Abstract

Pyrethrins are effective food-grade bio-pesticides obtained from the flowers of Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium and this crop cannot be cultivated widely in India due to its specific agro-climatic requirement. Hence pyrethrins are mostly imported from Kenya. Therefore, the present study aims to develop a process for augmentation of pyrethrin contents in C. cinerariaefolium callus and establish the correlation between early knockdown effects through docking on grain storage insect. In vitro seedlings were used as explants to induce callus on MS medium with different concentrations of auxins and cytokinins. Pyrethrin extracted from the callus was estimated by RP-HPLC. In callus, total pyrethrin was found to be 17.5 µg/g, which is higher than that found in natural flowers of certain Pyrethrum cultivars. The concentrations of cinerin II, pyrethrin II and jasmoline II were quite high in callus grown on solid medium. Bio-efficacy of pyrethrum extracts of flower and callus on insect Tribolium sp., showed higher repellency and early knock-down effect when compared with pure compound pestanal. Further, the rapid knockdown effect of all pyrethrins components was established by molecular docking studies targeting NavMS Sodium Channel Pore receptor docking followed by multiple ligands simultaneous docking, performed to investigate the concurrent binding of different combinations of pyrethrin. Among the six pyrethrin components, the pyrethrin I and II were found to be a more efficient, binding more firmly to the target, exhibiting higher possibilities of insecticidal effect by an early knockdown mechanism.

Keywords: Tribolium sp., C. cinerariaefolium, Sodium-gate receptor, Bio-pesticides, Molecular docking

Introduction

There has been a continuous exploration for bio-pesticides, which benefit humans and the environment. The market for effective bio-pesticides crosses a few thousand billion US dollars. Pyrethrins are currently the most economically important natural insecticides of plant origin (Hitmi et al. 2000) having importance for food grain storage and other domestic applications. The pyrethrins are the group of six structurally close monoterpene esters and are based on the type of monoterpenic acid molecule (chrysanthemic acid and pyrethric acid) in ester molecule; pyrethrins are classified into two groups, namely, pyrethrins I and pyrethrins II. Pyrethrin I, cinerin I, and jasmolin I together called Pyrethrins I and these are the group of monoterpene esters produced by esterification of chrysanthemic acid with ketone alcohols (pyrethrolone, cinerolone, and jasmolone). Similarly, Pyrethrins II are the of monoterpene esters produced by esterification of pyrethric acid with ketone alcohols (Jovetic and De Gooijer 1995; Hitmi et al. 2000). These compounds are natural insecticides, which are derived from the flower heads’ extracts of C. cinerariaefolium. Pyrethrin extracts are found to be effective for large groups of insects, viz., Lygus spp., Leptinotarsa decemnileata, Pieris rapae, Tribolium sp., Aspodydia spp., Empoasca devastans, Leucinodes orbonalis, Ophiomyia reticulata and numerous caterpillars, mites, mosquitoes, thrips, and moths (Van Latum and Gerrits 1991). Knockdown is a kind of paralysis initiated immediately within few minutes of treatment and followed by death after several hours. Immediate knockdown effect is due to the pyrethrin action on neuronal voltage-sensitive sodium channels. Pyrethroids are chemically synthesised and structurally analogue to naturally available pyrethrins. These are neurotoxic insecticides and have an impact on the nervous system, but a definite mechanism of their action is unknown (Davies et al. 2007). Among the many approaches to describe the mechanism of action of pyrethrins, the alterations (polarised membranes) in sodium channel dynamics in nerve cells leads to abnormal discharge in targeted neurons (Elias 2013). The repellency action is considered to be more significant than the insecticidal activity during food protection (Crombie 1980). Further, according to the reports of Environmental Protection Agency (1989) pyrethrins have least risk to mammals and human beings, which is unveiled by toxilogical tests (Shoenig 1995). However, pyrethrins rapidly lose their insecticidal activity due to the instability when exposed to air and light. This property makes pyrethrins widely acceptable as safe and environmentally innocuous alternatives to other “hard pesticides” (Allan and Miller 1990).

Pyrethrins have been identified in different species of the Asteraceae (ex Compositae) family: C. cinerariaefolium, C. coccinum, Calendula officinalis, Tagetes erecta, Tagetes minuta, Zinnia elegans, Zinia linnearis, etc. Even though economically important, the world supply cannot meet the growing market due to non-availability of high-quality seed-yielding plants adapted to various environments with high yields per hectare (Li et al. 2011). Since the Pyrethrum crop requires specific temperate agro-climatic conditions, all countries, especially certain tropical ones cannot produce this essential commodity; hence there is a huge international market for the production of natural pyrethrins. Some synthetic analogues of natural pyrethrins are currently being marketed, but such synthetic compounds are seldom without toxicity. Alternatively, tissue culture method is found to be a boon for the production of natural pyrethrins, and all the six compounds were recorded in the callus cultures (Fujii and Shimizu 1990). Further, Rajasekaran et al. (1991) also reported that the repellent and knock-down (KD) properties of pyrethrins obtained from 3-week-old leaf callus cultures of C. cinerariifolium and compared with naturally derived standards.

With the advances in computational techniques, new and robust techniques have been developed to simulate and study the molecular mechanisms of living systems (Ekins et al. 2007). This has led to the development of novel approaches in pharmaceutical hypothesis development and research, viz., computer-aided drug discovery, structure-based drug discovery and much more (Ferreira et al. 2015). By these techniques, it is also possible to interpret the novel target molecules in a specific disease condition and study the binding interactions of drugs with such targets (Ekins et al. 2007).

The literature review indicated that C. cinerariaefolium had been subjected to rigorous pyrethrins production using different tissue culture aspects. However, there is an essential need of a standardized protocol for the establishment of a callus capable of producing a high concentration of the pyrethrin. Literature survey also enlightens the lack of proper correlation between mechanisms of actions for the repellence/knockdown activity by pyrethrins in different insect models. Hence the current study reports about the standardization of protocol for the augmentation of pyrethrin content in the callus, while establishing the correlation between repellency/knockdown activity and the molecular mechanism of action of pyrethrin through the tracking of NavMS Sodium Channel Pore receptor.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Pestanal obtained from Sigma–Aldrich and commercially available pyrethrum extract (Nitapole, Industries, Kolkata) were used as reference standards. Acetonitrile HPLC grade and hexane analytical grade were obtained from MERCK. Millipore water was used for dilution and as the carrier solvent.

Tissue culture

The certified Pyrethrum seeds (C. cinereriaefolium) were obtained from the Jammu & Kashmir Medicinal Plants-JKMPIC, Introduction Centre India, and subjected to surface sterilisation using 1% mercuric chloride (W/V) for 15 min before inoculation onto MS media. The MS media was prepared with 100 mg/l of inositol and 30 g/l sucrose and pH of the medium was adjusted to 5.7. The culture vials with media were steam-sterilised in the autoclave at 15 lbs/in2 at a temperature of 121 °C for 20 min. The in vitro germinated seedlings were used to prepare explants, viz., shoot tip, hypocotyl, cotyledon and root as a source for callus induction and multiple shoot formations. All the explants were excised and inoculated aseptically onto the media fortified with different 2, 4 D (2, 4 Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) (0.5–3 mg/l) and Kin (Kinetin) (0.4 and 1.0 mg/l) for callus induction (Table 1) and for shoot induction benzyl adenine (BA) (2 mg/l) and Kin (0.2 mg/l) were used. Further, to enhance the callus proliferation and to increase in the pyrethrin contents, the media was supplemented with additional supplements like adenine sulphate, colchicine and coconut water alone or in combination.

Table 1.

Effect of 24-D and Kn concentration on the callus induction from C. cinerariaefolium

| Sl no | Plant growth regulators (in mg/L) | Callus response (in %) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2,4-D | Kn | ||

| 1. | 0.5 | 0.4 | 35.9 ± 1.722bc |

| 2. | 0.5 | 1.0 | 31.9 ± 1.242b |

| 3. | 1.0 | 0.4 | 52.4 ± 2.535d |

| 4. | 1.0 | 1.0 | 46.4 ± 1.667d |

| 5. | 1.5 | 0.4 | 70.2 ± 2.520f |

| 6. | 1.5 | 1.0 | 60.3 ± 2.736e |

| 7. | 2.0 | 0.4 | 99.9 ± 0.887i |

| 8. | 2.0 | 1.0 | 88.4 ± 0.871h |

| 9. | 2.5 | 0.4 | 78.4 ± 1.984 g |

| 10. | 2.5 | 1.0 | 70.7 ± 2.376f |

| 11. | 3.0 | 0.4 | 65.1 ± 1.516ef |

| 12. | 3.0 | 1.0 | 50.8 ± 1.220d |

| 13. | 3.5 | 0.4 | 40.5 ± 3.138c |

| 14. | 3.5 | 1.0 | 25.1 ± 1.734a |

Treatment means followed by different letters are significantly different from each other at 5% level of significance (P ≤ 0.05) according to DMRT (each value represents mean ± SE of 10 observations)

Extraction of pyrethrins

For extracting total pyrethrins, callus biomass (1 g) was pulverized in 15 ml ethyl acetate and transferred into 25 ml flasks, followed by sonication for 1 h. This extraction step was repeated twice, and after centrifugation, the extract (supernatant) was concentrated using a Rotavac (30 °C, vacuum, 150 RPM). The obtained crude extract was then eluted with 25 ml of acetonitrile (Ban et al. 2010).

Analyses by reverse phase RP-HPLC

Two different RP-HPLC methods were used to separate pyrethrins from pyrethrum extracts. HPLC instrument LC-8A Shimadzu was used. The column was C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size). The pyrethrins were detected at 220 nm using SPD-M10A Shimadzu PDA detector. Acetonitrile (solvent A) and water (solvent B) used as mobile phase in both methods. The RP-HPLC conditions in the method 1 was set up according to Kasaj et al. (1999). According to this approach, acetonitrile percent was 58% for 0–5 mins, 75% for 5–35 mins and 100% for 35–36 mins and method II is standardized by varying solvent percent which showed good separation and resolution of all the six compounds both in standards and in samples. Acetonitrile percent in method 2 was standardized as follows: 60% for 0–15 min, 80% for 15–25 min, 95% for 25–35 and 60% for 35–40. The flow rate was 1.4 ml/min in both the methods. Further, LCMS analysis carried out using waters 2695 series liquid chromatograph which was connected to the mass spectrometer (Micromass) along with electrospray interface (ESI) operating in positive ion mode was used. LC separation was performed using CI8 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size). Gradient–elution analysis was performed using acetonitrile and water as mobile phase. The flow rate was 1.0 ml/min LC conditions maintained as per standardised method 2.

Repellency test

The repellent activities of callus extracts and Standard were evaluated against the adults of Tribolium castaneum using filter paper impregnation method (Mc Donald et al. 1970). Whatman No.1, filter paper (18 cm diameter) cut into two halves. 100 µl of the test sample was diluted with acetonitrile solvent for the positive controls to make up the volume to 1 ml for applying the extract on one-half of the filter paper as uniform as possible with the help of a micropipette. While 1 ml of callus extract used for the repellency test. The other half was treated with acetonitrile to serve as control. Both the treated and control filter halves were air dried for 15 min to evaporate the solvent completely. After evaporation, both the treated halves were attached lengthwise with cellophane tape and placed inside individual Petri dishes of 18 cm diameter. Twenty adults (1 week old) of T. castaneum were released onto the center of the Petri dish to avoid bias in the aggregation of the adults towards the sample treated or control side. Each Petri dish was then covered with a lid and held in darkness at 27 ± 2 °C and 70–80% RH. Pestanal obtained from Sigma Aldrich Inc, USA and 2% pyrethrum extract purchased from Nitapole, Industries, Kolkata, India as a positive control for the experiment. Each treatment was replicated four times, and the number of insects settled to the treated and control side were counted and recorded at every 2 h interval until 8 h, and the final count was taken at the end of 24 h. The percentage repellency was calculated by Laundani et al. (1955) method. R = (C − T)/C × 100; where T = mean number of insects on treated half; C = mean number of insects on control half. Repellence test was carried out on grain storage insect T. castaneum. Pestanal used as a positive control, and flower extract (2%) and 1 ml of pyrethrum extract from Callus tested for their repellent activity.

In silico analysis

Preparation of protein and ligands

Structure based drug discovery (SBDD) begins with the selection of target protein and proceeds with its interaction with selected ligand molecules. Pyrethrins are a group of six compounds namely, pyrethrin I, II, cinerin I, II, and jasmolin I, II (Hitmi et al. 2000), and hence all the six molecules selected for SBDD and their structures were drawn using Chem-Draw Ultra 6.0 (Fig. 3). 3-D geometrical optimization was done using Chem-sketch V.12.01 and Openbabel; a standalone tool was used to obtain 3D coordinates.

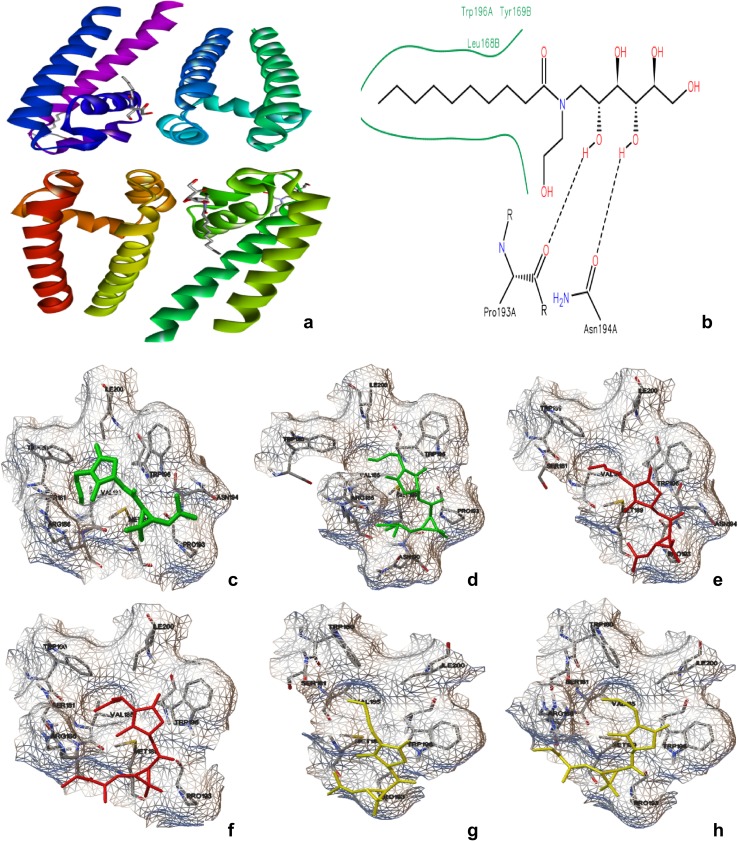

Fig. 3.

a Crystal structure of 4CBC, b binding cavity of 4CBC. Interaction between Cinerin 1 (c), Cinerin 2 (d), Jasmolin 1 (e), Jasmolin 2 (f), Pyrethrin 1 (g) and Pyrethrin 2 (h) with 4CBC

NavMS Sodium Channel Pore receptor was selected as target protein since, the binding and inhibition of prokaryotic sodium channel from Magnetococcus marinus (NavMs) by eukaryotic sodium channel blockers are similar to the human Nav1.1 channel, despite millions of years of divergent evolution between the two types of channels (Bagneris et al. 2014). The protein structure file was retrieved from PDB (4CBC) (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb) and is edited to remove the hetero atoms (Fig. 3a). Later it was added with C-terminal oxygen, polar hydrogen and Gasteiger charges (Raghavendra et al. 2015). The binding site information is obtained from PDB sum server, and the residues forming the pocket were identified (Fig. 3b). Protein–ligand interactive visualization and analysis was carried out in Python molecular viewer V.1.5.6 and discovery studio V.2.5. All the in silico studies were performed on Lenovo G50-80 machine (Intel Core i3- 5005U Processor 2.0 GHz, 4 GB memory).

Molecular docking

Automated docking was used to study the binding interactions of ligand molecules to the binding pocket of the macromolecule. Auto Dock implements a genetic algorithm method to study the appropriate binding modes of the ligand in different conformations (Kollman 1993). For the ligand molecules, all the torsions were allowed to rotate during docking. The grid map was set around the residues forming the active pocket. Grid file was generated using Auto-Grid program, and Lamarckian genetic algorithm and the pseudo-Solis and Wets methods were applied for energy minimization using default parameters. Further, multiple ligands simultaneous docking (MLSD) was performed to study the concurrent binding of different combinations of ligands. MLSD enables the docking of multiple ligands to a single binding site of a single target molecule in a single simulation. The multiple ligands can be a mixture of substrates, cofactors, or metal ions (Li and Li 2010). The present implementation of MLSD adopts the algorithms and scoring function of Auto-Dock 4.2 and helps in analyzing the interaction between multiple ligands with the target protein (Raghavendra et al. 2015). It has reported that, the combination of Pyrethrin I with II is highly insecticidal and hence, any combination of cinerin and jasmolin with Pyrethrin I and Pyrethrin II is expected to yield encouraging results.

Data analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncun’s post-test. P < 0.01 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Tissue culture

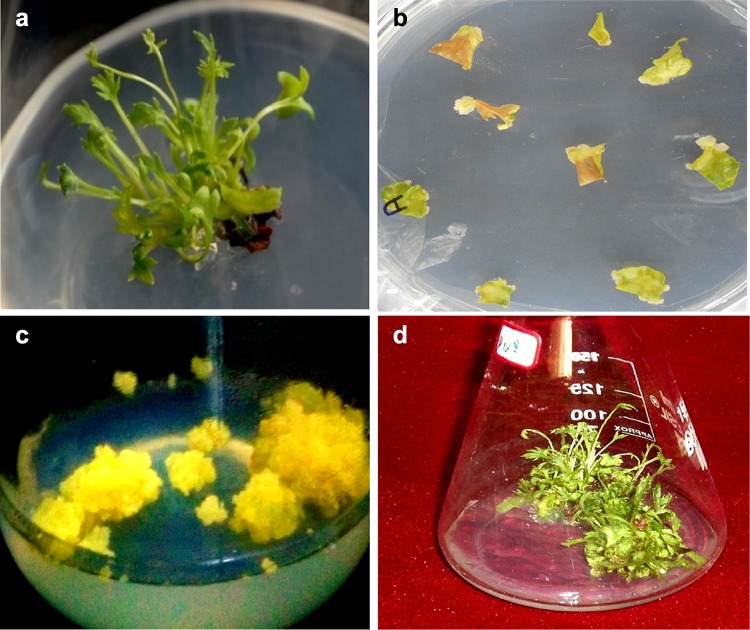

The inoculated seeds were germinated about 20% after 2 months of inoculation (Fig. 1a) in culture vial containing MS medium. These In vitro seedlings used as an explant for the callus induction using MS media fortified with different growth regulators as mentioned in Table 1. The initiation of callus was observed from hypocotyl and cotyledon explants after two weeks of inoculation and grew as pale yellowish friable callus after the fourth week (Fig. 1b, c). Among the different growth regulators and concentrations, 2,4-D (2 mg/l) and kinetin (0.4 mg/l) was found to be more ideal for the callus production (Fig. 1c). Similarly, it was also observed that BAP (2 mg/l) and Kin (0.2 mg/l) fortified MS medium was found to be the best for multiplication of shoot (20-fold) (Fig. 1d). Among three additional supplements, the medium fortified with adenine sulphate (40 mg/l) showed the faster callus growth (100%) when compared to other combination. However, there is no significant increase in the pyrethrins content in any additional supplemented media. In the present study, it has been observed that when MS medium fortified with adenine Sulphate showed early initiation of callus formation (within 5–7 days callus formation was noticed) when compared to the MS medium devoid of adenine sulphate (more than 15 days). The media augmented with 0.01 and 0.05% colchicine and 5% coconut water showed callus formation. Further, the different combination of colchicine (0.001, 0.01 and 0.05%) and coconut water (5, 10 and 15%) along with 2,4-D (2 mg/l), Kn (0.4 mg/l) and adenine sulphate (40 mg/l) are not shown any promising result in pyrethrin content.

Fig. 1.

Different stages of in vitro propagation of C. cinerariaefolium. a In vitro seedlings of C. cinerariaefolium on M S medium, b initiation of callus from hypocotyl and cotyledon explants on MS Medium supplemented with 2,4-D (2 mg/l) and kn (0.4 mg/l), c profound callus formation, d Multiple shoots formation from C. cinerariaefolium callus on MS Medium supplemented with BAP (2 mg/l) and Kin (0.2 mg/l)

HPLC analyses

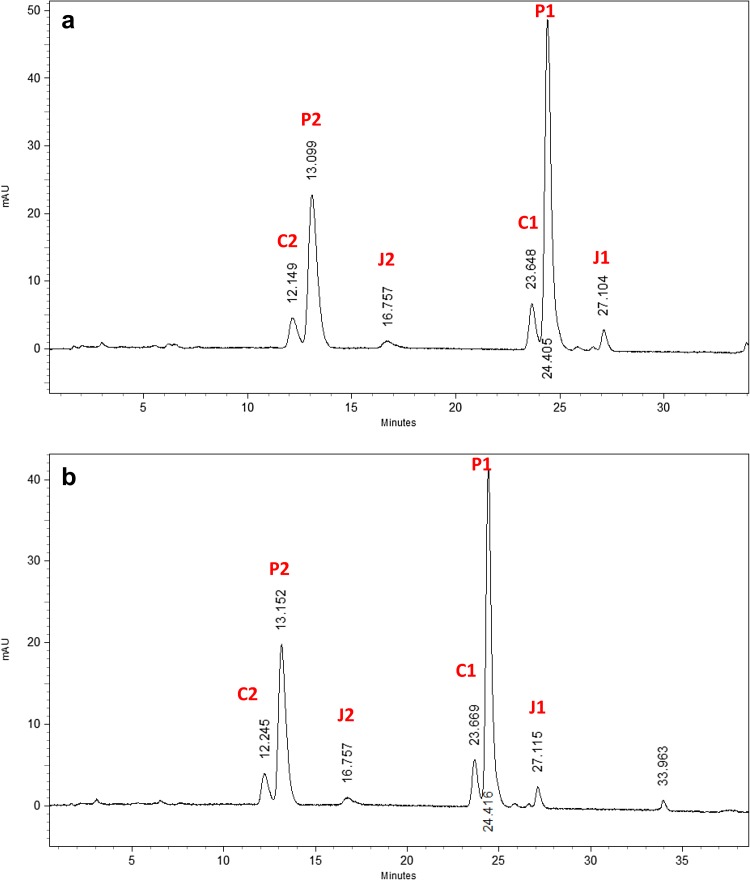

The callus formed in all the growth regulators combinations and with or without additional supplements were subjected to pyrethrins analysis by HPLC method. Among two different RP-HPLC methods, the second method (minor modification from Kasaj et al. 1999) showed better separation and resolution of all the six compounds of pyrethrin in both standards and samples (Fig. 2a, b). The HPLC profile of callus and shoot extracts were compared with commercial pyrethrum extract and standard Pestenal (Fig. 2). The concentrations (DW) of Pyrethrin were quite high in callus when compared to shoot culture. Callus was found to contain a total pyrethrins content of about 17.5 µg/g, which is more than those in natural flowers of certain Pyrethrum cultivars having 0.8% and about 80% of that in high yielding cultivars (2% DW). There is no significant change in pyrethrin content noticed in the callus grew on the adenine sulphate alone and along with coconut water and colchicine, when compared to the callus grown on MS medium with 2,4-D and Kn. Figure 2a, b describe the HPLC patterns of pyrethrins in callus and Pestenal. The callus grew on the adenine sulphate alone and along with coconut water and colchicine showed the presence of pyrethrin content, but the results were not significant in pyrethrin elicitation, when compared to the callus grown on MS medium with 2,4-D and Kn. Studies by other researchers also established that 80% of insecticidal properties exist in cultured cells of C. cinerariaefolium (Rajasekaran et al. 1991; Hitmi et al. 2000) when compared with natural plants.

Fig. 2.

a HPLC Data of Pyrethrin standard and b Callus extract of C. cinerariaefolium. Whereas, C 2 Cinerin II, P 2 Pyrethrin II and J 2 Jasmolin II, similarly C 1 Cinerin I, P 1 Pyrethrin I and J 1 Jasmolin I

Repellency test

The repellent effects of various pyrethrum sources on the adults of T. castaneum are presented in Table 2. The results indicated that the effect of pyrethrum obtained from the callus culture proved significantly superior (P ≤ 0.5) to repel the adults away from the treated filter disc compared to pestanal standard after 1 h treatment. Among the treatments, the maximum repellence (93.2%) of T. castaneum adults observed in the callus extract upon 8 h exposure. Previously, Rajasekaran et al. (1991) reported the comparable efficacy of pyrethrins obtained from leaf callus of C. cinerariaefolium with that of natural pyrethrins on the adults of Drosophila melanogaster. It was also observed in the present study that there was no apparent change in the repellent effect after 2 h of exposure in any of the treatments. The outcome of the study augments the fact that pyrethrum can induce immediate knockdown effects on insects upon treatment. Though considering T. castaneum as one of the tolerant insect species to pyrethrum (Lloyd 1973), it presents the promising repellent effects of callus extract on this particular species.

Table 2.

Repellent effects of different pyrethrum sources on rust red-flour beetle T. castaneum

| Treatments | % Repellence recorded at different time intervals (mean* ± SE) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | 4 h | 8 h | 24 h | |

| Callus extract | 61.01 ± 11.10b | 76.27 ± 3.69a | 83 ± 3.00a | 86.20 ± 4.20a | 93.22 ± 3.36a | 93.38 ± 3.30a |

| Commercial pyrethrum extract (2%) | 48.56 ± 3.78a,b | 69.18 ± 9.54a | 82.49 ± 8.51a | 84.80 ± 3.80a | 89.00 ± 5.00a | 90.36 ± 1.24a |

| Pestanal standard | 45.78 ± 4.22a | 65 ± 5.00a | 78.59 ± 3.75a | 79.27 ± 5.91a | 84.23 ± 7.21a | 91.75± 2.75a |

The means followed by the same letter in the same column are not significantly different at (P = 0.5) according to Tukey’s test

SE standard error

*Values are mean of two replications

In silico analysis

The results of the in silico docking studies of selected molecules with NavMS Sodium Channel Pore receptor are shown in Table 3, and their binding conformations are shown in Fig. 3c–h. The confirmations with minimum binding energy at zero root mean square deviations (RMSD) were considered as better binding in each study. Among the tested molecules, Pyrethrin II showed better binding concerning to its binding energy (− 5.24 kJ/mol) followed by Pyrethrin I and Jasmoline II with binding energies of − 5.18 and − 4.73 kJ/mol respectively. The order of binding continues with Jasmolin I (− 4.63 kJ/mol), Cinerin I (− 4.51 kJ/mol) and Cinerin II (− 4.07 kJ/mol). Different combinations of Pyrethrin I and II with Cinerin I and II, and Jasmoline I and II were studies for their binding efficiency using MLSD approach. The results revealed that there is a higher binding affinity for Pyrethrin I and II complexes with a minimum binding energy of − 5.53 kJ/mol compared to rest of the combinations. Cinerin and Jasmoline derivatives showed better compatibility with Pyrethrin 2 than Pyrethrin 1 which can be seen in their complexes regarding their binding energies (Table 4).

Table 3.

Single ligand docking results for different pyrethrins

| Molecules | Binding energy (kJ/mol) | Intermol energy (kJ/mol) | Total internal energy (kJ/mol) | Torsional energy (kJ/mol) | Unbound energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cinerin 1 | − 4.51 | − 6.30 | − 0.87 | 1.79 | − 0.87 |

| Cinerin 2 | − 4.07 | − 6.76 | − 1.36 | 2.68 | − 1.36 |

| Jasmolin 1 | − 4.63 | − 6.72 | − 1.05 | 2.09 | − 1.05 |

| Jasmoline 2 | − 4.73 | − 6.82 | − 1.07 | 2.09 | − 1.07 |

| Pyrethrin 1 | − 5.18 | − 7.86 | − 1.12 | 2.68 | − 1.12 |

| Pyrethrin 2 | − 5.24 | − 7.92 | − 1.00 | 2.68 | − 1.00 |

Table 4.

Synergistic effect of different pyrethrins on multiple ligands simultaneous docking

| Molecules | Binding energy (kJ/mol) | Intermol energy (kJ/mol) | Total internal energy (kJ/mol) | Torsional energy (kJ/mol) | Unbound energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrethrin I + Cinerin I | − 4.74 | − 6.83 | − 1.11 | 2.09 | − 1.11 |

| Pyrethrin I + Cinerin II | − 3.69 | − 6.37 | − 0.95 | 2.68 | − 0.95 |

| Pyrethrin 1 + Jasmolin I | − 4.58 | − 6.67 | − 1.02 | 2.09 | − 1.02 |

| Pyrethrin I + Jasmoline II | − 5.14 | − 7.83 | − 1.21 | 2.68 | − 1.21 |

| Pyrethrin I + Pyrethrin II | − 5.53 | − 8.21 | − 1.07 | 2.68 | − 1.07 |

| Pyrethrin II + Cinerin I | − 5.25 | − 7.93 | − 1.23 | 2.68 | − 1.23 |

| Pyrethrin II + Cinerin II | − 4.26 | − 6.94 | − 1.06 | 2.680 | − 1.06 |

| Pyrethrin II + Jasmolin I | − 4.33 | − 6.42 | − 1.13 | 2.09 | − 1.13 |

| Pyrethrin II + Jasmoline II | − 5.21 | − 7.90 | − 1.33 | 2.68 | − 1.33 |

Discussion

Recently, plant cell and transgenic techniques are promising potential alternative sources for the production of high-value secondary metabolites of industrial importance (Rao and Ravishankar 2002; George et al. 2008; Hussain et al. 2012). Hence plant cell culture systems offer an industrially attractive method for the production of a wide variety of plant-derived biochemical, such as pyrethrins. Pyrethrum is a tufted perennial herb of temperate origin and mainly cultivated at higher altitudes in tropical countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Ecuador (Jovetic and De Gooijer 1995). Few high altitude areas of India were growing C. cinereriaefolium. Many studies have explored the influence of growth regulators, especially auxins and cytokinins on the initiation and proliferation of callus and even in the expression or production of secondary metabolites (Rao and Ravishankar 2002; Mahadevappa et al. 2014). In this regard, many researchers have exploited many growth regulators to obtain callus from the C. cinerariaefolium and T erecta for the augmentation of the pyrethrin content (Ravishankar et al. 1989; Zito and Tio 1990; Sarin 2004). Earlier studies also demonstrated feasibility for the production of pyrethrin from the callus, cell and hairy root cultures from C. cinerariaefolium. There was a close correlation between pyrethrin content in Chrysanthemum callus cultures and that in original plants. The plant part used to initiate the in vitro culture has little influence on pyrethrin production. Shoot cultures synthesized pyrethrins to a level almost similar to that of in vivo plants, whereas roots failed to synthesize this compound (Zito and Tio 1990; Rajshekaran et al. 1991; Hitami et al. 2000). Similarly, in the present study, different explants were used to obtain callus and evaluate pyrethrin concentration. Out of four explants, hypocotyl and cotyledon explants showed the good response for the callus formation in the various hormones provided MS media. In the interim, many scientists have also been applied many physical and chemical parameters to improve the pyrethrin content in the T erecta and C. cinerariaefolium callus. The biosynthetic ability of pyrethrin was increased in the callus of T erecta in the medium supplemented with the exogenous addition of ascorbic acid (Khanna and Khanna 1976). Similarly, the light intensity at 4000 lux for 16 h photoperiod stimulated the production of pyrethrin (Staba et al. 1984). Hitmi et al. (2000) revealed that the callus under red or blue light at 60 µmol/m2/s had decreased the production of pyrethrin. It has also been found that nitrogen stress can enhance production of pyrethrin content in the callus (Rajasekaran et al. 1991) but, the sugar or phosphate stress may decrease the pyrethrin content in the callus. In the present study, the promising augmentation of pyrethrin (17.5 µg/g) was noticed, which is quite a good yield when compared to earlier studies. However, in the present work, additional supplements like adenine sulphate, coconut water and colchicine were also assessed for its effect on the enhancement of pyrethrin content in callus either in single or combination. Among these additional supplements, adenine sulphate encourages the vigorous callus growth, but all the three additional supplement including adenine sulphate fail to elicit the pyrethrin concentration in the callus.

To analyse and quantify the pyrethrin content in the sample, several methods are being used by many researchers, such as AOAC/titrimetric procedure. The long saponification steps and it does not quantify the six pyrethrins independently are the main drawbacks of the methods (Carlson 1995; Hitmi et al. 2000). Gas–liquid chromatography (GLC) can also be considered for the assessment of pyrethrin, as it offers the advantages of speed and reduced handling. However, it has the drawback of degradation of pyrethrins II when compare to pyrethrins I (Carlson 1995). Therefore, various researchers found the HPLC and RP-HPLC protocol as an appropriate analytical method for quantification of pyrethrin independently (Wang et al. 1997; Hitmi et al. 2000). In the present paper, RP-HPLC used to analyse and quantify the pyrethrin content in the samples. Two different procedures are considered for conducting the quantification of pyrethrin. Among two procedure, the second procedure found to be best due to its high resolution and separation of all six pyrethrin contents in the sample. The flow percentage of acetonitrile gave considerable resolution for the quantification of pyrethrin in the sample. Further, pyrethrins identification and quantitation method have been confirmed using LCMS to quantify the individual components of pyrethrins in the plant extracts.

Despite the localized traditional use of plant materials and evaluation of many phytochemicals for their insecticidal activities, a very few number of botanicals such as neem, pyrethrum and rotenone are only currently available for the widespread application (Isman 1997). Among them, the pyrethrins are often considered for food protection against storage pests. It is reported that the pyrethrin content in natural pyrethrum synthesized from the flowers of C.cinerariifolium contains about 1–2%, relative to its dry weight (Casida and Quistad 1995). Interestingly, in the present study, the callus extract of C. cinerariaefolium was found to contain pyrethrin content more than those in natural flowers of certain cultivars. Hence, the repellent effects of the obtained callus were compared with the pure standard, pestanal and 2% commercial formulation. The insecticidal activity of pyrethrum has been reported on many of the occasions. For instance, field evaluation of pyrethrum formulation by Warui et al. (1990) indicated satisfactory efficacy on three storage pests viz., S. zeamais, S. cereallella and T. castaneum. Similarly, Kimani and Sum (1999) found the promising insecticidal activity of essential oils obtained from pyrethrum flowers on the adults of Sitophilus oryzae and T. castaneum and further recommended the utilization of essential oils for pest management. In addition, Mulungu et al. (2010) reported that the pyrethrum flower powder offered protection to stored maize against Prostephanus truncatus and S. zaemais infestation. It is evident from the study and previous reports that, pyrethrins have a wide range of toxicity against many storage pests. Hence, it becomes imperative to their usage for stored product insect control, in the current scenario of increasing awareness of the harmful effects of synthetic pesticides.

The insecticidal actions of pyrethroids depend on their ability to bind to and disrupt voltage-gated sodium channels of insect nerves (Soderlund 2005). In the present studies, the molecular docking of pyrethrins with NavMS Sodium Channel Pore receptor supported the repellency activity showed by the pyrethrin extract. The multiple ligand simultaneous docking (MLSD) method was adopted to know the effect of different pyrethrins in combination (Table 4) such as pyrethrin I and II, Pyrethrin I and Jasmoline I or II, etc. Among different combinations, pyrethrin I and II (binding energy = − 5.53 kJ/mol, intermol energy = − 8.21 kJ/mol, total internal energy = − 1.07 kJ/mol, torsional energy = 2.68 kJ/mol, and unbound energy = − 1.07) found to be the best combination for the strong repellency activity, and it is followed by Pyrethrin II + Cinerin I and Pyrethrin II + Jasmoline II. Therefore, it is evident by the result, pyrethrins disrupt nerve function by altering the rapid kinetic transitions between conducting (open) and non-conducting (closed or inactivated) states of voltage-gated sodium channels that underlie the generation of nerve action potentials (Soderlund 2005). Earlier, Elliott (1989) work is evident for the role of Pyrethrins I in knock-down activity and pyrethrins II for its better kill effect. Similarly, Zong-Mao and Yun-Hao (1996), found to be Pyrethrin I and II as the strong insecticidal activity when compared to other pyrethrin components.

Conclusion

The present paper is helpful to understand the role of plant growth regulators for the formation of callus and augmentation of pyrethrins (17.5 µg/g) from C. cinerariaefolium. Further, the repellency test and in silico analysis are used to understand the bio-efficacy of pyrethrum extracts from callus on insect Tribolium sp. These results are encouraging, and this can be further used to establish suspension cultures and bioreactor studies to extrude the pyrethrum content.

Acknowledgements

The work was funded by CSIR, New Delhi (Network project BSC-0105) and authors express their gratitude to the Director, CSIR-Central Food Technological Research Institute, Mysore, for his support.

Author contributions

NPS, BLN and PM designed the research. PM, SKS and MS performed the experiments and ARSJ and PM performed in silico analysis. PM wrote the paper. All authors approved the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest from the funding sources or any authors.

References

- Allan CG, Miller TA. Long-acting pyrethrin formulations. In: Casida JE, editor. Pesticides and alternatives: innovative chemical and biological approaches to pest control. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1990. pp. 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Bagneris C, Paul GD, Claire EN, David CP, Irene N, David EC, Wallace BA. Prokaryotic NavMs channel as a structural and functional model for eukaryotic sodium channel antagonism. PNAS USA. 2014;111:1–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406855111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban D, Sladonja B, Luki M, Luki I, Lušeti V, Gani KK. Comparison of pyrethrins extraction methods efficiencies. Afr J Biotechnol. 2010;9:2702–2708. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DT. Pyrethrum extract, refining and analysis. In: Casida JE, Quistad GB, editors. Pyrethrum flowers. Production, chemistry, toxicology and uses. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc; 1995. pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Casida JE, Quistad GB. Pyrethrum flowers: production, chemistry, toxicology and uses. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Crombie L. Chemistry and biosynthesis of natural pyrethrins. Pest Manag Sci. 1980;11:102–118. doi: 10.1002/ps.2780110203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies T, Field L, Usherwood P, Williamson M. DDT, pyrethrins, pyrethroids and insect sodium channels. IUBMB life. 2007;59:151–162. doi: 10.1080/15216540701352042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekins S, Mestres J, Testa B. In silico pharmacology for drug discovery: methods for virtual ligand screening and profiling. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:9–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias P. Insecticides-development of safer and more effective technologies. London: InTech; 2013. The use of deltamethrin on farm animals; p. 495503. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott M. The pyrethroids: early discovery, recent advances and the future. Pest Sci. 1989;27:337–351. doi: 10.1002/ps.2780270403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency Federal insecticide, fungicide and rodenticide act (FIFRA); good laboratory practice standards. Final rule. 40 CFR Part 160. Fed Reg 1989b. 1989;54:34067–34074. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira LG, dos Santos RN, Oliva G, Andricopulo AD. Molecular docking and structure-based drug design strategies. Molecules. 2015;20:13384–13421. doi: 10.3390/molecules200713384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii Y, Shimizu K. Regeneration of plants from achenes and petals of Chrysanthemum coccineum. Plant Cell Rep. 1990;8:625–627. doi: 10.1007/BF00270069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EF, Hall MA, de Klerk GJ. Plant propagation by tissue culture volume 1: the background. Dordrecht: Springer; 2008. pp. 355–402. [Google Scholar]

- Hitmi A, Coudret A, Barthomeuf C. The production of pyrethrins by plant cell and tissue cultures of Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium and Tagetes species. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2000;19:69–89. doi: 10.1080/07352680091139187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain MS, Fareed S, Saba Ansari M, Rahman A, Ahmad IZ, Saeed M. Current approaches toward production of secondary plant metabolites. J Pharm Bioall Sci. 2012;4:10. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.92725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isman MB. Neem and other botanical insecticides: barriers to commercialization. Phytoparasitica. 1997;25:339–344. doi: 10.1007/BF02981099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jovetic S, De Gooijer CD. The production of pyrethrins by in vitro systems. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1995;15:125–138. doi: 10.3109/07388559509147403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasaj D, Rieder A, Krenn L, Kopp B. Separation and quantitative analysis of natural pyrethrins by high-performance liquid chromatography. Chromatographia. 1999;50:607–610. doi: 10.1007/BF02493668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna P, Khanna R. Endogenous free ascorbic acid & effect of exogenous ascorbic acid on growth & production of pyrethrins from in vitro tissue culture of Tagetes erecta L. Indian J Exp Biol. 1976;14:630–631. [Google Scholar]

- Kimani S, Sum K. Bioefficacy of essential oils extracted from pyrethrum vegetable waxy resins and green oils against stored product insect pests, Tribolium castaneum (Hbst.) and Sitophilus oryzae (L.) Pyret Post. 1999;20:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kollman P. Free energy calculations: applications to chemical and biochemical phenomena. Chem Rev. 1993;93:2395–2417. doi: 10.1021/cr00023a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laundani H, Davis DF, Swank GR. A laboratory method of evaluating the repellency of treated paper to stored-product insects. TAPPI. 1955;38:336341. [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Li C. Multiple ligand simultaneous docking: orchestrated dancing of ligands in binding sites of protein. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:2014–2022. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Yin L, Jongsma M, Wang C. Effects of light, hydropriming and abiotic stress on seed germination, and shoot and root growth of pyrethrum (Tanacetum cinerariifolium) Ind Crops Prod. 2011;34:1543–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C. The toxicity of pyrethrins and five synthetic pyrethroids, to Tribolium castaneum (Herbst), and susceptible and pyrethrin-resistant Sitophilus granarius (L.) J Stored Prod Res. 1973;9:77–92. doi: 10.1016/0022-474X(73)90014-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevappa P, Ramesh C, Krishna V, Raghavendra S. Influence of different cytokinins on direct shoot regeneration from the different explants of Carthamus tinctorius L. Var Annigeri-2 (A high oil-yielding variety) Ann Biol Res. 2014;5:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Donald LL, Guy RH, Speirs RD. Preliminary evaluation of new candidate materials as toxicants, repellents and attractants against stored product insects—I. Marketing research report no. 882. Washington, DC: Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 1970. p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Mulungu L, Kubala M, Mhamphi G, et al. Efficacy of protectants against maize weevils (Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky) and the larger grain borer (Prostphanus truncatus Horn) for stored maize. Int J Plant Sci. 2010;1:150–154. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra S, Rao SA, Kumar V, Ramesh C. Multiple ligand simultaneous docking (MLSD): a novel approach to study the effect of inhibitors on substrate binding to PPO. Comput Biol Chem. 2015;59:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran T, Ravishankar G, Rajendran L, Venkataraman L. Bioefficacy of pyrethrins extracted from callus tissues of Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium. Pyret Post. 1991;18:52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rao SR, Ravishankar G. Plant cell cultures: chemical factories of secondary metabolites. Biotechnol Adv. 2002;20:101–153. doi: 10.1016/S0734-9750(02)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravishankar G, Rajasekaran T, Sarma K, Venkataraman L. Production of pyrethrins in cultured tissues of pyrethrum (Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium Vis) Pyret Post. 1989;17:66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sarin R. Insecticidal activity of callus culture of Tagetes erecta. Fitoterapia. 2004;75:62–64. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoenig GP. Mammalian Toxicology of pyrethrum extract. In: Casida JE, Quistad GB, editors. Pyrethrum flowers. Production, chemistry, toxicology, and uses. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 249–257. [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund DM. Sodium channels. In: Gilbert L, Iatrou K, Gill S, editors. Comprehensive molecular insect science. New York: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Staba EJ, Nygaard BG, Zito SW. Light effects on pyrethrum shoot cultures. PCTOC. 1984;3:211–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00040339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Latum E, Gerrits R. Bio-pesticides in developing countries: prospects and research priorities. Nairobi: ACTS; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wang IH, Subramanian V, Moorman R, Burleson J, Ko J. Direct determination of pyrethrins in pyrethrum extracts by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection. J Chromatogr A. 1997;766:277–281. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(96)00969-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warui C, Kega V, Onyango R. Evaluation of an improved pyrethrum formulation in the control of maize pests in Kenya. Pyret Post. 1990;18:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zito SW, Tio CD. Constituents of Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium in leaves, regenerated plantlets and callus. Phytochemistry. 1990;29:2533–2534. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(90)85182-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zong-Mao C, Yun-Hao W. Chromatographic methods for the determination of pyrethrin and pyrethroid pesticide residues in crops, foods and environmental samples. J Chromatogr A. 1996;754:367–395. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(96)00490-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]