Abstract

Aflatoxins and ochratoxins are among the most important mycotoxins of all and producers of both types of mycotoxins are present in Aspergillus section Flavi, albeit never in the same species. Some of the most efficient producers of aflatoxins and ochratoxins have not been described yet. Using a polyphasic approach combining phenotype, physiology, sequence and extrolite data, we describe here eight new species in section Flavi. Phylogenetically, section Flavi is split in eight clades and the section currently contains 33 species. Two species only produce aflatoxin B1 and B2 (A. pseudotamarii and A. togoensis), and 14 species are able to produce aflatoxin B1, B2, G1 and G2: three newly described species A. aflatoxiformans, A. austwickii and A. cerealis in addition to A. arachidicola, A. minisclerotigenes, A. mottae, A. luteovirescens (formerly A. bombycis), A. nomius, A. novoparasiticus, A. parasiticus, A. pseudocaelatus, A. pseudonomius, A. sergii and A. transmontanensis. It is generally accepted that A. flavus is unable to produce type G aflatoxins, but here we report on Korean strains that also produce aflatoxin G1 and G2. One strain of A. bertholletius can produce the immediate aflatoxin precursor 3-O-methylsterigmatocystin, and one strain of Aspergillus sojae and two strains of Aspergillus alliaceus produced versicolorins. Strains of the domesticated forms of A. flavus and A. parasiticus, A. oryzae and A. sojae, respectively, lost their ability to produce aflatoxins, and from the remaining phylogenetically closely related species (belonging to the A. flavus-, A. tamarii-, A. bertholletius- and A. nomius-clades), only A. caelatus, A. subflavus and A. tamarii are unable to produce aflatoxins. With exception of A. togoensis in the A. coremiiformis-clade, all species in the phylogenetically more distant clades (A. alliaceus-, A. coremiiformis-, A. leporis- and A. avenaceus-clade) are unable to produce aflatoxins. Three out of the four species in the A. alliaceus-clade can produce the mycotoxin ochratoxin A: A. alliaceus s. str. and two new species described here as A. neoalliaceus and A. vandermerwei. Eight species produced the mycotoxin tenuazonic acid: A. bertholletius, A. caelatus, A. luteovirescens, A. nomius, A. pseudocaelatus, A. pseudonomius, A. pseudotamarii and A. tamarii while the related mycotoxin cyclopiazonic acid was produced by 13 species: A. aflatoxiformans, A. austwickii, A. bertholletius, A. cerealis, A. flavus, A. minisclerotigenes, A. mottae, A. oryzae, A. pipericola, A. pseudocaelatus, A. pseudotamarii, A. sergii and A. tamarii. Furthermore, A. hancockii produced speradine A, a compound related to cyclopiazonic acid. Selected A. aflatoxiformans, A. austwickii, A. cerealis, A. flavus, A. minisclerotigenes, A. pipericola and A. sergii strains produced small sclerotia containing the mycotoxin aflatrem. Kojic acid has been found in all species in section Flavi, except A. avenaceus and A. coremiiformis. Only six species in the section did not produce any known mycotoxins: A. aspearensis, A. coremiiformis, A. lanosus, A. leporis, A. sojae and A. subflavus. An overview of other small molecule extrolites produced in Aspergillus section Flavi is given.

Key words: Aspergillus, Section Flavi, Aflatoxins, Cyclopiazonic acid, Tenuazonic acid

Taxonomic novelties: Aspergillus aflatoxiformans Frisvad, Ezekiel, Samson & Houbraken, Aspergillus aspearensis Houbraken, Frisvad, Arzanlou & Samson, Aspergillus austwickii Frisvad, Ezekiel, Samson & Houbraken, Aspergillus cerealis Houbraken, Frisvad, Ezekiel & Samson, Aspergillus neoalliaceus A. Nováková, Hubka, Samson, Frisvad & Houbraken, Aspergillus pipericola Frisvad, Samson & Houbraken, Aspergillus subflavus Hubka, A. Nováková, Samson, Frisvad & Houbraken, A. vandermerwei Frisvad, Hubka, Samson & Houbraken

Introduction

Aspergillus subgenus Circumdati section Flavi contains some of the most important species in the genus, which are of significance in biotechnology, foods and health (Varga et al. 2011). Aspergillus flavus is reported, after A. fumigatus (section Fumigati), as the second leading cause of invasive aspergillosis and it is the most common cause of superficial infection (Hedayati et al. 2007). Aspergillus oryzae and A. sojae appear to be the domesticated forms of the aflatoxigenic species A. flavus and A. parasiticus, respectively, and are used extensively in the food and biotechnology industries (Houbraken et al. 2014). A large number of species in Aspergillus section Flavi are common in crops, and some of them produce several mycotoxins, such as aflatoxins, 3-nitropropionic acid, tenuazonic acid and cyclopiazonic acid (Varga et al. 2011). Despite many publications in various research fields, the taxonomy of the aflatoxigenic species in Aspergillus section Flavi is still not fully elucidated, and several new species (some with aflatoxigenic potential) have been described since 2011, such as A. novoparasiticus (Gonçalves et al., 2012a, Gonçalves et al., 2012b), A. mottae, A. transmontanensis, A. sergii (Soares et al. 2012), A. bertholletius (Taniwaki et al. 2012), A. hancockii (Pitt et al. 2017) and A. korhogoensis (Carvajal-Campos et al. 2017). Additionally, there have also been some disagreements on the proper species names of strains formerly identified as A. flavus with large or small sclerotia (Probst et al., 2012, Probst et al., 2014).

Initially, A. flavus was reported to produce aflatoxin of the B and G type (Nesbitt et al., 1962, Codner et al., 1963). Later it was recognised that strains of A. flavus can only produce aflatoxin B1 and B2 (Varga et al., 2009, Amaike and Keller, 2011) and that the strains producing aflatoxin B and G were A. parasiticus, exemplified by strain NRRL 2999, which was initially identified as A. flavus (Christensen et al. 1973) and three years later re-identified as A. parasiticus (Buchanan & Ayres 1976). Although it was considered that A. flavus only produces B type aflatoxins, some reports indicate that A. flavus strains can also produce the G type aflatoxins (Camiletti et al., 2017, Barayani et al., 2015, Wicklow and Shotwell, 1983, Okoth et al., 2018, Saldan et al., 2018). This contradictory data needs further investigation and it is important to determine whether A. flavus sensu stricto can produce aflatoxins of the G type or not. Most species in Aspergillus section Flavi produce both types of aflatoxins, while species outside section Flavi can only accumulate sterigmatocystin and aflatoxins of the B type (Geiser et al., 2007, Varga et al., 2009, Rank et al., 2011).

Raper & Fennell (1965) stated that A. flavus strains produced globose to subglobose sclerotia that are normally 400–700 μm in size, rarely exceeding 1 mm, but that some strains produced sclerotia that were uniformly and consistently smaller. They also mentioned strains that produced vertically elongate sclerotia, and such strains were later shown to be A. nomius or A. pseudonomius (Kurtzman et al. 1997, Varga et al., 2011, Massi et al., 2014). Also Hesseltine et al. (1970) reported A. flavus isolates with small sclerotia while most isolates had large sclerotia. They listed NRRL 3251 as one of the rare examples of a strain with small sclerotia that produced aflatoxin B1 and B2 only, and stated that this could represent a new species. Another strain similar to NRRL 3251 that also produce small-sized sclerotia is the genome sequenced strain ATCC MYA384 (= AF70) (Moore et al. 2015). These A. flavus strains with small sclerotia that produce B type aflatoxins (A. flavus SB) are more common in USA than in Africa (Probst et al. 2014). Later Saito & Tsuruta (1993) found many strains with small sclerotia from agricultural soil in Thailand. They described their strains and NRRL 3251 as A. flavus var. parvisclerotigenus. In 2005, Frisvad et al. (2005) raised A. flavus var. parvisclerotigenus to species level and neotypified the species with a strain isolated from a peanut in Nigeria producing aflatoxin B1, B2, G1 and G2 (CBS 121.62 = IMI 093070 = NRRL A-11612). This neotypification is questionable as the original type only produced B type aflatoxins. Other strains producing small sclerotia, often referred to as A. flavus group SBG (= “A. flavus strains producing small sized sclerotia and aflatoxin B and G”) represent multiple species. One of the “A. flavus group SBG” taxa was described as A. minisclerotigenes (from Argentina originally) (Pildain et al. 2008) and is also found in Central, East and Southern Africa and Australia (Probst et al. 2014), while A. parvisclerotigenus sensu Frisvad et al. (2005) has been found in West Africa: Benin, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Senegal and Sierra Leone (Probst et al. 2014). Another important group of strains is identified as A. flavus SB and these strains are regarded as the agent causing lethal levels of aflatoxins in Kenyan maize. It remains questionable whether these are truly A. flavus or that these strains represent a species that has not yet been named (Cotty and Cardwell, 1999, Cardwell and Cotty, 2002, Donner et al., 2009, Okoth et al., 2012, Okoth et al., 2018, Probst et al., 2007, Probst et al., 2010, Probst et al., 2012, Probst et al., 2014). However, a later study shows A. flavus sensu stricto and A. minisclerotigenes are the predominant species in Kenyan maize (Okoth et al. 2018).

The genomes of A. oryzae RIB 40 (Machida et al., 2005, Galagan et al., 2005, Inglis et al., 2013, Umemura et al., 2013a, Umemura et al., 2013b), and other strains of A. oryzae (Zhao et al., 2012, Zhao et al., 2013, Zhao et al., 2014), A. flavus NRRL 3357 (= ATCC 200026) (Payne et al., 2006, Fedorova et al., 2008, Nierman et al., 2015), ATCC MYA384 (= AF70) (Moore et al. 2015) and other strains (Faustinelli et al. 2016), A. parasiticus ATCC 56775 (= NRRL 5862 = SU-1) (Linz et al. 2014), A. sojae NBRC 4239 (Sato et al. 2011), A. bombycis NRRL 26010 (Moore et al. 2016), A. nomius NRRL 13137 (= NBRC 33223) (Horn et al., 2009c, Moore et al., 2015), A. hancockii FRR 3425 (Pitt et al. 2017) and A. arachidicola (Moore et al. 2018) have been published. Gene clusters for several secondary metabolites, and the regulation of these gene clusters in A. flavus are known, including those for aflatoxins, aflatrem, aflavarins, aflavinines, asparasones, cyclopiazonic acid, kojic acid, leporins and penicillin (Chang et al., 2009, Geogianna et al., 2010, Marui et al., 2010, Terebayashi et al., 2010, Chang and Ehrlich, 2011, Marui et al., 2011, Amare and Keller, 2014, Ehrlich and Mack, 2014, Tang et al., 2015, Cary et al., 2015a, Cary et al., 2015b, Cary et al., 2017, Gilbert et al., 2016, Ammar et al., 2017, Chang et al., 2017, Ibarra et al., 2018). Genome sequencing of more strains in section Flavi will help elucidating how the gene clusters for aflatoxins and ochratoxins evolved. Sexual reproduction appears to be important for the variation between isolates of A. flavus, so acquisition of new alleles and mitochondrial inheritance are factors that should be taken into consideration (Horn et al. 2016).

For food safety purposes, correct species identification is of high importance (Kim et al., 2014, Samson et al., 2006, Probst et al., 2007, Probst et al., 2010, Probst et al., 2012, Probst et al., 2014, Varga et al., 2011), as different species may have different mycotoxin profiles and physiology. For example, A. flavus strains used to prevent aflatoxin production in crops, themselves unable to produce aflatoxins, may produce other potentially toxic secondary metabolites (Ehrlich, 2014). Detection of these species in foods using sophisticated analytical techniques requires an accurate and reliable taxonomic system (Frisvad et al., 2007, Godet and Munaut, 2010, Luo et al., 2014a, Luo et al., 2014b, Faustinelli et al., 2017, Kaya-Celiker et al., 2015). Occasionally, strains producing important mycotoxins are apparently misidentified. An example of a dubious link between fungal species and mycotoxins is the production of the A. fumigatus metabolites fumigaclavine A (Jahardhanan et al. 1984) and fumitremorgins (Ma et al. 2016) by an A. tamarii strain. There is evidence that aflatoxigenic species can hybridize (Olarte et al., 2012, Olarte et al., 2015), so it should be examined whether some of the species producing aflatoxins may be hybrids. Furthermore, cells of A. flavus are multinucleate (Runa et al. 2015), and it is unknown whether such nuclei contain the same genetic material.

In this manuscript we present an update on the taxonomy of section Flavi and describe eight new species using a polyphasic approach combining physiology, morphology, sequence and extrolite data. A list of accepted species (and their synonyms) belonging to section Flavi is presented. The ability of the new species to produce aflatoxin and ochratoxin A is studied and an overview on the mycotoxin producing potential of all section Flavi species is presented.

Materials and methods

Isolation of microfungi

A part of the strains used in the study was recently isolated during various surveys in different countries (Czech Republic, Nigeria, Iran). Soil and drillosphere (soil in immediate proximity of earthworm burrows) samples and samples from Allolobophora hrabei casts and intestines were collected in 2011–2013, always in spring and autumn, in the period of earthworm activity. Soil and drillosphere samples were collected by soil corer from the top 5 cm soil layer and A. hrabei casts were collected from the soil surface. Microscopic fungi were isolated by a dilution plate method (dilution 104) and a soil washing technique (Garrett, 1981, Kreisel and Schauer, 1987) using three isolation media: dichloran rose bengal chloramphenicol agar (DRBC), Sabouraud's glucose agar (SGA) and beer wort agar (BWA). Rose bengal and chloramphenicol were added to the two latter media to suppress bacterial growth (Atlas 2010). Isolation from the A. hrabei intestine was done according to Nováková & Pižl (2003). Agar media were incubated for 7 days at 25 °C in darkness. For cultures from Nigeria, food (local rice, maize, mushroom, peanut cake and sesame) samples from various markets and agricultural soil samples from the top 2 cm of the soil were collected between October 2010 and February 2012. Cultures from food samples, except those from local rice and maize, were reported in other studies (Ezekiel et al., 2013a, Ezekiel et al., 2013b, Ezekiel et al., 2014). The isolates were previously reported as unnamed taxon SBG based on phenotype (macro- and microscopic characters on 5/2 agar (5 % V-8 juice and 2 % agar, pH 5.2)) and aflatoxin production (on neutral red desiccated coconut agar) or A. parvisclerotigenus based on ITS, β-tubulin and calmodulin gene sequences. Local rice and maize grains were milled while soil was sieved prior to isolation of moulds on modified Rose Bengal Agar (mRBA; Cotty 1994) by dilution plating (Samson et al. 1995). Cultures on mRBA and 5/2 agar were incubated for 3 and 5 days, respectively, at 31 °C in darkness. Isolated colonies were purified on 5/2 agar. For cultures from Iran, soil samples were collected at 10–15 cm depth from Aspear Island in Urmia Lake, during 2011 and 2012. Isolations were carried out using the soil dilution plate on three culture media: malt extract agar (MEA), glucose peptone yeast extract agar (GPY) and potato dextrose agar (PDA) supplemented with various NaCl concentrations (0 to 3 %) (Arzanlou et al. 2016).

Strains

The recently isolated strains (see previous paragraph) were supplemented with strains from the 1) CBS culture collection, housed at the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, 2) CCF, Culture Collection of Fungi, Prague, Czech Republic, 3) DTO, the working collection of the Applied and Industrial Mycology department housed at the Westerdijk Institute, 4) IBT, the culture collection of at the Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, 5) KACC, Korean Agricultural Culture Collection, Wanju, South Korea. Interesting strains and strains representing new species were deposited into the public CBS culture collection.

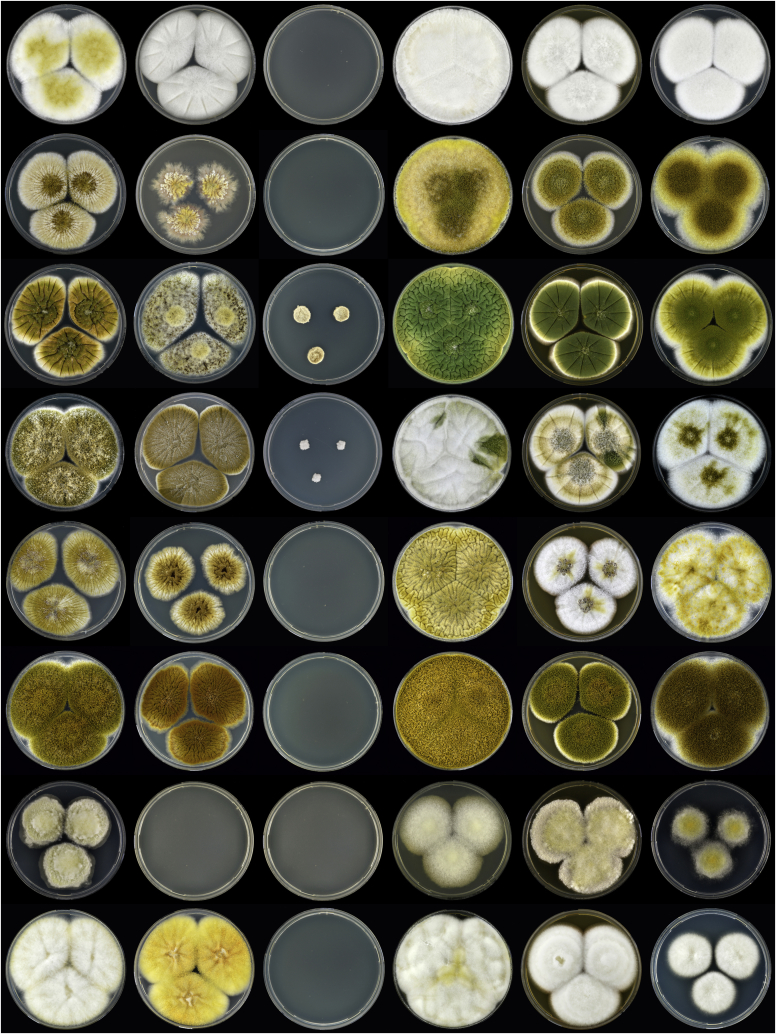

Morphological characterisation

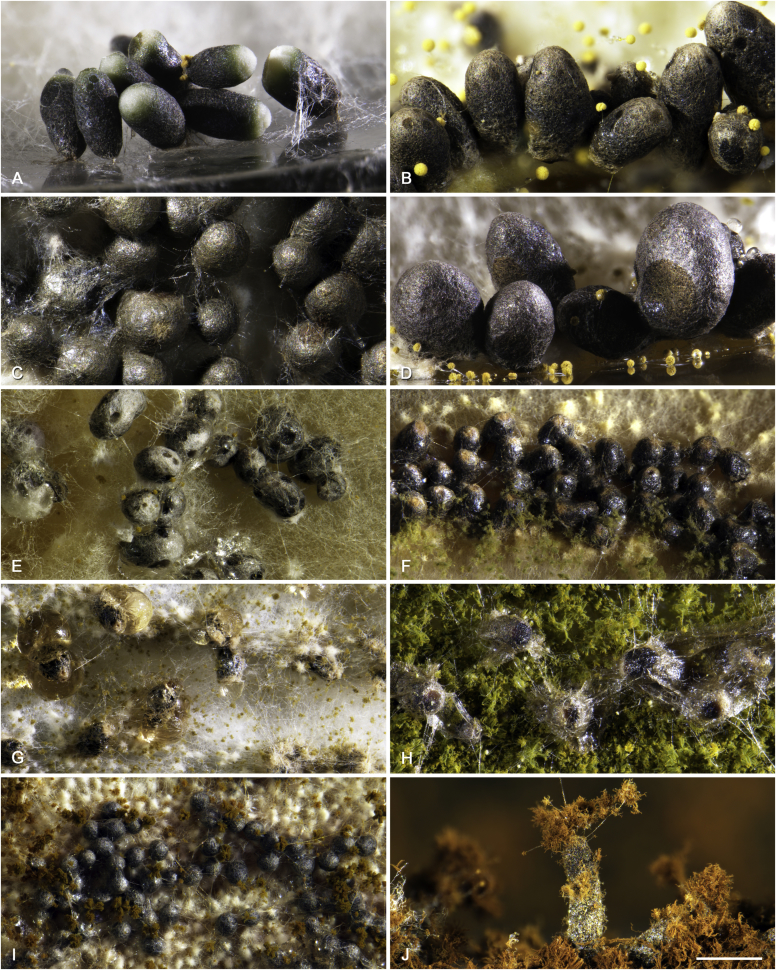

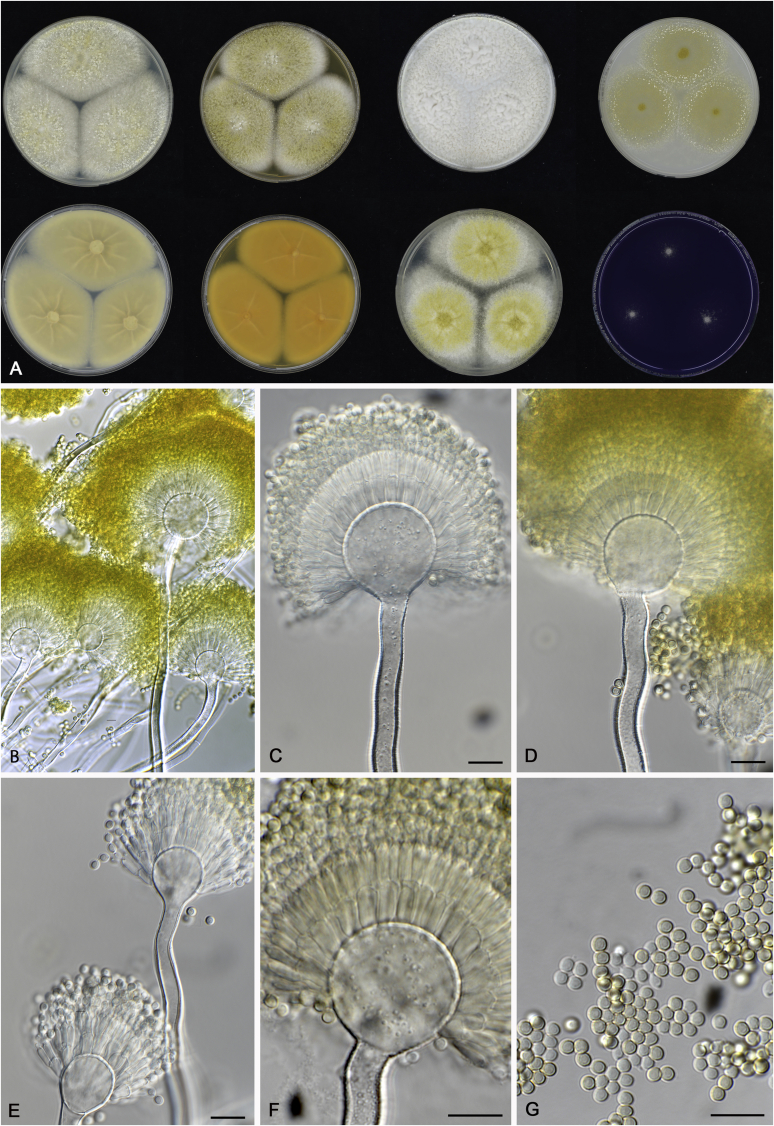

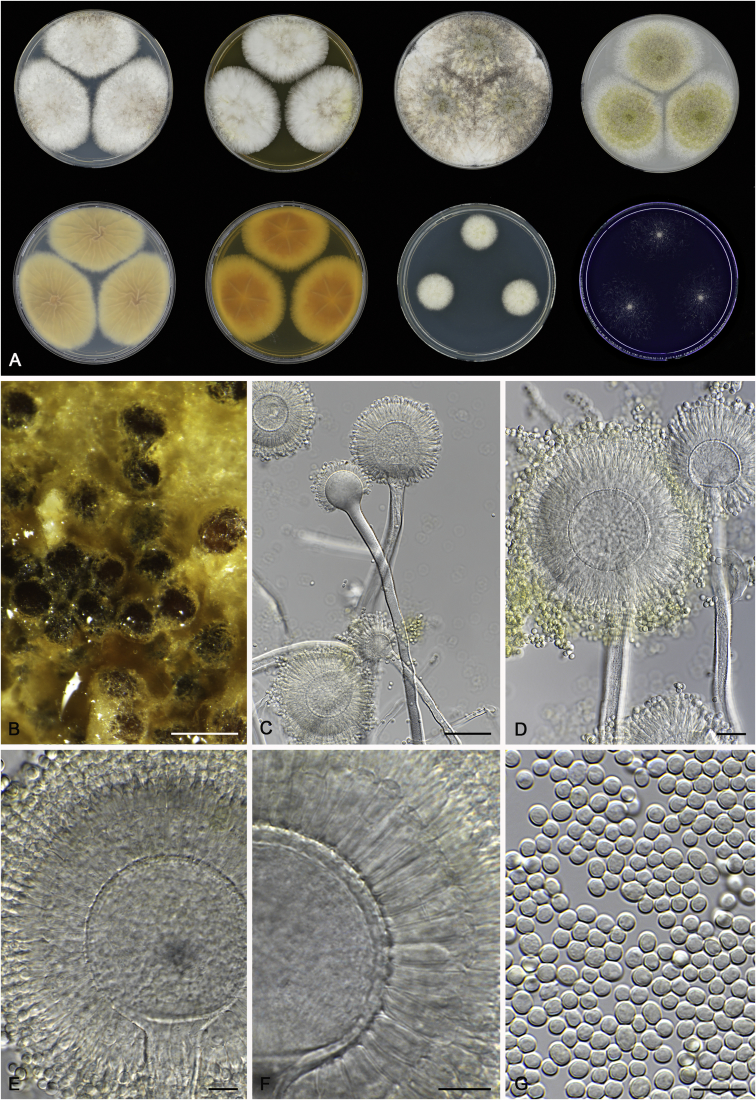

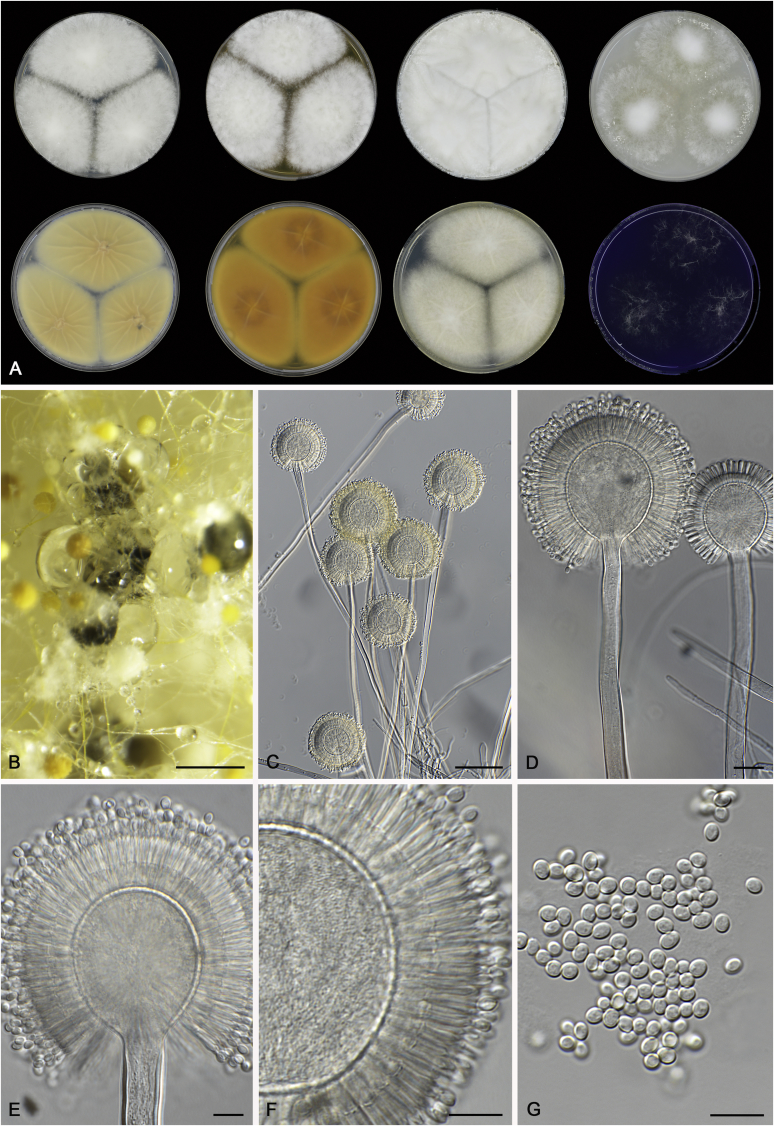

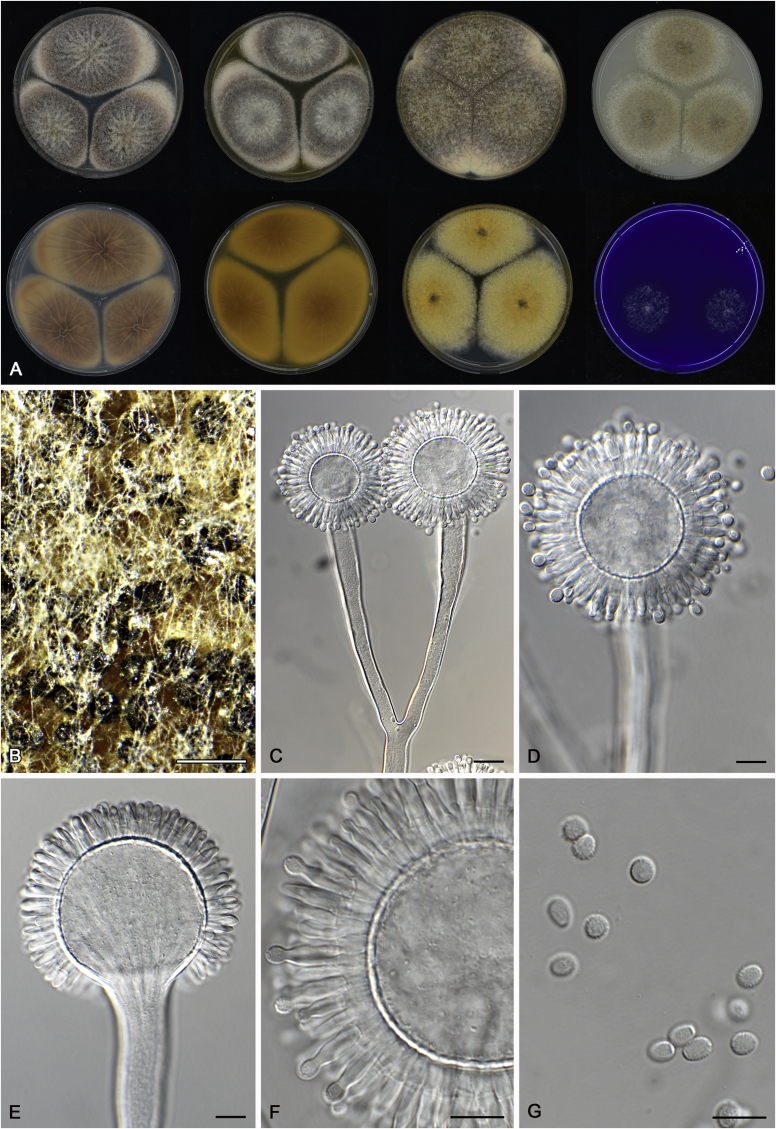

Cultures for macromorphological observations were inoculated in a three point position onto the agar media creatine sucrose agar (CREA), Czapek yeast extract agar (CYA), CYA supplemented with 5 % NaCl (CYAS), dichloran 18 % glycerol agar (DG18), malt extract agar (Oxoid) (MEA), oatmeal agar (OA) and yeast extract sucrose agar (YES). All media were prepared as described by Samson et al. (2014). Additional CYA plates were inoculated and incubated at 37 °C (CYA37°C) and 42 °C (CYA42°C). Colony texture, degree of sporulation, obverse and reverse colony colours, production of soluble pigments, exudates and sclerotia/ascomata were determined and recorded after 7 d of incubation. Colours names and codes used in descriptions refer to Rayner (1970). The production of sclerotia was observed with the naked eye. Digital images of these structures were made from CYA plates (incubate at 25 or 37 °C) and captured using a Nikon SMZ25 dissecting microscope. For micromorphological observations, mounts were made in lactic acid (60 %) from colonies on MEA and a drop of ethanol was used to wash excess conidia. The possible production of a sexual state was observed on OA, MEA and CYA plates incubated up to six weeks. Structures were studied and captured by using a Zeiss AX10 Imager A2 light microscope equipped with a Nikon DS-Ri2 camera and the software package NIS-Elements D v4.50. Photoplates were prepared in Adobe® Photoshop® CS6.

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

DNA was extracted from 3–7 days-old colonies with the DNA extraction kit ArchivePure DNA yeast and Gram2+ kit (5PRIME Inc., Gaithersburg, Maryland) with modifications described by Hubka et al. (2015) or the UtracleanTM Microbial DNA isolation kit (MoBio, Solana Beach U.S.A.). The ITS rDNA region was amplified using forward primers ITS1 and ITS5 (White et al. 1990) and reverse primers ITS4S (Kretzer et al. 1996 or NL4 (O’Donnell 1993), or the primer pair V9G (de Hoog & Gerrits van den Ende, 1998) and LS266 (Masclaux et al. 1995); a part of the BenA gene encoding β-tubulin using the forward primers Bt2a (Glass & Donaldson 1995) or Ben2f (Hubka & Kolařík 2012) and the reverse primer Bt2b (Glass & Donaldson 1995); partial CaM gene encoding calmodulin using forward primers CF1M or CF1L and reverse primer CF4 (Peterson 2008), or the primer pair cmd5 and cmd6 (Hong et al. 2005); partial RPB2 gene using forward primers fRPB2-5F (Liu et al. 1999), RPB2-F50-CanAre (Jurjević et al. 2015), RPB2-5F_Eur (Houbraken et al. 2012) and reverse primers RPB2-7CR_Eur (Houbraken et al. 2012) and fRPB2-7cR (Liu et al. 1999). PCR protocols were described by Hubka et al., 2014, Hubka et al., 2016 and Samson et al. (2014). Automated sequencing was performed with the same primers as used in PCR reactions.

Phylogenetic analysis

The sequence data were inspected, assembled and optimised using the software package Seqman (v. 10.0.1) from DNAStar Inc. Sequences were aligned with MAFFT v.7 (Katoh & Standley 2013) using the L-INS-i method. Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis on the combined data sets was performed using the RAxML v. 7.2.6 (randomized axalerated maximum likelihood) software (Stamatakis & Alachiotis 2010). The combined data sets were analysed as three distinct partitions (BenA, CaM and RPB2). For each individual data set, the most optimal substitution model was calculated in the MEGA7 v. 7.0.25 software (Kumar et al. 2016) utilising the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Maximum Likelihood analysis of the individual data sets was analysed performed using MEGA7 and the robustness of the trees was evaluated by 1 000 bootstrap replicates. A second measure for statistical support was performed using MrBayes v. 3.2.2 (Ronquist et al. 2012) and the previously obtained most optimal substitution model was used in the analyses. The Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis used four chains and started from a random tree topology. Burn-in was set to 25 % and Tracer v. 1.5.0 (Rambaut & Drummond 2009) was used to confirm the convergence of chains. The phylograms obtained during the ML analysis were used for presenting the data. Phylograms were redrawn from the tree files using TREEVIEW (Page 1996) and optimized using Adobe® Illustrator® CS5.1. Bootstrap (BS) values lower than 70 % and posterior probability (pp) values lower than 0.95 were removed from the phylograms. The phylogenetic relationship of species belonging to section Flavi is studied using a combined data set of partial BenA, CaM and RPB2 gene sequences. The relationship of strains (and species) belonging to five clades (A. alliaceus-, A. flavus-, A. leporis-, A. nomius- and A. tamarii-clade) is studied in more detail. The reason of these detail analyses is that either these clades contain new species and/or we found that the taxonomy of those clades was not well re-solved. Aspergillus muricatus NRRL 35674T was used as out-group in the overview of section Flavi, Aspergillus tamarii NRRL 20818 in the A. flavus- and A. leporis-clade phylogenies and A. bertholletius CBS 143687T in the A. alliaceus-, A. nomius- and A. tamarii-clade phylogenies.

Extrolite analysis

Strains were grown for 7 d at 25 °C on YES and CYA prior to extrolite extraction. The strains of the recently described species were inoculated on Czapek yeast autolysate (CYA) agar, malt extract agar (MEA) (Blakeslee formula), MEA-Ox (Oxoid formula), yeast extract sucrose (YES) agar, oat meal (OAT) agar, potato dextrose agar (PDA) (Difco), Wickerhams antibiotic test medium (WATM) and Raulin Thom oat meal (RTO) agar (Nielsen et al., 2011a, Nielsen et al., 2011b, Frisvad, 2012), and Aspergillus flavus parasiticus agar (AFPA) (Pitt et al. 1983).

Strains listed in Table 1 were tested for production of small molecule extrolites according to the agar plug extraction method of Filtenborg et al. (1983) as modified by Smedsgaard (1997). The HPLC-DAD method was following Frisvad & Thrane (1987), as modified by Nielsen & Smedsgaard (2003) and Nielsen et al., 2011a, Nielsen et al., 2011b. After extracting the agar plugs with ethylacetate /dichloromethane / methanol (3:2:1, vol/vol/vol) containing 1 % formic acid, the solvent was evaporated and the mixture of extrolites were re-dissolved in methanol, filtered and 1 μl was injected into a Agilent high performance liquid chromatograph with a diode array detector. Samples made after 2015 were extracted with ethylacetate / isopropanol (3:1, vol/vol), with 1 % formic acid. Selected strains were analyzed by Ultra high performance liquid chromatography-diode array detection-high resolution quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (UHPLC-DAD-HRQTOFMS) according to the method of Kildgaard et al. (2014) and Klitgaard et al. (2014) using an Agilent Infinity 1290 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) as described in detail by Kildgaard et al. (2014).

Table 1.

Isolates examined belonging to Aspergillus section Flavi.

| Species | Isolate number | Provenance | GenBank accession no. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | BenA | CaM | RPB2 | |||

| Aspergillus aflatoxiformans | CBS 143679 = DTO 228-G2T = IBT 32085 | Agricultural soil, Minna, Niger State, Nigeria, ex type of Aspergillus aflatoxiformans | MG662388 | MG517706 | MG518076 | MG517897 |

| CBS 121.62 = IMI 093070 = NRRL A-11612 = IBT 3651 = IBT 3850 = DTO 010-H7 = DTO 223-C2 = DTO 228-H6 | Arachis hypogea, Nigeria, PKC Austwick, 1962 (former suggested neotype of Aspergillus parvisclerotigenus) | EF409240 | MG517719 | MG518089 | MG517910 | |

| CBS 133264 = DTO 215-F3 | Edible mushroom, Lagos State, Nigeria | – | JX627690 | JX627694 | MG517871 | |

| CBS 133265 = DTO 215-F4 | Edible mushroom, Lagos State, Nigeria | – | JX627691 | JX627695 | MG517872 | |

| CBS 133923 = DTO 215-F1 | Peanut cake, Niger State, Minna, Nigeria | – | MG517680 | MG518051 | MG517869 | |

| CBS 133924 = DTO 215-F2 | Peanut cake, Niger State, Minna, Nigeria | – | MG517681 | MG518052 | MG517870 | |

| CBS 133925 = DTO 215-F5 | Peanut cake, Kaduna, Nigeria | – | MG517682 | MG518053 | MG517873 | |

| DTO 087-A2 | Soil near road, Ifaty, Madagascar | MG662405 | MG517652 | MG517990 | MG517840 | |

| DTO 228-G1 = IBT 32079 | Stored rice grains from market, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria | MG662389 | MG517705 | MG518075 | MG517896 | |

| DTO 228-G3 = IBT 32086 = CBS 135587 | Sesame kernels from market, Plateau State, Vwrang, Nigeria | MG662387 | MG517707 | MG518077 | MG517898 | |

| DTO 228-G4 = IBT 32087 = CBS 135588 | Sesame kernels from market, Plateau State, Vwrang, Nigeria | – | MG517708 | MG518078 | MG517899 | |

| DTO 228-G5 = IBT 32088 = CBS 135589 | Sesame kernels from market, Plateau State, B/Ladi, Nigeria | – | MG517709 | MG518079 | MG517900 | |

| DTO 228-G6 = IBT 32089 = CBS 135404 | Sesame kernels from market, Plateau State, B/Ladi, Nigeria | – | MG517710 | MG518080 | MG517901 | |

| DTO 228-G7 = IBT 32090 = CBS 135405 | Sesame kernels from market, Plateau State, B/Ladi, Nigeria | – | MG517711 | MG518081 | MG517902 | |

| DTO 228-H2 = IBT 16807 | Mexican sesame seed imported to Denmark and sold in Lyngby, JC Frisvad, 1995 | – | MG517715 | MG518085 | MG517906 | |

| DTO 228-H3 = IBT 16808 | Mexican sesame seed imported to Denmark and sold in Lyngby, JC Frisvad, 1995 | – | MG517716 | MG518086 | MG517907 | |

| DTO 228-H7 = IBT 32083 | Agricultural soil, Minna State, Nigeria | – | MG517720 | MG518090 | MG517911 | |

| Aspergillus alliaceus | CBS 536.65NT = DTO 046-B1 = NRRL 315 = IMI 051982 = QM 1885 = ATCC 10760 = WB 315 = Thom 4656 = IBT 13377 = CCF 5607 | Dead blister beetle (Microbasis albida), Washington D.C., USA, M.M. High, neotype of Aspergillus alliaceus | EF661551 | EF661465 | EF661534 | MG517825 |

| CBS 110.26 = DTO 034-B2 = DTO 046-A7 = IBT 14351 = NRRL 316 = WB 316 = IMI 016125 = Thom 4660 = CCF 5603 | Allium cepa | MH279383 | MG517632 | MG518004 | MG517815 | |

| CBS 143682 = DTO 326-D5 = S757 = CCF 5416 = IBT 33356 | Intestine of Allolobophora hrabei, National Reservation Pouzdřanská step - Kolby, Czech Republic, A. Nováková, 2013 | MH279421 | MG517764 | MG518134 | MG517955 | |

| CBS 511.69 = DTO 368-C3 = IBT 13379 = CCF 5682 | Soil, Turkey | MH279439 | MG517786 | MG518156 | MG517976 | |

| CBS 542.65 = DTO 034-A9 = DTO 203-B1 = NRRL 4181 = ATCC 16891 = IBT 13378 = IMI 116711 = QM 1892 = WB 4181 = JH Warcup SA 117 | Soil, Australia, ex type of Petromyces alliaceus | EF661556 | EF661466 | EF661536 | EU021644 | |

| DTO 363-E8 = NRRL 318 = IBT 21073 = CCF 5601 | Unknown source | MH279430 | MG517776 | MG518146 | MG517967 | |

| DTO 363-E9 = IBT 23440 = EXF-670 = CCF 5605 | Saltern, Secovlje, Slovenia, P. Zalar | MH279431 | MG517777 | MG518147 | MG517968 | |

| DTO 363-F1 = IBT 21992 = A196 = CCF 5604 | Mixed feed, Spain | MH279432 | MG517778 | MG518148 | MG517969 | |

| DTO 363-F2 = IBT 21754 = IMI 017295 = CCF 5606 | Contaminant in ex type culture of Aspergillus wentii | MH279433 | MG517779 | MG518149 | – | |

| DTO 368-C4 = IMI 226007 = IBT 14130 = CCF 5680 | Soil, Calicut University, India | MH279440 | MG517787 | MG518157 | MG517977 | |

| IBT 21770 | Prairie soil, Nebraska, USA | MH279446 | MG517790 | MG518161 | MG517980 | |

| Mo2 | Soil above the Movile cave, Romania, 2011, A. Nováková | MH279443 | MG517791 | LT558734 | MG517981 | |

| NRRL 1206 = Thom 5741 | Unknown source | EF661543 | EF661463 | EF661535 | EU021622 | |

| NRRL 20602 = ATCC 58745 = IBT 14317 = UAMH 2476 | Clinical isolate from human ear, Alberta, Canada, ex type of Aspergillus albertensis | EF661548 | EF661464 | EF661537 | EU021628 | |

| S862 = CCF 4954 | Soil above the Movile cave, Romania, A. Nováková, 2013 | MH279444 | MG517615 | MG518160 | MG517795 | |

| S916 = CCF 5434 | Allolobophora hrabei casts, National Monument Ječmeniště, Czech Republic, A. Nováková, 2013 | MH279442 | MG517616 | MG518159 | MG517796 | |

| S98 = CCF 4953 | Soil above Movile cave, Romania, A. Nováková, 2012 | MH279445 | MG517614 | LT558735 | MG517794 | |

| Aspergillus arachidicola | CBS 117610T = DTO 009-G3 = IBT 25020 | Arachis glabrata leaf, Mercedes, Corrientes province, Argentina, ex type of Aspergillus arachidicola | MF668184 | EF203158 | EF202049 | MG517802 |

| CBS 117611 = DTO 009-G4 = IBT 27185 | Arachis glabrata leaf, Mercedes, Corrientes province, Argentina | - | MG517620 | MG518006 | MG517803 | |

| CBS 117615 = DTO 010-H5 = IBT 28178 | Arachis glabrata leaf, Ituzaingó, Corrientes province, Argentina | – | MG517627 | MG517999 | MG517810 | |

| DTO 228-H9 | Leaf of Protea roupelliae var. roupelliae, Buffelskloof, South Africa | MG662384 | MG517721 | MG518091 | MG517912 | |

| Aspergillus aspearensis | CBS 143672T = DTO 203-D9 = CCTU758 = IBT 32590 = IBT 34544 | Soil, Aspear Island, Urmia Lake, Iran, soil, ex type of Aspergillus aspearensis | MG662398 | MG517669 | MG518040 | MG517857 |

| DTO 203-D4 = CBS 143671 = CCTU753 = IBT 34543 | Soil, Aspear Island, Urmia Lake, Iran | MG662399 | MG517667 | MG518038 | MG517855 | |

| DTO 203-E1 = CBS 143673 = CCTU759 = IBT 32591 | Soil, Aspear Island, Urmia Lake Iran | MH279394 | MG517670 | MG518041 | MG517858 | |

| Aspergillus austwickii | CBS 143677T = DTO 228-F7 = IBT 32590 = IBT 32076 | Stored rice grains from market, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria, ex type of Aspergillus austwickii | MG662391 | MG517702 | MG518072 | MG517893 |

| CBS 135406 = DTO 228-G8 = IBT 32091 | Sesame kernels from market, Plateau State, B/Ladi, Nigeria | MG662386 | MG517712 | MG518082 | MG517903 | |

| CBS 143678 = DTO 228-F8 = IBT 32077 | Stored rice grains from market, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria | – | MG517703 | MG518073 | MG517894 | |

| DTO 228-F9 = IBT 32078 | Stored rice grains from market, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria | MG662390 | MG517704 | MG518074 | MG517895 | |

| Aspergillus avenaceus | CBS 109.46T = DTO 009-H6 = DTO 006-A2 = NRRL 517 = ATCC 16861 = IMI 016140 = LCP 89.2592 = LSHB BB 155 = QM 6741 = WB 317 = IBT 4376 = IBT 4555 | Green pea (Pisum sativum), United Kingdom, G.E. Turfitt, 1938, ex type of Aspergillus avenaceus | AF104446 | FJ491481 | FJ491496 | JN121424 |

| CBS 102.45 = NCTC 6548 | Unknown source, United Kingdom | – | FJ491480 | FJ491495 | – | |

| Aspergillus bertholletius | CBS 143687 = DTO 223-D3 = IBT 29228 = CCT 7615T = ITAL 270/06 | Soil close to Bertholletia excelsa trees, Amazonian rainforest, Brazil, ex type of Aspergillus betholletius | JX198673 | MG517689 | JX198674 | MG517880 |

| IBT 29227 = ITAL 275/06 = CCT 7618 | Soil close to Bertholletia excelsa trees, Amazonian rainforest | – | – | – | – | |

| IBT 30617 = ITAL 272/06 = CCT 7617 | Soil close to Bertholletia excelsa trees, Amazonian rainforest | – | – | – | – | |

| DTO 223-D4 = IBT 30618 = ITAL 271/06 = CCT 7616 | Soil close to Bertholletia excelsa trees, Amazonian rainforest | – | – | – | – | |

| IBT 31739 = ITAL 262 = CCT 7614 | Bertholletia excelsa nut shell, Market, Amazon | – | – | – | – | |

| Aspergillus caelatus | CBS 763.97T = DTO 046-A8 = NRRL 25528 = IBT 21091 | Soil, USA, ex type of Aspergillus caelatus | AF004930 | MG517640 | MG518018 | MG517823 |

| CBS 764.97 = NRRL 25404 | Soil, USA | – | EF203129 | EF202036 | - | |

| DTO 276-I2 | Corn silage, Cordoba, Argentina | – | MG517738 | MG518108 | MG517929 | |

| DTO 285-H9 | Soil from corn field, Thailand | – | MG517751 | MG518121 | MG517942 | |

| DTO 285-I1 | Soil from corn field, Thailand | – | MG517752 | MG518122 | MG517943 | |

| NRRL 25566 = IBT 29770 = DTO 073-B7 | Soil, Japan | – | MG517651 | MG518025 | MG517839 | |

| NRRL 25567 = IBT 29773 = DTO 073-B8 | Soil, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| NRRL 25568 = IBT 29772 = DTO 073-B9 | Soil, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| NRRL 25569 = IBT 29771 = DTO 073-C1 | Soil, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| NRRL 26100 | Soil of peanut field, 2.5 km east of Herod, Georgia, USA | EF661550 | EF661471 | EF661523 | EF661437 | |

| Aspergillus cerealis | CBS 143674T = DTO 228-E7 = IBT 32067 | Stored rice grains from market, Shagamu, Ogun State, Nigeria, ex type of Aspergillus cerealis | MG662394 | MG517693 | MG518063 | MG517884 |

| CBS 143675 = DTO 228-E8 = IBT 32068 | Stored rice grains from market, Shagamu, Ogun State, Nigeria | – | MG517694 | MG518064 | MG517885 | |

| CBS 143676 = DTO 228-E9 = IBT 32069 | Stored maize grains from market, Shagamu, Ogun State, Nigeria | MG662393 | MG517695 | MG518065 | MG517886 | |

| DTO 228-E6 = IBT 32076 | Stored rice grains from market, Shagamu, Ogun State, Nigeria | MG662395 | MG517692 | MG518062 | MG517883 | |

| DTO 228-F1 = IBT 32070 | Stored maize grains from market, Shagamu, Ogun State, Nigeria | MG662392 | MG517696 | MG518066 | MG517887 | |

| DTO 228-F2 = IBT 32071 | Stored maize grains from market, Shagamu, Ogun State, Nigeria | – | MG517697 | MG518067 | MG517888 | |

| DTO 228-F3 = IBT 32072 | Stored maize grains from market, Shagamu, Ogun State, Nigeria | – | MG517698 | MG518068 | MG517889 | |

| DTO 228-F4 = IBT 32073 | Stored maize grains from market, Shagamu, Ogun State, Nigeria | – | MG517699 | MG518069 | MG517890 | |

| DTO 228-F5 = IBT 32074 | Stored maize grains from market, Shagamu, Ogun State, Nigeria | – | MG517700 | MG518070 | MG517891 | |

| DTO 228-F6 = IBT 32075 | Stored maize grains from market, Shagamu, Ogun State, Nigeria | – | MG517701 | MG518071 | MG517892 | |

| MACI219 = NRRL 66709 | Peanut pods, Pokaha, Karhogo region, North part of Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) | KY689208 | KY628791 | KY661266 | – | |

| MACI254 = NRRL 66710 | Peanut pods, Gbandokaha, Karhogo region, North part of Côte d’Ivoire, 2014, probably ex type of Aspergillus korhogoensis | KY689209 | KY628792 | KY661267 | – | |

| MACI264 = NRRL 66711 | Peanut pods, Gbandokaha, Karhogo region, North part of Côte d’Ivoire, 2014 | KY689210 | KY628793 | KY661268 | – | |

| MACI46 = NRRL 66708 | Peanut pods, Karhogo region, North part of Côte d’Ivoire, 2014 | KY689207 | KY628790 | KY661265 | – | |

| Aspergillus coremiiformis | CBS 553.77T = DTO 046-A3 = ATCC 38576 = IHEM 4503 = IMI 223069 = NRRL 13603 = NRRL 13756 = IBT 3822 = IBT 13506 = IBT 21944 | Soil, Tai National Forest, Ivory Coast, ex type of Aspergillus coremiiformis | AJ874114 | FJ491482 | FJ491488 | JN121533 |

| Aspergillus flavus | CBS 100927T = NRRL 1957 = ATCC 16883 = CBS 569.65 = IMI 124930 = IBT 3605 = IBT 3610 | Cellophane diaphragm of an optical mask, South Pacific Islands, ex type of Aspergillus flavus | AF027863 | EF661485 | EF661508 | EF661440 |

| AF70 | Seed of upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), Arizona, USA, genome sequenced | – | genome* | genome* | genome* | |

| CBS 110.55 = DTO 046-A1 = ATCC 12073 = NRRL 4743 = IMUR 236 = QM 6951 = WB 4743 = IBT 3819 | Air contaminant, Brazil, ex type of Aspergillus fasciculatus | FJ491463 | EF203135 | MG518005 | MG517821 | |

| CBS 117637 = DTO 009-F9 = IBT 27177 | Arachis hypogea seed, Provincia de Formosa, Las Lomitas, Argentina | – | MG517618 | MG518010 | MG517800 | |

| CBS 117638 = DTO 009-G1 | Arachis hypogea seed, Provincia de Corrientes, Empedrado, Argentina | – | MG517619 | MG518011 | MG517801 | |

| CBS 117732 = NRRL 3251 = IBT 3597 = IBT 3618 | Walnut, USA (small sclerotia) | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 118.62 = DTO 010-H6 = IFO 7600 = IMI 091548 = NRRL A-11608 = RIB 1406 | Arachis hypogea, Brazil | – | MG517628 | MG517996 | MG517811 | |

| CBS 119368 = DTO 011-I2 = KACC 41730 | Wheat, Boun-up, Boukun, Chungbuk Prov., South Korea | – | MG517630 | MG518002 | MG517813 | |

| CBS 120.51 = DTO 046-A4 = ATCC 16859 = IFO 8135 = IMI 045644 = LCP 56.1517 = LSHB BB213 = NRRL 2097 = NRRL A-2022 = QM 6871 = WB 2097 = IBT 3636 | Culture contaminant, London, England, ex type of Aspergillus thomii | EF661549 | MG517639 | MG518012 | MG517822 | |

| CBS 128202 = NRRL 3357 = ATCC 200026 = IBT 3696 = IBT 28518 = IBT 29624 | Peanut cotyledons, USA, genome sequenced | JX535495 | genome* | genome* | genome* | |

| CBS 133263 = DTO 215-E9 | Edible mushroom from market, Lagos State, Nigeria | – | JX627689 | JX627693 | MG517868 | |

| CBS 143688 = DTO 359-D8 = KACC 46894 = IBT 34547 | Air, South Korea | – | MG517774 | MG518144 | MG517965 | |

| CBS 143689 = DTO 359-D9 = KACC 46895 = IBT 34548 | Air, South Korea | – | MG517775 | MG518145 | MG517966 | |

| CBS 485.65 = DTO 046-B7 = ATCC 16870 = IFO 5324 = IMI 124932 = LCP 89.3556 = NRRL 4818 = WB 4818 = IBT 3641 = IBT 3657 | Butter, Japan, ex type of Aspergillus flavus var. columnaris and A. flavus var. asper | EF661563 | MG517643 | MG518014 | MG517828 | |

| CBS 501.65 = DTO 046-B5 = ATCC 16862 = IMI 044882 = NRRL 4998 = WB 4998 = IBT 4378 = IBT 4402 | Cotton lintafelt, England, ex neotype of Aspergillus subolivaceus | EF661563 | MG517642 | MG518015 | MG517827 | |

| CBS 542.69 = DTO 046-B4 = IMI 141553 = NRRL 3751 = GKC 1421(1) = IBT 3649 | Stratigraphic core sample, soil, Niigata Pref., Kambara, Japan, ex type of Aspergillus kambarensis | EF661554 | MG517641 | MG518016 | MG517826 | |

| CBS 574.65 = DTO 303-C3 = ATCC 1010 = IMI 016142 = IMI 124935 = NRRL 506 = NRRL 1653 | Corn (Zea mays), Vermont, USA, representative of A. effusus fideThom & Church (1926) and Thom & Raper (1945) (Raper & Fennell 1965:377) | JN185448 | JN185446 | JN185447 | JN185449 | |

| DTO 016-I5 = dH 16719 | Infection of leg (after liver transplantation), male 43 year old, China | – | MG517631 | MG518003 | MG517814 | |

| DTO 062-C7 | Peanut, Indonesia | – | MG517645 | MG517985 | MG517832 | |

| DTO 062-C8 | Peanut, Indonesia | – | MG517646 | MG517986 | MG517833 | |

| DTO 062-H7 | Peanut, Indonesia | – | MG517647 | MG517987 | MG517834 | |

| DTO 066-C3 | Corn kernels, Indonesia | – | MG517650 | MG517989 | MG517837 | |

| DTO 087-A3 | Forest soil, Ifaty, Madagascar | – | MG517653 | MG517991 | MG517841 | |

| DTO 087-A4 | Forest soil, Ifaty, Madagascar | – | MG517654 | MG517992 | MG517842 | |

| DTO 215-E5 | Laboratory contaminant, Nigeria | – | MG517679 | MG518050 | MG517867 | |

| DTO 258-C9 | Corn kernels, from East.Europe, imported to the Netherlands | – | MG517725 | MG518095 | MG517916 | |

| DTO 258-D6 | Corn kernels, from East.Europe, imported to the Netherlands | – | MG517728 | MG518098 | MG517919 | |

| DTO 276-H7 | Poultry feedstuff, Cordoba, Argentina | – | MG517734 | MG518104 | MG517925 | |

| DTO 276-H8 | Poultry feedstuff, Cordoba, Argentina | – | MG517735 | MG518105 | MG517926 | |

| DTO 276-H9 | Poultry feedstuff, Cordoba, Argentina | – | MG517736 | MG518106 | MG517927 | |

| DTO 276-I1 | Poultry feedstuff, Cordoba, Argentina | – | MG517737 | MG518107 | MG517928 | |

| DTO 276-I3 | Corn silage, Cordoba, Argentina | – | MG517739 | MG518109 | MG517930 | |

| DTO 276-I4 | Chinchilla feedstuffs, Cordoba, Argentina | – | MG517740 | MG518110 | MG517931 | |

| DTO 276-I5 | Chinchilla feedstuffs, Cordoba, Argentina | – | MG517741 | MG518111 | MG517932 | |

| DTO 276-I6 | Chinchilla feedstuffs, Cordoba, Argentina | – | MG517742 | MG518112 | MG517933 | |

| DTO 276-I7 | Chinchilla feedstuffs, Cordoba, Argentina | – | MG517743 | MG518113 | MG517934 | |

| DTO 276-I8 | Chinchilla feedstuffs, Cordoba, Argentina | – | MG517744 | MG518114 | MG517935 | |

| DTO 281-E2 | Rice, Thailand | – | MG517745 | MG518115 | MG517936 | |

| DTO 281-H8 | Rice, Thailand | – | MG517746 | MG518116 | MG517937 | |

| DTO 285-F6 | Soil from corn-field, Thailand | – | MG517748 | MG518118 | MG517939 | |

| DTO 285-G3 | Soil from corn-field, Thailand | – | MG517749 | MG518119 | MG517940 | |

| DTO 285-I4 | Soil from corn-field, Thailand | – | MG517753 | MG518123 | MG517944 | |

| DTO 300-C7 | Corn kernels, imported into the Netherlands | – | MG517754 | MG518124 | MG517945 | |

| DTO 300-D7 | Corn kernels, imported into the Netherlands | – | MG517755 | MG518125 | MG517946 | |

| DTO 359-D7 = IBT 34546 = KACC 46893 | Air, South Korea | – | – | – | – | |

| DTO 359-E1 = IBT 34551 = KACC 46897 | Corn, South Korea | – | – | – | – | |

| DTO 359-E2 = IBT 34550 = KACC 46913 | Soil, South Korea | – | – | – | – | |

| DTO 359-E3 = KACC 46917 | Soil, Gyoenggi, Suwon, Korea | |||||

| NRRL 20521 | Corn, Mississippi, USA | EF661547 | EF661492 | EF661514 | EF661447 | |

| NRRL 3518 = NRRL A-14304 | Wheat flour, Peoria, Illinois, USA | EF661552 | EF661487 | EF661510 | EF661442 | |

| NRRL 4822 | Unknown source | EF661564 | EF661490 | EF661513 | EF661445 | |

| Aspergillus hancockii | FRR 3425T = CBS 142004 = DTO 360-G7 | Cultivated soil, Queensland, Australia, ex type of Aspergillus hancockii | KX858342 | MBFL01001228.1:26000-28000 | MBFL01000377.1:5000-7000 | MBFL01000137:9000-11000 |

| CBS 142001 = FRR 5050 = DTO 360-G4 = IBT 35030 | Soil, Lockhart, New South Wales, Australia, J.I. Pitt, 2003 | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 142002 = FRR 6103 = DTO 360-G5 = IBT 35031 | Dried peas, Victoria, Australia, M. Bull, 1997 | – | – | – | – | |

| Aspergillus lanosus | CBS 650.74T = IMI 130727 = QM 9183 = IBT 33634 | Soil under Tectona grandis, Uttar Pradesh, India | FJ491471 | MG517633 | MG518017 | EU021642 |

| Aspergillus leporis | CBS 151.66T = IBT 3609 = DTO 199-B2 = CBS 129302 = RMF 99 = WB 5188 = ATCC 16490 = LCP 89.2583 = NRRL 3216 | Dung of Lepus townsensii, near Saratoga, Wyoming, USA, ex type of Aspergillus leporis | MH279391 | MG517662 | MG518033 | MG517850 |

| CBS 125914 = DTO 195-C3 = R1251 | A1 horizon soil, open area in sagebrush grassland, Rock Springs, Wyoming, USA (DOE site, 11 km west of Rock Springs) | MH279389 | MG517660 | MG518031 | MG517848 | |

| CBS 129235 = DTO 303-C5 | Plant root tissue at non-seleniferous soil, Nunn, Colorado, USA | – | MG517760 | MG518130 | MG517951 | |

| CBS 129310 = RMF 9587 = DTO 201-H1 | A1 horizon soil, Canyonlands National Park, Utah, USA | MH279392 | MG517663 | MG518034 | MG517851 | |

| CBS 129330 = RMF 7757 = DTO 202-A2 | Soil beneath Atriplex confertifolia, near Jim Bridger Power Plant, Sweetwater County, Wyoming, USA | MH279393 | MG517664 | MG518035 | MG517852 | |

| CBS 129596 = DTO 206-A8 = RMF G74 | A1 horizon soil from bunchgrass rhizosphere, sagebrush grassland, Rock Springs, Wyoming, USA | MH279395 | MG517673 | MG518044 | MG517861 | |

| CBS 132153 = DTO 210-E1 | Surface soil, near Dubois, Wyoming, USA | MH279396 | MG517674 | MG518045 | MG517862 | |

| CBS 132177 = RMF 2050 = DTO 210-G5 | A1 Horizon soil, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, USA | MH279397 | MG517676 | MG518047 | MG517864 | |

| CBS 349.81 = IBT 3600 = NRRL 6599 = DTO 303-C4 = ATCC 44565 = Strain O168 | Soil, Wyoming, USA | EF661569 | EF661500 | EF661542 | EF661460 | |

| IBT 12296 = IBT 13578 = ATCC 76617 | Soil undre grass, Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, USA | – | – | – | – | |

| IBT 16309 = RMF A39 | Soil under Atriplex gardneri, cool desert, 10 km north of Rock Springs, Great Divide Basin, Wyoming, USA | – | – | – | – | |

| IBT 16585 | Soil under Atriplex confertifolia, cool desert, 10 km north of Rock Springs, Great Divide Basin, Wyoming, USA | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 132178 = RMF 2110 = DTO 210-G6 | A1 Horizon soil, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, USA | MH279398 | MG517677 | MG518048 | MG517865 | |

| Aspergillus luteovirescens | CBS 620.95T = DTO 010-H1 | Unknown source, ex type of Aspergillus luteovirescens | MG662406 | MG517625 | MG517998 | MG517808 |

| CBS 117187 = NRRL 25010 = IBT 23536 | Frass in a sílkworm rearing house, Japan, 1987, ex type of Aspergillus bombycis | AF104444 | EF661498 | EF661533 | EF661458 | |

| DTO 073-C3 = NRRL 29236 = IBT 29777 | Frass in a silkworm rearing house, 1983, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| DTO 073-C4 = NRRL 29237 = IBT 29780 | Frass in a silkworm rearing house, 1983, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| DTO 073-C5 = NRRL 29241 = IBT 29779 | Frass in a silkworm rearing house, 1983, Oita Prefecture, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| ITAL 246 = IBT 31534 | Brazil nut, Amazon, Brazil | – | – | – | – | |

| NRRL 25593 = IBT 23535 | Frass in a sílkworm rearing house, Japan, 1987 | AF104445 | EF661497 | EF661532 | EF661457 | |

| NRRL 29235 = DTO 073-C2 = IBT 23537 = IBT 29778 | Frass in a silkworn rearing house, Indonesia, 1999 | AF338641 | AY017575 | AY017622 | – | |

| Aspergillus minisclerotigenes | CBS 117635T = DTO 009-F7 = IBT 25032 | Arachis hypogea, Manfredi, Córdoba province, Argentina, ex type of Aspergillus minisclerotigenes | EF409239 | EF203148 | MG518009 | MG517799 |

| CBS 117633 = DTO 009-F5 | Arachis hypogea seed, Provincia de Formosa, Las Lomitas, Argentina | MG662408 | EF203153 | MG518007 | MG517797 | |

| CBS 117634 = DTO 009-F6 = IBT 27197 | Arachis hypogea seed, Provincia de Cordoba, Alejandro, Argentina | MG662402 | MG517617 | MG518008 | MG517798 | |

| DTO 045-F4 = FRR 4086 | Freshly pulled peanuts, Interlaw Road, Kingaropy, Queensland, Australia | – | MG517635 | MG518021 | MG517817 | |

| DTO 045-F5 = FRR 4937 | Soil, Australia | – | MG517636 | MG518022 | MG517818 | |

| DTO 045-F6 = FRR 5309 | Soil, Coalston Lakes, Queensland, Australia | – | MG517637 | MG518023 | MG517819 | |

| DTO 045-I9 = NRRL A-11611 = NRRL 6444 = IBT 3840 | Soil of peanut field, Nigeria | MH279386 | MG517638 | MG518024 | MG517820 | |

| DTO 228-G9 = IBT 32094 | Agricultural soil, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria | – | MG517713 | MG518083 | MG517904 | |

| DTO 228-H1 = IBT 32111 | Agricultural soil, Minna, Niger State, Nigeria | – | MG517714 | MG518084 | MG517905 | |

| DTO 228-H5 = IBT 24629 | Curry powder from Kenya imported to Denmark | – | MG517718 | MG518088 | MG517909 | |

| Aspergillus mottae | CBS 130016T = DTO 223-C8 = IBT 32309 = MUM 10.231 | Maize kernel, Braga, Portugal, ex type of Aspergillus mottae | JF412767 | MG517687 | MG518058 | MG517878 |

| MUM 10.233 | Maize, Portugal | – | HM803090 | HM803013 | HM802982 | |

| Aspergillus neoalliaceus | CBS 143681T = DTO 326-D3 = S765 = CCF 5433 = IBT 33110 = IBT 33353 | Soil, Czech Republic, National Reservation Pouzdřanská step - Kolby, A. Nováková, 2013, ex type of Aspergillus neoalliaceus | MH279420 | MG517763 | MG518133 | MG517954 |

| CBS 134375 = S77 = CCF 4424 | Soil, National Monument Ječmeniště, Czech Republic, A. Nováková, 2012 | MH279441 | MG517613 | MG518158 | MG517793 | |

| DTO 326-D6 = S768 = CCF 5414 = IBT 33111 = IBT 33357 | Drilosphere soil, National Reservation Pouzdřanská step – Kolby, Czech Republic, A. Nováková, 2013 | MH279422 | MG517765 | MG518135 | MG517956 | |

| DTO 326-D7 = B6 = CCF 5408 = IBT 32726 | Soil, National Reservation Pouzdřanská step – Kolby, Czech Republic, A. Nováková, 2010 | MH279423 | MG517766 | MG518136 | MG517957 | |

| DTO 326-E1 = S756 = CCF 5410 = IBT 33359 | Soil, National monument Ječmeniště, Czech Republic, A. Nováková, 2013 | MH279424 | MG517768 | MG518138 | MG517959 | |

| DTO 326-E2 = S766 = CCF 5412 = IBT 33355 | Allolobophora hrabei cast, National Reservation Pouzdřanská step – Kolby, Czech Republic, A. Nováková, 2013 | MH279425 | MG517769 | MG518139 | MG517960 | |

| DTO 326-E4 = S764 = CCF 5411 = IBT 33358 | Soil, National monument Ječmeniště, Czech Republic, A. Nováková, 2013 | MH279426 | MG517770 | MG518140 | MG517961 | |

| DTO 326-E5 = S913 = CCF 5415 = IBT 33351 | Soil, National monument Ječmeniště, Czech Republic, A. Nováková, 2013 | MH279427 | MG517771 | MG518141 | MG517962 | |

| DTO 326-E7 = S767 = CCF 5413 = IBT 33109 = IBT 33352 | Soil, National Reservation Pouzdřanská step – Kolby, Czech Republic, A. Nováková, 2013 | MH279428 | MG517772 | MG518142 | MG517963 | |

| CCF 5815 = S1429 | Soil, above the Liliecilor de la Gura Dobrogei cave, Dobrogea, Romania, A. Nováková, 2016 | – | – | – | – | |

| CCF 5840 = S988 | Soil, above the Limanu cave, Dobrogea, Romania, A. Nováková, 2014 | – | – | – | – | |

| Aspergillus nomius | CBS 260.88T = NRRL 13137 = IBT 3656 = IBT4966 = FDA M93 | Wheat, USA, A.F. Schindler, 1965, ex type of Aspergillus nomius | AF027860 | EF661494 | EF661531 | EF661456 |

| CBS 117629 = NRRL 25585 = IBT 23530 | Silk worm frass, Japan, 1987 | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 399.93 = DTO 301-I8 = AS 3.4626 = IBT 14647 | Soil, Guandong, Zhaoqing, China, ex type of Aspergillus zhaoqingensis | FJ491472 | MG517757 | MG518127 | MG517948 | |

| DTO 161-F1 | Bamboo sample, Walailak, Thailand | MH279387 | MG517656 | MG518026 | MG517844 | |

| DTO 161-F2 | Bamboo sample, Addis Abeba, Ethiopia | MH279388 | MG517657 | MG518027 | MG517845 | |

| DTO 226-I5 | Storage room of cassava, Yogyakarta, Indonesia | – | MG517690 | MG518060 | MG517881 | |

| DTO 227-B8 | Storage room of cassava, Yogyakarta, Indonesia | – | MG517691 | MG518061 | MG517882 | |

| DTO 243-E8 | HIV-Care room, Indonesia | – | MG517722 | MG518092 | MG517913 | |

| DTO 247-F9 | House dust, Mexico | – | MG517723 | MG518093 | MG517914 | |

| DTO 247-G8 | House dust, Mexico | – | MG517724 | MG518094 | MG517915 | |

| DTO 318-F4 | Heat treated pectin, Germany | – | MG517761 | MG518131 | MG517952 | |

| DTO 321-F2 | Cystic fibrosis patient material, the Netherlands | MH279419 | MG517762 | MG518132 | MG517953 | |

| IMI 190557 = NRRL 20745 = IBT 19368 | Dried Curcuma longa, Central Crops Reseaerch Institute, India | AF338612 | AY017543 | AY017590 | – | |

| NRRL 13138 = IBT 4493 = IBT 4495 = IBT 5054 | Sub-isolate from a mixed culture, U.L. Diener, 1967 | – | – | – | – | |

| NRRL 3161 = IBT 3661 = IBT 4975 | Cycas circinalis, Guam, USA, A.C. Keyl, 1965 | AF338642 | EF661493 | EF661530 | EF661453 | |

| Aspergillus novoparasiticus | CBS 126849T = DTO 223-C3 = DTO 223-C4 = FMR 10121 = LEMI 250 = IBT 32311 | Sputum of leukemic patient, Sao Paolo, Brazil, ex type of Aspergillus novoparasiticus | MG662397 | MG517684 | MG518055 | MG517875 |

| CBS 126850 = DTO 223-C5 = FMR 10158 = LEMI 149 IOP = IBT 32312 | Air sample, Sao Paulo, Brazil | MH279415 | MG517686 | MG518057 | MG517877 | |

| Aspergillus oryzae | CBS 102.07T = CBS 110.47 = CBS 100925 = ATCC 1011 = ATCC 12891 = ATCC 4814 = ATCC 7651 = ATCC 9102 = CECT 2094 = IFO 4075 = IFO 5375 = IMI 016266ii = IMI 016266 = IMI 044242 = LSHBA c.19 = NCTC 598 = NRRL 447 = NRRL 692 = QM 6735 = Thom 113 = WB 447 = IBT 21451 | Unknown source, ex type of Aspergillus oryzae | EF661560 | EF661483 | EF661506 | EF661438 |

| NRRL 458 = ATCC 10063 = ATCC 9376 = IMI 051983 | Unknown source | EF661562 | EF661484 | EF661507 | EF661439 | |

| RIB40 = ATCC 42149 = JCM 13832 = NRRL 5590 = IBT 28103 | Horsebean, Muruka soy saúce factory, Mimaki-mura, Kuse-gun, Kyoto, Japan, genome sequenced | – | genome* | genome* | genome* | |

| Strain 100-8 | Mutant of A. oryzae 3.042, which is used in soy sauce fermentation, China, genome sequenced | – | genome* | genome* | genome* | |

| Aspergillus parasiticus | CBS 100926T = NRRL 502 = ATCC 1018 = ATCC 6474 = ATCC 7865 = IMI 015957 = IMI 015957ii = IMI 015597iv = IMI 015957vi = IMI 015957vii = IMI 015957ix = NRRL 1731 = IBT 3607 | Sugar cane mealy bug (Pseudococcus calceolariae), Hawaii, USA, ex neotype of Aspergillus parasiticus | AF027862 | EF661481 | EF661516 | EF661449 |

| CBS 104.22 = DTO 009-H2 = IFO 5867 | Unknown source | – | MG517621 | MG517994 | MG517804 | |

| CBS 119.51 = DTO 009-H3 = IFO 5337 | Unknown substrate, Japan | – | MG517622 | MG518000 | MG517805 | |

| CBS 138.52 = DTO 009-H4 | Unknown substrate, Japan | – | MG517623 | MG517997 | MG517806 | |

| CBS 260.67 = DTO 046-C2 = ATCC 15517 = CCM F-550 = CECT 2680 = DSM 2038 = IFO 30179 = IHEM 4387 = IMI 120920 = IMI 229041 = MUCL 31311 | Unknown source, Japan, ex type of Aspergillus parasiticus var. globosus | MG662400 | EF203156 | MG518013 | MG517830 | |

| CBS 580.65 = DTO 046-B9 = ATCC 1014 = ATCC 16863 = IMI 016127ii = LSHB Ac22 = NCTC 974 = NRRL 424 = QM 7475 = VKM F-2041 = WB 424 = IBT 3664 = IBT 3670 = IBT 10828 | Soil, Georgia, USA, ex type of Aspergillus terricola var. americana | MG662404 | MG517644 | MG518030 | MG517829 | |

| CBS 822.72 = DTO 046-A9 = ATCC 22789 = IFO 30109 = IMI 089717 = RIB 4002 = TRI M 39 = IBT 4377 = IBT 4408 | Arachis hypogea, Uganda, ex type of Aspergillus toxicarius | MG662401 | EF203163 | MG518019 | MG517824 | |

| CBS 921.70 = ATCC 26691 = CECT 2681 = IHEM 4383 = NRRL 2999 = IBT 3634 = IBT 15675 | Unknown source, Uganda | AB008418 | – | – | – | |

| DTO 203-C4 | Soil, Aspear Island, Iran | – | MG517666 | MG518037 | MG517854 | |

| DTO 203-H7 | Soil, Kabodan Island, Iran | – | MG517672 | MG518043 | MG517860 | |

| DTO 258-D1 | Corn kernels from East-Europe imported to the Netherlands | – | MG517726 | MG518096 | MG517917 | |

| DTO 258-D4 | Corn kernels from East-Europe imported to the Netherlands | – | MG517727 | MG518097 | MG517918 | |

| DTO 283-C6 | Soil from corn.field, Thailand | – | MG517747 | MG518117 | MG517938 | |

| DTO 285-G9 | Soil from corn.field, Thailand | – | MG517750 | MG518120 | MG517941 | |

| DTO 301-E6 | Corn kernels, imported to the Netherlands | – | MG517756 | MG518126 | MG517947 | |

| DTO 303-C2 | Unknown source | – | MG517759 | MG518129 | MG517950 | |

| NRRL 13005 = IBT 4564 | Microarthropod in beech forest litter, Michigan, USA (produces sclerotia) | – | – | – | – | |

| NRRL 4123 | Toxic grain | EF661555 | EF661479 | EF661518 | EF661451 | |

| NRRL 6433 = IBT 4375 | Corn, North Carolina, USA | EF661568 | EF661480 | EF661519 | EF661452 | |

| Aspergillus pipericola | CBS 143680T = DTO 228-H4 = IBT 24628 | Black pepper, unknown origin, imported to Denmark, ex type of Aspergillus pipericola | MG662385 | MG517717 | MG518087 | MG517908 |

| Aspergillus pseudocaelatus | CBS 117616T = DTO 010-H4 = IBT 27191 | Arachis burkartii leaf, Mercedes, Corrientes province, Ituzaingó, Argentina | EF409242 | MG517626 | MG517995 | MG517809 |

| ITAL 103CC = IBT 29230 | Peanuts, Brazil | – | – | – | – | |

| ITAL 1300F/09 = IBT 30532 | Brazil nuts, Amazon, Brazil | – | – | – | – | |

| Aspergillus pseudonomius | CBS 119388T = DTO 009-F1 = NRRL 3353 = IBT 27864 = IBT 14897 | Diseased alkali bee (Nomius sp.), Wyoming, USA | AF338643 | EF661495 | EF661529 | EF661454 |

| DTO 177-G7 | Soil of corn-field, Phayao, Thailand | – | MG517659 | MG518029 | MG517847 | |

| DTO 262-F3 | Indoor environment of child hospital, Izmir, Turkey | – | MG517729 | MG518099 | MG517920 | |

| DTO 267-D6 | House dust, Micronesia | MH279416 | MG517731 | MG518101 | MG517922 | |

| DTO 267-H7 | House dust, Thailand | MH279417 | MG517732 | MG518102 | MG517923 | |

| DTO 267-I4 | House dust, Thailand | – | MG517733 | MG518103 | MG517924 | |

| IBT 12657 = DTO 303-A4 | Seed, unknown location | MH279418 | MG517758 | MG518128 | MG517949 | |

| ITAL 823/07 | Brazil nut, Amazon, Brazil | – | – | – | – | |

| ITAL 849F = IBT 32759 | Brazil nut, Amazonas, Brazil | – | – | – | – | |

| NRRL 6552 | Diseased pine sawfly, Wisconsin, USA, C.R. Benjamin, 1967 | – | EF661496 | EF661528 | EF661455 | |

| Aspergillus pseudotamarii | CBS 766.97T = NRRL 25517 = DTO 046-C1 = IBT 21092 | Soil, teafield, Japan | AF272574 | EF661477 | EF661521 | EU021631 |

| CBS 117625 = NRRL 25518 = IBT 21090 | Soil, teafield, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 117628 = NRRL 25519 = IBT 21093 | Soil, teafield, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 765.97 = NRRL 443 | Unknown source | AF004931 | EF661476 | EF661520 | EU021650 | |

| ITAL 791F/09 = IBT 30530 | Brazil nut, Amazonas, Brazil | – | – | – | – | |

| ITAL 792F/09 = IBT 30531 | Brazil nut, Amazonas, Brazil | – | – | – | – | |

| Aspergillus sergii | CBS 130017T = DTO 223-C9 = IBT 32292 = IBT 32293 | Fruits of Prunus dulcis, Trans-Os-Montes processing plant, Faro, Portugal, ex type of Aspergillus sergii | JF412769 | MG517688 | MG518059 | MG517879 |

| Aspergillus sojae | CBS 100928T = DTO 046-C3 = ATCC 42251 = IAM 2669 = IFO 4244 = IFO 30112 = IMI 191300 = RIB 1045 = SRRC 1126 = K. Sakaguchi SH-10-6 = IBT 21642 = IBT 32109 | Koji of soy sauce, shoyu brewing, 1942, ex neotype of Aspergillus sojae | KJ175434 | EF203168 | EF202041 | MG517831 |

| CBS 100929 = NISL 1909 = IBT 21643 | Soy sauce, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 100930 = NISL 1939 = IBT 21644 | Soy sauce, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 100931 = NISL 1905 = IBT 21645 | Soy sauce, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 100932 = IAM 2665 = IFO 4239 = NISL 1777 = IBT 21646 | Soy sauce, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 100933 = NISL 1939 = IBT 21647 | Soy sauce, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 100934 = IAM 2718 = IFO 4274 = RIB 1050 = NISL 1849 = IBT 21648 | Soy sauce, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 100935 = NISL 1920 = IBT 21649 | Soy sauce, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 100936 = IAM 2678 = RIB 1024 = IBT 21650 | Soy sauce, Japan (produces versicolorins) | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 126.59 = IFO 5241 = IMI 191304 = Ohashi 1124 = IBT 3669 = IBT 3682 | Miso brewing, Okayama Agricultural Experiment Station, Japan | – | – | – | – | |

| CBS 133.52 = ATCC 9362 = CECT 2095 = IMI 087159 = NRRL 1947 = NRRL 1988 = NRRL 4841 = WB 4841 = IBT 3595 | Soy sauce, unknown origin | EF661546 | EF661482 | EF661517 | EF661450 | |

| DTO 173-C3 = IFM 46699 | Unknown source | – | MG517658 | MG518028 | MG517846 | |

| NRRL 5594 = IBT 4600 | Unknown source | – | – | – | – | |

| Aspergillus subflavus | CBS 143683T = DTO 326-E8 = S778 = CCF 4957 = NRRL 66254 = IBT 34939 | Soil, near Movile Cave, Romania, A. Nováková, 2013, ex type of Aspergillus subflavus | MH279429 | MG517773 | MG518143 | MG517964 |

| S843b | Moonmilk, Na Špičáku cave, Czech Republic, A. Nováková, 2013 | MH279449 | MG517792 | MG518164 | MG517983 | |

| Aspergillus tamarii | CBS 104.13T = NRRL 20818 = QM 9374 = IBT 3648 | Activated carbon, unknown origin, ex neotype of Aspergillus tamarii | AF004929 | EF661474 | EF661526 | EU021629 |

| CBS 133097 = DTO 213-H5 = NRRL 4959 | Unknown source, representative of Aspergillus tamarii var. crassus | MG662403 | MG517678 | MG518049 | MG517866 | |

| CBS 133393 = NRRL 4966 = IMI 016124 = IBT 3628 | Seed, cacao, unknown origin | EU021614 | EU021673 | EU021686 | EU021652 | |

| DTO 010-G9 = CBS 167.63 = NRRL 4680 = ATCC 15054 = IMI 172295 = QM 8903 = WB 4680 = IBT 22566 | Mouldy bread, India (ex type of Aspergillus indicus and A. terrricola var. indicus). Isolation of dihydrocanadensolide, fumaric acid, fumaryl-D,L-alanine, indazonic acid = cyclopiazonic acid, kojic acid, succinic acid and 3-nitropropionic acid show that these metabolites can be produced by A. tamarii (Birch et al., 1968) | MG662407 | MG517624 | MG518001 | MG517807 | |

| DTO 065-A4 | Indoor environment, Germany | MH279381 | MG517648 | MG517984 | MG517835 | |

| DTO 066-A1 | Corn kernels, Indonesia | - | MG517649 | MG517988 | MG517836 | |

| DTO 145-C3 | Indoor environment, Germany | MH279382 | MG517655 | MG517993 | MG517843 | |

| DTO 266-D7 | House dust, Mexico | - | MG517730 | MG518100 | MG517921 | |

| DTO 364-E3 | Air in chocolate factory, the Netherlands | MH279435 | MG517781 | MG518151 | MG517971 | |

| NRRL 425 | Unknown source, representative of Aspergillus lutescens nomen nudum | EF661558 | EF661475 | EF661524 | EU021648 | |

| NRRL 426 = DTO 010-H3 = CBS 579.65 = IBT 3681 = IBT 3826 = IBT 10827 | Unknown substrate, USA, ex neotype of Aspergillus terricola | EF661559 | EF661472 | EF661525 | EU021649 | |

| NRRL 4911 = CBS 484.65 = IBT 3659 | Air contaminant, Brazil, ex neotype of Aspergillus flavofurcatus | EF661565 | EF661473 | EF661527 | EU021651 | |

| Aspergillus togoensis | CBS 205.75T = LCP 67.3456 = NRRL 13551 = IBT 14899 = IBT 21943 | Decaying fruit of Landolphia sp., Central African Republic, ex type of Aspergillus togoensis | – | – | – | – |

| CBS 272.89 = DTO 034-C1 = NRRL 13550 = IBT 14989 = IBT 21943 | Seed, La Maboké, Central African Republic | AJ874113 | FJ491477 | FJ491489 | JN121479 | |

| Aspergillus transmontanensis | CBS 130015T = MUM 10.214 = IBT 32313 | Almond, Portugal, ex type of Aspergillus transmontanensis | JF412774 | HM803101 | HM803020 | HM802980 |

| MUM 10.205 | Almond, Portugal | JF412771 | HM803087 | HM803021 | HM802979 | |

| MUM 10.211 | Almond, Portugal | JF412772 | HM803102 | HM803023 | HM802968 | |

| MUM 10.221 | Almond, Portugal | JF446612 | HM803093 | HM803028 | HM802972 | |

| Aspergillus vandermerwei | CBS 612.78T = DTO 069-D2 = DTO 034-B5 = NRRL 5108 = IBT 13876 = CCF 5683 | Unknown source, Buenos Aires, Argentina, ex type of Aspergillus vandermerwei | EF661567 | EF661469 | EF661540 | MG517838 |

| DTO 199-A9 = CBS 129201 = DMSA 706 = IBT 16758 = CCF 5679 | Unknown source, USA, California | MH279390 | MG517661 | MG518032 | MG517849 | |

| DTO 210-F8 = CBS 132171 = IBT 16423 = RMF 7709 | Native shortgrass prairie, soil (1 m deep), Pawnee National Grassland, Colorado, USA | – | MG517675 | MG518046 | MG517863 | |

| DTO 363-F3 = NRRL 1237 = IBT 21072 = CCF 5602 | Unknown source | MH279434 | MG517780 | MG518150 | MG517970 | |

| DTO 368-B9 = IBT 16661 = CCF 5684 | Soil under crested wheat grass, 2 km south of Pryor, Colorado, USA | MH279436 | MG517783 | MG518153 | MG517973 | |

| DTO 368-C1 = NRRL 1236 = IBT 13865 = CCF 5685 | Unknown source | MH279437 | MG517784 | MG518154 | MG517974 | |

| DTO 368-C2 = CBS 126709 = RMF 9585 = IBT 20468 = CCF 5681 | Grassland, A1 soil horizon soil, Canyonlands National park, Utah, USA | MH279438 | MG517785 | MG518155 | MG517975 | |

| IBT 16662 | Soil under Senecio sp. (Asteraceae), Pablo Alto, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, USA | MH279447 | MG517788 | MG518162 | MG517978 | |

| IBT 20491 | A1 soil horizon, Canyonlands National park, Utah, USA | MH279448 | MG517789 | MG518163 | MG517979 | |

Culture collections: ATCC; American Type Culture Collection, Mayland, USA, CBS, Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands, CCF: Culture Collection of Fungi, Prague, Czech republic, CCM: Czech Collection of Microorganisms, Brno, Czech Republic, CCTU: Culture Collection of Tabriz University, Iran, DSM: Deutsche Samlung von Mikroorganismen und Cell-kulturen, Braunschweig, Germany, DTO: The fungal working collection at Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands, IAM : Center for Cellular and Molecular Research, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan (collection transferred to JCM), IFO (= NRBC) Institute of Fermentation, Osaka, Japan, IMI, CABI Fungal collection, Egham, UK, ITAL: Instituto de Technologia Alimentos, Campinas, Brazil, LCP: Laboratoire de Cryptogamie, Paris, France, KACC: Korean Agricultural Culture Collection, Seoul, South Korea, MUM: Micoteca da Univerdade do Minho, Portugal, NRRL, Northern Regional Research Lab, NCAUR, Peoria, Illinois, USA, QM: Quartermaster Collection, now at NRRL, Peoria, Illinois, USA, RIB: National Research Institute of Brewing, Higashihiroshima, Hiroshima, Japan, RMF: Rocky Mountain Fungi, collected by Martha Christensen, and situated in Laramie, Wyoming, USA, Thom: The original collection of Charles Thom, now at NRRL, WB: Wisconsin Bacteriology collection, Madison, Wisconsin, cultures now deposited at CBS, ATCC, IMI and IBT.

Results

Phylogenetic analysis

Various analyses were performed to study the phylogenetic relationship between species in section Flavi. Details on the number of included isolates, the length of the data sets and information on the used substitution model for each dataset are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Details of the length and substitution model of each data set.

| Description data set | No. isolates | BenA, length alignment | BenA, substitution model | CaM, length alignment | CaM, substitution model | RPB2, length alignment | RPB2, substitution model | Combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overview | 38 | 574 | K2 + G | 617 | TN93 + G | 880 | TN93 + G + I | 2071 |

| A. alliaceus-clade | 41 | 431 | K2 | 485 | TN93 + G | 760 | K2 + G | 1676 |

| A. flavus-clade | 133–138 | 481 | K2 | 529 | TN93 + G | 843 | TN93 + G | 1853 |

| A. leporis-clade | 16 | 510 | K2 + G | 555 | TN93 + G | 968 | TN93 + G | 2033 |

| A. nomius-clade | 25 | 504 | K2 + G | 528 | TN93 + G | 923 | TN93 | 1955 |

| A. tamarii-clade | 23 | 502 | K2 + G | 539 | HKY | 920 | K2 + G | 1961 |

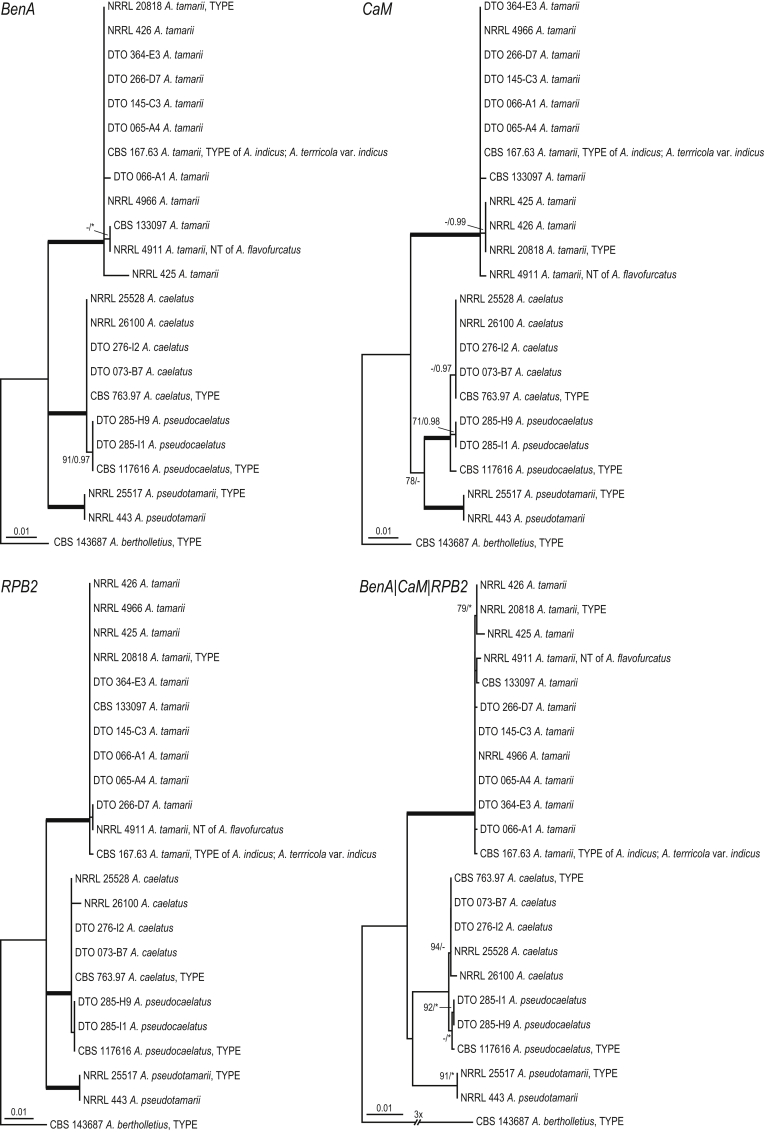

A phylogenetic study based on a combined data sets of loci (BenA, CaM, RPB2) was conducted to determine the relationship among Aspergillus section Flavi members. Aspergillus section Flavi could be subdivided into distinct eight clades: the A. alliaceus-, A. avenaceus-, A. bertholletius-, A. coremiiformis-, A. flavus-, A. leporis-, A. nomius- and A. tamarii-clade (Fig. 1). The A. flavus-clade is phylogenetically most closely related A. tamarii-clade and these clades form, together with the A. nomius- and the A. bertholletius-clades, a fully supported lineage. The phylogenetic relationship of the A. bertholletius-clade with the other clades remains partly unresolved in our analysis. In the ML analysis, the three A. bertholletius strains are placed with moderate statistical support (BS 83 %) in a basal position to the A. tamarii- and A. flavus-clades; however, no support was found in the Bayesian analysis (< 0.95 pp). The A. alliaceus- and A. coremiiformis-clades are also phylogenetically related (92 % BS, 1.00 pp) and these clades form a sister lineage to the A. flavus-, A. tamarii-, A. bertholletius- and A. nomius-clades. Aspergillus leporis and related species (A. leporis-clade) take a basal position to aforementioned clades and the A. avenaceus-clade, only represented by A. avenaceus, is basal in section Flavi.

Fig. 1.

Phylogeny inferred from a concatenated nucleotide data set (partial BenA, CaM and RPB2 sequences) using ML analysis showing the relationship of species accommodated in Aspergillus section Flavi. The bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The BI posterior probabilities values and bootstrap percentages of the ML analysis are presented at the node (BS/pp). Values less than 70 % bootstrap support in the ML analysis and less than 0.95 posterior probability in the Bayesian analysis are indicated with a hyphen. Branches with high support (> 95 % bs; 1.00 pp) are thickened and the BS and pp values indicated with an asterisks.

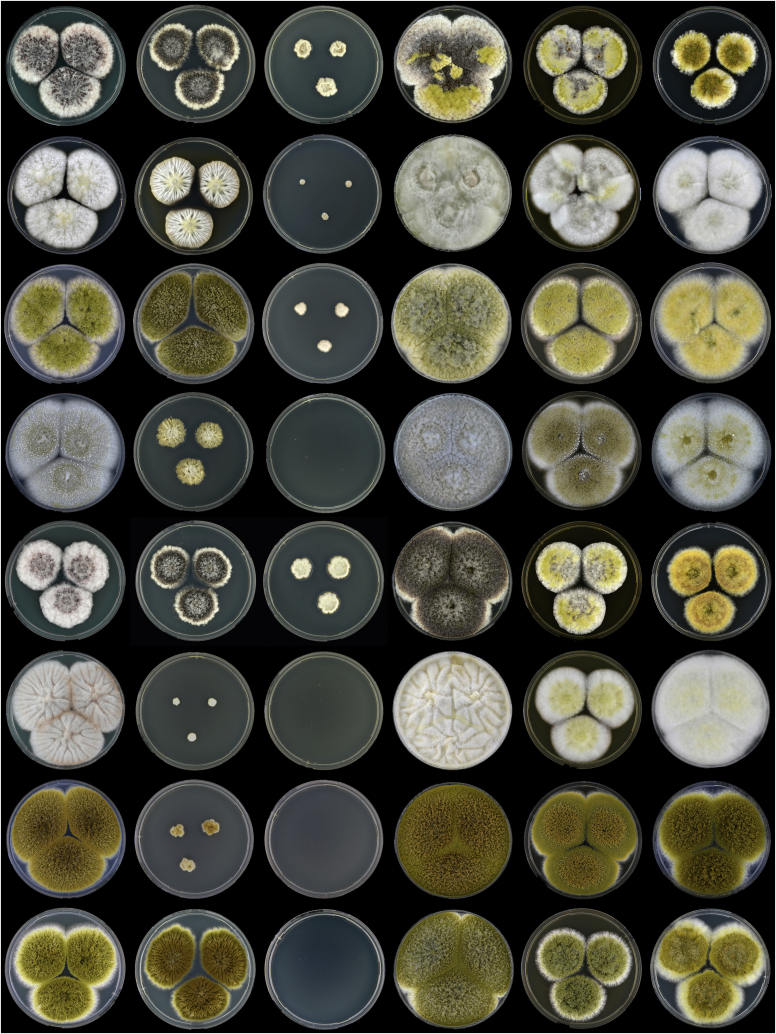

The A. flavus-clade is the most species-rich clade of section Flavi and contains 15 species (Fig. 2, Fig. 3), including the five new species described in this manuscript (see Taxonomy; A. aflatoxiformans, A. austwickii, A. cerealis, A. pipericola, A. subflavus). Analysis of the combined data set reveals four well-supported lineages in the A. flavus-clade. One main lineage is centered on A. flavus and contains A. aflatoxiformans, A. austwickii, A. cerealis, A. flavus, A. minisclerotigenes, A. oryzae and A. pipericola and the other main lineage (centered on A. parasiticus) includes A. arachidicola, A. novoparasiticus, A. parasiticus, A. sergii, A. sojae and A. transmontanensis. Aspergillus mottae has a basal position to the A. flavus and A. parasiticus lineages and A. subflavus is basal to all A. flavus-clade species. Almost all species could be resolved in the phylogenetic analysis of the combined data set. There are two exceptions: A. oryzae resides in a clade with A. flavus and A. sojae forms a clade with A. parasiticus. With the exception of A. flavus/A. oryzae and A. parasiticus/A. sojae, almost all species could be recognised using BenA, CaM or RPB2 sequences only. The exception is A. novoparasiticus and this species shares BenA sequences with A. parasiticus isolates. Strains CBS 485.65 (ex-type of A. flavus var. columnaris and A. flavus var. asper), CBS 501.65 (A. subolivaceus), CBS 542.69 (A. kambarensis), CBS 120.51 (A. thomii) and CBS 110.55 (A. fasciculatus) belong to the A. flavus/A. oryzae clade and CBS 260.67 (A. parasiticus var. globosus), CBS 580.645 (A. terricola var. americana) and CBS 822.72 (A. toxicarius) reside in the A. parasiticus/A. sojae clade. Two interesting A. flavus strains (from air, Korea) that produce aflatoxins of the B and G type (CBS 143688, CBS 143689) cluster in all analyses with other A. flavus/A. oryzae strains. Also two strains with small sized sclerotia (DTO 281-H8; NRRL 3251) belong to the A. flavus/A. oryzae lineage.

Fig. 2.

ML Phylogeny showing the relationship of species accommodated in the A. flavus-clade (left, BenA; right, CaM). The bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The BI posterior probabilities values and bootstrap percentages of the ML analysis are presented at the node (BS/pp). Values less than 70 % bootstrap support in the ML analysis and less than 0.95 posterior probability in the Bayesian analysis are indicated with a hyphen. Branches with high support (> 95 % bs; 1.00 pp) are thickened and the BS and pp values indicated with an asterisks.

Fig. 3.

Phylogeny showing the relationship of species accommodated in the A. flavus-clade (left, RPB2; right, combined data set of BenA, CaM and RPB2). The bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The BI posterior probabilities values and bootstrap percentages of the ML analysis are presented at the node (BS/pp). Values less than 70 % bootstrap support in the ML analysis and less than 0.95 posterior probability in the Bayesian analysis are indicated with a hyphen. Branches with high support (> 95 % bs; 1.00 pp) are thickened and the BS and pp values indicated with an asterisks.

Phylogenetic analysis reveals the presence of four species (A. caelatus, A. pseudocaelatus, A. pseudotamarii and A. tamarii) in the A. tamarii-clade (Fig. 4). The genetic distance between A. caelatus (CBS 763.97, DTO 073-B7, DTO 276-I2, NRRL 25528, NRRL 26100) and A. pseudocaelatus (DTO 285-H9, DTO 285-I1, CBS 117616) strains is low. In the phylogeny based on the combined data set, these strains resolve in two distinct clades. This clade is fully supported in the Bayesian analysis (1.00 pp); however, it lacks confident bootstrap support in the ML analysis (< 70 %). Representative strains of A. flavofurcatus (NRRL 4911), A. indicus and A. terricola var. indicus (CBS 167.63) cluster together with the type of A. tamarii (NRRL 20818) in all analyses.

Fig. 4.

Phylogeny showing the relationship of species accommodated in the A. tamarii-clade. The bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The BI posterior probabilities values and bootstrap percentages of the ML analysis are presented at the node (BS/pp). Values less than 70 % bootstrap support in the ML analysis and less than 0.95 posterior probability in the Bayesian analysis are indicated with a hyphen. Branches with high support (> 95 % bs; 1.00 pp) are thickened and the BS and pp values indicated with an asterisks.

Three species are accommodated in the A. nomius-clade: A. luteovirescens, A. nomius and A. pseudonomius (Fig. 5). Three well-supported, distinct clades could be recognised in the BenA analysis, representing the species accommodated in this clade. Not all species were resolved in the CaM and RPB2 analysis. The statistical support in the CaM phylogram was low. Aspergillus nomius strain DTO 321-F2 clustered with the included A. pseudonomius strains; however, statistical support was lacking. Phylogenetic analysis of the RPB2 data set could not resolve A. nomius and A. pseudonomius and strains of those species appear intermixed on one well-supported branch. The ex-type of A. zhaoqingensis (CBS 399.93) clusters together with the A. nomius strains in three out of the four analyses (BenA, CaM and combined analysis), and the ex-type of A. bombycis NRRL 26010T clusters with A. luteovirescens strains (incl. CBS 620.95NT).

Fig. 5.

Phylogeny showing the relationship of species accommodated in the A. nomius-clade. The bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The BI posterior probabilities values and bootstrap percentages of the ML analysis are presented at the node (BS/pp). Values less than 70 % bootstrap support in the ML analysis and less than 0.95 posterior probability in the Bayesian analysis are indicated with a hyphen. Branches with high support (> 95 % bs; 1.00 pp) are thickened and the BS and pp values indicated with an asterisks.

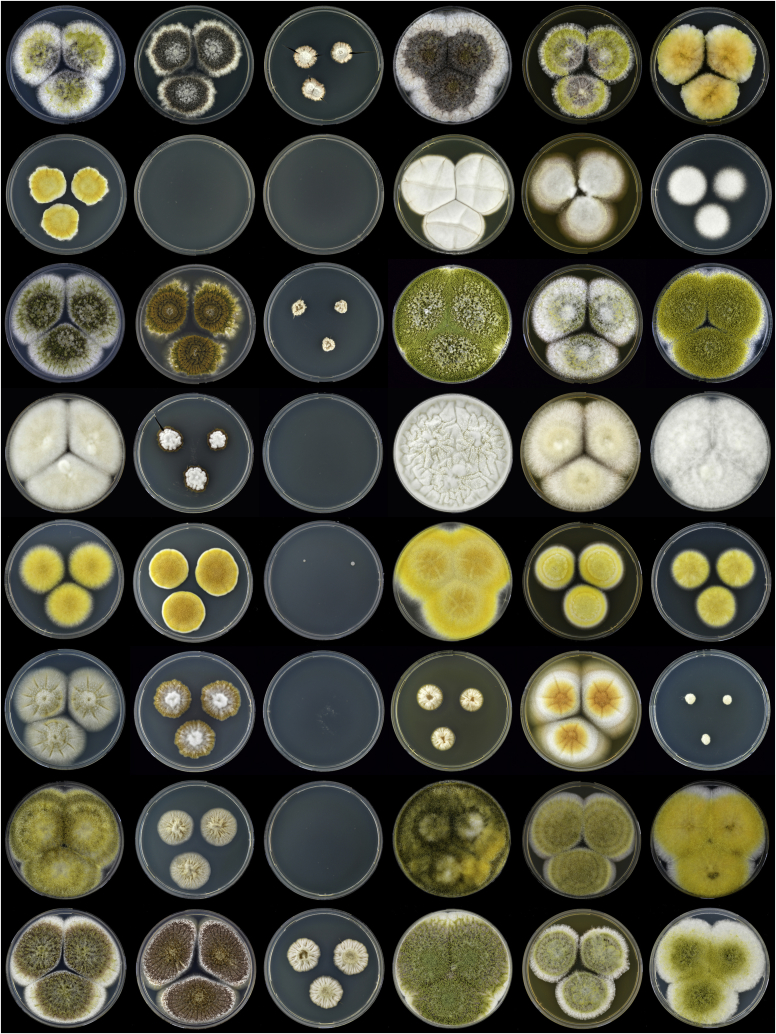

Four distinct groups in the A. alliaceus-clade can be recognised after assessment of the phylograms using the Genealogical Concordance Phylogenetic Species Recognition (GCPSR; Taylor et al. 2000) concept (Fig 6, Fig. 7). These groups represent two known (A. alliaceus, A. lanosus) and two new species (described here as A. neoalliaceus and A. vandermerwei). The deeper nodes in the phylograms often have a low statistical support and the relationship among species in the A. alliaceus-clade therefore remains unknown. A high BenA, CaM and RPB2 sequence diversity is present in the A. vandermerwei. Following the GCPSR concept, two groups can be recognised in A. vandermerwei: one includes CBS 129201, CBS 132171 and DTO 368-B9, and the other contains CBS 126709, DTO 368-C1, DTO 363-F3, IBT 20491, IBT 16662 and NRRL 5108T. The ex-type strain of A. albertensis, NRRL 20602, resides in the clade containing A. alliaceus isolates.

Fig 6.

ML Phylogeny showing the relationship of species accommodated in the A. alliaceus-clade (left, BenA; right, CaM). The bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The BI posterior probabilities values and bootstrap percentages of the ML analysis are presented at the node (BS/pp). Values less than 70 % bootstrap support in the ML analysis and less than 0.95 posterior probability in the Bayesian analysis are indicated with a hyphen. Branches with high support (> 95 % bs; 1.00 pp) are thickened and the BS and pp values indicated with an asterisks.

Fig. 7.

Phylogeny showing the relationship of species accommodated in the A. alliaceus-clade (left, RPB2; right, combined data set of BenA, CaM and RPB2). The bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The BI posterior probabilities values and bootstrap percentages of the ML analysis are presented at the node (BS/pp). Values less than 70 % bootstrap support in the ML analysis and less than 0.95 posterior probability in the Bayesian analysis are indicated with a hyphen. Branches with high support (> 95 % bs; 1.00 pp) are thickened and the BS and pp values indicated with an asterisks.

A set of strains isolated from soil of Aspear Island in Urmia Lake (Iran) formed a distinct lineage related to A. leporis and the name A. aspearensis is proposed for this group of isolates (Fig. 8). The third species in this clade is the recently described species A. hancockii (Pitt et al. 2017). All species can be recognised using the GCPSR concept.

Fig. 8.

Phylogeny showing the relationship of species accommodated in the A. leporis-clade. The bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. The BI posterior probabilities values and bootstrap percentages of the ML analysis are presented at the node (BS/pp). Values less than 70 % bootstrap support in the ML analysis and less than 0.95 posterior probability in the Bayesian analysis are indicated with a hyphen. Branches with high support (> 95 % bs; 1.00 pp) are thickened and the BS and pp values indicated with an asterisks.

Extrolite analysis

An overview of mycotoxins and other extrolites produced by Aspergillus section Flavi is given in Table 3, Table 4. The A. avenaceus- and A. leporis-clades are basal to the other clades in section Flavi (Fig. 1), but do not have the ability to produce aflatoxins or ochratoxins. Furthermore, A. avenaceus does not produce kojic acid, an extrolite produced by the majority of species in section Flavi (Table 3). Aflatoxins or precursors of aflatoxins are produced in all the other clades (the A. flavus-, A. tamarii-, A. bertholletius-, A. nomius-, A. alliaceus- and A. coremiiformis clades). Ochratoxin A and B are only found in the A. alliaceus-clade. Among the species in Aspergillus section Flavi, two species produced aflatoxin B1 and B2 only: A. pseudotamarii and A. togoensis. Sixteen species produced aflatoxin B1, B2, G1 and G2: A. aflatoxiformans, A. arachidicola, A. austwickii, A. cerealis, A. luteovirescens, A. minisclerotigenes, A. mottae, A. nomius, A. novoparasiticus, A. parasiticus, A. pipericola, A. pseudocaelatus, A. pseudonomius, A. sergii, A. transmontanensis and some strains of A. flavus (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. S1). One strain of A. bertholletius produced the aflatoxin B1 precursor O-methylsterigmatocystin (Taniwaki et al. 2012, and this result was confirmed here). Seven strains of A. flavus sensu stricto from Korea were found to produce aflatoxins of the B and G type (Table 3). Most isolates of A. alliaceus, A. neoalliaceus and A. vandermerwei produced large amounts of ochratoxin A (Table 3; Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Fig. S2). One strain of A. sojae and two strains of A. alliaceus produced versicolorins (Table 3), precursors of the aflatoxins. Another important mycotoxin, tenuazonic acid, is produced by eight species (A. bertholletius, A. caelatus, A. luteovirescens, A. nomius, A. pseudocaelatus, A. pseudonomius, A. pseudotamarii and A. tamarii) (Supplementary Fig. S3). The related mycotoxin cyclopiazonic acid was produced by 14 species: A. aflatoxiformans, A. austwickii, A. bertholletius, A. cerealis, A. flavus, A. hancockii (only speradine F found in this species), A. minisclerotigenes, A. mottae, A. oryzae, A. pipericola, A. pseudocaelatus, A. pseudotamarii, A. sergii and A. tamarii (Table 4, Supplementary Fig. S4).

Table 3.

Mycotoxin and other extrolite production by Aspergillus section Flavi species.

| Species | Extrolites reported in literature | Extrolites detected in this study | Examined strains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus aflatoxiformans | – | Aflatoxin B1, B2, G1, G2, aflatrems, aflavarins, aflavinines, aspergillic acid, aspirochlorin, cyclopiazonic acid, kojic acid, paspaline, paspalinine, versicolorins, metabolite gfn (UV absorbtions 240 nm & 397 nm, RI 1148) | DTO 228-G1, DTO 228-G2T DTO 228-G3, DTO 228-G4 DTO 228-G5, DTO 228-G6, DTO 228-G7, DTO 228-H2, DTO 228-H3, DTO 228-H6, DTO 228-H7, CBS 133923, CBS 133924, CBS 133264, CBS 133265, CBS 133925, DTO 087-A2, CBS 121.62, DTO 010-H7 |