Abstract

Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease is a rare auto-somal dominant syndrome that is the main cause of inherited clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), which generally occurs in the form of multiple recurrent synchronized tumors. Affected patients are carriers of a germline mutation in the VHL tumor suppressor gene. Somatic mutations of this gene are also found in sporadic ccRCC and numerous pan-genomic studies have reported a dysregulation of microRNA (miRNA) expression in these sporadic tumors. In order to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of VHL-associated ccRCC, particularly in the context of multiple tumors, the present study characterized the mRNA and miRNA transcriptome through an integrative analysis compared with sporadic renal tumors. In the present study, two series of ccRCC samples were used. The first set consisted of several samples from different tumors occurring in the same patient, for two independent patients affected with VHL disease. The second set consisted of 12 VHL-associated tumors and 22 sporadic ccRCC tumors compared with a pool of normal renal tissue. For each sample series, an expression analysis of miRNAs and mRNAs was conducted using microarrays. The results indicated that multiple tumors within the kidney of a patient with VHL disease featured a similar pattern of miRNA and gene expression. In addition, the expression levels of miRNA were able to distinguish VHL-associated tumors from sporadic ccRCC, and it was identified that 103 miRNAs and 2,474 genes were differentially expressed in the ccRCC series compared with in normal renal tissue. The majority of dysregulated genes were implicated in 'immunity' and 'metabolism' pathways. Taken together, these results allow a better understanding of the occurrence of ccRCC in patients with VHL disease, by providing insights into dysregulated miRNA and mRNA. In the set of patients with VHL disease, there were few differences in miRNA and mRNA expression, thus indicating a similar molecular evolution of these synchronous tumors and suggesting that the same molecular mechanisms underlie the pathogenesis of these hereditary tumors.

Keywords: von Hippel-Lindau disease, clear-cell renal cell carcinoma, miRNA and mRNA profiling, integrative analyses

Introduction

Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease is an autosomal dominant hereditary syndrome caused by germline mutations in the VHL tumor suppressor gene, which is located on chromosome 3p25-26. The clinical phenotype of VHL disease is characterized by the development of a panel of benign and malignant, highly vascularized tumors in several organ systems. One of the major clinical manifestations is clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). The emergence of tumors follows the inactivation of the remaining wild-type allele. Somatic VHL inactivation is also a hallmark of the majority of cases of sporadic ccRCC, and insights into VHL gene function have resulted in the use of antiangiogenic targeted therapies, which are now first line in the treatment of advanced renal tumors (1). Fuhrman's nuclear grade is the cornerstone of the prognostic classification of ccRCC and is based on increasing nuclear size, irregularity and nucleolar prominence (2).

In the last few years, numerous pan-genomic studies [comparative genomic hybridization-array, and gene and microRNA (miRNA/miR) expression profiles] have well characterized sporadic ccRCC (3–7). However, few studies have been published in the field of VHL-associated ccRCC (8,9). Fisher et al demonstrated that kidney tumors developing from a germline VHL mutation exhibit complementarity of the evolutionary principles of contingency and convergence. Notably, reduced mutation burden and limited evidence of intra-tumor heterogeneity were detected in these tumors (10). To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has focused on miRNA profiles in VHL-associated renal tumors compared with in sporadic ccRCC; these two entities are considered similar but no transcriptomic comparison study has been conducted to confirm this fact. The main function of miRNAs is to suppress the translation of target genes; however, they can also process mRNAs for cellular decay (11). Mature miRNAs have numerous targets, are often members of the same regulatory networks, and operate in regulatory feedback loops. These properties position them as fine-tuning modulators of set points in homeostatic processes in normal cells. It has previously been reported that discrete sets of miRNAs are induced and repressed in various types of cancer, and are specific to particular diagnoses and progression patterns, and predictive of responses to treatment. In cancer, aberrations in the expression of specific miRNAs may have well-defined tumor-suppressing or oncogenic functions (12). Furthermore, since a given miRNA has several targets, multiple pro-oncogenic or tumor-suppressing pathways are affected, and these pathways, in turn, regulate the miRNA expression in a feedback-loop mechanism (13). Studies regarding miRNA dysregulation in cancer have risen rapidly recently, including those in sporadic ccRCC (14,15).

The transcriptomic analysis of synchronous tumors occurring within the kidney in one patient offers a rare opportunity to investigate the evolution of tumors. In the present study, to better understand the biological processes implicated in the tumorigenesis of VHL-associated ccRCC, the transcriptomic (miRNA and mRNA) signature of VHL-associated tumors was determined using multiple tumor samples from two distinct patients who possessed several different primary kidney tumors. For comparison, the miRNA and mRNA profiles of 12 independent VHL-associated tumors were determined and were compared with the profiles of 22 sporadic renal tumors. The present study may provide information regarding the molecular pathogenesis of ccRCC in patients with VHL disease and offer possibilities for further molecular investigations.

Materials and methods

Patient samples and ethical consent

A total of 36 patients were recruited between 2002 and 2009. Their mean age at diagnosis was 54.9 years old. The sample series, which comprised two sets of 13 (from 2 patients) and 34 (from 34 patients) human ccRCC samples were obtained from the French Kidney Cancer Consortium coordinated by Professor Stéphane Richard (French National Network for Rare Cancers in Adults PREDIR Center, Bicêtre Hospital, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France). The present study was approved by the ethical committee of Bicêtre Hospital (Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France). Primary tumors, and for some cases adjacent non-tumor samples, were obtained from patients who underwent surgical tumor resection. All patients provided written informed consent prior to surgery for use of their tumors. Tumor samples were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen following surgery and were classified according to the Fuhrman nuclear grading system, after which they were grouped into low grade (grade 1+2) and high grade (grade 3+4) tumors (2).

The main clinical and genetic features of the patients, and tumor characteristics, are described in Table I. Part of the tumor series was previously reported (16). Differences in the numbers of samples are due to the lack of sufficient RNA quantity.

Table I.

Characteristics of tumor samples.

| Tumor number | Hospital | Sex | Age (years) | Histology | Fuhrman's grade | Grade class | VHL status | microRNA microarray analysis | Gene microarray analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First set | |||||||||

| 2203_T1 | Necker | M | 61 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 2203_T10 | Necker | M | 61 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 2203_T3 | Necker | M | 61 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 2203_T6 | Necker | M | 61 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 2203_T7 | Necker | M | 61 | VHL-ccRCC | 3 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 2203_T9 | Necker | M | 61 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 1674_T1 | Necker | F | 39 | VHL-ccRCC | 3 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 1674_T11 | Necker | F | 39 | VHL-ccRCC | 3 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 1674_T13 | Necker | F | 39 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | |

| 1674_T19 | Necker | F | 39 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 1674_T2 | Necker | F | 39 | VHL-ccRCC | 3 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 1674_T3 | Necker | F | 39 | VHL-ccRCC | 3 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 1674_T4 | Necker | F | 39 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| Second set | |||||||||

| 1919 | St-Joseph | F | 75 | Sporadic ccRCC | 2 | Low | Wild-type | Yes | Yes |

| 2040 | Necker | F | 45 | Sporadic ccRCC | 3 | High | Wild-type | Yes | Yes |

| 3042 | St-Joseph | M | 83 | Sporadic ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 3503 | St-Joseph | M | 59 | Sporadic ccRCC | 4 | High | Wild-type | Yes | Yes |

| 3554 | St-Joseph | M | 47 | Sporadic ccRCC | 3 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 3559 | St-Joseph | M | 61 | Sporadic ccRCC | 3 | High | Wild-type | Yes | Yes |

| 4320 | St-Joseph | F | 78 | Sporadic ccRCC | 3 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 4667 | St-Joseph | F | 70 | Sporadic ccRCC | 3 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 5290 | St-Joseph | F | 69 | Sporadic ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 5668 | St-Joseph | M | 69 | Sporadic ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 5835 | St-Joseph | M | 60 | Sporadic ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 5887 | St-Joseph | M | 85 | Sporadic ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 6517 | St-Joseph | M | 76 | Sporadic ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 6739 | St-Joseph | M | 53 | Sporadic ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 7294 | St-Joseph | F | 65 | Sporadic ccRCC | 4 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 7896 | St-Joseph | F | 70 | Sporadic ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 8527 | St-Joseph | F | 77 | Sporadic ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 9490 | St-Joseph | M | 67 | Sporadic ccRCC | 4 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 9671 | St-Joseph | F | 45 | Sporadic ccRCC | 4 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 40442 | St-Joseph | M | 56 | Sporadic ccRCC | 3 | High | Wild-type | – | Yes |

| 40815 | St-Joseph | M | 71 | Sporadic ccRCC | 3 | High | Wild-type | Yes | Yes |

| 40842 | St-Joseph | F | 77 | Sporadic ccRCC | 1 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 2132 | Necker | M | 34 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | – | Yes |

| 2920 | Bicêtre | M | 26 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 4573 | Bicêtre | M | 24 | VHL-ccRCC | 1 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 4734 | Bicêtre | M | 65 | VHL-ccRCC | 3 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 5205 | Necker | M | 27 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 6315 | Bicêtre | M | 35 | VHL-ccRCC | 3 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 6434 | Necker | F | 40 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 6600 | Necker | M | 23 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 7000 | Necker | F | 45 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 8156 | Necker | F | 40 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 8464 | Bicêtre | M | 28 | VHL-ccRCC | 2 | Low | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

| 50201 | Necker | M | 31 | VHL-ccRCC | 3 | High | Mutated | Yes | Yes |

ccRCC, clear-cell renal cell carcinoma; F, female; M, male; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau.

Tumor cryosections and total RNA extraction

All samples were frozen at −80°C prior to RNA extraction. The percentage of malignant tumor cell content was determined in the first and last sections obtained using a cryostat, and sections with >60% malignant tumor cell content were used for subsequent experimentation (mean of all the series: 83±12%). Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Nucleic acid concentration and purity were determined using NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA), and RNA quality was verified using a 2100 Bioanalyser (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) using an RNA integrity no. >6. The reference sample was based on a pool of RNA extracted from all normal adjacent tissues available, which consisted of 17 renal tissue samples from patients with sporadic ccRCC, and was used for all analyses.

miRNA and gene microarray expression analysis

Each sample was prepared according to the Agilents miRNA Microarray system protocol (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Total RNA (100 ng) was labeled and hybridized to Agilent human miRNA 8×15K microarrays v3 (AMADID 21827; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) containing 851 human and 88 human viral miRNAs, each replicated 16 times, and Agilent human genome 4×44K microarrays (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) for gene expression, according to the manufacturer's protocol. All processing methods used for miRNA analyses were performed on the Cy3 Median Signal in Agilent Feature software v10.7 (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). For gene expression, analyses were performed on the Cy3 and Cy5 Median signal in Agilent Feature software v10.7 (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Raw data files were extracted using functions in Bioconductor (17). Flagged spots, as well as control spots, were systematically removed, and data were log2 transformed. Quantile normalization was performed using the normalizeBetweenArray function from R package 'LIMMA' (version no. 3.34.9) (18). The median of each probe for a given miRNA was computed and the corresponding value was assigned to the miRNA. Data were then filtered according to the maximum number of missing values allowed for each miRNA (30%).

Hierarchical clusters were computed using the 'dist' function from R, using the 'Euclidian' method as a measure of distance. Hierarchical clustering was performed using the 'hclust' function from R using the distance matrix previously computed and Ward's method.

To assess differentially expressed miRNAs, the fold-changes and standard errors were initially estimated between two groups of samples by fitting a linear model for each miRNA with the 'lmFit' function of LIMMA package. Subsequently, empirical Bayes smoothing was applied to the standard errors in the linear model previously computed using the 'eBayes' function of LIMMA. To extract a table of the top-ranked genes from the linear model fit, the topTable function in LIMMA was utilized. The results were saved in a table file format.

BRB analyses were performed to compare the tumor groups and the reference group. miRNAs and genes that were significantly differentially expressed between the groups at P<0.05 using BRB ArrayTools v2 (https://brb.nci.nih.gov/BRB-ArrayTools/), as determined using two-way analysis of variance and multiple correction Benjamini-Hochberg test, were selected for further analysis. Significantly differentially expressed miRNAs were used to build a hierarchical cluster using Gene-E (https://software.broadinstitute.org/GENE-E/index.html). For biological interpretation of significant genes, the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) was employed to perform the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. Significant KEGG pathways (P<0.05) were selected in VHL-associated and sporadic ccRCC tumors.

Results

Patients and samples

The main characteristics of the two tumor sets used in the present study and individual patient data are reported in Table I. The first set consisted of several samples from multiple tumors obtained from two patients with VHL disease [Patient 2203, n=6; Patient 1674, n=7 (6 for miRNA analysis and 7 for mRNA analysis)]. The second set consisted of 12 VHL-associated renal tumors (11 for miRNA analysis and 12 for mRNA analysis) and 22 sporadic ccRCC tumors (21 for miRNA analysis and 22 for mRNA analysis) from 34 patients.

Lack of heterogeneity for miRNA and mRNA expression profiles between multiple tumors for the same patient with VHL disease

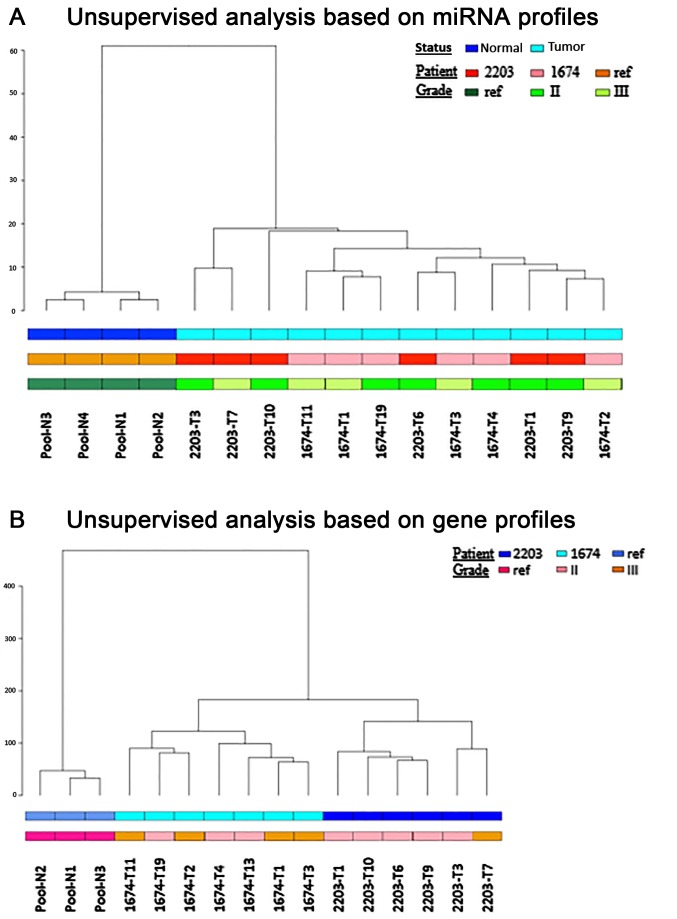

Patients affected with VHL disease can simultaneously develop several multifocal and bilateral tumors in the kidneys. The present study performed microarray gene and miRNA expression analyses on several samples from different tumors obtained from the same patient, for two independent patients (Patients 2203 and 1674). Firstly, unsupervised hierarchical clustering analyses were conducted on the miRNA and gene expression profiles. In both analyses, tumor samples were well separated from the normal renal tissue pool. In addition, unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the miRNA expression profiles was not able to discriminate between the two patients (Fig. 1A); however, unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the mRNA expression profiles was able to distinguish between the two patients; this may be explained by the different genetic background (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Unsupervised hierarchical analyses based on (A) miRNA profiles (euclidian distance, ward cluster, cor. cophenetic: 0.788) and (B) gene profiles (euclidian distance, ward cluster, cor. cophenetic: 0.922) in patients 2203 and 1674. miRNA, microRNA.

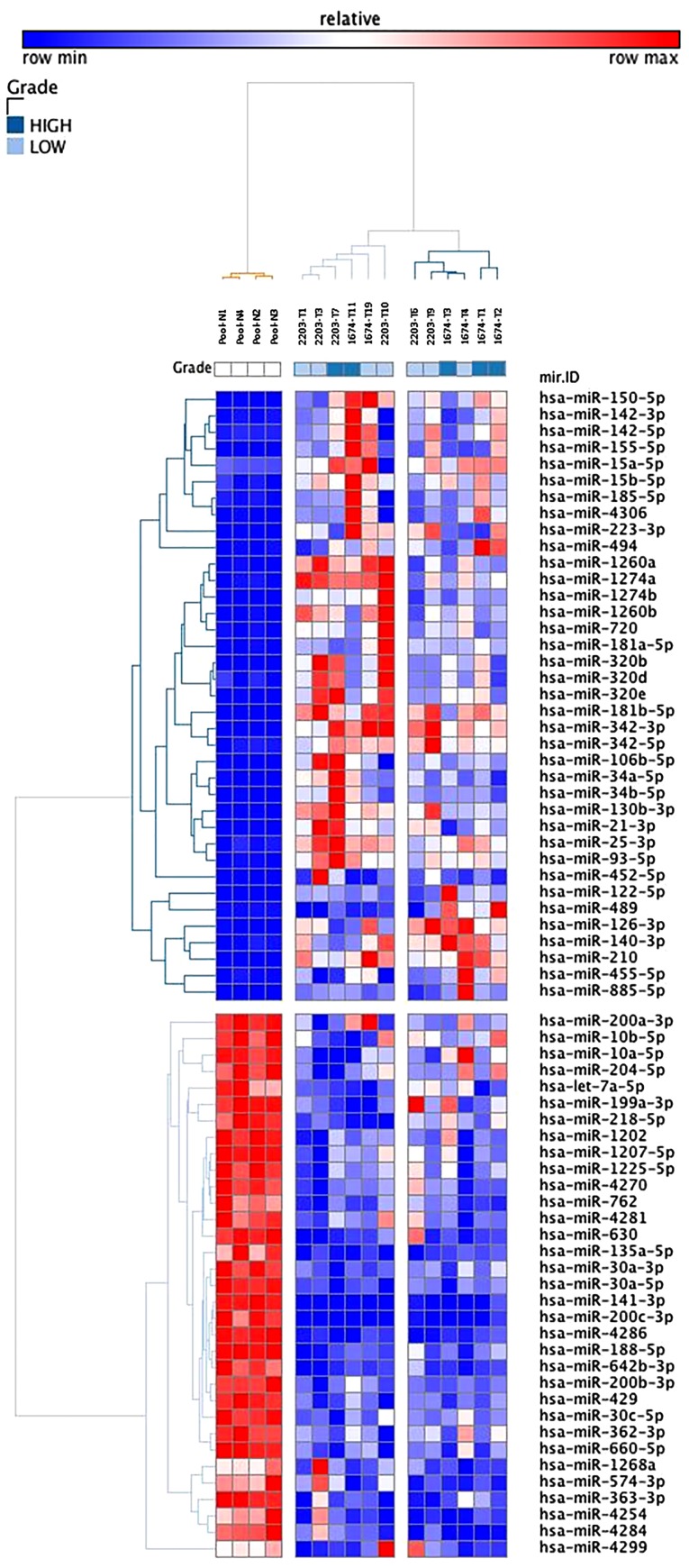

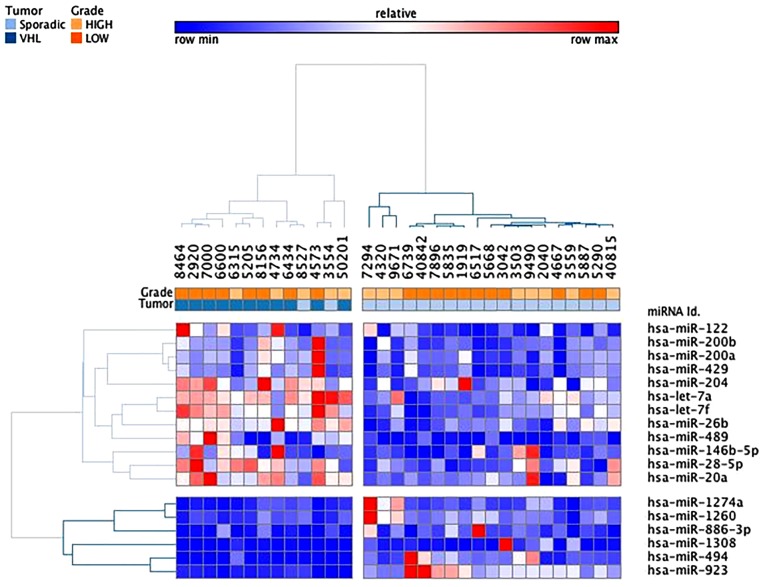

The present study also explored the differences between tumor samples and the normal reference samples, for each patient. For patient 2203, a total of 1,377 genes and 51 miRNAs were significantly differentially expressed. For patient 1674, a total of 1,282 genes and 56 miRNAs were differentially expressed (Table II). In addition, as shown in Fig. 2, a hierarchical cluster analysis built with 70 dysregulated miRNAs clearly indicated separate tumor clusters from the normal reference group. No obvious differences were detected between the samples, but the two subclusters could be distinguished according to the nuclear grade of these tumors. When tumors were compared two by two, no significant difference was found, thus supporting the hypothesis of a similar molecular evolution between independent tumors. KEGG biological pathway analysis was conducted using DAVID software. This analysis globally identified three classes of pathways that were overrepresented with dysregulated genes. Notably, in the two patients, the most significant pathways were similar, and were implicated in 'immunity' and 'metabolism' (Table III).

Table II.

Dysregulated miRNAs in patients 2203 and 1674.

| miRNA ID | Patient 2203 vs. normal pool

|

Patient 1674 vs. normal pool

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold-change | P-value | adj-P-value | Fold-change | P-value | adj-P-value | |

| Common miRNAs | ||||||

| Upregulated | ||||||

| hsa-miR-210 | 13.694 | 4.119×10−09 | 1.110×10−06 | 18.204 | 1.344×10−09 | 9.051×10−07 |

| hsa-miR-155-5p | 6.695 | 7.973×10−06 | 4.130×10−04 | 7.965 | 2.615×10−04 | 2.887×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-342-3p | 3.389 | 1.927×10−06 | 1.527×10−04 | 3.132 | 1.483×10−07 | 1.537×10−05 |

| hsa-miR-34a-5p | 3.373 | 2.187×10−04 | 3.983×10−03 | 2.519 | 7.045×10−04 | 5.858×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-1274a | 2.853 | 1.377×10−04 | 2.995×10−03 | 2.441 | 3.774×10−05 | 7.159×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-720 | 2.773 | 9.353×10−05 | 2.348×10−03 | 2.265 | 9.233×10−05 | 1.353×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-122-5p | 2.696 | 9.032×10−06 | 4.345×10−04 | 3.808 | 4.595×10−05 | 8.253×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-150-5p | 2.645 | 1.554×10−04 | 3.271×10−03 | 3.333 | 7.686×10−05 | 1.204×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-1274b | 2.531 | 6.167×10−04 | 7.416×10−03 | 2.235 | 1.829×10−05 | 4.663×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-34b-5p | 2.472 | 1.131×10−03 | 1.199×10−02 | 2.239 | 7.917×10−05 | 1.226×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-106b-5p | 2.463 | 8.830×10−03 | 4.815×10−02 | 2.191 | 1.354×10−06 | 7.601×10−05 |

| hsa-miR-25-3p | 2.361 | 5.440×10−05 | 1.629×10−03 | 2.343 | 3.438×10−07 | 2.724×10−05 |

| hsa-miR-93-5p | 2.342 | 3.627×10−05 | 1.164×10−03 | 2.209 | 1.910×10−07 | 1.838×10−05 |

| hsa-miR-885-5p | 2.059 | 7.217×10−05 | 1.984×10−03 | 2.749 | 4.733×10−04 | 4.438×10−03 |

| Downregulated | ||||||

| hsa-miR-762 | −2.148 | 6.373×10−04 | 7.597×10−03 | −2.456 | 3.143×10−06 | 1.520×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-4270 | −2.167 | 1.655×10−03 | 1.538×10−02 | −2.318 | 7.754×10−06 | 2.611×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-218-5p | −2.259 | 1.106×10−04 | 2.701×10−03 | −2.030 | 3.164×10−03 | 1.661×10−02 |

| hsa-miR-30a-3p | −2.371 | 3.591×10−05 | 1.164×10−03 | −2.185 | 6.318×10−05 | 1.051×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-1207-5p | −2.380 | 2.682×10−03 | 2.101×10−02 | −2.425 | 7.777×10−04 | 6.349×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-199a-3p | −2.382 | 5.068×10−03 | 3.354×10−02 | −3.405 | 6.913×10−03 | 3.053×10−02 |

| hsa-miR-188-5p | −2.474 | 3.029×10−05 | 1.046×10−03 | −2.172 | 3.194×10−06 | 1.520×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-30c-5p | −2.477 | 2.188×10−04 | 3.983×10−03 | −2.108 | 3.468×10−05 | 6.970×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-1225-5p | −2.485 | 3.166×10−03 | 2.331×10−02 | −2.403 | 7.302×10−04 | 6.034×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-4286 | −2.487 | 1.325×10−09 | 7.936×10−07 | −2.279 | 6.848×10−08 | 1.004×10−05 |

| hsa-miR-30a-5p | −2.490 | 8.286×10−06 | 4.134×10−04 | −2.253 | 5.463×10−06 | 2.230×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-4284 | −2.718 | 3.360×10−03 | 2.446×10−02 | −4.295 | 7.493×10−06 | 2.611×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-660-5p | −2.813 | 4.062×10−05 | 1.244×10−03 | −2.239 | 4.978×10−04 | 4.530×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-642b-3p | −2.863 | 3.629×10−05 | 1.164×10−03 | −2.775 | 4.850×10−08 | 1.004×10−05 |

| hsa-miR-135a-5p | −2.965 | 1.202×10−06 | 1.233×10−04 | −2.413 | 3.352×10−06 | 1.520×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-630 | −3.208 | 2.354×10−03 | 1.880×10−02 | −3.347 | 3.092×10−08 | 8.330×10−06 |

| hsa-miR-363-3p | −3.319 | 2.369×10−04 | 4.200×10−03 | −2.378 | 1.989×10−05 | 4.871×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-200b-3p | −3.577 | 5.841×10−05 | 1.684×10−03 | −2.609 | 2.844×10−05 | 5.918×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-429 | −3.657 | 1.300×10−04 | 2.917×10−03 | −2.893 | 2.199×10−05 | 5.197×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-1202 | −3.772 | 6.780×10−04 | 7.613×10−03 | −2.993 | 1.971×10−03 | 1.149×10−02 |

| hsa-miR-141-3p | −9.901 | 1.767×10−09 | 7.936×10−07 | −9.272 | 9.951×10−07 | 5.828×10−05 |

| hsa-miR-200c-3p | −12.485 | 3.817×10−09 | 1.110×10−06 | −11.832 | 9.017×10−07 | 5.784×10−05 |

| Specific miRNAs of patient 2203 | ||||||

| Upregulated | ||||||

| hsa-miR-21-3p | 2.705 | 1.544×10−05 | 6.710×10−04 | 1.845 | 1.092×10−03 | 7.619×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-1260b | 2.461 | 2.786×10−04 | 4.750×10−03 | 1.968 | 1.898×10−04 | 2.265×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-320d | 2.359 | 1.634×10−04 | 1.538×10−02 | 1.756 | 3.132×10−03 | 1.654×10−02 |

| hsa-miR-181b-5p | 2.339 | 4.412×10−08 | 9.083×10−06 | 1.983 | 3.519×10−05 | 6.970×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-1260a | 2.261 | 6.489×10−04 | 7.613×10−03 | 1.922 | 8.246×10−04 | 6.573×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-452-5p | 2.245 | 4.431×10−03 | 3.045×10−02 | 1.382 | 1.265×10−02 | 4.801×10−02 |

| hsa-miR-130b-3p | 2.243 | 1.656×10−06 | 1.394×10−04 | 1.742 | 2.452×10−06 | 1.270×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-320e | 2.178 | 5.735×10−04 | 7.087×10−03 | 1.837 | 2.525×10−05 | 5.755×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-320b | 2.168 | 7.956×10−04 | 8.856×10−03 | 1.714 | 2.918×10−04 | 3.144×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-342-5p | 2.129 | 1.601×10−05 | 6.741×10−04 | 1.971 | 1.339×10−07 | 1.503×10−05 |

| hsa-miR-223-3p | 2.056 | 2.665×10−04 | 4.602×10−03 | 1.867 | 9.326×10−03 | 3.830×10−02 |

| hsa-miR-181a-5p | 2.019 | 9.307×10−04 | 1.011×10−02 | 1.932 | 1.444×10−05 | 4.052×10−04 |

| Downregulated | ||||||

| hsa-miR-362-3p | −2.317 | 5.680×10−04 | 7.087×10−03 | −1.826 | 2.457×10−03 | 1.385×10−02 |

| hsa-miR-200a-3p | −2.552 | 1.657×10−04 | 3.433×10−03 | −1.575 | 3.224×10−02 | ns |

| hsa-miR-10a-5p | −3.326 | 4.392×10−04 | 5.915×10−03 | −1.965 | 4.617×10−02 | ns |

| Specific miRNAs of patient 1674 | ||||||

| Upregulated | ||||||

| hsa-miR-142-3p | 2.941 | 2.613×10−02 | ns | 4.372 | 1.588×10−03 | 9.811×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-489 | 1.231 | ns | ns | 3.434 | 1.139×10−02 | 4.447×10−02 |

| hsa-miR-142-5p | 2.116 | ns | ns | 3.205 | 1.006×10−03 | 7.348×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-494 | 1.975 | 1.863×10−03 | 1.647×10−02 | 2.621 | 1.116×10−03 | 7.709×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-126-3p | 1.940 | 1.606×10−03 | 1.538×10−02 | 2.191 | 1.047×10−04 | 1.454×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-15a-5p | 1.569 | ns | ns | 2.187 | 1.493×10−05 | 4.103×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-15b-5p | 1.045 | 1.237×10−02 | ns | 2.181 | 1.112×10−03 | 1.488×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-455-5p | 1.230 | ns | ns | 2.096 | 4.226×10−05 | 7.798×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-140-3p | 1.840 | 5.298×10−04 | 6.796×10−03 | 2.032 | 1.710×10−04 | 2.105×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-4306 | 1.368 | 3.099×10−03 | 2.306×10−02 | 2.005 | 3.613×10−04 | 3.632×10−03 |

| hsa-miR-185-5p | 1.387 | 2.402×10−02 | ns | 2.005 | 9.862×10−04 | 7.339×10−03 |

| Downregulated | ||||||

| hsa-miR-4299 | −1.489 | ns | ns | −2.035 | 1.415×10−05 | 4.052×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-4254 | −1.879 | 3.745×10−03 | 2.660×10−02 | −2.081 | 3.636×10−06 | 1.531×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-204-5p | −5.917 | 2.029×10−02 | ns | −2.12 | 8.344×10−03 | 3.491×10−02 |

| hsa-miR-1268a | −1.486 | ns | ns | −2.264 | 1.260×10−05 | 3.689×10−04 |

| hsa-miR-574-3p | −1.526 | 3.078×10−02 | ns | −2.314 | 9.952×10−07 | 5.828×10−05 |

| hsa-miR-10b-5p | −1.881 | 1.377×10−02 | ns | −2.338 | 8.231×10−03 | 3.463×10−02 |

| hsa-let-7a-5p | −1.933 | 1.263×10−03 | 1.288×10−02 | −2.377 | 1.679×10−03 | 1.014×10−02 |

| hsa-miR-4281 | −1.917 | 7.692×10−03 | 4.525×10−02 | −2.529 | 8.819×10−05 | 1.320×10−03 |

miR, microRNA; ns, not significant.

Figure 2.

miRNA expression profiles between multiple tumors from the same patients with von-Hippel Lindau disease. Two-dimensional hierarchical clustering (one-minus Pearson uncentered, average linkage) of the combined subsets of common dysregulated miRNAs in multiple tumors from the same patient compared with normal renal tissue (70 dysregulated miRNAs). miRNA, microRNA.

Table III.

Summary of major implicated pathways in VHL-associated and sporadic renal tumors.

| KEGG ID | KEGG description | KEGG subclass | KEGG class |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common pathways in both tumor groups | |||

| hsa04115 | p53 signaling pathway | Cell growth and death | Cellular processes |

| hsa04510 | Focal adhesion | Cellular community | |

| hsa04540 | Gap junction | ||

| hsa04060 | Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | Signaling molecules and interaction | Environmental information processing |

| hsa04514 | Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) | ||

| hsa04512 | ECM-receptor interaction | ||

| hsa05200 | Pathways in cancer | Cancers: Overview | Human diseases |

| hsa03320 | PPAR signaling pathway | Endocrine system | Organismal systems |

| hsa04960 | Aldosterone-regulated sodium reabsorption | Excretory system | |

| hsa04610 | Complement and coagulation cascades | Immune system | |

| hsa04650 | Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | ||

| hsa04640 | Hematopoietic cell lineage | ||

| hsa04672 | Intestinal immune network for IgA production | ||

| hsa04610 | Complement and coagulation cascades | ||

| hsa04062 | Chemokine signaling pathway | ||

| hsa04612 | Antigen processing and presentation | ||

| hsa04621 | NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | ||

| hsa04660 | T cell receptor signaling pathway | ||

| hsa04670 | Leukocyte transendothelial migration | ||

| hsa00532 | Chondroitin sulfate biosynthesis | Glycan biosynthesis and metabolism | Metabolism |

| hsa00280 | Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation | Amino acid metabolism | |

| hsa00380 | Tryptophan metabolism | ||

| hsa00330 | Arginine and proline metabolism | ||

| hsa00260 | Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | ||

| hsa00250 | Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism | ||

| hsa00340 | Histidine metabolism | ||

| hsa00310 | Lysine degradation | ||

| hsa00270 | Cysteine and methionine metabolism | ||

| hsa00350 | Tyrosine metabolism | ||

| hsa00640 | Propanoate metabolism | Carbohydrate metabolism | |

| hsa00650 | Butanoate metabolism | ||

| hsa00620 | Pyruvate metabolism | ||

| hsa00020 | Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | ||

| hsa00053 | Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism | ||

| hsa00010 | Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | ||

| hsa00040 | Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | ||

| hsa00500 | Starch and sucrose metabolism | ||

| hsa00630 | Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | ||

| hsa00190 | Oxidative phosphorylation | Energy metabolism | |

| hsa00910 | Nitrogen metabolism | ||

| hsa00071 | Fatty acid metabolism | Global and overview maps | |

| hsa00072 | Synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies | Lipid metabolism | |

| hsa00140 | Steroid hormone biosynthesis | ||

| hsa00120 | Primary bile acid biosynthesis | ||

| hsa00590 | Arachidonic acid metabolism | ||

| hsa00062 | Fatty acid elongation in mitochondria | ||

| hsa00830 | Retinol metabolism | Metabolism of cofactors and vitamins | |

| hsa00410 | β-Alanine metabolism | Metabolism of other amino acids | |

| hsa00480 | Glutathione metabolism | ||

| hsa00903 | Limonene and pinene degradation | Metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides | |

| hsa00982 | Drug metabolism-cytochrome P450 | Xenobiotics biodegradation and metabolism | |

| hsa00980 | Metabolism of xenobiotics | ||

| by cytochrome P450 | |||

| hsa00983 | Drug metabolism-other enzymes | ||

| Specific to VHL-associated tumors | |||

| hsa04330 | Notch signaling pathway | Signal transduction | Environmental information processing |

| hsa00900 | Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis | Metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides | Metabolism |

| Specific to sporadic tumors | |||

| hsa04110 | Cell cycle | Cell growth and death | Cellular processes |

| hsa04630 | Jak-STAT signaling pathway | Signal transduction | Environmental information processing |

| hsa04666 | FcγR-mediated phagocytosis | Immune system | Organismal systems |

| hsa04662 | B cell receptor signaling pathway | ||

| hsa04620 | Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | ||

| hsa01040 | Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | Lipid metabolism | Metabolism |

| hsa00100 | Steroid biosynthesis | ||

| hsa00360 | Phenylalanine metabolism | Amino acid metabolism |

VHL, von Hippel-Lindau.

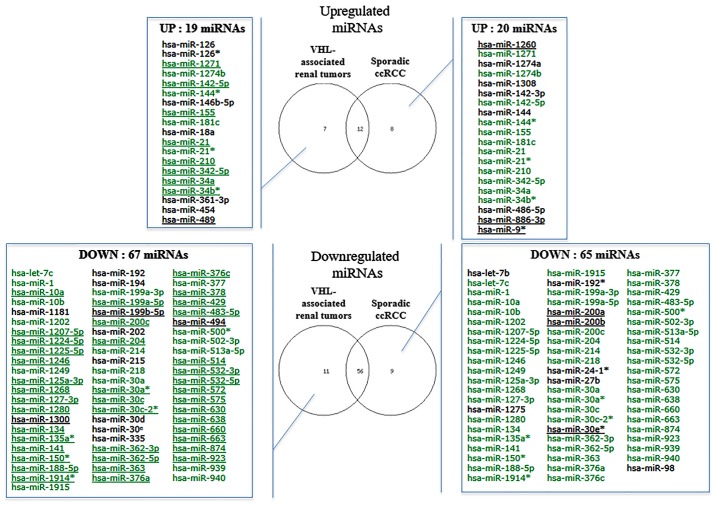

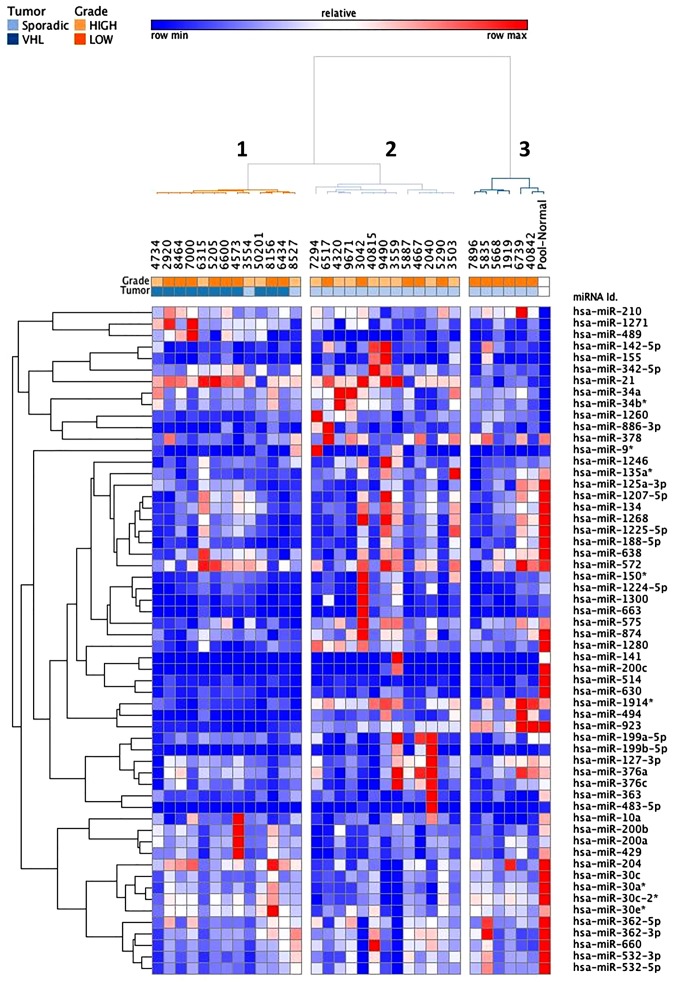

miRNA expression levels distinguish VHL-associated tumors from sporadic ccRCC

Using microarray analysis, a total of 103 miRNAs were identified as differentially expressed among the VHL-associated and sporadic ccRCC samples (fold-change <−2 or >2) compared with in the normal reference group (Fig. 3). These differentially expressed miRNAs are similar to those described in the first set of samples. Two thirds of miRNAs (12 upregulated and 56 downregulated) were common to both groups. Hierarchical cluster analysis, based on the 58 most differentially expressed miRNAs (fold-change <-3 or >3), revealed three clusters that mainly define VHL-associated (cluster 1) and sporadic (clusters 2 and 3) specimen profiles (Fig. 4). Of the 21 sporadic ccRCC samples, only two samples were allocated to the VHL-related branch. Branches 2 and 3 were able to distinguish high and low grades of sporadic ccRCC, respectively. The VHL-associated tumors formed a separate subcluster (cluster 1), thus indicating that their miRNA expression levels were different from those of sporadic tumor samples. In addition, supervised analysis directly comparing the VHL-associated and sporadic tumors (fold-change <−1.5 or >1.5; raw P<0.05) identified 18 differentially expressed miRNAs (Table IV and Fig. 5). Taken together, these analyses indicated that, even though some differentially expressed miRNAs were similar between the two tumor groups, it was possible to distinguish between these two groups.

Figure 3.

Lists of dysregulated miRNAs in VHL-associated renal tumors and sporadic ccRCC tumors compared with in the normal renal pool (fold-change <−2 or >2). Underlined miRNAs refer to miRNAs with a fold-change <−3 or >3. miRNAs in green refer to common dysregulated miRNAs in both groups. ccRCC, clear-cell renal cell carcinoma; miRNA, microRNA; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional hierarchical clustering (Pearson uncentered, average linkage) of the combined subsets of common dysregulated miRNAs in VHL-associated and sporadic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma compared with in normal renal tissue (58 dysregulated miRNAs with fold-change <−3 or >3). Upregulation is shown in red, whereas downregulation is indicated in blue. miRNA, microRNA; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau.

Table IV.

Dysregulated miRNAs between VHL-associated and sporadic ccRCC samples.

| miRNA ID | Fold-change (VHL/sporadic) | Raw P-value | adj-P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated miRNAs | |||

| hsa-miR-489 | 2.267 | 0.0103 | ns |

| hsa-miR-204 | 2.266 | 0.0078 | ns |

| hsa-let-7f | 1.946 | 0.0004 | 0.0123 |

| hsa-miR-200b | 1.914 | 0.0012 | 0.0216 |

| hsa-let-7a | 1.821 | 5.8836×10−05 | 0.0036 |

| hsa-miR-200a | 1.767 | 0.0035 | 0.0454 |

| hsa-miR-146b-5p | 1.684 | 0.0283 | ns |

| hsa-miR-429 | 1.611 | 0.0066 | ns |

| hsa-miR-26b | 1.579 | 0.0004 | 0.0121 |

| hsa-miR-28-5p | 1.542 | 0.0006 | 0.0121 |

| hsa-miR-122 | 1.527 | 0.0347 | ns |

| hsa-miR-20a | 1.521 | 0.0002 | 0.0092 |

| Downregulated miRNAs | |||

| hsa-miR-1274a | −1.580 | 0.0114 | ns |

| hsa-miR-1260 | −1.727 | 0.0027 | 0.0386 |

| hsa-miR-886-3p | −1.764 | 0.0399 | ns |

| hsa-miR-1308 | −1.812 | 0.0136 | ns |

| hsa-miR-494 | −2.882 | 6.0369×10−05 | 0.0036 |

| hsa-miR-923 | −4.149 | 2.0833×10−06 | 0.0006 |

miRNA, microRNA; ns, not significant; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau.

Figure 5.

Two-dimensional hierarchical clustering (Pearson uncentered, average linkage) of the dysregulated miRNAs in VHL-associated ccRCC compared with in sporadic ccRCC (18 dysregulated miRNAs with fold-change <−1.5 or >1.5 and raw P<0.05). Upregulation is shown in red, whereas downregulation is indicated in blue. miRNA, microRNA; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau.

Transcriptomic analyses identify biological pathways involved in VHL-associated tumors

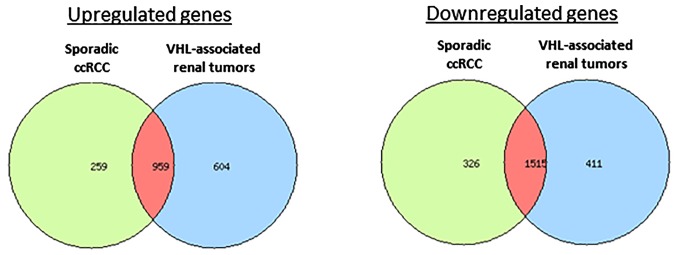

Transcriptomic analysis was performed to identify genes exhibiting altered expression in renal VHL-associated tumors. mRNA profiles from VHL-associated and sporadic ccRCC groups were compared with the normal renal tissue pool. Similar to the findings of the miRNA analysis, few differences in mRNA expression profiles were detected between the two series of ccRCC. Notably, 3,489 (1,563 up- and 1,926 downregulated) and 3,059 (1,218 up- and 1,841 downregulated) genes were dysregulated in VHL-related tumors and sporadic ccRCC, respectively, compared with in the normal renal tissue pool. A total of 2,474 genes (959 up- and 1515 downregulated) were found in common between the groups, representing 71 and 81% of each signature, respectively (Fig. 6). Dysregulated pathways were similar to those previously described for the first set of samples (Table III).

Figure 6.

Venn diagrams of dysregulated genes in VHL-associated renal tumors and sporadic ccRCC. ccRCC, clear-cell renal cell carcinoma; VHL, von-Hippel-Lindau.

Discussion

The present study detected differentially expressed mRNAs and miRNAs in VHL-associated ccRCC, in order to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of these hereditary tumors. The results of the miRNA and mRNA integrative analysis indicated that synchronous tumors occurring in the same organ in one individual, and developing from an identical germline background, are molecularly similar even if these renal tumors are of independent clonal origin. These results suggested that the final molecular evolution is not random, and confirmed the 'contingency and convergency' hypothesis previously described by Fisher et al (10). Therefore, it may be hypothesized that VHL-associated tumors harbor the same expression pattern due to loss of the VHL gene; however, the difference in global genetic background between the two patients used in the present study allows for the distinction between the different samples of these patients.

The present study demonstrated that miRNA and mRNA expression levels may be used to distinguish VHL-associated renal tumors from sporadic ccRCC. The sporadic ccRCC miRNA signature was similar to ones previously described (14,19,20). The identified miRNAs were also able to distinguish between high-grade and low-grade ccRCC, as previously reported (21).

In the present study, miR-210 was markedly overexpressed in VHL-associated and sporadic tumors. Overexpression of miR-210 has previously been described in sporadic ccRCC and in several hypoxic tumors (22–24); therefore, its overexpression in VHL-associated RCC is not surprising due to its pseudohypoxic gene signature (25). miR-210 modulates the cellular hypoxic response via a wide range of actions. In particular, miRNA and mRNA profiles of renal VHL-associated tumors are very similar to hypoxic signatures previously reported (26). Another pro-oncogenic pathway was identified through miR-155, which promotes the growth of tumors by targeting VHL mRNA (27,28) and the activity of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1) during prolonged hypoxia (29). Other miRNAs identified in the present study have also been described in the literature, including miR-28-5p, which promotes chromosomal instability in ccRCC by inhibiting mitotic arrest deficient 2 translation (30), or miR-30c-3p (previous ID: miR-30c-2*) and miR-30a-3p, which inhibit HIF2 activity in ccRCC (31).

An altered metabolic pattern has previously been identified in ccRCC studies (32,33). VHL, MET proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase, folliculin, TSC complex subunit 1 (TSC1), TSC2, fumarate hydratase and succinate dehydrogenase are known as renal cancer-predisposing genes, which are all involved in pathways that respond to metabolic stress or nutrient stimulation. It has previously been suggested that RCC may be regarded as a metabolic disease (34). It may be interesting to perform a metabolic analysis to assess metabolic alterations in ccRCC. It is possible that dysregulated metabolism is fundamental for the occurrence of ccRCC and may provide the basis for the development of novel forms of therapy. In addition, the present study identified numerous upregulated pathways that were associated with the immune system. ccRCC has previously been demonstrated to be immunogenic. Notably, a number of immune cells have been isolated from ccRCC, including natural killer cells, cytotoxic T cells, helper T cells and dendritic cells (35–38). When ccRCC appears as an antigen in the human body, immune activity is induced, leading to a series of enhanced immunization activities. Several genes implicated in these pathways were regulated by the VHL/HIF pathway, including C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 and stromal cell-derived factor-1α (39). Further studies, in order to obtain an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms implicating the VHL gene may be beneficial for the development of novel treatments.

Within the genome, clustering of miRNA genes is common, with 38% of known miRNA genes residing in clusters (40). The present profiling data revealed dysregulation of several miRNA clusters, notably the δ-like non-canonical Notch ligand 1-maternally expressed 3 miRNA cluster (on chromosome 14q32) in all ccRCC samples. Evolutionary conservation of clustered miRNA genes suggests an important common biological function, co-regulating identical targets or components in the same pathway (41). Notably, several miRNAs mapping to 14q32 have been predicted to regulate the same target genes. Loss of expression of this miRNA cluster or other genes in close proximity has previously been reported in ccRCC (42), as well as in other types of cancer (43–45). For example, in osteosarcoma, down-regulation of 14q32 miRNAs stabilizes c-MYC, facilitates apoptotic escape, and sustains tumorigenesis (43). In addition, the MYC pathway is activated in ccRCC and essential for proliferation of ccRCC cells (46). These findings suggested that loss of expression of miRNAs clustered at 14q32 further dysregulates the MYC network and likely contributes to ccRCC development. The 14q32 miRNA cluster members, miR-134 and miR-494, were generally downregulated in nearly all tumors and are described as tumor suppressors in ccRCC cells. miR-134 downregulates cell proliferation and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by targeting KRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase (47). A miRNA regulatory balance of oncogenic, metabolic and immune pathways must be struck in ccRCC tumor cells to permit tumor progression. Functional assays and global proteomic analysis are required to better characterize these interaction networks.

In conclusion, from various clonal tumors within the kidney of the same patient, a functional convergence on hypoxic, immune response and metabolism pathways was evidenced, thus contributing to the synchronous oncogenesis of these tumors. Several miRNAs significantly differentially expressed between VHL-related renal tumors and sporadic ccRCC were identified through global miRNA expression profiling, thus suggesting a role for these miRNAs in these tumors. Although further cellular and histological studies are required to determine the precise roles played by these miRNA-mRNA pathways in VHL-associated ccRCC, the present results may help provide a better understanding of these hereditary tumors.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the present study would like to thank Dr Vladimir Lazar and Mrs Véronique Roux (Genomic Platform, Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France) for helping to design the micro-array experiments. The authors are also grateful to Centre de Ressources Biologiques from Necker and Saint Joseph Hospitals (Paris, France) and Bicêtre Hospital (Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France) for the frozen samples used to perform the present study.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the 'Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer' (Comités du Cher et de l'Indre), the French National Cancer Institute (INCa, PNES Kidney Cancer), the 'Association VHL France' and by 'Taxes d'Apprentissage Gustave Roussy' (P18_SG, P20_VPT et P24_MACH).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

Authors' contributions

CHG participated in the design of the study, analyzed the data, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. CO and ND performed the microarray experiments. GM and PD performed the microarray analyses. MC helped to analyze the data. AM, SGi and SR recruited the patients, conducted follow-up appointments and obtained their consent for the study. SF, VVe, VVa and VM collected ccRCC tissues stored in official structures at Bicêtre, Necker and St Joseph hospitals. SC, BG, BB, BTT and SR helped to analyze and interpret the data, and critically revised the manuscript. SGa conceived the study, and participated in its design and coordination, supervised the experiments, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the ethical committee of Bicêtre Hospital (Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France). All patients provided written informed consent prior to surgery for the use of their tumors.

Consent for publication

All patients had provided written informed consent prior to surgery.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Richard S, Gardie B, Couvé S, Gad S. Von Hippel-Lindau: How a rare disease illuminates cancer biology. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuhrman SA, Lasky LC, Limas C. Prognostic significance of morphologic parameters in renal cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6:655–663. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato Y, Yoshizato T, Shiraishi Y, Maekawa S, Okuno Y, Kamura T, Shimamura T, Sato-Otsubo A, Nagae G, Suzuki H, et al. Integrated molecular analysis of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:860–867. doi: 10.1038/ng.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu P, Liu JL, Pei SM, Wu CP, Yang K, Wang SP, Wu S. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of renal clear cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:287. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4176-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiesen HJ, Steinbeck F, Maruschke M, Koczan D, Ziems B, Hakenberg OW. Stratification of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) genomes by gene-directed copy number alteration (CNA) analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerlinger M, Horswell S, Larkin J, Rowan AJ, Salm MP, Varela I, Fisher R, McGranahan N, Matthews N, Santos CR, et al. Genomic architecture and evolution of clear cell renal cell carcinomas defined by multiregion sequencing. Nat Genet. 2014;46:225–233. doi: 10.1038/ng.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Genome Atlas, Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beroukhim R, Brunet JP, Di Napoli A, Mertz KD, Seeley A, Pires MM, Linhart D, Worrell RA, Moch H, Rubin MA, et al. Patterns of gene expression and copy-number alterations in von-hippel lindau disease-associated and sporadic clear cell carcinoma of the kidney. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4674–4681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shuib S, Wei W, Sur H, Morris MR, McMullan D, Rattenberry E, Meyer E, Maxwell PH, Kishida T, Yao M, et al. Copy number profiling in von Hippel-Lindau disease renal cell carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50:479–488. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher R, Horswell S, Rowan A, Salm MP, de Bruin EC, Gulati S, McGranahan N, Stares M, Gerlinger M, Varela I, et al. Development of synchronous VHL syndrome tumors reveals contingencies and constraints to tumor evolution. Genome Biol. 2014;15:433. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0433-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iorio MV, Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation. Cancer J. 2012;18:215–222. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318250c001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juan D, Alexe G, Antes T, Liu H, Madabhushi A, Delisi C, Ganesan S, Bhanot G, Liou LS. Identification of a microRNA panel for clear-cell kidney cancer. Urology. 2010;75:835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neal CS, Michael MZ, Rawlings LH, Van der Hoek MB, Gleadle JM. The VHL-dependent regulation of microRNAs in renal cancer. BMC Med. 2010;8:64. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Messai Y, Gad S, Noman MZ, Le Teuff G, Couve S, Janji B, Kammerer SF, Rioux-Leclerc N, Hasmim M, Ferlicot S, et al. Renal cell carcinoma programmed death-ligand 1, a new direct target of hypoxia-inducible factor-2 alpha, is regulated by von Hippel-Lindau gene mutation status. Eur Urol. 2016;70:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, et al. Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva-Santos RM, Costa-Pinheiro P, Luis A, Antunes L, Lobo F, Oliveira J, Henrique R, Jerónimo C. MicroRNA profile: A promising ancillary tool for accurate renal cell tumour diagnosis. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2646–2653. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christinat Y, Krek W. Integrated genomic analysis identifies subclasses and prognosis signatures of kidney cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:10521–10531. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gowrishankar B, Ibragimova I, Zhou Y, Slifker MJ, Devarajan K, Al-Saleem T, Uzzo RG, Cairns P. MicroRNA expression signatures of stage, grade, and progression in clear cell RCC. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:329–341. doi: 10.4161/cbt.27314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miko E, Czimmerer Z, Csánky E, Boros G, Buslig J, Dezso B, Scholtz B. Differentially expressed microRNAs in small cell lung cancer. Exp Lung Res. 2009;35:646–664. doi: 10.3109/01902140902822312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan SY, Loscalzo J. MicroRNA-210: A unique and pleiotropic hypoxamir. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1072–1083. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.6.11006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puisségur MP, Mazure NM, Bertero T, Pradelli L, Grosso S, Robbe-Sermesant K, Maurin T, Lebrigand K, Cardinaud B, Hofman V, et al. miR-210 is overexpressed in late stages of lung cancer and mediates mitochondrial alterations associated with modulation of HIF-1 activity. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:465–478. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Couvé S, Ladroue C, Laine E, Mahtouk K, Guégan J, Gad S, Le Jeune H, Le Gentil M, Nuel G, Kim WY, et al. Genetic evidence of a precisely tuned dysregulation in the hypoxia signaling pathway during oncogenesis. Cancer Res. 2014;74:6554–6564. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulshreshtha R, Davuluri RV, Calin GA, Ivan M. A microRNA component of the hypoxic response. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:667–671. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen D, Cabay RJ, Jin Y, Wang A, Lu Y, Shah-Khan M, Zhou X. MicroRNA deregulations in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2013;4:e2. doi: 10.5037/jomr.2013.4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong W, He L, Richards EJ, Challa S, Xu CX, Permuth-Wey J, Lancaster JM, Coppola D, Sellers TA, Djeu JY, et al. Upregulation of miRNA-155 promotes tumour angiogenesis by targeting VHL and is associated with poor prognosis and triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33:679–689. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruning U, Cerone L, Neufeld Z, Fitzpatrick SF, Cheong A, Scholz CC, Simpson DA, Leonard MO, Tambuwala MM, Cummins EP, et al. MicroRNA-155 promotes resolution of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha activity during prolonged hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4087–4096. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01276-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hell MP, Thoma CR, Fankhauser N, Christinat Y, Weber TC, Krek W. miR-28-5p promotes chromosomal instability in VHL-associated cancers by inhibiting Mad2 translation. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2432–2443. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathew LK, Lee SS, Skuli N, Rao S, Keith B, Nathanson KL, Lal P, Simon MC. Restricted expression of miR-30c-2-3p and miR-30a-3p in clear cell renal cell carcinomas enhances HIF2α activity. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:53–60. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Favier J, Brière JJ, Burnichon N, Rivière J, Vescovo L, Benit P, Giscos-Douriez I, De Reyniès A, Bertherat J, Badoual C, et al. The Warburg effect is genetically determined in inherited pheochromocytomas. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullen AR, Wheaton WW, Jin ES, Chen PH, Sullivan LB, Cheng T, Yang Y, Linehan WM, Chandel NS, DeBerardinis RJ. Reductive carboxylation supports growth in tumour cells with defective mitochondria. Nature. 2011;481:385–388. doi: 10.1038/nature10642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Genetic predisposition to kidney cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:566–574. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elsässer-Beile U, Grussenmeyer T, Gierschner D, Schmoll B, Schultze-Seemann W, Wetterauer U, Schulte Mönting J. Semiquantitative analysis of Th1 and Th2 cytokine expression in CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ renal-cell-carcinoma-infiltrating lymphocytes. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1999;48:204–208. doi: 10.1007/s002620050566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finke JH, Rayman P, Edinger M, Tubbs RR, Stanley J, Klein E, Bukowski R. Characterization of a human renal cell carcinoma specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cell line. J Immunother. 1992;1991(11):1–11. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaudin C, Dietrich PY, Robache S, Guillard M, Escudier B, Lacombe MJ, Kumar A, Triebel F, Caignard A. In vivo local expansion of clonal T cell subpopulations in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1995;55:685–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwaab T, Schned AR, Heaney JA, Cole BF, Atzpodien J, Wittke F, Ernstoff MS. In vivo description of dendritic cells in human renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1999;162:567–573. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zagzag D, Krishnamachary B, Yee H, Okuyama H, Chiriboga L, Ali MA, Melamed J, Semenza GL. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha and CXCR4 expression in hemangioblastoma and clear cell-renal cell carcinoma: Von Hippel-Lindau loss-of-function induces expression of a ligand and its receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6178–6188. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altuvia Y, Landgraf P, Lithwick G, Elefant N, Pfeffer S, Aravin A, Brownstein MJ, Tuschl T, Margalit H. Clustering and conservation patterns of human microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2697–2706. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan X, Liu C, Yang P, He S, Liao Q, Kang S, Zhao Y. Clustered microRNAs' coordination in regulating protein-protein interaction network. BMC Syst Biol. 2009;3:65. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawakami T, Chano T, Minami K, Okabe H, Okada Y, Okamoto K. Imprinted DLK1 is a putative tumor suppressor gene and inactivated by epimutation at the region upstream of GTL2 in human renal cell carcinoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:821–830. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thayanithy V, Sarver AL, Kartha RV, Li L, Angstadt AY, Breen M, Steer CJ, Modiano JF, Subramanian S. Perturbation of 14q32 miRNAs-cMYC gene network in osteosarcoma. Bone. 2012;50:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gattolliat CH, Thomas L, Ciafrè SA, Meurice G, Le Teuff G, Job B, Richon C, Combaret V, Dessen P, Valteau-Couanet D, et al. Expression of miR-487b and miR-410 encoded by 14q32.31 locus is a prognostic marker in neuroblastoma. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1352–1361. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gattolliat CH, Le Teuff G, Combaret V, Mussard E, Valteau-Couanet D, Busson P, Bénard J, Douc-Rasy S. Expression of two parental imprinted miRNAs improves the risk stratification of neuroblastoma patients. Cancer Med. 2014;3:998–1009. doi: 10.1002/cam4.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang SW, Chang WH, Su YC, Chen YC, Lai YH, Wu PT, Hsu CI, Lin WC, Lai MK, Lin JY. MYC pathway is activated in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and essential for proliferation of clear cell renal cell carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;273:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Y, Zhang M, Qian J, Bao M, Meng X, Zhang S, Zhang L, Zhao R, Li S, Cao Q, et al. miR-134 functions as a tumor suppressor in cell proliferation and epithelial-to-mesenchymal Transition by targeting KRAS in renal cell carcinoma cells. DNA Cell Biol. 2015;34:429–436. doi: 10.1089/dna.2014.2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on request.