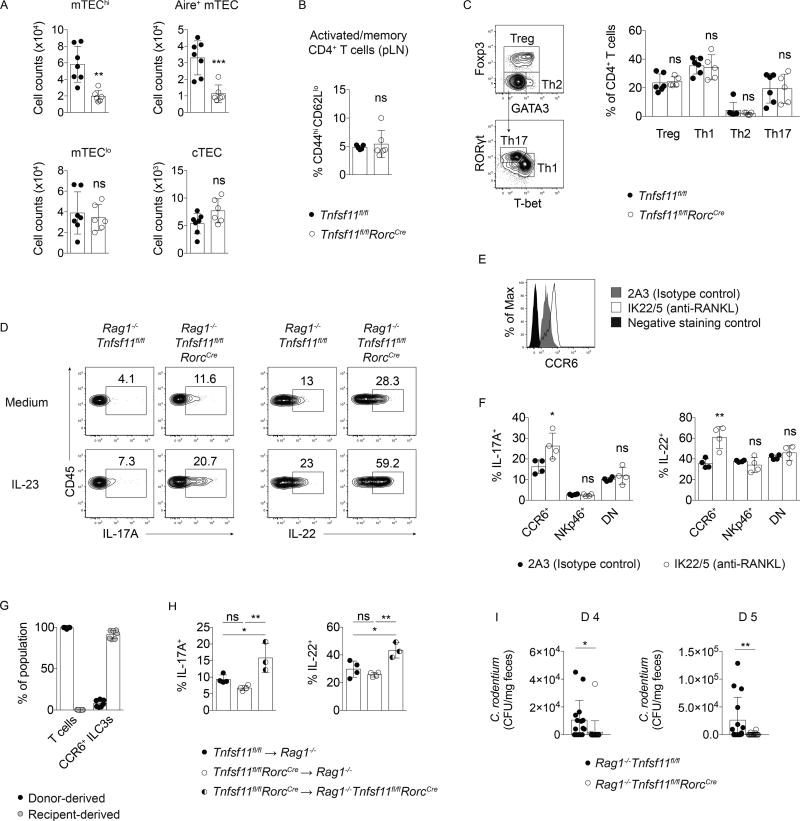

Figure 3. RANKL-deficient T cells are not necessary or sufficient to drive ILC3 hyperresponsiveness.

(A) Thymic epithelial cell (TEC) counts in Tnfsf11fl/flRorcCreand Tnfsf11fl/fl control thymi. TECs were identified as Epcam+CD45− cells that either expressed Ly51 (cTEC); low MHCII and CD80 (mTEClo); high MHCII and CD80 (mTEChi); or high MHCII, CD80, and AIRE (AIRE+ mTEC) (n=6–7). (B) Frequencies of CD44hiCD62Llo CD4+ T cells from pooled lymph nodes (n=5–6). (C) Gating strategy and helper T cell frequencies in small intestine lamina propria (n=4). (D) IL-17A and IL-22 production in Rag1−/−Tnfsf11fl/flRorcCre and Rag1−/−Tnfsf11fl/fl mice. (E) CCR6 expression and (F) IL-17A and IL-22 production by in vitro stimulated small intestine lamina propria CCR6+ ILC3s from Rag1−/− mice injected with a blocking antibody to RANKL (n=4). (G) Percent donor- and receipient-derived small intestine lamina propria CCR6+ ILC3s in chimeras. (n=7). (H) IL-17A and IL-22 production in small intestine lamina propria CCR6+ ILC3s from chimeras after in vitro stimulation with IL-23 (n=3–4). (I) C. rodentium in feces of infected mice d 4 and d 5 post-inoculation (n=15–20). Bars indicate mean (+/− s.d). *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001. Data are pooled from two (A, B, G) or three (I) independent experiments, or are representative of two independent experiments (C–F).