Abstract

The mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) is a transcriptional program aimed at restoring proteostasis in mitochondria. Upregulation of mitochondrial matrix proteases and heat shock proteins was initially described. Soon thereafter, a distinct UPRmt induced by misfolded proteins in the mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS) and mediated by the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), was found to upregulate the proteasome and the IMS protease OMI. However, the IMS-UPRmt was never studied in a neurodegenerative disease in vivo. Thus, we investigated the IMS-UPRmt in the G93A-SOD1 mouse model of familial ALS, since mutant SOD1 is known to accumulate in the IMS of neural tissue and cause mitochondrial dysfunction. As the ERα is most active in females, we postulated that a differential involvement of the IMS-UPRmt could be linked to the longer lifespan of females in the G93A-SOD1 mouse. We found a significant sex difference in the IMS-UPRmt, because the spinal cords of female, but not male, G93A-SOD1 mice showed elevation of OMI and proteasome activity. Then, using a mouse in which G93A-SOD1 was selectively targeted to the IMS, we demonstrated that the IMS-UPRmt could be specifically initiated by mutant SOD1 localized in the IMS. Furthermore, we showed that, in the absence of ERα, G93A-SOD1 failed to activate OMI and the proteasome, confirming the ERα dependence of the response. Taken together, these results demonstrate the IMS-UPRmt activation in SOD1 familial ALS, and suggest that sex differences in the disease phenotype could be linked to differential activation of the ERα axis of the IMS-UPRmt.

Introduction

Mutations in the Cu,Zn,superoxide dismutase (SOD1) are responsible for approximately 20% of fALS (1). The pathophysiology of SOD1-ALS is not completely understood, and different mechanisms may participate in pathogenesis (2), including mitochondrial dysfunction (3,4). The G93A amino acid substitution in SOD1 is one of the most extensively studied mutations, both in cultured cells and in mouse models of the disease. Transgenic mice express high levels of G93A-SOD1 ubiquitously, under the control of the SOD1 endogenous promoter. They develop rapid motor neuron degeneration, resulting in paralysis and death by 4 or 5 months of age, depending on the genetic background (5). The prevalent theory for the pathogenesis of mutant SOD1 involves a gain of toxic function of G93A-SOD1. One critical observation is that misfolded SOD1 localizes to multiple cell compartments, including mitochondria. Mutant SOD1 accumulates on the mitochondrial outer membrane (6) where it interacts with some crucial proteins, such as Bcl2 (7) and VDAC (8). However, mutant SOD1 also localizes inside the mitochondrial IMS, where it accumulates and misfolds, potentially interfering with the assembly and maturation of mitochondrial proteins (9–11). The pathogenic role of the IMS pool of mutant SOD1 is also supported by evidence from cultured motor neurons, where it causes mitochondrial functional, morphological, and axonal transport abnormalities (12,13). Furthermore, we recently developed transgenic mice containing G93A-SOD1 in the IMS but not the cytoplasm (G93A IMS-SOD1), and showed that these mice develop some of the symptoms of ALS, including motor defects and mitochondrial abnormalities (14). However, one important difference between this mouse and the G93A-SOD1 mouse (where G93A-SOD1 is present in both the cytosol and the IMS) is that the IMS-only mice develop disease symptoms almost one year later. Taken together, these findings indicate that eventually the accumulation of misfolded G93A-SOD1 in the IMS is toxic for mitochondria and neurons, but they also suggest that IMS proteotoxic stress may initially activate cytoprotective responses.

A mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) was first described as a consequence of the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the matrix (15,16). These studies revealed that CHOP promotes the expression of matrix protein quality control systems, such as proteases and chaperones, namely hsp10 and hsp60 (15,16). Unlike in the matrix, there are no chaperones in the IMS, and while AAA proteases face the IMS, none of their substrates are IMS proteins (17,18).

We previously reported that the proteasome plays an active role in limiting the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the IMS (19), and that the IMS protease OMI plays a role in IMS protein quality control (19). Then, we reported that accumulation of misfolded proteins in the IMS did not activate the CHOP-hsp60 axis of the UPRmt, but rather a distinct response driven by the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) (20). The ERα axis of the UPRmt implicates a cross talk between phosphorylated Akt and the ERα, expression of the mitochondrial transcription factor NRF-1, and most importantly for the current study, the up-regulation of the proteasome and OMI (20).

The ERα dependency of the IMS-UPRmt raises intriguing questions. First, since not all cell types express ERα, how do ERα negative cells cope with the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the IMS? Our studies in breast cancer cells suggested that in the absence of the ERα, the CHOP-hsp60 could partially compensate (21). Second, since the ERα is most active in females, do the mechanisms to cope with proteotoxic stress in the IMS caused by misfolding of disease related mutant proteins, such as SOD1, differ between sexes, and if so, do they correlate with sex differences in the disease phenotype? To address this question we studied a G93A-SOD1 mouse model of familial ALS, in which females have a longer lifespan than males (22), in order to evaluate whether differences in the activation of the IMS-UPRmt could be detected in vivo and correlated with the sexual dimorphism. These questions could be directly relevant to human ALS, since the frequency of the disease is significantly higher in males than in females (23), suggesting that sex hormones and receptors may be involved in sexual dimorphism in ALS.

Results

The CHOP/hsp60 axis of the UPRmt is transiently activated in females during the symptomatic phase of the G93A-SOD1 model of fALS

The first described axis of the UPRmt is regulated by the transcription factor CHOP, which promotes the expression of proteases as well as the chaperone hsp60 (15,16). As a consequence, the promoter of hsp60 has been widely used in subsequent studies of the UPRmt, notably in C. elegans (24,25–31,32).

We therefore initiated our analysis of the UPRmt in the spinal cord of G93A-SOD1 mouse model of familial ALS by monitoring the levels of CHOP and hsp60. G93A-SOD1 transgenic mice develop an aggressive form of motor neuron disease, with paralysis onset at 90 days of age and death at 130 days of age (5). Therefore, studies were performed in male and female G93A-SOD1 mice and non-transgenic control littermates at different ages, starting at 30 and 60 days, representing pre-symptomatic disease stages, and at 90 and 120 days, representing early and late symptomatic stages, respectively.

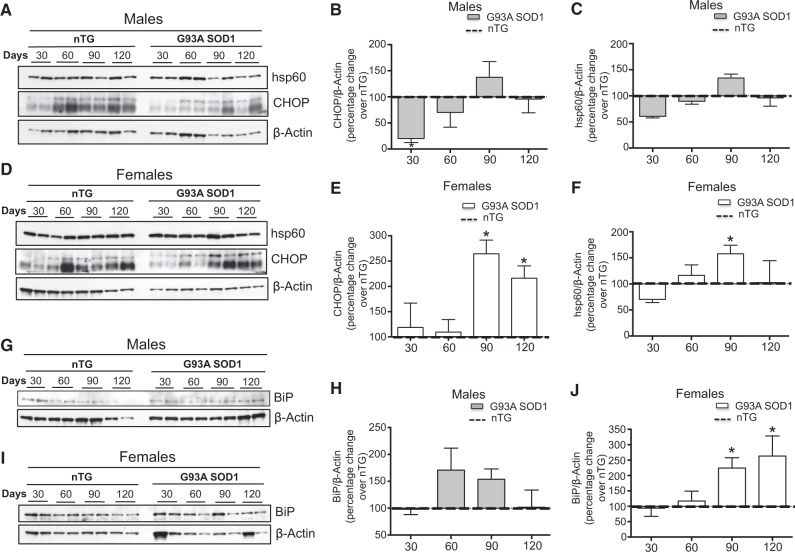

To study the effect of the mutant transgene on UPRmt markers in the spinal cord, protein levels were normalized to non-transgenic control values at each age. We found that in males, CHOP levels were significantly lower as compared to age-matched transgenic males at 30 days (Fig. 1A and B). However, at day 60 and thereafter CHOP levels in mutant mice were no longer lower. In females, there was no CHOP decrease at 30 days, and remarkably a robust CHOP increase was observed during the symptomatic phase, at 90 and 120 days (Fig. 1D and E). In female G93A-SOD1 mice, but not in males (Fig. 1A and C), hsp60 was significantly higher at 90 days of age, but it reverted to control levels at 120 days (Fig. 1D and F).

Figure 1.

The CHOP/hsp60 axis is activated during the symptomatic phase in the G93A-SOD1 model of fALS. (A) Representative western blot of hsp60 and CHOP in 2 non-transgenic males and 2 G93A-SOD1 males at day 30, 60, 90 and 120. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Quantification of the level of CHOP at each time point in males. n = 4. The level of CHOP relative to β-actin was determined for 4 non-transgenic males and the average of the 4 values set to 100 percent for each time point. The average level of CHOP relative to β-actin was also determined in 4 G93A-SOD1 transgenic males at each time point and expressed as a percentage change relative to the non-transgenic males (dotted line). (C) Quantification of the level of hsp60 in males, as in B. n = 4. (D) Representative western blot of hsp60 and CHOP in 2 non-transgenic females and 2 G93A-SOD1 females at day 30, 60, 90 and 120. β-actin was used as a loading control. (E) Quantification of the level of CHOP in females, as in B. n = 4. (F) Quantification of the level of hsp60 in females, as in B. n = 4. (G) Representative western blot of BiP in 2 non-transgenic males and 2 G93A-SOD1 males at day 30, 60, 90 and 120. β-actin was used as a loading control. (H) Quantification of the level of BiP in males, as in B. n = 4. (I) Representative western blot of BiP in 2 non-transgenic females and 2 G93A-SOD1 females at day 30, 60, 90 and 120. β-actin was used as a loading control. (J) Quantification of the level of BiP in females, as in B. n = 4. *P < 0.05 when compared to the respective non-transgenic.

Since CHOP also regulates the expression of the chaperone BiP during the UPRER independently of its role in the UPRmt, we tested whether BiP is elevated in transgenic females. We found that the levels of BiP closely matched CHOP levels at every time point tested (Fig. 1G and H). This finding is in agreement with the extensively characterized ER-stress activation in ALS mice (33). To test whether this response was specific to regions of the CNS affected by the disease, such as the spinal cord. CHOP and hsp60 were measured in the cerebellum, which is unaffected in G93A-SOD1 mice, of females at 60 and 120 days of age, when a significant increase was observed in the spinal cord. We found no significant differences in CHOP or hsp60 in the cerebellum of G93A-SOD1 transgenic mice compared to non-transgenic mice (Supplementary Material, Fig S1A–C), suggesting that the response did not take place in unaffected regions of the CNS.

Taken together, these results indicate that in ALS spinal cord there is activation of CHOP-mediated stress responses. However, there was a clear sex difference in CHOP axis activation, since increases of all markers at symptomatic stages were only observed in G93A-SOD1 females, whereas in males the responses were absent, and even below control levels at early stages.

Sex-specific activation of the ERα axis of the UPRmt in G93A-SOD1 mice

We had previously reported that accumulation of misfolded proteins in the mitochondrial IMS in breast cancer cells activates a UPRmt response pathway initiated by the phosphorylation of Akt and leading to activation of ERα, expression of the transcription factor NRF-1, increase of the IMS protease OMI, and upregulation of proteasome activity (20). The upregulation of OMI and proteasome activities was instrumental in promoting the degradation of misfolded IMS proteins (20,19). Since misfolded SOD1 is known to accumulate and aggregate in the IMS (11,34) we investigated whether the ERα axis of the UPRmt was activated in the G93A-SOD1 mouse spinal cord.

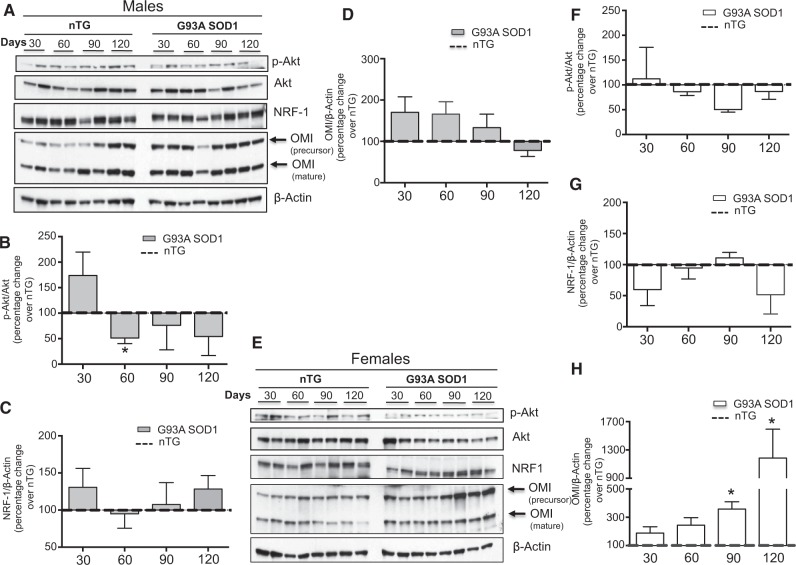

In males, we found an early elevation in Akt phosphorylation, NRF-1 and OMI at day 30 relative to non-transgenic mice (Fig. 2A–D). However the levels of phospho-Akt, NRF-1, and OMI decreased in G93A-SOD1 mice at later time points, suggesting that in these mice the IMS-UPRmt started to decline as early as 60 days of age. In females, neither phospho-Akt nor NRF-1 were elevated relative to non-transgenic mice at any of the time points tested (Fig. 2E–G). However, OMI was markedly elevated in female G93A-SOD1 mice at the symptomatic stage (Fig. 2H). We then tested whether the activation of OMI is specific to the spinal cord. We found no significant difference in OMI in the cerebellum of G93A-SOD1 transgenic mice compared to non-transgenic mice (Supplementary Material, Fig. 1D), indicating that the effect was tissue specific.

Figure 2.

The UPRmt is activated during the symptomatic phase the G93A-SOD1 model of fALS. (A) Representative western blot of phospho-Akt, Akt, NRF-1 and OMI in 2 non-transgenic males and 2 G93A-SOD1 males at day 30, 60, 90 and 120. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Quantification of the ratio of phospho-Akt to total Akt at each time point in males. n = 4. The ratio of phospho-Akt to total Akt was determined for 4 non-transgenic males and the average of the 4 values set to 100 percent for each time point. The ratio of phospho-Akt to total Akt was also determined in 4 G93A-SOD1 transgenic males at each time point and expressed as a percentage change relative to the non-transgenic males value (dotted line). (C) Quantification of the level of NRF-1 in males, as in in B. n = 4. (D) Quantification of the level of OMI in males, as in B. n = 4. (E) Representative western blot of phospho-Akt, Akt, NRF-1 and OMI in 2 non-transgenic females and 2 G93A-SOD1 females at day 30, 60, 90 and 120. β-actin was used as a loading control. (F) Quantification of the ratio of phospho-Akt to total Akt in females, as in B. n = 4. (G) Quantification of the level of NRF-1 in females, as in B. n = 4. (H) Quantification of the level of OMI in females, as in B. n = 4. *P < 0.05 when compared to the respective non-transgenic.

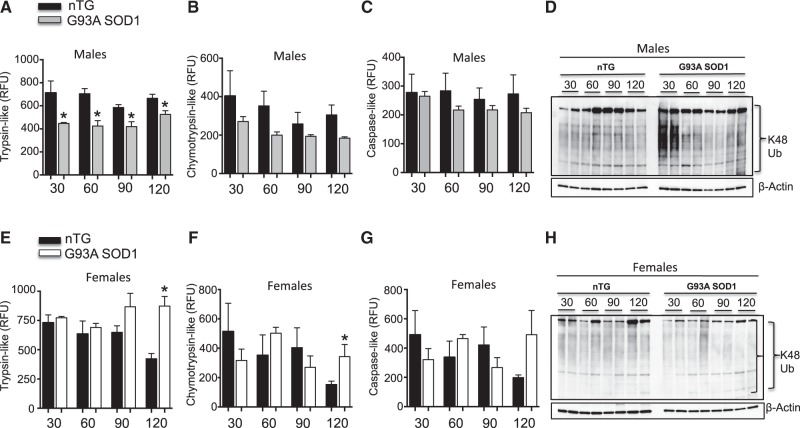

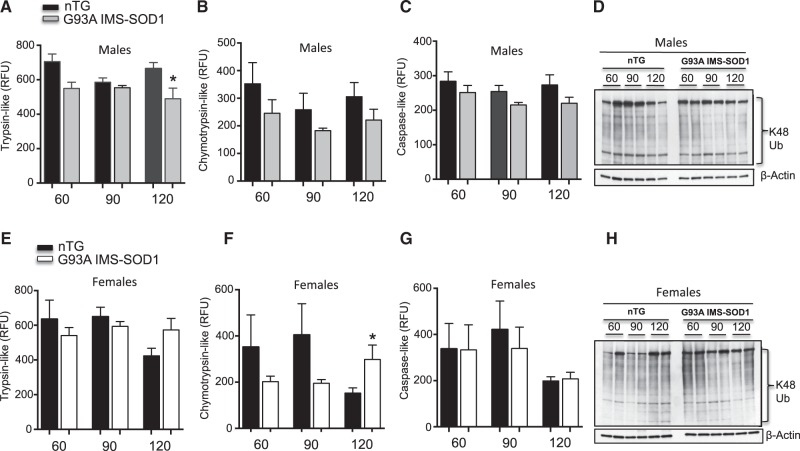

We then monitored the activity of the proteasome in spinal cord homogenates of males and females over the course of disease progression. First, proteasome activity was measured fluorimetrically, using small peptide substrates of the trypsin-like, chymotrypsin-like, and caspase-like activities. As previously reported (36), we found that the trypsin-like activity of the proteasome was decreased in male G93A-SOD1 mice compared to age matched controls (Fig. 3A). In females, there was no decline of the activity at any time point; meanwhile, the trypsin-like and chymotrypsin-like activities were significantly increased at 120 days of age (Fig. 3E and F). Again, we found no significant difference in the activity of the proteasome in the cerebellum of G93A-SOD1 transgenic females at these time points (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1E). Since the proteasome degrades ubiquitinated proteins, we studied levels of ubiquitinated proteins by western blot, using an antibody against lysine-48 ubiquitin chains, which target proteins to the proteasome. We found a general increase in the levels of proteins reactive to Ub48 antibodies in G93A-SOD1 males, which was most evident at 30 and 120 days (Fig. 3D). This finding was consistent with a decrease in the activity of the proteasome in males. In female G93A-SOD1 mice, there was no increase in the levels of proteins reactive to Ub48 antibodies (Fig. 3H), in agreement with the preserved proteasome activity.

Figure 3.

Proteasome activity is decreased in G93A-SOD1 males. (A) The trypsin-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic males (black bar) and 4 G93A-SOD1 males (gray bar). n = 4. (B) The chymotrypsin-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic males (black bar) and 4 G93A-SOD1 transgenic males (gray bar). n = 4. (C) The caspase-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic males (black bar) and 4 G93A-SOD1 transgenic males (gray bar). n = 4. (D) Representative Western blot of total lysine 48 ubiquitin chains in 2 non-transgenic and 2 G93A-SOD1 transgenic males. β-actin was used as a loading control. (E) The trypsin-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic females (black bar) and 4 G93A-SOD1 transgenic females (gray bar). n = 4. (F) The chymotrypsin-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic females (black bar) and 4 G93A-SOD1 transgenic females (gray bar). n = 4. (G) The caspase-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic females (black bar) and 4 G93A-SOD1 transgenic females (gray bar). n = 4. (H) Representative Western blot of total lysine-48 ubiquitin chains in 2 non-transgenic and 2 G93A-SOD1 transgenic females. β−actin was used as a loading control. *P < 0.05 when compared to the respective non-transgenic.

Since the G93A-SOD1 mouse overexpresses the protein, to exclude that the observed effects were due to overexpression of SOD1, we examined the levels of OMI and ubiquitin in the spinal cord of mice overexpressing wild type SOD1. We found that G93A-SOD1 females showed increased OMI relative to wild type SOD1 females (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2A and B). The level of spinal cord protein ubiquitination was also increased in G93A-SOD1 males compared to wild type SOD1 males (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2C), but was decreased in G93A-SOD1 females compared to wild type SOD1 females (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2D). These results indicated that the effects on OMI and the proteasome are caused by mutant, and not by wild type, SOD1 expression.

Overall, these findings suggest significant sex differences in the activation of the IMS-UPRmt pathway in the G93A-SOD1 mouse spinal cord. In females, we observed an increase in OMI levels and proteasome activity in symptomatic disease stages, whereas the absence of this response in males was associated with increased levels of ubiquitinated proteins.

Activation of the UPRmt is observed in G93A IMS-SOD1 mice

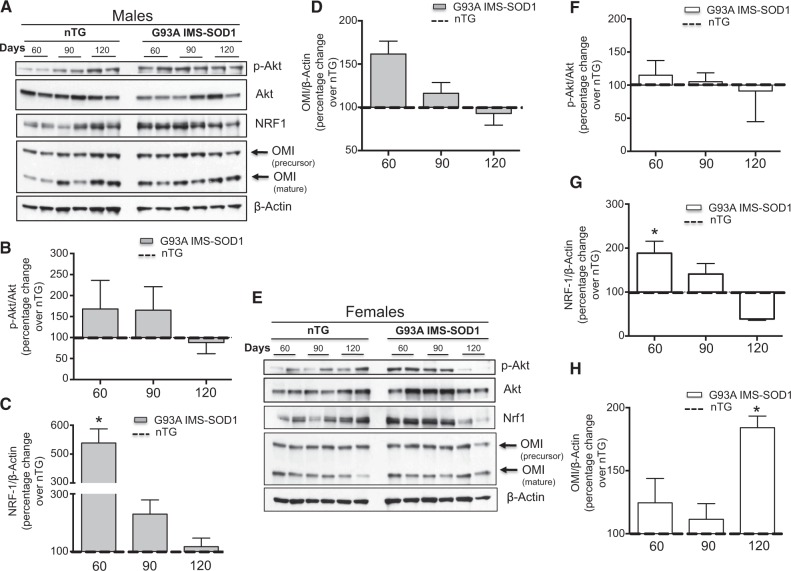

SOD1 is localized both in the cytosolic and mitochondrial IMS cellular compartment (35). Therefore, to determine whether SOD1 localized in the IMS was specifically involved in activating the UPRmt we took advantage of a transgenic mouse in which G93A-SOD1 is targeted selectively to the IMS by the addition of an N-terminus targeting sequence (G93A IMS-SOD1). As a result, G93A-SOD1 is absent from the cytosol and only concentrated in the IMS (14). Since the pre-symptomatic phase is much longer in G93A IMS-SOD1mice than in the untargeted model (14), we only analyzed the UPRmt markers and proteasome activity at 60, 90 and 120 days.

In G93A IMS-SOD1 males, NRF-1 was significantly increased relative to the non-transgenic controls only at day 60, while no other markers of the IMS-UPRmt were significantly different (Fig. 4A–D). In females, while phospho-Akt did not differ from controls, NRF-1 was significantly increased G93A IMS-SOD1 at 60 days (Fig. 4E–G). This observation indicates that, unlike in the untargeted model, mutant SOD1 targeted to the IMS leads to an early activation of NRF-1 in both males and females. Importantly, in female G93A IMS-SOD1 mice, OMI was significantly elevated compared to controls at 120 days of age, similarly to the untargeted females (Fig. 4H). This suggested that localization of mutant SOD1 in the IMS was sufficient to cause OMI elevation in female mice.

Figure 4.

The UPRmt is activated in G93A IMS-SOD1 mice. (A) Representative western blot of phospho-Akt, Akt, NRF-1 and OMI in 2 non-transgenic males and 2 G93A IMS-SOD1 males at day 60, 90 and 120. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Quantification of the ratio of phospho-Akt to total Akt at each time point in males. n = 4. The ratio of phospho-Akt to total Akt was determined for 4 non-transgenic males and the average of the 4 values set to 100 percent for each time point. The ratio of phospho-Akt to total Akt was also determined in 4 G93A IMS-SOD1 transgenic males and the average of these 4 values was expressed as a percentage change relative to the non-transgenic males (dotted line). (C) Quantification of the level of NRF-1 in males, as in B. n = 4. (D) Quantification of the level of OMI in males, as in B. n = 4. (E) Representative western blot of phospho-Akt, Akt, NRF-1 and OMI in 2 non-transgenic females and 2 G93A IMS-SOD1 females at day 60, 90 and 120. β-actin was used as a loading control. (F) Quantification of the ratio of phospho-Akt to total Akt in females, as in B. n = 4. (G) Quantification of the level of NRF-1 in females, as in B. n = 4. (H) Quantification of the level of OMI in females, as in B. n = 4. *P < 0.05 when compared to the respective non-transgenic.

The activity of the proteasome in G93A IMS-SOD1 males was unaffected until 120 days of age, when a decrease in trypsin-like activity was observed (Fig. 5A), while the other activities were unchanged at all-time points (Fig. 5B and C). This suggested that IMS-restricted protein was less effective in causing proteasomal dysfunction than untargeted, mostly cytosolic, G93A-SOD1. The accumulation of lysine-48 ubiquitin was less in G93A IMS-SOD1 males than age matched controls (Fig. 5D), further suggesting that the cytosolic, and not the IMS, G93A-SOD1 was responsible for proteasome impairment.

Figure 5.

Monitoring the proteasome activity in the G93A IMS-SOD1 mouse model over disease progression. (A) The trypsin-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic males (black bar) and 4 G93A IMS-SOD1 transgenic males (gray bar). n = 4. (B) The chymotrypsin-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic males (black bar) and 4 G93A IMS-SOD1 transgenic males (gray bar). n = 4. (C) The caspase-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic males (black bar) and 4 G93A IMS-SOD1 transgenic males (gray bar). n = 4. (D) Representative Western blot of total lysine 48 ubiquitin chains in 2 non-transgenic and 2 G93A IMS-SOD1 transgenic males. β-actin was used as a loading control. (E) The trypsin-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic females (black bar) and 4 G93A IMS-SOD1 transgenic females (gray bar). n = 4. (F) The chymotrypsin-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic females (black bar) and 4 G93A IMS-SOD1 transgenic females (gray bar). n = 4. (G) The caspase-like activity of the 26S proteasome in 4 non-transgenic females (black bar) and 4 G93A IMS-SOD1 transgenic females (gray bar). n = 4. (H) Representative Western blot of total lysine-48 ubiquitin chains in 2 non-transgenic and 2 IMS-only G93A-SOD1 transgenic females. β-actin was used as a loading control. *P < 0.05 when compared to respective non-transgenic.

In female G93A IMS-SOD1 mice, the proteasome activity was not decreased at any time point, and, similar to the untargeted G93A-SOD1 females, the chymotrypsin activity was increased at 120 days of age (Fig. 5E–G). Like males, female G93A IMS-SOD1 mice did not exhibit an increase of lysine-48 ubiquitin (Fig. 5H).

Having established that NRF-1 is increased at day 60 in male G93A IMS-SOD1 mice and that OMI is elevated at day 120 in female G93A IMS-SOD1 mice, we examined NRF-1 and OMI in wild type IMS-SOD1 mice at 60 and 120 days, respectively. We found that in both cases, the effect was specific to G93A IMS-SOD1 mice (Supplementary Material, Fig. 2E and F). These results indicated that the effects on NRF-1 and OMI are caused by mutant, and not by wild type, SOD1 in the mitochondrial IMS.

Collectively, these results suggest that the IMS localization of G93A-SOD1 is responsible for the activation of the IMS-UPRmt as demonstrated by the elevation of NRF-1 and OMI. They also suggest that the cytosolic localization of G93A-SOD1 is necessary to cause proteasomal dysfunction, which was absent in the G93A IMS-SOD1 mice.

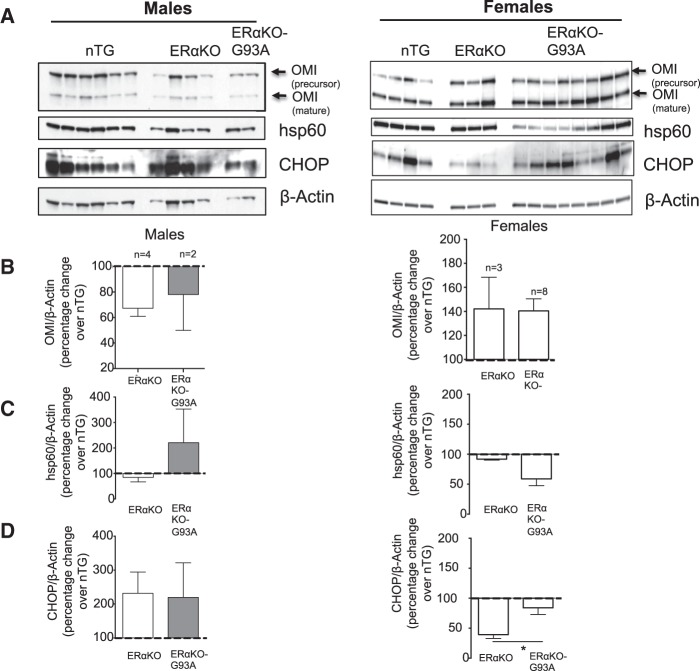

Genetic ablation of ERα in G93A-SOD1 mice abolishes the activation of OMI but stimulates the CHOP/hsp60 axis of the UPRmt

In cancer cells, we reported that inhibition of the ERα by shRNA prevented the activation of OMI in response to the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the IMS (20). Since OMI was the most affected marker of the activation of the UPRmt in female G93A-SOD1 mice, we tested whether genetic ablation of the ERα in this model would affect the expression of OMI. We therefore crossed the G93A-SOD1 mouse with an ERα knockout mouse. We obtained wild type non transgenic mice, ERα knockout mice (ERαKO), and ERαKO-G93A-SOD1 mice. We tested the UPRmt markers in the three genotypes and found that in males and females ERαKO-G93A-SOD1 mice OMI was not upregulated relative to both ERα knockout and wild type non-transgenic controls (Fig. 6A and B).

Figure 6.

Genetic ablation of the ERα abolishes the activation of OMI but stimulates the CHOP/hsp60 axis of the UPRmt. (A) Western blot of non-transgenic, ERαKO or ERαKO-G93A males (left) and females (right) of OMI, hsp60 and CHOP. β-actin is used as a loading control. All mice were harvested at day 60. (B) Quantification of the ratio of OMI to β−actin. For this experiment the number of mice per group varied: non-transgenic males, n = 6, ERαKO males, n= 4, ERαKO-G93A knockout males, n = 2, non-transgenic females, n = 4, ERαKO females, n = 3, ERαKO-G93A females, n = 8. Because n = 2 in some groups, the males and the females were combined to perform statistical analyses. (C) Quantification of the level of hsp60 in non-transgenic, ERαKO or ERαKO-G93A males and females. The quantification was performed as described in B. (D) Quantification of the level of CHOP in non-transgenic, ERαKO or ERαKO-G93A males and females. The quantification was performed as described in B. *P < 0.05 when compared to respective non-transgenic.

We then analyzed levels of CHOP and hsp60 in these mice. We found that in female ERαKO-G93A-SOD1 mice there was an elevation in CHOP, compared to ERαKO females (Fig. 6C and D) and was not observed in G93A-SOD1 mice (Fig. 1). This result suggested that in the absence of the ERα-dependent axis of the UPRmt, an ERα-independent axis, involving CHOP, but not OMI, could be activated as a compensatory mechanism. This result is in agreement with our finding in breast cancer cell lines, where in the absence of ERα the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the IMS activates CHOP (21).

Discussion

The ERα axis of the UPRmt was first identified in breast cancer cells using the accumulation of misfolded protein specifically in the IMS as a tool to dissect the relative contribution of the matrix and IMS in the activation of the UPRmt (20). However, in vivo validation of this pathway in a disease relevant mouse model of neurodegeneration was lacking. Since G93A-SOD1 misfolds and accumulates in the IMS, this mouse model was ideal to investigate the IMS-UPRmtin vivo in a mammalian model of familial ALS.

The findings from this study confirmed previous observations and revealed a novel role of the IMS-specific axis of UPRmt. Our results concur with previous observations that the CHOP-hsp60 axis is activated (28) and the proteasome inhibited during disease progression (36). While these results validate the hypothesis that the UPRmt is active in G93A-SOD1 mice, they also bring additional information regarding these effects according to sex. Notably, while the proteasome was inhibited in males, it was activated in females. Differential proteasomal responses could have a disease-modifying function, but also directly participate in the accumulation of misfolded SOD1 in mitochondria, since it was shown that degradation of IMS misfolded proteins involves the proteasome (37).

In addition to proteasome activation, our data revealed that the IMS protease OMI is upregulated in females. Therefore, both components of IMS protein quality control are upregulated in females. This result is consistent with the more potent role of the ERα in females.

The G93A IMS-SOD1 mouse model made it possible to dissect the specific contribution of the IMS fraction of G93A-SOD1 to the activation of the UPRmt, and revealed that this fraction is sufficient to promote the activation of OMI and the proteasome in females. In addition, the comparison between the G93A-SOD1 and G93A IMS-SOD1 models showed that the inhibition of the proteasome observed in males is mainly dependent on the cytosolic mutant SOD1. Further, since OMI and NRF-1 were higher in G93A IMS-SOD1 males than in the G93A-SOD1 mice, collectively these results support the notion that the IMS fraction of mutant SOD1 plays a direct role in the activation of the UPRmt.

One of the most striking effects observed was the activation of OMI in G93A-SOD1 female mice. Interestingly, in sporadic ALS patient post-mortem studies, OMI was found to accumulate in spinal motor neurons (38). On the other hand, a decrease in OMI was reported to contribute to neurodegeneration (39–41). In light of these findings, we propose that increased OMI levels induced by the UPRmt may enhance protein quality control in the IMS and delay the onset of mitochondrial damage. However, as mitochondrial damage progresses, despite its increase, OMI becomes insufficient to maintain the integrity of mitochondria. In fact, since the release of OMI in the cytosol upon mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization plays a role in apoptosis, an initial protective effect of elevated OMI in the IMS could eventually contribute to the acceleration of cell death, if mitochondrial damage promotes its release into the cytosol. This could contribute possibly to the delay in disease progression in ALS female mice relative to males.

Finally, our results in the ERαKO mice suggested that, as we previously reported in breast cancer cells (20), upon inhibition of the ERα, the CHOP axis of the UPRmt could play a compensatory role in an attempt to maintain the integrity of the mitochondria. The UPRmt pathway is rapidly gaining attention, and this study is the first to identify activation of this pathway in a disease relevant model in vivo. Considering that the UPRmt regulates the communication between stressed mitochondria and the nucleus, it is likely to be implicated in the pathology of several diseases with mitochondrial involvement. Importantly, as some tissues and cell types do not express ERα and the function of the ERα is tissue specific (42,43) one interesting possible implication of our findings is that the UPRmt could help explain some aspects of the sex differences and cell type specificity observed in ALS. Clearly, more work needs to be done to determine if our findings in the SOD1 mouse model apply to humans affected by the much more common sporadic forms of ALS, but the higher incidence of sporadic ALS in males (23) suggests that estrogen hormones and their receptors could indeed be involved in sex differences through the ERα axis of the UPRmt. Moreover, considering that estrogen has been reported to affect the severity of primary mitochondrial diseases with strong male bias, such as Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy (44), whether this pathway also plays a role in gender differences in these diseases remains to be explored.

Materials and Methods

Animals

We used the B6SJL-Tg(SOD1*G93A)1Gur/J, the Tg(SOD1)2Gur, the B6SJL-Tg(Prnp-Immt/SOD1*G93A)7Gmnf/J, and the B6SJL-Tg(Prnp-Immt/SOD1)1Gmnf/J from The Jackson Laboratory. Estrogen Receptor α knockout animals with the G93A-SOD1 mutation (ERαKO-G93A) in the C57BL/6J congenic background were generated by crossing the G93A-SOD1 line (B6.Cg-Tg (SOD1-G93A)1Gur/J) with ERαKO heterozygote mice (B6.129P2-Esr1tm1Ksk/J), both available from The Jackson Laboratory. Females heterozygous for ERαKO were bred with males heterozygous for ERαKO, which also had the G93A-SOD1 mutation. At the indicated ages, animals were sacrificed and tissues harvested in storage solution (10mM Tris pH 7.4, 320 mM sucrose, 20% DMSO), and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

All experiments were approved by the Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Principles of laboratory animal care (NIH publication No. 86-23, revised 1985) were followed, as well as specific national laws (e.g. the current version of the German Law on the Protection of Animals), where applicable.

Western blotting

Spinal cords were lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer, sonicated for 1 s at an amplitude of 20% and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 20 min. Proteins were separated on 10% or 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX gels (Bio-Rad,CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose blotting membrane (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Membranes were probed with primary antibodies against phosphorylated-Akt (Cell Signaling), Akt (Cell Signaling), Omi/HtrA2 (Biovison), NRF-1 (Abcam), hsp60 (BD Bioscience), CHOP (Cell Signaling), BiP (BD Bioscience), Ub-48 (EMD Millipore) and Actin (EMD Millipore) overnight at 4°C. Blots were then probed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch) or anti-rabbit (Thermo Scientific) secondary antibodies and detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare or Millipore).

Proteasome assay

Spinal cord lysates (10ug) were incubated in proteasome activity assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) with 10uM trypsin fluorogenic substrate Ac-Ala-Leu-Ala-AMC (Ac-ALA-AMC) or chymotrypsin fluorogenic substrate succinly-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Suc-LLVY-AMC), or caspase fluorogenic substrates N-acetyl-Gly-Pro-Leu-Ala-AMC (Ac-GPLA-AMC) for 3 h at 37°C. Release of free hydrolysed 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) groups was measured at 380nm excitation and 460nm emission using SpectraMax M5e microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance between two datasets. *P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Instat software.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material is available at HMG online.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (R01NS084486 to D.G. and G.M., R01NS062055 to G.M.).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Rosen D.R. (1993) Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature, 364, 362.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ilieva H., Polymenidou M., Cleveland D.W. (2009) Non-cell autonomous toxicity in neurodegenerative disorders: ALS and beyond. J. Cell Biol., 187, 761–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hervias I., Beal M.F., Manfredi G. (2006) Mitochondrial dysfunction and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve., 33, 598–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shi P., Gal J., Kwinter D.M., Liu X., Zhu H. (2010) Mitochondrial dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1802, 45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gurney M.E., Pu H., Chiu A.Y., Dal Canto M.C., Polchow C.Y., Alexander D.D., Caliendo J., Hentati A., Kwon Y.W., Deng H.X., and., et al. (1994) Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science, 264, 1772–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vande Velde C., Miller T.M., Cashman N.R., Cleveland D.W. (2008) Selective association of misfolded ALS-linked mutant SOD1 with the cytoplasmic face of mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A, 105, 4022–4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pedrini S., Sau D., Guareschi S., Bogush M., Brown R.H. Jr., Naniche N., Kia A., Trotti D., Pasinelli P. (2010) ALS-linked mutant SOD1 damages mitochondria by promoting conformational changes in Bcl-2. Hum. Mol. Genet., 19, 2974–2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Israelson A., Arbel N., Da Cruz S., Ilieva H., Yamanaka K., Shoshan-Barmatz V., Cleveland D.W. (2010) Misfolded mutant SOD1 directly inhibits VDAC1 conductance in a mouse model of inherited ALS. Neuron, 67, 575–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vijayvergiya C., Beal M.F., Buck J., Manfredi G. (2005) Mutant superoxide dismutase 1 forms aggregates in the brain mitochondrial matrix of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice. J. Neurosci., 25, 2463–2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kawamata H., Manfredi G. (2008) Different regulation of wild-type and mutant Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase localization in mammalian mitochondria. Hum. Mol. Genet., 17, 3303–3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferri A., Cozzolino M., Crosio C., Nencini M., Casciati A., Gralla E.B., Rotilio G., Valentine J.S., Carri M.T. (2006) Familial ALS-superoxide dismutases associate with mitochondria and shift their redox potentials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A, 103, 13860–13865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Magrane J., Hervias I., Henning M.S., Damiano M., Kawamata H., Manfredi G. (2009) Mutant SOD1 in neuronal mitochondria causes toxicity and mitochondrial dynamics abnormalities. Hum. Mol. Genet., 18, 4552–4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cozzolino M., Pesaresi M.G., Amori I., Crosio C., Ferri A., Nencini M., Carri M.T. (2009) Oligomerization of mutant SOD1 in mitochondria of motoneuronal cells drives mitochondrial damage and cell toxicity. Antioxid. Redox. Signal., 11, 1547–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Igoudjil A., Magrane J., Fischer L.R., Kim H.J., Hervias I., Dumont M., Cortez C., Glass J.D., Starkov A.A., Manfredi G. (2011) In vivo pathogenic role of mutant SOD1 localized in the mitochondrial intermembrane space. J. Neurosci., 31, 15826–15837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martinus R.D., Garth G.P., Webster T.L., Cartwright P., Naylor D.J., Hoj P.B., Hoogenraad N.J. (1996) Selective induction of mitochondrial chaperones in response to loss of the mitochondrial genome. Eur. J. Biochem., 240, 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao Q., Wang J., Levichkin I.V., Stasinopoulos S., Ryan M.T., Hoogenraad N.J. (2002) A mitochondrial specific stress response in mammalian cells. Embo J., 21, 4411–4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koppen M., Langer T. (2007) Protein degradation within mitochondria: versatile activities of AAA proteases and other peptidases. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol., 42, 221–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Augustin S., Nolden M., Muller S., Hardt O., Arnold I., Langer T. (2005) Characterization of peptides released from mitochondria: evidence for constant proteolysis and peptide efflux. J. Biol. Chem., 280, 2691–2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Radke S., Chander H., Schafer P., Meiss G., Kruger R., Schulz J.B., Germain D. (2008) Mitochondrial protein quality control by the proteasome involves ubiquitination and the protease Omi. J. Biol. Chem., 283, 12681–12685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Papa L., Germain D. (2011) Estrogen receptor mediates a distinct mitochondrial unfolded protein response. J. Cell Sci., 124, 1396–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Papa L., Germain D. (2014) SirT3 regulates the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell Biol., 34, 699–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heiman-Patterson T.D., Deitch J.S., Blankenhorn E.P., Erwin K.L., Perreault M.J., Alexander B.K., Byers N., Toman I., Alexander G.M. (2005) Background and gender effects on survival in the TgN(SOD1-G93A)1Gur mouse model of ALS. J. Neurol. Sci., 236, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCombe P.A., Henderson R.D. (2010) Effects of gender in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Gend. Med., 7, 557–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Benedetti C., Haynes C.M., Yang Y., Harding H.P., Ron D. (2006) Ubiquitin-like protein 5 positively regulates chaperone gene expression in the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Genetics, 174, 229–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fiorese C.J., Schulz A.M., Lin Y.F., Rosin N., Pellegrino M.W., Haynes C.M. (2016) The Transcription Factor ATF5 Mediates a Mammalian Mitochondrial UPR. Curr. Biol., 26, 2037–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Haynes C.M., Petrova K., Benedetti C., Yang Y., Ron D. (2007) ClpP mediates activation of a mitochondrial unfolded protein response in C. elegans. Dev. Cell, 13, 467–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin Y.F., Schulz A.M., Pellegrino M.W., Lu Y., Shaham S., Haynes C.M. (2016) Maintenance and propagation of a deleterious mitochondrial genome by the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Nature, 533, 416–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mohrin M., Shin J., Liu Y., Brown K., Luo H., Xi Y., Haynes C.M., Chen D. (2015) Stem cell aging. A mitochondrial UPR-mediated metabolic checkpoint regulates hematopoietic stem cell aging. Science, 347, 1374–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nargund A.M., Fiorese C.J., Pellegrino M.W., Deng P., Haynes C.M. (2015) Mitochondrial and nuclear accumulation of the transcription factor ATFS-1 promotes OXPHOS recovery during the UPR(mt). Mol. Cell, 58, 123–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nargund A.M., Pellegrino M.W., Fiorese C.J., Baker B.M., Haynes C.M. (2012) Mitochondrial import efficiency of ATFS-1 regulates mitochondrial UPR activation. Science, 337, 587–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Durieux J., Wolff S., Dillin A. (2011) The cell-non-autonomous nature of electron transport chain-mediated longevity. Cell, 144, 79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tian Y., Merkwirth C., Dillin A. (2016) Mitochondrial UPR: A Double-Edged Sword. Trends Cell Biol., 26, 563–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matus S., Valenzuela V., Medinas D.B., Hetz C. (2013) ER Dysfunction and Protein Folding Stress in ALS. Int. J. Cell Biol., 2013, 674751.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kawamata H., Manfredi G. (2010) Import, maturation, and function of SOD1 and its copper chaperone CCS in the mitochondrial intermembrane space. Antioxid. Redox. Signal, 13, 1375–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Okado-Matsumoto A., Fridovich I. (2001) Subcellular distribution of superoxide dismutases (SOD) in rat liver: Cu,Zn-SOD in mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 38388–38393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kabashi E., Durham H.D. (2006) Failure of protein quality control in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1762, 1038–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bragoszewski P., Gornicka A., Sztolsztener M.E., Chacinska A. (2013) The ubiquitin-proteasome system regulates mitochondrial intermembrane space proteins. Mol Cell Biol., 33, 2136–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kawamoto Y., Ito H., Kobayashi Y., Suzuki Y., Akiguchi I., Fujimura H., Sakoda S., Kusaka H., Hirano A., Takahashi R. (2010) HtrA2/Omi-immunoreactive intraneuronal inclusions in the anterior horn of patients with sporadic and Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) mutant amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol., 36, 331–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moisoi N., Klupsch K., Fedele V., East P., Sharma S., Renton A., Plun-Favreau H., Edwards R.E., Teismann P., Esposti M.D., et al. (2009) Mitochondrial dysfunction triggered by loss of HtrA2 results in the activation of a brain-specific transcriptional stress response. Cell Death Differ., 16, 449–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Strauss K.M., Martins L.M., Plun-Favreau H., Marx F.P., Kautzmann S., Berg D., Gasser T., Wszolek Z., Muller T., Bornemann A., et al. (2005) Loss of function mutations in the gene encoding Omi/HtrA2 in Parkinson's disease. Hum. Mol. Genet., 14, 2099–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jones J.M., Datta P., Srinivasula S.M., Ji W., Gupta S., Zhang Z., Davies E., Hajnoczky G., Saunders T.L., Van Keuren M.L., et al. (2003) Loss of Omi mitochondrial protease activity causes the neuromuscular disorder of mnd2 mutant mice. Nature, 425, 721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bhat-Nakshatri P., Wang G., Appaiah H., Luktuke N., Carroll J.S., Geistlinger T.R., Brown M., Badve S., Liu Y., Nakshatri H. (2008) AKT alters genome-wide estrogen receptor alpha binding and impacts estrogen signaling in breast cancer. Mol. Cell Biol., 28, 7487–7503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Carroll J.S., Meyer C.A., Song J., Li W., Geistlinger T.R., Eeckhoute J., Brodsky A.S., Keeton E.K., Fertuck K.C., Hall G.F., et al. (2006) Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat. Genet., 38, 1289–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Giordano C., Montopoli M., Perli E., Orlandi M., Fantin M., Ross-Cisneros F.N., Caparrotta L., Martinuzzi A., Ragazzi E., Ghelli A., et al. (2011) Oestrogens ameliorate mitochondrial dysfunction in Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Brain, 134, 220–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.