Abstract

In the present paper, we give a selective review of some very recent works concerning the non-stationary regimes emerging in various one- and two-dimensional models incorporating internal rotators. In one-dimensional models, these regimes are characterized by the intense energy transfer from the outer element, subjected to initial or harmonic excitation, to the internal rotator. As for the two-dimensional models (incorporating internal rotators), we will mainly focus on the two special dynamical states, namely a state of the near-complete energy transfer from longitudinal to lateral vibrations of the outer element as well as the state of a permanent, unidirectional energy locking with mild, spatial energy exchanges. In this review, we will discuss the recent theoretical and experimental advancements in the study of essentially nonlinear mechanisms governing the formation and bifurcations of the regimes of intense energy transfer. The present review is composed of two parts. The first part will be mainly devoted to the emergence of resonant energy transfer states in one-dimensional models incorporating internal rotators, while the second part will be mainly concerned with the manifestation of various energy transfer states in two-dimensional ones.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Nonlinear energy transfer in dynamical and acoustical systems’.

Keywords: nonlinear beats, energy localization

1. Introduction

Nonlinear energy transfer remains one of the intensively studied topics of applied physics [1–5] and engineering sciences [5–10]. This phenomenon is ubiquitous in a wide variety of physical and engineering problems such as resonant control of nonlinear waves [11–13], excitation of ion acoustic waves [14], resonant bubble oscillations [15], energy transfer in granular crystals [16–18], passive vibration mitigation in structures [6–8], seismic mitigation [19] and chatter control of turning processes [20], to name a few.

One of the rapidly developing strategies of passive control of vibrations in various engineering structures is based on the well-known nonlinear phenomenon of targeted energy transfer (TET) [6,7]. This regime is characterized by a significant, resonance energy transfer from the directly loaded structure to the essentially nonlinear attachment (nonlinear energy sink—NES) in an irreversible fashion. Here it is worthwhile emphasizing that the transferred energy is locked and gradually damped on the NES, thus significantly reducing the level of unwanted vibrations on the loaded structure. Quite recently a novel type of essentially nonlinear, vibration absorber (NES) was proposed by Gendelman and colleagues [21–23]. This NES is based on an eccentric rotator, inertially coupled to a primary structure with the freedom to oscillate or rotate in a horizontal plane.

Additional types of non-stationary regimes of irreversible (unidirectional) energy transfer can be found in the coupled oscillatory models containing the time-varying parameters [24,25] (e.g. time-varying effective stiffness, time-varying frequency of the external forcing, etc.).

In the present paper, we will focus on the different types of non-stationary regimes manifested by the recurrent, near-complete energy exchanges between the different d.f. of the system (e.g. two coupled oscillators, oscillatory chains [26,27], harmonically forced oscillator coupled to the NES [25]) as well as the regimes of TET. The occurrence of these regimes is stipulated by the existence of special resonant conditions.

Obviously enough, efficient control of transient vibrations emerging in various mechanical structures requires deep theoretical understanding of non-stationary processes which are ubiquitous to the majority of dynamical systems. Obviously enough, these special, non-stationary system states require some new approaches which differ highly from those existing for the analysis of common stationary (steady-state) processes.

Of late, the original concept of limiting phase trajectories (LPTs) was introduced by Manevitch and colleagues [26–28]. In these studies the authors suggested quite a new approach to the regimes of intense nonlinear beats emerging in the various oscillatory models. By the term limiting phase trajectory (LPT) one usually refers to the unique trajectory on the phase plane of the slow-flow model. This unique trajectory corresponds to the regime of resonant, recurrent energy transfer between the two coupled oscillatory subsystems (these can be single oscillators of the two-oscillator model or a group of oscillators of a certain oscillatory chain [27]) recurrently passing through the state of complete energy localization on one of the subsystems (see e.g. [26–28]).

In the present review paper, we review several recent theoretical and experimental studies of highly nonlinear, non-stationary regimes emerging in one-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D), locally resonant structures incorporating internal rotators. We will focus on the theoretical and experimental studies concerned with the non-stationary regimes of intense energy transfer. Special emphasis of the present study will be devoted to the analytical and numerical investigation of the relatively new mechanism emerging in 2D models of spontaneous transition from regimes of one-directional, spatial energy locking (entrapment) to bi-directional, intense energy transfer between axial and lateral vibrations of 2D structures.

2. Resonant energy transfer in one-dimensional models with internal rotators

Passive shock mitigation and vibration absorption in mechanical models remains one of the most extensively studied problems in structural vibrations [7,8,29,30]. One well-known solution (see [29,30]) exploits the linear tuned mass dampers (TMDs) attached to the externally loaded mechanical structures. To this day, the topic of vibration suppression in externally loaded structures attracts great interest of researchers from diverse engineering communities. One of the recent and broadly developing technologies for passive vibration absorption, vibration isolation and shock mitigation is based on the usage of essentially nonlinear elements incorporated in externally loaded mechanical structures. Thus, as can be seen from some very recent theoretical and experimental studies, the small-mass elements attached to the primary system through the essentially nonlinear spring and dashpot can serve as highly efficient, broadband vibration absorbers. These small-mass attachments are usually referred to as NESs and broadly applied for the purposes of vibration absorption in various models. Numerous theoretical and experimental studies have demonstrated that the NES attached to the externally loaded primary system may lead to the formation of quite an intriguing phenomenon which is commonly referred to as TET [7,8]. This phenomenon is manifested by significant energy flow from the externally excited primary system to the attached NES (or system of NESs) in an irreversible fashion. To the best of our knowledge, the first NES of essentially nonlinear type has been proposed in the pioneering theoretical and experimental studies by Gendelman, Vakakis, Manevitch, Bergman, McFarland, Lamarque and collaborators [7,31–39]. All these works have considered the NES incorporating perfectly cubic nonlinearity.

Of late, the concept of NES has been significantly extended to the new type of NESs incorporating essential nonlinearities which differ from the originally proposed cubic nonlinearity (e.g. vibro-impact NES, rotational NES, NES incorporating nonlinearity of general non-polynomial type, NES with multiple states of equilibrium, non-smooth NES).

These NESs of the new type have also become a subject of intense experimental research and have been tested in different applications [21–23,35–49].

In the present section, we will review the recent developments in theoretical and experimental studies of the resonant energy transfer phenomenon emerging in 1D models incorporating the NES of a special type. This type of NES is usually referred to in the literature as an eccentric rotational NES (rotator). The NES of this special type is based on an eccentric rotator, or pendulum, inertially coupled to a primary structure with the freedom to oscillate or rotate in a horizontal plane.

A systematic study of non-stationary response regimes emerging in externally excited 1D models with internal rotators starts with the theoretical and experimental work by Gendelman et al. [21]. The first model under consideration comprised an initially excited linear oscillator with an internal rotator. Analysis presented in the study provided some qualitative analytical predictions of the formation of various response regimes. These regimes have been classified by the motion of the internal rotator, i.e. oscillatory response, intermittent response, rotational response. Transitions between the various types of response regimes have been investigated analytically and numerically and have been confirmed experimentally. Authors have demonstrated the emergence of TET from the initially excited cart to the internal rotator for the first time in this study. The more extensive analytical and numerical study of the regimes of unidirectional, resonant energy transfer exhibited by the same model can be found in [22]. In the same work, the authors have analysed the mechanism of damped transitions and derived the analytical approximation for the damped system response (TET) in the vicinity of 1 : 1 resonance. This analytical approximation was based on the assumption of resonance capture followed by the super-slow, damped system evolution in the vicinity of the 1 : 1 resonance manifold. Using the same analytical approach, the authors successfully described the most significant phase of the TET process, characterized by the fast decay of the response amplitude of a primary mass due to the resonant motion of the internal rotator and derived the theoretical threshold for the escape from 1 : 1 resonance. Another interesting study of the dynamics of this 2 d.f., inertially coupled model has revealed the quite unusual type of nonlinear normal modes (NNMs) incorporating both rotational and oscillatory motion [23]. In the same study, the authors demonstrated the alternating transitions between chaotic and regular motion of the lightly damped structures starting at the high energy level. These transitions have been explained by the transient resonance captures in the vicinity of different resonant oscillatory states (NNMs).

Up to now we have discussed solely the response regimes of the models subjected to impulsive loading. One of the first attempts to describe the response of a similar 2 d.f. system with an internal rotator, subjected to a harmonic base excitation, has been reported in [50]. Analysis of stationary response regimes of the oscillator–pendulum system subjected to a base excitation has been presented in this study. Conditions for the existence and stability of the steady-state response regimes have been formulated in the study.

All these fundamental studies concerned with the stationary and non-stationary response regimes emerging in the inertially coupled 1 d.f. models have paved a way for an extensive analytical, computational and experimental research of resonant energy transport in the more complex 1D [44–47] and 2D mechanical structures with internal rotators. In the rest of the present section we will discuss the more practical aspects of the rotational NES model inspired by the aforementioned fundamental studies.

As we have emphasized above, the unique dynamical properties of NESs are majorly exploited for the purpose of passive vibration suppression in mechanical structures being subjected to any kind of impulsive, transient or harmonic broadband loading. Earlier works in the field of vibration absorption have demonstrated the tremendous capabilities of the NES model (incorporating a pure cubic nonlinearity) to efficiently operate over the broad frequency range. This spectacular property of the purely nonlinear vibration absorber is obviously impossible for conventional, linear, TMDs. Based on some recent works concerned with the dynamical properties of rotational NESs, one may wonder whether its applicability for broadband vibration absorption can be enhanced. The first attempt to answer this question can be found in some relatively recent work by Farid & Gendelman [44].

It is a well-known fact that the usual NES designs possess quite obvious drawbacks when exploited for vibration suppression in mechanical models subjected to impulsive loading as they are efficient only in the limited range of initial excitation energies. The reason for this limitation is quite simple. As we have already pointed out above, the mechanism of TET is completely based on a transient resonance capture. Therefore, if the initial excitation is below a certain threshold, then the energy supplied to the NES is insufficient to satisfy the necessary conditions for resonance capture. However, if the initial energy level is too high, then through resonance capture, the actual energy dissipation process may take too long. Many studies have been devoted to the efficient design of NESs with a broader operation range in terms of the initial excitation energies. For instance, in some earlier works it was demonstrated that by the application of multiple d.f., the NES operation range can be broadened significantly. It is worthwhile noting that all the engineering solutions relying on multiple d.f. NESs are less attractive as they require a more complex design and are harder to control.

The first attempt to broaden the energy range of the NES without increasing its number of d.f. has been reported in [44]. The whole idea is quite original, simple and based on the obvious dynamical properties of a pendulum. Thus for sufficiently low excitation energy, a pendulum exhibits almost linear oscillations (where the free vibration frequency is close to the natural frequency). However, for very high excitation energy the motion of a pendulum turns into pure rotations. Therefore, in the limit of small energy vibrations one can tune the pendulum with respect to its linearized frequency being close to the frequency of the primary system (i.e. tuning of the classical linear TMD). However, in the limit of high-energy vibrations the same pendulum will exhibit properties similar to those of the rotational NES. In the same work, the authors presented a thorough analytical and numerical study of the problem of vibration mitigation in a 2 d.f. oscillator-pendulum model where the primary system (i.e. linear oscillator) is subject to an impulsive loading. In the same study, it was demonstrated that a regular damped pendulum may be efficiently exploited as a NES for the purpose of suppression of impulsive excitations in a broad energy range.

Some recent theoretical and experimental works have studied the effect of rotational NESs on vortex-shedding and vortex-induced vibration of a sprung circular cylinder. Thus in some recent studies reported in [45], the authors computationally investigated the dynamics of a sprung circular cylinder constrained to transverse vortex-induced vibration (VIV) in an incompressible flow internally coupled to a nonlinear rotational dissipative element. The dissipative element is a rotational NES comprising a mass rotating at a fixed radius about the centre of the cylinder and a linear viscous damper. In the problem under consideration, the Reynolds number is assumed to be in the range 20 < Re < 120, while the cylinder is constrained to rectilinear motion transverse to the mean flow. As demonstrated in the study, the rotational NES is capable of a significant suppression of vortex-induced vibration. In addition to the VIV suppression, the rotational NES gives rise to a range of qualitatively new dynamical effects which are not found in transverse VIV of a sprung cylinder free of any internal attachment. In particular, as it was demonstrated by Tumkur et al. [45], the attached rotational component behaves as a regular NES which is able to absorb energy of the rectilinearly vibrating cylinder in an irreversible fashion. As we have already mentioned above, this process of ‘one-way’ energy flow from the externally excited primary structure to the attachment is usually referred to as a TET. In the same study, Tumkur et al. [45] have found out that, in addition to the TET process, the effect of a rotational NES on the response of a vibrating cylinder gives rise to some new phenomena which cannot be found in the transverse VIV of a cylinder with no attachment. One of such phenomena is characterized by the alternation of the phases of regular response and chaotic bursts. During the phase of a regular motion the system exhibits a unidirectional rotation of NES and a significant drop in the amplitude of cylinder vibrations as well as the lift and drag coefficients. This phase of the response is also characterized by a considerable elongation and symmetrization of the attached vorticity. The latter result can be considered as an attempt of use of the internally rotating NES in order to stabilize the system in the steady, symmetric, motionless-cylinder position passively.

Based on the computational results reported in [45], Blanchard et al. [46] derived a reduced-order analytical model corresponding to the fluid–structure interaction problem comprising the transversely vibrating sprung cylinder coupled to a rotational NES. Further analysis has shown that the intermittent system response which is characterized by the alternation between the states of regular response and the temporary chaotic states shown in [45] can be explained by the sequence of resonance captures leading to the unidirectional, resonant energy flow (TET) from the cylinder to the rotator. The response of a consequent resonance capture is manifested by the phases of transient stabilization of rectilinear cylinder motion followed by the escape from resonance, resulting in chaotic bursts. The detailed computational study of the mechanism governing the aforementioned phenomenon of vortex elongation earlier reported in [45] can be found in [47].

Up to now we have described only the simplest configurations of the oscillator rotator/pendulum models subject to various types of external loading such as the initial excitation, harmonic forcing and self-induced excitation. However, as we mentioned in passing earlier, unless some special design of a tuned NES is considered (see [44]), the single d.f. NES can be rather sensitive to the amplitude of external forcing, initial conditions as well as the initial energy excitation level. Unfortunately, a single d.f. NES when applied to the impulsively loaded structures exhibits high TET efficiency only in the relatively narrow ranges of external forcing amplitudes. To overcome these drawbacks of the single d.f. NES, solutions exploiting the multiple d.f. NESs have been proved more efficient for the purpose of broad energy range mitigation. Though there is obvious enhancement of the NES efficacy demonstrated in several theoretical studies, adding an additional mass puts some requirements on the operational space of the multiple d.f. absorbers, which makes the design more complex. Additionally, as we have already pointed out above, the dynamics of such multiple d.f. NES models can become highly chaotic and therefore can be hardly controlled using the well-known essentially nonlinear passive control strategies. Another very original design of the combined multiple d.f. NES has been proposed in [48]. The proposed model comprises the single d.f. primary system, subjected to the impulsive loading and coupled to the original cubic-type NES, which incorporates the internal rotator. This 2 d.f. NES model, on the one hand, can efficiently operate in the broad energy range and, on the other hand, does not require additional space. Analysis of the combined NES model presented in [48] has shown its significantly enhanced performance in terms of the width of the efficient operation energy range compared to the typical single d.f. NESs, which is without the extension of its operational space. Another quite interesting phenomenon reported in the same study [48] was the ‘amplitude locking’ (AL). Thus, for large enough frequencies the amplitude of oscillations of the cubic oscillator becomes independent of the frequency of these oscillations. This phenomenon has been coined AL, as the amplitude of the response remains nearly constant over some very broad range of energies and frequencies.

Another numerical and experimental study [49] has been concerned with the dynamics of a 2 d.f. primary system subject to impulsive loading where the second d.f. is attached to the rotational NES. Assuming a direct shock excitation applied on the first d.f. the authors demonstrated the resonance capture of the transient dynamics into a rotational mode exhibited by the NES. This transient response is characterized by a rapid dissipation of a significant portion of initial input energy supplied to the primary structure. This study has demonstrated that the rotatory NES is capable of passively transferring a significant portion of the shock energy from low- to high-frequency modes of the primary structure, where energy is more effectively dissipated by the inherent dynamics of the structure itself. Thus, importantly enough, apart from the regular mechanism of TET where the significant amount of input energy is passively absorbed and locally dissipated, the NES nonlinearly distributes a portion of the input energy from the lower to the higher modes, resulting in efficient vibration mitigation. Results of numerical study reported in [49] have been confirmed by a series of experimental tests corresponding to the various amplitudes of the impulsive loading.

We close the present subsection by noting that interest in studying the dynamical properties of internal rotational devices incorporated in various mechanical structures goes beyond academic interest. Recently, the use of internal inertial resonators in complex models [51–54] for the purpose of seismic wave mitigation and spatial passive control of wave propagation has become a subject of broad interest in diverse engineering communities.

3. Resonant energy transfer in two-dimensional models with internal rotators

In the previous subsection, we reviewed some recent analytical, numerical and experimental works concerned with the non-stationary response regimes of various 1D mechanical models incorporating the internal rotator. From the practical viewpoint some of the theoretical and experimental studies discussed in the previous section have been driven by one main objective, which was finding some special dynamical properties of the tuned internal rotator, bringing about efficient TET from the impulsively excited primary structure to the rotational NES (or combined NESs). One of the most natural extensions of these studies would be the analysis of the effect of the internal rotational NES on the non-stationary regimes of 2D vibrations of mechanical structures. In particular, we are mostly interested in developing passive nonlinear strategies for the spatial control of 2D resonant energy flow, which is carried out by the motion of the internal rotational NES.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there exist quite a few theoretical and experimental works which have considered the non-stationary response of two-directional vibrating systems incorporating various kinds of internal rotational devices. Here we mentioned in passing some of them. Thus, in some relatively recent theoretical and experimental works by Ikeda et al. [53] the authors have considered the problem of passive control of vibrations of a flexible tower-like structure using a single spherical pendulum vibration absorber (SPVA). The SPVA is attached to the structure, which is modelled as a 2 d.f. system, subjected to horizontal, harmonic excitation. In another study by Najdecka et al. [54], the authors considered a system that comprised two pendulums mounted on the 2D structure where the primary system is subject to the external harmonic loading. However, in the same study the actual 2D response of the primary system has not been considered. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, none of the existing studies concerned with the dynamics of the 2D models incorporating internal rotators have analysed the non-stationary nature of their response where initial input energy can be spatially converted from axial to lateral vibrations of the internally controlled object.

In the present section, we will introduce the results of some recent works by the authors concerned with the analysis of non-stationary response regimes emerging in the undamped 2D models—incorporating internal rotating devices. In particular, we will discuss the emergence and bifurcations of some special, non-stationary regimes manifested by unidirectional energy locking as well as a complete, bidirectional energy transport controlled by internal rotational devices. To date, the dynamics of highly non-stationary processes of energy transport emerging in 2D models still remain a hardly explored topic where conventional, analytical methods are hardly applicable. Needless to say that in many real physical systems formation of non-stationary regimes is of primary importance.

To make further reading more convenient to the reader, we bring the two main definitions of these special dynamical states which are frequently mentioned in the second part of the review corresponding to the 2D model.

Bidirectional, recurrent, energy transfer—regime of the recurrent energy transport (nonlinear beats) from axial to lateral vibrations of the outer element (controlled by the motion of the internal rotator) being initially excited strictly in the axial (or lateral) direction.

Unidirectional, energy locking—regime of permanent, unidirectional energy localization in the outer element being initially excited strictly in the axial (or lateral) direction.

(a). The two-dimensional anharmonic oscillator with rotator: resonant energy pulsations

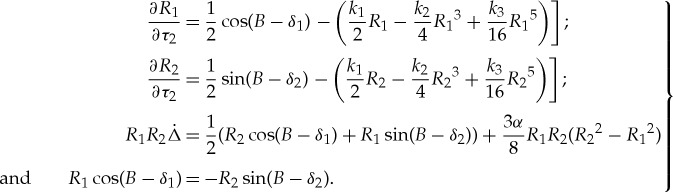

We start our discussion from consideration of the 2D anharmonic oscillator with an internal rotator (figure 1). As it was shown in [55], the system under consideration is described by the following set of non-dimensional equations of motion:

|

3.1 |

where ξ1,2 stand for the axial and lateral deflections of the outer element, respectively, θ is the rotator angle and ϵ is a parameter (i.e. ratio between the mass of the internal rotator and the total system mass) formally declared as a small system parameter  . Assuming 1 : 1 : 1 resonance, we follow the C–A procedure and introduce new variables as follows:

. Assuming 1 : 1 : 1 resonance, we follow the C–A procedure and introduce new variables as follows:

| 3.2 |

where φ1(t), φ2(t) are assumed to be slowly varying in the vicinity of the main resonance. Plugging (3.2) into (3.1) and averaging w.r.t. the dominant resonant frequency, we obtain

|

3.3 |

Following [55], we proceed with the straightforward multiscale expansion with respect to the formal small system parameter ϵ in the form

| 3.4 |

As in [55], the system depicting the evolution of (3.3) on the slow invariant manifold w.r.t. τ2 reads

|

3.5 |

In fact, the second algebraic equation of (3.5) establishes a connection between the horizontal and vertical vibrations of the outer mass through the motion of the internal rotator. Thus in some sense this equation can be viewed as an effective coupling between the axial and the lateral vibrations of the outer unit. It can be easily shown that system (3.5) possesses two integrals of motion. The first integral reads

| 3.6 |

Using (3.6), it is convenient to introduce angular coordinates:

|

3.7 |

Angular representation of (3.7) allows for the reduction to the following planar system:

|

3.8 |

where  . It can be also shown that system (3.8) possesses an additional integral of motion,

. It can be also shown that system (3.8) possesses an additional integral of motion,

| 3.9 |

In fact, system (3.8) depicts the slow evolution on the plane for stable and unstable branches of SIM. Further study of the system dynamics will be fully concentrated on the non-stationary regimes of (3.8) for both cases, i.e. m – even, odd. In figure 2(a,b), we illustrate the series of phase portraits of (3.8) for two distinct values of m, namely m = 0 and m = 1, respectively. As is clear from the phase portraits of figure 2, the regime of full recurrent energy exchange between the axial and lateral vibrations of the outer element exists above a certain critical value of μ = μCR. Thus, for values of μ = σ−1 below a certain critical value (figure 2a(i), 2b(i)) the LPT (depicted by the bold solid line; see the definition above and the corresponding [26–28]) emanating from θ = 0 does not reach θ = π/2. Thus, applying the initial excitation in the axial direction, one observes the permanent, spatial energy locking in the same direction. This regime is referred to in the literature as unidirectional energy locking (see the definition above). As is evident from figure 2a(ii–iv) and 2b(ii–iv), for the case of μ ≥ μCR, LPT passes through the separatrix, which leads to the formation of LPTs of a new type [26–28]. These special trajectories correspond to the regime of complete, recurrent, spatial energy transfer from the axial to lateral vibrations of the outer element (intense nonlinear beats).

Figure 1.

Scheme of the 2D, locally resonant, single-cell model [55]. (Online version in colour.)

Figure 2.

Phase portraits of (3.8) (a) unstable branch: (i) µ = 0.91, (ii) µ = 0.1.21, (iii) µ = 2, (iv) µ = 3.33(b) stable branch: (i) µ = 0.55, (ii) µ = 0.593, (iii) µ = 0.667, (iv) µ = 3.33. Limiting phase trajectories are denoted with the bold solid lines [55].

Bifurcation analysis of LPTs corresponding to the cases of m – even, odd were studied in [55]. In figure 3(a,b), we plot the time histories and Lissajous curves corresponding to the response of the full model under consideration subject to the two distinct initial excitation levels, i.e. above and below the critical threshold . Thus, above the critical value of

. Thus, above the critical value of  (or μ < μCR) (see figure 3a(ii),(iv)), 3(b(ii))) we observe the typical response of a unidirectional energy locking, while below the critical value of

(or μ < μCR) (see figure 3a(ii),(iv)), 3(b(ii))) we observe the typical response of a unidirectional energy locking, while below the critical value of  (or μ ≥ μCR) (see figures 3a(i)(iii)), 3b(i))) we evidence a bidirectional energy channelling response.

(or μ ≥ μCR) (see figures 3a(i)(iii)), 3b(i))) we evidence a bidirectional energy channelling response.

Figure 3.

(a) Time histories of the modulated and localized response of the unit-cell model. (i,iii) Recurrent energy transport between the axial and the lateral vibrations ((i) deflection of the outer element in the axial direction and (iii) deflection of the outer element in the lateral direction). (ii,iv) Permanent energy localization in the axial direction ((ii) deflection of the outer element in the axial direction and (iv) deflection of the outer element in the lateral direction). Thin solid line denotes the true system response (6), while the bold solid line corresponds to the slow-flow model (3.8). System parameters: ε = 0.01, N = 0.5, (i,iii) α = 69.15 (ii,iv) α = 106.67 (b) Lissajous curves corresponding to the (i) recurrent energy transport and (ii) energy localization in the axial direction [55].

(b). The two-dimensional anharmonic oscillator with rotator: low-energy pulsations

We continue our discussion devoted to the nonlinear beating states emerging in (3.1) for the limit of low-energy excitations. Thus, focusing on the 1 : 1 resonant interaction between the axial and the lateral vibrations of the outer element, we introduce complex variables in the following form:

| 3.10 |

To analyse the dynamics of (3.1) in the limit of low-energy excitations, we use the regular, multiscale asymptotic expansion in the form

|

3.11 |

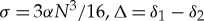

Following the basic steps of the regular multiscale analysis technique [28], one has

|

3.12 |

where ψk0(τ0, τ1) = φk0(τ1)exp (iτ0). It can be shown that system (3.12) possesses the following integral of motion:

| 3.13 |

As in the previous subsection, passing to the angular coordinates representation

| 3.14 |

and performing some trivial algebraic manipulations, one has

|

3.15 |

where Δ = δ1 − δ2. Importantly, system (3.15) possesses the following two integrals:

|

3.16 |

Using the first conserved quantity of (3.16), the slow flow can be reduced to the three-dimensional phase space, yielding

|

3.17 |

To demonstrate the emergence of beating states in the low-energy limit, we analyse the slow-flow model (3.17) for the special case of L = 0, i.e. internal rotator is assumed to be initially at rest. It is easy to see that, in the case of (L = 0), system (3.17) possesses an additional conserved quantity C, given by

| 3.18 |

In figure 4a, we show four different portraits of (3.18) corresponding to the various values of N. From the results of figure 4 one can clearly distinguish between the three distinct types of trajectories: (1) trajectories piercing the same localized state without reaching the opposite one (i.e. Θ = 0, π/2—state of complete energy localization on the axial/lateral vibrations, respectively)); (2) trajectories interconnecting both localized states; (3) trajectories that never pass through any of the states. We define these three types of trajectories as returning, channelling and disconnecting. In figure 4a(i,ii),b(i,ii), one can clearly observe the existence of ‘channelling regions’ containing only the channelling trajectories. These regions gradually shrink with the growing value of N and at a certain critical value of N = NCR = 2−1/2 (figure 4c) vanish [56]. Increasing the value of N further (N > NCR), one can observe the disappearance of the ‘channelling regions’ (figure 4d). In fact, the presence of the ‘channelling regions’ on the projection plane (θ0, Θ) does not necessarily mean that each channelling path connecting the lower state (Θ = 0) with the upper (Θ = π/2) one will lead to the complete energy exchanges. As was shown in [56], the only trajectory of the channelling region corresponding to the complete, recurrent energy transfer must satisfy

| 3.19 |

Figure 4.

(a) Projection of the slow-flow phase space onto the θ0, Θ—plane for the different values of N (3.18): (i) N = 0.25, (ii) N = 0.5, (iii) N = 2−1/2 and (iv) N = 1. Channelling trajectory corresponding to complete bidirectional channelling is denoted with the bold red line; separatrices are denoted with the bold, black solid lines; regular trajectories are denoted with the thin solid lines. (b) Time histories of the response of a reduced slow-flow model (3.17) corresponding to complete recurrent energy channelling [56].

In figure 4b, we plot the time histories of the response of the slow-flow model (3.15) corresponding to the regime of complete recurrent energy channelling. In figure 5a, we plot the response of the full (3.1) and the slow (3.15) models. The time histories corresponding to the predicted regime of complete (N < NCR = 2−1/2) recurrent energy channelling of the slow-flow model (3.15) are compared with those of the full model (1) (figure 5a). The time histories corresponding to the regimes of mild energy transport predicted by the analytical model (i.e. destruction of ‘Channelling Regions’ for N > NCR = 2−1/2) are illustrated in (figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Time histories of the response of a single-cell model (1): (a(i),b(i)) axial deflection, (a(ii),b(ii)) lateral deflection, (a(iii),b(iii)) rotator angle. The blue solid line corresponds to the response of the full model, while the red solid line is related to the response of the reduced slow-flow model (3.15). (a) Complete recurrent energy channelling: system parameters:  . (b) Incomplete recurrent energy: system parameters:

. (b) Incomplete recurrent energy: system parameters:  [56].

[56].

(c). The chain of coupled two-dimensional oscillators with rotators: wave–wave interaction

As a natural extension of the previously discussed beating states emerging in a single-cell unit model, we consider the problem of resonant, 2D wave manipulation emerging in the oscillatory chain composed of the axially coupled elements. Each element of the chain is subject to the local, linear potential along the lateral direction and incorporates the lightweight internal rotator. The scheme of the model under consideration is illustrated in figure 6.

Figure 6.

Scheme of the locally resonant 2D chain [57].

The non-dimensional set of the governing equations of motion reads

|

3.20 |

Here ξn, χn stand for the axial and lateral deflections of the nth outer element, respectively, θn is the angle of the rotator attached to the nth outer element and ϵ is formally declared as a small system parameter  which has exactly the same physical meaning as shown in §3a. The present model under consideration assumes periodic boundary conditions for the longitudinal motion of the outer elements, which are formulated as follows:

which has exactly the same physical meaning as shown in §3a. The present model under consideration assumes periodic boundary conditions for the longitudinal motion of the outer elements, which are formulated as follows:

| 3.21 |

where N stands for the number of cells included in the chain. In the present study, we focus on the mechanisms of resonant transformations of the longitudinal wave into a shear wave emerging in the locally resonant, quasi-1D chain under consideration in the limit of low-energy excitations. As evident from (3.20), ϵ scales the strength of the coupling between the internal rotator and the outer mass. To analyse the dynamics of (3.20) in the limit of low-energy excitations, we use the regular, multiscale asymptotic expansion. In the present section, we do not give all the details of the multiscale procedure. The interested reader can find all the details of the derivation in [57]. The formal multiscale expansion is considered in the following form:

|

3.22 |

Using the multiscale analysis, we seek the solution in the following waveform:

|

3.23 |

The particular solution considered for the axial displacement (ξn0) consists of the superposition of the travelling wave solution and its slowly evolving offset (C(τ1,…)). In fact, an offset of the travelling wave solution can only build up in the axial direction due to the periodic boundary conditions assumed in this direction. As for the lateral response of the outer elements, no offset of the shear wave solution is possible (in the lateral direction), as all the outer elements are attached to the rigid wall (figure 6). Proceeding with the multiscale analysis as in [57], the following is the explicit expression for the first-order term in the expansion of the angular coordinate (θn1(τ0, τ1,…)):

|

3.24 |

In the present problem under consideration, we are mainly interested in depicting the regimes of nonlinear beats manifested by the spatial transformations undergone by longitudinal and shear waves in complete (bidirectional, recurrent energy channelling) and partial fashion (unidirectional energy locking). These wave transformations are in perfect similarity with the beating states governed by the 1 : 1 resonance mechanism discussed in §3b. To this end, we assume the 1 : 1 resonance relation between the axial and the lateral waves. This requirement dictates the following resonance condition imposed on the lateral stiffness component:

| 3.25 |

where the frequency and the wave number of the longitudinal travelling wave are given by  ,

,  . Using the multiscale expansion introduced in [57] yields

. Using the multiscale expansion introduced in [57] yields

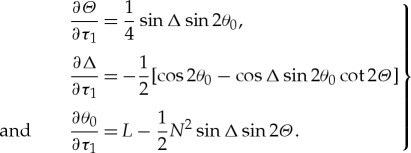

|

3.26 |

In the present subsection, we derive the analytical predictions of the formation of the different regimes of the 2D wave channelling. It can be easily shown that system (3.26) possesses the following conserved quantity:

| 3.27 |

Further, introducing the angular coordinates

| 3.28 |

one obtains the following reduced-order model:

|

3.29 |

The reduced slow-flow model obtained for the wave–wave resonant interaction is exactly similar to the one derived in §3b. Therefore, emergence of similar beating states in the 2D chain under consideration (manifested by the resonant wave transformations) can be predicted using the results of analysis developed in §3b.

To verify the occurrence of the regimes of complete as well as the incomplete bidirectional wave channelling, we performed two independent numerical simulations. To this end we apply an initial excitation on the chain in the form of a longitudinal travelling wave for the two distinct cases, namely  , as well as

, as well as  ,

,  .

.

In figure 7a, we plot again the time histories of the longitudinal (a), transverse (b) response of the 1st, 16th, 31st and 46th outer elements of the chain as well as the response of the 1st, 16th, 31st and 46th internal rotators (c) corresponding to the regime of a complete bidirectional energy transfer predicted for the case of  . Regimes of complete, bidirectional wave channelling predicted by the asymptotical model (3.29) are compared with those of the full system (3.20) (figure 7a). As is clear from the results of figure 7a, the agreement between the analytical and numerical models is fairly good.

. Regimes of complete, bidirectional wave channelling predicted by the asymptotical model (3.29) are compared with those of the full system (3.20) (figure 7a). As is clear from the results of figure 7a, the agreement between the analytical and numerical models is fairly good.

Figure 7.

Time histories of the amplitude response of the longitudinal, transverse travelling waves recorded on the 1st, 16th, 31st and 46th elements as well as the internal field of rotators for both the full (3.20) and the asymptotical (3.29) models ((a) complete and (b) incomplete bidirectional wave channelling) (a(i),b(i)) longitudinal travelling wave, (a(ii),b(ii)) shear travelling wave, (a(iii),b(iii)) collective response of the rotators. The thin solid line corresponds to the response of the full model (3.20) while the bold, red solid line is related to the response of the reduced slow-flow model (3.29). System parameters: N = 60, ε = 0.01, q = 0.3142, κ = ω2 = 0.0979 [57]. I.C. (a)  , (b)

, (b)  , θn(0) = 2π/5 + 0.01cos(qn)sin(2π/5) [57].

, θn(0) = 2π/5 + 0.01cos(qn)sin(2π/5) [57].

The time histories corresponding to the regimes of mild energy transport between the longitudinal and shear travelling waves predicted by the analytical model (i.e. spontaneous annihilation of the ‘channelling regions’ for the case of  ) is illustrated in figure 7b. Results of numerical simulations presented in figure 7 confirm the analytically predicted global bifurcation of the response regime of complete bidirectional wave channelling, leading to unidirectional (longitudinal) wave locking accompanied by mild energy flow between the longitudinal and the shear waves propagating along the outer elements of the chain (figure 7b). To illustrate the bidirectional wave channelling phenomenon, we constructed space–time diagrams (figure 8). In the left and the right panels of figure 8, we plot the density distribution of the kinetic energy (it can be suppressed) along the chain corresponding to longitudinal (figure 8a) and transverse (figure 8b) travelling waves, accordingly.

) is illustrated in figure 7b. Results of numerical simulations presented in figure 7 confirm the analytically predicted global bifurcation of the response regime of complete bidirectional wave channelling, leading to unidirectional (longitudinal) wave locking accompanied by mild energy flow between the longitudinal and the shear waves propagating along the outer elements of the chain (figure 7b). To illustrate the bidirectional wave channelling phenomenon, we constructed space–time diagrams (figure 8). In the left and the right panels of figure 8, we plot the density distribution of the kinetic energy (it can be suppressed) along the chain corresponding to longitudinal (figure 8a) and transverse (figure 8b) travelling waves, accordingly.

Figure 8.

Space–time diagrams (complete bidirectional wave channelling) (a) Kinetic energy distribution corresponding to the longitudinal travelling wave. (b) Kinetic energy distribution corresponding to the transverse travelling wave. System parameters: N = 60, ε = 0.01, q = 0.3142, κ = ω2 = 0.0979. I.C.:  θn(0) = π/3 + 0.005cos(qn)sin(π/3) [57].

θn(0) = π/3 + 0.005cos(qn)sin(π/3) [57].

(d). The two-dimensional anharmonic oscillator with rotator: self-excited oscillations

We close the present discussion with a brief illustration of the intriguing phenomenon of intense nonlinear beats forming in the similar, 2D unit-cell model (comprising an outer mass with an internal rotator) subject to the 2D nonlinear local potential and self-excitation assumed in the axial and lateral directions. The non-dimensional equations of motion read as follows:

|

3.30 |

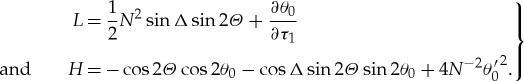

Here all the notations and parameters have been retained exactly as in §3a except the coefficients k1, k2, k3 controlling the strength of the dissipative terms. Following exactly the same steps as in the conservative case (§3a), one derives the following slow-flow model:

|

3.31 |

As in §3a, we introduce the following multiscale expansion:

| 3.32 |

Arguing exactly as in §3a, we derive the reduced model depicting the evolution of the system on the slow-invariant manifold,

|

3.33 |

System (3.33) can be further represented in terms of the real variables  ;

; , and this, in turn, leads us to the following system:

, and this, in turn, leads us to the following system:

|

3.34 |

Using symmetry analysis similar to the one provided in [58], one can obtain an additional invariant of the system for some special choice of the dissipative coefficients. Thus, using (3.34) one has

| 3.35 |

If the relations between the dissipative parameters satisfy the following relations:  , where

, where  is the initial excitation of the system, the value

is the initial excitation of the system, the value  turns into an invariant of the system. Thus using

turns into an invariant of the system. Thus using  , Δ = δ1 − δ2,

, Δ = δ1 − δ2,  N = (|φ10|2 + |φ20|2), one has

N = (|φ10|2 + |φ20|2), one has

|

3.36 |

Here σ = 3αN3/2/4 characterizes conservative nonlinearity, and  , dissipative terms. Considering the reduced system, we illustrate the evolution of the regime of intense energy beats which appears as a limit cycle (red bold line) on the phase planes of figure 9(a(i–iii)). In spite of the fact that the LPT has its special geometrical meaning solely for the two-oscillator, conservative models or externally loaded single d.f. models, we will refer to the limit cycles obtained in the present model as the LPT limit cycles due to their correspondence to the LPT of the conservative subsystem in the limit of zero dissipation.

, dissipative terms. Considering the reduced system, we illustrate the evolution of the regime of intense energy beats which appears as a limit cycle (red bold line) on the phase planes of figure 9(a(i–iii)). In spite of the fact that the LPT has its special geometrical meaning solely for the two-oscillator, conservative models or externally loaded single d.f. models, we will refer to the limit cycles obtained in the present model as the LPT limit cycles due to their correspondence to the LPT of the conservative subsystem in the limit of zero dissipation.

Figure 9.

(a) Phase plane of the SIM with the set of the parameters: m = 1, (i) σ = 2.08, K = 0.52, d = 0.05; (ii) σ = 2.4, K = 0.6, d = 0.6; (iii) σ = 4.5, K = 1.125, d = 0.625; (iv) σ = 2.4, K = 0.6, d = 1.98. (b((i),(ii)) Time histories of the full (blue line) and slow-flow (red line) models corresponding to the beating state emerging in the self-excited model. (a(i)) σ = 5.624, K = 1.2188, d = 0.1 (a(ii)) σ = 5.624, K = 1,3125, d = 0.1 (a(iii)) σ = 5.624, K = 1,359, d = 0.1 (a(iv)) σ = 5.624, K = 1.406, d = 0.1.

The LPT limit cycle emerges for some low values of nonlinear and dissipation parameters of the system. It encircles one of the stationary points (unstable simple periodic regime of the full system (3.30)) at (π/4, 3π/2). In fact, for the lower values of dissipation and nonlinearity (figure 9a(i–iii)), the stable LPT limit cycle corresponds to the intense (nearly complete) energy exchange between the axial and the lateral vibrations of the outer element of the full model (3.30). When the parameters of dissipation d and/or nonlinearity k are gradually increased, the form of the LPT limit cycle on the phase plane is being deformed, while it still remains the only stable attractor of the system. At some point the two pairs of stationary points appear within the LPT limit cycle (figure 9a(ii,iii)). Each pair of stationary points consists of a stable focus and a saddle point. If the parameters k and/or d are further increased, the saddle eventually collides with the stable LPT limiting cycle and the LPT limit cycle vanishes (figure 9(a(iv))). In figure 9(b), we plot the comparison of the beating regime of the full model (3.30) with that of the reduced asymptotic ones (3.34).

4. Conclusion

In the present paper, we introduced some very recent results of the analysis of non-stationary regimes emerging in various 1D and 2D oscillatory structures incorporating internal rotators. As is clear from the present exposition, the response of various 1D and 2D mechanical structures can be efficiently controlled by the motion of the internal rotator. In the 1D models, we have clearly observed situations where the rotating NES incorporated in a certain system configuration or subject to some special initial excitation can become a better solution than the existing NESs in terms of (1) effective initial energy range where the rotating NES is efficient, (2) absorption intensity and (3) effective operation space. In the first part of the review we have seen that the resonance response regimes exhibited by various mechanical structures incorporating these internal devices can be efficiently described analytically. Additionally, the studies of the 1D systems which include the rotating NES devices have shown quite an impressive range of their applicability such as vibration mitigation in impulsively loaded structures, self-excited models as well as the models subject to the harmonic forces. In the 2D model, these small-mass, rotating NES devices have shown the tremendous capability of controlling the 2D energy flow in uni- and multicell models. Results of the analysis presented in the second part of the review are in a full correspondence with the results of the direct numerical analysis. In the 1D case, some analytical and numerical findings have found their confirmation in several experimental works. Overall, the systems reviewed in the present paper have a potential to be applied in various real engineering applications.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

K.V. carried out the analytical and numerical analysis of the dynamical systems presented in 3-1, 3-2, 3-3. M.K. carried out the analytical and numerical analysis of the self-excited vibrations of the 2 d.f. model presented in 3-4 and participated in preparing the manuscript. Y.S. designed and coordinated the study and drafted the manuscript. All the authors gave their final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

M.K. is grateful to Program of Fundamental Researches of the Russian Academy of Sciences (project no. 0082-2014-0013, state registration no. AAAA544 A17-117042510268-5) and Russian Foundation for Basic Research according to the research project no. 18-03-00716. Y.S. is grateful to Israeli Science Foundation, grant no. 1079/16.

References

- 1.Hasselmann K. 1962. On the non-linear energy transfer in a gravity-wave spectrum. I. General Theory. J. Fluid Mech. 12, 481–500. ( 10.1017/S0022112062000373) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kopidakis G, Aubry S, Tsironis GP. 2001. Targeted energy transfer through discrete breathers in nonlinear systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 16550 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.165501) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindberg RR, Charman AE, Wurtele JS, Friedland L. 2004. Robust autoresonant excitation in the plasma beat-wave accelerator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 055001 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.055001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosevich YA, Manevitch LI, Savin AV. 2007. Energy transfer in coupled nonlinear phononic waveguides: transition from wandering breather to nonlinear self-trapping. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 92, 012093 ( 10.1088/1742-6596/92/1/012093) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barak A, Lamhot Y, Friedland L, Segev M. 2009. Autoresonant dynamics of optical guided waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 123901 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.123901) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vakakis AF, Gendelman O, Bergman LA, McFarland DM, Kerschen G, Lee YS. 2008. Nonlinear targeted energy transfer in mechanical and structural systems I. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vakakis AF, Gendelman O, Bergman LA, McFarland DM, Kerschen G, Lee YS. 2009. Nonlinear targeted energy transfer in mechanical and structural systems II. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vakakis AF. 2010. Advanced nonlinear strategies for vibration mitigation and system identification. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manevitch LI, Gendelman O. 2011. Tractable models of solid mechanics, 123, 2040. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kikot I, Manevitch L, Vakakis A. 2015. Non-stationary resonance dynamics of a nonlinear sonic vacuum with grounding supports. J. Sound Vib. 357, 349–364. ( 10.1016/j.jsv.2015.07.026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romeo F, Manevitch LI, Bergman LA, Vakakis AF. 2015. Transient and chaotic low-energy transfers in a system with bistable nonlinearity. Chaos 25, 053109 ( 10.1063/1.4921193) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borich MA, Shagalov AG, Friedland L. 2015. Autoresonant excitation of dark solitons. Phys. Rev. E 91, 012913 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.91.012913) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaakobi O, Friedland L. 2010. Autoresonance of coupled nonlinear waves. AIP Proceedings 1320, 97–103. ( 10.1063/1.3544344) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedland L, Shagalov AG. 2017. Extreme driven ion acoustic waves. Phys. Plasma 24, 082106 ( 10.1063/1.4986031) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng ZC, Leal LG. 1993. On energy transfer in resonant bubble oscillations. Phys. Fluids A Fluid Dyn. 5, 826 ( 10.1063/1.858630) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lydon J, Theocharis G, Daraio C. 2015. Nonlinear resonances and energy transfer in finite granular chains. Phys. Rev. E 91, 023208 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.91.023208) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim E, Chaunsali R, Xu H, Jaworski J, Yang J, Kevrekidis PG, Vakakis AF. 2015. Nonlinear low-to-high-frequency energy cascades in diatomic granular crystals. Phys. Rev. E 92, 062201 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.92.062201) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Moore KJ, Michael McFarland D, Vakakis AF. 2015. Targeted energy transfers and passive acoustic wave redirection in a two-dimensional granular network under periodic excitation. J. Appl. Phys. 118, 234901 ( 10.1063/1.4937898) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nucera F, Vakakis AF, McFarland DM, Bergman LA, Kerschen G. 2007. Targeted energy transfers in vibro-impact oscillators for seismic mitigation. Nonlinear Dyn. 50, 651–677. ( 10.1007/s11071-006-9189-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gourc E, Seguy S, Michon G, Berlioz A. 2013. Chatter control in turning process with a nonlinear energy sink. Adv. Mater. Res. 698, 89–98. ( 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.698.89) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gendelman OV, Sigalov G, Manevitch LI, Mane M, Vakakis AF, Bergman LA. 2012. Dynamics of an eccentric rotational nonlinear energy sink. J. Appl. Mech. 79, 011012 ( 10.1115/1.4005402) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sigalov G, Gendelman OV, AL-Shudeifat MA, Manevitch LI, Vakakis AF, Bergman LA. 2012. Resonance captures and targeted energy transfers in an inertially-coupled rotational nonlinear energy sink. Nonlinear Dyn. 69, 1693–1704. ( 10.1007/s11071-012-0379-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sigalov G, Gendelman OV, AL-Shudeifat MA, Manevitch LI, Vakakis AF, Bergman LA. 2012. Alternation of regular and chaotic dynamics in a simple two-degree-of-freedom system with nonlinear inertial coupling. Chaos 22, 013118 ( 10.1063/1.3683480) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manevitch LI, Kosevich YA, Mane M, Sigalov G, Bergman LA, Vakakis AF. 2008. Towards a new type of energy trap: classical analog of quantum Landau-Zener tunneling. J. Sound Vib. 315, 732–745. ( 10.1016/j.jsv.2007.12.024) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedland L. 2008. Efficient capture of nonlinear oscillations into resonance. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 41, 415101 ( 10.1088/1751-8113/41/41/415101) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manevitch LI. 2007. A new approach to beating phenomena in coupled nonlinear oscillatory chains. Arch. Appl. Mech. 77, 301–312. ( 10.1007/s00419-006-0081-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manevitch LI, Smirnov VV. 2010. Limiting phase trajectories and the origin of energy localization in nonlinear oscillatory chains. Phys. Rev. E 82, 036602 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.036602) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manevitch LI, Kovaleva AS, Shepelev DS. 2011. Non-smooth approximations of the limiting phase trajectories for the Duffing oscillator near 1:1 resonance. Physica D 210, 1–12. ( 10.1016/j.physd.2010.08.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frahm H. 1909. Device for damping vibrations of bodies. US Patent US 989958 A.

- 30.Den Hartog JP. 1956. Mechanical vibration. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gendelman OV. 2001. Transition of energy to a nonlinear localized mode in a highly asymmetric system of two oscillators. Nonlinear Dyn. 25, 237–253. ( 10.1023/A:1012967003477) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gendelman OV, Gorlov DV, Manevitch LI, Musienko AI. 2005. Dynamics of coupled linear and essentially nonlinear oscillators with substantially di_erent masses. J. Sound Vib. 286, 1–19. ( 10.1016/j.jsv.2004.09.021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vakakis AF. 2001. Inducing passive nonlinear energy sinks in vibrating systems. J. Vib. Acoust. 123, 324–332. ( 10.1115/1.1368883) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McFarland DM, Bergman LA, Vakakis AF. 2005. Experimental study of non-linear energy pumping occurring at a single fast frequency. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 40, 891–899. ( 10.1016/j.ijnonlinmec.2004.11.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gourdon E, Alexander N, Taylor C, Lamarque CH, Pernot S. 2007. Nonlinear energy pumping under transient forcing with strongly nonlinear coupling: theoretical and experimental results. J. Sound Vib. 300, 522–551. ( 10.1016/j.jsv.2006.06.074) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Shudeifat MA, Wierschem N, Quinn DD, Vakakis AF, Bergman LA. 2013. Numerical and experimental investigation of a highly effective single-sided vibro-impact nonlinear energy sink for shock mitigation. Int. J. Nonlinear Mech. 52, 96–109. ( 10.1016/j.ijnonlinmec.2013.02.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wierschem NE, et al. 2014. Experimental testing and numerical simulation of a six-story structure incorporating a two-degree-of-freedom nonlinear energy sink. ASCE J. Struct. Eng. 140, 04014027 ( 10.1061/(ASCE)ST.1943-541X.0000978) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo J, Wierschem NE, Hubbard SA, Fahnestock LA, Quinn DD, Mc-Farland DM, Spencer BF Jr, Vakakis AF, Bergman LA. 2014. Large-scale experimental evaluation of a system of nonlinear energy sinks for seismic mitigation. Eng. Struct. 77, 34–48. ( 10.1016/j.engstruct.2014.07.020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gendelman V. 2012. Analytic treatment of a system with a vibro-impact nonlinear energy sink. J. Sound Vib. 331, 4599–4608. ( 10.1016/j.jsv.2012.05.021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Starosvetsky Y, Gendelman OV. 2008. Strongly modulated response in forced 2DOF oscillatory system with essential mass and potential asymmetry. Physica D 237, 1719–1733. ( 10.1016/j.physd.2008.01.019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li T, Seguy S, Berlioz A. 2016. Dynamics of cubic and vibro-impact nonlinear energy sink: Analytical, numerical, and experimental analysis. J. Vib. Acoust. 138, 031010 ( 10.1115/1.4032725) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee YS, Nucera F, Vakakis AF, McFarland DM, Bergman LA. 2009. Periodic orbits, damped transitions and targeted energy transfers in oscillators with vibro-impact attachments. Physica D 238, 1868–1896. ( 10.1016/j.physd.2009.06.013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vakakis AF, Manevitch LI, Mikhlin YV, Pilipchuk VN, Zevin AA. 1996. Normal modes and localization in nonlinear systems. New York: NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farid M, Gendelman OV. 2017. Tuned pendulum as nonlinear energy sink for broad energy range. J. Vib. Control 23, 373–388. ( 10.1177/1077546315578561) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tumkur RKR, Pearlstein AJ, Masud A, Gendelman OV, Blanchard AB, Bergman LA, Vakakis AF. 2017. Effect of an internal nonlinear rotational dissipative element on vortex shedding and vortex-induced vibration of a sprung circular cylinder. J. Fluid Mech. 828, 196–235. ( 10.1017/jfm.2017.504) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blanchard AB, Gendelman OV, Bergman LA, Vakakis AF. 2016. Capture into slow invariant-manifold in the fluid-structure dynamics of a sprung cylinder with a nonlinear rotator. J. Fluids Struct. 63, 155–173. ( 10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2016.03.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blanchard A, Bergman LA, Vakakis AF. 2017. Targeted energy transfer in laminar vortex-induced vibration of a sprung cylinder with a nonlinear dissipative rotator. Physica D 350, 26–44. ( 10.1016/j.physd.2017.03.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benarous N, Gendelman OV. 2016. Nonlinear energy sink with combined nonlinearities: enhanced mitigation of vibrations and amplitude locking phenomenon. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C: J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 230, 21–33. ( 10.1177/0954406215579930) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Shudeifat MA, Wierschem NE, Bergman LA, Vakakis AF. 2017. Numerical and experimental investigations of a rotating nonlinear energy sink. Meccanica 52, 763–779. ( 10.1007/s11012-016-0422-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manevich AI. 2017. Oscillator with a pendulum-rotator: stationary synchronous regimes, stability, vibration mitigation. Procedia Eng. 199, 3462–3467. ( 10.1016/j.proeng.2017.09.452) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finocchio G, Casablanca O, Ricciardi G, Alibrandi U, Garesci F, Chiappini M, Azzerboni B. 2014. Seismic metamaterials based on isochronous mechanical oscillators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 191903 ( 10.1063/1.4876961) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Achaouia Y, Ungureanuab B, Enocha S, Brûle S, Guenneau S. 2016. Seismic waves damping with arrays of inertial resonators. Extreme Mech. Lett. 8, 30–37. ( 10.1016/j.eml.2016.02.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ikeda T, Harata Y, Takeeda A. 2017. Nonlinear responses of spherical pendulum vibration absorbers in tower-like 2DOF structures. Nonlinear Dyn. 88, 2915–2932. ( 10.1007/s11071-017-3421-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Najdecka A, Kapitaniak T, Wiercigroch M. 2015. Synchronous rotational motion of parametric pendulums. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 70, 84–94. ( 10.1016/j.ijnonlinmec.2014.10.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vorotnikov K, Starosvetsky Y. 2015. Nonlinear energy channeling in the two-dimensional, locally resonant, unit-cell model. I. High energy pulsations and routes to energy localization. Chaos 25, 073106 ( 10.1063/1.4922964) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vorotnikov K, Starosvetsky Y. 2015. Nonlinear energy channeling in the two-dimensional, locally resonant, unit-cell model. II. Low energy excitations and uni-directional energy transport. Chaos 25, 073107 ( 10.1063/1.4922965) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vorotnikov K, Starosvetsky Y. 2018. Nonlinear mechanisms of two-dimensional wave-wave transformations in the inertially coupled acoustic structure. J. Appl. Phys. 123, 024904 ( 10.1063/1.4986282) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manevitch LI, Kovaleva MA, Pilipchuk VN. 2013. Non-conventional synchronization of weakly coupled active oscillators. Europhys. Lett. 101, 50002 ( 10.1209/0295-5075/101/50002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.