Abstract

Purpose

To assess whether childhood exposure to violent contexts is prospectively associated with risky adolescent health behavior and whether these associations are specific to different contexts of violence and different types of risky behavior.

Methods

Data come from 2,684 adolescents in the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, a population-based, birth cohort study of children born between 1998–2000 in 20 large American cities. Using logistic regression models, we evaluate whether exposure to 6 indicators of community violence and 7 indicators of family violence at ages 5 and 9 is associated with risky sexual behavior, substance use, and obesity risk behavior at age 15.

Results

Controlling for a range of adolescent, parent, and neighborhood covariates, each additional point on the community violence scale is associated with 8% higher odds of risky sexual behavior but not substance use or obesity risk behavior. Alternatively, each additional point on the family violence scale is associated with 20% higher odds of substance use but not risky sexual behavior or obesity risk behavior.

Conclusions

Childhood exposure to violent contexts is associated with risky adolescent health behaviors, but the associations are context and behavior specific. After including covariates, we find no association between childhood exposure to violent contexts and obesity risk behavior.

Keywords: violence, domestic violence, community violence, health behavior, risky sexual behavior, substance use, obesity risk behavior, children, adolescents, Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study

Adolescents who have unprotected sex, use tobacco, abuse alcohol, or become obese are at increased risk of morbidities and preventable death[1]. Therefore, examining the social determinants of adolescent health behavior is critical to developing a better understanding of health disparities[2]. Growing up in a violent environment is one aspect of childhood adversity that is understudied with regard to its consequences for adolescent health. Though a large literature has documented that childhood victims of violence suffer a range of negative consequences[3], less is known about the consequences of exposure to indirect violence (defined as witnessing violent acts, hearing about violence from others and/or interacting with persons and institutions affected by violence).

Though most people who live in violent environments do not become victims of violence[4], indirect exposure to violence may affect health and health behaviors by creating physical and psychological stress[3,5–7]; diminishing cognitive performance, attention, and impulse control[8,9]; and changing the perceived costs and benefits of risky behavior[10]. Additionally, the presence of violence may create structural changes in the institutions on which children and adolescents depend. Violence in the family may negatively affect parenting quality and parent-child attachment [11], while violence in the community may undermine neighborhood social organization (e.g. social cohesion and informal control of behavior) and positive socialization (via peer networks)[10]. In particular, the chronic stress resulting from exposure to violent contexts is likely to elicit subsequent coping behaviors that create pleasurable sensations or a sense of escape[12]. The leading causes of preventable morbidity and mortality fall within this range of coping behaviors: risky sexual behavior, substance use, overeating, and physical inactivity[13].

Despite the range of pathways through which violent contexts are likely to affect behavior, few studies have investigated whether childhood exposure to violent contexts matters for risky adolescent health behavior. In two clinical samples of girls, a retrospective report of ever witnessing violent acts was associated with unsafe sexual activity[14], having a risky sexual partner, using drugs or alcohol before sexual activity, and using tobacco or marijuana[15]. Similarly, in the 1995 National Survey of Adolescents retrospective report of witnessing violent acts was associated with substance abuse among 12- to 17-year-old adolescents[16]. With regard to violent acts that occurred in the home, ever witnessing domestic violence was associated with higher odds of overweight/obesity in a small sample of adolescents[17], and a large national survey found that adolescent girls (but not boys) who retrospectively reported ever wanting to leave home due to violence had higher rates of regular smoking and drinking than their peers[18]. However, the 2005 National Survey of Adolescents found an elevated risk of alcohol abuse and non-experimental drug use among adolescents who witnessed violent acts in their community but not among those who witnessed violent acts between parents[19].

Only one study has examined the prospective association of exposure to violence with risky adolescent health behavior. Among 1,655 adolescents from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, exposure to community (but not family or school) violence, including both indirect exposure and violent victimization, at ages 9–19 was associated with a higher frequency of marijuana use (but not alcohol use) three years later[20].

We extend this literature in three ways. First, we measure the extent of violence in the environments in which children grew up. This approach is distinct from the large literature investigating the negative consequences of violent victimization. Second, we examine both community and family violence and their prospective associations with three health behaviors: risky sexual behavior, substance use, and obesity risk behavior. To our knowledge, no other study has modeled a range of risky health behaviors as a function of exposure to violence across multiple contexts. Finally, we use prospective data from a longitudinal, population-based birth cohort study.

Based on theory related to stress and decision-making, we hypothesize that higher levels of childhood exposure to violent contexts will be associated with risky adolescent health behavior. Because violence may also affect behavior through an additional set of institution-specific mechanisms, such as by changing family or community functioning, we do not assume that family and community violence will be similarly associated with all risky health behaviors. Indeed, violence at different ecological levels operates through distinct pathways and is likely to have unique implications for particular health behaviors. For example, family violence is believed to interfere with adolescents’ ability to develop trust in intimate relationships[11], which may affect sexual health behavior. Additionally, growing up in an unsafe community decreases children’s opportunities for outdoor exercise[21,22], an important component of obesity risk behavior. By examining multiple violent contexts and several risky health behavior outcomes, we aim to provide insight into the connection between childhood experiences and adolescent health behavior.

METHODS

Data

The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) is a population-based, birth cohort study of 4,898 children born between 1998–2000 in twenty large American cities (population over 200,000). Because FFCWS oversampled non-martial births, the study includes a large and diverse sample of children from low-income families and neighborhoods. Sample recruitment is described in Reichman et al.[23]; subsequent data collection procedures are documented at https://fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/documentation. The Institutional Review Boards of Princeton University and Columbia University approved data collection.

Of the 3,444 adolescents who participated in the year 15 survey, 143 were excluded from analyses because they did not answer questions about the outcomes of interest. Another 456 adolescents were excluded because their mothers did not participate in either the age 5 or age 9 interview and therefore did not provide any information on violence predictors at one or both of these ages. An additional 143 cases were dropped because mothers reported that the child lived with them less than half the time at age 5, age 9, or both. Finally, 18 of the remaining adolescents were excluded because their mothers did not answer questions about one or more indicator of violence at both ages 5 and 9. These exclusions resulted in a final sample size of 2,684. Table A1 compares this analytic sample to the baseline and 15-year samples.

We used multivariate imputation using chained equations (M = 20) to impute missing data on covariates. Violence indicators were only imputed for cases that had data on a given indicator at either age 5 or age 9 but were missing a value at the other wave. We also limited analyses to a sample created using listwise deletion (N = 1,414) and found results to be substantively unchanged.

Measures

Each measure is described in Table 1, including the source of the measure, the time frame to which it refers, and its prevalence or mean.

Table 1.

Description of Analytic Sample

| Source | Time frame | Percent | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Health behaviors | ||||

| Risky sexual behavior | ||||

| No condom at first sex | Teen, 15-year | Ever | 3.17 | |

| Multiple sexual partners | Teen, 15-year | Ever | 10.13 | |

| First sex before age 14 | Teen, 15-year | Ever | 5.70 | |

| Any risky sexual behavior | 12.63 | |||

| Substance use | ||||

| Drugs | Teen, 15-year | Ever | 21.31 | |

| Smoked entire cigarette | Teen, 15-year | Ever | 4.77 | |

| Drank entire drink | Teen, 15-year | Ever | 15.57 | |

| Any substance use | 27.50 | |||

| Obesity risk behavior | ||||

| Fast food > 2x/week | Teen, 15-year | Typical week | 22.54 | |

| Sweetened drinks >2x/day | Teen, 15-year | Typical day | 35.99 | |

| Vigorous exercise <3x/week | Teen, 15-year | Typical week | 40.95 | |

| Any obesity risk behavior | 68.78 | |||

| Exposure to violence | ||||

| Community violence | ||||

| County violent crime rate greater than 2x national | ||||

| 5-year residence | FBI UCR | Interview year | 30.82 | |

| 9-year residence | FBI UCR | Interview year | 23.84 | |

| Afraid to let child outside because of violence | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Ever | 15.53 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Ever | 18.64 | |

| Gangs are a problem in neighborhood | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Current | 13.51 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Current | 15.64 | |

| Saw someone get beat up in community | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Past year | 30.84 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Past year | 22.74 | |

| Saw someone get attacked with weapon in community | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Past year | 9.81 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Past year | 7.60 | |

| Saw someone get shot at in community | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Past year | 5.97 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Past year | 5.59 | |

| Any community violence | 68.55 | |||

| Community violence score | 1.99 | |||

| Family violence | ||||

| Child saw physical fight of mother and partner | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Past two years | 5.85 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Past four years | 4.59 | |

| Partner slaps or kicks mother | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Past year | 0.67 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Past year | 0.83 | |

| Partner hits mother | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Past year | 0.37 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Past year | 0.61 | |

| Partner throws objects at mother | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Past year | 0.97 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Past year | 1.06 | |

| Partner pushes/grabs/shoves mother | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Past year | 1.68 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Past year | 1.70 | |

| Partner keeps mother from seeing family/friends | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Past year | 6.89 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Past year | 5.01 | |

| Partner keeps mother from going to work/school | ||||

| 5-year | Mother | Past year | 2.72 | |

| 9-year | Mother | Past year | 1.41 | |

| Any family violence | 20.51 | |||

| Family violence score | 0.33 | |||

| Other covariates | ||||

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Child age | Teen, 15-year | n/a | 15.50 | |

| Child male | Medical records, birth | n/a | 51.19 | |

| Child low birth weight | Medical records, birth | n/a | 8.95 | |

| Infant temperament | Mother, 1-year | Current | 2.56 | |

| Parent characteristics | ||||

| Mother’s race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | Mother, birth | n/a | 21.86 | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | Mother, birth | n/a | 50.21 | |

| Hispanic | Mother, birth | n/a | 24.35 | |

| Other race/ethnicity | Mother, birth | n/a | 3.58 | |

| Mother’s education | ||||

| Less than high school | Mother, birth | Current | 29.74 | |

| High school or GED | Mother, birth | Current | 31.32 | |

| Some college | Mother, birth | Current | 26.62 | |

| College graduate | Mother, birth | Current | 12.31 | |

| Mother’s age | Mother, birth | Current | 25.34 | |

| Mother depressed | Mother, 1-year | Past year | 12.16 | |

| Mother’s substance use | ||||

| Any cigarette use | Mother, 1-year | Past year | 25.33 | |

| Any alcohol use | Mother, 1-year | Past year | 34.41 | |

| Any drug use | Mother, 1-year | Past year | 1.91 | |

| Mother’s weight status | ||||

| Normal weight | Mother, 3-year | Current | 26.12 | |

| Underweight | Mother, 3-year | Current | 2.2 | |

| Overweight | Mother, 3-year | Current | 28.64 | |

| Obese | Mother, 3-year | Current | 43.04 | |

| Mother’s cognitive ability | Mother, 3-year | Current | 6.89 | |

| Household poverty ratio | Mother, birth | Past year | 1.15 | |

| Biological parents’ relation | ||||

| Married | Mother, birth | Current | 25.71 | |

| Cohabiting | Mother, birth | Current | 34.86 | |

| No relationship | Mother, birth | Current | 39.43 | |

| Neighborhood characteristics | ||||

| Average tract poverty rate | Census | 2000; 2005–09 | 19.72 | |

Note: One hundred twenty-nine cases in the analytic sample had dates of first sexual intercourse which could only be narrowed to a 12-month window that included their fourteenth birthday; for these cases, we took the midpoint of the window and then scored the case based on whether that date was before or after the adolescent’s fourteenth birthday.

At the 5-year study wave, questions about mothers seeing someone get beat up, attached with a weapon, or shot at did not explicitly specify “in community” in the question prompt.

Risky Health Behaviors

Our outcomes are three risky health behaviors: risky sexual behavior, substance use, and obesity risk behavior. For each behavior, we created a dichotomous indicator of whether the adolescent reported engaging in one or more (1) or none (0; reference) of the relevant behaviors. Risky sexual behavior (13% of sample) included whether the adolescent failed to use a condom at first sex, had multiple sexual partners, or had sexual intercourse before age 14. Substance use (28% of sample) was measured by whether the adolescent had tried any illegal drugs, smoked an entire cigarette, or drunk an entire alcoholic beverage more than 2 or 3 times when not with parents. Obesity risk behavior (69% of sample) was measured by whether the adolescent drank more than two non-diet sweetened drinks per day, ate fast food more than twice per week, or engaged in physical exercise less than three times per week (based on recommendations of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services[24]). Alternative analyses examine the adolescent’s overweight and obesity, based on self-reported or objectively measured (if available) height and weight.

Exposure to Violent Contexts

The predictors of interest are exposure to community and family violence. Community violence includes six indicators; family violence includes seven indicators. All indicators were measured at both ages 5 and 9.

Community violence

The violent crime rate of the child’s county of residence was measured using FBI Uniform Crime Report statistics. To identify exposure to high levels of violent crime, we created a dichotomous indicator of whether the violent crime rate in the child’s county of residence in the interview year was above two times the national average for the same year. We also included mothers’ reports of whether they were ever afraid to let the child outside because of violence, whether gang violence was currently a problem in the child’s residential neighborhood, and whether in the last year they had seen somewhat get beat up, attacked with a weapon, or shot at in their communities. Sixty-nine percent of adolescents were exposed to at least one indicator of community violence. Figure A1 shows the community violence score distribution

Family violence

The most prevalent form of family violence in our sample is the mother’s report that the child witnessed a physical fight between her and a romantic partner (the child’s biological father or a different partner). Other indicators of family violence come from the mother’s report of experiencing specific types of interpersonal violence victimization in the past year, including whether a partner slapped or kicked; hit; threw objects at; or pushed, grabbed, or shoved her, as well as whether the partner prevented her from seeing family/friends or going to work/school. We created a series of dichotomous measures of whether the child’s mother did or did not report each indicator of family violence. Twenty-one percent of adolescents were exposed to at least one indicator of family violence at either age 5 or age 9. Figure A2 shows the family violence score distribution.

Other Covariates

To account for factors that may influence both exposure to violence and risky health behavior, we include as covariates a range of child/adolescent, parent, and neighborhood characteristics.

Adolescent characteristics

Adolescent characteristics include age, gender, low birth weight, and infant temperament. Infant temperament is measured using a subset of questions from the Emotionality and Shyness sections of the EAS Temperament Survey for Children[25], including to what extent the child tends to be shy, often fusses and cries, gets upset easily, is very sociable (reverse-coded), or is very friendly with strangers (reverse-coded) with scores ranging from 1 to 5 (Chronbach’s alpha = .51) and with higher scores indicating that a characteristic is true of the child.

Parent characteristics

Demographic characteristics of the adolescent’s mother include race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other race/ethnicity), educational attainment (less than high school degree, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate), and age, in years. Whether the mother was likely depressed when her child was age 1 was assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview – Short Form, Section A[26], scored with adjustments as per Walters, Kessler, Nelson, and Mroczek[27], and mothers reported their past-month substance use, including cigarette use, alcohol use, and drug use, at the same wave. When the child was 3 years old, in-home measurements of height and weight were collected for a subset of mothers; the remainder of mothers reported their own height and weight and we used this measure to categorize mothers as normal weight, underweight, overweight, or obese. Mothers’ cognitive ability was measured using the Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised (WAIS-R) Similarities subtest[28]. We also control for household income as a percent of the federal poverty line and parents’ relationship status (married, cohabiting, or no relationship) at the time of birth.

Neighborhood characteristics

Our models control for the proportion of households in the child’s census tract with incomes below the poverty line at ages 5 (from the 2000 Census) and 9 (from the 2005–2009 American Community Survey), averaged for the two ages.

Analytic Strategy

We estimate the extent to which exposure to violent contexts at ages 5 and 9 is associated with each of three risky health behaviors – risky sexual behavior, substance use, and obesity risk behavior – at age 15 using logistic regression in the form

In these analyses, α is the model intercept, X1 is the violence score, and, in models with all covariates, X2 is a vector of child, family, and neighborhood characteristics (covariates with the vector of coefficients β2).

RESULTS

Results are reported in Tables 2 and 3 (all coefficients for Table 3 are available in Table A2).

Table 2.

Bivariate Association of Childhood Exposure to Violent Contexts and Risky Adolescent Health Behavior

|

|

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risky sexual behavior | Substance use | Obesity risk behavior | ||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Community violence score | 1.200*** (1.143, 1.259) | 1.083*** (1.042, 1.127) | 1.129*** (1.082, 1.178) | |||

| Family violence score | 1.057 (0.924, 1.210) | 1.206*** (1.093, 1.330) | 1.071 (0.964, 1.190) | |||

| Covariates | ||||||

| Constant | 0.095*** (0.080, 0.113) | 0.142*** (0.125, 0.161) | 0.321*** (0.285, 0.362) | 0.355*** (0.323, 0.389) | 1.754*** (1.568, 1.961) | 2.155*** (1.973, 2.353) |

| AIC | 1986.9 | 2039.44 | 3144.87 | 3147.58 | 3302.6 | 3335.14 |

Note: Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from logit models.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 3.

Adjusted Association of Childhood Exposure to Violent Contexts and Risky Adolescent Health Behavior

| Risky sexual behavior | Substance use | Obesity risk behavior | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Community violence score | 1.080* (1.016, 1.148) | 1.079* (1.015, 1.147) | 1.045† (0.995, 1.097) | 1.038 (0.988, 1.091) | 1.013 (0.962, 1.066) | 1.011 (0.960, 1.064) | |||

| Family violence score | 1.040 (0.893, 1.212) | 1.021 (0.875, 1.192) | 1.195*** (1.076, 1.327) | 1.187** (1.068, 1.319) | 1.050 (0.941, 1.171) | 1.048 (0.939, 1.169) | |||

| Covariates | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Constant | 0.029*** (0.016, 0.053) | 0.034*** (0.018, 0.061) | 0.029*** (0.016, 0.053) | 0.278*** (0.188, 0.410) | 0.294*** (0.201, 0.429) | 0.272*** (0.184, 0.402) | 2.886*** (1.977, 4.213) | 2.934*** (2.038, 4.222) | 2.872*** (1.967, 4.194) |

| AIC | 1792.02 | 1797.92 | 1793.93 | 3035.68 | 3028.02 | 3027.65 | 3201.67 | 3201.17 | 3202.95 |

Note: Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from logit models.

Covariates include child’s age, child sex, whether the child was born with a low birth weight, mother’s race/ethnicity, mother’s educational attainment, mother’s age, mother’s depression, mother’s substance use, mother’s weight status, mother’s cognitive ability, household poverty ratio, biological parents’ relationship, and census tract poverty rate.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Community Violence

Focusing first on community violence, bivariate associations show a strong, positive association between childhood exposure to violent community contexts and risky adolescent health behaviors. Each additional point on the community violence score is associated with about 20% higher odds of risky sexual behavior (Table 2, Model 1), 8% higher odds of substance use (Table 2, Model 3), and 13% higher odds of obesity risk behavior (Table 2, Model 5).

After adjusting for covariates, each additional point on the violence score is associated with approximately 8% higher odds of risky sexual behavior in adolescence (Table 3, Model 1). This coefficient changes very little when family violence is added to the model (Table 3, Model 3). Each additional point on the community violence score is also associated with about 5% higher odds of substance use (Table 3, Model 4), but the coefficient is no longer statistically significant when both types of violence are included in the model (Table 3, Model 6). Finally, after including covariates there is no significant association between the community violence score and obesity risk behavior (Table 3, Model 7), either alone or when the family violence score is included in the model (Table 3, Model 9).

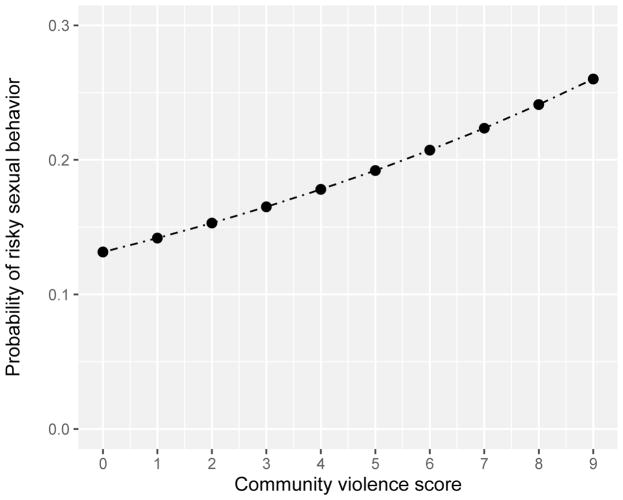

Figure 1 shows the predicted probabilities of risky sexual behavior by level of exposure to community violence (obtained using Table 3, Model 3). Comparing adolescents with a community violence score of 0 to those with a score of 9, the predicted probability of risky sexual behavior approximately doubles from 13% to 26%.

Figure 1.

Predicted Level of Risky Sexual Behavior as a Function of Community Violence Score

Note: Covariates are held at their means for continuous variables and modes for dichotomous or categorical variables.

Family Violence

Next we examine the association of childhood exposure to family violence with risky adolescent health behavior. In bivariate analyses, each additional point on the family violence score is associated with 21% higher odds of substance use (Table 2, Model 4); there is no statistically significant association with risky sexual behavior (Table 2, Model 2) or obesity risk behavior (Table 2, Model 6).

In models that include covariates, the pattern is similar. The family violence score is not statistically significantly associated with risky sexual behavior (Table 3, Models 2 and 3) or obesity risk behavior (Table 3, Models 8 and 9). However, each point on the family violence score is associated with about 19% higher odds of substance use (Table 3, Model 5). This association diminishes by less than one percentage point when community violence is added to the model (Table 3, Model 6).

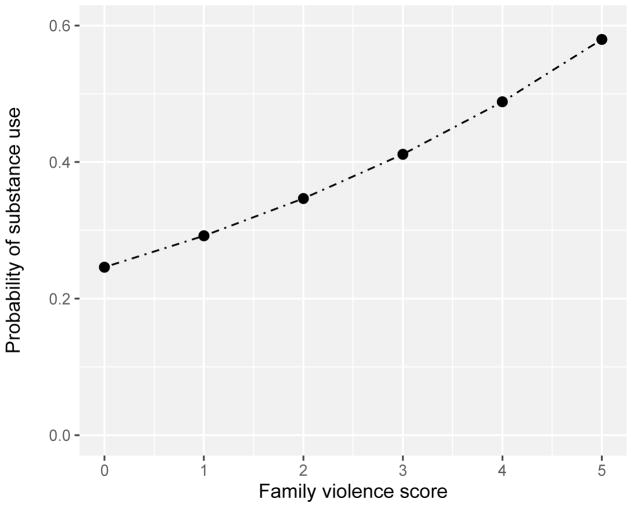

Figure 2 shows the predicted probabilities of substance use by level of exposure to family violence (obtained using Table 3, Model 6). Adolescents who grew up in families with no violence are predicted to have a 22% probability of substance use, while adolescents who have a family violence score of five have a 58% chance of substance use.

Figure 2.

Predicted Level of Substance Use as a Function of Family Violence Score

Note: Covariates are held at their means for continuous variables and modes for dichotomous or categorical variables.

Alternative Model Specifications

Specific Risky Health Behavior Outcomes

Because the risky health behavior outcomes include multiple indicators, it is possible that associations between exposure to violent contexts and the outcomes differ for some indicators. Table A3 shows models of each individual risky health behavior indicator. We find that associations are quite comparable to those presented in the main analyses; exposure to community violence is associated with higher odds of both first sex before age 14 and having multiple sexual partners, exposure to family violence is associated with elevated risk of drug and alcohol use, and no type of violence is associated with obesity risk behavior indicators. We found no association between violence exposure and not using a condom at first sex or smoking an entire cigarette. However, these two outcomes have the lowest prevalence of all of the outcomes (3.17% and 4.77% of the analytic sample, respectively), and thus associations are estimated less precisely than for indicators. Consequently, we do not interpret these findings as compelling evidence of differential effects between indicators.

Alternative Obesity-Related Outcomes

To test whether our failure to identify a statistically significant association between the violence scores and obesity risk behavior was an artifact of our particular obesity-related measures, we considered other frequency cutoffs for the obesity risk indicators. We also modeled the adolescent’s overweight and obesity directly, both with and without controlling for obesity risk behavior. We found no statistically significant association of childhood exposure to violence contexts with adolescent obesity risk behavior or weight status.

Nonlinearities

To assess potential nonlinearities in the association between exposure to violence and behavioral outcomes[29], we used two methods. First, we allowed the association between one type of violent environment and risky health behavior to be moderated by the other using a community violence score * family violence score interaction term. Second, we added a quadratic term for the violence score to our models, to test whether high levels of exposure to violence desensitized children to the violent contexts. We found no evidence of either nonlinearity.

Moderators

Finally, we considered models accounting for gender or age moderation. The association of exposure to or experience of violence with behavioral outcomes may differ by gender[18], and most studies of risky sexual behavior have relied on samples of girls only[14,15]. We found no evidence of a gender difference. Additionally, exposure to violence at different ages or developmental stages may have different consequences[30]. When we considered models in which the violence was measured at only age 5 versus only age 9, results were similar, with odds ratios somewhat larger at age 5 than at age 9.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to demonstrate a prospective link between exposure to violence and risky health behavior across domains. Using a diverse population-based sample, we find that childhood exposure to violent contexts is associated with higher levels of risky health behavior six to ten years later at age 15. Controlling for child, family, and neighborhood characteristics, community violence (but not family violence) is associated with risky sexual behavior, whereas family violence (but not community violence) is associated with substance use. Neither family nor community violence is associated with obesity risk behavior, conditional on covariates. The lack of association of exposure to violence with obesity risk behavior may indicate no meaningful effect. Alternatively, measurement error and the ubiquity of obesity risk behavior may limit our ability to identify a statistically significant association.

We extend prior research by examining how childhood exposures to violent family and community contexts are associated with a range of heath behavior outcomes[31]. First, to our knowledge, this the first population-based longitudinal study to estimate the association between exposure to multiple violent contexts and several adolescent health behaviors. Notably, our estimates adjust for parental substance use and obesity. Second, our work develops the substantial literature on the consequences of adverse childhood experiences for health behaviors[32] by including community violence and by using a prospective research design[16,19]. Third, we consider three risky health behaviors, whereas prior longitudinal work has considered substance use only[20]. Although the differences described above make it difficult to compare our findings with those of previous studies, our study provides evidence that childhood exposure to violent contexts is the type of stressor that may lead to subsequent risky health behaviors[13].

This study also has several limitations. First, we are not able to measure violence in the school or peer group. Future research should incorporate these key childhood contexts. Second, only one indicator of family violence (whether the child witnessed the mother and her partner having a physical fight) captures violence in which the partner is the victim; other family violence indicators measure only the mother’s victimization. Thus, our measure of family violence is likely an underestimate. Third, we could not test how exposure to violent contexts in early childhood or adolescence matter for risky adolescent health behavior. Associations may differ depending on developmental period of exposure. Fourth, our violence scores give equal weight to all indicators of violence. It is possible that some exposures to violence are more important for later risky health behaviors than are others, and future work should assess these differences. Fifth, we do not have measures of all possible risky health behaviors; notably, we do not know if adolescents engage in substance use simultaneously with risky sexual behavior[15]. Sixth, although our study design is prospective and controls for many potential confounders, our findings cannot be interpreted as causal. Finally, our sample is largely urban and disadvantaged, and this population may be at higher risk of exposure to violence (particularly community violence) than more rural or advantaged populations. We note, however, that the high level of exposure to violence that we observe is not inconsistent with national prevalence estimates of children’s exposure to violence[33].

Future research should also investigate the mechanisms and moderators of the association between exposure to violent contexts and risky health behaviors. Determining the mechanisms through which these associations come about will require assessing the intermediary physiological and psychological sequela of exposure to violence that affect health behavior decision-making in pathways specific to particular violent contexts and specific risky health behaviors. It is also important to identify the individual, family, and community factors that may foster resilience among children embedded in violent contexts, in order to design interventions to mitigate the consequences of exposure to violence.

Our findings underscore the importance of studying violence as an aspect of context that produces health. Moreover, our results suggest that associations between violence and risky behaviors are context- and domain-specific. Reducing childhood exposure to violence in communities and families has the potential to mitigate a substantial portion of risky adolescent sexual behavior and adolescent substance use, respectively. Because violence is an important pathway through which poor health and socioeconomic outcomes are reproduced across generations[34], policies that reduce childhood exposure to violence are ultimately likely to facilitate greater long-term health and social mobility.

Supplementary Material

Implications and Contribution.

Using a national sample of 2,684 children followed from birth in 1998–2000 to age 15, this study finds that childhood exposure to violent communities predicts higher odds of risky adolescent sexual behavior and that childhood exposure to family violence predicts higher odds of adolescent substance use.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01HD36916, R01HD39135, R01HD40421, and P2CHD047879; and a consortium of private foundations. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declarations: The authors have no conflicts of interest or sources of financial support to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sarah James, Department of Sociology and Office of Population Research, Princeton University.

Louis Donnelly, Office of Population Research and Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing, Princeton University.

Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Teachers College and The College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University.

Sara McLanahan, Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing, Princeton University.

References

- 1.Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, et al. Adolescence: A Foundation for Future Health. Lancet. 2012;379:1630–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris KM. An Integrative Approach to Health. Demography. 2010;47:1–22. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Margolin G, Gordis EB. The Effects of Family and Community Violence on Children. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:445–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman GM, Posick C. Risk Factors for and Behavioral Consequences of Direct Versus Indirect Exposure to Violence. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:178–88. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aiyer SM, Heinze JE, Miller AL, et al. Exposure to Violence Predicting Cortisol Response During Adolescence and Early Adulthood: Understanding Moderating Factors. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43:1066–79. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0097-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mrug S, Loosier PS, Windle M. Violence Exposure Across Multiple Contexts: Individual and Joint Effects on Adjustment. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78:70–84. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zinzow HM, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick H, et al. Prevalence and Mental Health Correlates of Witnessed Parental and Community Violence in a National Sample of Adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2009;50:441–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharkey PT. The Acute Effect of Local Homicides on Children’s Cognitive Performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:11733–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000690107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharkey PT, Tirado-Strayer N, Papachristos AV, et al. The Effect of Local Violence on Children’s Attention and Impulse Control. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2287–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harding DJ. Collateral Consequences of Violence in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods. Soc Forces. 2009;88:757–84. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The Impact of Exposure to Domestic Violence on Children and Young People: A Review of the Literature. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brady SS, Donenberg GR. Mechanisms Linking Violence Exposure to Health Risk Behavior in Adolescence: Motivation to Cope and Sensation Seeking. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:673–80. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000215328.35928.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mezuk B, Abdou CM, Hudson D, et al. “White Box” Epidemiology and the Social Neuroscience of Health Behaviors: The Environmental Affordances Model. Soc Ment Health. 2013;3:79–95. doi: 10.1177/2156869313480892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson HW, Woods BA, Emerson E, et al. Patterns of Violence Exposure and Sexual Risk in Low-Income, Urban African American Girls. Psychol Violence. 2012;2:194–207. doi: 10.1037/a0027265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berenson AB, Wiemann CM, McCombs S. Exposure to Violence and Associated Health-Risk Behaviors Among Adoelscent Girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1–15. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.11.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, et al. Violence and Risk of PTSD, Major Depression, Substance Abuse/Dependence, and Comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gooding HC, Milliren C, Austin SB, et al. Exposure to Violence in Childhood is Associated with Higher Body Mass Index in Adolescence. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;50:151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simantov E, Schoen C, Klein J. Health-Compromising Behaviors: Why Do Adolescents Smoke or Drink? Identifying Underlying Risk and Protective Factors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:1025–33. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.10.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zinzow HM, Ruggiero KJ, Hanson RF, et al. Witnessed Community and Parental Violence in Relation to Substance Use and Delinquency in a National Sample of Adolescents. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:525–33. doi: 10.1002/jts.20469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright EM, Fagan AA, Pinchevsky GM. The Effects of Exposure to Violence and Victimization across Life Domains on Adolescent Substance Use. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37:899–909. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolbert Kimbro R, Brooks-Gunn J, McLanahan S. Young Children in Urban Areas: Links among Neighborhood Characteristics, Weight Status, Outdoor Play, and Television Watching. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:668–76. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molnar BE, Gortmaker SL, Bull FC, et al. Unsafe to Play? Neighborhood Disorder and Lack of Safety Predict Reduced Physical Activity Among Urban Children and Adolescents. Am J Heal Promot. 2004;18:378–86. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.5.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, et al. Fragile Familes: Sample and Design. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2001;23:303–26. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Services USD of H and H. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathiesen KS, Tambs K. The EAS Temperament Questionnaire — Factor Structure, Age Trends, Reliability, and Stability in a Norwegian Sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 1999;40:431–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, et al. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1998;7:171–85. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walters EE, Kessler RC, Nelson RC, et al. Scoring the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised (WAIS-R Manual) 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foster H, Brooks-Gunn J. Toward a Stress Process Model of Children’s Exposure to Physical Family and Community Violence. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2009;12:71–94. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0049-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osofsky JD. The Impact of Violence on Children. Futur Child. 1999;9:33–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saunders BE. Understanding Children Exposed to Violence: Toward an Integration of Overlapping Fields. J Interpers Violence. 2003;18:356–76. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mersky JP, Topitzes J, Reynolds AJ. Impacts of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Health, Mental Health, and Substance Use in Early Adulthood: A Cohort Study of an Urban, Minority Sample in the U. S Child Abus Negl. 2013;37:917–25. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finkelhor D, Turner Ha, Shattuck A, et al. Prevalence of Childhood Exposure to Violence, Crime, and Abuse. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:746–54. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aizer A. The Role of Children’s Health in the Intergenerational Transmission of Economic Status. Child Dev Perspect. 2017;11:167–72. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.