Abstract

Although studies have suggested that community social capital contributes to narrow income-based inequality in depression, the impacts may depend on its components. Our multilevel cross-sectional analysis of data from 42,208 men and 45,448 women aged 65 years or older living in 565 school districts in Japan found that higher community-level civic participation (i.e., average levels of group participation in the community) was positively associated with the prevalence of depressive symptoms among the low-income groups, independent of individual levels of group participation. Two other social capital components (cohesion and reciprocity) did not significantly alter the association between income and depressive symptoms.

Keywords: Social capital, Health inequality, Depressive symptoms, Ageing, Multilevel modeling, Japan

Highlights

-

•

Community social capital might be protective towards depression in older adults.

-

•

Community civic participation may enlarge the income-based gap in depression.

-

•

Considering bright and dark sides of social capital is necessary for intervention.

1. Introduction

Ageing is a major risk factor for many chronic diseases and physical and mental illnesses. Specifically, in Japan, Wada demonstrated that in the years 2000/2001, 33.5% of older people in four rural towns had depressive symptoms, defined as scoring more than 5 points on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) (Wada et al., 2004). Depression can cause other critical health issues including suicide, frailty, functional disability, and mortality (Waern et al., 2003, Kondo et al., 2008, Wada et al., 2004). Therefore, depression is a key target of the public health actions targeted to older adults in Japan and worldwide (World Health Organization, 2010, Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, 2012).

Socioeconomic inequalities in the prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults are also major targets of public health actions, as social epidemiology studies have identified depression as strongly concentrated among the socially disadvantaged older population (Murata et al., 2008, Cole and Dendukuri, 2003).

Depression can be affected by psychosocial conditions in the community. Recent studies have suggested that high community social capital—defined as “resources that are accessed by individuals as a result of their membership in a network or a group”—is associated with fewer individual risks for depressive symptoms in older adults (Ivey et al., 2015, Kawachi et al., 1999). However, the evidence is scarce on whether or not high community social capital is associated with the smaller socioeconomic disparity in depressive symptoms. Poverty puts one at risk for social isolation, which, in turn, puts one at risk for depression. Therefore, we could hypothesize that communities rich in social capital may contribute more to those who are worse off, according to their contextual characteristics as positive externalities (Berkman et al., 2014). Our previous ecological study in Japan showed an inverse relationship between community-level social capital and income-based inequality in depressive symptoms among older adults (Haseda et al., 2018). Although this ecological study supported the hypothesis, it could not distinguish the compositional and contextual effects of community social capital in reducing income-based inequality in depressive symptoms; thus, a more sophisticated study is necessary: that is, a multilevel analysis to assess whether or not community-level social capital modifies the association between individual income and the prevalence of depressive symptoms. Moreover, we also hypothesize that the association between community social capital and income-based inequality in depressive symptoms may differ by the dimensions of the former. Specifically, based on recent discussions, we focused on the structural and cognitive aspects of community social capital, which when evaluated as cognitive social cohesion may contribute to individuals who comprise the community universally, regardless of socioeconomic background. This is because people inhabiting a community can reap the benefits of social cohesion equally, given that cohesion is nonexcludable (Berkman et al., 2014). In theory and practice, cognitive social capital should and has been evaluated in terms of the levels of social cohesion (trust and reciprocity) (Berkman et al., 2014). However, community social capital evaluated as a structural aspect (levels of civic participation or the opportunities for participation (Berkman et al., 2014)) may not necessarily benefit all people. This may be specifically so in a highly segregated community, because the organizations for the rich and the poor may be completely different, making positive spillover less likely to occur. Hence, the average level of structural social capital cannot reflect equality in the opportunities for social interaction. To differentiate the structural and cognitive aspects of community social capital, we used a recently developed validated social capital scale.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the variable associations between individual income and depressive symptoms across communities with different levels of structural and cognitive social capital, using large-scale multilevel data of older Japanese adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Data

We used cross-sectional data of the 2013 wave of the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES). The JAGES 2013 wave was an anonymous self-administered mail-in survey across 30 municipalities in 13 out of 47 prefectures in Japan. Although the participating municipalities are not nationally representative, they vary significantly and include small rural towns to large metropolitan cities from areas in the North (Hokkaido) and South (Kumamoto) ends. Their population ranged between 1246 and 3.7 million people, and the share of the older population was between 18.0% and 47.6% (Statistics Bureau; Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 2013). Participants who were aged 65 years or older were functionally independent in their daily living; that is, they did not receive benefits from public long-term care insurance at that time. Participants living in 16 large municipalities were randomly selected by multistage sampling, while all eligible individuals living in 14 small municipalities were selected. We mailed 193,694 questionnaires, of which 137,736 were returned (response rate = 71.1%). We excluded the responses without valid values for key variables (age, gender, the area of residence, and depressive symptoms) from the analyses.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Depressive symptoms

We used the Japanese short version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) developed for self-administered surveys to assess depressive symptoms (Yesavage and Sheikh, 1986, Niino et al., 1991). We set a cut-off score of 4/5, which has been universally adopted as indicating a depressive tendency based on validation studies (Nyunt et al., 2009).

2.2.2. Income

We gathered information on annual income by asking, “What was your pretax annual household income for 2012 (including pension)?” in 15 predetermined categories (in thousands of yen). We calculated household income equivalized by dividing each response by the square root of the number of household members and further dividing them into tertiles.

2.2.3. Community social capital

We used the Health-Related Social Capital Scale developed and validated among older Japanese people by Saito et al. (2017). The scale has three subscales that assess civic participation, social cohesion, and reciprocity. Scores for each subscale are derived from the summation of the percentage that responded to multiple questions and are standardized. Items for civic participation concern participation in five types of groups in the community: volunteering, sports, hobby, culture, and skill teaching. Social cohesion items concern trust (“Do you think that people living in your area can be trusted, in general?”), others’ perceived intention to help (“Do you think that people living in your area try to help others in most situations?”), and attachment to the residential area (“How attached are you to the area in which you live?”). The sum of the percentage of those who answered “very” or “moderately” to the items formed the score. Reciprocity items concern having someone to provide or receive emotional support or to receive instrumental support: “Do you have someone who listens to your concerns and complaints?” “Do you listen to someone's concerns and complaints?” and “Do you have someone who looks after you when you are sick and confined to a bed for a few days?” The sum of the percentage of those who designated anyone to the questions formed the score.

2.3. Covariates

Referring to recent social epidemiology studies, we considered the following variables as potential confounding factors in the association between income and depression among older adults: age, years of education (less than nine years or not), marital status (having a spouse or not), living alone or not, comorbidities (having past medical history of stroke, heart disease, diabetes mellitus, cancer, dementia, or Parkinson's disease), and frequency of going out (Chang-Quan et al., 2010, Yan et al., 2011, Stahl et al., 2016, Evans et al., 2005, Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2010). We also considered the fixed effect of each municipality.

2.4. Statistical analysis

We conducted a multilevel Poisson regression analysis incorporating both individuals and school districts. As recent studies report that community-level factors had different impacts with regard to gender, we modeled men and women separately (Eriksson et al., 2011; Pattyn et al., 2011; Haseda et al., 2018). School districts are the smallest areal units identifiable using JAGES data. Within 30 municipalities, there are 565 school districts. The district originally represents the district unit determining the catchment area of each public school. We chose to use this areal unit because a school district is likely to represent Japanese “communities” developed in its local history, such as “kyu-son” (former village areas). We believed that the school district could represent the adequate areal size to reflect community social capital that could work as the informal resource contributing to community autonomy.

We statistically investigated the effect modifications of community social capital in terms of civic participation, social cohesion, and reciprocity on the association between income and depressive symptoms. To do so, in the Poisson regression, we modeled cross-level interaction terms between each standardized community social capital component and income besides those variables’ main effects. In addition to the covariates explained above, we modeled individual responses to each social capital component as potential confounders. Each individual-level social capital component was binarized in our analyses; that is, those who participated in any of the five kinds of groups in their community were considered to engage in individual civic participation; those who showed trust, others’ intention to help, or attachment to the residential area were regarded as individually socially cohesive; and those who answered that they have someone to provide or receive emotional or instrumental support were considered to have individual social support. We took into account missing values assigning dummy variables for the missing category. We used Stata version 14.1 for these statistical analyses. (Stata Corp. Texas, USA)

3. Results

We analyzed 87,656 individuals (42,208 men and 45,448 women) after excluding those with missing responses to key variables (n = 7996 for age and gender, n = 28,786 for the area of residence, and n = 2506 for depressive symptoms) among eligible subjects. Descriptive statistics showed that, similar to previous studies, the percentage of people who showed depressive symptoms was more prevalent in lower-income groups. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in lowest-, middle-, and highest-income groups were 42.2%, 30.6%, and 18.5% among men and 39.3%, 28.6%, and 19.5% among women, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of participants with depressive symptoms.

| Participants (n = 87,656) | Have depressive symptoms |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (Men/Women) | Men (n = 12,704) |

Women (n = 13,861) |

|||

| n or mean [SD] | n (%) or mean [SD] | n (%) or mean [SD] | |||

| Age | |||||

| 65–74 | 52,294 (25,531/ 26,763) | 6996 | (25.3) | 7220 | (23.4) |

| 75–84 | 29,963 (14,333/ 15,630) | 4808 | (29.5) | 5317 | (27.4) |

| 85 and older | 5399 (2344/ 3055) | 900 | (32.0) | 1324 | (34.2) |

| Income | |||||

| T1 (Low) | 22,816 (10,349/ 12,467) | 4369 | (38.3) | 4896 | (34.0) |

| T2 (Middle) | 20,047 (10,880/ 9367) | 3268 | (28.2) | 2683 | (25.0) |

| T3 (High) | 28,928 (15,366/ 13,562) | 2847 | (17.1) | 2639 | (17.3) |

| Missing | 15,865 (5813/ 10,052) | 2220 | (30.9) | 3643 | (26.6) |

| Education | |||||

| < 9 years | 37,669 (16,690/ 20,979) | 6132 | (32.6) | 7344 | (29.1) |

| > =9 years | 48,481 (24,904/ 23,577) | 6309 | (23.2) | 6102 | (22.3) |

| Missing | 1506 (614/ 892) | 263 | (31.1) | 415 | (28.1) |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| none | 58,160 (25,514/ 32,646) | 6942 | (24.5) | 9127 | (23.6) |

| 1 or more | 24,004 (14,185/ 9819) | 5112 | (32.8) | 3908 | (33.8) |

| Missing | 5492 (2509/ 2983) | 650 | (22.3) | 826 | (21.4) |

| Living alone | |||||

| Yes | 72,576 (3604/ 7581) | 1844 | (46.3) | 2982 | (32.5) |

| No | 11,185 (37,005/ 35,571) | 10,205 | (25.0) | 9973 | (23.9) |

| Missing | 3895 (1599/ 2296) | 655 | (31.8) | 906 | (28.5) |

| Having spouse | |||||

| Yes | 65,850 (38,815/ 27,035) | 9741 | (24.7) | 7131 | (22.6) |

| No | 20,027 (2732/ 17,295) | 2620 | (41.0) | 6208 | (29.9) |

| Missing | 1779 (661/ 1118) | 343 | (35.0) | 522 | (28.6) |

| Frequency of going out | |||||

| > = 1/week | 82,904 (39,978/ 42,926) | 11,495 | (26.0) | 12,422 | (24.4) |

| < 1/week | 3521 (1650/ 1871) | 983 | (52.9) | 1159 | (51.4) |

| Missing | 1231 (580/ 651) | 226 | (30.3) | 280 | (27.8) |

| Participation in social groups | |||||

| Any participation | 35,105 (15,300/ 19,805) | 2906 | (17.3) | 4043 | (17.4) |

| No participation | 41,247 (21,982/ 19,265) | 8011 | (33.4) | 7289 | (33.1) |

| Missing | 11,304 (4926/ 6378) | 1787 | (29.9) | 2529 | (28.8) |

| Individual social cohesion | |||||

| Cohesive | 74,739 (36,331/ 38,408) | 9459 | (50.4) | 10,065 | (46.4) |

| Not cohesive | 11,814 (5454/ 6360) | 2982 | (23.7) | 3392 | (22.2) |

| Missing | 1103 (423/ 680) | 263 | (28.2) | 404 | (27.2) |

| Individual social support | |||||

| Any support | 85,783 (41,044/ 44,739) | 11,929 | (26.4) | 13,379 | (25.3) |

| No support | 1177 (818/ 359) | 566 | (65.2) | 266 | (66.8) |

| Missing | 696 (346/ 350) | 209 | (27.1) | 216 | (26.3) |

| Community-level social capital (unstandardized valuea) | |||||

| Community civic participation | 0.84 [0.17] (0.85 [0.17]/ 0.84 [0.18]) | ||||

| Community social cohesion | 2.01 [0.15] (2.01 [0.15]/ 2.01 [0.15]) | ||||

| Community reciprocity | 2.82 [0.05] (2.82 [0.05]/ 2.82 [0.05]) | ||||

These values were standardized in the later analysis.

Results of the Poisson regression showed that even after adjusting for age, educational attainment, marital status, living arrangement, the presence of comorbidities, frequency of going out, and the dummy variables representing the municipality or residence, low income was associated with the high prevalence of depressive symptoms. The adjusted prevalence ratio (PR) of depressive symptoms in the low-income group among men compared to the high-income group was 1.89 (95% confidence intervals [CI]: 1.80, 1.98), and the adjusted PR was 1.49 (95% CI: 1.42, 1.57) for the middle-income group (Model 2 in Table 2). Among women, the PR of depressive symptoms in the low-income group was 1.65 (95% CI: 1.57, 1.73) and 1.35 (95% CI: 1.27, 1.42) in the middle-income group compared to the high-income group. All community social capital components tended to be inversely associated with depressive symptoms. The adjusted PR per 1 standard deviation (SD) unit increase in community civic participation was 0.99 (95% CI: 0.97, 1.01) among men and 1.00 (95% CI: 0.97, 1.02) among women (Table 2). The adjusted PR per 1 SD unit increase in community social cohesion was 0.98 (95% CI: 0.96, 1.00) among men and 0.97 (95% CI: 0.95, 1.00) among women (Table 3). The adjusted PR per 1 SD unit increase in community reciprocity was 0.98 (95% CI: 0.96, 1.00) among men and 0.98 (95%CI: 0.96, 1.00) among women (Table 4).

Table 2.

Prevalence ratio (95% confidence intervals [CI]) for depressive symptoms: results of multilevel Poisson regression analysis modeling community civic participation.

| Men (n = 42,208) |

Women (n = 45,448) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null model | Model 1 Age-adjusted | Model 2 Multilevel | Model 3 Interaction added | Null model | Model 1 Age-adjusted | Model 2 Multilevel | Model 3 Interaction added | |

| PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | |

| Individual factors | ||||||||

| Intercept | 0.30 [0.29, 0.31] | – | 0.08 [0.06, 0.11] | 0.08 [0.06, 0.11] | 0.30 [0.29, 0.30] | – | 0.12 [0.09, 0.16] | 0.13 [0.10, 0.17] |

| Income (ref: T3 [High]) | ||||||||

| T1 (Low) | 2.24 [2.14, 2.35] | 1.89 [1.80, 1.98] | 1.81 [1.71, 1.93] | 1.95 [1.86, 2.05] | 1.65 [1.57, 1.73] | 1.50 [1.41, 1.61] | ||

| T2 (Middle) | 1.65 [1.57, 1.73] | 1.49 [1.42, 1.57] | 1.43 [1.34, 1.52] | 1.46 [1.38, 1.54] | 1.35 [1.27, 1.42] | 1.25 [1.16, 1.34] | ||

| Education ≤ 9 years (ref: >9 years) | 1.40 [1.35, 1.45] | 1.13 [1.09, 1.17] | 1.13 [1.09, 1.17] | 1.29 [1.24, 1.33] | 1.08 [1.04, 1.12] | 1.08 [1.04, 1.12] | ||

| Comorbidities: yes (ref: none) | 1.30 [1.26, 1.35] | 1.25 [1.20, 1.29] | 1.25 [1.20, 1.29] | 1.37 [1.32, 1.42] | 1.29 [1.24, 1.34] | 1.29 [1.24, 1.34] | ||

| Living alone (ref: no) | 1.84 [1.75, 1.93] | 1.42 [1.33, 1.53] | 1.42 [1.33, 1.53] | 1.34 [1.28, 1.39] | 1.23 [1.17, 1.29] | 1.23 [1.17, 1.29] | ||

| No spouse (ref: having spouse) | 1.63 [1.56, 1.70] | 1.20 [1.13, 1.28] | 1.20 [1.13, 1.28] | 1.24 [1.20, 1.29] | 1.07 [1.03, 1.12] | 1.07 [1.02, 1.11] | ||

| Freq. of going out < 1/week (ref: ≥1/week) | 1.94 [1.82, 2.08] | 1.52 [1.42, 1.63] | 1.53 [1.43, 1.63] | 1.88 [1.76, 2.00] | 1.56 [1.47, 1.67] | 1.57 [1.47, 1.67] | ||

| Participation in social groups (ref: no participation)a | 0.52 [0.50, 0.55] | 0.61 [0.58, 0.63] | 0.55 [0.50, 0.60] | 0.56 [0.54, 0.58] | 0.62 [0.59, 0.64] | 0.54 [0.50, 0.59] | ||

| Community-level factors | ||||||||

| Community civic participation (CP) (per 1SD increment) | 0.93 [0.91, 0.94] | 0.99 [0.97, 1.01] | 0.96 [0.92, 0.99] | 0.92 [0.90, 0.94] | 1.00 [0.97, 1.02] | 0.97 [0.93, 1.01] | ||

| Interaction terms | ||||||||

| Individual SC × income level (ref: T3 [High]) | ||||||||

| T1 (Low) | 1.14 [1.01, 1.27] | 1.26 [1.13, 1.40] | ||||||

| T2 (Middle) | 1.14 [1.01, 1.28] | 1.16 [1.03, 1.31] | ||||||

| Community CP x income level (ref: T3 [High]) | ||||||||

| T1 (Low) | 1.06 [1.01, 1.11] | 1.04 [0.99, 1.10] | ||||||

| T2 (Middle) | 1.02 [0.97, 1.08] | 1.05 [0.99, 1.11] | ||||||

| Variance components | ||||||||

| Residual district-level variance | 0.004 [0.002] | N/A | 2.43e−34 [4.31e−19] | 1.99e−34 [3.99e−19] | 0.014 [0.003] | N/A | 1.12e−34 [2.85e−19] | 2.71e−34 [5.07e−19] |

All models except for the null model are age-adjusted.

Missing values were taken into account in all variables including interaction terms.

Evaluated using the same questions for calculating the community civic participation score.

Table 3.

Prevalence ratio (95% confidence intervals [CI]) for depressive symptoms: results of multilevel Poisson regression analysis modeling community social cohesion.

| Men (n = 42,208) |

Women (n = 45,448) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null model | Model 1 Age-adjusted | Model 2 Multilevel | Model 3 Interaction added | Null model | Model 1 Age-adjusted | Model 2 Multilevel | Model 3 Interaction added | |

| PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | |

| Individual factors | ||||||||

| Intercept | 0.30 [0.29, 0.31] | 0.09 [0.07, 0.12] | 0.11 [0.08, 0.15] | 0.30 [0.29, 0.30] | 0.11 [0.09, 0.14] | 0.12 [0.09, 0.16] | ||

| Income (ref: T3 [High]) | ||||||||

| T1 (Low) | 2.24 [2.14, 2.35] | 1.88 [1.78, 1.97] | 1.44 [1.30, 1.60] | 1.95 [1.86, 2.05] | 1.65 [1.57, 1.73] | 1.44 [1.30, 1.60] | ||

| T2 (Middle) | 1.65 [1.57, 1.73] | 1.49 [1.42, 1.57] | 1.29 [1.15, 1.44] | 1.46 [1.38, 1.54] | 1.34 [1.27, 1.42] | 1.27 [1.13, 1.43] | ||

| Education < =9 year (ref: >9 year) | 1.40 [1.35, 1.45] | 1.17 [1.12, 1.21] | 1.17 [1.12, 1.21] | 1.29 [1.24, 1.33] | 1.12 [1.08, 1.16] | 1.12 [1.08, 1.16] | ||

| Comorbidities: yes (ref: none) | 1.30 [1.26, 1.35] | 1.25 [1.20, 1.29] | 1.25 [1.20, 1.29] | 1.37 [1.32, 1.42] | 1.30 [1.25, 1.35] | 1.30 [1.25, 1.35] | ||

| Living alone (ref: no) | 1.84 [1.75, 1.93] | 1.35 [1.25, 1.44] | 1.35 [1.25, 1.44] | 1.34 [1.28, 1.39] | 1.17 [1.11, 1.23] | 1.17 [1.12, 1.23] | ||

| No spouse (ref: having spouse) | 1.63 [1.56, 1.70] | 1.19 [1.12, 1.27] | 1.19 [1.12, 1.27] | 1.24 [1.20, 1.29] | 1.06 [1.02, 1.11] | 1.06 [1.02, 1.11] | ||

| Freq. of going out < 1/week (ref: >=1/week) | 1.94 [1.82, 2.08] | 1.54 [1.45, 1.65] | 1.55 [1.45, 1.66] | 1.88 [1.76, 2.00] | 1.59 [1.49, 1.70] | 1.60 [1.50, 1.70] | ||

| Individual social cohesion (SC)a (ref: not cohesive) | 0.47 [0.45, 0.49] | 0.56 [0.53, 0.58] | 0.45 [0.41, 0.49] | 0.48 [0.46, 0.50] | 0.54 [0.52, 0.57] | 0.49 [0.44, 0.54] | ||

| Community-level factors | ||||||||

| Community-level social cohesion (SC) (per 1SD increment) | 0.95 [0.93, 0.96] | 0.98 [0.96, 1.00] | 0.99 [0.95, 1.03] | 0.95 [0.94, 0.97] | 0.97 [0.95, 1.00] | 0.98 [0.94, 1.02] | ||

| Interaction term | ||||||||

| Individual SC × Income level (ref: T3 [High]) | ||||||||

| T1 (Low) | 1.40 [1.25, 1.57] | 1.19 [1.06, 1.34] | ||||||

| T2 (Middle) | 1.19 [1.05, 1.35] | 1.06 [0.93, 1.22] | ||||||

| Community SC x Income level (ref: T3 (High)) | ||||||||

| T1 (Low) | 0.98 [0.94, 1.03] | 0.99 [0.94, 1.04] | ||||||

| T2 (Middle) | 0.98 [0.93, 1.03] | 0.98 [0.93, 1.04] | ||||||

| Variance components | ||||||||

| Residual district-level variance | 0.004 [0.002] | N/A | 4.79e−35 [1.53e−19] | 4.11e−35 [1.71e−19] | 0.014 [0.003] | N/A | 6.24e−35 [2.02e−19] | 5.53e−35 [1.74e−19] |

All models except for the null model are age-adjusted.

Missing values were taken into account in all variables including interaction terms.

Evaluated using the same questions for calculating the community social cohesion score.

Table 4.

Prevalence ratio (95% confidence intervals [CI]) for depressive symptoms: results of multilevel Poisson regression analysis modeling community reciprocity.

| Men (n = 42,208) |

Women (n = 45,448) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null model | Model 1 Age-adjusted | Model 2 Multilevel | Model 3 Interaction added | Null model | Model 1 Age-adjusted | Model 2 Multilevel | Model 3 Interaction added | |

| PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | PR [95% CI] | |

| Individual factors | ||||||||

| Intercept | 0.30 [0.29, 0.31] | 0.10 [0.07, 0.13] | 0.13 [0.09, 0.19] | 0.30 [0.29, 0.30] | 0.14 [0.11, 0.19] | 0.21 [0.12, 0.35] | ||

| Income (ref: T3 [High]) | ||||||||

| T1 (Low) | 2.24 [2.14, 2.35] | 1.96 [1.86, 2.06] | 1.39 [1.03, 1.88] | 1.95 [1.86, 2.05] | 1.73 [1.64, 1.81] | 1.22 [0.75, 1.98] | ||

| T2 (Middle) | 1.65 [1.57, 1.73] | 1.52 [1.45, 1.60] | 1.20 [0.87, 1.65] | 1.46 [1.38, 1.54] | 1.37 [1.29, 1.44] | 1.00 [0.59, 1.71] | ||

| Education < =9 year (ref: >9 year) | 1.40 [1.35, 1.45] | 1.19 [1.14, 1.23] | 1.19 [1.14, 1.23] | 1.29 [1.24, 1.33] | 1.15 [1.11, 1.19] | 1.15 [1.11, 1.19] | ||

| Comorbidities: yes (ref: none) | 1.30 [1.26, 1.35] | 1.27 [1.22, 1.31] | 1.27 [1.22, 1.31] | 1.37 [1.32, 1.42] | 1.31 [1.26, 1.36] | 1.31 [1.26, 1.36] | ||

| Living alone (ref: no) | 1.84 [1.75, 1.93] | 1.35 [1.25, 1.45] | 1.35 [1.25, 1.45] | 1.34 [1.28, 1.39] | 1.18 [1.12, 1.24] | 1.18 [1.12, 1.24] | ||

| No spouse (ref: having spouse) | 1.63 [1.56, 1.70] | 1.21 [1.14, 1.28] | 1.21 [1.13, 1.28] | 1.24 [1.20, 1.29] | 1.08 [1.03, 1.12] | 1.08 [1.03, 1.13] | ||

| Freq. of going out < 1/week (ref: >=1/week) | 1.94 [1.82, 2.08] | 1.62 [1.51, 1.73] | 1.62 [1.52, 1.73] | 1.88 [1.76, 2.00] | 1.68 [1.58, 1.79] | 1.69 [1.58, 1.80] | ||

| Individual social support (ref: no support)a | 0.41 [0.38, 0.45] | 0.65 [0.60, 0.72] | 0.49 [0.37, 0.64] | 0.42 [0.37, 0.47] | 0.55 [0.49, 0.63] | 0.39 [0.25, 0.61] | ||

| Community-level factors | ||||||||

| Community reciprocity (per 1SD increment) | 0.95 [0.94, 0.97] | 0.98 [0.96, 1.00] | 0.99 [0.95, 1.03] | 0.96 [0.94, 0.97] | 0.98 [0.96, 1.00] | 0.99 [0.95, 1.03] | ||

| Interaction terms | ||||||||

| Individual social support × income level (ref: T3 [High]) | ||||||||

| T1 (Low) | 1.42 [1.05, 1.93] | 1.42 [0.87, 2.30] | ||||||

| T2 (Middle) | 1.27 [0.92, 1.76] | 1.37 [0.80, 2.34] | ||||||

| Community reciprocity x income level (ref: T3 [High]) | ||||||||

| T1 (Low) | 0.98 [0.94, 1.03] | 1.00 [0.95, 1.04] | ||||||

| T2 (Middle) | 0.99 [0.94, 1.04] | 0.99 [0.94, 1.05] | ||||||

| Variance components | ||||||||

| Residual district-level variance | 0.004 [0.002] | N/A | 6.91e−34 [2.06e−19] | 1.17e−34 [2.72e−19] | 0.014 [0.003] | N/A | 4.49e−34 [1.39e−19] | 9.34e−35 [2.29e−19] |

All models except for the null model are age-adjusted.

Missing values were taken into account in all variables including interaction terms.

Evaluated using the same questions for calculating the community reciprocity score.

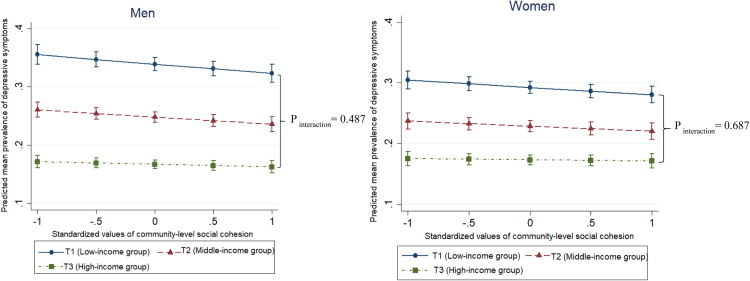

When we adjusted for covariates and cross-level interaction terms (Model 3 in Table 2), the association between low income and the high prevalence of depressive symptoms was stronger among those residing in the areas with high community-level civic participation (P = 0.016 in men, P = 0.080 in women, Fig. 1, Supplementary 1). The difference in predicted prevalence of depressive symptoms between the lowest- and highest-income groups was 17.4% points among men and 14.4% points among women where community-level civic participation was the mean level, while the difference was 18.8% points among men and 15.4% points among women where community-level civic participation was the + 1 SD level. We did not find statistically significant effect modification by the levels of community social cohesion or community reciprocity for the association between income and depressive symptoms (Table 3, Table 4). The decrement of difference in the predicted prevalence of depressive symptoms between the lowest- and highest-income groups was 0.8% points among men (P = 0.487) and 0.6% points among women (P = 0.687) per 1 SD unit increase in community-level social cohesion and 0.8% points among men (P = 0.482) and 0.4% points among women (P = 0.838) per 1 SD unit increase in community-level reciprocity (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Supplementary 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect modification by community civic participation levels on the association between income and depressive symptoms: predicted mean values of depressive symptoms (with 95% confidence intervals) by community civic participation across income tertiles. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals of predicted mean values of depressive symptoms. Pinteraction is the probability that the slope of low- and high-income groups in the prevalence of depressive symptoms across community civic participation levels would be the same as or more extreme than the actual observed results.

Fig. 2.

Effect modification by community social cohesion levels on the association between income and depressive symptoms: predicted mean values of depressive symptoms (with 95% confidence intervals) by community social cohesion across income tertiles. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals of predicted mean values of depressive symptoms. Pinteraction is the probability that the slope of low and high-income groups in the prevalence of depressive symptoms across community social cohesion levels would be the same as or more extreme than the actual observed results.

Fig. 3.

Effect modification by community social cohesion levels on the association between income and depressive symptoms: predicted mean values of depressive symptoms (with 95% confidence intervals) by community reciprocity across income tertiles. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals of predicted mean values of depressive symptoms. Pinteraction is the probability that the slope of low and high-income groups in the prevalence of depressive symptoms across community reciprocity levels would be the same as or more extreme than the actual observed results.

4. Discussion

The results of this study showed that the association between income and depressive symptoms varied across communities in relation to the levels of community social capital components, independent of community- and individual-level potential confounders and individual responses to social capital questions. Although the results suggest the overall preventive effect of community social capital on depressive symptoms, the effect size was small. The direction of the effect modification for the association between low income and high prevalence of depression differed by components; civic participation potentially strengthened the association, whereas social cohesion and community reciprocity did not modify the association.

Recent literature reviews showed that high community-level cognitive social capital is associated with a lower risk of developing common mental disorders (Ehsan and De Silva, 2015). The results of our study corresponded to this finding, showing the tendency of a smaller prevalence of depressive symptoms among residents of communities with richer social capital than among those living in communities with poorer social capital. However, in our study, the effect size was very small. Moreover, in contrast to the expectation, we could not detect a clear buffering effect of community-level social cohesion and reciprocity. Thus, our previous ecological observation might reflect not the contextual effect but the compositional effect of community-level social cohesion and reciprocity toward income-based inequality in depressive symptoms (Haseda et al., 2018). The results of the present study were not in line with another study based on JAGES, which suggests that neighborhood social cohesion could alleviate the negative effect of living alone (Honjo et al., 2018). This might happen because the gap of prevalence in depressive symptoms would be wider among different living arrangements than among different income groups, which could indicate the clear protective effect of community-level social cohesion.

Another literature review also suggests that a cohesive community environment might enforce a sense of solidarity among residents and serve as a barrier to discrimination and stigma toward socially vulnerable community members (i.e., ethnic minorities) (Pickett and Wilkinson, 2008). While the mental burden caused by loneliness (as a consequence of living alone) and discrimination could be directly buffered by community-level cognitive social capital (namely social cohesion and reciprocity), the financial burden (as reflected by a low-income status) might be affected more by the structural characteristics of the community, that is, the stronger physical and mental barriers to have new personal interactions and participation. To date, many studies have consistently shown that poorer individuals are less likely to participate in local activities (Mather, 1941, Marmot, 2002). As such, in our study, the multilevel models controlling for individual levels of community group participation suggest that community civic participation might actually increase the risk of depressive symptoms among the poor. That is, the benefit of community environments that promote group participation might not be effective for financially disadvantaged people in general. The possible mechanism of the deteriorating effect of community-level civic participation toward income-based inequality in depressive symptoms could be explained by both theoretical and empirical evidence. Social capital theorist Bourdieu conceptualizes that privileged people can easily exploit their capital of social connections (i.e., networks, by becoming members of groups) to reinforce their status (Bourdieu, 1984). Arneil and Offer also state that social pressure could exclude people of lower socioeconomic status, reflecting that the community context expressed by the high overall civic participation only benefits people in mainstream society, while the remaining people have few resources to develop opportunities (Arneil, 2006, Offer, 2012). In addition, Harpham et al. claim that group membership could damage mental health by imposing an extra burden or introducing stigma and peer pressure among vulnerable women (Harpham et al., 2006). Such a situation could produce negative feelings such as an inferiority complex in lower-income people, which could lead to the spread of depressive symptoms among them. The systematic review by Uphoff and Pickett, which reported that certain types of social capital might be beneficial only to those who had access to better health through their affluent assets, also supports our findings (Uphoff et al., 2013).

Although the overall trends in the findings were similar between men and women, as is indicated in another study (Vyncke et al., 2014), men showed potentially clearer results on the positive association between community civic participation and individual depressive symptoms and on the strengthening effects toward inequality in depressive symptoms. This might be because of a larger gap in the prevalence of depressive symptoms among income groups in men than women (Gero et al., 2017). Alternatively, mental stresses due to poverty may be stronger among older Japanese men. Saito et al. have reported that relative income deprivation increases the mortality risks more for men than for women among JAGES participants. Relative deprivation compared to others in their community might become a harmful psychosocial stressor for men (Saito et al., 2012).

This study has important policy implications. The Japanese government has officially recommended that local governments empower communities and community social capital to promote community health (Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare, 2015). Given the findings of this study, such efforts might decrease the prevalence of depressive symptoms in middle- or higher-income people. However, a conventional population approach that simply promotes opportunities for local group participation could widen the gap (Benach et al., 2013). Thus, continuous assessments of community intervention policies in terms of not only their overall effects but also their differential impacts on subpopulations should be conducted.

There are several limitations to this study. First, although this observational study suggests a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms among the poor in a community with rich civic participation, it cannot be inferred that actual interventions to promote community networking expand the socioeconomic gaps with regard to mental risks. For example, in the community intervention program in Taketoyo town, the municipal government strategically developed multiple voluntary social gathering programs called “ikoi-no-saron (recreation salon),” which halved the incidence of functional disabilities among its participants compared to non-participants. Importantly, the participants of the salon were primarily those whose incomes were low (Hikichi et al., 2015). Thus, a greater number of activities involving low-income people could alleviate inequality in depressive symptoms. Second, this cross-sectional study cannot account for temporal associations between community-level social capital and inequality in depressive symptoms. There can be two causal pathways between community social capital and depression. The former can affect not only individual mental health but also the depressed residents’ decisions on moving into or out of the community, potentially causing sample selection issues. Further studies using longitudinal data are required. Third, although we used a small area (i.e., school district) as the unit of community, because it was the smallest identifiable unit, we do not have strong support for the validity of utilizing this unit in evaluating community social capital. Hence, the risk of the modifiable area unit problem (MAUP) should be considered (Mobley et al., 2007). However, using the school district is correct in terms of the scale that we used to assess social capital, as the unit was exactly the same for developing the Health-Related Social Capital Scale (Saito et al., 2017). Fourth, there is a substantial amount of missing data. Given the general tendency of people with low-income levels and mental illnesses to avoid responding, the prevalence of depressive symptoms may be underestimated, potentially causing an underestimation of the relationships between income and depressive symptoms, which could in turn result in biasing the modification effects of community factors toward null. Fifth, the generalizability of this study to Japan as whole or to other countries may be limited as the participating municipalities are not nationally representative, though JAGES covers a wide variety of municipalities.

5. Conclusion

This cross-sectional research suggests that despite the potential overall benefits to decrease depressive symptoms, high levels of community civic participation may increase the income-based inequality in depressive symptoms. Policies aiming to build healthy communities should consider the potential positive and negative effects of community social capital (Portes, 1998). Universal activities promoting opportunities for civic participation might be insufficient in terms of building an equitable community, and it potentially expands the disparity in mental health. Such universal promotion should be coupled with additional targeted interventions toward populations with high isolation risks (Marmot et al., 2010).

Acknowledgments

This study used data from the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES), which was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grants (Numbers JP15H01972, JP20319338, JP22390400, JP23243070, JP23590786, JP23790710, JP24140701, JP24390469, JP24530698, JP24653150, JP24683018, JP25253052, JP25870573, JP25870881, JP2688201), Health Labour Sciences Research Grants (H28-Choju-Ippan-002, H26-Choju-Ippan-006, H25-Choju-Ippan-003, H25-Kenki-Wakate-015, H25-Irryo-Shitei-003[Fukkou, H24-Junkanki[Seishu]-Ippan-007), Research and Development Grants for Longevity Science from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Research Funding for Longevity Sciences from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (24-17, 24-23), Japan Foundation for Aging and Health (J09KF00804), and World Health Organization (WHO APW 2017/713981). The funding sources had no role in the design, execution, analysis, and interpretation of data or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.04.010.

Contributor Information

Maho Haseda, Email: hasedam@gmail.com.

Naoki Kondo, Email: naoki-kondo@umin.ac.jp.

Daisuke Takagi, Email: dtakagi-utokyo@umin.ac.jp.

Katsunori Kondo, Email: kkondo@chiba-u.jp.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- Arneil B. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. Diverse Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Benach J., Malmusi D., Yasui Y., Martínez J.M. A new typology of policies to tackle health inequalities and scenarios of impact based on Rose's population approach. J. Epidemiol. Community Heal. 2013;67:286–291. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L.F., Kawachi I., Glymour M.M. Second. ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2014. Social Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. [Google Scholar]

- Chang-Quan H., Zheng-Rong W., Yong-Hong L., Yi-Zhou X., Qing-Xiu L. Education and risk for late life depression: a meta-analysis of published literature. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2010;40:109–124. doi: 10.2190/PM.40.1.i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J., Shmotkin D., Hazan H. The effect of homebound status on older persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010;58:2358–2362. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M.G., Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2003;160:1147–1156. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehsan A.M., De Silva M.J. Social capital and common mental disorder: a systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2015;69:1021–1028. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-205868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M., Ng N., Weinehall L., Emmelin M. The importance of gender and conceptualization for understanding the association between collective social capital and health: a multilevel analysis from northern Sweden. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;73:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D.L., Charney D.S., Lewis L., Golden R.N., Gorman J.M., Krishnan K.R.R., Nemeroff C.B., Bremner J.D., Carney R.M., Coyne J.C., Delong M.R., Frasure-Smith N., Glassman A.H., Gold P.W., Grant I., Gwyther L., Ironson G., Johnson R.L., Kanner A.M., Katon W.J., Kaufmann P.G., Keefe F.J., Ketter T., Laughren T.P., Leserman J., Lyketsos C.G., McDonald W.M., McEwen B.S., Miller A.H., Musselman D., O’Connor C., Petitto J.M., Pollock B.G., Robinson R.G., Roose S.P., Rowland J., Sheline Y., Sheps D.S., Simon G., Spiegel D., Stunkard A., Sunderland T., Tibbits P., Valvo W.J. Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;58:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gero K., Kondo K., Kondo N., Shirai K., Kawachi I. Associations of relative deprivation and income rank with depressive symptoms among older adults in Japan. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017;189:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpham T., De Silva M.J., Tuan T. Maternal social capital and child health in Vietnam. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2006;60:865–871. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.044883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haseda M., Kondo N., Ashida T., Tani Y., Takagi D., Kondo K. Community social capital, built environment, and income-based inequality in depressive symptoms among older people in Japan: an ecological study from the JAGES project. J. Epidemiol. 2018;28:108–116. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20160216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikichi H., Kondo N., Kondo K., Aida J., Takeda T., Kawachi I. Effect of a community intervention programme promoting social interactions on functional disability prevention for older adults: propensity score matching and instrumental variable analyses, JAGES Taketoyo study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2015;69:905–910. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-205345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo K., Tani Y., Saito M., Sasaki Y., Kondo K., Kawachi I., Kondo N. Living alone or with others and depressive symptoms, and effect modification by residential social cohesion among older adults in Japan: the JAGES longitudinal study. J. Epidemiol. 2018 doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20170065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey S.L., Kealey M., Kurtovich E., Hunter R.H., Prohaska T.R., Bayles C.M., Satariano W.A. Neighborhood characteristics and depressive symptoms in an older population. Aging Ment. Health. 2015;19:713–722. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.962006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I., Kennedy B.P., Lochner K., Prothrow-Stith D. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am. J. Public Health. 1999;87:1491–1498. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.9.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo N., Kazama M., Suzuki K., Yamagata Z. Impact of mental health on daily living activities of Japanese elderly. Prev. Med. 2008;46:457–462. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. The influence of income on health: views of an epidemiologist. Health Aff. 2002;21:31–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M., Allen, J., Goldblatt, P., 2010. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010. The Marmot Review. London.

- Mather W.G. Income and social participation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1941;6:380–383. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare, 2015. Basic guidelines on the promotion of community health measures (in Japanese) [Online Document]. URL 〈http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10900000-Kenkoukyoku/0000079549.pdf〉. (Accessed 24 July 2017).

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, 2012. The second term of National Health Promotion Movement in the twenty first century (Health Japan 21 (the second term)).

- Mobley L.R., Kuo T.-M., Andrews L. How sensitive are multilevel regression findings to defined area of context?: a case study of mammography use in california. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2007;65:315–337. doi: 10.1177/1077558707312501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata C., Kondo K., Hirai H., Ichida Y., Ojima T. Association between depression and socio-economic status among community-dwelling elderly in Japan: the Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES) Health Place. 2008;14:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niino N., Imaizumi T., Kawakami N. A Japanese translation of the geriatric depression scale. Clin. Gerontol. 1991;10:85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nyunt M.S.Z., Fones C., Niti M., Ng T.-P. Criterion-based validity and reliability of the Geriatric Depression Screening Scale (GDS-15) in a large validation sample of community-living Asian older adults. Aging Ment. Health. 2009;13:376–382. doi: 10.1080/13607860902861027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offer S. The burden of reciprocity: processes of exclusion and withdrawal from personal networks among low-income families. Curr. Sociol. 2012;60:788–805. [Google Scholar]

- Pattyn E., Van Praag L., Verhaeghe M., Levecque K., Bracke P. The association between residential area characteristics and mental health outcomes among men and women in Belgium. Arch. Public Heal. 2011;69:3. doi: 10.1186/0778-7367-69-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett K.E., Wilkinson R.G. People like us: ethnic group density effects on health. Ethn. Health. 2008;13:321–334. doi: 10.1080/13557850701882928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998;24:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Saito M., Kondo N., Aida J., Kawachi I., Koyama S., Ojima T., Kondo K. Development of an instrument for community-level health related social capital among Japanese older people: the JAGES project. J. Epidemiol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.je.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M., Kondo N., Kondo K., Ojima T., Hirai H. Gender differences on the impacts of social exclusion on mortality among older Japanese: AGES cohort study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;75:940–945. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl S.T., Beach S.R., Musa D., Schulz R. Living alone and depression: the modifying role of the perceived neighborhood environment. Aging Ment. Health. 2016:1–7. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1191060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications . Japan Statistical Association; Tokyo: 2013. Statistical observations of Shi, Ku, Machi, Mura. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Uphoff E.P., Pickett K.E., Cabieses B., Small N., Wright J. A systematic review of the relationships between social capital and socioeconomic inequalities in health: a contribution to understanding the psychosocial pathway of health inequalities. Int. J. Equity Health. 2013;12:54. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyncke V., Hardyns W., Peersman W., Pauwels L., Groenewegen P., Willems S. How equal is the relationship between individual social capital and psychological distress? A gendered analysis using cross-sectional data from Ghent (Belgium) BMC Public Health. 2014;14:960. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T., Ishine M., Sakagami T., Okumiya K., Fujisawa M., Murakami S., Otsuka K., Yano S., Kita T., Matsubayashi K. Depression in Japanese community-dwelling elderly--prevalence and association with ADL and QOL. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2004;39:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waern M., Rubenowitz E., Wilhelmson K. Predictors of suicide in the old elderly. Gerontology. 2003;49:328–334. doi: 10.1159/000071715. (doi:71715) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Kobe: 2010. Urban HEART: Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool. [Google Scholar]

- Yan X.-Y., Huang S.-M., Huang C.-Q., Wu W.-H., Qin Y. Marital status and risk for late life depression: a meta-analysis of the published literature. J. Int. Med. Res. 2011;39:1142–1154. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage J.A., Sheikh J.I. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. 1986;5:165–173. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material