Abstract

Endocrine disrupting chemical (EDC) exposures during critical periods of gestation cause long-lasting behavioral effects, presumably by disturbing hormonal organization of the brain. Among such EDCs are polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), a class of industrial chemicals. PCB exposure in utero leads to alterations in mating behaviors and other sexually-dimorphic social interactions in rats. Many of the previous studies on social behavior give the experimental animal a single or binary choice. This study applied a more complex behavioral apparatus, an X-shaped Plexiglas apparatus (FourPlex) that enabled an experimental animal exposed to PCBs or vehicle to distinguish and choose among four stimulus animals of the same or opposite sex, and of different hormonal status. We found that rats were able to differentiate among the stimuli in the FourPlex and showed the expected preference for an opposite-sex, hormone-treated rat, particularly for behaviors conducted in close proximity. Prenatal treatment caused subtle shifts in behavior towards stimulus rats in the FourPlex; more robust effects were seen for the sexual dimorphisms in behavior. Importantly, the results differ from our prior results of a simple binary choice model, showing that how an animal behaves in a more complex social paradigm does not predict the outcome in a simple choice model, and vice versa.

Keywords: Endocrine-disrupting Chemicals, Polychlorinated biphenyls, Social Behavior, Sexual Dimorphism

Introduction

Sociality is a complex trait; it arises from the qualities within an individual and the social interactions between individuals. The spectrum of social systems is enormous, from animals that live in total isolation except to mate, and others that live in groups from dyads to thousands. To reduce this complexity in the laboratory setting, behavioral neuroscientists have most commonly taken the reductionist approach. For laboratory rodents, most tests comprise a two-choice paradigm, in which an animal is given a choice between an empty compartment and a stimulus animal, or between two animals that differ in some way (e.g., male vs. female; hormone-primed vs. unprimed; females in different stages of receptivity; etc.). Exceptions have been the socioecological work pioneered by RD Lisk and M McClintock in their laboratory studies of hamsters and rats in large enclosures (Huck, Lisk, & Gore, 1985; McClintock, 1987). More recently, D Kimchi and J Curley independently developed methods of quantifying social interactions within groups of mice (So, Franks, Lim, & Curley, 2015; Weissbrod et al., 2013). Other labs have adopted a multiple-choice system in social models of mate choice (Ferreira-Nuño, Morales-Otal, Paredes, & Velázquez-Moctezuma, 2005). Results of these studies challenge the premise that results from a two-choice paradigm can be extrapolated to more complex interactions; yet the two-choice paradigm continues to be the norm.

Using behavior as a biomarker, our overall goal was to characterize the effects of prenatal exposure to ecologically-relevant levels of a class of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).Humans and wildlife continue to have detectable levels of PCBs in body tissues, despite the ban of these chemicals in developed countries in the 1970s (Gladen, Doucet, & Hansen, 2003). PCBs are persistent, are in the food chain, and can be transported around the world by air and water currents, as well as by migratory species that feed in contaminated areas for part of the year (Crews & Gore, 2011). Previous experimental work from our lab and others on rodents has shown that the brain is sensitive to environmental contamination, especially when exposure occurs during critical periods of development. One such life stage is that of brain organization, when gonadal steroid hormones exert influences on the developing nervous system in a sex-typical manner, setting the stage for subsequent pubertal hormones to activate these neural pathways. This enables the manifestation of sexually dimorphic behaviors involved in reproduction (McCarthy & Arnold, 2011).

Exposures to PCBs during periods of organization and/or activation perturb adult reproductive physiology and behavior (Dickerson, Cunningham, & Gore, 2011; Steinberg, Walker, Juenger, Woller, & Gore, 2008; Walker, Goetz, & Gore, 2013). While other sexually-dimorphic social behaviors have also been investigated for effects of developmental EDC exposures, this research has exclusively relied upon two-choice systems (Belloni et al., 2011; Crews et al., 2012; Gillette et al., 2014; Reilly et al., 2015; Venerosi, Ricceri, Tait, & Calamandrei, 2012; Wolstenholme et al., 2011). However, mate and social choice in naturalistic settings are complex processes that involve, among other things, the complementarity of the chooser and the chosen, with the mutual evaluation of qualities related to a mate's fitness (Crews, 2010; Carson, 2003). In the mate choice literature, the terms appetitive and consummatory are used to describe exploratory/proceptive behaviors prior to mating, and the act of coitus itself, respectively. These concepts that can be extrapolated to more complex social settings where conspecifics are first evaluated (i.e., prosocial behaviors) and subsequently decide to engage in or avoid interactions. Here, we sought to develop and validate a unique four-choice paradigm, referred to as the FourPlex, that retains the basic choice aspect but allows for a greater variety of social stimuli to better model the types of interactions encountered in nature. The stimulus rats were opposite- and same-sex conspecifics of differing hormonal status, and results showed that when this complexity was added, these clear choices of individuals were quite different from those observed in the dyadic situation.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Husbandry

Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN), and all animal procedures were conducted in compliance with a protocol (AUP-2013-00054) approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas at Austin, following the guidelines from the NIH. All animals were housed in a colony room with controlled temperature (22 C) and light cycle (12:12 dark: light, lights on at 2400). Rats were fed a low-phytoestrogen diet (Harlan, Indianapolis, INCat. # 2019) available ad libitum. Virgin females were mated with sexually experienced males. The day following successful mating, as indicated by a sperm-positive vaginal smear, was termed embryonic day 1 (E1).

Gestational Exposure Paradigm

Following confirmed pregnancy, dams were exposed to one of four treatments, administered via intraperitoneal injections, on E16 and E18, the beginning of the period of brain sexual differentiation (Davis, Popper, & Gorski, 1996; Jacobson, Shryne, Shapiro, & Gorski, 1980). The experimental treatment groups were as follows: (1) Vehicle [Negative control - 3% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) in sesame oil] (2) Estradiol benzoate [(EB) 50 μg/kg – positive control for the estrogenic effects of PCBs)] (3) the PCB mixture, Aroclor 1221 (A1221, 0.5 mg/kg), or (4) A1221 (1 mg/kg). We hence forward refer to these groups as vehicle, EB, A1221 (0.5) and A1221 (1.0), respectively, as summarized in Table 1. Selected treatments and dosages were based on prior work conducted in the Gore lab that showed physiological, behavioral, and neuroendocrine effects that were manifested in a sex- and developmental age-specific manner; however, these dosages caused no overt toxicity or pregnancy complications (Dickerson et al., 2011; Steinberg, Juenger, & Gore, 2007; Steinberg et al., 2008; Topper, Walker, & Gore, 2015; Walker et al., 2013, Gillette et al., 2014; Reilly et al. 2015). The number of litters per treatment was 9, 10, 10, and 10, respectively. Although we did not measure body burden or tissue content in the exposed offspring, the literature suggests that maternal-fetal transfer results in a body burden of approximately 1-2 μg/kg A1221, and 100 ng/kg EB in the fetuses (Takagi, Aburada, Hashimoto, & Kitaura, 1986). This falls in the approximate range of human exposures (DeKoning & Karmaus, 2000; Lin, Pessah, & Puschner, 2013).

Table 1. Treatment group terminology.

| Compound | Group name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) 3% in sesame oil | Vehicle | Negative control |

| Estradiol benzoate (EB) 50 μg/kg, dissolved in vehicle | EB | Positive estrogenic control |

| Aroclor 1221 (A1221) 0.5 mg/kg, dissolved in vehicle | A1221 (0.5) | Experimental PCB, lower dosage |

| Aroclor 1221 (A1221) 1.0 mg/kg, dissolved in vehicle | A1221 (1.0) | Experimental PCB, higher dosage |

Pregnant rats were injected subcutaneously in late gestations (embryonic days 16 and 18) with the above treatments. Prenatally exposed rats were the experimental subjects, tested in the FourPlex. Experimental groups are referred to by the group names.

The day of parturition was postnatal day 0 (P0). The day after birth, P1, the pups were weighed and their anogenital distance measured; litters were culled to 4 males and 4 females. The pups were monitored daily for age at eye opening, and body weight and anogenital distance was measured and recorded weekly from birth to weaning, which occurred at P21. Once rehoused in same-sex groups, rats were monitored daily for signs of pubertal development: vaginal opening in females and preputial separation in males (Steinberg et al., 2007; Walker, Kirson, Perez, & Gore, 2012). In females, beginning on the day of vaginal opening, daily vaginal smears were taken and cell cytology was examined as a measure of estrous cyclicity in the females. Weekly body weights continued to be recorded for all animals throughout their lifetimes. There were no effects of prenatal treatment on litter size or sex ratio, age at puberty, or estrous cyclicity (data not shown), as previously published (Gillette et al., 2017; Reilly et al., 2015).

Stimulus Rats

Tenmale and 10 female stimulus rats (Sprague-Dawley) were purchased as young adults from Harlan and gonadectomized under isoflurane anesthesia. After ovariectomy (OVX), females were implanted subcutaneously, in the nape of the neck, with a Silastic capsule (1.98mm I.D. × 3.18mm O.D. × 5-mm length; Dow Corning Corporation, Midland, MI). Five females received capsules packed with 5% crystalline 17β-estradiol (Cat. #: E8875; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with 95% cholesterol; and 5 females received a 100% cholesterol capsule (Wu et al., 2010). Five males received capsules containing100% testosterone (Cat. #: T1500; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 5 received cholesterol capsules (Wu et al., 2010). This resulted in 4 categories of stimulus rats (n = 5 per category) as described below. Stimulus animals were untreated with EDCs or their controls.

BehavioralTesting Paradigm

Behavioral Testing

Beginning when experimental (EDC or vehicle-treated) rats were aged P56, one male and one female from each litter was used for testing. The total number of behaviorally characterized animals was 39 females and 39 males. Females were only used on diestrus to remove the possible confound of estrous cycle status on behavioral outcomes. Testing was conducted under dim red light during the dark period of their light-dark cycle, beginning approximately two hours following lights out. Between animals, the behavioral apparatus was thoroughly cleaned with a 70% ethanol solution.

Apparatus

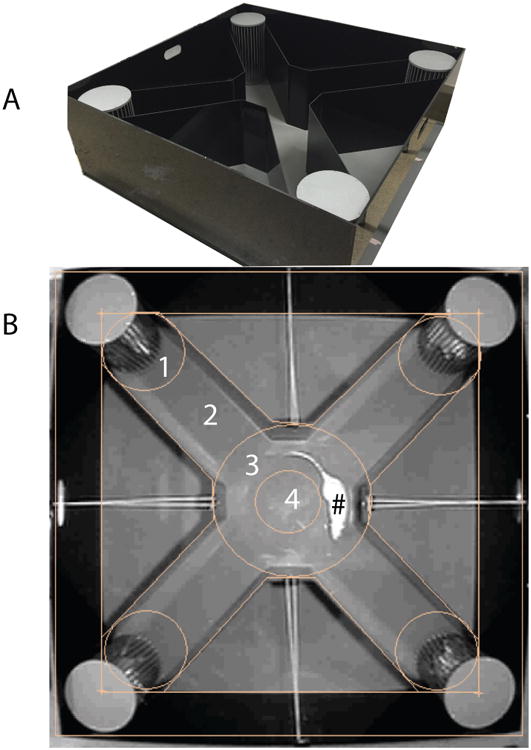

The FourPlex apparatus was designed to reveal the ability of the experimental animal to discriminate between, and preferentially associate with, four possible stimulus partners (Figure 1). Four opaque Plexiglas inserts were constructed and placed inside of a 100 cm × 100cm apparatus (Stoelting), resulting in an X-shaped testing arena. Each of the four arms held a stimulus cage in the far corner of the apparatus. For the purposes of analyses, each arm was further divided into two distinct regions: a zone one body length from the stimulus cage and the residual length of the arm, more remote from the cage.

Figure 1.

The FourPlex apparatus is shown viewed from one corner (A) and in a bird's eye view (B). Four opaque Plexiglas inserts were fabricated to fit inside of a square apparatus (100 cm × 100cm), resulting in an X-shaped testing arena. As seen in B, each of the four arms emanated from a common central area (outer circle labeled “3”) that projected via four arms to a holding cage in each corner. For the purposes of behavioral analyses, each arm was further divided into two distinct regions: a zone one body length from the walls of the stimulus cage (1; the “near” region), and the remaining length of the arm (2; the “remote” region). At the onset of the test, the experimental rat (indicated by #) was placed into the innermost center circle, labeled “4.”

Each test utilized one stimulus rat from each of four categories: a castrated, testosterone-treated male; a castrated male without hormone treatment; an ovariectomized, estradiol-treated female; and an ovariectomized female without hormone treatment. We refer to the stimulus rats relative to the experimental animal as opposite-sex (OS) or same-sex (SS); with (+) or without (-) hormone. Thus, the four stimulus options were: OS+, OS-, SS+, SS-. On the day of testing, stimulus rats were placed, in random order, into one of the four holding cages in the corners. Then, the experimental animal was placed in the middle of the apparatus, marking the beginning of the 10-minutetrial. Between tests, in addition to rearranging the stimulus animals' placement, we periodically replaced stimulus rats to minimize possible consequences of stimulus rat fatigue due to prolonged housing in the holding cages.

BehavioralAnalysis

Animal tracking and behavior scoring

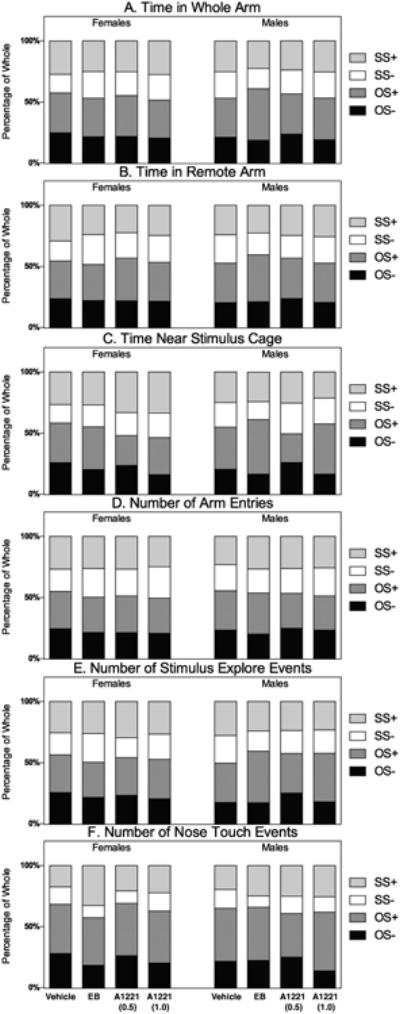

ANY-maze (Stoelting Co.) was used to simultaneously video record and track behaviors during the test. All scoring was done blind to the stimulus or experimental rats' status, and codes were broken only after scoring was complete. We used the software to analyze measures of duration or frequency relative to the animal's position within the apparatus, namely: the time spent in each whole arm (“Time in Whole Arm”); time spent in proximity to the stimulus rats' cage (“Time Near Stimulus Cage” = within one body length); and “Time in Remote Arm,” calculated by subtracting the Time Near Stimulus Cage from the Time in Whole Arm. The number of times each animal entered (80% of body volume) an arm was automatically determined by the software. Then, the video recordings of the tests were manually scored for the following additional behaviors: “Number of Stimulus Explore Events” was the number of times an animal spent investigating the stimulus chamber by sniffing and exploring. The number of times the animals engaged in nose-to-nose contact, or “Number of Nose Touch Events,” was also scored. These investigator-scored behaviors, chosen as the most salient aspect of social investigation, have been used before in a previous study on sociality (Reilly et al., 2015). The relative contribution each stimulus had on the cumulative expression of each behavior can be assessed qualitatively by graphing the means of each measure as a percentage of the whole (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The contribution each stimulus choice had on the behavioral output is shown for the six variables measured. Data are shown separately for each of the four treatment groups in females and males. Bars are always set at 100%, and the percentage of time each behavior is displayed toward each of the stimulus categories is shown. This enables visualization that most behaviors are predominantly exhibited towards the opposite-sex hormone-treated rat, which is the most socially salient, and validates that the FourPlex enables animals to make this distinction. Terminology here and throughout the manuscript is OS-: opposite-sex castrated rat (no hormone); OS+: opposite-sex castrated rat given hormone (estradiol in females, testosterone in males); SS-: same-sex castrated rat, no hormone; and SS+: same-sex castrated rat, given hormone.

During initial analysis, we established that the vast majority of the experimental animals had visited every stimulus option by the end of the first two minutes. When this happened, rats were able to make an ‘Informed Choice’ about all of their stimulus options. An example of a rat visiting each of the four stimulus animals is shown in the Supplemental video. Therefore, our assessment and presentation of social behavior in this study comprises the behavior of the animals during the latter eight-minute period of time during which the experimental animals' behavior reflects this informed choice. Any animals that did not visit all four stimulus options during the two-minute habituation period were removed from all subsequent analyses. This resulted in two rats being excluded: one vehicle female, and one vehicle male.

Statistical Analysis

Outliers

A generalized extreme studentized deviate (ESD) test was used to detect outliers, limited to a maximum of two per group per endpoint. Any individuals repeatedly detected as outliers across multiple endpoints were removed from analyses; this was the case for two vehicle animals (one per sex) and one EB female. Initial statistical analyses were used to identify any potential cohort or litter effects within groups; none were found.

Statistical tests

Because of the sexual dimorphism in social and sociosexual behavior, analyses were done separately for each sex. First, each dataset was inspected for homogeneity of variance and normality to determine if it met criteria for parametric analysis by ANOVA. Those endpoints that met criteria were analyzed this way using R (version 3.3.2), and effect sizes were calculated using the lsr package, and reported as partial eta-squared (ηp2) values in the tables. When data did not satisfy the assumptions for parametric statistics, the non-parametric Kruskal-Walis (KW) test was run using JMP (version 12), with effect sizes reported as epsilon-squared (ε2) values. The Tukey HSD and Steel-Dwass all-pairs tests were used as post-hoc tests for the ANOVA and KW, respectively. In order to determine whether there were sex differences within treatment groups, a Student's t-test was used, and effect sizes were determined using Cohen's d values with the online effect size calculator (http://www.uccs.edu/∼lbecker/). In the tables, those effects that were significant at p < 0.05 and/or had LARGE effect sizes are indicated with bold text.

Multivariate analyses

Principle Components Analysis (PCA) was employed to analyze the entire behavioral ethogram within each sex (Scarpino, Gillette, & Crews, 2014; Gillette et al., 2014). The full list of behaviors in the ethogram is shown in Supplemental Figure S1. Rotation was applied such that the axis would capture the maximal amount of variance. Three principle components were identified as contributing to the majority of the variance (53%) in both sexes (Figure S1). Then, linear discriminate analysis (LDA) was used to conduct systematic pairwise comparisons of each component for all animals, as well as within each sex, to establish how the principle components clustered (Supplemental Table S1). Finally, functional landscape analysis was conducted for sex differences on two behavioral outcomes, one representing an appetitive behavior, the other a consummatory behavior. This allows visual graphic representation and quantitative analysis of phenotypic traits first as absolute measures towards the four stimuli, as well as sex differences for each treatment group (Scarpino, Gillette, & Crews, 2014).

Results

Overview of Behaviors in the FourPlex Test

For each sex, data were initially analyzed for effects of treatment on total time and numbers of events during the 8-minute “informed choice” part of the test, irrespective of which stimulus rat to which they were directed (Table 2). There were no significant effects of treatment in females or males. We also determined sex differences. The number of nose touch events in the EB and A1221 (0.5) groups was significantly sexually dimorphic (male > female) and had LARGE Cohen's d effect sizes. The time near the stimulus cage had a LARGE effect size for the sex difference in vehicle rats (female > male) although it was not statistically significantly different.

Table 2. Summary of Behaviors.

| A Female Treatment Effects | B Male Treatment Effects | C. Sex Effects within Treatment | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Measure | Treatment | Mean (s) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

Mean (s) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

P-Value | Cohen's d | Effect Size | Directionality | ||

| Time in Whole Arm (sec) | Vehicle | 286 | ± | 23 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 3.01 | 0.39 | 0.08 | 289 | ± | 26 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 7.50 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.94 | -0.04 | SMALL | |

| EB | 297 | ± | 14 | 299 | ± | 14 | 0.89 | -0.06 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 330 | ± | 10 | 349 | ± | 16 | 0.34 | -0.44 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 301 | ± | 19 | 300 | ± | 23 | 0.95 | 0.03 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Time in Remote Arm (sec) | Vehicle | 160 | ± | 21 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 5.92 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 200 | ± | 19 | Kruskal-Wallis | X 2(3) = 0.68 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.30 | -0.52 | MEDIUM | |

| EB | 198 | ± | 13 | 202 | ± | 23 | 0.91 | 0.05 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 225 | ± | 13 | 241 | ± | 23 | 0.48 | 0.32 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 188 | ± | 14 | 192 | ± | 20 | 0.62 | -0.23 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Time Near Stimulus Cage (sec) | Vehicle | 126 | ± | 18 | ANOVA | F(3,34)=0.59 | 0.63 | 0.05 | 89 | ± | 12 | ANOVA | F(3,34)=0.62 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.85 | LARGE | F > M |

| EB | 99 | ± | 16 | 97 | ± | 13 | 0.94 | 0.04 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 105 | ± | 14 | 108 | ± | 14 | 0.89 | -0.06 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 114 | ± | 11 | 108 | ± | 6 | 0.66 | 0.20 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Number of Arm Entries | Vehicle | 96 | ± | 6 | ANOVA | F(3,34) = 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.06 | 85 | ± | 9 | Kruskal-Wallis | X 2(3)=7.37 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.48 | SMALL | |

| EB | 95 | ± | 6 | 83 | ± | 4 | 0.12 | 0.74 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 102 | ± | 4 | 92 | ± | 8 | 0.26 | 0.52 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 104 | ± | 7 | 102 | ± | 5 | 0.75 | 0.15 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Number of Stimulus Explore Events | Vehicle | 137 | ± | 26 | ANOVA | F(3,34) = 0.25 | 0.86 | 0.02 | 129 | ± | 18 | Kruskal-Wallis | X 2(3) = 3.58 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.79 | 0.13 | SMALL | |

| EB | 137 | ± | 21 | 151 | ± | 9 | 0.54 | -0.28 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 145 | ± | 10 | 179 | ± | 19 | 0.12 | -0.72 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 156 | ± | 15 | 162 | ± | 9 | 0.73 | -0.16 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Number of Nose Touch Events | Vehicle | 24 | ± | 5 | ANOVA | F(3,34) = 2.05 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 26 | ± | 3 | ANOVA | F(3,34) = 1.51 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.72 | -0.17 | SMALL | |

| EB | 21 | ± | 5 | 32 | ± | 3 | 0.05 | -0.96 | LARGE | M > F | |||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 23 | ± | 4 | 38 | ± | 5 | 0.02 | -1.17 | LARGE | M > F | |||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 33 | ± | 3 | 35 | ± | 6 | 0.80 | -0.12 | SMALL | ||||||||||

A summary of all behaviors is shown for Female (A) and Male (B) rats. Data are shown as mean + SEM, statistical tests, values and degrees of freedom, and effect sizes are indicated (SMALL = 0.01; MEDIUM = 0.09; LARGE = 0.25). No significant treatment effects were found for either sex. (C) The statistics for within-treatment sex differences and Cohen's d effect sizes for the sex differences are shown (SMALL = 0.2; MEDIUM = 0.5; LARGE = 0.8), with directionality indicated (M=male, F=female). Where there are significant differences or LARGE effect sizes, data are shown in bold text.

Social Investigation of Stimulus Animals

Each of the behaviors was subsequently analyzed for effects of treatment and sex, with the 4 stimulus rats as variables. The following analyses were conducted on the 8-minute “informed choice” period.

Time in Whole Arm (Table 3; Figure 2A)

Table 3. Time in Whole Arm (sec).

| A. Female Treatment Effects | B. Male Treatment Effects | C. Sex Effects within Treatment | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Stimulus | Treatment | Mean (s) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

Mean (s) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

P-Value | Cohen's d | Effect Size | Directionality | ||

| OS- | Vehicle | 77 | ± | 7 | ANOVA | F(3,33)=1.52 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 62 | ± | 8 | ANOVA | F(3,35)=2.76 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.66 | 0.76 | MEDIUM | |

| EB | 63 | ± | 4 | 58 | ± | 6 | 0.52 | 0.40 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 72 | ± | 4 | 82 | ± | 6 | 0.13 | -0.72 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 63 | ± | 7 | 61 | ± | 7 | 0.80 | 0.12 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| OS+ | Vehicle | 102 | ± | 12 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3)=2.37 | 0.50 | 0.07 | 96 | ± | 9 | ANOVA | F(3,35)=2.14 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.67 | 0.21 | SMALL | |

| EB | 92 | ± | 5 | 132 | ± | 9 | 0.002 | -1.58 | LARGE | M > F | |||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 111 | ± | 11 | 115 | ± | 13 | 0.80 | -0.12 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 96 | ± | 10 | 109 | ± | 8 | 0.37 | -0.43 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| SS- | Vehicle | 47 | ± | 6 | ANOVA | F(3,33)=2.27 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 64 | ± | 9 | ANOVA | F(3,36)=0.99 | 0.41 | 0.08 | 0.81 | -0.78 | MEDIUM | |

| EB | 65 | ± | 7 | 52 | ± | 7 | 0.14 | 0.61 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 64 | ± | 5 | 68 | ± | 8 | 0.69 | -0.18 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 65 | ± | 4 | 68 | ± | 7 | 0.69 | -0.18 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| SS+ | Vehicle | 86 | ± | 10 | ANOVA | F(3,32) = 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.06 | 75 | ± | 8 | ANOVA | F(3,33) = 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.44 | SMALL | |

| EB | 75 | ± | 7 | 70 | ± | 8 | 0.77 | 0.21 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 83 | ± | 6 | 83 | ± | 8 | 0.97 | 0.01 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 85 | ± | 4 | 81 | ± | 5 | 0.51 | 0.31 | SMALL | ||||||||||

Time spent in the whole arm (seconds) is shown for Females (A) and Males (B). Data here, and in subsequent Tables 4-7, are shown as mean + SEM. Statistical tests used, values and degrees of freedom, and effect sizes are indicated (SMALL = 0.01; MEDIUM = 0.09; LARGE = 0.25). (C) The statistics for within-treatment sex differences and Cohen's d effect sizes are shown (SMALL = 0.2; MEDIUM = 0.5; LARGE = 0.8) with directionality of the effect. There were no differences due to treatment. The one significant sex difference is indicated. M=male, F=female.

Regardless of sex or treatment, experimental rats spent the most time in the arm leading up to the OS+ stimulus animal. However, there were no main effects of treatment. There was one significant sex difference found for the EB groups towards the OS+ stimulus rat (male > female), with a LARGE Cohen's d effect size.

Time in Remote Arm (Table 4; Figure 2B)

Table 4. Time in Remote Arm (sec).

| A. Female Treatment Effects | B. Male Treatment Efects | C. Sex Effects within Treatment | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Stimulus | Treatment | Mean (s) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

Mean (s) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P- value |

ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

P-Value | Cohen's d | Effect Size | Directionality | ||

| OS- | Vehicle | 33 | ± | 9 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 2.06 | 0.56 | 0.06 | 45 | ± | 7 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 1.83 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.75 | 0.02 | SMALL | |

| EB | 42 | ± | 4 | 35 | ± | 10 | 0.76 | -0.19 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 46 | ± | 5 | 54 | ± | 7 | 0.80 | -0.12 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 46 | ± | 7 | 43 | ± | 5 | 0.82 | -0.11 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| OS+ | Vehicle | 63 | ± | 15 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 5.67 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 62 | ± | 7 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 4.08 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.21 | -0.38 | SMALL | |

| EB | 57 | ± | 7 | 93 | ± | 12 | 0.05 | -1.11 | LARGE | M > F | |||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 89 | ± | 12 | 95 | ± | 18 | 0.64 | 0.25 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 61 | ± | 9 | 52 | ± | 15 | 0.56 | -0.28 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| SS- | Vehicle | 21 | ± | 7 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 11.67 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 45 | ± | 6 | ANOVA | F(3,36) = 0.89 | 0.46 | 0.07 | 0.02 | -1.23 | LARGE | M > F |

| EB | 52 | ± | 7 | 36 | ± | 4 | 0.09 | 0.60 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 43 | ± | 5 | 37 | ± | 5 | 0.39 | 0.40 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 42 | ± | 3 | 45 | ± | 4 | 0.51 | -0.30 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| SS+ | Vehicle | 43 | ± | 10 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 0.0597 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 48 | ± | 9 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 2.26 | 0.48 | 0.06 | 0.63 | 0.17 | SMALL | |

| EB | 46 | ± | 5 | 37 | ± | 10 | 0.97 | -0.12 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 47 | ± | 5 | 55 | ± | 7 | 0.72 | -0.17 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1) | 38 | ± | 10 | 51 | ± | 11 | 0.13 | -0.78 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

Time spent in the remote arm (seconds) is shown with significant (p < 0.05) and/or LARGE effect sizes indicated. See Table 2 for explanations of statistics and data presentation.

Rats spent the most time in the OS+ stimulus animals' arm. In females, there was a main effect of treatment within the SS- arm, with post-hoc analysis indicating that the EB, A1221 (0.5) and A1221 (1.0) females spent significantly more time there than did the vehicle females. Regarding sex differences, a significant difference was observed in the EB group toward the OS+ stimulus animal (male > female), with a LARGE effect size. The other significant sex difference was seen in the vehicle group toward the SS- stimulus animal (male > female), again with a LARGE effect size.

Time Near Stimulus Cage (Table 5; Figure 2C)

Table 5. Time Near Stimulus Cage (sec).

| A. Female Treatment Effects | B. Male Treatment Effects | C. Sex Effects within Treatment | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Stimulus | Treatment | Mean (s) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

Mean (s) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

P-Value | Cohen's d | Effect Size | Directionality | ||

| OS- | Vehicle | 35 | ± | 7 | ANOVA | F(3,33) = 2.25 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 20 | ± | 4 | ANOVA | F(3,34) = 2.69 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.90 | LARGE | F > M |

| EB | 21 | ± | 4 | 18 | ± | 4 | 0.53 | 0.43 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 26 | ± | 4 | 32 | ± | 5 | 0.38 | -0.41 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 18 | ± | 4 | 18 | ± | 3 | 0.95 | 0.03 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| OS+ | Vehicle | 44 | ± | 8 | ANOVA | F(3,32) = 1.05 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 33 | ± | 5 | ANOVA | F(3,31) = 2.41 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.60 | MEDIUM | |

| EB | 35 | ± | 7 | 48 | ± | 4 | 0.16 | -0.48 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 27 | ± | 4 | 29 | ± | 5 | 0.78 | -0.15 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 35 | ± | 6 | 45 | ± | 7 | 0.29 | -0.49 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| SS- | Vehicle | 20 | ± | 4 | ANOVA | F(3,32) = 0.13 | 0.94 | 0.01 | 19 | ± | 5 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 3.28 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.71 | 0.07 | SMALL | |

| EB | 20 | ± | 3 | 16 | ± | 3 | 0.42 | 0.47 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 21 | ± | 5 | 31 | ± | 8 | 0.27 | -0.51 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 23 | ± | 4 | 23 | ± | 4 | 0.97 | -0.02 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| SS+ | Vehicle | 36 | ± | 9 | ANOVA | F(3,33) = 0.70 | 0.56 | 0.06 | 24 | ± | 5 | ANOVA | F(3,32) = 0.41 | 0.74 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.66 | MEDIUM | F > M |

| EB | 27 | ± | 7 | 26 | ± | 6 | 0.87 | 0.22 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 37 | ± | 6 | 31 | ± | 7 | 0.53 | 0.29 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 39 | ± | 5 | 24 | ± | 3 | 0.02 | 1.24 | LARGE | F > M | |||||||||

Time spent near (one body length) each stimulus rat's holding cage is shown with significant (p < 0.05) and/or LARGE effect sizes indicated. See Table 2 for explanations of statistics and data presentation.

There were no significant treatment effects for this measure, although there was a trend toward significance in both the males (p = 0.06) and the females (p = 0.10) for the OS- arm. Regarding sex differences, for the OS- arm, there was a LARGE effect size (female > male) although this did not attain significant. Two significant sex differences were seen for the SS+ arm for vehicle and A1221 (1.0) groups, associated with a MEDIUM and LARGE Cohen's d effect size, respectively (female > male for both).

Number of Arm Entries (Table 6; Figure 2D)

Table 6. Number of Arm Entries.

| A. Female Treatment Effects | B. Male Treatment Effects | C. Sex Effects within Treatment | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Stimulus | Treatment | Mean (#) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

Mean (#) | SEM | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

P-Value | Cohen's d | Effect size | Directionality | |||

| OS- | Vehicle | 24 | ± | 2 | ANOVA | F(3,34)=0.75 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 21 | ± | 1 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3)=7.30 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.78 | 0.56 | MEDIUM | |

| EB | 20 | ± | 1 | 17 | ± | 1 | 0.16 | 0.76 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 22 | ± | 1 | 23 | ± | 2 | 0.62 | -0.23 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 22 | ± | 2 | 24 | ± | 3 | 0.54 | -0.28 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| OS+ | Vehicle | 29 | ± | 4 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3)=1.04 | 0.79 | 0.03 | 29 | ± | 3 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3)=0.79 | 0.85 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.02 | SMALL | |

| EB | 27 | ± | 1 | 29 | ± | 3 | 0.69 | -0.18 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 31 | ± | 3 | 26 | ± | 3 | 0.27 | 0.51 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 30 | ± | 4 | 28 | ± | 3 | 0.74 | 0.15 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| SS- | Vehicle | 17 | ± | 2 | ANOVA | F(3,34)=5.12 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 19 | ± | 3 | ANOVA | X2(3)=1.37 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.61 | -0.25 | SMALL | |

| EB | 22 | ± | 2 | 17 | ± | 2 | 0.05 | 0.81 | LARGE | F > M | |||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 22 | ± | 1 | 19 | ± | 3 | 0.21 | 0.58 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 27 | ± | 2 | 23 | ± | 2 | 0.16 | 0.65 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| SS+ | Vehicle | 26 | ± | 3 | ANOVA | F(3,34)=0.23 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 21 | ± | 1 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3)=3.09 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.71 | MEDIUM | |

| EB | 25 | ± | 2 | 23 | ± | 2 | 0.65 | 0.28 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 27 | ± | 2 | 24 | ± | 3 | 0.45 | 0.35 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 26 | ± | 1 | 26 | ± | 2 | 0.93 | -0.04 | SMALL | ||||||||||

The mean number of entries into each of the arms is shown with significant (p < 0.05) and/or LARGE effect sizes indicated. See Table 2 for explanations of statistics and data presentation.

All treatment groups entered the arm containing the OS+ stimulus animal most often. A main effect of treatment was seen in females for the SS- arm, driven by a significantly higher number of entries for the A1221 (1.0) females entered the arm compared to females in the vehicle group. There were no main effects of treatment in males. There was one instance of a significant sex difference for EB rats with respect to the SS- stimulus (female > male); this difference was associated a LARGE effect size.

Number of Stimulus Explore Events (Table 7; Figure 2E)

Table 7. Number of Stimulus Explore Events.

| A. Female Treatment Effects | B. Male Treatment Effects | C. Sex Effects within Treatment | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Stimulus | Treatment | Mean (#) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

Mean (#) | SEM | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

P-Value | Cohen's d | Effect size | Directionality | |||

| OS- | Vehicle | 36 | ± | 9 | ANOVA | F(3,34) = 0.18 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 24 | ± | 5 | ANOVA | F(3,33) = 4.13 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.80 | 0.58 | MEDIUM | |

| EB | 34 | ± | 6 | 26 | ± | 4 | 0.55 | 0.50 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 35 | ± | 4 | 47 | ± | 6 | 0.15 | -0.68 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 33 | ± | 6 | 31 | ± | 5 | 0.83 | 0.10 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| OS+ | Vehicle | 44 | ± | 8 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 1.37 | 0.71 | 0.04 | 45 | ± | 7 | ANOVA | F(3,35) = 1.41 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.83 | -0.06 | SMALL | |

| EB | 46 | ± | 2 | 65 | ± | 5 | 0.01 | -1.61 | LARGE | M > F | |||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 47 | ± | 5 | 60 | ± | 11 | 0.29 | -0.52 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 52 | ± | 6 | 69 | ± | 10 | 0.17 | -0.63 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| SS- | Vehicle | 26 | ± | 6 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 5.15 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 32 | ± | 3 | ANOVA | F(3,34) = 1.83 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.69 | -0.42 | MEDIUM | |

| EB | 37 | ± | 3 | 25 | ± | 3 | 0.03 | 1.31 | LARGE | F > M | |||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 25 | ± | 2 | 35 | ± | 4 | 0.03 | -1.12 | LARGE | M > F | |||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 33 | ± | 5 | 33 | ± | 2 | 0.97 | 0.02 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| SS+ | Vehicle | 36 | ± | 8 | ANOVA | F(3,32) = 0.39 | 0.76 | 0.04 | 39 | ± | 5 | ANOVA | F(3,34) = 0.43 | 0.73 | 0.04 | 0.84 | -0.13 | SMALL | |

| EB | 42 | ± | 8 | 37 | ± | 4 | 0.95 | 0.23 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 45 | ± | 7 | 44 | ± | 5 | 0.87 | 0.07 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 43 | ± | 5 | 40 | ± | 4 | 0.67 | 0.20 | SMALL | ||||||||||

The mean number of stimulus explore events is shown with significant (p < 0.05) and/or LARGE effect sizes indicated. See Table 2 for explanations of statistics and data presentation.

For all treatments and both sexes, the number of times the experimental animal explored the stimulus cage was highest toward the OS+ animal. No effects of treatment were seen in females. A main effect of treatment was observed in the males towards the OS- stimulus rats, with post-hoc analysis showing A1221 (0.5) > vehicle and EB. Several main effects of sex were observed. Compared to EB females, EB males explored the OS+ stimulus significantly more; this difference was associated with a LARGE effect size. With respect to the SS- stimulus, a main effect of sex was found for the EB (female > male) and A1221 (0.5) (male > female). The Cohen's d effect sizes associated with these differences were both LARGE.

Number of Nose Touch Events (Table 8; Figure 2F)

Table 8. Number of Nose Touch Events.

| A. Female Treatment Effects | B. Male Treatment Effects | C. Sex Effects within Treatment | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Stimulus | Treatment | Mean (#) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

Mean (#) | SEM | Test | F (df) for ANOVA; X2 (df) for KW |

P-value | ηp2 for ANOVA; ε2 for KW |

P-Value | Cohen's d | Effect size | Directionality | ||

| OS- | Vehicle | 6.8 | ± | 2.1 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 1.42 | 0.70 | 0.04 | 5.8 | ± | 2.2 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 4.43 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.15 | SMALL | |

| EB | 4.4 | ± | 1.2 | 7.3 | ± | 1.9 | 0.23 | -0.55 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 6.3 | ± | 1.2 | 10.0 | ± | 1.6 | 0.09 | -0.81 | LARGE | M > F | |||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 6.8 | ± | 1.9 | 4.9 | ± | 1.3 | 0.43 | 0.38 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| OS+ | Vehicle | 9.8 | ± | 2.4 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 4.08 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 11.6 | ± | 3.2 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 1.90 | 0.59 | 0.05 | 0.06 | -0.21 | SMALL | |

| EB | 7.8 | ± | 2.5 | 14.3 | ± | 1.8 | 0.01 | -0.64 | MEDIUM | M > F | |||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 10.3 | ± | 2.4 | 14.3 | ± | 2.5 | 0.26 | -0.55 | MEDIUM | ||||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 14.4 | ± | 2.4 | 17.1 | ± | 3.9 | 0.56 | -0.26 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| ss- | Vehicle | 3.4 | ± | 1.6 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 3.67 | 0.30 | 0.11 | 4.1 | ± | 1.0 | ANOVA | F(3,33) = 1.30 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.18 | -0.19 | SMALL | |

| EB | 1.9 | ± | 0.8 | 3.0 | ± | 0.6 | 0.22 | -0.29 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 2.4 | ± | 0.6 | 5.7 | ± | 1.0 | 0.01 | -1.34 | LARGE | M > F | |||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 5.0 | ± | 1.3 | 4.4 | ± | 1.2 | 0.77 | 0.14 | SMALL | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| SS+ | Vehicle | 4.3 | ± | 1.6 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 2.67 | 0.45 | 0.08 | 5.3 | ± | 1.1 | Kruskal-Wallis | X2(3) = 3.73 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.09 | -0.26 | SMALL | |

| EB | 7.9 | ± | 2.3 | 8.2 | ± | 1.7 | 0.92 | 0.03 | SMALL | ||||||||||

| A1221 (0.5) | 5.0 | ± | 1.4 | 10.1 | ± | 2.1 | 0.06 | -0.90 | LARGE | M > F | |||||||||

| A1221 (1.0) | 7.6 | ± | 1.2 | 9.1 | ± | 1.7 | 0.48 | -0.33 | SMALL | ||||||||||

The mean number of nose touch events is shown with significant (p < 0.05) and/or LARGE effect sizes indicated. See Table 2 for explanations of statistics and data presentation.

The OS+ stimulus animals again elicited the greatest number of nose touches, and there were no main effects of treatment in either sex. There were several sex differences, all male > female, as indicated by p-values and/or LARGE effect sizes. Specifically, sex differences were found for the OS- stimulus [A1221 (0.5)] for the OS+ stimulus (EB); and for both the SS- and the SS+ stimuli [A1221 (0.5)].

Multivariate Analyses of Behavior

Principle components analysis and linear discriminate analysis

In females, PCA determined that 53% of the variance could be accounted for within the first 3 principle components (Supplemental Figure S1A). Linear discriminate analysis (Supplemental Table S1) revealed that the EB and vehicle datasets differed from each other significantly within females. In males, again, PCA determined that 53% of the variance could be accounted for within the first 3 principle components (Supplemental Figure S1B). There were no effects of treatment found on the datasets within the males. When the sexes were considered together, female EB and male EB rats also differed (Supplemental Table S1).

Functional Landscape Analysis of Behaviors for Sex Differences

Two variables, Time in Whole Arm and Number of Nose Touch Events were further analyzed by landscape analysis, chosen because the first represents an initial exploratory act in evaluating a conspecific (similar to appetitive behaviors in mating), and the second representing the most active engagement allowed animals (closest to the consummatory act). For Time in Whole Arm (Figure 3)there was a significant effect of sex for the EB group, with the female and male landscape profiles differing significantly (p <0.002). The other 3 treatment groups did not differ by sex. For the Number of Nose Touch Events, similar analysis revealed that the A1221 (0.5) group was the only one with a significant sex difference (p < 0.05; Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Time Spent in the Whole Arm, an appetitive behavior, is shown for females (left), males (middle), and the sex difference (right) as functional landscapes. For each sex, the height of each peak shows the absolute amount of time spent in the arm (seconds). For the sex difference, the y-axis shows the time differential, with an upward peak indicating F > M, and a downward valley indicating M > F.The only landscape profile that differed significantly between the sexes was the EB group. The positions of the four stimulus choices in each landscape are indicated by the inset.

Figure 4.

Number of Nose Touch Events (consummatory behavior) is shown for females (left), males (center), and the sex difference (right). Labels and analysis are the same as in Figure 3.A sex difference was found only for the A1221 (0.5) group.

Discussion

The concept that the EDCs are one of a number of potent environmental stressors has been gaining traction (Grandjean et al., 2015; Padmanabhan, Cardoso, & Puttabyatappa, 2016). The effects of these chemicals must be put in the broader context of the anthropogenic, natural, and social environments. Our focus on how prenatal PCB exposures change the trajectory of development adds to knowledge about a subset of these types of interactions, with an emphasis on evaluating outcomes in a more socially-relevant system. This study adds to the small but growing body of literature showing social behavior can be altered through developmental exposure to these PCBs (Jolous-Jamshidi, Cromwell, McFarland, & Meserve, 2010; Bell et al., 2015).

Effects of Prenatal PCBs on Biological and Social Outcomes in the FourPlex

In nature, individuals differ by sex, reproductive status, age, and dominance hierarchy, among other traits. Rats are social animals living in communal settings with conspecifics of both sexes, a range of ages, health, and experiences. By expanding from the traditional two-choice to a four-choice test, we can systematically investigate the influence of more than one biologically-relevant factor on an experimental animal's social decision-making. In our apparatus, the experimental animal engages in motivated behavior, presumably driven by a desire to increase or decrease the distance between themselves and a stimulus animal. The choice to spend time near one stimulus is also inversely related to time away from other stimulus animals. Observing these behaviors within the context of endocrine disruption due to PCBs enables us to better understand how low dose exposure to these compounds can lead to functional behavioral changes in adulthood.

In our study, there were no significant morphological differences observed throughout the development of these animals, consistent with prior work on similarly-treated animals (Gillette et al., 2017; Reilly et al., 2015). Thus, any alterations in behavior of these animals are likely not due to changes in the animal's health. In general, our results further show that irrespective of prenatal treatment, the experimental rats spent more time in parts of the apparatus in association with the OS+ stimulus animal. This result is consistent with the literature in two-choice models of a choice between same sex conspecifics of differing hormonal status: males prefer estrous (or estrogen-treated) females over non-estrous (or ovariectomized) females, and females prefer males with testosterone over castrated males (Xiao, Kondo, and Sakuma, 2004). Similarly, when presented with an opposite-sex binary choice, males prefer females, and females prefer males (Bakker, 2003; Carson, 2003; Henley, Nunez, & Clemens, 2011). Thus, the FourPlex is a sensitive tool for differentiating amongst multiple stimuli in a manner consistent with simpler systems.

Although the patterns of behavior in the FourPlex were largely preserved across prenatal treatment groups, there were several small but significant effects of prenatal treatment when considered in relationship to specific stimulus rats. These are best viewed in Table 9, which summarizes significant differences and/or LARGE effect sizes for treatment effects. In females, the only overall treatment effects were in the SS- arm (i.e. towards ovariectomized females): time spent in the remote part of the arm, and number of arm entries, was greater in EDC-exposed (especially A1221 (1.0)) than in vehicle females. We interpret this to mean that there is increased likelihood of the EDC females to affiliate with what is normally the least-salient stimulus. For males, the only significant treatment effect was towards the OS- animal (ovariectomized female), limited to the number of stimulus explore events. In this case, A1221 (0.5) males had increased exploration compared to vehicle and EB rats. Although not significant, there was a trend (p = 0.06) for these animals to spend more time near the OS- rat's cage, and in the whole arm of that rat. It is noteworthy that the perception of and/or interaction with the ovariectomized female stimulus rat was the only one affected by treatment in both sexes. Finally, for experimental males in relationship to the OS+ rats (ovariectomized female plus estradiol) there were trends for total time, and time near the stimulus rat's cage, to be greater in EB than vehicle males. Thus, although wholesale behavioral changes were not caused by prenatal treatments, there are subtle shifts in interactions revealed in the FourPlex. While we do not know the mechanisms for these EDC effects, the finding that A1221 and EB have differential outcomes suggests that the former compound is acting by a non-estrogenic pathway. Furthermore, we point out that the prenatal EB treatment did not masculinize feminine behaviors, nor feminize masculine behavior. This is not unexpected given the low dose of EB and the short duration of treatment; in fact, our prior studies (Dickerson, Cunningham, & Gore, 2011; Steinberg, Walker, Juenger, Woller, & Gore, 2008; Walker, Goetz, & Gore, 2013; Gillette et al., 2017; Reilly et al., 2015) are consistent with the current finding of small EB effects on brain and behavior in this model.

Table 9. Summary of treatment effects and sex differences in the FourPlex.

| Behavior | Female Treatment Effects | Male Treatment Effects | Sex Difference | Directionality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Time in Whole Arm | OS+ (EB) | M > F | ||

|

| ||||

| Time in Remote Arm | SS- (vehicle < EB, A1221 (0.5), A1221 (1.0)) | OS+ (EB) | M > F | |

| SS- (vehicle) | M > F | |||

|

| ||||

| Time Near Stimulus Cage | OS- (vehicle) | F > M | ||

| SS+ (vehicle) | F > M | |||

| SS+ (A1221 (1.0)) | F > M | |||

|

| ||||

| Number of Arm Entries | SS- (vehicle < A1221 (1.0)) | SS- (EB) | F > M | |

|

| ||||

| Number of Stimulus Explore Events | OS- (vehicle, EB < A1221 (0.5)) | OS+ (EB) | M > F | |

| SS- (EB) | F > M | |||

| SS- (A1221 (0.5)) | M > F | |||

|

| ||||

| Number of Nose Touch Events | OS- (A1221 (0.5)) | M > F | ||

| OS+ (EB) | M > F | |||

| SS- (A1221 (0.5)) | M > F | |||

| SS+ (A1221 (0.5)) | M > F | |||

Results of all measures in the FourPlex are shown for significant (p < 0.05) and/or LARGE effect sizes.

Prenatal EDCs Exacerbate Sex Differences in Behaviors

The sexual dimorphism in behaviors in the FourPlex, or lack thereof, were influenced by prenatal EDC exposures (Table 9). When considering the OS+ rats – the most socially salient stimulus that was preferred by both sexes – prenatal EB treatment introduced a novel sexual dimorphism, with males spending more time in the whole arm, time in the remote arm, and engaging in more stimulus explore and nose touch events. Sex differences and similarities in behaviors toward the SS- animal were the second-most commonly observed. For the number of stimulus explore and nose touch events, A1221 (0.5) treatment resulted in males having greater numbers of these events than females. In addition, numbers of stimulus explore events and arm entries toward the SS- rat was greater in EB females than males. The time spent in the remote portion of the SS- arm was only sexually dimorphic in the vehicle group. As for the SS+ group, a sex difference in time near the stimulus cage was found for vehicle and A1221 (1.0) rats (female > male) but not for the EB or A1221 (0.5) groups.

It is notable that most of these effects are in relationship to the OS+ and SS- groups, as these differ most in sociosexual valence. This underscores that the sensitivity of the FourPlex to discriminate the hierarchy of preference in rats is greatest for a hormonally-treated (or potentially gonadally intact) opposite sex rat, and lowest for a same-sex hormonally-deficient rat.

FourPlex Results do not Mirror the Binary Choice Paradigm

It is informative to consider the results for the vehicle group vis-à-vis validation of the FourPlex in control animals. For both sexes, the numbers of arm entries, time spent, and interactions with (especially nose touches) stimulus rats were highest toward the opposite-sex, hormone-treated rat. This result, while not surprising, shows that the layout of the apparatus is adequate for a rat to discriminate, and for an investigator to discern that discrimination in a 10-minute trial.

It is also informative to contrast the current results to those of our prior binary choice study, in which rats received identical treatments to those used here, but were tested differently in adulthood (Reilly et al., 2015). There, rats were given the opportunity to distinguish between two same-sex gonadectomized rats (no hormone), one familiar and one unfamiliar. Under those conditions, while all experimental rats showed the expected preference for a novel over a familiar rat, the differential was much greater in males than females, with the exception of the male A1221 (0.5) group. These animals were more similar in their behaviors to the females, showing a loss of the sexual dimorphism. By contrast, sex differences in the FourPlex arena were more likely to have an exaggerated dimorphism with treatment. Moreover, the magnitudes of changes in the FourPlex were, in general, smaller than in the two-choice test, suggesting a tempering of the outcomes in a more complex social setting.

Ethological Implications

It has been a long-lasting endeavor to balance ethological significance and experimental feasibility when studying behavior in laboratory animals. In practice, controlling the environment in dyadic choice models is favored over settings more representative of an animal's natural habitat due to the greater ease in simplifying behaviors in the former over the latter. However, advancements in technology have greatly aided efforts in creating environments capable of providing animals with more naturalistic setting. In particular, systems that allow for the automatic tracking of individual animals within a multi-animal, free-roaming environment have provided unique insights into the social hierarchy organization in a mouse model (So et al., 2015; Weissbrod et al., 2013). Automatic scoring of behaviors within such paradigms provide means of discovering novel and objective metrics of social behavior. Hong et al. used a simultaneous video and depth camera setup in combination with computerized vision and supervised machine learning methods to gain unprecedented resolution (30 frames/second) of social interaction behavior between two strains of mice. This allowed the detection of extremely subtle differences in bout-length investigation previously undetectable through more standard methods (Hong et al., 2015).

It is notable that work in other fields have, on occasion, utilized 4+ choice paradigms. For example, a study on the effects of amphetamines on rat social behavior revealed that both treated and control rats would augment their aggregative tendency in proportion to the number of stimulus rats within the behavioral apparatus (Heimstra & McDonald, 1962). Studies on mate preference in rats have provided a female rat with four males and revealed differences in the dynamics of sexual selection when compared to binary choice models (Ferreira-Nuño et al., 2005). The field of cognitive neuroscience has many examples of learning-based tasks in radial arm mazes with multiple choices (Witty, Foster, Semple-Rowland, & Daniel, 2012), although in most cases the stimuli are objects or food rather than conspecifics. Nevertheless, the importance of mimicking the more realistic situation of multiple rather than binary possibilities underscores the potential application of the FourPlex to studies on endocrine disruption and other environmental perturbations.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure S1. Correlation plots derived from analysis of the first three principle components are shown for females (A) and males (B). These principle components, accounting for 53% of variance in both sexes, were derived from the analysis of the entire ethogram, with behaviors indicated on the y-axis. Along with those behaviors discussed elsewhere in the manuscript, behaviors relative to the center of the chamber are indicated with reference to the full center area (labeled “3” in Figure 1) or an innermost center (labeled “4” in Figure 1). For each measure listed on the vertical axis, the bar displays the magnitude and direction of correlation (loading) on each of the principle components 1-3, expressed as a correlation coefficient on the horizontal axes. Bars in the same direction indicate measures that correlate together. The dashed line indicates a threshold beyond which any measure can be stated to significantly influence each principle component, defined as one half the absolute value of the largest loading.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Ross Gillette for assistance with statistical analyses.

Funding: NIH 1RO1 ES023254, NIH 1RO1 ES020662

References cited

- Bakker J. Sexual differentiation of the neuroendocrine mechanisms regulating mate recognition in mammals. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2003;15(6):615–621. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MR, Thompson LM, Rodriguez K, Gore AC. Two-hit exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls at gestational and juvenile life stages: 1. Sexually dimorphic effects on social and anxiety-like behaviors. Hormones and Behavior. 2015;78:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni V, Dessì-Fulgheri F, Zaccaroni M, Di Consiglio E, De Angelis G, Testai E, Santochirico M, Alleva E, Santucci D. Early exposure to low doses of atrazine affects behavior in juvenile and adult CD1 mice. Toxicology. 2011;279:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson HL. Mate choice theory and the mode of selection in sexual populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(11):6584–6587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0732174100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews D, Gillette R, Scarpino SV, Manikkam M, Savenkova MI, Skinner MK. Epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of altered stress responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(24):9143–9148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118514109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews D, Gore AC. Life imprints: Living in a contaminated world. Environmental Health Perspective. 2011;119(9):1208–1210. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews D. Neural Control of Sexual Behavior. In: Breed MD, Moore J, editors. Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior. Academic Press; Oxford; 2010. pp. 541–548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EC, Popper P, Gorski RA. The role of apoptosis in sexual differentiation of the rat sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area. Brain Research. 1996;734:10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKoning EP, Karmaus W. PCB exposure in utero and via breast milk. A review. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology. 2000;10(3):285–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SM, Cunningham SL, Gore AC. Prenatal PCBs disrupt early neuroendocrine development of the rat hypothalamus. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2011;252:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Nuño A, Morales-Otal A, Paredes RG, Velázquez-Moctezuma J. Sexual behavior of female rats in a multiple-partner preference test. Hormones and Behavior. 2005;47(3):290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillette R, Miller-Crews I, Nilsson EE, Skinner MK, Gore AC, Crews D. Sexually dimorphic effects of ancestral exposure to vinclozolin on stress reactivity in rats. Endocrinology. 2014;155(10):3853–3866. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillette R, Reilly MP, Topper VY, Thompson LM, Crews D, Gore AC. Anxiety-like behaviors in adulthood are altered in male but not female rats exposed to low dosages of polychlorinated biphenyls in utero. Hormones and Behavior. 2017;87:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladen BC, Doucet J, Hansen LG. Assessing human polychlorinated biphenyl contamination for epidemiologic studies: Lessons from patterns of Congener concentrations in Canadians in 1992. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2003;111(4):437–443. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Barouki R, Bellinger DC, Casteleyn L, Chadwick LH, Cordier S, et al. Heindel JJ. Life-long implications of developmental exposure to environmental stressors: New perspectives. Endocrinology. 2015;156(10):3408–3415. doi: 10.1210/EN.2015-1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimstra NW, McDonald AL. Social Influence on the Reponse to Drugs: IV. Stimulus Factors. The Psychological Record. 1962;12:383–386. [Google Scholar]

- Henley CL, Nunez AA, Clemens LG. Hormones of choice: The neuroendocrinology of partner preference in animals. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2011;32(2):146–164. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong W, Kennedy A, Burgos-Artizzu XP, Zelikowsky M, Navonne SG, Perona P, Anderson DJ. Automated measurement of mouse social behaviors using depth sensing, video tracking, and machine learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112(38):E5351–E5360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515982112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huck UW, Lisk RD, Gore AC. Scent marking and mate choice in the golden hamster. Physiology & Behavior. 1985;35(3):389–93. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(85)90314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson CD, Shryne JE, Shapiro F, Gorski RA. Ontogeny of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1980;193:541–548. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolous-Jamshidi B, Cromwell HC, McFarland AM, Meserve LA. Perinatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls alters social behaviors in rats. Toxicology Letters. 2010;199:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Pessah IN, Puschner B. Simultaneous determination of polybrominated diphenyl ethers and polychlorinated biphenyls by gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry in human serum and plasma. Talanta. 2013;113:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Arnold AP. Reframing sexual differentiation of the brain. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14(6):677–83. doi: 10.1038/nn.2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock MK. A functional approach to the behavioral endocrinology of rodents. In: Crews D, editor. Psychobiology of Reproductive Behavior: An Evolutionary Perspective. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, N.J: 1987. pp. 26–60. [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan V, Cardoso RC, Puttabyatappa M. Developmental programming, a pathway to disease. Endocrinology. 2016;157(4):1328–1340. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly MP, Weeks CD, Topper VY, Thompson LM, Crews D, Gore AC. The effects of prenatal PCBs on adult social behavior in rats. Hormones and Behavior. 2015;73(3):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpino SV, Gillette R, Crews D. multiDimBio: An R Package for the Design, Analysis, and Visualization of Systems Biology Experiments. Quantitative Methods. 2014 https://arxiv.org/abs/1404.0594v1.

- So N, Franks B, Lim S, Curley JP. Associations between Mouse Social Dominance and Brain Gene Expression. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0134509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg RM, Juenger TE, Gore AC. The effects of prenatal PCBs on adult female paced mating reproductive behaviors in rats. Hormones and Behavior. 2007;51:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg RM, Walker DM, Juenger TE, Woller MJ, Gore AC. Effects of perinatal polychlorinated biphenyls on adult female rat reproduction: development, reproductive physiology, and second generational effects. Biology of Reproduction. 2008;78:1091–1101. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.067249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi Y, Aburada S, Hashimoto K, Kitaura T. Transfer and distribution of accumulated (14C) polychlorinated biphenyls from maternal to fetal and suckling rats. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 1986;15(6):709–715. doi: 10.1007/bf01054917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Bielsky IF, Ross HE, Kawamata M, Onaka T, et al. Nishimori K. Pervasive social deficits, but normal parturition, in oxytocin receptor-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102:16096–16101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505312102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topper VY, Walker DM, Gore AC. Sexually dimorphic effects of gestational endocrine-disrupting chemicals on microRNA expression in the developing rat hypothalamus. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2015;414:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venerosi A, Ricceri L, Tait S, Calamandrei G. Sex dimorphic behaviors as markers of neuroendocrine disruption by environmental chemicals: The case of chlorpyrifos. NeuroToxicology. 2012;33:1420–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DM, Goetz BM, Gore AC. Dynamic postnatal developmental and sex-specific neuroendocrine effects of prenatal PCBs in rats. Molecular Endocrinology 28(1) 2013:99–115. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Walker DM, Kirson D, Perez LF, Gore AC. Molecular profiling of postnatal development of the hypothalamus in female and male rats. Biology of Reproduction. 2012;87:129. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.102798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissbrod A, Shapiro A, Vasserman G, Edry L, Dayan M, Yitzhaky A, et al. Kimchi T. Automated long-term tracking and social behavioural phenotyping of animal colonies within a semi-natural environment. Nature Communications. 2013;4:2018. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witty CF, Foster TC, Semple-Rowland SL, Daniel JM. Increasing Hippocampal Estrogen Receptor Alpha Levels via Viral Vectors Increases MAP Kinase Activation and Enhances Memory in Aging Rats in the Absence of Ovarian Estrogens. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolstenholme JT, Taylor JA, Shetty SR, Edwards M, Connelly JJ, Rissman EF. Gestational exposure to low dose bisphenol a alters social behavior in juvenile mice. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e25448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure S1. Correlation plots derived from analysis of the first three principle components are shown for females (A) and males (B). These principle components, accounting for 53% of variance in both sexes, were derived from the analysis of the entire ethogram, with behaviors indicated on the y-axis. Along with those behaviors discussed elsewhere in the manuscript, behaviors relative to the center of the chamber are indicated with reference to the full center area (labeled “3” in Figure 1) or an innermost center (labeled “4” in Figure 1). For each measure listed on the vertical axis, the bar displays the magnitude and direction of correlation (loading) on each of the principle components 1-3, expressed as a correlation coefficient on the horizontal axes. Bars in the same direction indicate measures that correlate together. The dashed line indicates a threshold beyond which any measure can be stated to significantly influence each principle component, defined as one half the absolute value of the largest loading.