrows. c Same as b but with Cbi bound to the protein (9.2 μM black line), compared to unbound dicyano-Cbi (9 μM, red line). The regions of the spectrum with major changes are indicated with arrows. For comparison, a scaled spectrum of Cbl bound to BtuMTd (light grey line) from b is included, showing that the spectrum of both substrates bound to the protein is virtually the same, indicating the same binding mode

Second, Cbl is bound to BtuMTd in the base-off conformation in which the 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole moiety does not bind to the cobalt ion (Fig. 2a). In contrast, at physiological pH the conformation of free Cbl in aqueous solution is base-on with the 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole moiety coordinated to the cobalt ion in the α-axial position1 (Fig. 1a). The base-off conformation has been found only in a subset of Cbl-containing enzymes, but not in Cbl-binding proteins without enzymatic activity1, such as the periplasmic substrate-binding protein BtuF19, the outer membrane transporter BtuB20, and human Cbl-carriers intrinsic factor21, haptocorrin22 and transcobalamin23. Enzymes that bind Cbl with the base-off conformation usually use a histidine residue as the α-axial ligand. In this way, the reactivity of the cobalt at the β-axial position is altered, allowing among others a variety of methyl-group transfer reactions1. Therefore, the base-off binding mode by BtuMTd could indicate that the protein may exhibit enzymatic activity.

BtuMTd catalyses decyanation of vitamin B12

Indeed, the structure of BtuMTd suggests that the protein can catalyse chemical modification of the substrate. We co-crystallized BtuMTd with cyano-Cbl, which contains a cyano-group as the β-ligand1,4. Cyano-Cbl is the most stable form of vitamin B124 but, despite the tight binding of the β-ligand, in the crystal structure the cyano-group is absent indicating protein-mediated decyanation. Consistent with decyanation and the presence of a cysteine ligand in BtuMTd, the absorbance spectrum of Cbl-bound BtuMTd showed pronounced differences compared to that of free Cbl18,24 (Fig. 2b). The characteristic absorption peak at 361 nm of Cbl is absent and two peaks with lower absorption appear around 330 and 370 nm. The absorption between 500 and 580 nm is lower than in free Cbl, and a new peak at 430 nm is present.

In place of the cyano-group, the imidazole group of His207 from a neighbouring BtuMTd molecule in the crystal is located at the β-axial position. His207 is the last histidine residue of the His8 affinity-tag (His-tag) engineered at the C terminus of the protein (Supplementary Figure 6). Because crystal contacts may be non-physiological and the His-tag is a non-natural addition to the protein, we performed control experiments to exclude the possibility that decyanation is an artefact. First, we showed by mass spectrometry (MS) that the loss of the cyanide does not require crystal formation (Supplementary Figure 7a). Second, we showed that decyanation also occurred by BtuMTd with a C-terminal Glu-Pro-Glu-Ala (EPEA)-tag instead of a His-tag (Supplementary Figure 7b). Notably, the EPEA-tagged protein was active in the growth assay and also removal of the His-tag did not affect activity (Supplementary Figure 2b, c). Finally, binding of Cbl to BtuMTd with His-tag or EPEA-tag was accompanied by the same changes in absorption spectrum (Figs. 2b, 3b). Therefore, we conclude that decyanation takes place regardless of crystal formation or presence of a His-tag.

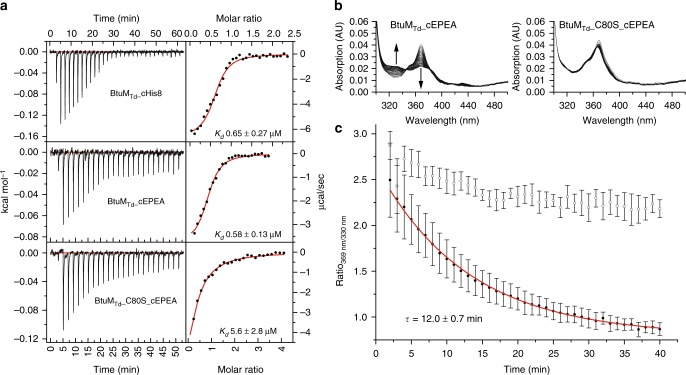

Fig. 3.

Cobinamide (Cbi) binding to BtuMTd and BtuMTd-catalysed decyanation. a Representative ITC-measurements of differently tagged BtuMTd constructs. BtuMTd with a C-terminal His-tag binds Cbi with a Kd value of 0.65 ± 0.27 μM (top). EPEA-tagged BtuMTd binds Cbi with essentially the same affinity of Kd 0.58 ± 0.13 μM (middle). For the EPEA-tagged mutant version BtuMTd_C80S Kd = 5.6 ± 2.8 μM (bottom). All ITC experiments were performed as technical triplicates, error is s.d. b Decyanation of Cbi catalysed by EPEA-tagged BtuMTd. Upon addition of an excess of BtuMTd to Cbi, the substrate is slowly decyanated, which can be followed spectroscopically (left) with the main spectral changes indicated by the arrows. The mutant BtuMTd_C80S, did not catalyse decyanation (right). c Quantification (error bars are s.d. of technical triplicates) of decyanation reveals that the process is slow. The ratio of the absorption at 369 nm over 330 nm of BtuMTd (black dots) was plotted as function of time. A mono-exponential decay function was fitted to the data (red line) to extract τ = 12 ± 0.7 min (s.d. of technical triplicates), which is comparable to the decyanation rate of the His-tagged protein and the process follows pseudo-first order kinetics (Supplementary Figure 8b, c). The ratio of absorption obtained with the cysteine mutant (open dots), which does not catalyse decyanation, is shown for comparison

Kinetics of the BtuMTd catalysed decyanation reaction

To study the kinetics of BtuMTd-catalysed decyanation we used cobinamide (Cbi) instead of Cbl as substrate. Because Cbi does not contain the 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole moiety (Fig. 1a), it mimics the base-off conformation of cobalamin, which makes the compound suitable to study decyanation without interference from the slow conversion25 of base-on to base-off Cbl. The absorption spectra of Cbl-bound and Cbi-bound BtuMTd are almost identical (Fig. 2c), indicating identical coordination of the cobalt ion of Cbi at the α-axial and β-axial positions. MS analysis showed that binding of Cbi to BtuMTd also results in decyanation (Supplementary Figure 8a). To probe Cbi binding by BtuMTd, we used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), which revealed dissociation constants for the His-tagged and EPEA-tagged protein of 0.65 ± 0.27 and 0.58 ± 0.13 μM (s.d. of the mean of technical triplicates), respectively (Fig. 3a). It is noteworthy that we were unable to assay for Cbl-binding by ITC. We speculate that the conversion from base-on to base-off Cbl is so slow25 that it may prevent detection of Cbl-binding by ITC. Additionally, the absence of the membrane environment also appears to preclude Cbl binding to purified BtuMTd, as binding was observed only when the substrate was added before solubilisation (Fig. 2b, c, Supplementary Figure 9).

Because binding of cyanide to cobinamide causes a decrease in absorbance at 330 nm and an increase at 369 nm24, we expected the opposite spectral changes upon decyanation. Addition of excess of apo-BtuMTd (Supplementary Figure 10a and b) to a solution of Cbi indeed revealed time-dependent changes in absorbance consistent with a decyanation reaction (Fig. 3b, c). Decyanation occurred with an apparent time constant of τ = 12 ± 0.7 min (s.d. from technical triplicates, Fig. 3c), which is comparable to the rate observed in the human decyanating enzyme CblC25,26. We also tested Cbi binding and decyanation using mutant proteins C80A and C80S. While these mutants were unable to bind Cbl, they remained capable of binding Cbi as demonstrated by co-purification of the molecule with the protein (Supplementary Figure 10c, d). We measured the affinity of BtuMTd_C80S to Cbi with ITC and found a dissociation constant of 5.6 ± 2.8 μM (s.d. of the mean of technical triplicates), which is an order of magnitude weaker than the wild-type (WT) protein. The absorbance spectra of Cbi bound to the mutant proteins showed the characteristic features for cyano-Cbi, indicating that decyanation was abolished (Supplementary Figure 10c, d). Consistently, the decyanation assay with BtuMTd_C80S did not reveal the slow spectral changes observed for the WT protein (Fig. 3b, c). These results show that Cys80 is required for decyanation of Cbi and that binding and modification of the substrate are separate events: fast binding (detected by ITC) is followed by slow modification. The lack of detectable binding of Cbl to BtuMTd_C80S (measured by lack of co-purification, Supplementary Figure 10c, d) may indicate that the cysteine is also required for base-on to base-off conversion, and that the base-on conformer binds with too low affinity for detection by co-purification. To understand BtuMTd-catalysed decyanation of Cbl and Cbi in more detail, we mutated conserved amino acids H28, D67, Y85, and R153 located in the binding pocket (Supplementary Figure 3b). Mutant D67A could not be purified, and was not analysed further. Cbl-bound mutants H28A, Y85L, and R153A displayed the same spectral properties as the WT protein (Supplementary Figure 11a), and MS analysis showed that the binding of Cbl was accompanied by decyanation, indicating that the conserved residues are not essential for the reaction (Supplementary Figure 11b–d). Finally, to exclude that BtuMTd is merely a decyanating enzyme, and that the potential reaction product hydroxyl-Cbl is subsequently transported by another protein, we show that BtuMTd also mediates uptake of hydroxyl-Cbl in the growth assay (Supplementary Figure 2d, e).

Discussion

We showed in vivo that BtuMTd is a vitamin B12 transporter, which is consistent with the predictions based on bioinformatics analysis5. Our work sheds light on the diversity of transport systems used for the uptake of vitamin B12. The outer membrane transporter BtuB is a TonB-dependent active transporter, which uses a different mechanism of transport than inner membrane proteins1,20. The well-studied inner membrane type II ABC transporter BtuCDF uses hydrolysis of ATP to pump Cbl into the cell like the ECF-transporter, ECF-CbrT27. Both systems require a substrate-binding protein and are multiprotein complexes7,8,27,28. BtuMTd on the other hand, must operate by a different mechanism because the protein lacks accessory components and the expected ATPase motifs of ABC transporters10. BtuMTd structurally resembles the S-components of ECF transporters. In ECF transporters, the S-components bind the transported substrate with high affinity and then associate with an ECF-module for energizing transport. During the transport cycle, the S-components rotate (topple over) in the membrane to bring the substrate from the outside to the cytoplasm. We hypothesize that BtuMTd mediates the translocation of Cbl through the membrane by a similar toppling mechanism. Because BtuMTd does not require an ECF-module, the transport mode may be facilitated diffusion along the concentration gradient of the substrate. In T. denitrificans and most other BtuM hosts, the BtuMTd gene co-localizes with btuR, which encodes for the cobalamin adenosyltransferase BtuR. This enzyme catalyses the synthesis of 5′-deoxyadenosyl-cobalamin and would offer a mechanism of metabolic trapping, similar to what has been proposed for other vitamin transporters in bacteria29.

Our work provides experimental evidence for a binding mode of Cbl, in which cysteine ligation and the base-off conformation are linked. This binding mode leads to decyanation of cyano-Cbl, for which we propose a reductive decyanation mechanism, which depends on Cys8017,18 (Supplementary Figure 8d). The proposed decyanation mechanism differs from the mechanism used by CblC, where a flavin acts as reducing agent. In CblC, the flavin donates two electrons resulting in the reductive decyanation (CN−) and the reduction of the Co-ion25,26. For BtuMTd, cysteine-catalysed reductive decyanation would only result in the release of CN−, but not in the reduction of the Co-ion.

Finally, BtuMTd likely combines two functions: transport of the substrate into the bacterial cell, and chemical modification of the substrate. Such combined functionality rarely occurs in transporters, and has been observed only in phosphotransferase systems30. However, in that case the modification (phosphorylation) takes place on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane30, whereas BtuMTd appears to modify on the periplasmic side of the membrane. Internalisation of decyanated vitamin B12 may be relevant because environmental cyano-Cbl exists26. A combination of decyanation and transport activity would make cyano-Cbl directly accessible for conversion into physiological forms, for example, by BtuR.

Methods

Bioinformatic identification of BtuM homologues and ECF-modules

The amino acid sequence of BtuMTd was used as a search query using the iterative jackHMMer algorithm (default settings) with the reference proteome database31 until the search converged leading to 131 hits. Within the genomes of the identified 131 organisms, we screened for the presence of an ECF-module using the pHMMer algorithm (default settings)31 with the amino acid sequence of the transmembrane component (ECF-T) from Lactobacillus delbrueckii14 as a search query. Additionally, we used the SEED viewer (http://pseed.theseed.org) to verify the absence of any ECF-transporter in a subset of organisms (46 present in the SEED database) and also used this tool to find all ABC transporters in T. denitrificans to verify that none of these are an ECF-transporter.

Molecular methods

For expression in E. coli MC106132 a codon optimized version (Invitrogen) of btuM (Tbd_2719) from Thiobacillus denitrificans ATCC25259 with a C-terminal eight histidine affinity-tag or EPEA-tag was used and introduced into pBAD2433 with NcoI and HindIII restriction sites. A single glycine (Gly2) was introduced to be in-frame with the start-codon of the NcoI restriction site. Single amino acid substitutions and removal of the affinity tag were conducted using site-directed mutagenesis. The complementation plasmid for expression of BtuC and BtuF was constructed using Gibson Assembly following the standard procedure (NEB). All constructs were checked for correct sequences by DNA sequencing. All primers are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Construction of the ΔFEC strain

E. coli ΔFEC, was constructed by P1-mediated generalized transduction27,34,35. In short: E. coli JW0154 (ΔbtuF::KmR) was used as the basis for construction of E. coli ΔFEC. The kanamycin resistance cassette was removed using the FLP-recombinase36. The metE::KmR locus from E. coli JW3805 and the ΔbtuC::KmR locus of E. coli JW1701 was introduced34,35, resulting in E. coli ΔFEC (ΔbtuF, ΔmetE, ΔbtuC::KmR). Colony PCRs based on three primer pairs27 were used to verify KmR-insertions, FLP-recombinase-mediated removal of KmR-markers and absence of genomic duplications (Supplementary Figure 13).

Growth assays

The strains carrying various expression vectors were grown overnight at 37 °C on LB-agar plates supplemented with 25 μg ml−1 kanamycin and 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin. M9 minimal medium (47.7 mM Na2HPO4 × 12H2O, 17.2 mM KH2PO4, 18.7 mM NH4Cl, 8.6 mM NaCl) was supplemented with 0.4% glycerol, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 100 μg ml−1 l-arginine, 25 μg ml−1 kanamycin and 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin. A single colony was picked and used to inoculate an M9-medium pre-culture supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 l-methionine (Sigma-Aldrich). The pre-culture was grown ~24 h at 37 °C, shaking in tubes with gas-permeable lids (Cellstar), and then used to inoculate the assay medium in a 1:500 ratio. The assay medium was supplemented with 0.00001% l-arabinose (Sigma-Aldrich) and either 50 μg ml−1 l-methionine, 0.01 nM, 1 nM and 5 nM cyano-cobalamin (Acros Organics), or 0.1 nM hydroxy-cobalamin (Sigma-Aldrich). Overall, 200 μl medium was added per well of a sterile 96 well plate (Cellstar). Plates were sealed with a sterile and gas-permeable foil (BreatheEasy, Diversified Biotech). The cultures were grown for 1000 min (1250 min for Cbi) in a BioTek Power Wave 340 plate reader at 37 °C, shaking. The OD600 was measured every 5 min at 600 nm. All experiments were conducted as technical triplicates from biological triplicate. The displayed growth curves are the averages of all nine curves.

Western blotting

Cells grown in LB-medium were broken in 50 mM K-Pi pH 7.5 supplemented with 10% glycerol, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and DNaseI with glass beads in a tissue lyser at 50 hertz. The lysate was centrifuged for 10 min at 20,000×g and 4 °C and the supernatant was used for further analysis. The samples analysed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by semi-dry western blotting. The primary antibody was mouse anti-Tetra·His Antibody, BSA-free from Qiagen (Cat.No. 34670) and the secondary antibody was anti-mouse IgG (whole molecule)-alkaline phosphatase conjugate antibody from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat.No. A1902-1ML). The dilutions were 1:2000 and 1:10,000, respectively. The full-length blot from Fig. 1 is included (Supplementary Figure 2h)

Overexpression and crude membrane vesicle preparation

All BtuMTd variants were overexpressed in E. coli MC1061. Overnight pre-cultures in LB-medium supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin were diluted in a 1:100 ratio and allowed to grow at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.6–0.8. Expression was induced by addition of 0.05% l-arabinose for 3 h. Cells were harvested, washed with 50 mM K-Pi pH 7.5, and broken with a Constant Systems cell disruptor at 25 kpsi in 50 mM K-Pi pH 7.5 supplemented with 200 μM PMSF, 1 mM MgSO4 and DNaseI. Cell debris were removed by centrifugation for 30 min with 25,805×g and 4 °C. The supernatant was centrifuged for 2.5 h at 158,420×g (average) and 4 °C to collect crude membrane vesicles (CMVs). The CMV pellet was homogenized in 50 mM K-Pi pH 7.5 and used for purification.

Purification of BtuMTd for crystallisation

His-tagged BtuM for crystallisation was solubilised in buffer A (50 mM HEPES/NaOH pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 0.05 mM cyano-Cbl, 1% n-dodecyl-β-maltoside (DDM) and 15 mM imidazole/HCl pH 8.5) for 45 min at 4 °C with gentle movement. Unsolubilized material was removed by centrifugation for 35 min at 219,373×g (average) and 4 °C. The supernatant was decanted into a poly-prep column (BioRad) containing 0.5 ml bed volume superflow Ni2+-NTA sepharose (GE healthcare) equilibrated with 20 column volumes (CV) buffer A containing additionally 3 mM dithiotreitol (DTT) and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C with gentle movement. Unbound protein was allowed to flow through and the column was washed twice with ten CV buffer A supplemented with 3 mM DTT and 0.35% n-nonyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (NG) and 60 mM or 90 mM imidazole/HCl pH 8.5. Bound protein was eluted from the column in four fractions of 0.5 ml (first)—0.7 ml (others) with buffer A supplemented with 3 mM DTT 0.35% NG and 350 mM imidazole/HCl pH 8.5. The sample was centrifuged for 5 min at 20,000×g and 4 °C to remove aggregates, and then loaded on a SD200 10/300 Increase SEC column (GE healthcare), which was equilibrated with 30 ml buffer B (50 mM HEPES/NaOH pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 0.005 mM cyano-Cbl and 0.35% NG) and eluted in the same buffer while monitoring absorption at 280 and 361 nm.

Purification of His-tagged BtuMTd

Purification of His-tagged protein for biochemical analyses was essentially performed as described above with the following adaptations. HEPES was replaced with 50 mM K-Pi pH 7 or 7.5 (for ITC and spectral analyses, respectively), NG was replaced with 0.04% DDM, and 100 mM NaCl was used throughout. For purification of the apo protein, substrate was omitted from all buffers. For spectral analyses of substrate-bound proteins, substrate was omitted from buffer B.

Purification of EPEA-tagged BtuMTd

EPEA-tagged protein was purified as described above with the following adaptations. CaptureSelectTM C-tagXL Affnity Matrix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used. DTT and imidazole were omitted in all steps and 50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5 was used instead of K-Pi. The column was washed once with 10 CV buffer supplemented with 500 mM MgCl2. Elution was done in four fractions of 0.5 (first) ml—0.8 ml (others) in buffer containing 2 M MgCl2.

Crystallisation and phasing and structure determination

BtuMTd purified for crystallisation was concentrated to between 1.1 and 1.6 mg ml−1 with a 10,000 kDa cut-off Vivaspin concentrator (Sartorius) at 4000×g at 2 °C. The initial screening was done using a Mosquito robot (TTP Labtech), and a hit was found after 1 month in the H1 condition (50 mM Tris pH 8.5, 28% (v/v) PEG400) of the MemGold2 screen (Molecular Dimensions) at 4 °C. Larger and better diffracting pyramid-shaped crystals were obtained at 8 °C after 3 to 4 weeks in a crystallization buffer containing 25 mM Tris pH 8.5 and 25 to 30% (v/v) PEG400, 50 mM Tris pH 8.5 and 27 to 30% (v/v) PEG400 or 75 mM Tris pH 8.5 and 29 to 30% (v/v) PEG400, using the sitting drop vapour diffusion method (in MRC Maxi 48-well plate) and a 1:1 mixing ratio (2 μl final drop volume) of mother liquor and protein solution. Phases were obtained from crystals that were soaked for 1 min with 100 mM Tb-Xo437 (Molecular Dimensions) mother liquor solution (0.5 μl added directly to the drop). Diffraction data of the native crystals were collected at the Swiss Light Source (SLS) at PXI (X06SA) beamline (λ = 1.000 Å, T = 100 K) and two anomalous diffraction datasets were collected at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) at beamline ID23-1 (λ = 1.400 Å and 1.476 Å, T = 100 K). Data were processed with XDS38 and the two datasets containing anomalous information were merged and subsequently used to solve the structure with ShelX39. Autobuild40 was used to obtain a starting model, which was refined further with Phenix refine41 with manual adjustments done in Coot42. The model was used as an input to solve the phase problem for the native dataset, which was carried out with Phaser-MR43. The model of the native data was refined iteratively with Phenix refine41 and manual adjustments were done in Coot42. The Ramachandran statistics for the final model are 99.47% for favoured regions, 0.53% for allowed regions and 0.00% for outliers. A stereo view of 2Fo – Fc electron density of the entire structure including the backbone trace molecule, the binding pocket and the Cbl-ligand is provided in Supplementary Figure 5a–c, respectively. All structural figures were prepared with an open-source version of pymol (https://sourceforge.net/projects/pymol/).

UV–Vis assay to determine decyanation of vitamin B12

All measurements were carried out in a Cary100Bio spectrophotometer (Varian) at room temperature and baseline corrected for buffer B in a quartz cuvette. To monitor the binding of dicyano-Cbi or cyano-Cbl by BtuMTd over time, every minute a spectrum was recorded between 260 and 640 nm for 40 min (Cbi, n = 3) or every 20 min for 12 h (Cbl, n = 1) at room temperature. For this measurement, a molar protein to substrate ratio of 5:1 (Cbi) or 1:1 (Cbl) was used. To obtain the apparent time constant, τ, the absorbance ratio of 369/330 nm was plotted against the time and fitted with a single exponential decay function in Origin 8. Decyanation assays with Cbi were conducted as technical triplicates and errors are standard deviations of the averaged ratios (if not specified otherwise).

ITC measurement with Cbi

Binding of dicyano-Cbi to purified BtuMTd was measured on a microcal200 ITC (GE healthcare) in high feedback mode. The cell temperature was set to 25 °C with a reference power of 9.5 μcal s−1. During the measurement, the sample was stirred at 750 rpm and a 15-fold excess (WT) or 32.5-fold excess (C80S) of Cbi in the syringe was used over the protein concentration in the cell. The data was analysed in Origin and experiments were done as technical triplicates (n = 3). The obtained dissociation constants were averaged and the error is the standard deviation of the replicates.

Mass spectrometry

BtuMTd variants and mutant proteins were purified as described above. BtuMTd proteins were diluted in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio with 0.1% formic acid and 5 μl were injected into an Ultimate 3000-UPLC system (Dionex), connected to a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and separated on a 2.1 mm × 50 mm Acquity UPLC BEHC18, 1.7 μm (Waters). Solvent A was H2O with 0.1% formic acid and solvent B was acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. The following mobile phase gradient was delivered at a flow rate of 0.6 ml min−1 starting with a mixture of 60% solvent B for 1 min. Solvent B was increased to 90% over 5 min with a linear gradient and kept at this concentration for 5 min. Solvent B was reduced to 60% in 0.1 min and kept for 3.9 min resulting in a total elution time of 15 min. The column temperature was kept constant at 40 °C. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive mode. Full scan MS spectra were acquired for 10 min from m/z 1000 to 2000 at a target value of 1 × 106 and a max IT of 500 ms with a resolution of 140,000 at m/z 200. Scans were averaged using Xcalibur 4.0.27.42 Qualbrowser and the isotopically resolved MS spectrum was de-convoluted using the built-in Xtract algorithm.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the crystal structure of BtuMTd have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 6FFV. The mass spectrometry data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD010024.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the helpful advice from Dr. Stephanie Ruiz with the practical setup and analysis of the growth assay. We thank Dr. M. Majsnerowska (University of Groningen) for help with the construction of the EPEA-tag expression plasmids, and we would like to thank Prof. Dr. A.J.M. Driessen (University of Groningen) for the use of the ITC. We acknowledge the excellent advice, support and experimental work of the Interfaculty Mass Spectrometry Center at the Faculty of Science and Engineering of the University of Groningen. This work was supported by the European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO; EMBO Short Term Fellowship ASTF-382-2015 to S. Rempel), the Netherlands Foundation for the Advancement of Biochemistry (SSBN; SSBN Travel Grant to S. Rempel), the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO Vici grant 865.11.001 to D.J. Slotboom) and the European Research Council (ERC; ERC Starting Grant 282083 to D.J. Slotboom). For technical support, we acknowledge the beamline personnel of PXI (X06SA) and ID23-1 at SLS and ESRF, respectively.

Author contributions

D.J.S. conceived and supervised the project. S.R. performed cloning, protein production and purification, E. coli ΔFEC strain construction, growth assays, bioinformatic analyses, ITC-measurements, spectral analyses and crystallization trials. E.C. conducted spectral analyses. J.W.d.G. designed and carried out experiments to construct E. coli ΔFEC. A.G. and S.R. collected diffraction data, solved the structure and performed refinement. S.R. and D.J.S. analysed the biochemical and spectroscopic data and wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gruber K, Puffer B, Kräutler B. Vitamin B12-derivatives—enzyme cofactors and ligands of proteins and nucleic acids. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4346. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15118e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raux E, Schubert HL, Warren MJ. Biosynthesis of cobalamin (vitamin B12): a bacterial conundrum. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2000;57:1880–1893. doi: 10.1007/PL00000670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee RV, Johnston NL, Sobeski JK, Datta P, Matthews RG. Cloning and sequence analysis of the Escherichia coli metH gene encoding cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase and isolation of a tryptic fragment containing the cobalamin-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:13888–13895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martens JH, Barg H, Warren M, Jahn D. Microbial production of vitamin B12. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002;58:275–285. doi: 10.1007/s00253-001-0902-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodionov DA, Vitreschak AG, Mironov AA, Gelfand MS. Comparative genomics of the vitamin B12 metabolism and regulation in prokaryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:41148–41159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth JR, Lawrence JG, Bobik TA. Cobalamin (coenzyme B12): synthesis and biological significance. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1996;50:137–181. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Locher KP, Lee AT, Rees DC. The E. coli BtuCD structure: a framework for ABC transporter architecture and mechanism. Science. 2002;296:1091–1098. doi: 10.1126/science.1071142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadieux N, et al. Identification of the periplasmic cobalamin-binding protein BtuF of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:706–717. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.3.706-717.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DAVIS BD, MINGIOLI ES. Mutants of Escherichia coli requiring methionine or vitamin B12. J. Bacteriol. 1950;60:17–28. doi: 10.1128/jb.60.1.17-28.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slotboom DJ. Structural and mechanistic insights into prokaryotic energy-coupling factor transporters. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014;12:79–87. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodionov DA, et al. A novel class of modular transporters for vitamins in prokaryotes. J. Bacteriol. 2009;91:42–51. doi: 10.1128/JB.01208-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erkens GB, et al. The structural basis of modularity in ECF-type ABC transporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:755–760. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berntsson RPA, et al. Structural divergence of paralogous S components from ECF-type ABC transporters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13990–13995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203219109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swier LJYM, Guskov A, Slotboom DJ. Structural insight in the toppling mechanism of an energy-coupling factor transporter. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11072. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finkenwirth F, Kirsch F, Eitinger T. Solitary bio Y proteins mediate biotin transport into recombinant Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:4105–4111. doi: 10.1128/JB.00350-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genee HJ, et al. Functional mining of transporters using synthetic selections. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016;12:1015–1022. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou J, Riccardi D, Beste A, Smith JC, Parks JM. Mercury methylation by HgcA: theory supports carbanion transfer to Hg(II) Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:772–777. doi: 10.1021/ic401992y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duléry V, et al. A cyclodecapeptide ligand to vitamin B12. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:4134–4141. doi: 10.1039/b811234g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borths EL, Locher KP, Lee AT, Rees DC. The structure of Escherichia coli BtuF and binding to its cognate ATP binding cassette transporter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16642–16647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262659699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shultis DD, Purdy MD, Banchs CN, Wiener MC. Outer membrane active transport: structure of the BtuB:TonB complex. Science. 2006;312:1396–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1127694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathews FS, et al. Crystal structure of human intrinsic factor: cobalamin complex at 2.6-A resolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:17311–17316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703228104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furger E, Frei DC, Schibli R, Fischer E, Prota AE. Structural basis for universal corrinoid recognition by the cobalamin transport protein haptocorrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:25466–25476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.483271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wuerges J, Geremia S, Fedosov SN, Randaccio L. Vitamin B12 transport proteins: crystallographic analysis of beta-axial ligand substitutions in cobalamin bound to transcobalamin. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:722–729. doi: 10.1080/15216540701673413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackledge WC, et al. New facile method to measure cyanide in blood. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:4216–4221. doi: 10.1021/ac100519z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koutmos M, Gherasim C, Smith JL, Banerjee R. Structural basis of multifunctionality in a vitamin B12 -processing enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:29780–29787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.261370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J, Gherasim C, Banerjee R. Decyanation of vitamin B12 by a trafficking chaperone. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14551–14554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805989105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santos JA, et al. Functional and structural characterization of an ECF-type ABC transporter for vitamin B12. Elife. 2018;7:e35828. doi: 10.7554/eLife.35828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hvorup RN, et al. Asymmetry in the structure of the ABC transporter-binding protein complex BtuCD-BtuF. Science. 2007;317:1387–1390. doi: 10.1126/science.1145950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaehme M, Guskov A, Slotboom DJ. Crystal structure of the vitamin B3 transporter PnuC, a full-length SWEET homolog. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:1013–1015. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao Y, et al. Crystal structure of a phosphorylation-coupled saccharide transporter. Nature. 2011;473:50–54. doi: 10.1038/nature09939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finn RD, et al. HMMER web server: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W30–W38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casadaban MJ, Cohen SN. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusion and cloning in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 1980;138:179–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller, J. Experiments in Molecular Genetics (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 1972).

- 35.Thomason LC, Costantino N, Court DL. E. coli genome manipulation by P1 transduction. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2007;1:17.1–1.17.8. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0117s79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engilberge S, et al. Crystallophore: a versatile lanthanide complex for protein crystallography combining nucleating effects, phasing properties, and luminescence. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:5909–5917. doi: 10.1039/C7SC00758B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheldrick GM. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 2007;64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terwilliger TC, et al. Iterative model building, structure refinement and density modification with the PHENIX AutoBuild wizard. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2007;64:61–69. doi: 10.1107/S090744490705024X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the crystal structure of BtuMTd have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 6FFV. The mass spectrometry data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD010024.