Abstract

Background:

A new functional movement assessment, known as the Fusionetics− Movement Efficiency (ME) Test, has recently been introduced in the literature. Before the potential clinical utility of the ME Test can be examined, the reliability of this assessment must be established.

Purpose:

To examine the intra-rater test-retest reliability of the Fusionetics− ME Test.

Study Design:

Cross-sectional.

Methods:

ME Test data were collected among 23 (6 males, 17 females) university students (mean ± SD, age = 25.96 ± 3.16 yrs; height = 170.70 ± 9.96 cm; weight = 66.89 ± 12.67 kg) during sessions separated by 48 hours (Day 1, Day 2). All participants completed the seven sub-tests of the ME Test: 2-Leg Squat, 2-Leg Squat with Heel Lift, 1-Leg Squat, Push-Up, Shoulder Movements, Trunk Movements, and Cervical Movements. Overall ME Test scores and ME Test scores for each individual sub-test were calculated on a scale of 0 – 100 (worst – best) based on commonly observed movement compensations associated with each sub-test.

Results:

Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC3,1) statistics indicated that the intra-rater test-retest reliability of the Overall ME Test and individual sub-tests ranged from fair-to-excellent (ICC3,1 range = 0.55 – 0.84). Statistically significant differences in ME Test scores were identified between Day 1 and Day 2 among the 2-Leg Squat with Heel Lift (p = 0.015) and Cervical Movements (p = 0.005) sub-tests. In addition, a large range in the standard error of the measure (SEM) and minimal detectable change values (MDC90% & MDC95%) were identified within individual sub-tests of the ME Test (SEM range = 7.05 – 13.44; MDC90% range = 16.40 – 31.27; MDC95% range = 19.53 – 37.25), suggesting that the response stability varies among these individual sub-tests. Prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa statistics (κPABA) suggest that 55 of the 60 (92%) individual movement compensations hold moderate-to-almost perfect intra-rater test-retest reliability (κPABA range = 0.30 – 1.00).

Conclusions:

Excellent intra-rater test-retest reliability of the Overall ME Test score was identified, and thus, clinicians can reliably utilize the Fusionetics− ME Test to assess change in functional movement quality across time. However, caution should be taken if utilizing an individual sub-test to assess functional movement quality over time.

Level of Evidence:

2b

Keywords: Functional movement quality assessment, movement screening, movement system, response stability, systematic bias

INTRODUCTION

Previous research has identified relationships between functional movement quality and musculoskeletal injury risk, as well as athletic performance and fitness.1 As a result, the utilization of various movement screening assessments by practitioners and clinicians to assess functional movement quality has grown tremendously over recent years.2 Such assessments include: the Functional Movement Screen (FMS−), the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS), several different single-leg squat screens, and various drop and/or tuck jump assessments.3

Recently, a new assessment of functional movement quality has been introduced in the literature,4,5 known as the Fusionetics− Movement Efficiency (ME) Test. This assessment was developed by Fusionetics, LLC (Milton, GA) and is associated with the Fusionetics− Human Performance System. Similar to the FMS−,6,7 the ME Test utilizes seven sub-tests that require an individual to complete various movement patterns. However, the ME Test is graded based on the presence of specific movement compensations that are commonly observed during each sub-test. The Fusionetics− Human Performance System then uses computer-based proprietary algorithms to generate a 0 – 100 (worst – best) score based on the movement compensations observed throughout the entire assessment, known as the Overall ME Test score, as well as an ME Test score for each individual sub-test.

Due to the utilization of discrete individual movement compensations in the scoring algorithms, the ME Test scores may be sensitive to changes in functional movement quality as a result of various corrective exercise interventions that address the specific movement compensations identified during the sub-tests. Due to previous research questioning the clinical utility of the FMS− to monitor changes in movement quality,8,9 the ME Test may hold potential to be a more valid and/or clinically useful assessment of functional movement quality. However, before the validity or clinical utility of the ME Test can be examined, the reliability and response stability of the assessment must first be established.10 Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to examine the intra-rater test-retest reliability and response stability of the Fusionetics− ME Test.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty-three participants (6 males, 17 females) with no prior exposure to the ME Test or the Fusionetics− Human Performance System volunteered to participate in this study (mean ± SD, age = 25.96 ± 3.16 yrs; height = 170.70 ± 9.96 cm; weight = 66.89 ± 12.67 kg; body mass index = 22.80 ± 2.80 kg/m2). All participants were current students at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (Milwaukee, WI). Participants were free of any musculoskeletal injury or muscular pain that required medical attention for the three months prior to participating in the study. All components of this study protocol were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and all participants provided written informed consent to this protocol prior to any data collection.

Protocol

All participants attended two data collection sessions (Day 1, Day 2) separated by 48 hours. To mitigate the potential influence of dehydration and/or muscle soreness, participants were instructed to not engage in any strenuous physical activity the 48 hours leading up to Day 1 of data collection, as well as in-between Day 1 and Day 2 data collection sessions. All ME Tests were administered, and subsequent data were collected, by the same researcher (K.T.E.) during both testing sessions. This researcher has been a certified athletic trainer (ATC) for 24 years, with greater than two years of prior experience administering the ME Test at the time of data collection. Participants were not informed of any test results between sessions.

ME Test

The ME Test was administered according to guidelines provided by Fusionetics, LLC (Appendix A). In brief, all participants completed the ME Test in athletic apparel and without shoes. Each participant completed each sub-test in the following order: 2-Leg Squat (Figure 1), 2-Leg Squat with Heel Lift (Figure 2), 1-Leg Squat (Figure 3), Push-Up (Figure 4), Shoulder Movements (Figure 5), Trunk Movements (Figure 6), and Cervical Movements (Figure 7). Participants were provided 5-10 trials of each sub-test and the most proficient trial (i.e., the least number of compensations) of each sub-test was used for scoring purposes.

Figure 1.

2-Leg Squat sub-test, A: Start Position (Front View); B: End Position (Front View); C: Start Position (Side View); D: End Position (Side View); E: Start Position (Back View); F: End Position (Back View).

Figure 2.

2-Leg Squat with Heel Lift sub-test, A: Start Position (Front View); B: End Position (Front View); C: Start Position (Side View); D: End Position (Side View); E: Start Position (Back View); F: End Position (Back View).

Figure 3.

1-Leg Squat sub-test, A: Start Position; B: End Position.

Figure 4.

1-Push-Up sub-test, A: Start Position; B: End Position.

Figure 5.

Shoulder Movements sub-test, A: Shoulder Flexion – Start Position; B: Shoulder Flexion – End Position; C: Shoulder Internal Rotation – Start Position; D: Shoulder Internal Rotation – End Position; E: Shoulder External Rotation – Start Position; F: Shoulder External Rotation – End Position; G: Shoulder Horizontal Abduction – Start Position; H: Shoulder Horizontal Abduction – End Position.

Figure 6.

Trunk Movements sub-test, A: Trunk Lateral Flexion – Start Position; B: Trunk Lateral Flexion – End Position; C: Trunk Rotation – Start Position; D: Trunk Rotation – End Position.

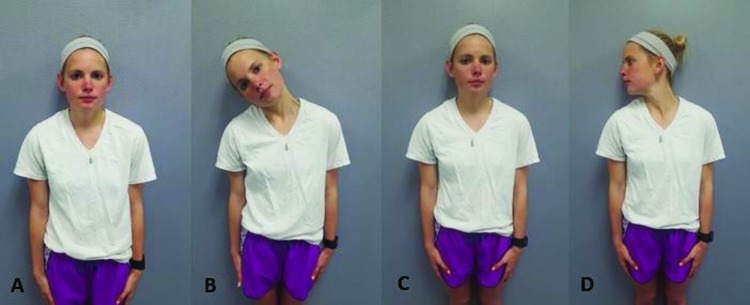

Figure 7.

Cervical Movements sub-test, A: Cervical Lateral Flexion – Start Position; B: Cervical Lateral Flexion – End Position; C: Cervical Rotation – Start Position; D: Cervical Rotation – End Position.

Each sub-test was scored in real-time in a binomial (yes/no) fashion based on a standard set of movement compensations commonly observed during each sub-test (Appendix B). In total, 60 compensations are scored across all sub-tests of the ME Test. After scoring each sub-test, these binomial data were then entered into the Fusionetics− Human Performance System. This online platform utilizes a proprietary algorithm to calculate a ME Test score for the overall assessment (i.e., the Overall ME Test score), as well as a ME Test score for each individual sub-test. These ME Test scores are considered interval-level data and range from 0 – 100 (worst – best).

Statistical Analyses

In order to assess the intra-rater test-retest reliability of the interval ME Test score data, two-way mixed effects model (3,1) intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC3,1) were utilized.11 In addition, to examine for potential systematic bias,12 separate repeated measure analyses of variance (RM ANOVAs) were calculated between Day 1 and Day 2 ME Test scores. All ICC3,1 statistics and RM ANOVAs were calculated using IBM SPSS 22 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and an alpha < 0.05 determined statistically significant differences for all RM ANOVAs.

The response stability of the ME Test scores were further examined by calculating the standard error of the measure (SEM) statistics.13 SEM statistics were calculated by taking the square root of the mean square of the residual term () from the RM ANOVAs.11 Finally, minimal detectable change values at both 90% (MDC90%) and 95% (MDC95%) levels of confidence were calculated based upon the previously calculated SEMs

in order to provide practitioners with both a liberal and a conservative assessment of ME Test score change characteristics.13 ICC3,1 statistics were interpreted according to guidelines previously suggested in the literature: poor (ICC3,1 < 0.39); fair (0.40 < ICC3,1 < 0.59); good (0.60 < ICC3,1 < 0.74); and excellent (ICC3,1 > 0.75).14

In order to assess the intra-rater test-retest reliability of the binomial movement compensation data of each individual sub-test of the ME Test, percent observed agreement (%) and kappa statistics were calculated.12 However, to correct for asymmetrical distribution of the binomial data,15,16 prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa statistics (κPABA) were calculated, opposed to standard kappa statistics.17 κPABA statistics were calculated using Diagnostic and Agreement Statistics (DAG_Stat, Parkville, Victoria, Australia) open source statistical software.18 κPABA statistics were interpreted according to guidelines previously suggested in the literature:19 poor (κPABA < 0.00); slight (0.00 < κPABA < 0.20); fair (0.21 < κPABA < 0.40); moderate (0.41 < κPABA < 0.60); substantial (0.61 < κPABA < 0.80); and almost perfect (κPABA > 0.81).

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics (mean ± SD) of Day 1 and Day 2 ME Test scores, as well as ICC3,1, SEM, MDC90%, MDC95% statistics are provided in Table 1. The ICC3,1 statistic of 0.84 indicates excellent intra-rater test-retest reliability of the Overall ME Test scores. In addition, the ICC3,1 statistics indicate that the intra-rater test-retest reliability of the individual sub-tests ranged from fair-to-excellent (ICC3,1 range = 0.55 – 0.84). However, results of the RM ANOVAs identified statistically significant differences in ME Test scores between Day 1 and Day 2 among the 2-Leg Squat with Heel Lift (p = 0.015) and Cervical Movements (p = 0.005) sub-tests, indicating potential systematic bias within these two sub-tests. No significant differences were identified between Day 1 and Day 2 among the Overall ME Test scores, as well as among the ME Test scores of the other individual sub-tests. The MDC95% statistic of 12.68 associated with the Overall ME Test score indicates that a change in ME Test score of 12.68 points is required for this change in overall functional movement quality to be considered “real” (i.e., outside of the error associated with the measure itself).11,13 However, a large range in SEM and MDC statistics were identified within the individual sub-tests of the ME Test (SEM range = 7.05 – 13.44; MDC90% range = 16.40 – 31.27; MDC95% range = 19.53 – 37.25), suggesting that the response stability varies among the individual sub-tests.

Table 1.

ME Test intra-rater test-retest statistics

| Descriptive Statistics (mean ± SD)* | Reliability and Response Stability Statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Day 1 | Day 2 | ICC3,1 | SEM | MDC90% | MDC95% | |

| Overall ME Test Score | 50.27 ± 12.20 | 47.63 ± 10.42 | 0.84 | 4.57 | 10.63 | 12.68 | |

| ME Sub-Test Scores | |||||||

| 2-Leg Squat | 61.35 ± 16.94 | 61.79 ± 12.75 | 0.71 | 8.03 | 18.68 | 22.26 | |

| 2-Leg Squat with Heel Lift† | 74.64 ± 10.85 | 69.13 ± 11.41 | 0.60 | 7.05 | 16.40 | 19.53 | |

| 1-Leg Squat | 31.82 ± 12.92 | 31.53 ± 13.98 | 0.55 | 9.01 | 20.96 | 24.97 | |

| Push-Up | 40.00 ± 24.12 | 43.48 ± 18.74 | 0.66 | 12.54 | 29.17 | 34.77 | |

| Shoulder Movements | 44.02 ± 26.35 | 40.22 ± 23.82 | 0.71 | 13.44 | 31.27 | 37.25 | |

| Trunk Movements | 22.83 ± 22.50 | 23.91 ± 27.67 | 0.80 | 11.28 | 26.24 | 31.26 | |

| Cervical Movements† | 59.78 ± 35.94 | 47.83 ± 29.11 | 0.84 | 12.91 | 30.03 | 35.79 | |

ME Test = Movement Efficiency Test; SD = standard deviation. ICC3,1 = two-way mixed effects model (3,1) intraclass correlation coefficient; SEM = standard error of measurement; MDC90% = minimal detectable change at the 90% confidence level; MDC95% = minimal detectable change at the 95% confidence level.

all are scored 0 – 100 (worst – best)

different at p < 0.05; results of repeated measures analyses of variance (RM ANOVAs).

The intra-rater test-retest reliability statistics of the binomial movement compensation data, and the associated interpretation of these statistics, are provided in Tables 2 – 8. In brief, the κPABA statistics suggest that the test-retest reliability of the individual movement compensations ranged from fair-to-almost perfect (κPABA range = 0.30 – 1.00), with an average observed agreement of 85.7% (range = 65% – 100%). Based on the guidelines of κPABA statistic interpretations previously suggested in the literature:19 22 out of 60 (37%) of the possible movement compensations have almost perfect reliability; 19 out of 60 (32%) of the possible movement compensations have substantial reliability; 14 out of 60 (23%) of the possible movement compensations have moderate reliability; 5 out of 60 (8%) of the possible movement compensations have fair reliability; and 0 out of 60 (0%) of the possible movement compensations have slight or poor reliability. Furthermore, these results suggest that 55 of the 60 (92%) individual movement compensations hold moderate-to-almost perfect intra-rater test-retest reliability, with 41 of the 60 (68%) individual movement compensations holding substantial-to-almost perfect intra-rater test-retest reliability.

Table 2.

Intra-rater test-retest agreement of movement compensations observed during 2-Leg Squat sub-test of the ME Test

| Compensation | Observed Agreement | κPABA | κPABA Interpretation* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right Foot Out | 70% | 0.39 | Fair |

| Left Foot Out | 70% | 0.39 | Fair |

| Right Foot Flattens | 83% | 0.65 | Substantial |

| Left Foot Flattens | 87% | 0.74 | Substantial |

| Right Knee Moves In | 96% | 0.91 | Almost Perfect |

| Left Knee Moves In | 91% | 0.83 | Almost Perfect |

| Right Knee Moves Out | 78% | 0.57 | Moderate |

| Left Knee Moves Out | 83% | 0.65 | Substantial |

| Excessive Forward Lean | 96% | 0.91 | Almost Perfect |

| Low Back Arches | 65% | 0.30 | Fair |

| Low Back Rounds | 100% | 1.00 | Almost Perfect |

| Arms Fall Forwards | 87% | 0.74 | Substantial |

| Right Heel of Foot Lifts | 100% | 1.00 | Almost Perfect |

| Left Heel of Foot Lifts | 100% | 1.00 | Almost Perfect |

| Right Asymmetrical Weight Shift | 87% | 0.74 | Substantial |

| Left Asymmetrical Weight Shift | 83% | 0.65 | Substantial |

ME Test = Movement Efficiency Test; κPABA = prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa statistic.

κPABA interpretation based on guidelines provided by Landis and Koch19

Table 8.

Intra-rater test-retest agreement of movement compensations observed during Cervical Movements sub-test of the ME Test

| Compensation | Observed Agreement | κPABA | κPABA Interpretation* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right Cervical Lateral Flexion: Compensation during movement / Unable to side-bend half the distance to the shoulder | 74% | 0.48 | Moderate |

| Left Cervical Lateral Flexion: Compensation during movement / Unable to side-bend half the distance to the shoulder | 83% | 0.65 | Substantial |

| Right Cervical Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to rotate chin to shoulder | 87% | 0.74 | Substantial |

| Left Cervical Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to rotate chin to shoulder | 70% | 0.39 | Fair |

ME Test = Movement Efficiency Test; κPABA = prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa statistic.

κPABA interpretation based on guidelines provided by Landis and Koch19

Table 3.

Intra-rater test-retest agreement of movement compensations observed during 2-Leg Squat with Heel Lift sub-test of the ME Test

| Compensation | Observed Agreement | κPABA | κPABA Interpretation* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right Foot Out | 87% | 0.74 | Substantial |

| Left Foot Out | 96% | 0.91 | Almost Perfect |

| Right Foot Flattens | 96% | 0.91 | Almost Perfect |

| Left Foot Flattens | 96% | 0.91 | Almost Perfect |

| Right Knee Moves In | 100% | 1.00 | Almost Perfect |

| Left Knee Moves In | 96% | 0.91 | Almost Perfect |

| Right Knee Moves Out | 91% | 0.83 | Almost Perfect |

| Left Knee Moves Out | 83% | 0.65 | Substantial |

| Excessive Forward Lean | 78% | 0.57 | Moderate |

| Low Back Arches | 74% | 0.48 | Moderate |

| Low Back Rounds | 100% | 1.00 | Almost Perfect |

| Arms Fall Forwards | 91% | 0.83 | Almost Perfect |

| Right Asymmetrical Weight Shift | 74% | 0.48 | Moderate |

| Left Asymmetrical Weight Shift | 83% | 0.65 | Substantial |

ME Test = Movement Efficiency Test; κPABA = prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa statistic.

κPABA interpretation based on guidelines provided by Landis and Koch19

Table 4.

Intra-rater test-retest agreement of movement compensations observed during 1-Leg Squat sub-test of the ME Test

| Compensation | Observed Agreement | κPABA | κPABA Interpretation* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right Leg – Foot Flattens | 78% | 0.57 | Moderate |

| Left Leg – Foot Flattens | 78% | 0.57 | Moderate |

| Right Leg – Knee Moves In | 87% | 0.74 | Substantial |

| Left Leg – Knee Moves In | 100% | 1.00 | Almost Perfect |

| Right Leg – Knee Moves Out | 100% | 1.00 | Almost Perfect |

| Left Leg – Knee Moves Out | 100% | 1.00 | Almost Perfect |

| Right Leg – Uncontrolled Trunk | 91% | 0.83 | Almost Perfect |

| Left Leg – Uncontrolled Trunk | 83% | 0.65 | Substantial |

| Right Leg – Loss of Balance | 83% | 0.65 | Substantial |

| Left Leg – Loss of Balance | 96% | 0.91 | Almost Perfect |

ME Test = Movement Efficiency Test; κPABA = prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa statistic.

κPABA interpretation based on guidelines provided by Landis and Koch19

Table 5.

Intra-rater test-retest agreement of movement compensations observed during Push-Up sub-test of the ME Test

| Compensation | Observed Agreement | κPABA | κPABA Interpretation* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head Moves Forward | 91% | 0.83 | Almost Perfect |

| Scapular Dyskinesis | 83% | 0.65 | Substantial |

| Low Back Arches / Stomach Protrudes | 87% | 0.74 | Substantial |

| Knees Bend | 70% | 0.39 | Fair |

ME Test = Movement Efficiency Test; κPABA = prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa statistic.

κPABA interpretation based on guidelines provided by Landis and Koch19

Table 6.

Intra-rater test-retest agreement of movement compensations observed during Shoulder Movements sub-test of the ME Test

| Compensation | Observed Agreement | κPABA | κPABA Interpretation* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right Shoulder – Flexion: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to wall | 74% | 0.48 | Moderate |

| Left Shoulder – Flexion: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to wall | 78% | 0.57 | Moderate |

| Right Shoulder – Internal Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to mid-line of trunk | 78% | 0.57 | Moderate |

| Left Shoulder – Internal Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to mid-line of trunk | 78% | 0.57 | Moderate |

| Right Shoulder – External Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to wall | 83% | 0.65 | Substantial |

| Left Shoulder – External Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to wall | 78% | 0.57 | Moderate |

| Right Shoulder – Horizontal Abduction: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to wall | 78% | 0.57 | Moderate |

| Left Shoulder – Horizontal Abduction: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to wall | 78% | 0.57 | Moderate |

ME Test = Movement Efficiency Test; κPABA = prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa statistic.

κPABA interpretation based on guidelines provided by Landis and Koch19

Table 7.

Intra-rater test-retest agreement of movement compensations observed during Trunk Movements sub-test of the ME Test.

| Compensation | Observed Agreement | κPABA | κPABA Interpretation* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right Trunk Lateral Flexion: Compensation during movement / Unable to touch lateral joint line of knee | 83% | 0.65 | Substantial |

| Left Trunk Lateral Flexion: Compensation during movement / Unable to tough lateral joint line of knee | 87% | 0.74 | Substantial |

| Right Trunk Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to rotate shoulder to midline | 96% | 0.91 | Almost Perfect |

| Left Trunk Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to rotate shoulder to midline | 91% | 0.82 | Almost Perfect |

ME Test = Movement Efficiency Test; κPABA = prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa statistic.

κPABA interpretation based on guidelines provided by Landis and Koch19

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the current study was to examine the intra-rater test-retest reliability and response stability of a relatively new functional movement assessment, known as the Fusionetics− ME Test. Results of this study suggest that the Overall ME Test score holds excellent intra-rater test-retest reliability and that the individual sub-tests hold fair-to-excellent intra-rater test-retest reliability (Table 1). These results imply that the ME Test holds adequate intra-rater test-retest reliability for use among practitioners and clinicians. In addition, the ICC associated with the Overall ME Test in the current study (ICC3,1 = 0.84) is similar to the intra-rater test-retest ICCs associated with the FMS− composite scores in the FMS− literature. Specifically, Bonazza et al.20 recently calculated a pooled ICC statistic of 0.81 across the FMS− literature.

Results of the current study also suggest that a change in Overall ME Test score of 12.68 points is required for this change in overall functional movement quality to be considered “real” (MDC95% = 12.68). This MDC value is associated with the error of the measure itself11,13 and is based upon the SEM calculated between the Day 1 and Day 2 ME Test scores (SEM = 4.57). Thus, a 12.68 increase in Overall ME Test score may represent a practically significant change in functional movement quality when the ME Test is being utilized among practitioners and clinicians to assess changes in the functional movement quality of an individual as a result of an intervention. Unlike the FMS−,6,7 the ME Test utilizes a 0 – 100 scoring scale for both the Overall ME Test score and each the sub-test score of the ME Test. As a result, even though previous research by Teyhen et al.21 has examined the MDC of the FMS−, it is not possible to compare the MDC95% of the ME Test identified in the current study to the MDC95% of the FMS (12.68 vs. 2.07, respectively).

However, since several recent studies have failed to identify improvements in FMS− scores as a result of targeted corrective or functional training programming,22–24 the clinical utility of the FMS− for use among practitioners and clinicians has been questioned.8,9 It has been previously suggested that a lack of responsiveness of the FMS− scoring system may be a result of the 0 – 3 ordinal scoring scale of the FMS− sub-tests may contribute to the equivocal clinical utility noted in the literature.25–29 Although a 0 – 100 scale has been introduced by developers of the FMS−,30,31 there is currently a lack of research utilizing this scoring scale. It is possible that the 0 – 100 scoring scale of the ME Test may prove to be more sensitive to changes in functional movement quality as a result of a targeted corrective exercise intervention, but further research to confirm this hypothesis is warranted.

In addition, the minimal clinically important difference (MCID), or the smallest change in which a patient/individual would consider to be beneficial,32 of the Overall ME Test score remains unidentified. Therefore, future research should explore the relationships between changes in ME Test scores as the result of an intervention with these individual's perceived benefits in functional movement quality.33 Such research would assist with determining the MCID associated with the ME Test and will help further elucidate the level of change in ME Test scores that are required to be clinically meaningful.

That said, systematic bias was potentially identified within the 2-Leg Squat with Heel Lift and Cervical Movements sub-tests, as significant differences ME Test scores were identified between Day 1 and Day 2, suggesting that systematic bias may be apparent within these specific sub-tests. It is possible that the differences between Day 1 and Day 2 are related to the number of movement compensations being assessed, differences in precise implementation of testing instructions for these sub-tests, and/or an expected amount of variability in movement quality across days. However, these potential mechanisms could only be considered speculative at this point and future research examining the potential variability in sub-tests scores across longer durations of time is required to further elucidate the potential, if any, influence of these factors. Furthermore, large ranges in the SEM and MDC statistics were identified within the individual sub-tests of the ME Test (Table 1). Taken together, these results indicate that the response stability varies among the individual sub-tests. Therefore, although the intra-rater test-retest reliability of the individual sub-tests ranged from fair-to-excellent, caution should be taken if utilizing a single sub-test of the ME Test to assess changes in functional movement quality and utilizing the Overall ME Test score may be more appropriate.

Similar to the results in the current study, previous research has also identified large, and sometimes conflicting, ranges in intra-rater test-retest reliability among the various FMS− sub-tests in the FMS− literature as well.34 Since it is possible that these ranges in FMS− sub-test reliability may be contributing to the questionable construct of the FMS− composite score,25–29 future research should also examine the factorial validity of the Overall ME Test score. Moreover, although both the ME Test and the FMS− quantify functional movement quality, the variance shared between these two assessments remains unexplored. Therefore, future research should also examine the criterion-reference validity of the ME Test in relation to the already established FMS− assessment.

Finally, since the Fusionetics− Human Performance System utilizes movement compensations identified during each sub-test to calculate each ME Test score, it is also important to examine the consistency associated with identifying these specific movement compensations. As such, the intra-rater test-retest reliability of the binomial movement compensation data of each individual sub-test of the ME Test was examined as well. The results of the current study suggest that the intra-rater test-retest reliability of the individual movement compensations ranged from fair-to-almost perfect. Although a large range in κPABA statistics were observed (κPABA range = 0.30 – 1.00), it should be noted that the vast majority (92%) of the individual movement compensations held moderate-to-almost perfect intra-rater test-retest reliability and an average observed agreement of 85.7% was found between the movement compensations identified on Day 1 and Day 2. These results suggest that the individual movement compensations associated with the scoring of each sub-test of the ME Test hold adequate intra-rater test-retest reliability as well. Collectively, these results provide further support for the response stability in the scoring of the Overall ME Test score, as consistency in the identification of these movement compensations would theoretically be required to create consistency in this scoring process.

Beyond the support regarding the reliability of the ME Test scoring methods, the current study introduces to the literature preliminary insight into the level of change in ME Test scores that is required to hold practical relevance. To date, this information is unknown and these results provide clinicians and practitioners with initial scientific evidence to guide the use of the ME Test as a functional outcome measure within their practice. Specifically, there is a growing trend among clinicians and practitioners to prescribe specific corrective exercises in an attempt to improve many of the same movement compensations observed during the ME Test.35,36 For example, the targeted strengthening of the gluteus medius and other proximal musculature in an effort to mitigate dynamic knee valgus observed during movement.37,38 Based on this growing trend and the results of the current study, improvements in ME Test scores may indicate successful mitigation of the observed movement compensations as a result of the targeted corrective exercise programming. Such outcomes would provide additional rationale for the sensitivity of the ME Test and support for its use as a useful assessment tool. However, further research examining both the responsiveness of the ME Test and the efficacy of such corrective exercise programming is required.

Limitations

There are limitations to consider with the current study. Similar to other commercially available products that rely on a proprietary algorithm to generate an outcome, the proprietary nature of the ME Test scoring does not allow for practitioners and researchers to identify how various movement compensations are weighted within the scoring calculations. Due to this, the reproducibility of this study is not generalizable without utilizing the Fusionetics− Human Performance System. The current study did, however, examine the intra-rater test-retest reliability of the 60 total movement compensations for each individual sub-test as well. Since the vast majority (92%) of the individual movement compensations held moderate-to-almost perfect intra-rater test-retest reliability, it is likely that the response stability of these scoring criteria resulted in the fair-to-excellent intra-rater test-retest reliability identified within the ME Test scores.

The results of the current study can also only be generalized to college-aged university students, as reliability must be established within each sample population of interest.10 Therefore, future research examining the intra-rater test-retest reliability and MDC characteristics should be conducted among other various clinical populations of interest (e.g., collegiate & professional athletes, tactical athletes, etc.). In addition, the current study utilized live assessment methods during each testing session, which meets the intended utility of the movement screen. It is possible that the assessment of movement compensations, and thus, the scoring of each sub-test, will differ between live and post hoc video analysis methods. Although use of video to make the assessments could become a practical limitation a movement screen for a clinician, future research should examine if differences in assessment methods exist within the scoring of the ME Test.

Finally, the researcher who performed all ME Test assessments in the current study (K.T.E.), was an ATC with greater than two years of previous experience with conducting the ME Test on numerous individuals. As a result, future research should be conducted to examine the intra-rater test-retest reliability of practitioners and clinicians of other professional backgrounds (e.g., strength and conditioning [S&C] professionals, physical therapists [PTs], etc.), as well as the effect of training and familiarity with the ME Test on the intra-rater test-retest reliability among various practitioners and clinicians. Similarly, although preliminary data has been presented regarding the inter-rater reliability of the ME Test,4,5 further research investigating the consistency in ME Test scoring between raters, and the potential scoring biases between raters of differing professional backgrounds (e.g., S&C professionals vs. PTs vs. ATCs, etc.), should be explored as well.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, results of the current study indicate that the Fusionetics− ME Test holds adequate intra-rater test-retest reliability for use among practitioners and clinicians. Results of the current study also suggest that a 12.68 point change in Overall ME Test score may represent a practically significant change in functional movement quality when utilizing the ME Test to assess changes in the functional movement quality of an individual as a result of an intervention. However, caution should be taken by practitioners and clinicians if deciding to utilize an individual sub-test of the ME Test to quantify and/or monitor changes in functional movement quality.

Appendix A.

Movement Efficiency (ME) Test Instructions Checklist

| Sub-Tests | Participant Positioning | Tester Instructions / Participant Actions |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Leg Squat |

|

|

| 2-Leg Squat with Heel Lift |

|

|

|

1-Leg Squat (completed bilaterally) |

|

|

| Push-Up |

|

|

| Shoulder Movements (4 total movements completed bilaterally) |

|

All of the above: Observe front & side views: perfonn one arm at a time |

| Trunk Movements (2 total movements completed bilaterally) |

|

All of the above: Observe front & side views: perform movement in each direction |

| Cervical Movements (2 total movements completed bilaterally) |

|

All of the above: Observe front & side views: perform movement in each direction |

Appendix B.

Movement Efficiency (ME) Test Grading Form

| 2-LEG SQUAT | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Checkpoint | Compensation | Right | Left |

| View: Front | |||

| Foot/Ankle | Foot Turns Out | ||

| Foot Flatterns | |||

| Knee | Knee Moves In (Valgus) | ||

| Knee Moves Out (Varus) | |||

| View: Side | |||

| L-P-H-C | Excessive Forward Lean | ||

| Low Back Arches Low Back Rounds | |||

| Low Back Arches Low Back Rounds | |||

| Shoulder | Arms Fall Forward | ||

| View: Back | |||

| Foot/Ankle | Heel of Foot Lifts | ||

| L-P-H-C | Asymmetrical Weight Shift | ||

| 2-LEG SQUAT WITH HEEL LIFT | |||

| Checkpoint | Compensation | Right | Left |

| View: Front | |||

| Foot/Ankle | Foot Turns Out | ||

| Foot Flattens | |||

| Knee | Knee Moves In (Valgus) | ||

| Knee Moves Out (Varus) | |||

| View: Side | |||

| L-P-H-C | Excessive Forward Lean | ||

| Low Back Arches | |||

| Low Back Rounds | |||

| Shoulder | Arms Fall Forward | ||

| View: Back | |||

| L-P-H-C | Asymmetrical Weight Shift | ||

| 1-LEG SQUAT | |||

| Checkpoint | Compensation | Right | Left |

| View: Front | |||

| Foot/Ankle | Foot Flattens | ||

| Knee | Knee Moves In (Valgus) | ||

| Knee Moves Out (Valgus) | |||

| L-P-H-C | Uncontrolled Trunk: Flexion, Rotation, and/or Hip Shift | ||

| Loss of Balance | |||

| PUSH-UP | |||

| Checkpoint | Compensation | Right | Left |

| View: Side | |||

| Spine | Head Moves Forward | ||

| Scapular Dyskinesis | |||

| L-P-H-C | Low Back Arches / Stomach Protrudes | ||

| Knees | Knees Bend | ||

| SHOULDER MOVEMENTS | |||

| Checkpoint | Compensation | Right | Left |

| View: Side | |||

| Shoulder | Flexion: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to wall | ||

| Internal Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to midline of trunk | |||

| External Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to wall | |||

| Horizontal Abduction: Compensation during movement / Unable to bring hand to wall | |||

| TRUNK MOVEMENTS | |||

| Checkpoint | Compensation | Right | Left |

| View: Front | |||

| Spine | Trunk Lateral Flexion: Compensation during movement / Unable to touch lateral joint line of knee with fingers | ||

| Trunk Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to rotate lateral aspect of shoulder to mid-line of sternum | |||

| CERVICAL MOVEMENTS | |||

| Checkpoint | Compensation | Right | Left |

| View: Front | |||

| Spine | Cervical Lateral Flexion: Compensation during movement / Unable to side-bend neck so that ear is approximately half the distance to shoulder | ||

| Cervical Rotation: Compensation during movement / Unable to rotate chin to acromion of shoulder | |||

L-P-H-C = Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip-Complex.

Note: if not specifically indicated, a compensation is defined as any accessory motion utilized by the individual that is not required to complete the desired movement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beardsley C Contreras B. The Functional Movement Screen: a review. Strength Cond J. 2014;36(5):72-80. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chimera NJ Warren M. Use of clinical movement screening tests to predict injury in sport. World J Orthop. 2016;7(4):202-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCunn R aus der Fünten K Fullagar HHK, et al. Reliability and association with injury of movement screens: a critical review. Sports Med. 2016;46(6):763-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornell DJ Ebersole KT. Inter-rater reliability of a movement efficiency test among the firefighter cadet population [abstract]. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(5 Suppl 1):97. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebersole KT Cornell DJ. Inter-rater response stability of a movement efficiency test among the firefighter cadet population [abstract]. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(5 Suppl 1):98.26258853 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook G Burton L Hoogenboom BJ, et al. Functional movement screening: the use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function – Part 1. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(3):396-409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook G Burton L Hoogenboom BJ, et al. Functional movement screening: the use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function – Part 2. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(4):549-563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minthorn LM Fayson SD Stobierski LM, et al. The Functional Movement Screen's ability to detect changes in movement patterns after a training intervention. J Sport Rehabil. 2015;24(3):322-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright AA Stern B Hegedus EJ, et al. Potential limitations of the Functional Movement Screen: a clinical commentary. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(13):770-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Portney LG Watkins MP. Reliability of measurements. In: Portney LG Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. 3rd ed Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2009:77-96. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19(1):231-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Portney LG Watkins MP. Statistical measures of reliability. In: Portney LG Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. 3rd ed Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2009:585-618. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portney LG Watkins MP. Statistical measures of validity. In: Portney LG Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. 3rd ed Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2009:619-658. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assessment. 1994;6(4):284-290. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cicchetti DV Feinstein AR. High agreement but low kappa: II. Resolving the paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(6):551-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feinstein AR Cicchetti DV. High agreement but low kappa: I. The problems of two paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(6):543-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byrt T Bishop J Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(5):423-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackinnon A. A spreadsheet for the calculation of comprehensive statistics for the assessment of diagnostic tests and inter-rater agreement. Comput Biol Med. 2000;30(3):127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landis JR Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonazza NA Smuin D Onks CA, et al. Reliability, validity, and injury predictive value of the Functional Movement Screen. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(3):725-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teyhen DS Shaffer SW Lorenson CL, et al. The Functional Movement Screen: a reliability study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(6):530-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beach TAC Frost DM McGill SM, et al. Physical fitness improvements and occupational low-back loading – an exercise intervention study with firefighters. Ergonomics. 2014;57(5):744-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frost DM Beach TAC Callaghan JP, et al. Using the Functional Movement Screen− to evaluate the effectiveness of training. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(6):1620-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pacheco MM Teixeira LA Franchini E, et al. Functional vs. strength training in adults: specific needs define the best intervention. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013;8(1):34-43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gnacinski SL Cornell DJ Meyer BB, et al. Functional Movement Screen factorial validity and measurement invariance across sex among collegiate student-athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(12):3388-3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazman JB Galecki JM Lisman P, et al. Factor structure of the Functional Movement Screen in Marine officer candidates. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(3):672-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koehle MS Saffer BY Sinnen NM, et al. Factor structure and internal validity of the Functional Movement Screen in adults. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(2):540-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraus K Schütz E Taylor WR, et al. Efficacy of the Functional Movement Screen: a review. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(12):3571-3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y Wang X Chen X, et al. Exploratory factor analysis of the Functional Movement Screen in elite athletes. J Sports Sci. 2015;33(11):1166-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butler RJ Plisky PJ Kiesel KB. Interrater reliability of videotaped performance on the Functional Movement Screen using the 100-point scoring scale. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2012;4(3):103-109. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hickey JN Barrett BA Butler RJ, et al. Reliability of the Functional Movement Screen using a 100-point grading scale [abstract]. Med Sci Sports Sci. 2010;42(5 Suppl 1):392. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaeschke JR Singer J Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10(4):407-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Revicki D Hays RD Cella D, et al. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(2):102-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moran RW Schneiders AG Major KM, et al. How reliable are Functional Movement Screening scoresϿ. A systematic review of rater reliability. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(9):527-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark MA, Lucett SC. Movement assessments. In: Clark MA Lucett SC. NASM Essentials of Corrective Exercise Training. 1st ed Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011:105-141. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirth CJ. Clinical movement analysis to identify muscle imbalances and guide exercise. Athl Ther Today. 2007;12(4):10-14. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Powers CM. The influence of abnormal hip mechanics on knee injury: a biomechanical perspective. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(2):42-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Presswood L, Cronin J, Keogh JW, et al. Gluteus medius: applied anatomy, dysfunction, assessment, and progressive strengthening. Strength Cond J. 2008;30(5):41-53. [Google Scholar]