Significance

Maternal protein malnutrition during pregnancy and lactation compromises brain development, with lasting consequences for motor and cognitive function. However, the importance of nutrition on early brain development is unknown. We have previously shown that maternal low-protein diet confined to the preimplantation period (Emb-LPD) in mice, with normal nutrition thereafter, is sufficient to induce cardiometabolic and locomotor behavioral abnormalities in adult offspring. Here, we report that Emb-LPD and sustained LPD reduce neural stem cells (NSCs) in the fetal brain. Moreover, Emb-LPD causes remaining NSCs to upregulate neuronal differentiation in compensation beyond control levels and increase cortex thickness and neuron ratio, leading to adult memory deficits. These data demonstrate that poor maternal nutrition from conception adversely affects brain development and adult memory.

Keywords: DOHaD, neural stem cells, neurogenesis, low-protein diet, maternal diet

Abstract

Maternal protein malnutrition throughout pregnancy and lactation compromises brain development in late gestation and after birth, affecting structural, biochemical, and pathway dynamics with lasting consequences for motor and cognitive function. However, the importance of nutrition during the preimplantation period for brain development is unknown. We have previously shown that maternal low-protein diet (LPD) confined to the preimplantation period (Emb-LPD) in mice, with normal nutrition thereafter, is sufficient to induce cardiometabolic and locomotory behavioral abnormalities in adult offspring. Here, using a range of in vivo and in vitro techniques, we report that Emb-LPD and sustained LPD reduce neural stem cell (NSC) and progenitor cell numbers at E12.5, E14.5, and E17.5 through suppressed proliferation rates in both ganglionic eminences and cortex of the fetal brain. Moreover, Emb-LPD causes remaining NSCs to up-regulate the neuronal differentiation rate beyond control levels, whereas in LPD, apoptosis increases to possibly temper neuron formation. Furthermore, Emb-LPD adult offspring maintain the increase in neuron proportion in the cortex, display increased cortex thickness, and exhibit short-term memory deficit analyzed by the novel-object recognition assay. Last, we identify altered expression of fragile X family genes as a potential molecular mechanism for adverse programming of brain development. Collectively, these data demonstrate that poor maternal nutrition from conception is sufficient to cause abnormal brain development and adult memory loss.

The concept that in utero environment may influence postnatal health and disease risk is now well recognized following the original epidemiological studies on diverse human populations showing low birth weight and early catch-up growth during infancy associated with increased chronic disease in adulthood (1, 2). Such programming consequences also included cognitive decline and other neurodevelopmental disorders (3, 4). The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) concept has been further supported from human famine datasets, particularly the Dutch Hunger Winter, demonstrating that cardiometabolic and neurological dysfunction associate with in utero maternal nutrient depravation during pregnancy (5).

Both human studies and animal models further demonstrate the particular vulnerability of the periconceptional period in DOHaD-related programming. For example, people who were conceived during the Dutch famine (rather than experienced it during later gestation) had increased risk of schizophrenia and depression together with poorer cognitive capacity in later life as well as cardiometabolic consequences (5). Our own mouse studies have shown that maternal isocaloric low-protein diet (LPD) fed exclusively during preimplantation development (Emb-LPD), with control diet thereafter and postnatally, was sufficient to induce cardiometabolic and behavioral abnormalities in adult offspring (6). Early embryo vulnerability to maternal dietary quality may represent a form of developmental plasticity to coordinate fetal growth and metabolism with prevailing maternal conditions, but if conditions change, maladaptation may have consequences for disease risk in adulthood (7).

Animal studies to date show that maternal malnutrition during pregnancy and lactation may affect diverse aspects of brain development associated with impaired physical and coordinated movement, hyperactivity, altered social activity and motivation, as well as reduced mental and cognitive function, sometimes in a sex-specific manner (8–10). These consequences may derive from specific detriments on the maturation and functioning of brain tissues, such as the hippocampus, cortex, and hypothalamus affecting neurotransmitter and hormonal release (11–13). Maternal protein restriction may also affect the proliferation and differentiation capacities of neural stem cells (NSCs) (14). However, the consequences of maternal protein restriction (specifically during early embryonic development) on later brain development are unknown.

Here, we compare the effects of maternal Emb-LPD and sustained LPD on mouse brain development and the consequences in adult offspring, and show that NSC proliferation and maintenance are adversely affected by both treatments, leading to altered rates of neuronal differentiation. Our study shows maternal dietary quality from conception to be a critical factor in brain developmental capacity, with enduring consequences on brain organization and adult behavior.

Results

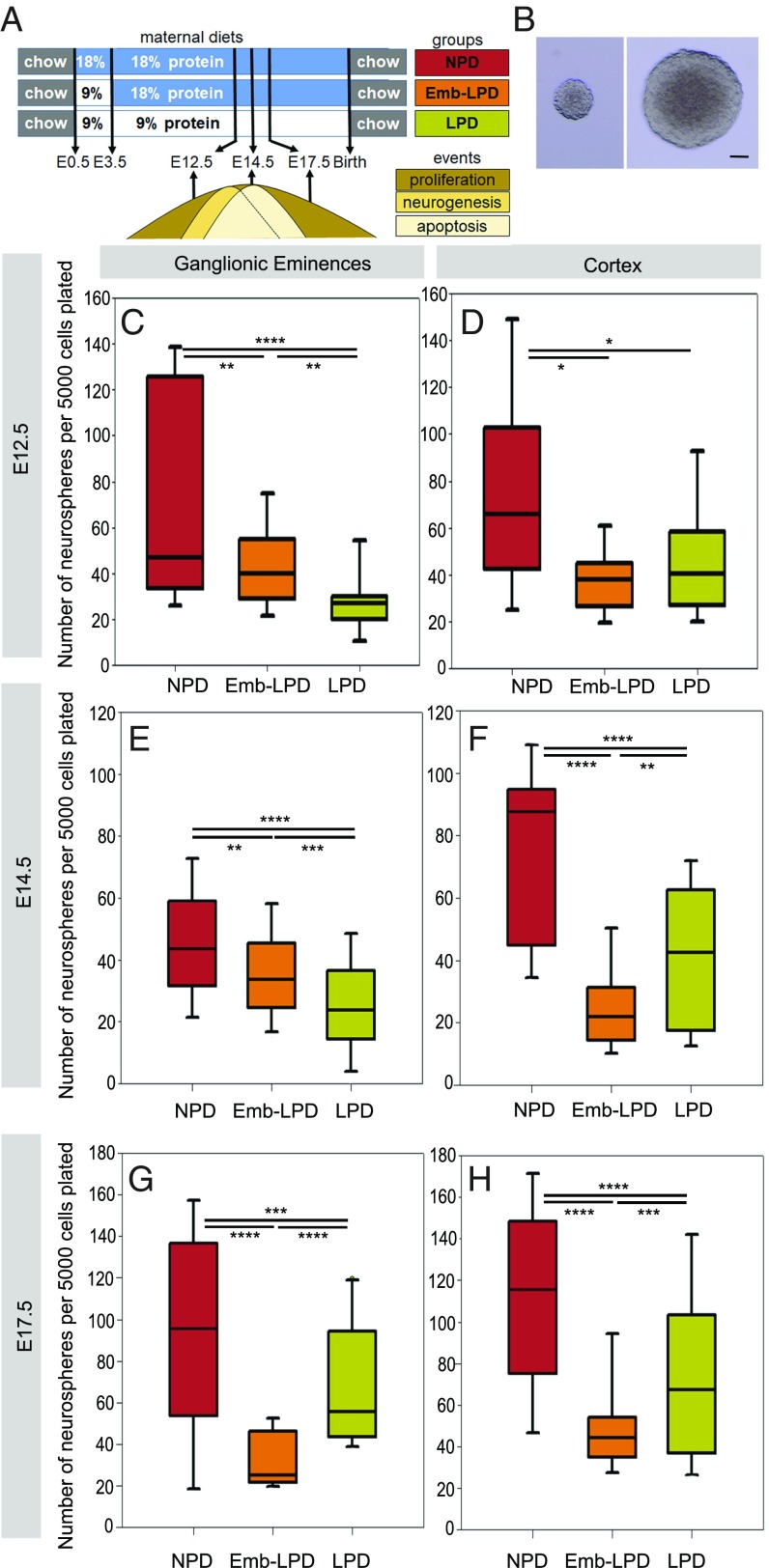

Maternal Protein Restriction Reduces Primary Sphere Formation from E12.5, E14.5, and E17.5 Ganglionic Eminences and Cortex Cells.

We first investigated the effect of maternal LPD (Fig. 1A and Table 1) on neurosphere formation (Fig. 1B), a measure of NSCs and early progenitor potential, from ganglionic eminence and cortex primary cells, at time points around the neurogenesis peak (E12.5 to E14.5) in these regions. We observed a significant decrease in the number of neurospheres formed after 7 d in culture, for both LPD and Emb-LPD, compared with normal-protein diet (NPD) at E12.5 (Fig. 1 C and D), E14.5 (Fig. 1 E and F), and E17.5 (Fig. 1 G and H), with a further significant decrease for LPD compared with Emb-LPD in E12.5 ganglionic eminences (Fig. 1C) and E14.5 ganglionic eminences and cortex cells (Fig. 1 E and F). At E17.5, both the ganglionic eminences and cortex cells from the Emb-LPD group formed significantly fewer neurospheres than both NPD and LPD (Fig. 1 G and H). These results were independent of maternal litter size (multilevel random-effects regression model analysis), the sex of the fetuses (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), and their position in the uterus. To assess the self-renewal capacity of the neurosphere cells, the primary neurospheres were passaged to give rise to secondary spheres (14-d total culture period from brain dissection). There was no difference in the number of secondary spheres formed from primary neurosphere cells after dissociation (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). These results reveal that maternal LPD and Emb-LPD caused reduced neurosphere-forming capabilities from ganglionic eminences and cortex primary cells at three fetal ages. This defect is rescued when the cells are passaged and is not present in secondary sphere formation. This suggests that the effect of maternal diet on cell potential does not persist with extended cell culture in vitro.

Fig. 1.

Maternal diet affects primary sphere formation from neural cells. (A) Experimental model describing the three diet groups, with NPD group exposed to 18% protein diet throughout gestation; LPD group exposed to 9% protein diet from vaginal plug on E0.5; and Emb-LPD group exposed to 9% protein diet between E0.5 and E3.5, followed by 18% protein diet until time of analysis at E12.5, E14.5, or E17.5. For adult offspring, dams were switched to RM1 chow at birth and offspring were given RM1 from weaning. Key events of cortex and ganglionic eminences development relevant to our study are highlighted, with NSC proliferation spanning the fetal time points of the present analysis, neurogenesis peaking between E12.5 and E14.5, and young neuron apoptosis peaking at E14.5. (B) Representative images of spheres generated from neural cells. (Scale bar, 50 µm.) (C–H) Quantification of the number of primary spheres (>100 µm in diameter) per well after 7 d, with 5,000 cells plated from the ganglionic eminences (C, E, and G) or cortex (D, F, and H) from the three maternal diet groups. E12.5 ganglionic eminences and cortex data represent n = 24 (NPD), 18 (Emb-LPD), and 21 (LPD) fetuses from eight (NPD), six (Emb-LPD), and seven (LPD) mothers. E14.5 ganglionic eminences data represent n = 131 (NPD), 125 (Emb-LPD), 124 (LPD) fetuses from 17 (NPD), 17 (Emb-LPD), and 18 (LPD) mothers. E14.5 cortex data represent n = 18 (NPD), 18 (Emb-LPD), and 19 (LPD) fetuses from six (NPD), six (Emb-LPD), and six (LPD) mothers. E17.5 ganglionic eminences data represent n = 18 (NPD), 18 (Emb-LPD), and 21 (LPD) fetuses from six (NPD), six (Emb-LPD), and seven (LPD) mothers, respectively. E17.5 cortex data represent n = 18 (NPD), 18 (Emb-LPD), and 24 (LPD) fetuses from six (NPD), six (Emb-LPD), and eight (LPD) mothers. Boxes represent interquartile ranges, with middle lines representing the medians; whiskers (error bars) above and below the box indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Table 1.

Composition of normal diet and LPD

| Component | NPD (18% protein), g/kg | LPD (9% protein), g/kg |

| Casein | 180 | 90 |

| Corn starch | 425 | 485 |

| Sucrose | 213 | 243 |

| Corn oil | 100 | 100 |

| Fiber | 50 | 50 |

| AIN-76-mineral mix | 20 | 20 |

| AIN-76-vitamin mix | 5 | 5 |

| DL-methionine | 5 | 5 |

| Choline chloride | 2 | 2 |

Maternal Protein Restriction Alters the Neuronal Differentiation Pathway in Ganglionic Eminences and Cortex in Vivo.

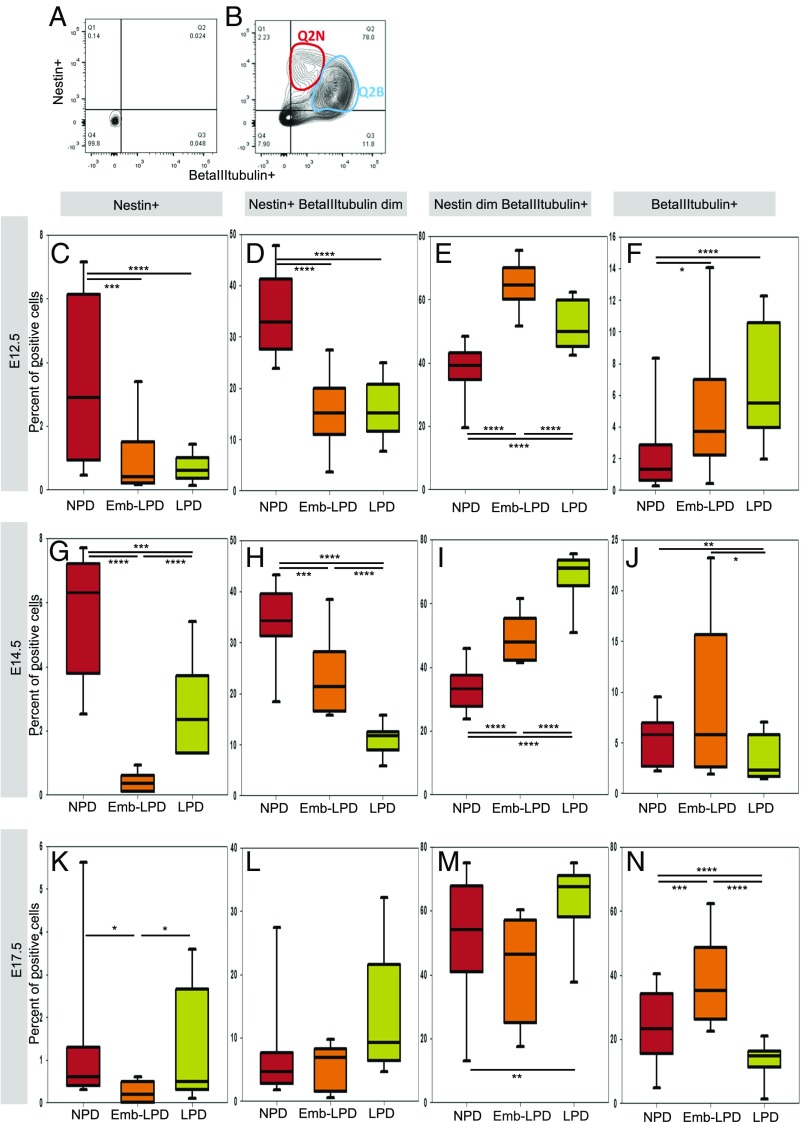

To assess whether the stemness and differentiation status of neural cells was affected by different maternal diets, ganglionic eminences and cortex primary cells were stained for Nestin and beta-III-tubulin and flow-cytometry sorted. The analyzed cells separated into four main populations: Nestin+-only (Q1, representing NSCs/progenitor cells), double-positive cells (Q2, representing neuronal progenitors), beta-III-tubulin+-only (Q4, representing differentiated neurons), and double-negative cells (Q3), compared with isotype control-stained cells (Fig. 2 A and B). When closely analyzing the FACS plots (Fig. 2B), two different populations could be detected in the double-positive cell population. These were separated as Nestin+ beta-III-tubulin dim (representing early neuronal progenitors, Q2N) and Nestin dim beta-III-tubulin+ (representing late neuronal progenitors, Q2B), where dim represents a moderately bright signal compared with the other cell populations (determined by cell density in Fig. 2B rather than arbitrary gating).

Fig. 2.

Maternal diet affects expression of neural stem cells and neuronal differentiation markers analyzed by flow cytometry in ganglionic eminences cells. Example of FACS plots with isotype control antibodies (A) and antibodies against Nestin and beta-III-tubulin (B), showing how ganglionic eminences cells were defined and gated: Nestin-only positive cells (Q1), double-positive cells (Q2), and beta-III-tubulin–only positive cells (Q4). Double-positive cells (Q2) were further separated into Nestin+ beta-III-tubulin dim (Q2N) and Nestin dim beta-III-tubulin+ (Q2B). A total of 10,000 cells were analyzed per sample. (C–K) Quantification by flow cytometry of E12.5 (C–F), E14.5 (G–J), and E17.5 (K–N) ganglionic eminences cells stained for Nestin and beta-III-tubulin. Nestin-only positive cells (C, G, and K), double-positive cells separated into Nestin+ beta-III-tubulin dim (D, H, and L) and Nestin dim beta-III-tubulin+ (E, I, and M), and beta-III-tubulin–only positive cells (F, J, and N) were quantified. E12.5 ganglionic eminences data represent n = 24 (NPD), 18 (Emb-LPD), and 21 (LPD) fetuses from eight (NPD), six (Emb-LPD), and seven (LPD) mothers. E14.5 ganglionic eminences data represent n = 131 (NPD), 125 (Emb-LPD), and 124 (LPD) fetuses from 17 (NPD), 17 (Emb-LPD), and 18 (LPD) mothers. E17.5 ganglionic eminences data represent n = 18 (NPD), 18 (Emb-LPD), and 18 (LPD) fetuses from six (NPD), six (Emb-LPD), and six (LPD) mothers. Boxes represent interquartile ranges, with middle lines representing the medians; whiskers (error bars) above and below the box indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Nestin-only positive cells represented only a small percentage of the whole population and, in ganglionic eminences (Fig. 2) and cortex (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) cells, showed a significant decrease in Emb-LPD at E12.5, E14.5, and E17.5, as well as in LPD at E12.5 and E14.5, whereas E17.5 LPD Nestin+-only cells did not differ from NPD (Fig. 2 C, G, and K and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A, E, and I). The decrease in Nestin+-only cells confirms the decrease in sphere-forming cells observed in the sphere assay and suggests a decrease in NSCs at E12.5 and E14.5 in both Emb-LPD and LPD and at E17.5 in Emb-LPD.

Nestin+ beta-III-tubulin+ cells represented the majority of cells, illustrating the fact that most of the cells were in transition between undifferentiated and neuronally differentiated cells. When analyzed separately, the two neuronal progenitor populations showed very different results in both ganglionic eminences and cortex at E12.5 and E14.5: the early neuronal progenitors decreased significantly in both Emb-LPD and LPD compared with NPD (Fig. 2 D and H and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and F), whereas the late neuronal progenitors increased significantly in both Emb-LPD and LPD compared with NPD (Fig. 2 E and I and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 C and G). At E17.5, the proportion of both early and late neuronal progenitors in Emb-LPD and early progenitors in LPD was unchanged compared with NPD (Fig. 2 L and M and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 J and K), whereas the LPD late progenitor proportion was increased (Fig. 2M and SI Appendix, Fig. S2K). Beta-III-tubulin–only positive cells represent differentiated neurons and showed a significant increase in Emb-LPD E12.5 and E17.5 in both ganglionic eminences and cortex (Fig. 2 F and N and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 D and L), with no difference at E14.5 (Fig. 2J and SI Appendix, Fig. S2H). In LPD, the beta-III-tubulin+ cell proportion was significantly increased at E12.5, whereas it was significantly decreased at E14.5 and E17.5 in both ganglionic eminences and cortex (Fig. 2 F, J, and N and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 D, H, and L). Offspring sex effects were not found with statistical analysis in the FACS data at any time point, with 40 to 50% of the data generated from female offspring.

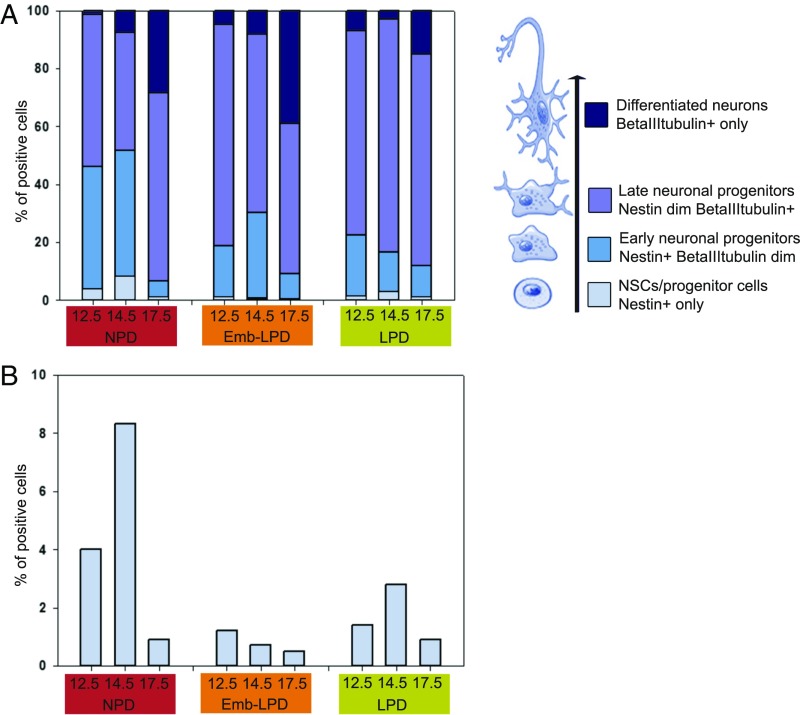

These detailed FACS analyses are schematically summarized for ganglionic eminences primary cells (Fig. 3A), with enlargement of the Nestin+-only cells data (Fig. 3B, light blue). This shows clearly that the proportion of Nestin+-only cells peaks at E14.5 compared with E12.5 and E17.5 in NPD. LPD Nestin+-only cell proportions follow the same pattern across time, although at reduced levels at E12.5 and E14.5, whereas the Emb-LPD Nestin+-only cell proportions are low from E12.5 and continuously decrease until E17.5 (Fig. 3B). Early progenitor (royal blue, Nestin+ beta-III-tubulin dim cells) proportions decrease at E12.5 and E14.5 in both LPD and Emb-LPD compared with NPD. Late progenitor (purple, Nestin dim beta-III-tubulin+ cells) proportions increase in Emb-LPD and LPD at both E12.5 and E14.5 as well as in LPD at E17.5, compared with NPD. Differentiated neuron (dark blue, beta-III-tubulin+-only cells) proportions increase at E12.5 for both Emb-LPD and LPD, as well as at E17.5 for Emb-LPD, whereas they decrease in LPD at both E14.5 and E17.5, compared with NPD. Collectively, in Emb-LPD, there is a reduction in NSCs and an increase in differentiated neurons over time compared with NPD. In LPD, a reduction in NSCs is also evident, but differentiated neuron formation becomes stabilized over time, more similar to NPD.

Fig. 3.

Summary of flow cytometry data for ganglionic eminences primary cells. (A) Summary of the FACS data at E12.5, E14.5, and E17.5 for ganglionic eminences primary cells from Fig. 2 C–N, with enlargement of the neural stem/progenitor cells data shown in B (Nestin+, light blue). Early neuronal progenitors (Nestin+ beta-III-tubulin dim, royal blue), late neuronal progenitors (Nestin dim beta-III-tubulin+, purple), and neurons (beta-III-tubulin+, dark blue) are presented along the differentiation lineage at Right (black arrow).

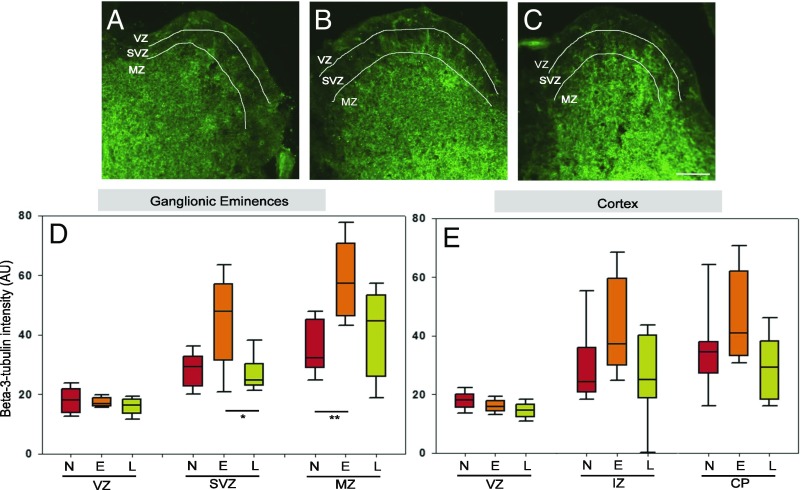

To confirm these results and to resolve any regional variation within ganglionic eminences and cortex, coronal brain sections were stained for a marker of NSCs (Sox2) and a marker of neural progenitors and young neurons (beta-III-tubulin). Sox2 was chosen, instead of Nestin used in the FACS experiments, because it labels NSCs but not progenitor cells. Staining was quantified in ganglionic eminences ventricular zone (VZ), subventricular zone (SVZ), and mantle zone (MZ), and in cortex in VZ, intermediate zone (IZ), and cortical plate (CP), when relevant. Sox2 staining was present in both the ganglionic eminences and cortex, mostly in the VZ and SVZ/IZ where NSCs reside. Quantification revealed a significant decrease of the number of positive cells in LPD compared with NPD, in the ganglionic eminences VZ at E12.5 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A), with a similar trend in the cortex VZ at the same age (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B), as well as in both regions at E14.5 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D). A similar decreasing trend is noticed in the Emb-LPD group at E12.5 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B) and E14.5 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D). No change is observed at E17.5 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 E and F) in both diet groups and regions, compared with NPD. The decrease in proportion of Sox2+ cells observed here confirms the decrease in NSCs/progenitor cells, seen in the sphere assay and FACS analysis.

Beta-III-tubulin staining was light in VZ of ganglionic eminences, stronger in SVZ, and even more in the MZ (Fig. 4 A–C). Its quantification showed an increase in Emb-LPD SVZ and MZ in ganglionic eminences at E14.5 (Fig. 4D) and a comparable trend in the cortex at E14.5 (Fig. 4E, P = 0.0724 in IZ and P = 0.0586 in CP), compared with both NPD and LPD. No difference was found in the VZ (Fig. 4 D and E), as expected, because this layer contains mostly undifferentiated cells and very few differentiated neurons. This increase confirms the FACS analysis in which collectively, the three cell categories positive for beta-III-tubulin are increased in Emb-LPD at E14.5 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Maternal diet affects expression of neuronal differentiation markers analyzed by immunohistochemistry in E14.5 ganglionic eminences and cortex. (A–C) Representative images illustrate the staining results quantified: beta-III-tubulin (green) stained on E14.5 ganglionic eminences sections from maternal NPD (A), Emb-LPD (B), and LPD (C). (Scale bar, 150 µm.) (D and E) Quantification of beta-III-tubulin staining (percentage of positive pixels per area) on E14.5 ganglionic eminences (D) and cortex (E) sections from different maternal diets. Data represent three quantifications per layer per section of three sections per brain, from nine fetal brains from nine different mothers per diet. Boxes represent interquartile ranges, with middle lines representing the medians; whiskers (error bars) above and below the box indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. E, Emb-LPD; L, LPD; N, NPD.

Collectively, these results indicate that maternal diet not only affects the availability of NSCs in the VZ but also their pattern of differentiation toward a neuronal fate in the layers containing more differentiated cells (SVZ and MZ for ganglionic eminences; IZ and CP for cortex). Thus, in Emb-LPD, there is a decrease in NSCs/progenitor cells and an increase in late neuronal progenitors and neurons. In contrast, LPD induces a decrease in NSCs/progenitor cells and an increase in late neuronal progenitors, but is not followed by an increase in neurons.

Maternal Protein Restriction Reduces Proliferation of Ganglionic Eminences and Cortex Cells.

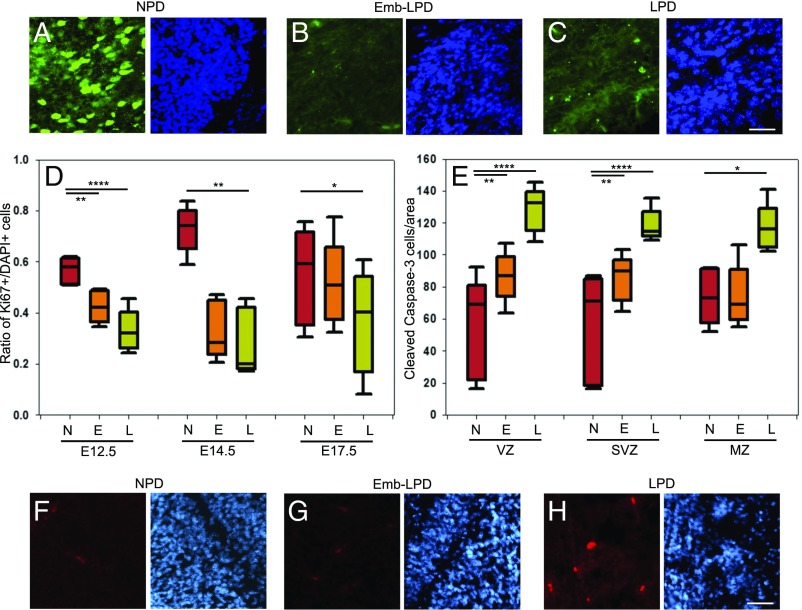

NSCs need to proliferate to maintain and/or increase their population in vivo and to form neurospheres in vitro. A defect in proliferation might account for the apparent loss of NSCs seen following Emb-LPD and LPD in the neurosphere assay and the FACS and immunohistochemical analyses. The growth fraction (Ki67+/DAPI+) was analyzed in the VZ of both cortex and ganglionic eminence coronal sections (Fig. 5 A–C). The growth fraction significantly decreased for both Emb-LPD and LPD compared with NPD, at E12.5, E14.5, and E17.5 (Fig. 5D and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). These results were confirmed by analyzing the proliferation of plated cells from E14.5 ganglionic eminences using Ki67 and BrdU as markers of proliferating cells and cells in S phase, respectively. Growth fraction and mitotic index were calculated as the proportion of DAPI-labeled cells stained with Ki67 and with BrdU, respectively, while the labeling index was calculated as the proportion of Ki67-labeled cells stained with BrdU. A significant decrease of all three proliferation indices was present in LPD compared with NPD and in the mitotic and labeling indices for Emb-LPD (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 C–E). Thus, maternal Emb-LPD and LPD reduce the proliferation of ganglionic eminences and cortex cells in the VZ where most NSCs are located, thereby potentially contributing to the loss of NSCs reported above.

Fig. 5.

Maternal diet affects proliferation and apoptosis in ganglionic eminences. (A–C) Representative images illustrate the staining results quantified in D: Ki67 (green) and DAPI (blue) are stained on E12.5 ganglionic eminences sections from maternal NPD (A), Emb-LPD (B), and LPD (C). (Scale bar, 50 µm.) (D) The growth fraction quantifies the proportion of cells (DAPI+) which are proliferating (Ki67+) in E12.5, E14.5, and E17.5 ganglionic eminences VZ sections. Data represent three quantifications per layer per brain of three sections per brain of five fetal brains, from five different mothers per diet. (E) Quantification of cleaved caspase-3 staining (number of positive cells per area) on E17.5 ganglionic eminences sections. Data represent three quantifications per layer per brain of three sections per brain of five fetal brains, from five different mothers per diet. Boxes represent interquartile ranges, with middle lines representing the medians; whiskers (error bars) above and below the box indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. (F–H) Representative images illustrate the staining results quantified in E: cleaved caspase-3 (red) and DAPI (blue) staining of E17.5 ganglionic eminences SVZ sections from maternal NPD (F), Emb-LPD (G), and LPD (H). (Scale bar, 50 µm.) E, Emb-LPD; L, LPD; N, NPD.

Maternal Protein Restriction Increases Apoptosis of Ganglionic Eminences and Cortex Cells.

Cell death through apoptosis is another mechanism by which cell numbers might be regulated, and we thus analyzed apoptosis by immunostaining for activated cleaved caspase-3 on coronal sections (Fig. 5 F–H). Quantification of the number of positive cells per area revealed that apoptotic cell numbers significantly increased in LPD in all three layers of the ganglionic eminences (Fig. 5E) and cortex (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B) at E17.5. It was also significantly increased in Emb-LPD VZ and SVZ/IZ at E17.5 (Fig. 5E and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). However, there was no difference in both Emb-LPD and LPD at both E12.5 and E14.5, compared with NPD. This increase in apoptosis at E17.5 in LPD may further explain why the increased proportion of late neuronal progenitors does not lead to a proportionate increase in neurons formed.

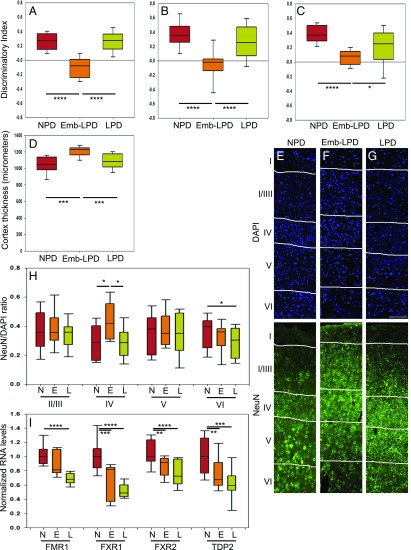

Maternal Protein Restriction Induces Adult Offspring Short-Term Memory Defects and Permanently Alters Neuronal Ratio in Adult Cortex.

To see if the alterations at fetal stages persist into adulthood and cause behavioral phenotype, adult offspring were subjected to behavioral tests. Novel-object recognition tests were performed at 41 d (Fig. 6A), 64 d (Fig. 6B), and 96 d (Fig. 6C) after birth to test short-term memory. Our results show that the Emb-LPD group performed significantly worse at all three time points, compared with the NPD group, with a discrimination index between novel and familiar object close to 0, showing no greater time spent to explore the novel object. The LPD group showed no difference with the NPD group. There was no difference in anxiety shown by the elevated-plus maze tests among the groups for both sexes. At time of death, weights were taken, and offspring male and female body weights and brain weight/body weight ratios were significantly different for Emb-LPD compared with NPD groups (Table 2), with no significance for LPD compared with NPD. To see if the fetal brain cytoarchitecture changes persisted in the adult and correlated with the behavior phenotype, the cortex of adult offspring was analyzed for cortex thickness, neuron ratio, and gene expression. Our data show that somatosensory cortex thickness is significantly increased in the Emb-LPD group compared with both NPD and LPD groups (Fig. 6D). To explore neuronal density, cortex was stained for NeuN, a mature neuron marker (Fig. 6 E–G), and positive cells were counted and compared with total cell numbers. Our data show that the neuronal density NeuN+/DAPI+ is significantly increased in layer IV, in Emb-LPD compared with NPD mice (Fig. 6H). The LPD group shows significant neuronal density decrease in layer VI compared with the NPD group. Our data show that the increased neuronal ratio observed at fetal stage persists in the adult cortex and relates to the short-term memory defects in the Emb-LPD group, compared with both NPD and LPD groups.

Fig. 6.

Maternal diet affects adult offspring short-term memory, cortical neuron ratio, and fragile X genes RNA levels. (A–C) Discrimination index of familiar versus novel objects during the novel-object recognition test at 41 d (A), 64 d (B), and 96 d (C). Data for exploration time for the novel object (Tn) versus the familiar object (Tf) are presented as the discrimination index: (Tn-Tf)/(Tn+Tf). Data collected from 14 to 22 animals from three to four mothers per group. (D) Quantification of somatosensory cortex thickness in micrometers on adult brain sections in cortical layers I to VI. Data represent one quantification per brain of three sections per brain of 10 brains, from five different mothers per diet. (E–G) Representative images illustrate the staining results quantified in H: NeuN (green) and DAPI (blue) are stained on adult female somatosensory cortical sections spanning layers I to VI, from maternal NPD (E), Emb-LPD (F), and LPD (G). (Scale bar, 100 µm.) (H) Quantification of neuron ratio (ratio of NeuN-positive cells versus DAPI-positive cells) on adult somatosensory cortex sections in layers II/III to VI. Data represent three quantifications per layer per brain of three sections per brain of 10 brains, from five different mothers per group. (I) Quantification of Fmr1, Fxr1, Fxr2, and Tdp2 RNA levels by qRT-PCR, normalized to housekeeping genes Ap3d1 and Gapdh. Data represent one sample per brain of 12 to 19 brains from three or four different mothers per group. Both male and female adult offspring were analyzed. Offspring sex effects were not found using our multilevel linear regression model; thus, representation of our data includes both males and females in balanced ratio. Boxes in A–D, H, and I represent interquartile ranges, with middle lines representing the medians; whiskers (error bars) above and below the box indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. E, Emb-LPD; L, LPD; N, NPD.

Table 2.

Weights of female and male offspring at time of death

| Offspring | Parameter | NPD | Emb-LPD | LPD | |||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||

| Females | Body weight, g | 37.75 | 36.82–39.22 | 40.42* | 36.89–42.57 | 37.03 | 34.80–39.36 |

| Brain weight, g | 0.49 | 0.48–0.51 | 0.48 | 0.47–0.49 | 0.49 | 0.45–0.49 | |

| Brain weight/body weight ratio | 0.0130 | 0.0125–0.0136 | 0.0116* | 0.0112–0.0131 | 0.0132 | 0.0115–0.0139 | |

| Males | Body weight, g | 43.37+++ | 42.01–46.12 | 45.34*,+++ | 44.15–49.36 | 42.66+++ | 41.05–46.32 |

| Brain weight, g | 0.49 | 0.45–0.50 | 0.49 | 0.47–0.49 | 0.48 | 0.47–0.50 | |

| Brain weight/body weight ratio | 0.0117+ | 0.0107–0.0130 | 0.0102**,#,+++ | 0.0093–0.0109 | 0.0111+ | 0.0106–0.0119 | |

Significant differences were found between the groups for body weight for Emb-LPD vs. NPD (*P < 0.05), and the brain weight/body weight ratio for Emb-LPD vs. NPD (**P < 0.01) and vs. LPD in males (#P < 0.05). Significant effect of sex was also found for body weight and brain weight/body weight ratio (+P < 0.05; +++P < 0.001 comparing males vs. females), but not for brain weight (P > 0.05). No significant interaction between treatment and sex were found. Boldface highlights values different between groups (* and #), which are the important differences within the context of our study. The sex effect (+) is not novel but is reported for sake of completeness. IQR, interquartile range.

Maternal Protein Restriction Decreases Fragile X Gene Family RNA Levels in Adult Cortex.

Following some RNA sequencing analysis of related samples from our model, some candidate genes were selected to be tested in cortex samples. To explore possible molecular mechanisms responsible for the cellular and behavior changes, we performed qRT-PCR for genes known to be involved in cognitive functions (such as short-term memory) and that were shortlisted in our RNA sequencing analysis. Our data show that the RNA levels of fragile X mental retardation 1 (Fmr1), fragile X mental retardation autosomal homolog (Fxr)1 and Fxr2, and Tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterase 2 (Tdp2) are decreased in the LPD adult cortex compared with NPD group, with Fxr1, Fxr2, and Tdp2 also decreased in the Emb-LPD group (Fig. 6I). This relates to the behavior and cellular phenotype observed in the Emb-LPD animals, with an independent cellular compensatory mechanism taking place in the LPD group.

Discussion

We have shown, using in vivo and in vitro techniques, that Emb-LPD and sustained LPD reduce NSCs/progenitor cell numbers through suppressed proliferation rates in both ganglionic eminences and cortex of the fetal brain at three different time points. Moreover, we found that the diminished stem cell pool after dietary treatment exhibits distinct differentiation dynamics, with Emb-LPD inducing an increase in late neuronal progenitors and young neurons while LPD induced an increase in late neuronal progenitors, but not in young neurons. Our study, therefore, shows that maternal protein restriction, even during a very short and early period (Emb-LPD), leads to later effects on NSCs/progenitor cells, possibly due to a decrease in proliferation and an increase in apoptosis. However, for clarity, the timing of these effects during fetal development may not necessarily occur during preimplantation development but may derive subsequently up to the time of our fetal analyses.

Our data further indicate that compensatory processes are put in place to alleviate the effects of the stem cell deficit but vary according to diet treatment. Thus, while both LPD and Emb-LPD respond by increased progenitor neuronal differentiation, only in LPD is this potential excess of neurons tempered, possibly by the increased apoptosis observed, while in Emb-LPD, an overproduction of neurons occurs in a growth-promoting environment of nutrient availability (discussed below). This leads to an increased cortical neuron ratio in adulthood and associates with short-term memory defect and decreased RNA levels of fragile X gene family in adult cortex. Collectively, our results add insight to the growing literature on the impact of maternal undernutrition on the offspring brain: While later gestation and perinatal challenge induces defects in brain neurochemistry (9), including decreased dopamine or increased serotonin levels (11–13) together with behavioral and cognitive defects (8), our data show that diet challenge from conception can cause comprehensive change in brain structural development and neurogenesis, with enduring effects on behavior and memory.

How might the altered patterns of brain development reported here, and with distinct outcomes between Emb-LPD and LPD treatments, derive? Previously, we have shown that the early embryo before implantation may sense maternal Emb-LPD through deficient nutrient availability within uterine luminal fluid, leading to suppression of blastocyst mTORC1 signaling (15), a dietary-induced mechanism that may also function in the human (16). Blastocyst sensing of poor maternal nutrients activates compensatory responses within extraembryonic lineages, which collectively lead to the development of a more efficient placenta and yolk sac (6, 7, 17, 18). However, in contrast, early undifferentiated embryonic lineages, studied using embryonic stem cell lines derived from Emb-LPD and NPD blastocysts, exhibit reduced cellular survival, including reduced ERK-1/2 signaling and increased apoptosis (19), a phenotype consistent with the reduced NSC pool found in the Emb-LPD and LPD fetal brain and associated increase in detection of cellular apoptosis. A further characteristic of later embryonic lineages in fetal somatic tissues such as liver and kidney relates to differential growth rate, with continued LPD challenge suppressing ribosome biogenesis, and release from this challenge (as in Emb-LPD) stimulating ribosome biogenesis relative to NPD controls, thereby coordinating growth with nutrient availability (20).

Thus, within the context of the current study on brain development, we interpret the initial reduction in NSCs found in both Emb-LPD and LPD samples as a consequence of either adverse dietary programming of undifferentiated cells, although the mechanism of induction is currently unknown, or maternal carry-over effects. Subsequently, during fetal development, while both the Emb-LPD and LPD fetuses will be responsive to compensatory extraembryonic systems, only the Emb-LPD fetuses will be in a “catch-up” growth environment. Indeed, Emb-LPD offspring have increased mass during late gestation and postnatally compared with LPD and NPD offspring (6). Given these distinct characteristics, the Emb-LPD brain phenotype of reduced NSCs (but leading to stimulated neurogenesis across the E12.5 to E17.5 time course) and increased neuron ratio in the adult, compared with NPD, may reflect these systemic changes in programming environments. In contrast, the LPD brain, following NSC loss, will be within a more restrained growth environment, limiting the rate of neurogenesis.

Although these systemic factors may induce and contribute to the distinct embryonic programming mediated through maternal Emb-LPD and LPD, we need to further consider more specific factors that may influence fetal brain development. One candidate linking maternal LPD with offspring brain phenotype is docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). DHA concentration has been shown to be reduced in maternal liver and plasma after maternal LPD, leading to a specific impaired accumulation of DHA in the offspring fetal brain (21, 22). DHA has been shown to increase neurosphere formation (23), which is consistent with the decrease in neurosphere formation shown here with LPD and Emb-LPD. DHA has also been shown to increase neuronal differentiation (beta-III-tubulin and MAP-2 positive cells) by decreasing Hes1 and increasing p27, thus leading to a cell cycle arrest of the NSCs (24). Hes1 itself is important for NSC maintenance (25, 26). This was confirmed by others showing increase in beta-III-tubulin and MAP2 via activation of the PKA and CREB pathway (27). This might explain the effect of LPD on NSCs, but what about the Emb-LPD? Here, in the Emb-LPD group, the LPD stops at E3.5, a few days before the NSC population is formed. However, the half-life of DHA in the rat brain (several weeks) (28) suggests that this specific effect of diet treatment may be long lasting and potentially retained in Emb-LPD up to the time of in vivo analysis.

Apart from its effect on NSCs, we show here that both maternal LPD and Emb-LPD have an effect on neuronal differentiation. Indeed, both treatments decrease the proportion of early progenitors while increasing the proportion of late progenitors. These results could be explained by specific alteration to the expression of the markers Nestin and beta-III-tubulin. Indeed, either higher expression of beta-III-tubulin in early progenitors or higher expression of Nestin in late progenitors would have led to a higher proportion of late progenitors and a lower proportion of neurons, respectively. Such altered expression of Nestin has, for example, been observed in ischemic tissue damage (29) or following maternal restricted diet in the postnatal hippocampus (14). Alternatively, maternal LPD during fetal development (as opposed to Emb-LPD) induces inhibition of differentiation of late progenitors into neurons. This disconnection between progenitor and neuron numbers has been described before in other contexts, where an increase in progenitor cells is not fully translated into the generation of mature neurons after a calorie-restricted diet (30) or in hippocampal adult neurogenesis (31). In our model, the mechanism ensuring the elimination of excess neurons is conserved in LPD, whereas it is disturbed in Emb-LPD, leading to increased neurons in late gestation compared with controls. Our data suggest that an early event in embryo development still affects neurogenesis in later pregnancy (discussed above) and neuron ratio in adulthood. E14.5 is the time in cortex development at which 70% of the cells generated undergo programmed cell death (32), and our data suggest that LPD and Emb-LPD could affect this process in distinct ways, as also identified in undifferentiated embryonic stem cell lines (19).

We identified a decrease in the fragile X family genes RNA levels in Emb-LPD and LPD that coincides with our behavioral deficit and altered cellular phenotype in Emb-LPD, with an independent compensatory mechanism taking place in the LPD group to restore normal neuron proportion and behavior. FRM1P, FXR1P, and FXR2P are neuronal RNA-binding proteins involved in fragile X syndrome. They have the ability to interact and compensate each other, as Fmr1 and Fxr2 double-knockout mice display more severe neurobehavioral abnormalities compared with single-knockout mice (33). Fmr1 or Fxr2 knockout mice have memory and cognition defects (34–36), similar to our maternal protein restriction model. FRM1P is also associated with topoisomerase 3β (37, 38), which is itself a plausible substrate of TDP2 (39, 40) and associated with cognitive impairment (37, 41). We thus speculate that the decrease in fragile X family genes RNA levels highlights a molecular mechanism that could be responsible for our behavioral and cellular phenotype.

In conclusion, we find that maternal protein-restricted diet, even exclusively before embryo implantation, can alter the developmental program, leading to permanent deficits in the offspring brain such as reducing NSCs, altering the dynamics of neuronal differentiation, and associating with behavioral defects. As discussed, our data strengthen the existing literature on early embryo sensing of dietary quality, with understanding on the adverse consequences on fetal brain development and adult offspring changes in behavior.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All mice and experimental procedures were conducted using protocols approved by, and in accordance with, the United Kingdom Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and local ethics committee at the University of Southampton under United Kingdom Home Office Project License PPL30/2467 and PPL30/3001. Animals were housed in a specific-pathogen–free facility with 12 h day/night cycles. Before treatment, the animals were housed typically five per cage in conventional caging with aspen sawdust and sizzle nest enriched with plastic tubing and domes. All mice had food and water ad libitum and were fed a maintenance RM1 diet (Special Diet Services, Ltd.) before treatments and where relevant postnatally, with pups weaned at 21 d. Maternal dietary treatments were conducted as previously described (6). Briefly, virgin female MF-1 outbred mice (aged 7 to 8.5 wk) were randomly allocated to one of three isocaloric dietary treatment groups, being fed ad libitum with free access to water: either LPD (9% casein) or NPD (18% casein) (18) throughout gestation only or Emb-LPD exclusively during preimplantation development (from vaginal plug identification until 3.5 d) before being switched to NPD for the remainder of gestation. On the morning of the experiments, dams were killed by cervical dislocation at E12.5, E14.5, or E17.5 in the laboratory, and fetuses were decapitated for brain dissection or processed for subsequent experimentation. For adult offspring analysis, three cohorts of three to four litters were staggered across several months, with a total of three to four litters per group. In each cohort, each group was represented by one or two litters. The same diet regime was followed as in the fetal experiments, followed by RM1 during lactation and to offspring after weaning at 21 d. Litters were normalized to four males and four females at birth. In the morning of the 109th or 110th day after birth, mice were transcardially perfused with 0.9% NaCl containing 5 U/mL heparin sodium (CP Pharmaceuticals) and brains were cut in half sagittally, with one half fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and the other half dissected further into cortex, hippocampus, SVZ, cerebellum, and striatum samples, and then snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. For all experiments, the numbers of mothers and fetuses/offspring per treatment and experimental replicates used are noted in the figure legends.

Behavior, Novel-Object Recognition Assay.

At 41, 64, and 96 d old, each animal was subjected to the novel-object recognition test. Two objects (a can 7 cm high and 3 cm in diameter, and a square sand jar 7 cm high and 3.5 cm wide, heavy enough not to be moved by the mice) were placed at equal distance from the top left corner and the bottom right corner, respectively, of the open arena (no bedding, 28.5 × 28.5 × 25 cm3). The object combinations were changed randomly throughout all trials. All trials were video recorded (camera above the arena). Tests involved two phases—acquisition and retention—with 1 min between them. During the acquisition trial, individual animals were placed into the arena facing the top right corner, with two identical objects, for 4 min, before being removed and placed back into the home cage for 1 min while the arena was cleaned with a 70% ethanol solution. The animals were replaced in the arena for the retention trial, with one of the two familiar objects randomly replaced with a novel item for a further 4 min. Video footage from the retention trial was used for analysis data, in random and blinded order, of exploration behavior (normalized score for smell or nose touch of the object) and duration. Exploration times for the novel object (Tn) and the familiar object (Tf) during the retention trial were used to calculate the discrimination index DI = (Tn − Tf)/(Tn + Tf).

Neurosphere Culture.

On harvesting, all tissues were mechanically dissociated to single-cell suspensions according to established protocols for culture of fetal NSCs (42, 43), and cultured in single-cell suspension at a density of 10 cells per microliter. Growth medium consisted of Neurobasal-A (Invitrogen), supplemented with B27, 2 mM l-glutamine, antibiotic/antimycotic preparation, and growth factors (10 ng/mL human FGFb, 20 ng/mL human EGF, and 2 μg/mL heparin). Sphere counts were performed at day 7 and reflect the number of spheres >100 μm in diameter per well, averaged across at least three wells per sample. Spheres were passaged after 8 d. Passaging was accomplished by centrifugation and 25 cycles of mechanical trituration using a 1-mL pipette, followed by resuspension at 10 cells per microliter in fresh medium.

In Vitro Proliferation Analysis.

Monolayer cultures were used to assess proliferation 3 d after cell plating. Cells in these cultures were plated at equal live cell density on coverslips coated with 0.01% poly-l-ornithine and 50 µg/mL laminin. BrdU labeling was used to allow determination of mitotic and labeling indices by exposing the cultures to 20 µM BrdU over a period of 5 h, followed by fixation and immunostaining. Growth fraction and mitotic index were calculated as the proportion of DAPI-labeled cells stained respectively with Ki67 and BrdU. Labeling index was calculated as the proportion of Ki67-labeled cells stained with BrdU.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Markers.

Cells were incubated in reagents from the fixable Live/Dead Violet Viability stain (Invitrogen) before being treated with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (554714). Cells were then incubated with phycoerythin-congugated anti-Nestin (IC2736P; R&D Systems) and Alexa Fluor 488 anti-Tubulin Beta 3 (BioLegend) or their matching isotype control antibodies. Phenotypic characterization of cells was performed with a nine-color FACSAria cell sorter and FACSDiva Software (version 5.0.3; BD Biosciences).

Immunostaining and Quantification.

Tissue sections (14 μm) were obtained by fixing brains in 4% PFA and sectioning on a cryostat. Cultured cells were fixed in 4% PFA. For BrdU staining, cells were incubated with 2 M hydrochloric acid before staining. Staining was performed on cells and sections using antibodies: mouse anti-Nestin (mab353, 1:100; Millipore), mouse anti-beta-III-tubulin (mms-435p-250, 1:500; Covance), mouse anti-BrdU (B2531, 1:200; Sigma), rabbit anti-Ki67 (VP-RM04, 1:50; Vector Labs), goat anti-Sox2 (SC-17320, 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (9664, 1:400; Cell Signaling Technologies). Secondary antibodies used were donkey Alexa Fluor 488 and 568 (1:200; Invitrogen) raised against appropriate primary sera. For NeuN staining on adult brain sections, postfixation was performed with 4% PFA for 20 min followed by a heat shock citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0) antigen retrieval step. PBS with 0.2% TritonX-100 was used to permeabilize the tissue and 10% donkey serum in PBS for 1 h at 37 °C to block nonspecific epitopes. The primary antibody mouse anti-NeuN (MAB377 clone A60 1:250; Millipore) was added in PBS 10% donkey serum and left to incubate at 4 °C overnight. The sections were permeabilized for 20 min again on the second day, after which the secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse; A21202, 1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added in PBS 10% donkey serum and left to incubate at 37 °C for 2 h. DAPI incubation (CAS 28718-90-3, 1 mg/mL; Calbiochem) was carried out for 5 min before mounting the slides. For each marker, sections were stained and analyzed using ImageJ. The density of staining (pixel intensity within an area) was analyzed for beta-III-tubulin, within at least three randomly selected fields. For Ki67, cleaved caspase-3, Sox2, and NeuN, the number of positive cells was counted per field and compared with DAPI+ cell numbers within at least three randomly selected fields per layer per image and with at least three images per brain.

Cortex Thickness.

Images of the somatosensory cortex were taken from DAPI-stained sections and analyzed using ImageJ. One cortex thickness measurement was taken per image, with three images per brain. Measures were taken in micrometers.

qRT-PCR.

RNA was isolated using a lipid tissue RNA isolation kit and protocol from Qiagen, Inc. Snap-frozen brain cortex regions were homogenized using a handheld electric homogenizer with the QIAzol reagent. RNA was eluted from the midi columns with two aliquots of 250 µL each of RNase-free water. Concentration and RNA integrity was measured by a bioanalyzer (Agilent). RNA samples were stored at −80 °C until use. A 1-µg portion of RNA was transcribed into cDNA using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) as per the manufacturer’s protocol for a 20-µL reaction using a PTC240 Tetrad 2 Peltier Thermal Cycler (MJ Research). cDNA was stored at −20 °C. qPCR was then performed using SYBR green (PrimerDesign) on a C1000 Thermal Cycler with a CFX96 detection module (Bio-Rad). MJ Opticon Monitor Software (Bio-Rad) was used to plot fluorescence intensity over time, and C(t) values were calculated for each marker at the autocalculated threshold. Melting curves in 0.2 °C intervals between 55 °C and 90 °C were compiled to ensure that the template was amplified specifically. C(t) values for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) and Adaptor Related Protein Complex 3 Delta 1 Subunit (Ap3d1) levels were measured for each cDNA sample as reference C(t) values. Reference genes were selected using the 12 geNorm kit (PrimerDesign). C(t) values were obtained and relative gene expression levels were calculated by normalizing the gene C(t) values to the Gapdh and Ap3d1 C(t) values using the 2-ΔΔC(t) method such that relative expression = 2(C(t) Gapdh&Ap3d1 − C(t) gene). Primers for Fxr1, Fmr1, Tdp2, Ap3d1, and Gapdh are proprietary property of PrimerDesign. Primers used for Fxr2 were FXR2_forward: TCAGGACAGAAGGGTGACTC and FXR2_reverse: GAAAGGAGGGATGTGGACCG.

Statistical Analysis.

Unless otherwise stated, data were analyzed using a multilevel linear regression model using PASW for Windows program, version 21 (SPSS), in which there was a random effect assigned to each litter. Thus, we evaluated both between-litter and within-litter effects. We included terms for the litter size and for the sex of the offspring, where appropriate. We used indicator variables to compare the Emb-LPD and the LPD with the NPD. This showed that differences identified between treatment groups are independent of maternal origin of litter and litter size (44). Boxes represent interquartile ranges, with middle lines representing the medians; whiskers (error bars) above and below the box indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Clive Osmond for help with statistical analysis; staff from the University of Southampton Biomedical Research Facility for animal provision and maintenance; and the Flow Cytometry Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton for flow cytometry assistance and maintenance. The studies reported here were supported through awards from the Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton; the Wessex Medical Research and Rosetrees Trust (M327-CD1) (to S.W.-M.); the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/I001840/1, BB/F007450/1); the EU-FP7 EpiHealth programs and the Gerald Kerkut Trust (to T.P.F.); the Leonard Thomas Fund (to L.E.A.); the Dr. Sanderson bursary (to L.E.A. and P.J.S.); and the Wolfson Foundation (C.J.A.). Funders had no role in the conception and design of the study, provision of study material, collection of data, data analysis and interpretation, or manuscript writing.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 7852.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1721876115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Kajantie E, Eriksson JG. Growth and chronic disease: Findings in the Helsinki Birth Cohort. Ann Hum Biol. 2009;36:445–458. doi: 10.1080/03014460902980295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker DJ, Thornburg KL. The obstetric origins of health for a lifetime. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56:511–519. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31829cb9ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raikkonen K, et al. Early life origins cognitive decline: Findings in elderly men in the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wahlbeck K, Forsén T, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Eriksson JG. Association of schizophrenia with low maternal body mass index, small size at birth, and thinness during childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:48–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roseboom TJ, Painter RC, van Abeelen AF, Veenendaal MV, de Rooij SR. Hungry in the womb: What are the consequences? Lessons from the Dutch famine. Maturitas. 2011;70:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watkins AJ, et al. Adaptive responses by mouse early embryos to maternal diet protect fetal growth but predispose to adult onset disease. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:299–306. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.064220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming TP, et al. Do little embryos make big decisions? How maternal dietary protein restriction can permanently change an embryo’s potential, affecting adult health. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2015;27:684–692. doi: 10.1071/RD14455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akitake Y, et al. Moderate maternal food restriction in mice impairs physical growth, behavior, and neurodevelopment of offspring. Nutr Res. 2015;35:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alamy M, Bengelloun WA. Malnutrition and brain development: An analysis of the effects of inadequate diet during different stages of life in rat. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1463–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belluscio LM, Berardino BG, Ferroni NM, Ceruti JM, Cánepa ET. Early protein malnutrition negatively impacts physical growth and neurological reflexes and evokes anxiety and depressive-like behaviors. Physiol Behav. 2014;129:237–254. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kehoe P, Mallinson K, Bronzino J, McCormick CM. Effects of prenatal protein malnutrition and neonatal stress on CNS responsiveness. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;132:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mokler DJ, Torres OI, Galler JR, Morgane PJ. Stress-induced changes in extracellular dopamine and serotonin in the medial prefrontal cortex and dorsal hippocampus of prenatally malnourished rats. Brain Res. 2007;1148:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resnick O, Morgane PJ. Ontogeny of the levels of serotonin in various parts of the brain in severely protein malnourished rats. Brain Res. 1984;303:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amarger V, et al. Protein content and methyl donors in maternal diet interact to influence the proliferation rate and cell fate of neural stem cells in rat hippocampus. Nutrients. 2014;6:4200–4217. doi: 10.3390/nu6104200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckert JJ, et al. Metabolic induction and early responses of mouse blastocyst developmental programming following maternal low protein diet affecting life-long health. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kermack AJ, et al. Amino acid composition of human uterine fluid: Association with age, lifestyle and gynaecological pathology. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:917–924. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun C, et al. Mouse early extra-embryonic lineages activate compensatory endocytosis in response to poor maternal nutrition. Development. 2014;141:1140–1150. doi: 10.1242/dev.103952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watkins AJ, Lucas ES, Wilkins A, Cagampang FR, Fleming TP. Maternal periconceptional and gestational low protein diet affects mouse offspring growth, cardiovascular and adipose phenotype at 1 year of age. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox A, Fleming TP, Smyth N. Embryonic stem cells: Modelling effects of early embryo environment on developmental potential. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2011;2:S93–S94. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denisenko O, et al. Regulation of ribosomal RNA expression across the lifespan is fine-tuned by maternal diet before implantation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1859:906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burdge GC, Dunn RL, Wootton SA, Jackson AA. Effect of reduced dietary protein intake on hepatic and plasma essential fatty acid concentrations in the adult female rat: Effect of pregnancy and consequences for accumulation of arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acids in fetal liver and brain. Br J Nutr. 2002;88:379–387. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torres N, et al. Protein restriction during pregnancy affects maternal liver lipid metabolism and fetal brain lipid composition in the rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E270–E277. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00437.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakayori N, et al. Distinctive effects of arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on neural stem/progenitor cells. Genes Cells. 2011;16:778–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katakura M, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid promotes neuronal differentiation by regulating basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors and cell cycle in neural stem cells. Neuroscience. 2009;160:651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kageyama R, Ohtsuka T, Kobayashi T. Roles of Hes genes in neural development. Dev Growth Differ. 2008;50(Suppl 1):S97–S103. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohtsuka T, Sakamoto M, Guillemot F, Kageyama R. Roles of the basic helix-loop-helix genes Hes1 and Hes5 in expansion of neural stem cells of the developing brain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30467–30474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102420200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rashid MA, Katakura M, Kharebava G, Kevala K, Kim HY. N-Docosahexaenoylethanolamine is a potent neurogenic factor for neural stem cell differentiation. J Neurochem. 2013;125:869–884. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeMar JC, Jr, Ma K, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Half-lives of docosahexaenoic acid in rat brain phospholipids are prolonged by 15 weeks of nutritional deprivation of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1125–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korzhevskii DE, Lentsman MV, Gilyarov AV, Kirik OV, Vlasov TD. Induction of nestin synthesis in rat brain cells by ischemic damage. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2008;38:139–143. doi: 10.1007/s11055-008-0020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park JH, et al. Calorie restriction alleviates the age-related decrease in neural progenitor cell division in the aging brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;37:1987–1993. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plümpe T, et al. Variability of doublecortin-associated dendrite maturation in adult hippocampal neurogenesis is independent of the regulation of precursor cell proliferation. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blaschke AJ, Staley K, Chun J. Widespread programmed cell death in proliferative and postmitotic regions of the fetal cerebral cortex. Development. 1996;122:1165–1174. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.4.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spencer CM, et al. Exaggerated behavioral phenotypes in Fmr1/Fxr2 double knockout mice reveal a functional genetic interaction between Fragile X-related proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1984–1994. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bontekoe CJ, et al. Knockout mouse model for Fxr2: A model for mental retardation. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:487–498. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nolan SO, et al. Deletion of Fmr1 results in sex-specific changes in behavior. Brain Behav. 2017;7:e00800. doi: 10.1002/brb3.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaudissard J, et al. Behavioral abnormalities in the Fmr1-KO2 mouse model of fragile X syndrome: The relevance of early life phases. Autism Res. 2017;10:1584–1596. doi: 10.1002/aur.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoll G, et al. Deletion of TOP3β, a component of FMRP-containing mRNPs, contributes to neurodevelopmental disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1228–1237. doi: 10.1038/nn.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu D, et al. Top3β is an RNA topoisomerase that works with fragile X syndrome protein to promote synapse formation. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1238–1247. doi: 10.1038/nn.3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao R, Huang SY, Marchand C, Pommier Y. Biochemical characterization of human tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 2 (TDP2/TTRAP): A Mg(2+)/Mn(2+)-dependent phosphodiesterase specific for the repair of topoisomerase cleavage complexes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:30842–30852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.393983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pommier Y, et al. Tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterases (TDP1 and TDP2) DNA Repair (Amst) 2014;19:114–129. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gómez-Herreros F, et al. TDP2 protects transcription from abortive topoisomerase activity and is required for normal neural function. Nat Genet. 2014;46:516–521. doi: 10.1038/ng.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science. 1992;255:1707–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morshead CM, et al. Neural stem cells in the adult mammalian forebrain: A relatively quiescent subpopulation of subependymal cells. Neuron. 1994;13:1071–1082. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watkins AJ, et al. Mouse embryo culture induces changes in postnatal phenotype including raised systolic blood pressure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5449–5454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610317104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.